1. Introduction

Dopamine, a critical neuromodulator, plays essential roles in regulating movement, motivation, and memory across species[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In humans, disruptions in dopaminergic neuron (DN) functionality are central to the pathophysiology of disorders such as Schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease

2. In Parkinson’s, DNs degenerate in the substantia nigra, leading to the classic motor symptoms of the disease, such as tremors, muscle stiffness, and bradykinesia[

1]. Conversely, Schizophrenia is often associated with hyperactive dopamine transmission, leading to its characteristic symptoms[

4]. Notably, sleep disturbances emerge as a common thread across these conditions, underscoring the intricate relationship between dopamine signaling and sleep regulation.

The influence of dopamine on the sleep-wake cycle has been extensively documented across various animal models. In mammals, sleep encompasses two primary states: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, marked by decreased sensory responsiveness and consciousness, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, characterized by muscle atonia, eye movement, and vivid dreaming[

6]. Dopaminergic activity is known to spike in anticipation of REM sleep, with studies indicating that enhanced dopamine levels are crucial for initiating this phase. Dzirasa et al. showed that both genetically and pharmacologically induced hyperdopaminergic mice display hippocampal neural oscillations similar to those found in REM sleep[

7]. Furthermore, Lima et al. demonstrated that rats treated with MPTP, a neurotoxin that targets dopaminergic neurons, exhibit a significant increase in REM sleep latency and decrease in REM sleep time compared to control rats, highlighting dopamine’s pivotal role in sleep architecture[

8].

Additionally, dopamine’s role extends to arousal, with certain genetic and pharmacological manipulations demonstrating altered sleep patterns and responsiveness to stimulants. A study done by Wisor et al. showed that dopamine transporter knockout mice were found to be unresponsive to the normally wake-promoting effect of stimulants such as methamphetamine and modafinil[

9]. Another study done by Kropf and Kuschinsky demonstrated that rats treated with a dopamine receptor agonist exhibited a significant increase in wakefulness[

10].

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, has emerged as a valuable model for sleep-wake cycle research, offering insights into sleep defined by prolonged inactivity periods and increased arousal thresholds[

11,

12]. The relatively simple and genetically accessible nervous system of Drosophila enables detailed study of sleep regulation mechanisms.

The emergence of optogenetics, a technique enabling precise control over neuronal activity via light-sensitive ion channels, has transformed the study of neural mechanisms underlying sleep regulation[

13]. By employing optogenetics to activate or silence dopaminergic neurons (DNs) in Drosophila, researchers can directly examine consequent changes in sleep and wakefulness. Utilizing the

GAL4/UAS system facilitates targeted neuronal manipulation[

14]. The present study aims to elucidate the role of dopaminergic neurons in regulating sleep in fruit flies. Through optogenetic modulation of DN activity, we evaluated subsequent changes in sleep patterns and general activity. This methodological approach provides new insights into the neural control of sleep and may contribute to understanding sleep disturbances characteristic of dopamine-related disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drosophila Strains and Fly Husbandry

We utilized in-house Drosophila melanogaster strains for our experiments, maintained under controlled conditions to ensure consistency and reliability. These flies were kept in an incubator programmed to regulate environmental conditions conducive to fly health and consistent sleep/wake rhythmicity. Settings were programmed with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a temperature of 22°C, housed in vials containing conventional cornmeal agar medium to provide nutrition (Gennesse) and support their lifecycle.

2.2. Activity Assay

To investigate the role of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in sleep-wake regulation, we conducted activity assays using in-house

GAL4 and

UAS fly stocks. These lines were independently validated over five consecutive years to confirm their red- and yellow-light permeability and to characterize the neuronal activation or inactivation they elicit—particularly for escape responses. This verification ensured their suitability for sophisticated sleep-wake analyses using our DAM system and established protocols[

15].

Fly Crosses and Rearing: Parental flies were anesthetized under CO₂ and sorted by sex and balancer chromosome (

w =

DA-GAL4;

Sb = Halo). Virgin females (F0) expressing

GAL4-DA on chromosome 3 were crossed with males carrying a YFP-tagged, yellow-light-activated

halorhodopsin-UAS chloride channel on chromosome 2. For photo-activation experiments targeting the same subset of CC-DN neurons, Venus-tagged, red-shifted

channelrhodopsin-UAS males (

w, chromosome 2) were crossed with

DA-GAL4 (

w, chromosome 3) virgin females[

16]. All crosses were maintained in food vials supplemented with 100 mM all-trans retinal dissolved in ethanol and incubated until pupal emergence (approximately three weeks).

