1. Introduction

When a star dies, it undergoes a contraction and blows off its outer envelope, forming a planetary nebula [

6,

7]. If the star collapses to within its Schwarzschild radius, it forms a black hole [

8]. Newton’s law of universal gravitation [

1] provides the equation for this force, which states that:

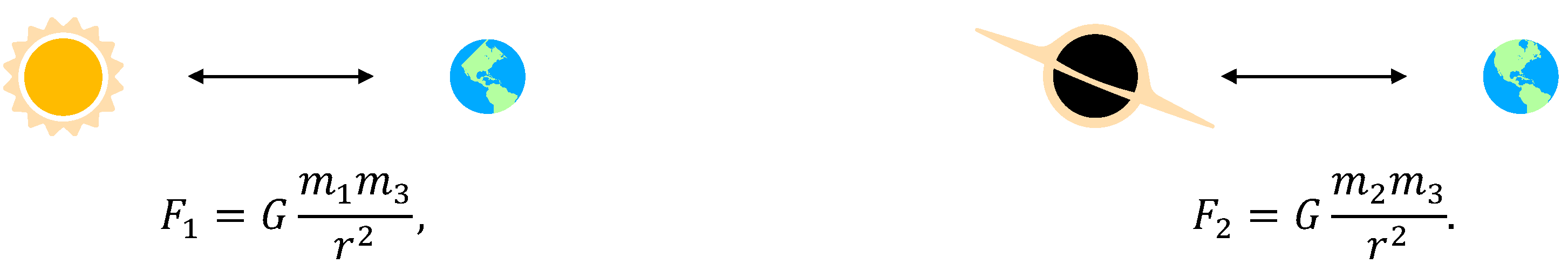

Figure 1.

A star forms a black hole.

Figure 1.

A star forms a black hole.

Before the star collapses, the gravitational force between the planet and the star is represented by

. After the collapse, the gravitational force between the planet and the black hole is represented by

. In these equations,

represents the mass of the star,

represents the mass of the black hole,

represents the mass of the planet,

represents the distance between their centers of mass, and

is the gravitational constant. The gravitational force of a black hole is extremely strong and nothing, not even light, can escape it [

9]. Therefore,

is greater than

. As the star collapses into a black hole, it blows off its outer envelope and loses mass [

10]. Assuming the star loses

of its mass during this process, the mass of the black hole can be represented as

of

. This can be rewritten as:

When the common parameters are removed, the equation can be simplified to:

How is it even possible that

is less than

? As the mass decreases from

to

and the distance

between the objects remains unchanged, it suggests that the gravitational constant

has increased. In Einstein’s theory of relativity, matter curves spacetime, and the Einstein field equations [

4] can be expressed in the following form:

In this equation, is the Einstein tensor and is the gravitational constant. However, if the gravitational constant is constantly changing, it raises the question of whether Einstein’s theory is still accurate.

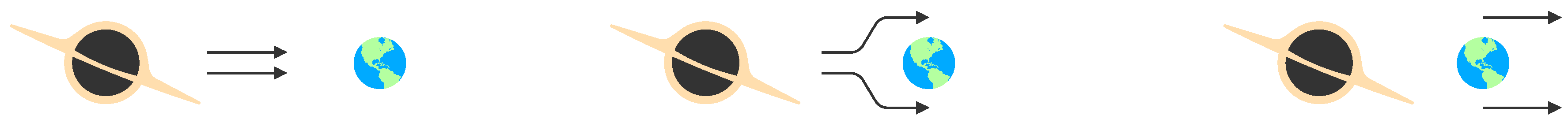

2. Model

What if the situation were reversed, and both matter and energy were converted from curved space? Matter can release energy through annihilation, fission, and fusion [

2,

3], as matter and energy are different forms of the same thing. Therefore, matter curves spacetime because it is converted from curved space, and the flow of space released by matter creates gravitational force. The greater the amount of space released, the stronger the gravitational force generated. If one object releases much more space than another object, the flow of space will narrow the distance between the two objects. It is the space that moves, not the objects.

When two galaxies are very far apart, the space they release accumulates in the middle, and this expands their distance. Therefore, the expansion of the universe and the phenomenon of redshift [

11] are caused by the increase in space.

