Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was declared a public health emergency of international concern and increased the need for immediate strategies to control infectious diseases and preserve life. The high prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities in older people required attention in different contexts and countries1. In Brazil, the life expectancy for people aged 65 years reduced by 0.9 years in 2020, similar to observed in 20122.

The COVID-19 spread was worrying in long-term care facilities (LTCF), mainly because of the fragility of older people and the collective housing context composed of a staff with potential risk of exposition3. Comas-Herrera et al.1 investigated information from 22 countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, America, and Oceania and verified that LTCF residents accounted for 41% of all deaths from COVID-19, reinforcing the need to support these institutions and protect older people. Moreover, COVID-19 transmission reached 60% in LTCF and increased the rate of death of this population3. Based on recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the Brazilian Ministry of Health and Social Development published technical notes reinforcing urgent measures to prevent and control the COVID-19 in LTCF4.

Recent data identified 7,029 LTCF in Brazil, mainly in the southeast (60.2%) and south (26.7%) regions, compared with 3,548 LTCF in 20105,6. Long-term care is available through public and private systems. However, Brazilian LTCF have insufficient governmental and financial support for the provision of older people and staff, impairing management and care6. Also, some Brazilian studies indicated scarcity and low methodological quality of data about Brazilian older people residing in LTCF7,8. Da Mata et al.8 also draw attention to the lack of data regarding the impact of the pandemic on LTCF and the extent to which COVID-19 prevention and control measures have reached these institutions in the Brazilian context. Official information about rates in LTCF is not yet available in Brazil.

Data regarding rates of infection, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19 and preventive measures from Brazilian LTCF are essential to identify possibilities and barriers to fighting against this pandemic. These data could also contribute to resolute and focused actions to overcome the main obstacles in the daily living of LTCF, even with lack of resource9. Thus, this study aimed to describe rates of infection, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19 among older people and staff of LTCF in a state of Southeastern Brazil identify strategies used to prevent and control this disease and to explore the relationship between the epidemiological data presented and the nature (philanthropic and private) and the size of the LTCF.

Material and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study with a non-probability sampling composed of LTCF from a state of Southeastern Brazil (Latitude: -19.8157 Longitude: -43.9542).

We identified 1,116 LTCF in this state (distributed in 10 regions), mainly in the central region (38.4%), according to data from the Public Ministry of this state, the State Secretariat for Social Development, and the National Front for the Strengthening of LTCF. Of those identified, 911 had a telephone number or e-mail and were invited to participate in the study. To ensure a high response rate, all institutions were invited to participate via e-mail. Then, we contacted institutions three times via telephone. After three unsuccessful attempts, a new round of e-mails was performed. Invitations were also published on websites and social networks of the Public Ministry and the National Front for the Strengthening of LTCF.

Authors elaborated a self-applicable electronic questionnaire (Google Forms) based on recommendations and technical notes from the Federal Government about the context of LTCF and applied to technicians, managers, owners, and professionals working with assistance and administration of these facilities between January 4th and July 1st, 2021. The questionnaire included 55 items, divided into three sections: 1) identification and characterization of the institution and respondent; 2) prevalence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalization, and deaths in older people and staff; and 3) preventive measures adopted to fight against COVID-19, including organizational measures adopted by institutions, infrastructure of institutions, availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) and hygiene items, and training of employees. To ensure the accuracy of information collected on the number of cases of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations or deaths, respondents should only consider those cases confirmed by RT-PCR or serological tests.

Data were transferred to a Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet (Excel®, Redmond, WA, USA), version 10.0, and analyzed using the SPSS software (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA), version 21.0. Data on the characterization of participants, prevalence of cases, hospitalizations and deaths as well as the main preventive measures were presented as absolute and relative frequency. To assess the association between the nature of LTCF (philanthropic and private) and the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths in older people and staff, Sperman's correlation was used. The association between the size of LTCF (considering the number of older people residents) and the number of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths in older people and staff was evaluated by Pearson's correlation. The study followed the Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the research ethics committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (no. 4,427,965/2020). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved in the study.

Results

A total of 164 LTCF (6,017 older people) participated in the study, indicating a response rate of 18%. However, we achieved a good representation of the population when observing the proportion of LTCF in this state according to geographical distribution by planning region (

Table 1). From these LTCF, 120 were philanthropic (72.2%) and 44 were private (27.8%).

The number of available vacancies was 7,108, indicating an occupancy rate of 84.6% during the study. In addition, 37.2% (n = 61) of LTCF were from the central region of this state.

Results were divided into two sections: 1) prevalence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among older people and staff and its association with the size and the nature of institutions of LTCF of LTCF and 2) preventive measures adopted by LTCF to fight the pandemic.

3.1. Prevalence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among older people and staff and its association with the size and the nature of institutions of LTCF

