2.1. Background

People are forced to flee from their home countries for different reasons. While migrants often move voluntarily to seek a better quality of life through work, education, or to explore new cultures and life journeys, asylum seekers and refugees leave their countries due to conflict, violence, crises and emergencies, persecution and human rights violations, poverty, lack of basic services, food insecurity or disasters, and effects of climate change (IFRC, 2021, 2022). Migration can be voluntary or involuntary, but most of the time a combination of choices and constraints are involved (ICRC, 2015). The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) 1 adopted a broad perspective on migration and identified migrants as “all people who leave or flee their home to seek safety or better prospects abroad, and who may be in distress and need of protection or humanitarian assistance”. Refugees and asylum seekers are included in this description and have specific protection under international law (UNICEF, 2017; 2022). Refugees are people escaping from armed conflicts or persecution (2022). This statute is granted in the host country considering a well-supported fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, politics, or membership of a particular member group (European Union, 2022). Asylum seekers are people who have not yet been recognised as refugees. They apply for international protection for which a definitive decision has not been reached (CVP, 2019). The recognition as an asylum seeker is dependent on the national authorities’ decisions (UNICEF, 2017; 2022). In this process, children and adolescents unaccompanied by a caregiver face particular risk, including being exposed frequently to discrimination, marginalization, institutionalization, and social exclusion (WHO, 2018).