Figure 3.

Expansion of the universe.

Figure 3.

Expansion of the universe.

Thus, space curves in one dimension, converting matter and energy.

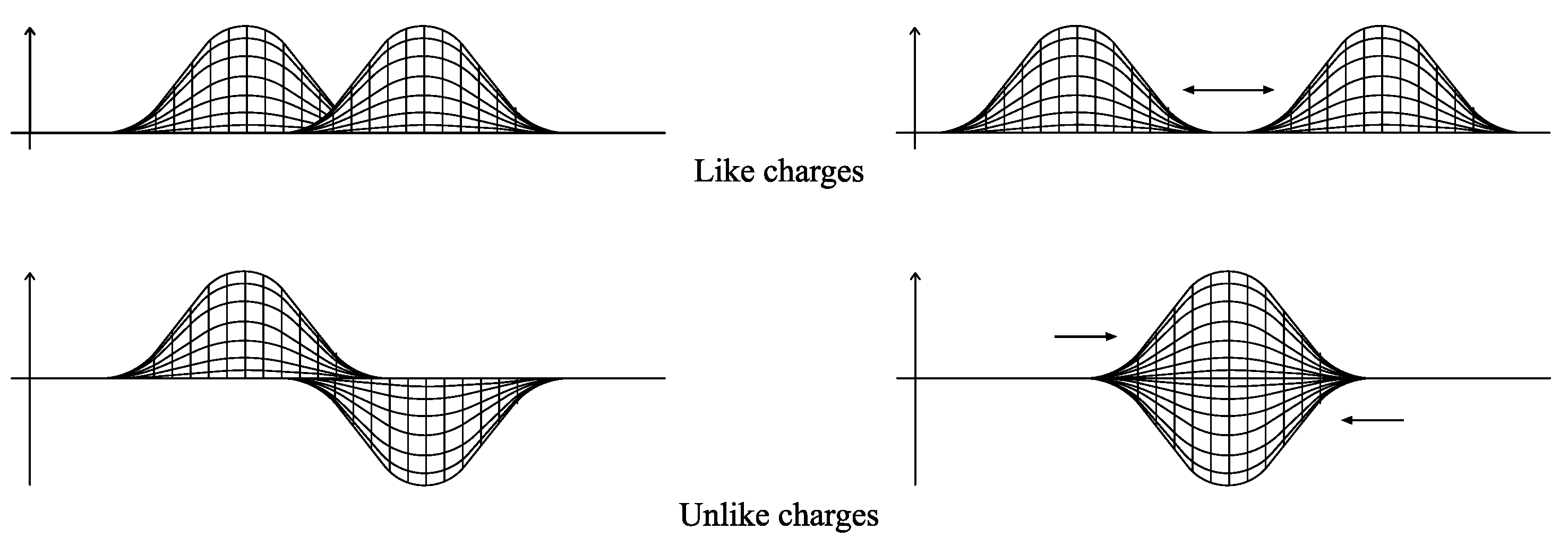

Since an electron is matter and there are only two directions in one dimension, matter curves in two different directions, creating two types of electric charges: positive and negative. Like charges repel each other because they occupy the same position in one dimension, while unlike charges attract each other because they occupy opposite positions in one dimension. Since they are all matter, they can only attract or repel each other, not annihilate.