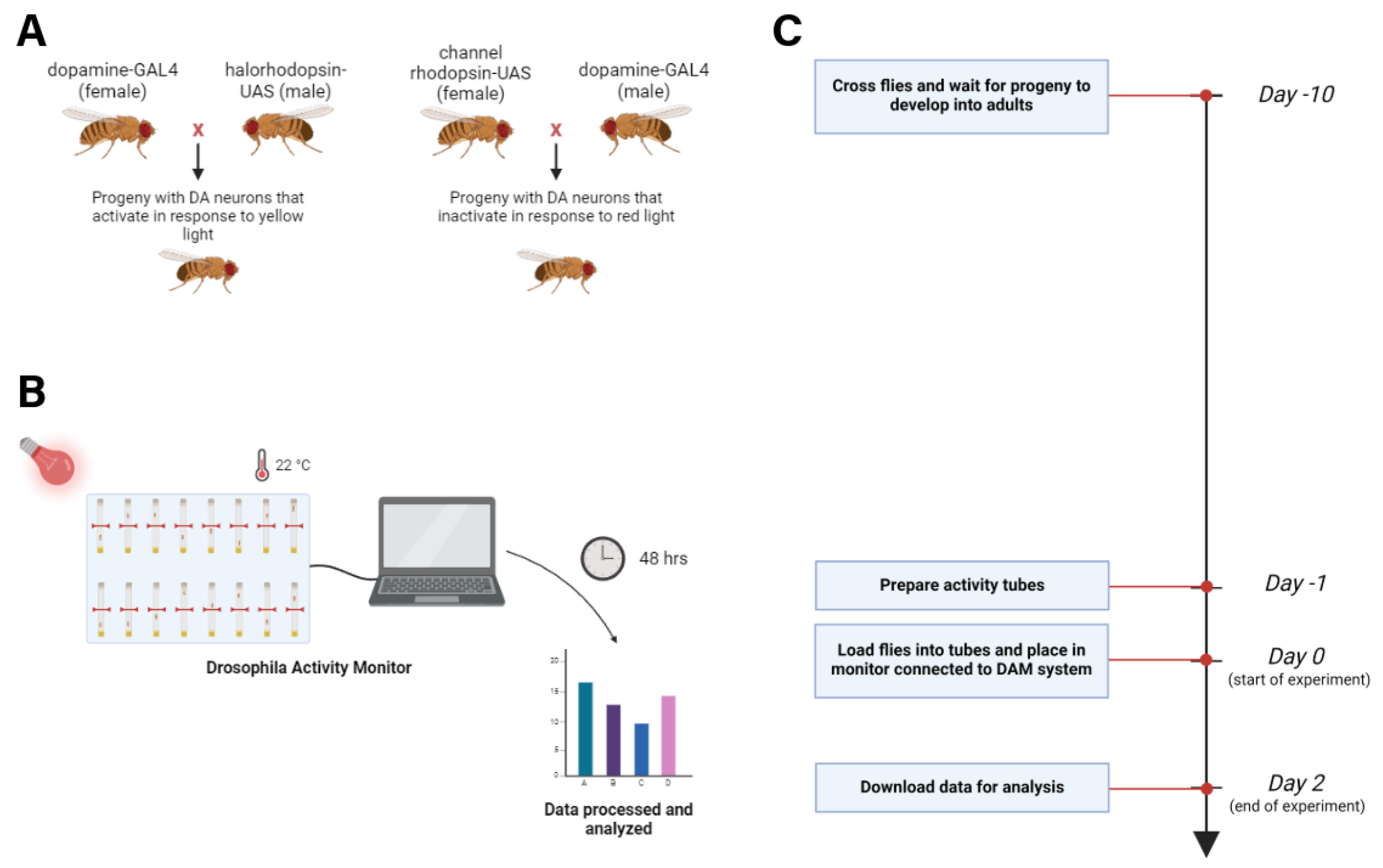

DAM Sleep-Wake Assay: The overall genetic scheme and the DAM-based sleep-wake, light-dark behavioral protocol are depicted in

Figure 1A. Healthy F1 male offspring (1–5 days post-eclosion) were anesthetized under CO₂ and placed individually into glass capillary vials containing retinal-supplemented food at both ends (Fig. 1B–1C). These vials were then loaded into a Drosophila Activity Monitor (DAM) system, which recorded locomotor activity continuously over a 48-hour period under a 12:12 light-dark cycle.

For subsequent experimental manipulation, DAM trays were transferred to a large temperature-controlled room free of external stimuli or staff use. The inactivation group (expressing halorhodopsin) was exposed to continuous yellow light (580 nm LED flashlights, 200 lumens), while the activation group (expressing channelrhodopsin) was exposed to continuous red light (620 nm tactical CREE XP-E LED flashlights, 200 lumens). Sleep and wakefulness patterns were then analyzed to determine the impact of DA neuron modulation.