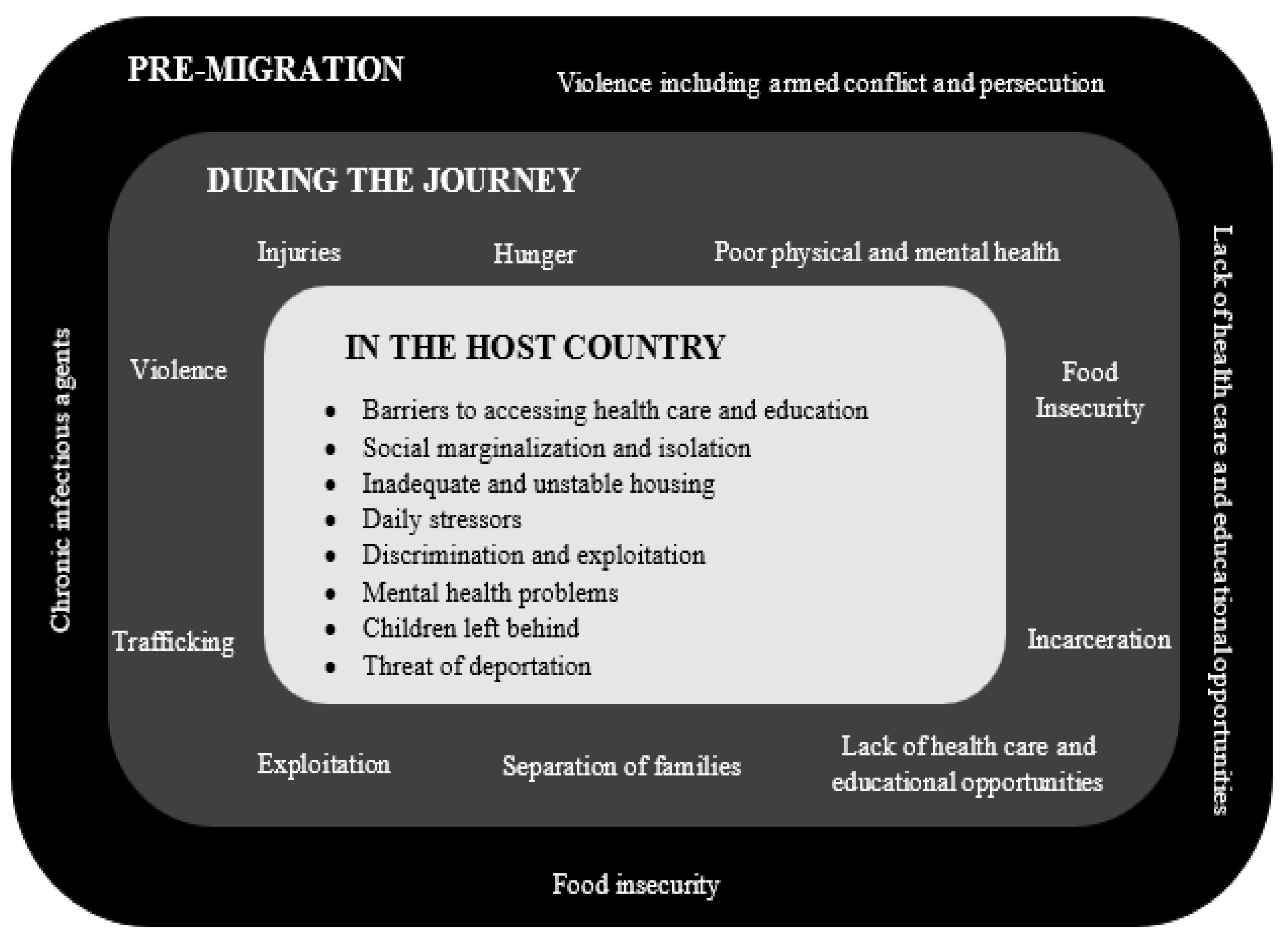

The World Health Organization outlined the unaccompanied minor refugees and asylum seekers’ risk factors for health problems and poor well-being during the different phases of migration (

Figure 1).

Accordingly, we ought to recognize the urgency to find ways to support these two groups in each of the identified phases. During the integration process in the host country, support from central and local authorities, non-governmental institutions, and the general population are key to preventing and mitigating further health and social complications and avoiding cultural/social conflicts in refugees’ life or in the daily operation of local communities. Specific intervention strategies are needed to both, support the integration of refugees and asylum seekers as well as to promote the education and information about the country’s inhabitants towards the demystification of certain recurrent preconceptions of embodied danger, violence, and trauma (Eide et al., 2018; Varvin, 2017; Vervliet et al., 2014) towards the acknowledgment of the importance of including this migrant population for a peaceful and sustainable future.

Portugal is an emigration country. Until the 2015/2016 immigration crises in Europe, most migration in Portugal was family or labor related (ODCE, 2019, p. 11). Migration movements from the Brazil and African Countries of Portuguese Official Language (PALOP) intensified after the end of the Portuguese dictatorship regime and the colonial war (after the year 1974) (Casquilho-Martins & Ferreira, 2022). During the turn of the 20thcentury, migration movements from Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Brazil, United Kingdom, France, and Italy (OCDE, 2019; Pordata, 2023) continued gaining momentum, while a first wave of work migration arriving from the Eastern and Southeastern European Countries (i.e., Ukraine, Romania), China, India and Nepal was identified between the 2000s and the 2010s (Portada, 2023). The 2021 national census refers to an actual number of 542165 foreign citizens living in Portugal, from which 36,9% are from Brazil (n=199,810), 5,8% from Angola (n=31556) and 5,0% from Cape Verde (n=27144).

Regarding the humanitarian protection of refugees and asylum seekers, until 2015, Portugal only granted protection to a small number of individuals, compared with other European countries (OCDE, 2019). However, in 2015, Portugal was one of the EU members states answering affirmatively to the call for their relocation from the Mediterranean coast (e.g., Italy and Greece) where the system has been overloaded since this period (CVP, 2019, 2022; FRA, 2022). In sequence, the number of asylum requests tripled in 2017 (n=1750), whereas between 2000 and 2014 the country only received a constant number of 200 asylum requests per year (OCDE, 2019, p.11). The actual armed conflict in Ukraine generated an unprecedented deployment of Portuguese public authorities, social services and humanitarian aid structures for the reception and integration of displaced Ukrainian citizens (ReferNet Portugal and Cedefop, 2022). Early in 2023, the Foreign and Border Service (SEF) revealed that Portugal has granted 58,043 (14,111 minors) temporary protections to Ukrainian citizens since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine2.