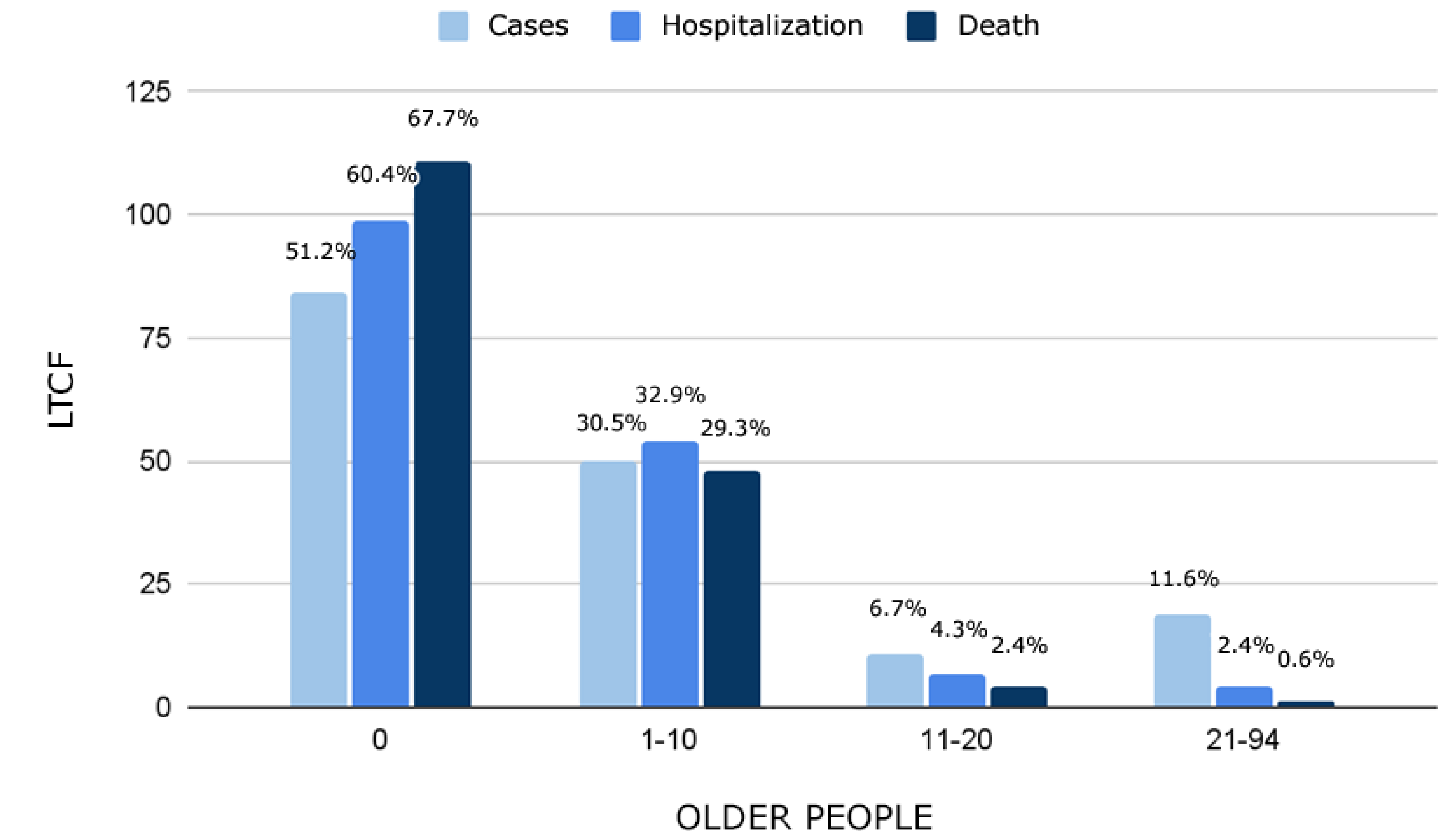

A total of 48.7% (n = 80) of LTCF had older people infected by COVID-19. Among 6,017 older people in LTCF, 1,139 were infected, indicating a COVID-19 prevalence of 18.9%. Older people were hospitalized in 39.6% (n = 65) of LTCF, and hospitalization rate was 34.8% among those with COVID-19 infection. In total, 214 older people from 32.3% (n = 53) of the studied LTCF died from COVID-19, indicating a lethality rate (death of infected people) of 18.8%. The mortality rate (death of the population) from COVID-19 among older people in LTCF was 3.6%. The rate of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths from COVID-19 among participants are shown in

Figure 1.