Parental flies were anesthetized under CO₂ and sorted based on sex and balancer chromosome presence (w = DA-GAL4; Sb = Halo). Virgin adult females (F0) expressing GAL4-DA on chromosome 3 were crossed with males carryinh a YFP-tagged, yellow-light-activated halorhodopsin-UAS chloride channel construct on chromosome 2.

Crosses were maintained in food vials containing 100 mM all-trans retinal dissolved in ethanol[

16] and returned to their original incubator environment for approximately three weeks until pupae emerged.

For complementary photo-activation experiments targeting the same subset of CC-DN neurons during a 48-hour sleep/wake cycle, adult males carrying a Venus-tagged, red-shifted, light-activated channelrhodopsin-UAS construct (w, chromosome 2) were crossed with DA-GAL4 (w, chromosome 3) virgin females. These vials also contained the same concentration of all-trans retinal.

The genetic crossing paradigm and the experimental DAM sleep-wake, light-dark behavioral assay protocol are visually depicted in

Figure 1A. For experimental assays, healthy male offspring aged 1–5 days were isolated under CO₂ anesthesia and placed into glass capillary vials containing all-trans-retinal food at both ends. These vials were then inserted into a Drosophila Activity Monitor, which enabled tracking of fly movements. Activity data were recorded continuously over a 48-hour period under a consistent 12-hour light/dark schedule to evaluate how DA neuron modulation affected sleep and wakefulness patterns (Fig. 1B–1C). DAM trays were subsequently transferred to a larger, temperature-controlled room for experimental testing. The inactivation group was exposed to continuous yellow light (580 nm LED flashlights, 200 lumens), while the activation group was exposed to continuous red light (620 nm tactical CREE XP-E LED flashlights, 200 lumens).

2.3. Data Analysis

Raw activity data from the Drosophila Activity Monitors were initially processed using DAMFileScan software, an integral component of the TriKinetics DAM System. Further analyses were performed using the SCAMP program in MATLAB, following established methodologies[

11,

17] to comprehensively evaluate sleep and activity metrics. Results were graphically represented using Prism software, with supplementary image processing conducted via ImageJ. Each experiment was replicated at least twice to confirm consistency and reproducibility. Statistical significance between experimental and control conditions was assessed using Student’s t-test, ensuring rigorous statistical analyses androbust, accurate interpretation of findings.