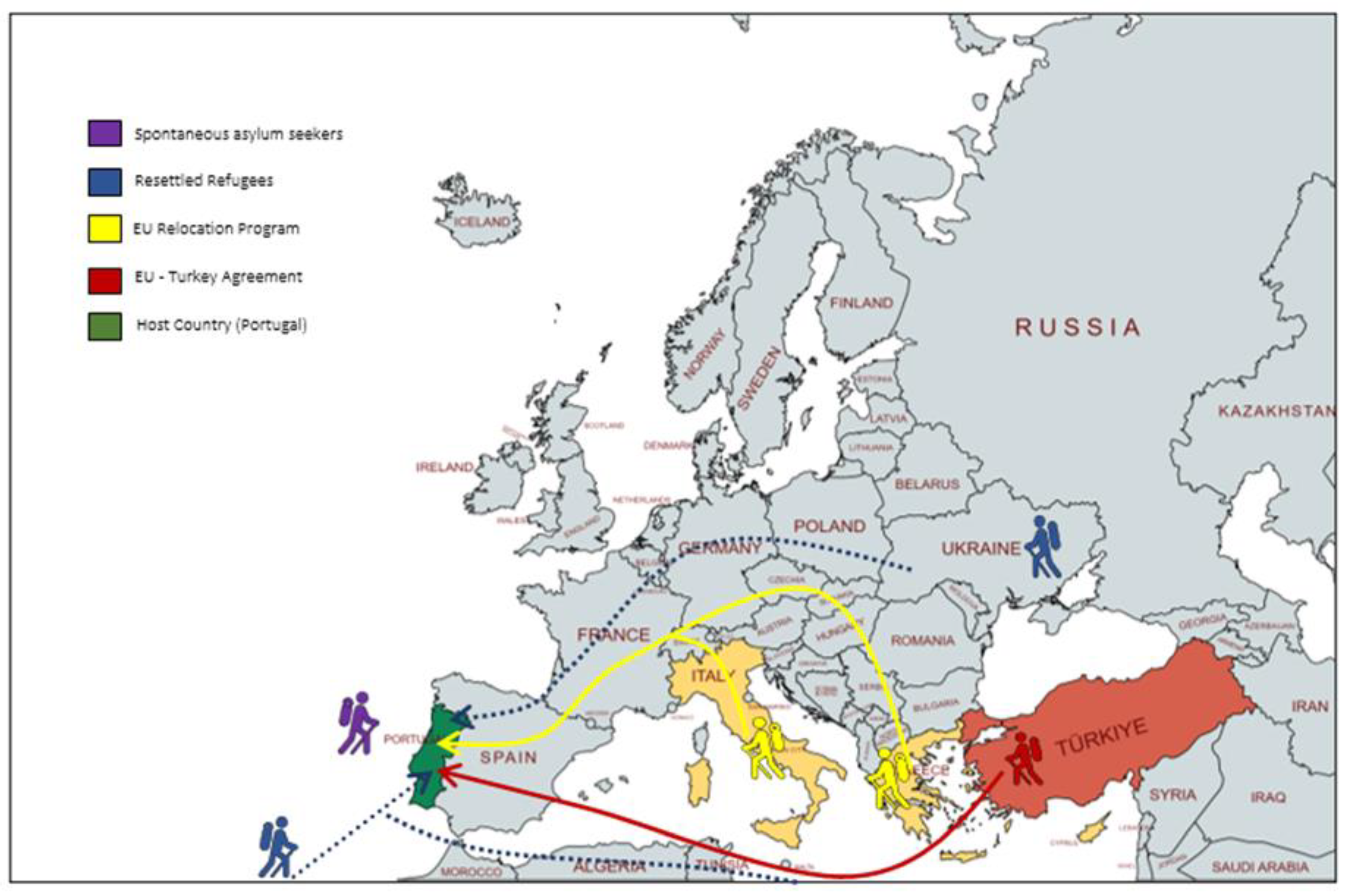

Refugees and asylum seekers arrive in Portugal through four possible channels (

Figure 1): spontaneous asylum seeking, via EU relocation and resettlement schemes, via EU-Turkey 1:1 agreement, and via Portuguese National Resettlement Program (OCDE, 2019, p.13).

Figure 2.

Humanitarian migration channes to Portugal. Adapted from OCDE (2019). Created on Mapchart.net.

