1. Introduction

Extensive research has been conducted on the phytoremediation capacities of various aquatic and terrestrial plant species. This method is considered environmentally friendly and aligns with natural ecological processes, unlike some conventional remediation techniques that may disrupt soil structure or ecological balance through excavation or the use of aggressive chemicals and energy-intensive processes [

7,

18,

41,

88]. Phytoremediation requires minimal external inputs such as energy and synthetic chemicals, making it a low-cost and sustainable alternative, especially for large-scale or long-term applications. Moreover, phytoremediation demonstrates multiple co-benefits for environmental protection [

45,

48]. In addition to removing pollutants such as heavy metals, arsenic, and organic contaminants from soil and water [

39,

71], it helps prevent the leaching of contaminants into groundwater sources [

82]. This serves a crucial function in safeguarding drinking water supplies and maintaining aquifer health. Certain plant species also contribute to air purification by absorbing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and reducing dust and particulate matter, thereby improving local air quality [

89].

Equally important, phytoremediation enhances the surrounding landscape by restoring vegetation cover, which can rehabilitate degraded lands and improve biodiversity [

15,

41]. The establishment of diverse plant communities through phytoremediation contributes to the restoration of ecological functions and supports a variety of species, thereby increasing biodiversity [

47]. The presence of green vegetation contributes to aesthetic improvement and promotes ecosystem services, such as erosion control, microclimate regulation, and carbon sequestration. For instance, vegetation cover can stabilize soil, reducing erosion [

110], and influence local microclimates by providing shade and transpiration cooling [

84]. Additionally, plants involved in phytoremediation can sequester carbon in their biomass and the soil, contributing to climate change mitigation efforts [

47]. These features make phytoremediation not only a practical remediation tool but also a catalyst for sustainable land and water management practices.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of phytoremediation in removing a range of inorganic pollutants, such as heavy metals [

8,

21,

69,

110], as well as organic contaminants. For instance, phytoremediation has been successfully applied to remove heavy metals like lead, cadmium, and arsenic from contaminated soils and water bodies. Additionally, this green technology has shown efficacy in degrading organic pollutants, including BTEX compounds (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) [

19,

43], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [

57], chlorinated solvents [

31]such as trichloroethylene [

27], and various pesticides [

23,

33,

95,

97]. Emerging contaminants, including pharmaceuticals and personal care products, have also been targeted using phytoremediation strategies, highlighting the versatility and potential of this approach in addressing diverse environmental pollutants [

57,

61].

Today, as environmental pollutants are increasingly detected in various environmental compartments [

49,

65,

72,

98,

99], phytoremediation has become a suitable solution because it avoids the need for multiple costly treatment steps. Phytoremediation utilizes various plant species to remove, stabilize, or degrade environmental pollutants, with the selection of specific plants depending on the type of contaminant and the site conditions. Different types of contaminants that cause harmful effects on human health and other biological systems can be removed by appropriate plant species. These plants absorb pollutants from the environment and detoxify their toxic effects.

Table 1.

Overview of selected plant species used for the removal of specific pollutants in water.

Table 1.

Overview of selected plant species used for the removal of specific pollutants in water.

| Plant |

Type |

Contaminant |

Ref. |

| S. molesta |

Dye |

Tartrazine and Bordeaux red |

[35] |

| Azolla pinnata |

Dye |

Methylene blue |

[6] |

| Aster amellus, Glandularia pulchella, Zinnia angustifolia |

Dye |

Acid Orange 7 and Sulfonated anthraquinones |

[59] |

| Eichhornia crassipes |

Dye |

Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange

Rose bengal, Methylene blue, Crystal violet, Auramine O, Rhodamine B, Xylenol orange, Phenol red, Cresol red, Methyl orange |

[95]

[90] |

| Lemna minor L. |

Dye |

Basic Red 46 dye |

[17] |

| Juncus effusus |

Dye |

Methyl Red and Methylene Blue |

[102] |

| Pistia stratiotes L, Salvinia adnata Desv, and Hydrilla verticillata (L.f) |

Dye |

Dyeing effluent |

[2] |

| Ceratophyllum demersum and Lemna gibba |

Heavy metals |

Pb and Cr |

[1] |

| Duckweed (Lemna minor) |

Heavy metals |

As, Hg, Pb, Cr, Cu, and Zn |

[77] |

| Duckweed (Lemna minor) |

Heavy metals |

Pb, Cd, Cu, Cr and Zn |

[90] |

| Duckweed (Lemna minor) |

Heavy metals |

Cd |

[103] |

| Hyacinth (E. crassipes) |

Heavy metals |

Cd, As and Hg |

[70] |

| Vetiveria zizanioides, Phragmites australis, Eichhornia crassipes, Pistia stratiotes, Ipomoea aquatica, Nypa fruticans and Enhydra fluctuans |

Heavy metals |

Pb, Cr, Ni, Zn, Cu, As, Cd and Fe |

[21] |

| Pteris vittata and Pityrogramma calomelanos |

Heavy metals |

As |

[10] |

| Lemna minor (L. minor), Elodea canadensis (E. canadensis) and Cabomba aquatica (C. aquatica) |

Pesticides |

Copper sulphate (fungicide), flazasulfuron (herbicide) and dimethomorph (fungicide) |

[76] |

| E. crassipes, L. minor, and Elodea canadensis |

Pesticides |

Atrazine, Carbendazim, Chlorpyrifos, Coumaphos, Diazinon, Ethoprophos, Linuron, Parathion, Prochloraz |

[26] |

| Hyacinth (E. crassipes) |

Pesticides |

Ethion |

[109] |

| Water Lettuce (Pistia stratiotes L.) and Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) |

Pesticides |

Chlorpyrifos |

[80] |

| Typha spp |

Pharmaceuticals |

Ibuprofen, Carbamazepine and Clofibric acid |

[38] |

| Typha, Phragmites, Iris, and Juncus |

Pharmaceuticals |

Ibuprofen and Iohexol |

[111] |

| Vetiver and Phragmites |

Hydrocarbons |

PAHs |

[9] |

| Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, Ceriops candolleana, Kandelia candel, and Rhizophora mucronata |

Salts |

Desalination |

[71] |

| Sporobolus virginicus |

Salts |

Desalination |

[44] |

Although phytoremediation has been proven to be highly effective, policies promoting the development and real-world application of phytoremediation systems remain underemphasized, particularly in developing countries. Phytoremediation has gained increasing recognition in environmental policies across various nations, though the extent of regulatory standardization varies significantly [

66]. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has published guidance documents such as the Phytoremediation Resource Guide [

21] and Selecting and Using Phytoremediation for Site Cleanup [

36], while the Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council (ITRC) offers technical and regulatory decision trees to support implementation.

The European Union encourages phytoremediation through directives like the Water Framework Directive [

39]and the Groundwater Directive, and provides technical standards such as EN ISO 17402:2011 for assessing pollutant bioavailability. The United Kingdom incorporates phytoremediation within the Contaminated Land Exposure Assessment (CLEA) risk assessment framework, and China recognizes it as a potential remediation approach under its Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law. Regional initiatives, such as those in the Baltic region, also provide guidance on phytoremediation practices.

Despite these advances, many countries still lack comprehensive design standards and implementation frameworks, highlighting the need for a unified design approach to facilitate policy integration and expand the practical use of phytoremediation technologies. In developing countries, phytoremediation is attracting attention due to its low cost and eco-friendly nature; however, large-scale application remains limited. Common challenges include inadequate funding, limited technical expertise, and the absence of regulatory frameworks [

73]. Some nations, such as India [

87], Vietnam [

10], and certain parts of Africa [

67], have implemented small-scale projects using native plant species such as Pteris vittata, Brassica juncea, and Vetiver grass [

94]. However, these initiatives are often not scalable or integrated into national strategies. Greater support is needed in the form of capacity-building, policy development, and incorporation into environmental planning to enable the broader adoption of phytoremediation across these regions.

The objective of this study is to systematically review and evaluate existing research on phytoremediation of contaminants in soil and water, with particular emphasis on key environmental parameters, plant species selection, and system design factors that influence remediation effectiveness. The study also examines current policy frameworks and real-world implementations across different countries.

Ultimately, this review aims to support the development of a standardized design framework and environmental guidelines that can inform and harmonize national strategies. By doing so, it seeks to promote the wider adoption of phytoremediation technologies as a sustainable, cost-effective solution for pollution control, particularly in regions where conventional remediation methods are either financially prohibitive or ecologically disruptive.