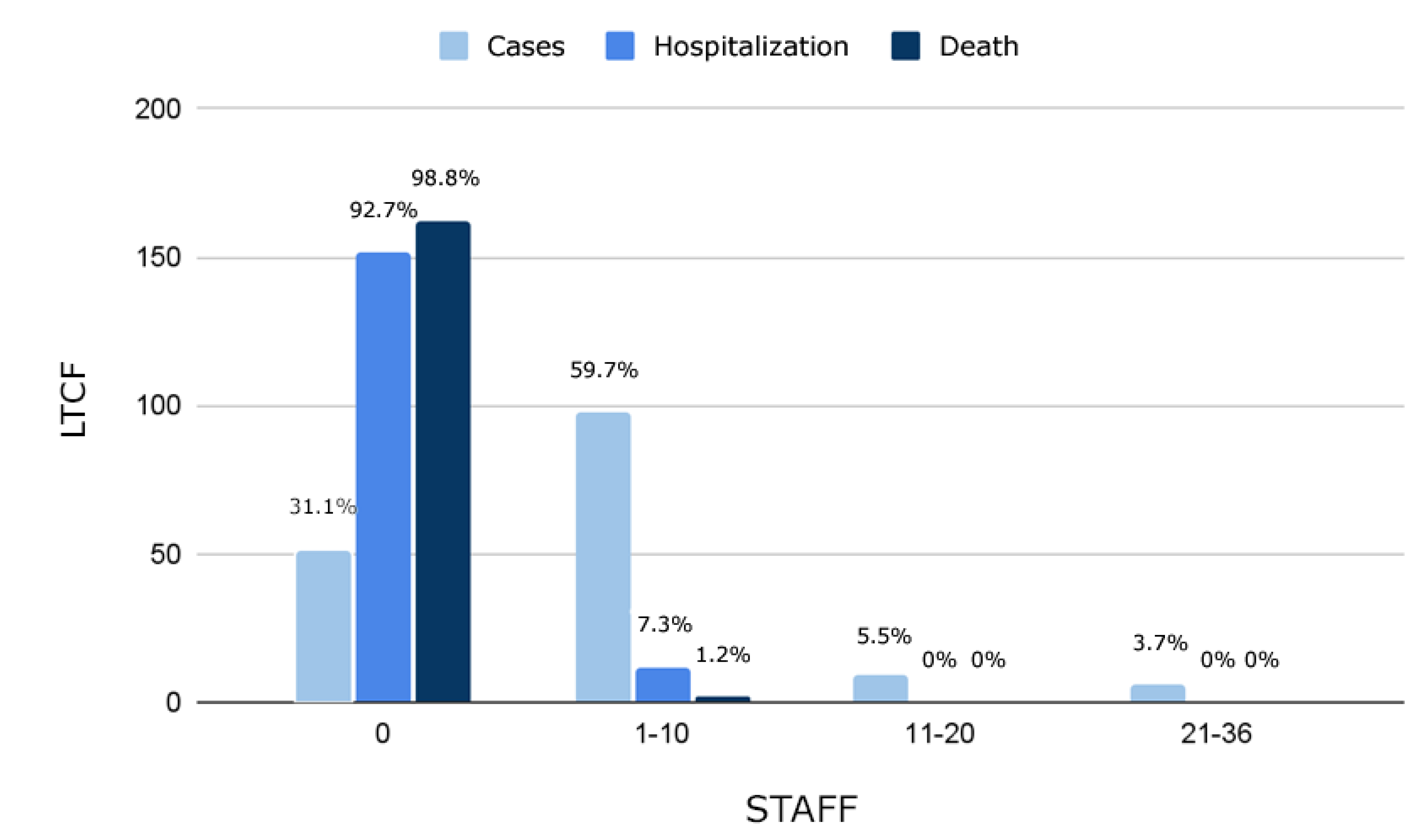

From the studied LTCF, 68.9% (n = 113) had COVID-19 cases among the staff, totaling 664 infected people. The staff was hospitalized in 7.3% of LTCF (n = 12), and hospitalization rate was 2.6% among those with COVID-19 infection. Death among staff workers was reported in 1.2% (n = 2) of LTCF, indicating a 0.3% lethality rate. The rate of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths from COVID-19 among the staff of LTCF are shown in

Figure 2.

There was no significant association between the nature of LTCF and the number of cases (p=0.79), hospitalizations (p=0.38) and deaths (p=0.625) of older people or between the number of cases (p=0 .06), hospitalizations (p=0.88) and deaths (p=0.39) of staff. However, it was possible to observe a significant but weak correlation between the size of the LTCF and the number of cases (r=0.301; p=0.00), hospitalizations (r=0.231; p=0.01) and deaths (r=0.242; p=0.01) of older people and the number of cases (r=0.264; p=0.01), hospitalizations (r=0.064; p=0.04) and deaths (r=0.154; p= 0.04) of the staff.

3.2. Preventive measures adopted by LTCF to fight the pandemic

Preventive measures were divided into organizational, infrastructure, hygiene items and PPE, and staff training against COVID-19.

3.2.1. Organizational measures

A total of 96.9% (n = 159) of managers from LTCF claimed an action plan to prevent and control the COVID-19. However, almost 25% (n = 37) of LTCF did not have a contingency plan with the municipal health authorities to manage older people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection.

Most LTCF (98.2%, n = 161) increased the frequency of cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and furniture, and 1.8% (n = 3) reported that adequate cleaning and disinfection were not possible. In addition, 97% (n = 159) of LTCF reported cleaning or quarantine procedures for packaging food, vegetables, and fruits.

As a measure of disease control, 82.3% (n = 135) of LTCF offered COVID-19 testing for all staff and older people at least once. Active screening of signs and symptoms of COVID-19 was also conducted in professionals and providers who accessed 92.1% (n = 151) of LTCF.

Visits from family members and friends were suspended in 95.7% (n = 157) of LTCF, and 89.6% (n = 147) also suspended collective socialization activities among older people.

Most LTCF (84.8%, n = 139) performed in-person medical consultations for suspected cases of COVID-19, and 94.5% reported positive cases to the Epidemiological Surveillance of the Brazilian Unified Health System, the Public Ministry, Social Assistance Secretariat, Elderly Rights Council, and other authorities.

Some older people from 4.3% (n = 7) of LTCF were not registered in the reference Basic Health Unit and presented an outdated vaccination schedule according to recommendations of the National Immunization Program.

3.2.2. Infrastructure measures

A total of 59.1% (n = 67) and 55.5% (n = 73) of LTCF did not use collective living spaces and drinking fountains, respectively; all LTCF maintained the highest ventilation flow in environments.

A specific entrance area for professionals, staff, and providers was available in 78.7% (n =129) of LTCF. Most (85.4%, n = 140) had a place to isolate suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19; however, 17.3% (n = 24) of these isolation places did not have a bathroom.