3. Results

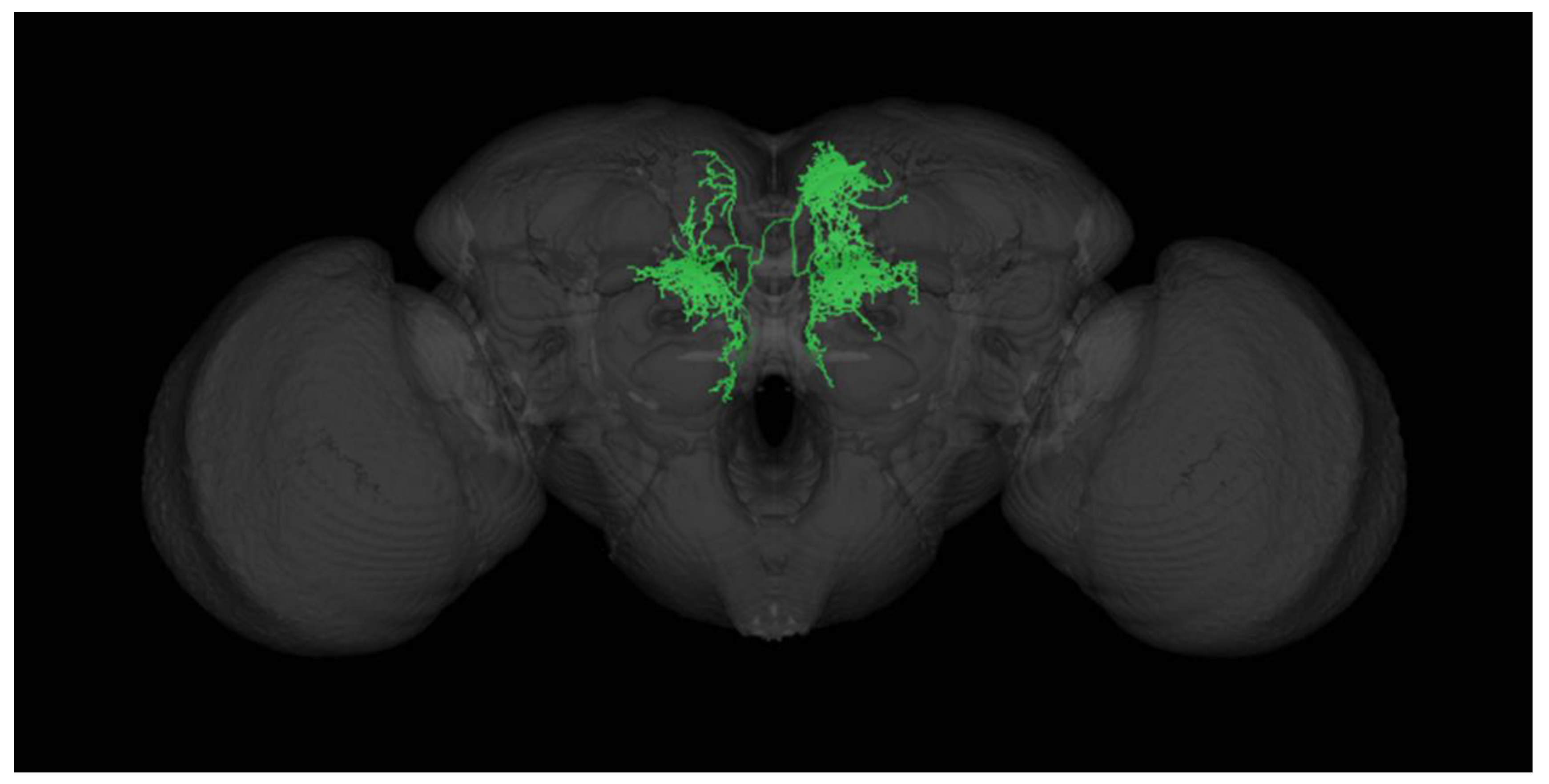

Our study focused on examining the consequences of acute CC-DN modulation on sleep and activity patterns in adult (1–5-day-old) Drosophila melanogaster over a 48-hour period, under a consistent 12-hour light/dark cycle. We evaluated the effects of chronic activation and inactivation of dopaminergic neurons (DNs). Activation was induced in channelrhodopsin-expressing flies via exposure to red light, while inactivation was achieved in halorhodopsin-expressing flies through exposure to continuous yellow light throughout the experiment. A diagram of the CC-DNs targeted in this investigation is depicted in

Figure 2.