2. Application status of phytoremediation

Over the past two decades, phytoremediation has emerged as a promising and sustainable approach for remediating contaminated environments, particularly in areas affected by industrialization, mining, and agricultural runoff [

7,

79]. Despite its scientific maturity and ecological advantages, the application of phytoremediation varies significantly across regions due to differences in environmental policies, technological readiness, and socio-economic priorities [

18,

23,

74,

92,

107].

In North America and Europe, countries such as the United States, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands have advanced phytoremediation beyond laboratory research into pilot-scale and full-scale remediation projects. For instance, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officially recognizes phytoremediation as a viable method for treating heavy metals and organic pollutants, especially at Superfund and brownfield sites [

87]. In Germany, successful use of species like Salix (willows) and Populus (poplars) for remediation of cadmium- and zinc-contaminated soils has influenced broader land-use rehabilitation strategies, integrating phytoremediation into environmental management policies [

14,

81].

In Asia, countries such as China and India face severe environmental contamination from mining and industrial activities. Both nations are actively researching and gradually adopting phytoremediation. China has invested heavily in identifying hyperaccumulator plants like Pteris vittata for arsenic removal [

32,

112], while India has demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of species such as Vetiveria zizanioides and Brassica juncea for remediation of lead- and chromium-contaminated soils through field trials [

66,

93]. Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand and Vietnam, have initiated phytoremediation projects in response to heavy metal pollution from craft villages and agricultural runoff, although these remain limited in scale and are hindered by the absence of standardized frameworks for design and implementation [

21,

55].

In Latin America and Africa, phytoremediation is an area of growing interest but remains largely exploratory. Countries like Brazil and Chile focus on native plants adapted to local contamination, especially in mining-affected zones [

5,

23,

63,

64,

77,

92]. Similarly, Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa have launched research programs on phytoremediation; however, practical application is restricted by limited financial resources, low policy support, and insufficient technical expertise [

17,

25,

60,

75].

Despite these regional advances, global challenges persist, including the lack of standardized protocols for system design, plant selection, and performance evaluation; variability in climatic, soil, and hydrological conditions that complicate replicability; and limited integration of phytoremediation into national remediation policies, which results in inconsistent funding and oversight [

81,

96].

Recognizing these challenges, international organizations such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) emphasize the role of green remediation technologies, including phytoremediation, in meeting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

42,

100]. The creation of transnational networks and knowledge-sharing platforms is critical to accelerating the global adoption of phytoremediation. Bridging scientific advances with coherent policy frameworks is essential for realizing the full potential of phytoremediation as a sustainable environmental management tool worldwide.

3. Current Design Approaches in Phytoremediation Systems

Phytoremediation, the use of plants to remove, stabilize, or degrade environmental pollutants, has been recognized as a sustainable and cost-effective remediation technology. As the method transitions from experimental applications to field-scale deployment, the need for standardized design approaches becomes increasingly apparent [

56]. Standardization not only ensures consistent performance and replicability across sites but also facilitates regulatory approval, stakeholder confidence, and technology transfer.

One of the fundamental design components is plant species selection, which must be standardized based on pollutant type, site characteristics, and ecological compatibility [

56,

57]. Currently, choices often rely on local experience or ad hoc criteria. However, the development of standardized selection protocols, incorporating plant tolerance thresholds, accumulation capacity, and growth rates, can improve system predictability and allow better comparison across projects [

68]. Creating reference databases of approved phytoremediation species for specific contaminants would be a significant step toward harmonized practice.

Similarly, spatial and structural design elements of phytoremediation systems, such as planting density, configuration (e.g., buffer strips, wetland cells), and rooting depth, are often determined on a case-by-case basis. Standardizing these parameters based on site typology (e.g., landfill leachate treatment vs. heavy metal-contaminated soil) would enhance the scalability of phytoremediation technologies [

16]. Engineering guidelines can support practitioners in implementing designs that optimize hydraulic flow, root-zone contact time, and biomass productivity.

Soil and substrate amendments, which enhance contaminant bioavailability and plant health, also require harmonized application protocols. Currently, the use of materials such as biochar, compost, or chelating agents varies widely in composition and dosage [

104,

113]. Establishing best practice standards, including dosage guidelines, environmental risk assessments, and quality criteria, would improve both safety and effectiveness.

In systems targeting groundwater or leachate treatment, hydrological design is critical. Standardized configurations for flow direction, water retention time, and drainage systems can help ensure that contaminants are adequately exposed to plant roots and associated microbial communities. Moreover, these standards would facilitate regulatory assessment of system performance under different climatic and hydrological conditions.

To ensure long-term success, monitoring and maintenance protocols must also be standardized. Uniform guidelines for sampling frequency, contaminant analysis, plant biomass harvesting, and health indicators are needed to assess system functionality and environmental safety. The integration of remote sensing and GIS tools into standard monitoring protocols offers a promising approach for large-scale applications [

74].

In conclusion, while phytoremediation remains a flexible and adaptive technology, the advancement of standardized design frameworks is essential to unlock its full potential. A harmonized approach would bridge the gap between research innovation and practical implementation, enabling broader acceptance of phytoremediation as a viable tool in national and international environmental remediation strategies.

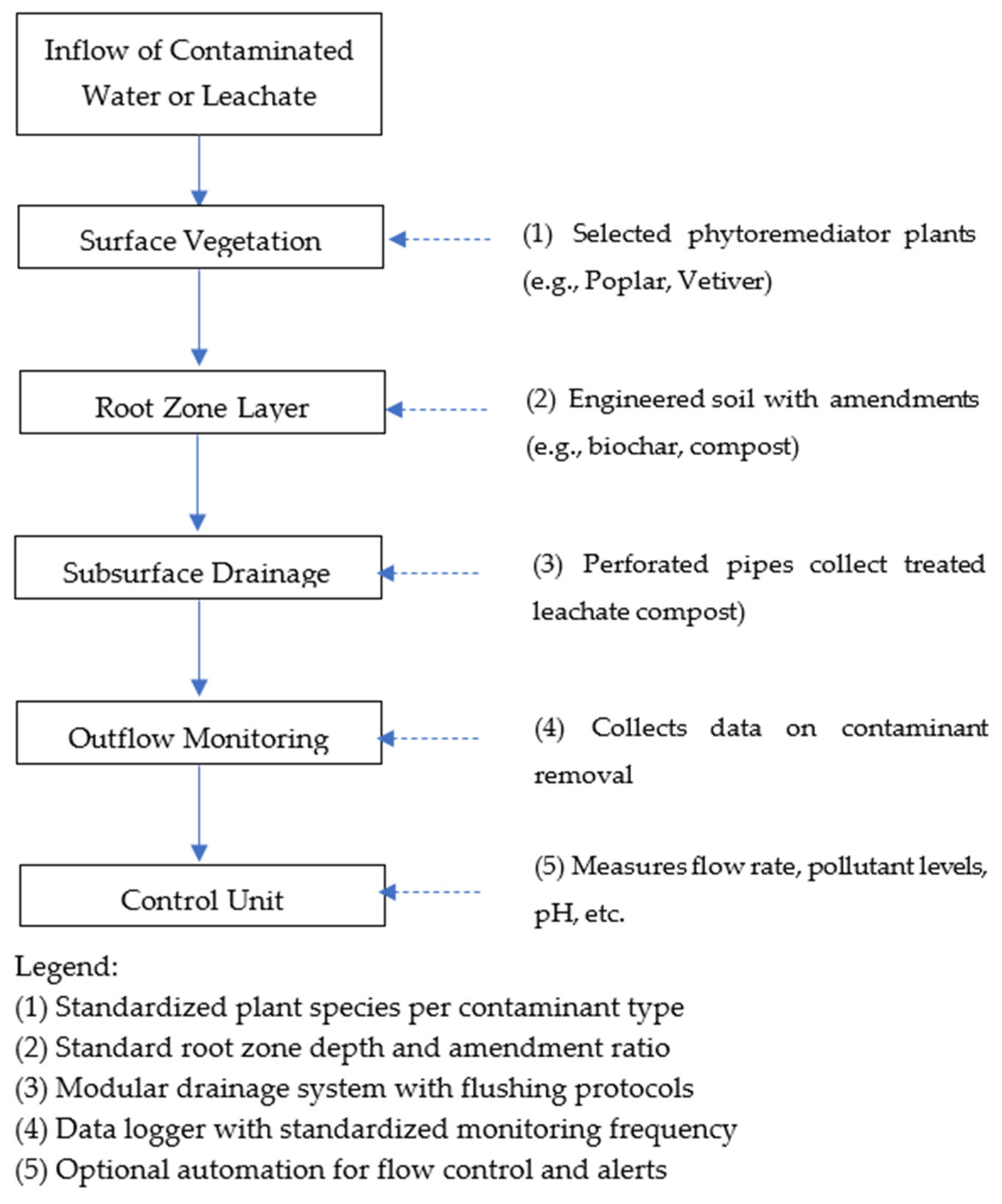

Figure 1.