3.2.3. Hygiene items and PPE

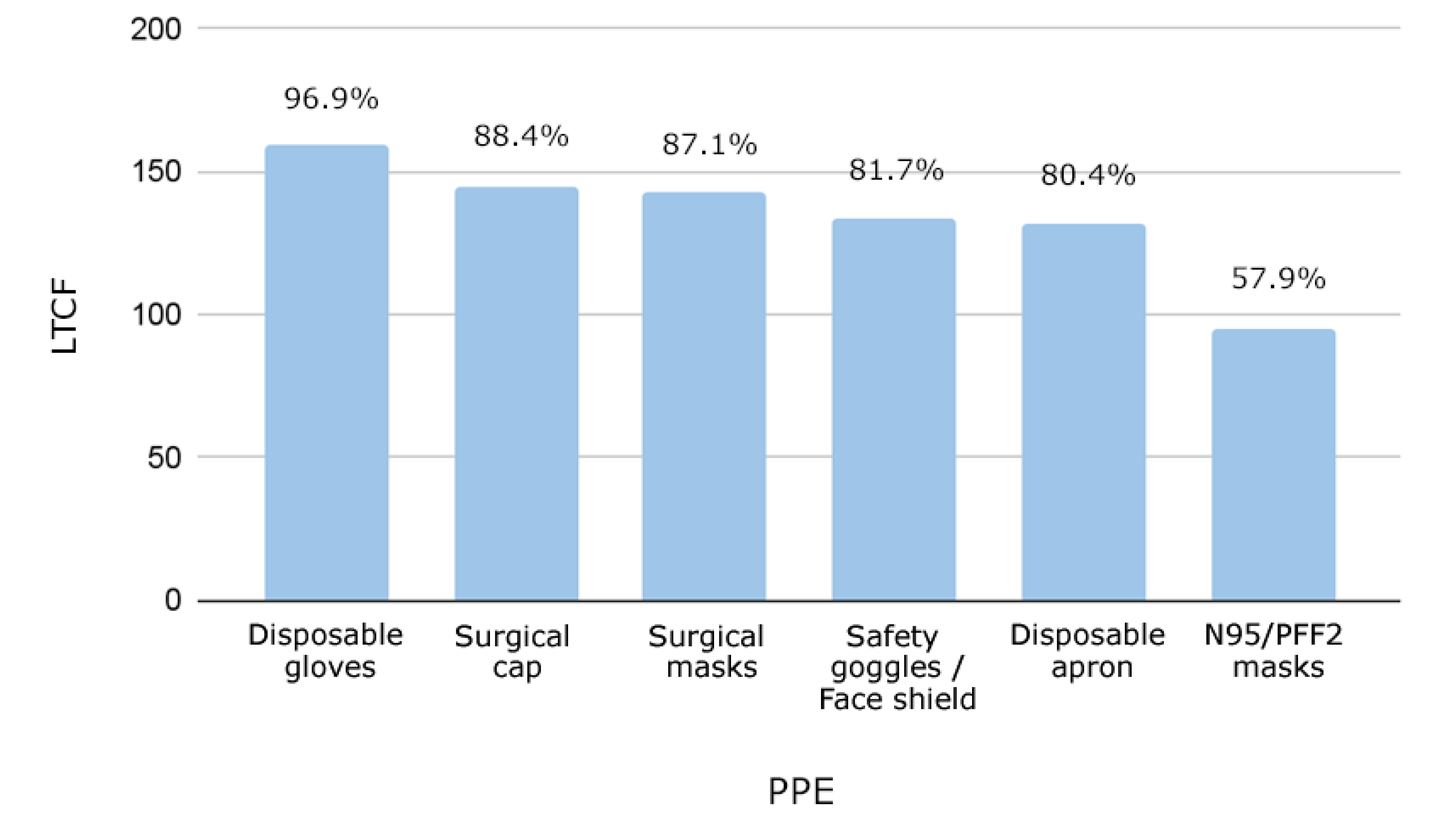

Not all participating institutions had all the recommended PPE to protect against COVID-19 (i.e., surgical, N95/PFF2, and fabric masks; disposable gloves; disposable apron; boots; shoe covers; face shield; safety goggles; and surgical cap). Several LTCF managers reported lack of PPE for routine needs, such as N95/PFF2 masks (42%, n = 69) and safety goggles (44.5%, n = 73) (

Figure 3).