Figure 2.

Humanitarian migration channes to Portugal. Adapted from OCDE (2019). Created on Mapchart.net.

The relocation of refugees and asylum seekers is framed in the Refugee Relocation and Resettlement Programs (CVP, 2022) and the workgroup for the European Agenda on Migration (order no.10041 A/2015), coordinated at a national level by the Portuguese Immigration Border Service (SEF) and the High Commission for Migration (ACM). Receiving asylum seekers within the EU Schemes demanded a systemic reorganization of Portuguese services involved in humanitarian reception and integration. Therefore, Portugal designed an 18-month decentralized integration program, involving several key actors [Immigration and Border Services (SEF), Portuguese Refugee Council (CPR), High Commission for Migration (ACM), Institute for Social Security (ISS), Institute for Employment and Professional Training (IEFP), Refugee Support Platform (PAR), Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS), Hosting Entities (municipalities, NGO’s and Foundations], prepared to support the integration of refugees and asylum seekers in areas such as—housing, health, education, employment and language (see OCDE, 2019, p. 21).

The Portuguese Red Cross (PRC) is one of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFCR) national societies working in the integration of Middle East and North African refugees and asylum seekers through the European Union (EU) relocation program (CVP, 2019, 2022). The PRC strives to prevent and alleviate human suffering in Portugal and the world. Its’ mission is to provide humanitarian and social assistance, especially to the most vulnerable by preventing and repairing suffering and contributing to the safeguarding of life, health, and human dignity [Article 5, Decree-Law No. 281/2007, August 7th]. The PRC approaches several action areas such as psych-social support, professional training, and education, first aid and emergencies, health interventions, and integration programs. The refugees’ reception and integration support is one of the actual central intervention areas of the institution in Portugal (CVP, 2022) as well as in other Red Cross National Societies across the European Union (Le Noach & Atger, 2018).

Middle East citizens make up a minor percentage of migrants arriving in Portugal despite the growing numbers after 2016 and the presence of Syrian and Iraqi citizens in the top rank of nationalities arriving in Portugal under the international protection law as refugees or asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2022b). Of the 2405 Refugees arriving to Portugal in 2020, 1014 were from the Middle East and North Africa regions (UNHCR, 2022b). Hence, the support for refugees and asylum seekers from Eritrea, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan has increased in Portugal since 2016 (UNHCR, 2022b) and PRC has been one of the NGOs hosting a major number of refugees and asylum seekers, intervening in the operationalization of the refugee integration efforts alongside governmental administrative bodies and other non-governmental institutions (CVP, 2019).

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Afghans constitute one of the largest refugee populations worldwide. Globally, Afghanistan’s political and social crises generated an estimated 3.4 million refugees and displaced citizens, most of them children, adolescents and women. Violence, fear, deprivation, the constant threat to the human rights of women and girls, and the economic and health system collapse are the main reasons for Afghans abandoning their country (UNHCR, 2022a). Despite their growing number in Portugal, Afghans are still a minority within the migrant population which can constitute an additional challenge for the integration process. In 2021, Portugal has received more than two hundred Afghan asylum seekers, most of them unaccompanied minors and women, fleeing Afghanistan under the international protection law after the Taliban occupation of Kabul and rising to power.

Portugal is hosting the fourth-highest number of Middle East and North Africa unaccompanied minors among the EU Member States after France, Germany, and Finland, and despite all the commitment and affirmation of its priority, the central Portuguese government, local authorities and non-government institutions are facing challenges regarding this highly complex integration progress (European Commission, 2021). Concerning the inclusion process, children and adolescents must be a priority for humanitarian institutions and the Portuguese central and local authorities, since it is known that minors recurrently migrate on their own because their chances of success are considered greater than those of older family members (UNICEF, 2017).

The term ‘unaccompanied minors’ refers to persons under 18 years of age who are separated from their families during the process of moving to the host country and who seek asylum. Adolescents comprise the majority of citizens arriving in foreign countries with this statute (Randell & Osman, 2021). Unaccompanied refugee minors are especially affected by conflicts, natural disasters, poverty, and threats to human rights since they are often exposed to continued violence in their home country and accumulative stress (Keles et al., 2016; Lustig et al., 2004) during a sensitive period of their mental and physical development (Huemer et al., 2009). Some can be victims of human trafficking and other forms of violence during the journey (UNICEF, 2017), and once in a new country, they also face specific stressors and challenges in the resettlement process (Keles et al., 2016).