3.1. Effect of DN Modulation on Circadian Rhythms

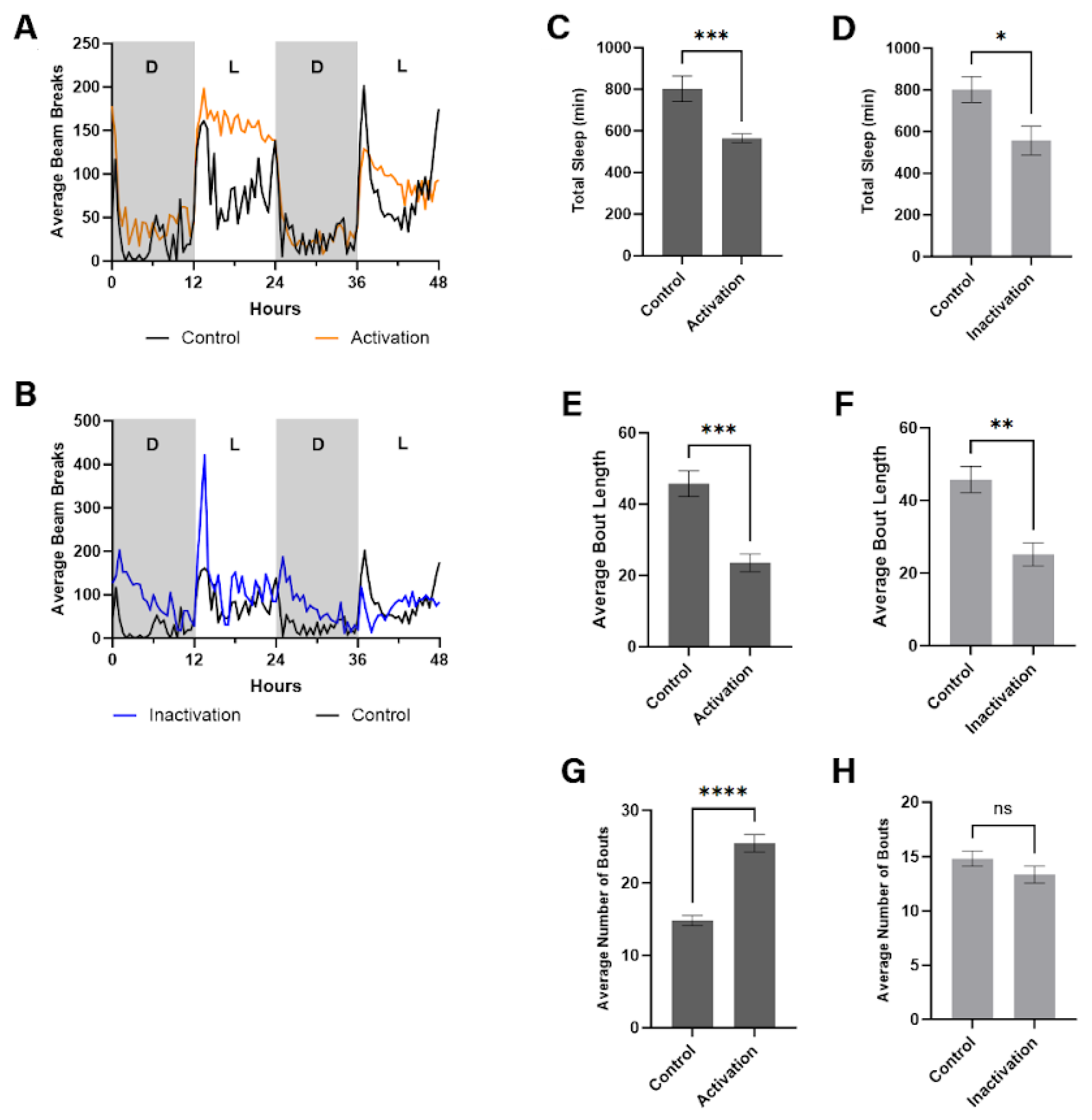

Our analyses revealed significant alterations in circadian rhythms in flies subjected to DN modulation. Specifically, flies with chronically activated DNs demonstrated increased activity levels during the light phase of the cycle, as illustrated in

Figure 3A. This enhancement of daytime activity indicates a shift in the flies' sleep-wake cycle, primarily marked by diminished sleep or rest periods during what typically constitutes their active phase. Conversely, no significant deviation in activity levels from controls was observed during the dark phase, suggesting that DN activation predominantly influences behavior during the light (daytime) period.

In contrast, flies with chronically inactivated DNs demonstrated an initial surge in activity at the onset of the dark cycle, diverging from the patterns observed in control flies (Fig. 3B). This increase suggests an alteration in their readiness to transition into the rest phase, possibly indicating a delayed sleep onset or a disruption in the initiation of sleep-related processes. However, during the light phase, these flies did not exhibit any notable change in activity compared to the controls, highlighting that DN inactivation specifically impacts behavior associated with the transition into the dark cycle.

These findings underscore the complex role of dopaminergic neurons in regulating circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles in fruit flies. The differential effects observed with DN activation and inactivation provide insight into the neuronal mechanisms underlying circadian behavior, suggesting that dopamine signaling is crucial for maintaining the balance between activity and rest phases in these organisms. Further analyses and studies are warranted to reveal the underlying molecular and neural circuitry mechanisms facilitating these observed behaviors.

3.2. The Effect of DN Modulation on Sleep

Sleep is a critical physiological state that supports essential processes such as memory consolidation, metabolic regulation, and neuronal restoration. Although the importance of DNs in circadian timing is well-established, their direct influence on sleep quantity and architecture has received less attention. Because DNs help drive rhythmic behavioral outputs, it is plausible that these same neurons also contribute to regulating total sleep time and sleep fragmentation. By systematically manipulating DN activity, we aimed to elucidate how these neurons integrate circadian cues with sleep homeostatic mechanisms, thereby enhancing our understanding of both the neural circuitry underlying sleep in Drosophila and potential parallels in other organisms.

In addition to exploring the impact of DN modulation on circadian rhythms, our study investigated how such modulation affects total sleep time in Drosophila melanogaster. Utilizing our validated activity assay setup over a 48-hour period under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, we quantitatively assessed sleep patterns following chronic activation or inactivation of DNs. Our findings revealed that chronic activation of DNs led to a substantial reduction in total sleep duration, as seen in

Figure 3C. Specifically, flies subjected to continuous activation (via channelrhodopsin-gated NA++ channel opening under red light exposure) exhibited a significant decrease in total sleep, with a

p-value less than 0.001 when compared to control flies (age-, sex-,

UAS-ChR carrying). This pronounced reduction underscores the role of activated dopaminergic signaling in diminishing sleep quantity, potentially mimicking wakefulness-promoting effects observed in other models.