Schema of standard phytoremediation system.

Figure 1.

Schema of standard phytoremediation system.

Plant species are selected based on a standardized catalog that aligns with the type of pollutant targeted. The root zone depth and the type of soil amendment materials, such as biochar or organic compost, are applied at predetermined ratios. The subsurface drainage layer follows an engineered design that ensures ease of maintenance and potential reuse. An outlet monitoring station is installed to record treatment performance according to standardized sampling frequencies. Additionally, an optional automated control unit is integrated to collect real-time data and issue alerts when parameters exceed threshold limits.

4. Critical Environmental Factors Affecting Phytoremediation Efficiency

Water plays a central role in phytoremediation systems, particularly in designs aimed at treating contaminated wastewater, surface runoff, or groundwater. The quality, quantity, and dynamics of water within these systems significantly influence contaminant mobility, plant health, and microbial activity. To enhance the reliability and scalability of phytoremediation, there is an increasing need to standardize key water-related environmental parameters across various applications and site conditions.

The chemical composition of the water, such as pH, electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO), nutrient concentrations (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus), and presence of heavy metals or organic pollutants, directly affects contaminant bioavailability and plant uptake mechanisms. Standardizing baseline water quality assessments (e.g., pH 6.0–8.0, DO ≥ 5 mg/L) and defining threshold values for phytotoxicity would ensure consistent treatment performance across systems.

Table 2.

Water Chemical Parameters and Proposed Standardized Values for Phytoremediation.

Table 2.

Water Chemical Parameters and Proposed Standardized Values for Phytoremediation.

| Parameter |

Unit |

Proposed Value |

Significance and Notes |

Ref. |

| pH |

– |

6.0 – 8.0 |

A neutral pH range optimizes metal uptake and microbial activity. |

[7,46,93] |

Electrical

Conductivity (EC)

|

µS/cm |

≤ 2500 |

High values may indicate salinity or ionic pollution, which can affect plant health. |

[11,22,111] |

Dissolved

Oxygen (DO)

|

mg/L |

≥ 5.0 |

Essential for root and microbial respiration in the rhizosphere. |

[54,105] |

|

Nitrate (NO₃⁻)

|

mg/L |

≤ 10 |

High concentrations can lead to eutrophication; plants can absorb and reduce the load. |

[11,27,53,54] |

|

Phosphate (PO₄³⁻)

|

mg/L |

≤ 0.1 |

Limited to prevent eutrophication; aquatic plants can absorb it effectively. |

[9,27] |

| Cadmium (Cd) |

µg/L |

≤ 5 |

Highly toxic; must be controlled to avoid harm to plants and aquatic life. |

[11,103] |

| Lead (Pb) |

µg/L |

≤ 10 |

Highly toxic; plants can absorb and accumulate it in tissues. |

[1,8,12,14,46,78] |

| Arsenic (As) |

µg/L |

≤ 10 |

Highly toxic; must be regulated to ensure ecological safety. |

[11,22,81,90] |

| Zinc (Zn) |

µg/L |

≤ 5000 |

Essential in trace amounts; high levels can be phytotoxic. |

[34,55] |

| Copper (Cu) |

µg/L |

≤ 2000 |

Essential in trace amounts; high concentrations may be toxic to plants. |

[27,34] |

The rate at which water is introduced into the system influences retention time, contaminant contact with the rhizosphere, and oxygen levels. Overloading can reduce treatment efficiency and cause plant stress. A standardized HLR range (e.g., 2–10 cm/day for constructed wetlands) could guide the dimensioning of phytoremediation units and ensure optimal hydraulic conditions for different plant species and contaminant types.

Table 3.

Proposed Hydraulic Loading Rates (HLR) for Phytoremediation Systems.

Table 3.

Proposed Hydraulic Loading Rates (HLR) for Phytoremediation Systems.

| System Type |

Recommended HLR |

Reference Source |

| Horizontal Subsurface Flow Wetland (HSSF) |

2–10 cm/day |

[21,50,54,101] |

| Vertical Subsurface Flow Wetland (VSSF) |

5–20 cm/day |

[50,54,106] |

| Municipal Wastewater Treatment System |

0.2–0.5 m³/m²/day |

[21,22,101] |

| Domestic Wastewater Treatment System |

0.15–0.3 m³/m²/day |

[20,52,83,85,91,105,106] |

| Light Industrial Wastewater Treatment System |

0.1–0.25 m³/m²/day |

[85,89,106] |

When applying Hydraulic Loading Rate (HLR), it is essential to adjust the rate according to the specific type of phytoremediation system and treatment objectives to ensure optimal performance. An excessively high HLR can lead to insufficient water retention time, reducing contaminant removal efficiency and causing stress to plants. Conversely, a very low HLR may result in the accumulation of pollutants and decreased treatment effectiveness due to oxygen deficiency and limited microbial activity. Additionally, climatic conditions and the plant species used significantly influence the optimal HLR, and these factors should be carefully considered during system design.

Whether water is applied continuously, intermittently, or in pulses affects root oxygenation, microbial activity, and system resilience. Standardizing operational modes and recommending flow regimes tailored to system type (e.g., horizontal vs. vertical flow wetlands) would help stabilize treatment performance under variable loading.

Table 4.

Effects of Flow Regimes on Phytoremediation System Performance.

Table 4.

Effects of Flow Regimes on Phytoremediation System Performance.

| Flow Regime |

Characteristics |

Impact on System |

Design Recommendations |

Ref. |

| Continuous |

Water is continuously supplied to the system. |

Maintains a stable environment for microorganisms.

– May lead to reduced dissolved oxygen in the rhizosphere. |

Suitable for horizontal subsurface flow (HSSF) systems.

– Ensure natural aeration or oxygen supplementation. |

[15,21,101] |

| Intermittent |

Water is supplied in cycles, with resting periods between doses. |

Enhances oxidation in the rhizosphere.

– Stimulates aerobic microbial activity.

– Reduces clogging risks. |

Suitable for vertical subsurface flow (VSSF) systems.

– Requires timing control for water dosing. |

[107,113] |

| Pulsed |

Water is delivered in short bursts, creating brief, intense flows. |

Improves water and oxygen distribution.

– Increases contact efficiency between water and root zone. |

Requires precise pumping and control systems.

– Suitable for high-load treatment in short periods. |

[37] |

The selection of an appropriate flow regime depends on the type of system, the nature of the contaminants to be treated, and the specific environmental conditions. Vertical subsurface flow systems (VSSF) commonly employ intermittent or pulsed flow modes to enhance oxygenation and microbial activity, whereas horizontal subsurface flow systems (HSSF) typically operate under continuous flow to maintain stable conditions. Standardizing flow regimes and ensuring proper system design are crucial steps to optimize treatment efficiency and support long-term system sustainability.

Temperature plays a key role in the effectiveness of phytoremediation systems, influencing plant metabolism, microbial activity, and the solubility of contaminants. In cooler climates, treatment efficiency is often lower due to slower biological processes. Including recommended operational temperature ranges (e.g., 15–35°C) in standardized guidelines helps define seasonal expectations and guide the selection of appropriate plant species. Below is a summary table showing how different water temperature ranges affect treatment performance and which plant species are best suited to each range.

Table 5.

Summary of Temperature Effects on Treatment Efficiency and Suitable Plant Species.

Table 5.