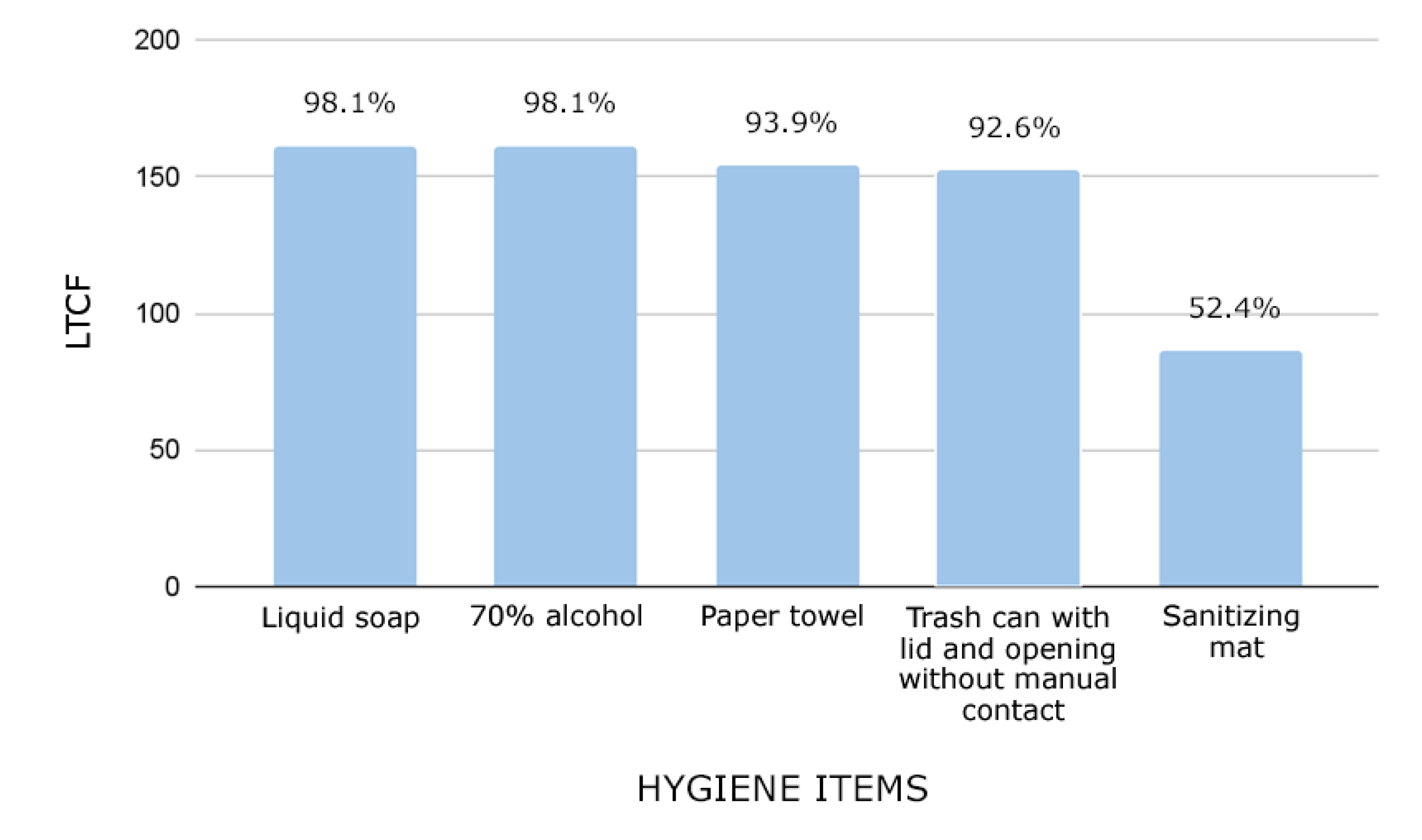

Over 150 LTCF (96.9%) had disposable gloves, and 100 (57.9%) had N95/PFF2 masks. Moreover, 98% (n = 161) of LTCF provided 70% alcohol for hand hygiene of older people, and 99.4% (n = 163) for the staff. The availability of other hygiene items is shown in

Figure 4.

From the studied LTCF, 79.9% (n = 131) received guidance to manage suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases. Most professionals (97%, n = 159) trained hand hygiene techniques, proper use of PPE, and maintenance of social distancing. Moreover, training of LTCF was performed monthly (61%, n = 100), fortnightly (7.3%, n = 12), weekly (18.3%, n = 30), or daily (13.4%, n = 22).

LTCF provided posters, booklets, and verbal guidance about the correct techniques to older people, the importance of frequent hand hygiene (94.5%), respiratory etiquette (96.3%), and help of the staff with difficulties to perform hand hygiene (98.2%). Professionals, providers, and people from delivery services were instructed regarding hand hygiene with soap and water or alcohol before entering all LTCF.

Discussion

This study presented data regarding rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death of older people and staff of LTCF in a state of Southeastern Brazil and the main preventive measures adopted. Although electronic questionnaires are advantageous, they commonly achieve low response rates from participants. For instance, studies from China10 and Ireland11 showed 48% and 62.2% of LTCF adherence, respectively. In contrast, Kariya et al.12 identified a low response rate (16.9%) of questionnaires regarding infection prevention and control measures among LTCF. Daily problems among older people and staff during the pandemic may have also contributed to the low availability of participants10,11. Furthermore, cut-off points for response rates are not recommended in rapidly developing scenarios, such as the one experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, since studies with small samples may also contain important findings to direct further research13.

A high variability of COVID-19 cases was observed among older people in LTCF worldwide (4% to 77%, mean prevalence of 37%)14. Wachholz et al.15 1 identified an incidence of 6.57% of COVID-19 cases in 2,154 Brazilian LTCF (n = 59,878 older people). In the present study, 48.8% (n = 80) of LTCF had COVID-19 cases among older people, which is lower than in developed countries1. Research from Ireland (28 LTCF) and Italy (57 LTCF) showed COVID-19 cases in 64.9% and 75% of the sample, respectively11,16 2; 3. Nevertheless, some factors may have influenced our findings, such as a low testing rate and high underreporting rates8.

Older people were hospitalized due to COVID-19 in 34.8% of the studied LTCF, reinforcing the fragility of this population. During the study, the hospitalization rate due to COVID-19 was almost four-fold higher (34.8%) for older people in LTCF than for the general population (8.8%) from state17.

The present study reported a lower lethality rate of COVID-19 in LTCF of a state of Brazil than in Ireland (27.6%), Australia (33.1%) and Canada (27.8%)11,18,19. At least 40% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States were from older people in LTCF20 4. Wachholz et al.15 showed a mortality and lethality rate of approximately 1.47% and 22.44%, respectively, among older people in LTCF in Brazil due to COVID-19; the mortality rate was 1.15% in this state.

Contamination of the staff is a substantial risk to older people in LTCF3. The high prevalence of COVID-19 among the staff could be explained by the transit in other environments (e.g. hospitals, other facilities, and public transport)3. Although health professionals were asymptomatic14, few LTCF presented hospitalization and death cases, reinforcing the low vulnerability of this public due to a reduced number of risk factors.

The Ministry of Health published the National Contingency Plan for the Care of Institutionalized Older People in the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, which included guidelines for prevention, support, and health recovery of institutionalized older people during the pandemic3,8. Approximately 77.5% of LTCF in this study did not develop this plan with health authorities. In contrast, 96.9% of LTCF had an internal institutional plan that considered individualities.

In-person visits by the socio-family network and collective activities occurred in some LTCF, exposing older people to risk since social distancing is essential to control Sars-Cov-2 transmission3. In this context, the Ministry of Health recommended suspending in-person visits to LTCF to avoid contact and reduce disease transmission between older people and infected people4.