Similarly, chronic inactivation of DNs (achieved through halorhodopsin and yellow light exposure) also resulted in a notable decrease in total sleep, albeit to a lesser extent than with DN activation (

Figure 3D). The decrease in sleep duration among these flies was statistically significant, with a p-value less than 0.05 in comparison to control groups (detailed above). This suggests that while dopaminergic inactivation disrupts normal sleep patterns, its effect on reducing sleep quantity is less pronounced than that of dopaminergic activation.

These observations indicate a critical role for dopaminergic neurons in regulating sleep in fruit flies, with both the enhancement and suppression of dopaminergic activity leading to decreased sleep duration. The differential impact of DN activation versus inactivation on sleep quantity highlights the complex and nuanced nature of dopamine's involvement in sleep regulation, suggesting that dopaminergic signaling pathways are integral to the maintenance of normal sleep architecture. Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the precise mechanisms through which dopaminergic modulation influences sleep and to explore the potential therapeutic implications for sleep disorders associated with dopaminergic dysfunction.

3.3. The Effect of DN Modulation on Number of Sleep Bouts

Our investigation into the role of DN modulation on sleep architecture extended to analyzing the number of sleep bouts in Drosophila melanogaster. This metric provides insight into the fragmentation of sleep, an important aspect of sleep quality and regulation. By assessing sleep bout frequency over a 48-hour period under a consistent 12-hour light/dark cycle, we determined the effects of chronic DN activation and inactivation.

In flies with chronically activated DNs, there was a marked increase in the mean number of sleep bouts compared to control flies. Statistical analysis revealed a robust significant difference (p < 0.0001), indicating that continuous activation of dopaminergic neurons leads to more fragmented sleep (

Figure 3E). This fragmentation, characterized by an increased number of sleep interruptions, suggests that dopaminergic activation disrupts the continuity of sleep, resulting in shorter, more frequent periods of rest.

Conversely, flies with chronically inactivated DNs showed no significant difference in the mean number of sleep bouts compared to control flies (p > 0.05), as depicted in

Figure 3F. This outcome suggests that dopaminergic inactivation does not significantly affect sleep fragmentation in the same way activation does. The absence of a significant effect on sleep bout frequency implies that while inactivation may alter total sleep duration, it does not lead to increased sleep fragmentation as observed with dopaminergic activation.

These findings highlight a distinct role of dopaminergic signaling in modulating sleep continuity in fruit flies. The increase in sleep bout number with DN activation points to a potential mechanism through which dopamine influences sleep architecture, contributing to sleep disruption by increasing wakefulness or causing sleep fragmentation. This contrast with the effects of DN inactivation underscores the complexity of dopamine's role in circadian rythms, emphasizing the need for further research to understand the underlying neural and molecular mechanisms utilizing genetically tractable model organisms, like flies.

3.4. The Effect of DN Modulation on Average Bout Length

Continuing our examination of how DN modulation influences sleep architecture in Drosophila melanogaster, we also assessed the average length of sleep bouts. This measure provides insight into the duration of continuous sleep segments, offering another perspective on sleep quality and its regulation by dopaminergic activity.

In flies subjected to chronic DN activation, we observed a significant reduction in the mean length of sleep bouts compared to the control group (

Figure 3G). Statistical analysis yielded a

p-value less than 0.001, indicating that activating dopaminergic neurons leads to significantly shorter sleep segments. This result suggests that dopaminergic activation not only increases sleep fragmentation but also significantly decreases the duration of individual sleep bouts, contributing to a more disrupted sleep pattern.

Similarly, chronic DN inactivation also resulted in a notable decrease in the average bout length, although the effect was somewhat less pronounced than with DN activation (

Figure 3H). The decrease observed in flies with dopaminergic inactivation was significant, with a

p-value less than 0.01 when compared to controls. This indicates that inactivation of dopaminergic neurons also affects sleep continuity, leading to shorter periods of uninterrupted sleep, albeit to a lesser extent than observed with activation.

These findings underscore the complex role of dopaminergic signaling in sleep regulation. Both the activation and inactivation of DNs have significant impacts on the continuity of sleep, as reflected in the reduced length of sleep bouts. This disruption in sleep bout duration provides further evidence of the critical role that dopaminergic pathways play in maintaining neurotypical sleep patterns. The observed alterations in sleep architecture, with both enhanced and suppressed dopaminergic activity leading to shorter sleep bouts, highlight the nuanced and bidirectional influence of dopamine on sleep. Further investigations will be essential to elucidate the mechanisms through which dopaminergic modulation exerts these effects on sleep architecture and to explore implications for treating sleep disorders associated with dopaminergic dysregulation.