Summary of Temperature Effects on Treatment Efficiency and Suitable Plant Species.

| Temperature Range (°C) |

Impact on Treatment Efficiency |

Suitable Plant Species |

Ref. |

| < 15°C |

Reduced plant and microbial metabolic rates. – Lower removal efficiency for organic pollutants and heavy metals. |

Egeria densa, Ludwigia natans, Eleocharis acicularis

|

[31,47,51,62] |

| 15–20°C |

Beginning of enhanced biological activity. – Slight improvement in treatment performance. |

Eichhornia crassipes (water hyacinth), Pistia stratiotes (water lettuce) |

[23,85] |

| 20–30°C |

Optimal range for most species. – Enhanced uptake of heavy metals and organics. – Increased microbial and enzymatic activity. |

Typha latifolia (cattail), Ricciocarpus natans, Arundo donax (giant reed), Eichhornia crassipes

|

[3,24] |

| > 30°C |

Reduced performance due to heat stress. – Lower metal uptake. – Inhibited microbial and enzymatic processes. |

Some heat-tolerant species like Arundo donax, but require close monitoring. |

[24,31,47,51] |

The optimal temperature range for phytoremediation is considered to be 20–30°C, with peak heavy metal uptake observed at 25–30°C (TechScience.com, 2022). When temperatures exceed 30°C, many species such as Eichhornia crassipes may experience heat stress, resulting in reduced treatment performance (ResearchGate, 2023). Therefore, choosing plant species suitable for the local temperature conditions is critical to maintaining the system's effectiveness.

To ensure the effective and comparable application of phytoremediation technologies across different sites, the establishment of standardized water conditions is crucial. This involves implementing baseline water quality testing protocols to support informed site selection and ongoing system monitoring. Additionally, it is necessary to define acceptable ranges for critical water parameters, including pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity (EC), and nutrient concentrations. Developing comprehensive guidance documents that align hydraulic and flow design with water characteristics and treatment objectives will further enhance system performance. Moreover, promoting the creation of reference databases that document contaminant removal efficiencies by various plant species under specific water conditions will provide valuable insights for future applications. By integrating these standardized water-related design criteria into phytoremediation planning, the field can achieve more predictable outcomes and facilitate wider adoption as a viable environmental remediation strategy.

5. Contaminant Characteristics

Bioavailability of contaminants is a key factor determining the effectiveness of phytoremediation, as it reflects the extent to which pollutants can be absorbed and metabolized by plants in water or soil environments [

56]. To work toward standardization and future policy development for phytoremediation applications, it is necessary to establish specific regulations for assessing and controlling the bioavailability of contaminants at treatment sites [

52,

86]. Environmental factors such as pH, temperature, soil composition, and the physicochemical properties of the medium must be measured and standardized to ensure bioavailability levels are suitable for maximizing plant uptake and degradation of pollutants [

89]. Additionally, the role of chelating agents and microorganisms in modifying and enhancing bioavailability should be further studied and incorporated into technical guidelines, aiming to optimize treatment conditions and improve the efficiency of phytoremediation [

114]. Establishing these standards will not only ensure consistency in technology implementation but also provide a solid legal foundation for deploying biological pollution treatment projects at national and international levels [

42,

100,

101].

The chemical speciation of contaminants plays an important role in determining the effectiveness of phytoremediation, as different forms, such as ions, organic compounds, or metal complexes, exhibit varying levels of toxicity and plant uptake potential [

96]. To standardize the application and management of this technology, it is essential to develop procedures for identifying and analyzing the chemical forms of pollutants at treatment sites to accurately assess pollution risk and the treatment capacity of plant systems. Furthermore, research on the transformation of contaminant species under different environmental conditions, as well as during the phytoremediation process, must be standardized to ensure proper control and optimization of operational conditions [

7,

56]. Establishing technical standards related to chemical speciation will enhance accuracy in evaluating treatment effectiveness and support the development of environmental management policies, enabling the sustainable, safe, and efficient application of phytoremediation in the future.

The concentration of contaminants in the environment, such as in water, soil, or sediment, is one of the most direct factors influencing the effectiveness of phytoremediation. Determining and standardizing the presence levels of pollutants at treatment locations is essential to ensure that plant systems can operate optimally. Excessive concentrations can cause toxicity or stress in plants, reducing their ability to absorb and degrade contaminants, while concentrations that are too low may fail to adequately trigger effective treatment responses [

89,

96]. Therefore, establishing standards for optimal concentration thresholds for each contaminant type and plant species used in phytoremediation will help guide system selection and design, ensuring sustainability and long-term efficiency of environmental remediation projects. Policies and technical guidelines should be built on scientific data to manage and control contaminant concentrations, thereby facilitating the broad application of phytoremediation technologies in the future.

The interaction among properties such as chemical speciation, bioavailability, and concentration of contaminants plays a decisive role in the performance of plant-based treatment systems in phytoremediation [

7,

114]. The combination of contaminant speciation and bioavailability directly affects the absorption and transformation capacity of plants, while contaminant concentration determines the level of exposure and impact on organisms. Additionally, environmental factors such as pH, temperature, humidity, and the characteristics of the soil or aquatic medium also influence these properties, thereby affecting treatment efficiency and system stability. For practical and sustainable phytoremediation applications, the development of standards and management policies must emphasize integrated evaluation of these interacting factors to optimize operating conditions and ensure the effectiveness of pollution treatment in environmental projects.

6. Post-Harvest Management of Contaminant-Loaded Biomass

Once phytoremediation plants have accumulated pollutants, the harvested biomass becomes a secondary waste stream that must be managed safely and economically. Best practice begins with controlled harvesting schedules that minimize mechanical disturbance and prevent re-release of contaminants to water bodies or adjacent soil [

7,

80]. Immediately after harvest, biomass should be characterized for total contaminant load, moisture content, and calorific value to determine an appropriate end-of-life pathway [

87].

Secure Containment and Disposal – For biomass containing high levels of persistent or highly toxic elements (e.g., Hg, Cd, Pb), secure landfill disposal or hazardous-waste incineration remains the most widely accepted option. Ashes from high-temperature incineration must be stabilized or vitrified before landfilling to avoid leaching.

Thermochemical Conversion – Where metals are present at moderate concentrations, pyrolysis, gasification, or controlled combustion can recover energy and leave a reduced-volume ash that can be further treated. Recent studies show that co-firing Typha latifolia and Eichhornia crassipes with conventional biomass can yield renewable heat while concentrating metals into an ash phase for recycling or secure disposal [

3].

Phytomining and Metal Recovery – Hyperaccumulator biomass rich in Ni, Zn, or Au can be processed to recover valuable metals through smelting or bio-hydrometallurgical leaching. Pilot projects using Pteris vittata for As and Brassica juncea for Pb recovery demonstrate technical feasibility, although economic viability depends on metal market prices and biomass logistics [

13,

87].

Composting and Biochar Production – For biomass primarily laden with nutrients or low-toxicity organics, composting can recycle organic matter, provided periodic leachate monitoring confirms contaminant levels remain below agronomic thresholds. Alternatively, converting biomass to biochar via low-temperature pyrolysis immobilizes many metals and generates a sorptive material useful for further water treatment [

104].

Carbon Sequestration and Ecosystem Services – Fast-growing species such as willow and poplar can be harvested in short rotations; their incorporation into bioenergy-carbon-capture chains contributes to negative-emission strategies while safely removing pollutants from aquatic systems [

85].

Regulatory Alignment – National waste regulations should classify phytoremediation biomass based on contaminant thresholds, specify transport and storage protocols, and set emission limits for thermochemical processing. Harmonized criteria will streamline permitting and assure public safety [

53,

100].

Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) – Incorporating LCA into design guidelines helps compare disposal routes on the basis of greenhouse-gas emissions, resource recovery, and long-term liability, guiding stakeholders toward the most sustainable option [

108].

Implementing a decision matrix that matches contaminant profile, biomass quantity, and local infrastructure with the best end-use pathway will close the loop between phytoremediation and waste management, ensuring that environmental gains are not offset by downstream risks.

7. Implications for Policy and Large-Scale Adoption

7.1. Opportunities for National Environmental Remediation Programs

The standardization of phytoremediation design and processes presents significant opportunities to enhance the effectiveness, reproducibility, and scalability of water treatment systems. Given the diverse nature of water bodies, including rivers, lakes, wetlands, and industrial effluents, each with unique physicochemical characteristics and contamination profiles, establishing a consistent yet adaptable framework is crucial. Such standardization would allow the development of design protocols that accommodate variability while ensuring reliable treatment outcomes.