Arriving in a new country without parental presence and support, while already carrying a social and health burden, can be stressful and disturbing (Löbel, 2020). This can explain the immediate and subsequent prevalence of mental health problems such as anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression (Mitra & Hodes, 2019; Mohwinkel et al., 2018), substance abuse, conduct and eating disorders (Pumariega et al., 2005) identified in this group. Additionally, uncertainty about their immediate/long-term future (Thommessen et al., 2015) and the often-stressful living conditions in the host country, including frequent housing relocations, limited access to education, social isolation and discrimination from peers and a sense of unprotection, can contribute to poor levels of health and wellbeing in unaccompanied refugee minors (WHO, 2018).

Notwithstanding the diverse instruments available in the EU on a legal, policy and funding level, the operationalization of several intervention programs Europe-wide has revealed the inefficiency of such interventions. This is related to the full implementation of the first and guiding basic principle of inclusion—which defines it as a “two-way process” (FRA, 2017). The conditions and procedures to provide international protection to citizens arriving in Portuguese territory are established in Portuguese law no 26/2014 in respect of the European Union 2011/95/EU directive and the 1951 Refugee Convention (UNHCR, 1951). Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that having a right under European or national law is not sufficient, it ought to be effective in practice (Le Noach & Atger, 2018) and this is the actual challenge.

Humanitarian assistance is crucial for the survival of displaced and refugee citizens, not only by providing shelter, nutrition, healthcare and water/sanitation but also for the protection of their human rights by providing education and information as the basis for active participation (e.g., integration in the labour market) in the development of modern multicultural societies.

2.2. Refugee and asylum seekers integration initiatives in Portugal

Portugal is an EU country with strong political and social inclusive measures. This idea is stated in the national constitution. There is a consensus among major political parties on the necessity of receiving and integrating refugees as a moral and ethical duty, but also due to the generally positive perception of the immigration effect on the national economy and demographics (OCDE, 2019, p. 43). The perception of the Portuguese civil society regarding the reception of citizens “from a different race or ethnic group than the majority” improved considerably between 2002 and 2018, being the 6th EU country more favorable to the presence of these migrants (Oliveira, 2022).

Despite the apparently favourable environment at different systemic levels, the integration process may often be negatively impacted by the high levels of institutional decentralization and bureaucratization regarding the relocation of refugees and asylum seekers. The coherent implementation and assessment of national integration programs may be hindered because of these two characteristics of the Portuguese system. At a local and regional level, some of the identified challenges are faced with the closer support of city councils and local non-governmental organizations that often mitigate the central government difficulties and faults in the reception, protection and integration of these citizens (Santinho, 2022, p.147).

Several governmental and non-governmental organizations have been cooperating at a national level since 2015 to apply a strategy of inverse inclusion, through the preparation of public-awareness campaigns on the immigration and integration of refugees (e.g., “Immigrant Portugal. Tolerant Portugal”; Welcome Kit; “What if it were me? Packing a backpack and leaving; magazine “refugees”) (OCDE, 2019, p. 44). Despite, the sustained effort in raising public awareness/sensitization to immigration and refugee topics being considered an example of good practice among OECD countries (OCDE, 2019, p. 46), there is more to look after regarding the planning and assessment of such campaigns to inform new and more efficient initiatives.

Different integration initiatives were implemented in Portugal regarding the support to the integration process of refugees and asylum seekers citizens. The authors performed a systematic and manual search for Portugal-based interventions. Only one study was identified describing communitarian projects within the arts (Santinho, 2022). Further information regarding the existent integration initiatives was accessed only recurring to an online manual search and data crossing of different information sources, which might lead to a search incompleteness or bias. Admitting this limitation, at the following topic the authors present examples of Portuguese-based integration initiatives directed to refugees and asylum seekers.