4. Discussion

Our exploration of chronic dopaminergic neuron (DN) modulation in Drosophila melanogaster reveals promising evidence of dopamine’s critical role in sleep regulation. We found that both chronic DN activation and inactivation significantly affect sleep and activity, corroborating and expanding upon recent literature reporting similar neuromodulatory influences of DA neuronal transmission affecting sleep.

Contrary to our initial hypotheses, both chronic DN activation and inactivation led to significant reductions in total sleep duration (

Figure 3A–1B). This was especially surprising for the inactivation group, given dopamine’s well-established role in promoting arousal[

18,

19]. These findings indicate that dopamine’s influence on sleep extends beyond simple arousal control and that either excessive or insufficient dopaminergic signaling disrupts normal sleep architecture. This dual effect underscores the importance of maintaining dopamine homeostasis for healthy sleep patterns.

Our results parallel those in human conditions characterized by dopaminergic dysfunction, notably Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia, both of which frequently involve insomnia or other sleep disturbances[

1,

4,

20]. This resemblance suggests that the sleep disruptions observed in our

Drosophila model may reflect fundamental dopaminergic processes in sleep regulation, offering a valuable comparative framework for understanding dopaminergic contributions to sleep disorders.

The study also highlights DN modulation’s influence on sleep fragmentation. Chronic DN activation significantly increased the number of sleep bouts and reduced their duration, suggesting greater fragmentation (

Figure 3E, 3G). This aligns with previous research showing that dopaminergic stimulation can interrupt sleep continuity, thereby promoting wakefulness[

9,

18]. In contrast, chronic DN inactivation decreased sleep bout length without altering the number of bouts (

Figure 3F, 3H), underscoring the nuanced ways in which dopaminergic signaling shapes sleep architecture. These distinct effects of activation versus inactivation emphasize the delicate balance required for optimal sleep quality.

The consistent shortening of sleep bout length under both DN activation and inactivation raises provocative questions regarding underlying mechanisms. These findings suggest that maintaining continuous, restorative sleep depends not just on the presence of dopamine but also on the precise regulation of it’s signaling pathways. Disruption of this balance—through either overstimulation or blockade—leads to fragmented, lower-quality sleep, underscoring the complexity of dopaminergic function in sleep regulation.

In conclusion, our work underscores the pivotal role dopaminergic neurons play in governing sleep dynamics, emphasizing the necessity of balanced dopaminergic signaling for normal sleep patterns. The parallels between our Drosophila model and human conditions marked by dopaminergic dysfunction reinforce the model’s utility in dissecting sleep disturbances linked to diseases like Parkinson’s and schizophrenia. Future research should further unravel the molecular mechanisms by which dopaminergic modulation influences sleep architecture and explore potential therapeutic interventions to mitigate sleep disturbances in dopaminergic-related disorders.

4. Discussion

Our investigation into the chronic modulation of dopaminergic neurons (DNs) in Drosophila melanogaster uncovers compelling evidence for dopamine’s pivotal role in sleep regulation. Both chronic DN activation and inactivation significantly altered sleep and activity, aligning with and extending recent work that highlights dopamine’s neuromodulatory influence on sleep.

Contrary to our initial hypotheses, both chronic DN activation and inactivation reduced total sleep duration (

Figure 3A–1B)—a particularly striking result for the inactivation group, given dopamine’s established role in arousal control[

18,

19]. These findings suggest that dopamine’s impact on sleep transcends simple arousal promotion and that either excessive or insufficient dopaminergic signaling disrupts normal sleep architecture. Maintaining dopaminergic homeostasis thus appears vital for preserving healthy sleep.

Our results resonate with observations in human conditions characterized by dopaminergic dysfunction, such as Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia, where insomnia or related sleep disturbances are common[

1,

4,

20]. This parallel implies that our Drosophila model recapitulates fundamental dopaminergic processes underlying sleep, offering a powerful platform for probing dopaminergic contributions to sleep disorders.

We also demonstrate that DN modulation influences sleep fragmentation. Chronic DN activation increased the number of sleep bouts while shortening their duration (

Figure 3E,

Figure 3G), corroborating earlier reports that dopaminergic stimulation can interrupt sleep continuity and promote wakefulness[

9,

18]. Conversely, DN inactivation decreased sleep bout length without changing the number of bouts (

Figure 3F,

Figure 3H), underscoring the nuanced ways in which dopaminergic signaling orchestrates sleep structure. These opposing patterns highlight the delicate equilibrium required for maintaining high-quality sleep.