Active screening (i.e., monitoring of signs and symptoms of COVID-19 in older people, professionals, and visitors) allows early detection and isolation of suspected and confirmed cases in LTCF and is essential for an effective control of COVID-1921. Most LTCF offered testing for all older people and staff at least once during the pandemic. Immediate notification to epidemiological surveillance bodies is also needed in suspected cases (i.e., symptoms of influenza or severe acute respiratory syndrome) to improve protection measures and perform adequate strategies against the virus4. In the present study, LTCF notified COVID-19 cases to the Epidemiological Surveillance of SUS, contributing to monitoring of virus transmission and health situation of this population.

According to the Ministry of Health, LCF are also responsible for training professionals to prevent and control COVID-19 transmission3. Most staff from LTCF (97%) received training only to prevent COVID-19 transmission, including the correct and safe use of PPE. Furthermore, most training actions were conducted online in Brazil, especially by the organized civil society22. Nevertheless, considering that most populations have low socioeconomic and educational levels, dissemination of this information may have been insufficient7. Older people in LTCF present different dependence levels, which may also impair self-care and the use of preventive measures against COVID-1923. Almost half of LTCF from the present study used collective drinking fountains, and 40.8% used living spaces with shared objects. Most LTCF guided the correct hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, preventing the virus spread and contamination of older people. Most LTCF increased the daily cleaning routine and disinfection of surfaces and furniture. However, most LTCF did not have a specific entrance area for professionals and employees, increasing the risk of contact with the living area of older people. Although most managers of LTCF (85.4%) reported having isolated places for suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19, 17.3% did not have a bathroom in this place. The lack of infrastructure observed in LTCF impairs COVID-19 prevention8 and highlights the need for infrastructure strategies to protect older people in possible situations of viral contamination.

Dykgraaf et al.24 identified the following potential strategies to prevent or mitigate COVID-19 transmission in LTCF: serial testing of older people and staff; staff confinement with residents in LTCF; digital and telehealth training; restriction of visits; environmental ventilation; intersectoral collaboration; and staff training. In contrast, routine temperature measurement without other diagnostic tools, symptom-based testing, or tracking the prevalence after case identification were possibly ineffective24. Authors also reinforced that preventive measures should be offered for most vulnerable people24, even with a worldwide vaccination program prioritizing older people in LTCF. The findings of Dykgraaf et al.24 were reinforced by a review published25, suggesting that non-pharmacological measures implemented in LTCF could prevent COVID-19 infection and its consequences.

The studied LTCF showed a lack of PPE, such as N95/PFF2 masks and goggles. A Chinese study conducted with 484 LTCF showed a lack of PPE in 72% of the sample10. These findings corroborated studies from the other locations7,26. These results may reflect the ineffectiveness of public policies for LTCF from several countries27. Thus, efforts are needed to acquire PPE for the LTCF staff since they can be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-1914.

Authors from several countries also highlighted these challenges. Wachholz et al.9 analyzed information from 23 managers of LTCF in Hispanic American countries during the COVID-19 pandemic and showed obstacles similar to those found in our study (e.g., difficulty to develop a strategic plan to manage cases and deaths, acquire PPE, and test for SARS-Cov-2). Therefore, these multiple needs require a coordinated response between managers and the government. Based on the present data, the scenario experienced in LTCF from this place at the beginning of the pandemic was better than LTCF worldwide, especially concerning COVID-19 lethality among older people1. The civil society was mobilized even without an effective public policy to protect LTCF22, which possibly helped minimize the negative impacts of COVID-19 (i.e., number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths). This mobilization began with the “screaming for LTCF – Urgent – COVID-19” 28, which led to a public hearing in the National Congress on April 7, 2020. Because of this, the National Front for the Strengthening of LTCF united hundreds of professionals and volunteers across Brazil to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on LTCF29. Authors from the field of aging and public management also proposed policies (e.g., CIAT: coordination, identification, assessment, and work) to support government actions against the pandemic and manage the impacts of COVID-19 effects in LTCF of developing countries30.

Vaccines against COVID-19 were not available in Brazil at the time of elaboration of the questionnaire for the present study. We also highlight that rates of infection, hospitalization, and death observed among older people and staff may have been impacted vaccination, which coincided with the data collection period. Nevertheless, this study is not free of limitations. The growing demand for research on this topic, lack of time due to workload, and cultural habits may have contributed to a lower response rate than international studies10,11, more than any systematic reason as exhaustive methodological procedures have been adopted to try to reach the public in question. The number of people working in LTCF was not collected, which hindered the determination of COVID-19 prevalence and mortality rate among the staff. Furthermore, as it was a questionnaire answered by those responsible for the LTCF, there is no way to guarantee the accuracy of the information on the epidemiological data nor the extent to which preventive measures were in place. Finally, it was not the aim of this study to explore whether and how the preventive measures adopted by LTCF were associated with epidemiological data. As the data were collected in different periods of the pandemic (Jan-Jul/2021), with some institutions answering the questionnaire during the outbreak period and others in moments of relative calm, it was not possible to control whether the preventive measures had been intensified or made more flexible as a result.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 widely affected LTCF, highlighting the need for civil and governmental actions due to the vulnerability of older people. We showed a COVID-19 prevalence in older people and staff from LTCF of a state of Brazil. Moreover, COVID-19 lethality was higher in older people than in the staff. The nature of the LTCF was not associated with the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths, but the number of elderly people living in the same LTCF was. Prevention strategies, especially infrastructure measures and availability of PPE, could prevent the contamination of older people and the staff; however, many LTCF could not adopt some of these recommendations.