2.2.1. Global Platform for Syrian Students

The Global Platform for Syrian Students was established in 2014 by former Portugal president, the late Jorge Sampaio. Since the arrival of the first humanitarian plane to Portugal on the 1st of March, many other groups of Syrian students were accepted into Portuguese Universities and Polytechnic Colleges for protection and continuity of their higher education. For many of these students, the “scholarship was a turning point in their lives”. Nowadays, many of these students have completed their studies and started working while well integrated into the Portuguese Community. There are already Portuguese-Syrian families, and some are now Portuguese citizens (Global Platform for Syrian Students, 2022).

2.2.2. Artistic Community based Projects (Drama, Music and Dance)

Arts have been applied as a vehicle of integration. Santinho (2022) briefly describe examples of Portugal-based integration programs such as the “RefugiActo” Project that began in 2004 within the first resettlement Centre of the Portuguese Council for Refugees (PCR). The main aim of the project was to facilitate the learning of Portuguese and social inclusion through drama activities (Santinho, 2022, p. 150). The “Living Culture Band” derived from another intervention, the “Living in a Different Culture

3”. This activity was led by a Portuguese language teacher, also an amateur musician. Through what seems to be a natural mentorship process, the teacher mediated proximity and trust bounds between group members facilitating their integration and the sharing of cultural patrimony through the play of Portuguese (fado), Eritrea and Cameroonese traditional music. A third example of integration intervention with refugees and asylum seekers, “Une Histoire Bizarre” a theatrical play that uses the voice of fifteen migrants and refugee citizens living in Portugal and four Portuguese actors. The group was composed by men and women of different age groups from nine different countries (Sudan, Syria, Pakistan, Mozambique, Iran, Ukraine, Nigeria, Afghanistan and Gambia), without previous competencies in dramatic performance (

https://www.unehistoirebizarre.pt/). The play script was developed using their own life stories, memories, dances, songs and poems from their countries of origin (Santinho, 2022, p.157). An inquiry to the group members and public revealed that this initiative contributed to the decrease of generalization and negative perception of Portuguese audience towards migrants, the increase of self-esteem, confidence and the breaking down of “cultural gender barriers” within the participants (Santinho, 2022, p. 158).

2.2.3. Sports based initiatives

The “Welcome Sports Club” (Social Innovation Sports), “Welcome Through Football” (Benfica Foundation and social partners) and “Every Club, a Family” (Portuguese Football Federation) are good practice examples within the sports sector.

The general aim of the “Welcome Sports Club (WSC)” project is to promote the integration of refugees and beneficiaries of international protection—the youngest, including unaccompanied minors—advocating for their social inclusion, integral development, and promotion of intercultural dialogue. Social Innovation Sports (SIS) a National Association whose mission is to “promote sport as an asset of social interest at the service of communities, families, young people and children in vulnerable contexts”, is responsible for this project (Positive Benefits & Social Innovation Sports, 2023). To attain these social goals, SIS apply non-formal education strategies within sport contexts (Football, Cricket, and other physical activities and sports). Moreover, the organization also facilitates the job market integration by accompanying the beneficiaries in the process of preparation for employability, mentoring and exploring/matching the needs of the Portuguese companies. Between 2020 and 2023, SIS supported 91 unaccompanied refugee minors, having weekly activities with 35, from which 27 had professional experiences and 16 have currently part-time (student) or full-time job contracts.

“Welcome Through Football” is founded by Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union and the UEFA Foundation for Children. Benfica Foundation (Portugal) is an integrated club alongside other ten European football clubs. The project aims to assist in the integration and inclusion of recently arrived young refugees, asylum seekers and young people with a migrant background (7-25 years old) to get them physically and socially active in European communities (European Football for Development Network, 2023).

“Every Club, a Family” is another example of a social integration intervention through football. The Portuguese Football Federation and the associated football clubs have created conditions for 70 young athletes from Ukraine to continue to compete. The clubs associated with this program are encouraged to support an adult in finding a job while offering football training opportunities to the children or minors in the household (Portuguese Football Federation, 2023).