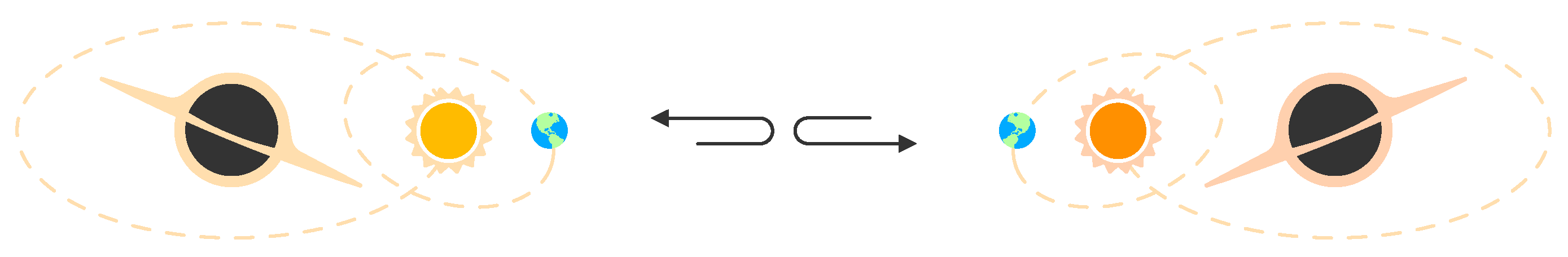

Figure 5.

Electric charges.

Figure 5.

Electric charges.

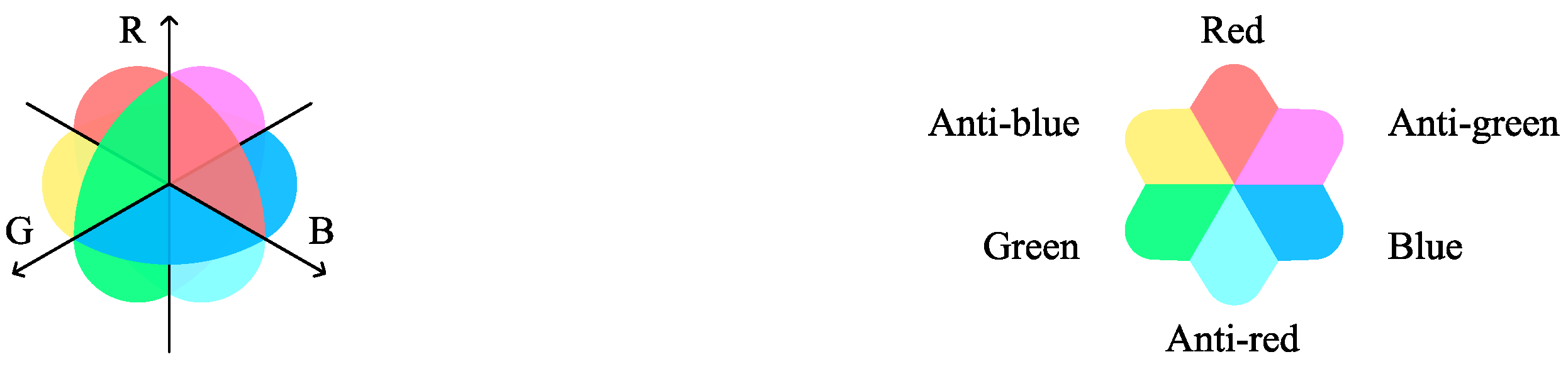

Quarks have three color charges: red, green, and blue [

12], which are converted by matter curving in three different dimensions. The experimental discovery of neutrino oscillation [

13,

14,

15] proves that those three values of quark color can be converted into each other: they are different forms of the same thing.