A key aspect of standardization lies in defining critical design parameters such as the selection of appropriate plant species, planting densities, hydraulic retention times, substrate properties, and nutrient management practices. Clear guidelines on these factors will support system optimization and ease of replication across different contexts. Furthermore, the establishment of standardized protocols for assessing contaminant bioavailability and chemical speciation in water is essential. Uniform analytical methods and reporting formats will enable accurate prediction of phytoremediation potential and facilitate meaningful comparisons across studies and treatment sites.

Monitoring and performance evaluation also benefit from standardization through the adoption of consistent indicators and measurement protocols. Parameters such as contaminant removal efficiency, plant health metrics, and water quality changes should be uniformly assessed to objectively evaluate treatment success and inform ongoing management. Additionally, environmental and operational variables, including temperature, pH, water flow dynamics, and seasonal changes, should be integrated into design frameworks to enhance system resilience and adaptability.

The incorporation of supporting technologies, such as chelating agents, microbial inoculants, and substrate amendments, presents further opportunities for standardizing best practices that maximize contaminant uptake and degradation. Defining when and how to apply these enhancers will improve treatment efficiency and predictability.

Moreover, standardized design and operational guidelines will facilitate technology transfer by providing clear criteria for regulatory approval and compliance. This, in turn, can increase confidence among policymakers, practitioners, and stakeholders, thereby accelerating the adoption of phytoremediation as a mainstream water treatment solution.

Finally, standardization plays a vital role in optimizing cost-effectiveness and risk management. By identifying threshold contaminant concentrations and operational limits, standardized frameworks can guide safe and economically viable applications, ensuring the long-term sustainability of phytoremediation projects at both local and larger scales.

7.2. Integration into Regulatory Guidelines and Sustainability Plans

Integrating phytoremediation into existing regulatory frameworks and sustainability initiatives is essential to promote its widespread and responsible use in water treatment. Currently, many environmental regulations lack specific provisions addressing the application and monitoring of phytoremediation technologies, which can hinder their formal adoption and funding support. Developing clear regulatory guidelines that explicitly recognize phytoremediation as a viable treatment option will provide a legal basis for implementation and ensure consistent quality and safety standards across projects.

Such guidelines should encompass standardized criteria for site assessment, contaminant limits, plant species selection, monitoring protocols, and performance evaluation. Regulatory frameworks must also address potential risks associated with phytoremediation, including the management of biomass containing accumulated contaminants and the prevention of unintended ecological impacts. By incorporating these elements, regulations can help mitigate environmental and human health risks while enabling innovation and flexibility in phytoremediation applications.

Beyond regulation, embedding phytoremediation within broader sustainability and environmental management plans will enhance its role in achieving long-term ecological restoration and pollution control goals. Phytoremediation aligns with principles of green remediation by minimizing chemical inputs and energy consumption, promoting biodiversity, and supporting ecosystem services. Therefore, sustainability plans should explicitly include phytoremediation strategies as part of integrated water resource management, wetland restoration, and contaminated site rehabilitation efforts.

Furthermore, the integration of phytoremediation into sustainability frameworks facilitates cross-sector collaboration among government agencies, researchers, industry, and local communities. It encourages knowledge sharing, capacity building, and the development of pilot projects to demonstrate effectiveness and refine best practices. Such collaborative approaches are crucial for scaling up phytoremediation technologies and ensuring their social acceptance.

In summary, embedding phytoremediation into regulatory guidelines and sustainability plans provides a foundation for standardized, safe, and effective application. It supports environmental policy objectives by advancing innovative treatment solutions that are both economically viable and ecologically responsible, contributing to the sustainable management of water resources and pollution mitigation.

7.3. Recommendations for Policymakers and Stakeholders

To fully realize the potential of phytoremediation as an effective and sustainable water treatment technology, policymakers and stakeholders must take proactive and coordinated actions. Policymakers should prioritize funding for multidisciplinary research focused on improving phytoremediation techniques, including plant selection, contaminant bioavailability enhancement, and system optimization under diverse environmental conditions. Investment in developing standardized methodologies for site assessment, monitoring, and performance evaluation is critical to build a robust evidence base supporting regulatory approval and practical implementation. Stakeholders, including regulatory agencies, scientific communities, and industry experts, should collaborate to create comprehensive technical standards and guidelines that define best practices for phytoremediation design, operation, and monitoring. These standards will help ensure consistency, reliability, and safety across projects, facilitating regulatory acceptance and investor confidence. Raising awareness and building technical expertise among environmental managers, practitioners, and local communities are essential for the successful deployment of phytoremediation. Training programs and knowledge-sharing platforms should be established to equip stakeholders with the necessary skills to design, operate, and maintain phytoremediation systems effectively. Implementing pilot-scale phytoremediation projects in diverse settings can demonstrate the technology’s feasibility, identify operational challenges, and generate site-specific data. Governments and stakeholders should support these initiatives through grants, public-private partnerships, or incentives, enabling adaptive management and refinement of technical approaches. Effective phytoremediation deployment requires coordinated efforts among policymakers, researchers, industry players, non-governmental organizations, and affected communities. Establishing forums and networks to facilitate dialogue, share experiences, and align goals will strengthen cooperation and enhance the technology’s social acceptance and sustainability. Finally, policymakers should explicitly incorporate phytoremediation within national and regional environmental management strategies, pollution control plans, and sustainability agendas. Clear policy frameworks that recognize phytoremediation as a complementary or alternative treatment option will create a supportive environment for innovation and investment. By following these recommendations, policymakers and stakeholders can accelerate the responsible development and scaling of phytoremediation technologies, contributing to improved water quality, ecosystem health, and community well-being.

8. Conclusion

Phytoremediation continues to demonstrate strong potential as an environmentally friendly and cost-effective technology for treating polluted water and soil systems. Its performance is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including contaminant bioavailability, chemical speciation, pollutant concentration, hydrological conditions, temperature, and the selection of site-specific, resilient plant species. To ensure consistent, safe, and effective application, it is imperative to establish standardized design frameworks and technical regulations that reflect these variables.

Importantly, phytoremediation offers an accessible and sustainable solution for pollution control, particularly suited to the needs of developing and low-income countries, where financial and technical resources for conventional remediation may be limited. These countries are strongly encouraged to proactively develop and adopt national standards and operational guidelines for phytoremediation. By doing so, they can integrate this method into their environmental management systems in a way that maximizes local advantages, low cost, low infrastructure requirements, and minimal environmental disruption, while also aligning with global sustainability goals.

Incorporating phytoremediation into national environmental programs opens valuable opportunities for ecological restoration, especially in areas affected by industrial or agricultural contamination. To facilitate this, regulatory frameworks must define environmental suitability criteria, pollutant categories, monitoring protocols, and biomass disposal standards. Managing the contaminated plant biomass after pollutant uptake is also critical, particularly for hazardous elements like Hg, Cd, or Pb, and requires safe disposal methods such as secure landfilling or high-temperature incineration with proper ash stabilization to prevent secondary pollution.

Ultimately, the advancement of phytoremediation calls for a holistic and interdisciplinary approach, combining science, policy, and community engagement. Investments in research, pilot projects, public education, and technical capacity building will be essential. With strategic support, phytoremediation can play a central role in helping both developed and developing nations achieve long-term environmental resilience and pollution mitigation in a sustainable and inclusive manner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Q.N.; project administration, T.Q.N; supervision, T.Q.N. and M.N.T.; writing-original draft, T.M.H., T.Q.N. and M.N.T.; writing-review and editing, T.Q.N., M.N.T. and T.N.N.; data curation, D.H.P., T.N.N. and H.M.T.; formal analysis, D.H.P., T.N.N. and H.M.T.; investigation, T.M.H., H.M.T. and M.Q.B.; validation, T.M.H., M.Q.B. and H.X.N.; resources, M.Q.B. and H.X.N.; software, D.H.P. and H.X.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Center for High Technology Research and Development is appreciated for partly supporting to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Abdallah, M. A. M. (2012). Phytoremediation of heavy metals from aqueous solutions by two aquatic macrophytes, Ceratophyllum demersum and Lemna gibba L. Environmental Technology, 33(14), 1609–1614. [CrossRef]

- Ahila, K. G., Ravindran, B., Muthunarayanan, V., Nguyen, D. D., Nguyen, X. C., Chang, S. W., Nguyen, V. K., & Thamaraiselvi, C. (2020). Phytoremediation Potential of Freshwater Macrophytes for Treating Dye-Containing Wastewater. Sustainability, 13(1), 329. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. (2022). Phytoremediation of heavy metals and total petroleum hydrocarbon and nutrients enhancement of Typha latifolia in petroleum secondary effluent for biomass growth. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(4), 5777–5786. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F., Mohammadkhani, N., & Servati, M. (2022). Halophytes play important role in phytoremediation of salt-affected soils in the bed of Urmia Lake, Iran. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 12223. [CrossRef]