2.2.4. Mentoring based interventions: Mentors for Migrants Program

Mentors for Migrants is a countrywide program based on experiences exchange, help and support between volunteers (Portuguese citizens) and migrants and/or Refugees. The program aims and the responsibilities of both mentors and mentees are well defined (

www.mentores.acm.gov.pt) on the program webpage. The matching process is described and available to potential participants. Nevertheless, the researchers were not able to find program manuals or evaluation reports informing on the mentor profile, overall program structure, timelines or preliminary results.

2.3. The example of the Portuguese Red Cross Temporary Resettlement Centre for Afghan Asylum Seekers Integration actions (2022)

In December 2021, Portugal received 273 asylum seekers from Afghanistan. This group, the majority comprised of minors and young adults from a national music institution, came to Portugal in search of security, health and education, carrying the hope of being able to “safeguard the musical tradition of Afghanistan for the future”. Since the Taliban’s regime take over the governance of Afghanistan, fundamental human rights such as access to education and culture are under threat. Music and artistic performances were banned, and women lost many of the rights they achieved in the past decade.

The PCR received this group in a temporary Refugee Reception Centre of the Portuguese Red Cross, assuring safety, shelter, and supporting the beginning of the overall integration process in Portugal (education, housing, jobs, etc.). Recognising the migrant’s risk factors for health problems and poor well-being during different phases of migration (WHO, 2018), the coordination and educational team intervened preventively by creating opportunities for education and health protection/promotion besides the traditional actions planned in the relocation program implementation (e.g., psychological support, medical support, school integration).

2.3.1. Educational and Cultural Activities

Portuguese governmental bodies and the PRC promoted school integration early in the process. Part of the young students of the National Music Institute of Afghanistan also was able to continue their musical studies at the National Music Conservatory of Lisbon while at the Portuguese Red Cross Temporary Resettlement Centre.

Additional opportunities to learn the Portuguese language—25h course (mainly for adults of this group)—were promoted through a collaboration partnership between PRC and the ONG “Corações com Coroa”. Cultural activities were available to all the beneficiaries aiming the social integration through informal opportunities to learn the national language. The “Red Cross Youth Group” also promoted a workshop session on the prevention of addictive behaviours.

2.3.2. Sports Activities

Education and Sports are universal rights that, in emergency situations, guarantee dignity as well as physical, psychosocial, and cognitive protection, providing safe learning settings where vulnerable children and young people can be supported. Considering this, a communitarian partnership was celebrated between the Portuguese Red Cross (PCR) and the Alumni Association of the Faculty of Human Kinetics/University of Lisbon (Rede Alumni INEF-ISEF-FMH). For the implementation of integration initiatives through sport and culture, PRC and Alumni-FMH had the support of Social Innovation Sports (SIS). SIS served as a bridge between the Alumni-FMH volunteers, the PRC technical team and other institutional partners (e.g., Benfica Foundation, Portuguese Sport and Youth Institute, Portuguese Football Federation, Municipality of Alcântra, etc.). This cooperation is perceived by the elements involved as crucial for the development and implementation of a Sport Inclusive programme.

The first phase consisted of the definition of aims, implementation strategy, resources collection and organization. The strategy for the definition of the type and organization of the sportive activities to offer was based on the intersection between the beneficiaries’ personal interests (e.g., applications of questionnaires and informal conversations) and the availability of volunteer-sport technicians, equipment, and indoor/outdoor convertible sports spaces. Simultaneously, Alumni-FMH organized an open activity at the Jamor National Sport Centre aiming to promote the interaction between the Afghan beneficiaries and the Portuguese community through the experimentation of diverse outdoor sport activities (e.g., Canoeing, Cricket, Soccer, Portuguese traditional games, climbing, etc.). The collection of individual sports equipment was also successfully organized during this phase, allowing to the acquisition of the material requirements (e.g., sport clothes and tennis, sport equipment) to further implement the sport internal activities.

The second phase, anticipating the activities implementation, consisted of the baseline assessment of sport interests and competencies of the beneficiaries. Considered this information, the technical team organized a sport activity offer of football (2x week), multisport activities (1x week) and an aquatic competency assessment. Likewise, the team made available dance lessons (1x week) and yoga sessions (1x week) according to the competencies of the volunteers that spontaneously approach the Alumni-FMH recruiters to integrate this initiative. All the activities were mediated by certified Sport Coaches and/or Physical Education Teachers.