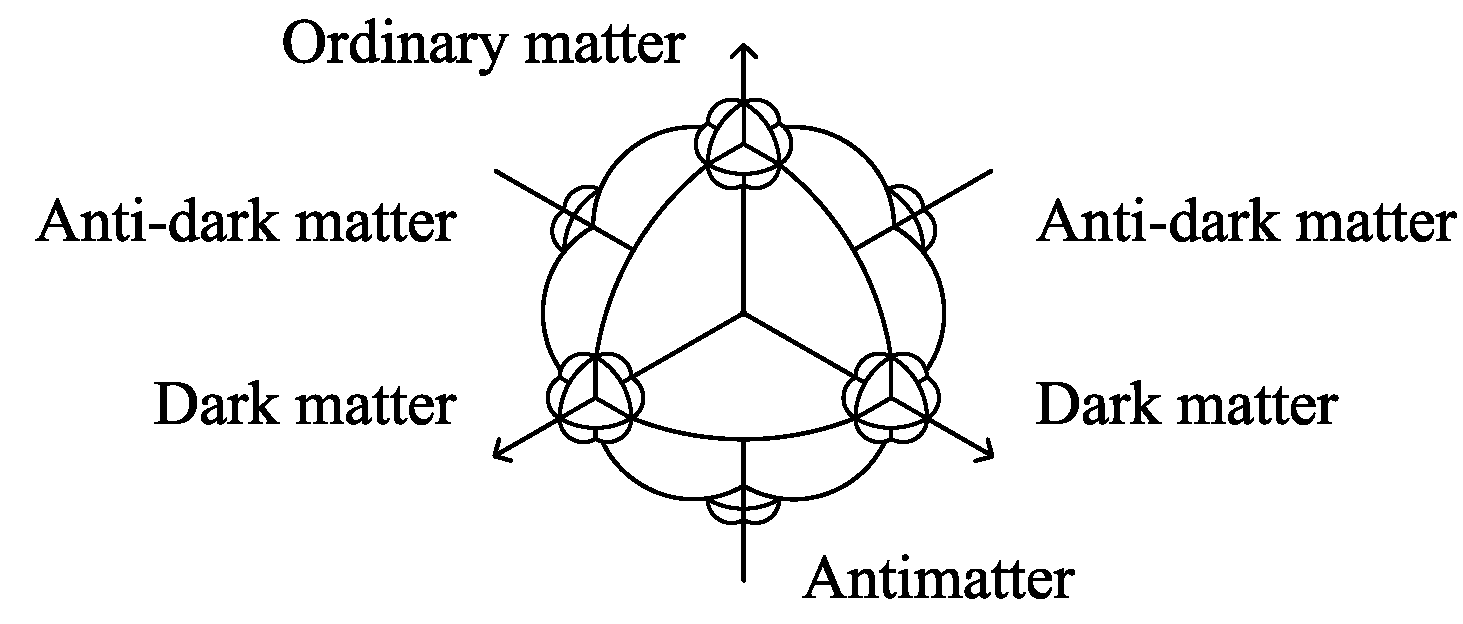

Since there are only three values of quark color, space has only three dimensions. Therefore, space curves in six different directions of these three dimensions, creating six types of matter: ordinary matter, antimatter, two types of dark matter, and two types of anti-dark matter.

Matter and antimatter in opposite directions attract and annihilate each other, while matter and dark matter perpendicular to each other in another dimension have no electromagnetic force. Both matter, antimatter, dark matter, and anti-dark matter are affected by gravitation.

During the Big Bang, matter and antimatter moved in opposite directions, so antimatter ended up on the other side of the universe. Currently, there is only dark matter and anti-dark matter in the observable universe. Particle collision experiments [

16] prove that ordinary matter can be converted into antimatter: they are different forms of the same thing.

Figure 7.

Six types of matter.

Figure 7.

Six types of matter.