- Akinpelu, E. A., & Nchu, F. (2024). Advancements in Phytoremediation Research in South Africa (1997–2022). Applied Sciences, 14(17), 7660. [CrossRef]

- Al-Baldawi, I. A., Abdullah, S. R. S., Anuar, N., & Hasan, H. A. (2018). Phytotransformation of methylene blue from water using aquatic plant (Azolla pinnata). Environmental Technology & Innovation, 11, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H., Khan, E., & Sajad, M. A. (2013). Phytoremediation of heavy metals, Concepts and applications. Chemosphere, 91(7), 869–881. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Abbas, Z., Rizwan, M., Zaheer, I., Yavaş, İ., Ünay, A., Abdel-DAIM, M., Bin-Jumah, M., Hasanuzzaman, M., & Kalderis, D. (2020). Application of Floating Aquatic Plants in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals Polluted Water: A Review. Sustainability, 12(5), 1927. [CrossRef]

- Alsghayer, R., Salmiaton, A., Mohammad, T., Idris, A., & Ishak, C. F. (2020). Removal Efficiencies of Constructed Wetland Planted with Phragmites and Vetiver in Treating Synthetic Wastewater Contaminated with High Concentration of PAHs. Sustainability, 12(8), 3357. [CrossRef]

- Anh, B. T. K., Ha, N. T. H., Danh, L. T., van Minh, V., & Kim, D. D. (2017). Phytoremediation Applications for Metal-Contaminated Soils Using Terrestrial Plants in Vietnam. In Phytoremediation (pp. 157–181). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Anh, B. T. K., Minh, N. N., Ha, N. T. H., Kim, D. D., Kien, N. T., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. T., & Danh, L. T. (2018). Field Survey and Comparative Study of Pteris Vittata and Pityrogramma Calomelanos Grown on Arsenic Contaminated Lands with Different Soil pH. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 100(5), 720–726. [CrossRef]

- Aryal, M. (2024). Phytoremediation strategies for mitigating environmental toxicants. Heliyon, 10(19), e38683. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Wan, X., Lei, M., Wang, L., & Chen, T. (2023). Research advances in mechanisms of arsenic hyperaccumulation of Pteris vittata: Perspectives from plant physiology, molecular biology, and phylogeny. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 460, 132463. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. J. M., McGrath, S. P., Reeves, R. D. and Smith, J. A. C. 1999. Metal hyperaccumulator plants: a review of the ecology and physiology of a biological resource for phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils. in: Terry, N., Vangronsveld, J. and Banuelos, G. (ed.) Phytoremediation of contaminated soils CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. pp. 85-107.

- Bernardino, C. A. R., Mahler, C. F., Preussler, K. H., & Novo, L. A. B. (2016). State of the Art of Phytoremediation in Brazil, Review and Perspectives. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 227(8), 272. [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, R. v., Boralkar, D. B., & Chavhan, R. D. (2018). Remediation capabilities of pilot-scale wetlands planted with Typha aungstifolia and Acorus calamus to treat landfill leachate. Journal of Ecology and Environment, 42(1), 23. [CrossRef]

- Bharathiraja, B., Jayamuthunagai, J., Praveenkumar, R., & Iyyappan, J. (2018). Phytoremediation Techniques for the Removal of Dye in Wastewater (pp. 243–252). [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. A., Bashir, O., Ul Haq, S. A., Amin, T., Rafiq, A., Ali, M., Américo-Pinheiro, J. H. P., & Sher, F. (2022). Phytoremediation of heavy metals in soil and water: An eco-friendly, sustainable and multidisciplinary approach. Chemosphere, 303, 134788. [CrossRef]

- Boonsaner, M., Borrirukwisitsak, S., & Boonsaner, A. (2011). Phytoremediation of BTEX contaminated soil by Canna×generalis. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 74(6), 1700–1707. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. S., Kreissl, J. S., Gearhart, R. A., Kruzic, A. P., Boyle, W. C., Otis, R. J. et al., Manual - constructed wetlands treatment of municipal wastewaters. EPA/625/R-99/010 (NTIS PB2001-101833), 2000.

- Bruce E. Pivetz. (2001). Phytoremediation of Contaminated Soil and Ground Water at Hazardous Waste Sites (EPA/540/S-01/500). EPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Ground Water Issue.

- Bui, T. K. A., Dang, D. K., Nguyen, T. K., Nguyen, N. M., Nguyen, Q. T., & Nguyen, H. C. (2014). Phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soil and water in Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Environment, 6(1), 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Buta, E., Borșan, I. L., Omotă, M., Trif, E. B., Bunea, C. I., Mocan, A., Bora, F. D., Rózsa, S., & Nicolescu, A. (2023). Comparative Phytoremediation Potential of Eichhornia crassipes, Lemna minor, and Pistia stratiotes in Two Treatment Facilities in Cluj County, Romania. Horticulturae, 9(4), 503. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Cao, X., Liu, B., Lin, H., Luo, H., Liu, F., Su, D., Lv, S., Lin, Z., & Lin, D. (2025). Saline–Alkali Tolerance Evaluation of Giant Reed (Arundo donax) Genotypes Under Saline–Alkali Stress at Seedling Stage. Agronomy, 15(2), 463. [CrossRef]

- Calderon, J. L., Kaunda, R. B., Sinkala, T., Workman, C. F., Bazilian, M. D., & Clough, G. (2021). Phytoremediation and phytoextraction in Sub-Saharan Africa: Addressing economic and social challenges. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 226, 112864. [CrossRef]

- Chander, P. D., Fai, C. M., & Kin, C. M. (2018). Removal of Pesticides Using Aquatic Plants in Water Resources: A Review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 164, 012027. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., Jiang, L., Liu, W., Song, X., Kumpiene, J., & Luo, C. (2024). Phytoremediation of trichloroethylene in the soil/groundwater environment: Progress, problems, and potential. Science of The Total Environment, 954, 176566. [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Tovar, L., Marrugo-Madrid, S., Castro, L. P., Tapia-Contreras, E. E., Marrugo-Negrete, J., & Díez, S. (2025). Exploring the phytoremediation potential of plant species in soils impacted by gold mining in Northern Colombia. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 32(7), 3795–3808. [CrossRef]

- Cristaldi, A., Oliveri Conti, G., Cosentino, S. L., Mauromicale, G., Copat, C., Grasso, A., Zuccarello, P., Fiore, M., Restuccia, C., & Ferrante, M. (2020). Phytoremediation potential of Arundo donax (Giant Reed) in contaminated soil by heavy metals. Environmental Research, 185, 109427. [CrossRef]

- Crum, S. J. H., Kammen-Polman, A. M. M. van, & Leistra, M. (1999). Sorption of Nine Pesticides to Three Aquatic Macrophytes. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 37(3), 310–316. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F. V. da S., Venne, P., Segura, P., & Juneau, P. (2025). Effect of temperature on the physiology and phytoremediation capacity of Spirodela polyrhiza exposed to atrazine and S-metolachlor. Aquatic Toxicology, 282, 107304. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S. D., & Ow, D. W. (1996). Promises and Prospects of Phytoremediation. Plant Physiology, 110(3), 715–719. [CrossRef]

- Cynthia Green and Ana Hoffnagle, Phytoremediation field studies database for chlorinated solvents, pesticides, explosives, and metals, 2004, U.S. EPA report.

- Danh, L. T., Truong, P., Mammucari, R., & Foster, N. (2010). Economic Incentive for Applying Vetiver Grass to Remediate Lead, Copper and Zinc Contaminated Soils. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 13(1), 47–60. [CrossRef]

- de Lima Barizão, A. C., Silva, M. F., Andrade, M., Brito, F. C., Gomes, R. G., & Bergamasco, R. (2020). Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles for tartrazine and bordeaux red dye removal. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 8(1), 103618. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, G., & Shin, P. E. (2001). Brownfields Technology Primer: Selecting and Using Phytoremediation for Site Cleanup (EPA 542-R-01-006).

- Dincau, B., Tang, C., Dressaire, E., & Sauret, A. (2022). Clog mitigation in a microfluidic array via pulsatile flows.