Swimming was another sport activity highly appreciated by a high number of beneficiaries, however, was not possible for the team and partners to set the swimming activities due to space restrictions. Nevertheless, it was possible to promote an aquatic competency assessment that showed a considerable hiatus between the perceived (e.g., “I know to swim autonomously”) and the real (“initial stage of foundational aquatic locomotion skills”) aquatic competence of the beneficiaries, which was a point of concern for the team as it represents and increase risk of drowning (Willcox-Pidgeon, Franklin, Leggat and Devine, 2020). Answering this data, the PRC team decided to promote an evidence-based workshop on Drowning Prevention (Carolo, 2022) and mediate the contact with a typical Portuguese beach through a wave sports activity.

Football and dance internal activities were perceived as having a great success among the beneficiaries by generating extensive health promotion and social inclusion opportunities for beneficiaries (e.g., integrating Benfica Foundation Teams, playing football with community members regularly; being invited by the board of a Portuguese Public school to a celebration activity of the World Dance Day). Football and Dance lessons facilitated the liberation of emotions in a sublime manner, supporting the celebration of their embodied nature, culture and friendships through movement and energy expenditure. Particularly, the dynamization of Dance lessons revealed a potential for therapeutic impacts. In the context of this six-month intervention, the aim of the Dance professor was, firstly, to promote health and well-being by providing a safe space to express themselves and share through dance and visual arts. Secondly, to learn basic movements from classic and contemporary dance, considering their baseline skills and interests.

Moreover, collaboration initiatives between PRC and external community partners allowed answering to the particular interest of the beneficiaries who preferred other sport activities than the ones offered internally (e.g., Gym, Parkour, Boxing).

The volunteer PRC/FMH Alumni team highlights the perceived motivation of the beneficiaries to practice regular sport and physical activities aligned with their interests and motor competency level. The main challenges identified are related to the compatibility between the time availability of the beneficiaries and the availability of space and trained volunteers, as well as communication/coordination with the beneficiaries for the logistical implementation of the activities (e.g., language barrier).

As for future guidance and recommendations, it is considered that the availability of financial and human specialized resources will be important to register the beneficiaries in externally organized activities, for safe transport, and payment for the specialized work of the technicians for a more constant and extended intervention, an aspect that we consider not possible to accomplish fully by means of only consider the intervention of volunteers.

2.3.3. Mentoring as a Key Strategy for Social Cohesion and Integration of Afghan Unaccompanied Refugees minors and Asylum Seekers

Portuguese Red Cross (PRC) team working with the last emergency resettlement group of young Afghans in Portugal also identified empirically the necessity of develop an adapted mentoring program to support the integration of Unaccompanied Refugees minors and Asylum Seekers. Different dynamics of interaction between technical team members and beneficiaries were empirically identified as a natural mentoring process with potential positive results.

In this context of intervention, PRC technical team members identified that the youngest beneficiaries, mainly the most emotionally vulnerable, naturally elect a technician or facilitator with whom they share some details of their daily routine, share their anxieties, get information about the way the new national systems work, ask questions about the way of life and their educational or working opportunities in the hosting country or ask for advice about the choices and decisions about their future. From the perspective of the PCR technicians, the challenge was to support the emotional and physical health as well as advise the young unaccompanied asylum seekers without getting too attached or personally involved. This is particularly difficult, because of recurring emotional highly loaded situations experienced.

A strong personal involvement by technical team members, despite its best intentions, can hinder the next phase of integration in the host country in which the emotional and functional autonomy of the migrant citizen is crucial. Thus, it is crucial to coach technical team members and PRC social educators to intervene in this specific context.

The definition of a mentoring training program within the PRC can facilitate future interventions. Moreover, the involvement of national research centres and universities through collaboration protocols may be beneficial for the development of valid programs, evaluation tools and technical-scientific reports needed for the development, implementation and evaluation of an effective, valid and feasible mentoring process.