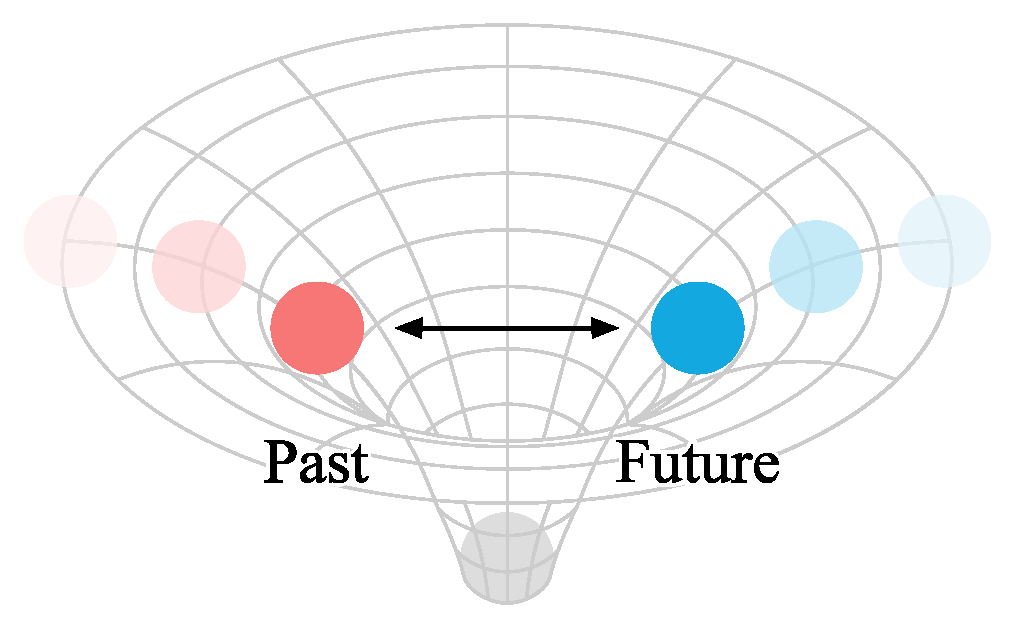

Matter is converted from curved space, and it also curves time. In the double-slit experiment, an interference pattern emerges as the particles build up one by one [

17]. This occurs because matter curves time, causing the particle from the past to interfere with the particle from the future.

In which-way experiment, if particle detectors are positioned at the slits, showing through which slit a photon goes, the interference pattern will disappear [

18]. The mass of the observer is much greater than the particle, and when the observation occurs, the time of the observer engulfs the time of the particle, similar to how a black hole swallows a star, resulting in wave function collapse.

The Wheeler’s delayed choice experiment demonstrates that extracting “which path” information after a particle passes through the slits can appear to retroactively alter its previous behavior at the slits [

19]. Because matter curves time, the particle from the future can interfere with the particle from the past, meaning that the present behavior can have an impact on the past.

The quantum eraser experiment further shows that wave behavior can be restored by erasing or making permanently unavailable the “which path” information [

20]. Since the time of the particle has no connection with the time of the observer, no wave function collapse occurs.

Figure 8.

Matter curves time.

Figure 8.

Matter curves time.

Every elementary particle is matter, and they are all converted from curved space, which gives them rest mass. However, the current commonly accepted physical theories imply or assume that the photon is strictly massless [

22]. The Lorentz factor

is defined as [

23]:

In Newton’s law of universal gravitation, the gravitational acceleration is:

In Einstein’s theory of relativity, the stress-energy tensor

for a non-interacting particle with rest mass

and trajectory

is given by [

2,

3]:

If the photon has no rest mass, it would not be subject to gravitation and could escape from a black hole, contradicting observations [

9].

Of course, there is no doubt that the Standard Model is accurate, so the blame is on the photon. The mistake, therefore, lies with the photon, which should behave precisely as predicted by scientists. The photon is both a wave and a particle, both matter and antimatter, and both has and does not have rest mass.

By the way, the Standard Model also defines the rest mass of the neutrino as zero. Unfortunately, experimental observations by the Super-Kamiokande Observatory and the Sudbury Neutrino Observatories have shown that the neutrino actually has a non-zero rest mass [

13,

14,

15], revealing the limitations of the Standard Model.

3. Gravitation of Hollow Sphere Space

Since there are only three values for the color charge of quarks, so the space has only three dimensions. Therefore, the space released by matter takes the form of a three-dimensional sphere. As this space flows outward, it forms a hollow sphere, and its volume can be written in the following form:

where

is the space released by the matter,

is the radius of the sphere, and

is the degree of space curvature. The greater the degree of space curvature, the greater the gravitational acceleration of the object, which can be expressed as:

When the outward flow of space occurs, its volume remains constant, allowing for the direct calculation of the gravitational acceleration

at a different distance using the gravitational acceleration

at a known distance. The equation can be rewritten to:

The mass of the Earth is approximately

, and the average distance from its center to its surface is about

[

24,

25]. According to Newton’s law of universal gravitation, the value of the gravitational constant is approximately

[

26]. The gravitational acceleration

at the Earth’s surface can be calculated using this law and is given by:

If the distance up to

, the gravitational acceleration

is:

When the gravitational acceleration

of the hollow sphere space is equal to the Newtonian gravitational acceleration

at

, the gravitational acceleration

of the hollow sphere space at

is:

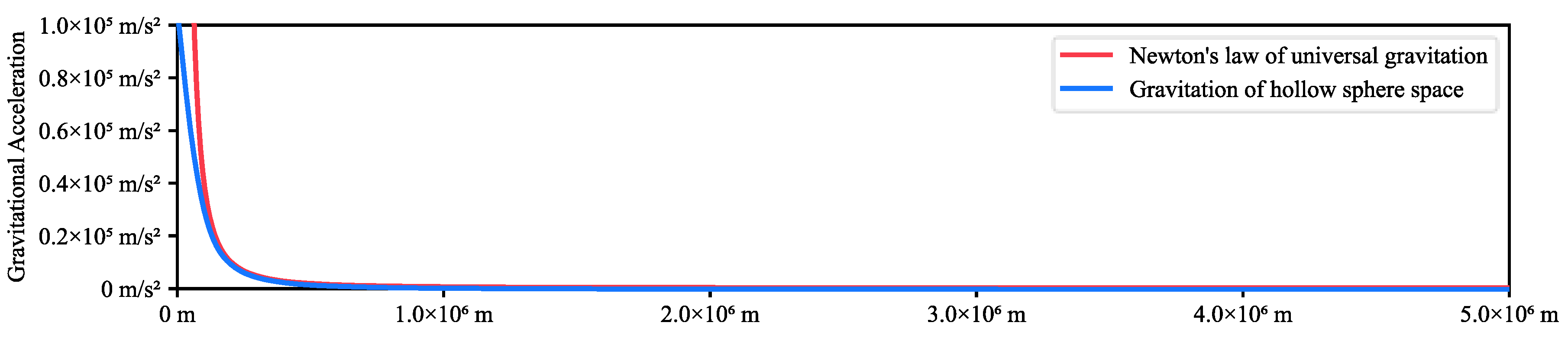

As you can see, the value of the gravitational acceleration calculated using the gravitation of the hollow sphere space is extremely close to the value calculated using Newton’s law of universal gravitation. This confirms that the gravitation of hollow sphere space can be used to accurately calculate the gravitational acceleration. However, when the distance is very large, it is advisable to use professional software to calculate the cube root, as calculators may return zero or negative values. The gravitational acceleration of the Earth at different distances in both models is shown in the following table:

Table 1.

Gravitational acceleration of Earth.

Table 1.

Gravitational acceleration of Earth.

| Distance of Earth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Newton’s law of universal gravitation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gravitation of hollow sphere space |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the distance is zero, Newton’s gravitational acceleration becomes infinite, which is obviously incorrect. In contrast, the gravitation of hollow sphere space is more accurate and does not require the use of Newton’s constant of gravitation. The Schwarzschild radius is a physical parameter that appears in the Schwarzschild solution to Einstein’s field equations [

5,

8]. It corresponds to the radius defining the event horizon of a black hole and can be expressed as:

The Schwarzschild radius of Earth is approximately . However, when the distance is , the Newton’s gravitational acceleration exceeds approximately , it is greater than the speed of light in vacuum, approximately , and this leads to the formation of a black hole, which is obviously wrong.

The mass of the Moon is approximately

, its mean radius is about

, and the time-averaged distance between the centers of the Earth and Moon is about

[

27,

28,

29]. When considering different distances, the gravitational acceleration of the Moon in two different models is shown in the following table:

Table 2.

Gravitational acceleration of Moon.

Table 2.

Gravitational acceleration of Moon.

| Distance of Moon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Newton’s law of universal gravitation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gravitation of hollow sphere space |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The mass of the Sun is approximately

, with a mean radius of about

, and the mean distance between the centers of the Earth and the Sun is about

[

30,

31]. The table below shows the gravitational acceleration of the Sun in two different models at varying distances:

Table 3.

Gravitational acceleration of Sun.

Table 3.