- Dordio, A., Carvalho, A. J. P., Teixeira, D. M., Dias, C. B., & Pinto, A. P. (2010). Removal of pharmaceuticals in microcosm constructed wetlands using Typha spp. and LECA. Bioresource Technology, 101(3), 886–892. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N. K., Kumar, V., & Chandra, R. (2017). Phytoremediation of Environmental Pollutants. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Durjava, M., & Kolar, B. (2023). Bioavailability-based Environmental Quality Standards for metals under the Water Framework Directive. Acta Hydrotechnica, 17–29. [CrossRef]

- El-Sadaawy, M. M., & Agib, N. S. (2024). Removal of Textile dyes by ecofriendly aquatic plants From wastewater: A review on Plants Species, Mechanisms, and Perspectives. Blue Economy, 2(2). [CrossRef]

- FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Fooladi, M., Moogouei, R., Jozi, S. A., Golbabaei, F., & Tajadod, G. (2019). Phytoremediation of BTEX from indoor air by Hyrcanian plants. Environmental Health Engineering and Management, 6(4), 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J. L. (1985). Halophytic crops for cultivation at seawater salinity. Plant and Soil, 89(1–3), 323–336. [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, K. E., Huang, X.-D., Glick, B. R., & Greenberg, B. M. (2009). Phytoremediation and rhizoremediation of organic soil contaminants: Potential and challenges. Plant Science, 176(1), 20–30. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M., & Satendra Pal Singh. (2005). A review on phytoremediation of heavy metals and utilization of its byproducts. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 3(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M. P. (2024). Climate Change and Aquatic Phytoremediation of Contaminants: Exploring the Future of Contaminant Removal. Phyton, 93(9), 2127–2147. [CrossRef]

- Guidi Nissim, W., Castiglione, S., Guarino, F., Pastore, M. C., & Labra, M. (2023). Beyond Cleansing: Ecosystem Services Related to Phytoremediation. Plants, 12(5), 1031. [CrossRef]

- 2013; 49. Hanh DT, Kadokami K, Matsuura N, Trung NQ, Screening analysis of a thousand micro-pollutants in Vietnamese rivers, Southeast Asian Water Environ, 2013, 5.

- Hans Brix. (1997). Do macrophytes play a role in constructed treatment wetlands? Water Science and Technology, 35(5). [CrossRef]

- Haris, H., Fai, C. M., Bahruddin, A. S. binti, & Dinesh, A. A. A. (2018). Effect of Temperature on Nutrient Removal Efficiency of Water Hyacinth for Phytoremediation Treatment. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(4.35), 81. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J., Hogye, S., Frederick, R., Goo, R., & Kelly, S. (2005). US EPA Program strategy for decentralized wastewater systems. Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation, 2005(10), 5795–5801. [CrossRef]

- ITRC (Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council). 2009. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised. PHYTO-3. Washington, D.C.: Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council, Phytotechnologies Team, Tech Reg Update.

- Kadlec, R. H., & Wallace, S. (2008). Treatment Wetlands. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Kaewtubtim, P. (2016). Heavy metal phytoremediation potential of plant species in a mangrove ecosystem in Pattani bay, Thailand. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 14(1), 367–382. [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A., Timilsina, A., Gautam, A., Adhikari, K., Bhattarai, A., & Aryal, N. (2022). Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Environmental Advances, 8, 100203. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H., Kumar, A., Bindra, S., & Sharma, A. (2024). Phytoremediation: An emerging green technology for dissipation of PAHs from soil. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 259, 107426. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. U., Khan, A. N., Waris, A., Ilyas, M., & Zamel, D. (2022). Phytoremediation of pollutants from wastewater: A concise review. Open Life Sciences, 17(1), 488–496. [CrossRef]

- Khandare, R. v., & Govindwar, S. P. (2015). Phytoremediation of textile dyes and effluents: Current scenario and future prospects. Biotechnology Advances, 33(8), 1697–1714. [CrossRef]

- Kola, E., Munyai, C., & Dalu, T. (2025). A review of macrophyte phytoremediation in Africa: current research and challenges. Chemistry and Ecology, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, R. A., Tirtalistyani, R., Tang, Y. Y., Thao, N. T. T., Kasongo, J., & Wijayanti, Y. (2023). Phytoremediation Mechanism for Emerging Pollutants : A Review. Tropical Aquatic and Soil Pollution, 3(1), 88–108. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, H., Qian, Z., Inoue, C., & Chien, M.-F. (2023). Temperature Dependence of Metals Accumulation and Removal Kinetics by Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera. Plants, 12(4), 877. [CrossRef]

- Lazo, A., Lazo, P., Urtubia, A., Lobos, M. G., Hansen, H. K., & Gutiérrez, C. (2022). An Assessment of the Metal Removal Capability of Endemic Chilean Species. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3583. [CrossRef]

- Lazo, P., & Lazo, A. (2020). Assessment of Native and Endemic Chilean Plants for Removal of Cu, Mo and Pb from Mine Tailings. Minerals, 10(11), 1020. [CrossRef]

- Le, T. M., Pham, P. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Bui, M. Q., Nguyen, H. Q., Vu, N. D., Kannan, K., & Tran, T. M. (2022). A survey of parabens in aquatic environments in Hanoi, Vietnam and its implications for human exposure and ecological risk. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(31), 46767–46777. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H., Park, H., & Kim, J.-G. (2023). Current Status of and Challenges for Phytoremediation as a Sustainable Environmental Management Plan for Abandoned Mine Areas in Korea. Sustainability, 15(3), 2761. [CrossRef]

- Malunguja, G. K., & Paschal, M. (2024). Evaluating potential phytoremediators to combat detrimental impacts of mining on biodiversity: a review focused in Africa. Discover Environment, 2(1), 94. [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, T. C. (2003). Databases and Protocol for Plant and Microorganism Selection: Hydrocarbons and Metals. In Phytoremediation (pp. 887–904). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Muthusaravanan, S., Sivarajasekar, N., Vivek, J. S., Paramasivan, T., Naushad, Mu., Prakashmaran, J., Gayathri, V., & Al-Duaij, O. K. (2018). Phytoremediation of heavy metals: mechanisms, methods and enhancements. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 16(4), 1339–1359. [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M., Idrees, I., Idrees, P., Ahmad, S., Ali, Q., & Malik, A. (2020). Potential of water hyacinth (eichhornia crassipes l.) for phytoremediation of heavy metals from waste water. Biological and Clinical Sciences Research Journal, 2020(1). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. T., Le, T. G., Nguyen, T. T., Le, V. N., Hoang, M. T., Truong, N. M., Nguyen, N. T., & Bui, Q. M. (2023). The Deadlock of Application Research Using Halophytes for Seawater Desalination Due to Rapid Evaporation of Water. [CrossRef]

- Nu Nguyen, H. M., Khieu, H. T., Ta, N. A., Le, H. Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Do, T. Q., Hoang, A. Q., Kannan, K., & Tran, T. M. (2021). Distribution of cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes in drinking water, tap water, surface water, and wastewater in Hanoi, Vietnam. Environmental Pollution, 285, 117260. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M., Phelan, T. J., Smith, N. M., & Smits, K. M. (2021). Remediation in developing countries: A review of previously implemented projects and analysis of stakeholder participation efforts. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 51(12), 1259–1280. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M. S., Whipple, A. L., Inman, R. D., Tarbox, B. C., Monroe, A. P., Robb, B. S., & Aldridge, C. L. (2024). Remote sensing for monitoring mine lands and recovery efforts. [CrossRef]

- Odoh, C. K., Zabbey, N., Sam, K., & Eze, C. N. (2019). Status, progress and challenges of phytoremediation - An African scenario. Journal of Environmental Management, 237, 365–378. [CrossRef]

- Olette, R., Couderchet, M., Biagianti, S., & Eullaffroy, P. (2008). Toxicity and removal of pesticides by selected aquatic plants. Chemosphere, 70(8), 1414–1421. [CrossRef]

- Paes, É. de C., Veloso, G. V., de Castro Filho, M. N., Barroso, S. H., Fernandes-Filho, E. I., Fontes, M. P. F., & Soares, E. M. B. (2023). Potential of plant species adapted to semi-arid conditions for phytoremediation of contaminated soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 449, 131034. [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.-M. M., Torres, G., Arenas, A. D., Sánchez, E., & Rodríguez, K. (2012). Phytoremediation of Low Levels of Heavy Metals Using Duckweed (Lemna minor). In Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants (pp. 451–463). Springer New York. [CrossRef]

- Pilon-Smits, E. (2005). PHYTOREMEDIATION. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 56(1), 15–39. [CrossRef]

- Prasertsup, P., & Ariyakanon, N. (2011). Removal of Chlorpyrifos by Water Lettuce (Pistia stratiotes L.) and Duckweed (Lemna minor L.). International Journal of Phytoremediation, 13(4), 383–395. [CrossRef]

- Pulford, I., & Watson, C. (2003). Phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated land by trees, a review. Environment International, 29(4), 529–540. [CrossRef]

- Raskin, I., Smith, R. D., & Salt, D. E. (1997). Phytoremediation of metals: using plants to remove pollutants from the environment. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 8(2), 221–226. [CrossRef]

- Reed, S. C., Crites, R. W., & Middlebrooks, E. J. (1995). Natural Systems for Waste Management and Treatment (2nd Edition). McGraw Hill.