The consistent reduction in bout length across both DN activation and inactivation raises questions about underlying mechanisms. Continuous, restorative sleep hinges not merely on the presence of dopamine but also on finely tuned dopaminergic pathways. Perturbing this balance—through overstimulation or blockade—produces fragmented, lower-quality sleep, underscoring dopamine’s complex role in regulating sleep.

In conclusion, our work underscores the central function of dopaminergic neurons in governing sleep dynamics, emphasizing the necessity of balanced dopaminergic signaling for normal sleep architecture. The parallels between our Drosophila model and human disorders involving dopaminergic dysfunction reinforce this model’s utility in dissecting sleep disturbances tied to diseases such as Parkinson’s and schizophrenia. Future research should delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms of dopaminergic control oversleep and investigate potential therapeutic strategies to alleviate sleep disorders rooted in dopaminergic dysregulation.

Author Contributions

M.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing, and original draft preparation. K.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, review, editing, and supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in study available on author’s Github account, which can be found here.

Inclusion and Diversity Statement

At least one contributor to this manuscript identifies as belonging to groups historically underrepresented in academia, including ethnic minorities, gender-diverse individuals, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, or persons living with disabilities. The authors consciously strived for equitable gender representation within the reference section and carefully integrated relevant and diverse scholarly sources.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carlsson, A. Perspectives on the Discovery of Central Monoaminergic Neurotransmission. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 19–40 (1987).

- Beitz, J. M. Parkinson s disease a review. Front Biosci S6, 65–74 (2014).

- Beninger, R. J. The role of dopamine in locomotor activity and learning. Brain Research Reviews 6, 173–196 (1983).

- Brisch, R.; et al. The Role of Dopamine in Schizophrenia from a Neurobiological and Evolutionary Perspective: Old Fashioned, but Still in Vogue. Front. Psychiatry 5, (2014).

- Goldman-Rakic, P. S. The Cortical Dopamine System: Role in Memory and Cognition. in Advances in Pharmacology vol. 42 707–711 (Elsevier, 1997).

- Court, R.; et al. Virtual Fly Brain—An interactive atlas of the Drosophila nervous system. Front. Physiol. 14, 1076533 (2023).

- Scammell, T. E., Arrigoni, E. & Lipton, J. O. Neural Circuitry of Wakefulness and Sleep. Neuron 93, 747–765 (2017).

- Lima, M. M. S., Andersen, M. L., Reksidler, A. B., Vital, M. A. B. F. & Tufik, S. The Role of the Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta in Regulating Sleep Patterns in Rats. PLoS ONE 2, e513 (2007).

- Wisor, J. P.; et al. Dopaminergic Role in Stimulant-Induced Wakefulness. J. Neurosci. 21, 1787–1794 (2001).

- Kropf, W. & Kuschinsky, K. Effects of stimulation of dopamine D1 receptors on the cortical EEG in rats: Different influences by a blockade of D2 receptors and by an activation of putative dopamine autoreceptors. Neuropharmacology 32, 493–500 (1993).

- Driscoll, M., Hyland, C. & Sitaraman, D. Measurement of Sleep and Arousal in Drosophila. BIO-PROTOCOL 9, (2019).

- Hendricks, J. C.; et al. Rest in Drosophila Is a Sleep-like State. Neuron 25, 129–138 (2000).

- Packer, A. M., Roska, B. & Häusser, M. Targeting neurons and photons for optogenetics. Nat Neurosci 16, 805–815 (2013).

- Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415 (1993).

- Dugan, C., Quidore, L., Gobrogge, K.L., & Tullai, J. Automating behavior analysis in Drosophila melanogaster in a large undergraduate neuroscience laboratory course. in Advances in Biology Laboratory Education, A Publication of the Association for Biology Laboratory vol. 44 21 (Association for Biology Laboratory Education, University of California - San Diego, 2024).

- Vilinsky, I., Hibbard, K. L., Johnson, B. R. & Deitcher, D. L. Probing Synaptic Transmission and Behavior in Drosophila with Optogenetics: A Laboratory Exercise. J Undergrad Neurosci Educ 16, A289–A295 (2018).

- Donelson, N.; et al. High-Resolution Positional Tracking for Long-Term Analysis of Drosophila Sleep and Locomotion Using the “Tracker” Program. PLoS ONE 7, e37250 (2012).

- Dzirasa, K.; et al. Dopaminergic Control of Sleep–Wake States. J. Neurosci. 26, 10577–10589 (2006).

- Shaw, P. J., Cirelli, C., Greenspan, R. J. & Tononi, G. Correlates of Sleep and Waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287, 1834–1837 (2000).

- Cools, R. Role of Dopamine in the Motivational and Cognitive Control of Behavior. Neuroscientist 14, 381–395 (2008).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).