Gravitational acceleration of Sun.

| Distance of Sun |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Newton’s law of universal gravitation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gravitation of hollow sphere space |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expanding the formula, the gravitational acceleration of the hollow sphere space can be derived as:

Then introduce a new variable

to represent

. The equation can be simplified to:

The expression implies that

can approach

as closely as desired by increasing the distance

to infinity. At the surface of the Earth, the ratio of the gravitational acceleration

to the distance

is approximately 0.00000153, which is negligible and can be omitted. The formula can be rewritten as:

Since the accelerations of the two formulas are equal at long distances, the formula can be simplified to:

After removing the same parameters, the gravitation of hollow sphere space

thus takes the form:

The result demonstrates that the space released by matter per kilogram is precisely equal to , providing evidence that matter is converted from curved space, indicating that they are different forms of the same thing. In comparison to Newton’s law of universal gravitation, the gravitation of hollow sphere space has only one more variable, , which is extremely close to at long distances.

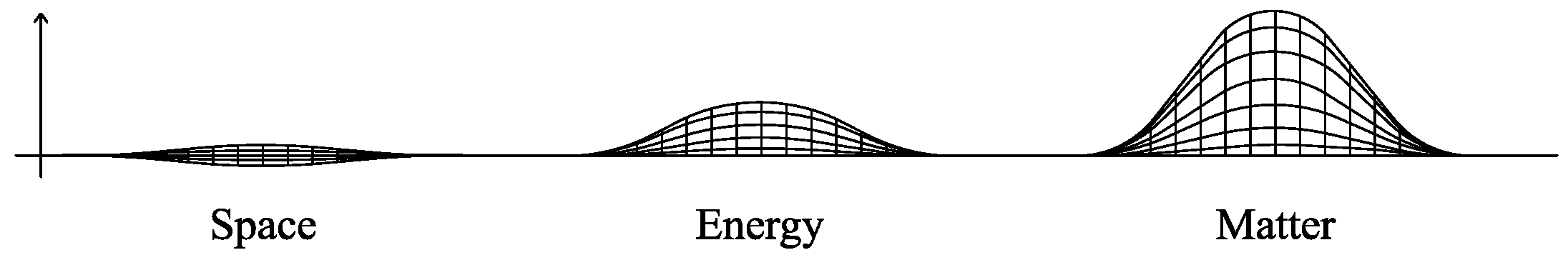

Figure 9.

Gravitational acceleration of Earth.

Figure 9.

Gravitational acceleration of Earth.

The further the distance between the objects, the closer the values of the formulas. In Einstein’s theory of relativity, matter curves spacetime, and the Einstein field equations can be expressed in the following form:

where

is the Einstein tensor,

is the stress-energy tensor,

is the speed of light in vacuum, and

is the Einstein constant of gravitation. In the geometrized unit system, the value of

is set equal to unity. Therefore, it is possible to remove the Newton’s constant of gravitation from the equations to avoid mistakes, especially since the Newton’s law of universal gravitation does not apply to black holes. The equation can be rewritten as:

Since the theory is that matter and energy are both converted from curved space, the form should also be reversed. As space

is proportional to mass

and the fourth power of the speed of light in vacuum

, the equivalent equation for space

can be expressed as:

Of course, under ordinary circumstances, if the Newton’s “constant” of gravitation doesn’t change too much, it can still be used to calculate the gravitational acceleration, the form can be rewritten to:

On the surface of Earth, the gravitational acceleration is:

And the relative error is:

As you can see, this value is still extremely close to the original. What’s more, this formula does not introduce any new variables. Although this formula solves the problem at short distances, when the distance becomes too large, the software calculator may return zero or a negative value, which can be frustrating, so the author has made improvements to the original equation.

In 1665, Isaac Newton extended the binomial theorem to include real exponents, expanding the finite sum into an infinite series. To achieve this, he needed to give binomial coefficients a definition with an arbitrary upper index, which could not be accomplished through the traditional factorial formula. Nonetheless, for any given number

, it is possible to define the coefficients as:

The Pochhammer symbol

is used to represent a falling factorial, which is defined as a polynomial:

This formula holds true for the usual definitions when

is a nonnegative integer. For any complex number

and real numbers

and

with

, the following equation holds:

The series for the cube root can be obtained by setting

, which gives:

At long distances where

, the equation becomes:

At short distances where

, the form of the equation is different:

Certainly, if you prefer String Theory, you can interpret the formula as describing the propagation of gravitons in three-dimensional space, extending as a hollow sphere, with the number of particles remaining constant, and the density decreasing with distance, causing changes in gravitation.