- Riccioli, F., Guidi Nissim, W., Masi, M., Palm, E., Mancuso, S., & Azzarello, E. (2020). Modeling the Ecosystem Services Related to Phytoextraction: Carbon Sequestration Potential Using Willow and Poplar. Applied Sciences, 10(22), 8011. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Z. F., Jamal, M., Parveen, H., Sarfraz, W., Nasreen, S., Khalid, N., & Muzammil, K. (2024). Phytoremediation potential of Pistia stratiotes, Eichhornia crassipes, and Typha latifolia for chromium with stimulation of secondary metabolites. Heliyon, 10(7), e29078. [CrossRef]

- Rock, S, Pivetz B., Madalinski, K., Adams, N., Wilson T., Introduction to phytoremediation, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., EPA/600/R-99/107 (NTIS PB2000-106690), 2000.

- Salido, A. L., Hasty, K. L., Lim, J.-M., & Butcher, D. J. (2003). Phytoremediation of Arsenic and Lead in Contaminated Soil Using Chinese Brake Ferns (Pteris vittata ) and Indian Mustard (Brassica juncea ). International Journal of Phytoremediation, 5(2), 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Salt, D. E., Smith, R. D., & Raskin, I. (1998). PHYTOREMEDIATION. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 49(1), 643–668. [CrossRef]

- Sawarkar, R., Shakeel, A., Kumar, T., Ansari, S. A., Agashe, A., & Singh, L. (2023). Evaluation of plant species for air pollution tolerance and phytoremediation potential in proximity to a coal thermal power station: implications for smart green cities. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 45(10), 7303–7322. [CrossRef]

- Sekomo, C. B., Rousseau, D. P. L., Saleh, S. A., & Lens, P. N. L. (2012). Heavy metal removal in duckweed and algae ponds as a polishing step for textile wastewater treatment. Ecological Engineering, 44, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., Saini, H., Paul, D. R., Chaudhary, S., & Nehra, S. P. (2021). Removal of organic dyes from wastewater using Eichhornia crassipes: a potential phytoremediation option. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(6), 7116–7122. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. da, Rosa, G. B., Sganzerla, W. G., Ferrareze, J. P., Simioni, F. J., & Campos, M. L. (2023). Strategies and prospects in the recovery of contaminated soils by phytoremediation: an updated overview. Communications in Plant Sciences, 13(2023). [CrossRef]

- Singh, V., Thakur, L., & Mondal, P. (2015). Removal of Lead and Chromium from Synthetic Wastewater Using Vetiveria zizanioides. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water, 43(4), 538–543. [CrossRef]

- Siyar, R., Doulati Ardejani, F., Farahbakhsh, M., Norouzi, P., Yavarzadeh, M., & Maghsoudy, S. (2020). Potential of Vetiver grass for the phytoremediation of a real multi-contaminated soil, assisted by electrokinetic. Chemosphere, 246, 125802. [CrossRef]

- Tan, K. A., Morad, N., & Ooi, J. Q. (2016). Phytoremediation of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange Using Eichhornia crassipes. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 7(10), 724–728. [CrossRef]

- Tangahu, B. V., Sheikh Abdullah, S. R., Basri, H., Idris, M., Anuar, N., & Mukhlisin, M. (2011). A Review on Heavy Metals (As, Pb, and Hg) Uptake by Plants through Phytoremediation. International Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2011(1). [CrossRef]

- Tarla, D. N., Erickson, L. E., Hettiarachchi, G. M., Amadi, S. I., Galkaduwa, M., Davis, L. C., Nurzhanova, A., & Pidlisnyuk, V. (2020). Phytoremediation and Bioremediation of Pesticide-Contaminated Soil. Applied Sciences, 10(4), 1217. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, H. T., Marcussen, H., Hansen, H. C. B., Le, G. T., Duong, H. T., Ta, N. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Hansen, S., & Strobel, B. W. (2017). Screening of inorganic and organic contaminants in floodwater in paddy fields of Hue and Thanh Hoa in Vietnam. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(8), 7348–7358. [CrossRef]

- Truong, D. A., Trinh, H. T., Le, G. T., Phan, T. Q., Duong, H. T., Tran, T. T. L., Nguyen, T. Q., Hoang, M. T. T., & Nguyen, T. van. (2023). Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of organophosphate esters in surface water from rivers and lakes in urban Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere, 331, 138805. [CrossRef]

- UN Environment (2019). Global Environment Outlook – GEO-6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People. Nairobi. DOI 10.1017/9781108627146.

- UN-HABITAT. (2008). Constructed Wetlands Manual. UN-HABITAT Water for Asian Cities Programme Nepal.

- Urucu, O. A., Garosi, B., & Musah, R. A. (2025). Efficient Phytoremediation of Methyl Red and Methylene Blue Dyes from Aqueous Solutions by Juncus effusus. ACS Omega, 10(2), 1943–1953. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, Y., & Taner, F. (2010). Bioremoval of Cadmium by Lemna minor in Different Aquatic Conditions. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water, 38(4), 370–377. [CrossRef]

- Virú-Vasquez, P., Pilco-Nuñez, A., Tineo-Cordova, F., Madueño-Sulca, C. T., Quispe-Ojeda, T. C., Arroyo-Paz, A., Alvarez-Arteaga, R., Velasquez-Zuñiga, Y., Oscanoa-Gamarra, L. L., Saldivar-Villarroel, J., Césare-Coral, M. F., & Nuñez-Bustamante, E. (2025). Integrated Biochar–Compost Amendment for Zea mays L. Phytoremediation in Soils Contaminated with Mining Tailings of Quiulacocha, Peru. Plants, 14(10), 1448. [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. (2010). Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Water, 2(3), 530–549. [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J., & Kröpfelová, L. (2008). Wastewater Treatment in Constructed Wetlands with Horizontal Sub-Surface Flow (Vol. 14). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Sheng, L., & Xu, J. (2021). Clogging mechanisms of constructed wetlands: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 295, 126455. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., & Aghajani Delavar, M. (2023). Techno-economic analysis of phytoremediation: A strategic rethinking. Science of The Total Environment, 902, 165949. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H., & Ma, X. (2006). Phytoremediation of ethion by water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) from water. Bioresource Technology, 97(8), 1050–1054. [CrossRef]

- Yan, A., Wang, Y., Tan, S. N., Mohd Yusof, M. L., Ghosh, S., & Chen, Z. (2020). Phytoremediation: A Promising Approach for Revegetation of Heavy Metal-Polluted Land. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Lv, T., Carvalho, P. N., Arias, C. A., Chen, Z., & Brix, H. (2016). Removal of the pharmaceuticals ibuprofen and iohexol by four wetland plant species in hydroponic culture: plant uptake and microbial degradation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(3), 2890–2898. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F., Han, Y., Shi, H., Wang, G., Zhou, M., & Chen, Y. (2023). Arsenic in the hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata: A review of benefits, toxicity, and metabolism. Science of The Total Environment, 896, 165232. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Zhu, W., & Tong, W. (2009). Clogging processes caused by biofilm growth and organic particle accumulation in lab-scale vertical flow constructed wetlands. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 21(6), 750–757. [CrossRef]

- Zulkernain, N. H., Uvarajan, T., & Ng, C. C. (2023). Roles and significance of chelating agents for potentially toxic elements (PTEs) phytoremediation in soil: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 341, 117926. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).