Barriers to fighting against COVID-19 were also identified in LTCF, justifying the need for actions focused on daily obstacles and encouragement of public policies. The results emphasize the continuity and improvement of actions to protect older people and promote health education with managers, professionals, and residents of LTCF. Further studies are needed to monitor the impacts and challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- Comas-Herrera A, Zalakaín J, Lemmon E, Henderson D, Litwin C, Hsu A, Schmidt A, Arling G, Kruse F, Fernández JL. Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: international evidence. [Cited 2021 Mar 20]. Available from: https:// LTCCovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-Covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence.

- Castro MC, Gurzenda S, Turra CM, Kim S, Andrasfay T, Goldman N. Reduction in life expectancy in Brazil after COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 1629–1635.

- Moraes EN, Viana LG, Resende LMH, Vasconcellos LS, Moura AS, Menezes A, Mansano NH, Rabelo R. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities for the elderly: laboratory screening and disease dissemination prevention strategies. Cien Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 3445–3458. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. COVID-19: Plano Nacional apresenta medidas de cuidado à saúde de pessoas idosas institucionalizadas. [cited 2021 Dec 13]. Available from: https://aps.saude.gov.br/noticia/8196.

- Lacerda T, Neves A, Buarque G, Freitas D, Tessarolo M, González N, Barbieri S, Camarano A, Giacomin K, Villas-Boas P. Geospatial panorama of long-term care facilities in Brazil: a portrait of territorial inequalities. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Camarano A, Kanso S. As instituições de longa permanência para idosos no Brasil. Rev Bras Estud Popul. 2010, 27, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wachholz PA, De Oliveira DC, Hinsliff-Smith K, Devi R, Villas Boas PJF, Shepherd V, Jacinto AF, Watanabe HAW, Gordon AL, Ricci NA. Mapping Research Conducted on Long-Term Care Facilities for Older People in Brazil: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mata F, Oliveira D. COVID-19 and Long-Term Care in Brazil: Impact, Measures and Lessons Learned. International Long Term Care Policy Network. [Cited 2022 Mar 20]. Available from: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-Long-term-care-situation-in-Brazil-6-May-2020. /.

- Wachholz P, Jacinto A, Melo R, Dinamarca-Montecinos J, Villas-Boas P. COVID-19: challenges in long-term care facilities for older adults in Hispanic American countries. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2020, 14, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi M, Zhang F, He X, Huang S, Zhang M, Hu X. Are preventive measures adequate? An evaluation of the implementation of COVID-19 prevention and control measures in nursing homes in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021, 21, e641. [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly, S. P.; Dyer, A. H.; Noonan, C.; Martin, R.; Kennelly, S. M.; Martin, A.; O'Neill, D.; Fallon, A. Asymptomatic carriage rates and case fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents and staff in Irish nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2021, 50, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariya N, Sakon N, Komano J, Tomono K, Iso H. Current prevention and control of health care-associated infections in long-term care facilities for the elderly in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2018, 24, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sataloff RT, Vontela S. Response Rates in Survey Research. J Voice. 2021, 35, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gmehlin CG, Munoz-Price LS. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in long-term care facilities: A review of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and containment interventions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020, 43, 504–509.

- Wachholz P, Moreira V, Oliveira D, Watanabe H, Villas-Boas P. Estimates of infection and mortality from covid-19 in care homes for older people in Brazil. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2020, 14, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzoletti L, Zanolin ME, Tocco Tussardi I, Alemayohu MA, Zanetel E, Visentin D, Fabbri L, Giordani M, Ruscitti G, Benetollo PP, Tardivo S, Torri E. Risk Factors Associated with Nursing Home COVID-19 Outbreaks: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, e13175. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico COVID-19. 30 de Julho de 2021. [cited 2021 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/coronavirus/boletins-epidemiologicos.

- Ibrahim JE, Li Y, McKee G, Eren H, Brown C, Aitken G, Pham T. Characteristics of nursing homes associated with COVID-19 outbreaks and mortality among residents in Victoria, Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2021, 40, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown KA, Jones A, Daneman N, Chan AK, Schwartz KL, Garber GE, Costa AP, Stall NM. Association Between Nursing Home Crowding and COVID-19 Infection and Mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med. 2021, 181, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, J. "Abandoned" Nursing Homes Continue to Face Critical Supply and Staff Shortages as COVID-19 Toll Has Mounted. JAMA. 2020, 324, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu F, Zheng C, Wang L, Geng M, Chen H, Zhou S, Ran L, Li Z, Zhang Y, Feng Z, Gao GF, Chang Z. Interpretation of the Protocol for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 in China (Edition 8). China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes D, Taveira R, Silva L, Kusumota L, Giacomin K, Rodrigues R. Performance of social movements and entities in the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: Older adults care in long-term care facilities. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2021, 24, e210048. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DC, Barbu MG, Beiu C, Popa LG, Mihai MM, Berteanu M, Popescu MN. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Long-Term Care Facilities Worldwide: An Overview on International Issues. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, e8870249. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Herrera A, Zalakaín J, Lemmon E, Henderson D, Litwin C, Hsu A, Schmidt A, Arling G, Kruse F, Fernández JL. Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: international evidence. [Cited 2021 Mar 20]. Available from: https://LTCCovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-Covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence.

- Castro MC, Gurzenda S, Turra CM, Kim S, Andrasfay T, Goldman N. Reduction in life expectancy in Brazil after COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 1629–1635.

- Moraes EN, Viana LG, Resende LMH, Vasconcellos LS, Moura AS, Menezes A, Mansano NH, Rabelo R. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities for the elderly: laboratory screening and disease dissemination prevention strategies. Cien Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 3445–3458. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. COVID-19: Plano Nacional apresenta medidas de cuidado à saúde de pessoas idosas institucionalizadas. [cited 2021 Dec 13]. Available from: https://aps.saude.gov.br/noticia/8196.

- Lacerda T, Neves A, Buarque G, Freitas D, Tessarolo M, González N, Barbieri S, Camarano A, Giacomin K, Villas-Boas P. Geospatial panorama of long-term care facilities in Brazil: a portrait of territorial inequalities. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Camarano A, Kanso S. As instituições de longa permanência para idosos no Brasil. Rev Bras Estud Popul. 2010, 27, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wachholz PA, De Oliveira DC, Hinsliff-Smith K, Devi R, Villas Boas PJF, Shepherd V, Jacinto AF, Watanabe HAW, Gordon AL, Ricci NA. Mapping Research Conducted on Long-Term Care Facilities for Older People in Brazil: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mata F, Oliveira D. COVID-19 and Long-Term Care in Brazil: Impact, Measures and Lessons Learned. International Long Term Care Policy Network. [Cited 2022 Mar 20]. Available from: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-Long-term-care-situation-in-Brazil-6-May-2020.

- Wachholz P, Jacinto A, Melo R, Dinamarca-Montecinos J, Villas-Boas P. COVID-19: challenges in long-term care facilities for older adults in Hispanic American countries. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2020, 14, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi M, Zhang F, He X, Huang S, Zhang M, Hu X. Are preventive measures adequate? An evaluation of the implementation of COVID-19 prevention and control measures in nursing homes in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021, 21, e641. [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly, S. P.; Dyer, A. H.; Noonan, C.; Martin, R.; Kennelly, S. M.; Martin, A.; O'Neill, D.; Fallon, A. Asymptomatic carriage rates and case fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents and staff in Irish nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2021, 50, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariya N, Sakon N, Komano J, Tomono K, Iso H. Current prevention and control of health care-associated infections in long-term care facilities for the elderly in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2018, 24, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sataloff RT, Vontela S. Response Rates in Survey Research. J Voice. 2021, 35, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmehlin CG, Munoz-Price LS. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in long-term care facilities: A review of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and containment interventions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020, 43, 504–509.

- Wachholz P, Moreira V, Oliveira D, Watanabe H, Villas-Boas P. Estimates of infection and mortality from covid-19 in care homes for older people in Brazil. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2020, 14, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzoletti L, Zanolin ME, Tocco Tussardi I, Alemayohu MA, Zanetel E, Visentin D, Fabbri L, Giordani M, Ruscitti G, Benetollo PP, Tardivo S, Torri E. Risk Factors Associated with Nursing Home COVID-19 Outbreaks: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, e13175. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico COVID-19. 30 de Julho de 2021. [cited 2021 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/coronavirus/boletins-epidemiologicos.

- Ibrahim JE, Li Y, McKee G, Eren H, Brown C, Aitken G, Pham T. Characteristics of nursing homes associated with COVID-19 outbreaks and mortality among residents in Victoria, Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2021, 40, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown KA, Jones A, Daneman N, Chan AK, Schwartz KL, Garber GE, Costa AP, Stall NM. Association Between Nursing Home Crowding and COVID-19 Infection and Mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med. 2021, 181, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, J. "Abandoned" Nursing Homes Continue to Face Critical Supply and Staff Shortages as COVID-19 Toll Has Mounted. JAMA. 2020, 324, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu F, Zheng C, Wang L, Geng M, Chen H, Zhou S, Ran L, Li Z, Zhang Y, Feng Z, Gao GF, Chang Z. Interpretation of the Protocol for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 in China (Edition 8). China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes D, Taveira R, Silva L, Kusumota L, Giacomin K, Rodrigues R. Performance of social movements and entities in the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: Older adults care in long-term care facilities. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2021, 24, e210048. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DC, Barbu MG, Beiu C, Popa LG, Mihai MM, Berteanu M, Popescu MN. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Long-Term Care Facilities Worldwide: An Overview on International Issues. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, e8870249. [Google Scholar]

- Dykgraaf SH, Matenge S, Desborough J, Sturgiss E, Dut G, Roberts L, McMillan A, Kidd M. Protecting Nursing Homes and Long-Term Care Facilities From COVID-19: A Rapid Review of International Evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021, 22, 1969–1988.

- Stratil JM, Biallas RL, Burns J, Arnold L, Geffert K, Kunzler AM, Monsef I, Stadelmaier J, Wabnitz K, Litwin T, Kreutz C, Boger AH, Lindner S, Verboom B, Voss S, Movsisyan A. Non-pharmacological measures implemented in the setting of long-term care facilities to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections and their consequences: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 15, CD015085. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DM, Greene J. State Actions and Shortages of Personal Protective Equipment and Staff in U.S. Nursing Homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020, 68, 2721–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomin K, Villas-Boas P, Domingues M, Wachholz P. Caring throughout life: peculiarities of long-term care for public policies without ageism. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2021, 15, e0210009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe H, Domingues M, Duarte Y. COVID-19 e as instituições de longa permanência para idosos: cuidado ou morte anunciada? Geriatr Gerontol Aging 2020, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Horta N, Boas P, Carvalho A, Torres S, Campos G, Angioletti A. Brazilian National Front for Strengthening Long-Term Care Facilities for Older People: history and activities. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2021, 15, e0210064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P, Neto J, Duarte M, Frank M, Giacomin K, Villas-Boas P, Saddi F, Wachholz P. An emergency strategy framework for managing COVID-19 in long-term care facilities in Brazil. Geriatr Gerontol Aging. 2021, 15, e0210014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).