1. Introduction

The management and supply of water in a productive and recreational center such as a Roman villa was one of the needs that every owner had to fulfil. Generally, a water supply was required for human consumption and cooking, which came from wells or salubrious springs. A larger quantity was used for irrigated agriculture or for animal consumption, which may come directly from streams and rivers, but did not require the same quality of drinking water. Therefore, there was a large use of water for the recreation of the owners, generally in fountains, pools, and thermal baths. Studying how this water circuit worked, where the water collection points were, how it was distributed and in what way, requires a broad knowledge of Roman architecture and hydraulics, which is difficult to recognize in archaeological cases due to the lack of studies and precise contexts. In this regard, there are few cases of similar studies, especially concerning the involvement of non-invasive methodology or Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis of the archaeological remains [

1,

2]. There are cases of hydraulic exploitation, but they are focused on large architectural complexes and urban supply, such as the Roman cities [

3].

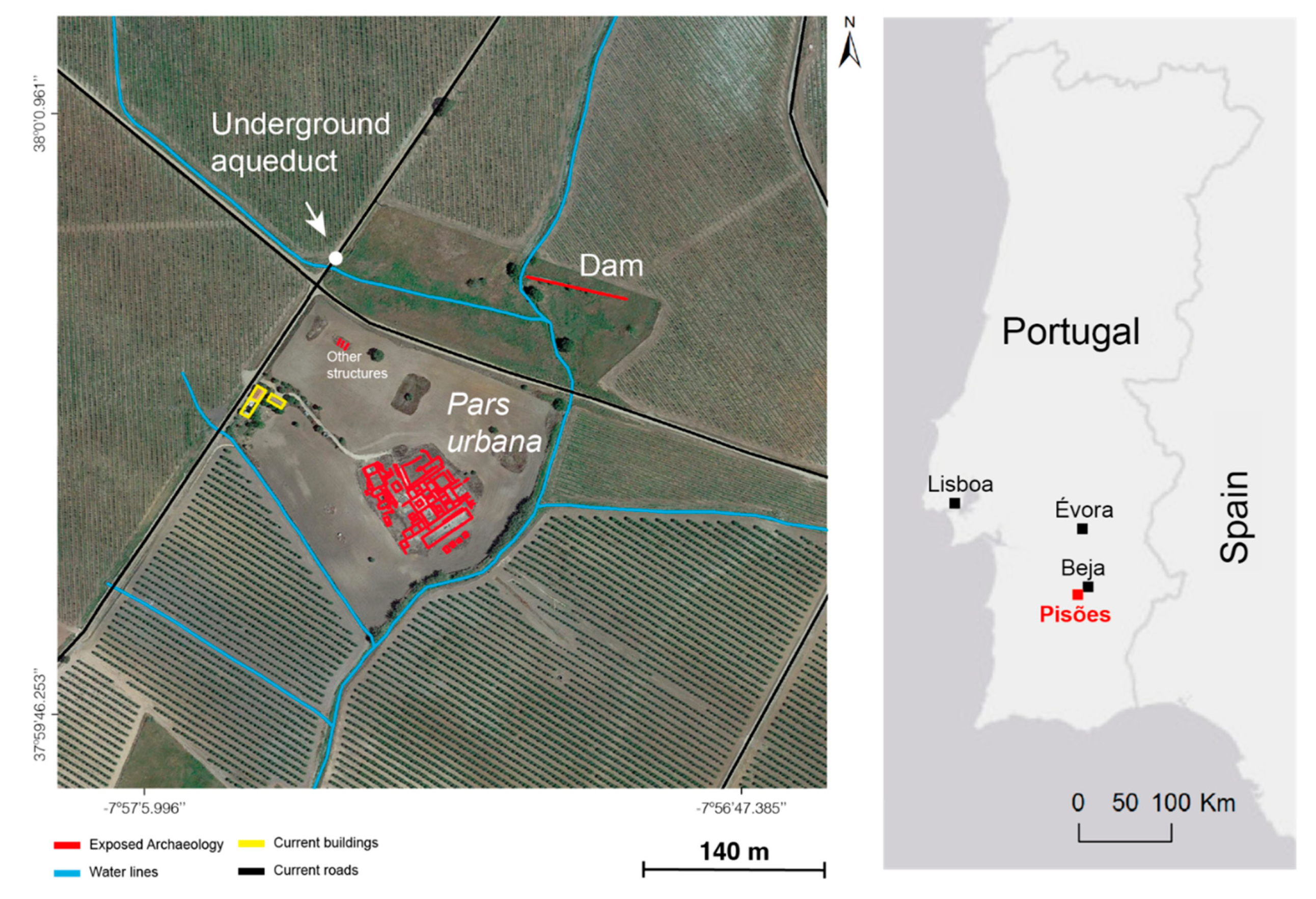

This work describes a case study of the Roman villa of Pisões, classified as the property of public interest in 1970, located in Santiago Maior (

Figure 1), 10 km southwest Beja.

The archaeological remains of the villa complex extend well beyond the protection area of approximately 6 ha divided into two adjacent areas. In the eastern area there is a Roman dam [

4], while in the west part is located the center of the villa. Although the remains areas are extensively excavated and the main results have been published, the reality is that Pisões was found by chance in 1967 when a tractor pulled a mosaic out of the ground. The excavation began immediately, coordinated by Fernando Nunes Ribeiro, one of the benefactors of the regional museum of Beja and at the time mayor of the municipality [

5]. Although he had a great archaeological experience, he was not an archaeologist, but a veterinarian, which meant that the excavation was carried out without the appropriate rigor and methodology. For example, we do not know for sure when the foundation phase of the villa took place, although from the planimetry we can assume that it was sometime in the 1st century AD. Likewise, we do not know the duration of the occupation or when it was abandoned, nor its phases and stratigraphy. Some archaeological materials collected in the area from the Visigothic period maybe up to this chronology.

The villa has 48 excavated rooms, centralized in a small peristyle with four columns, a rather original architectural plan for this type of site [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. It comprises a small but complete thermal complex to the west, with a second peristyle attached, several access passages with mosaics and a large corridor leading to a monumental

natatio measuring 39 by 8 meters [

11]. Although it has never been well publicized, Pisões is a relevant villa as far as we can tell from an inscription, consecrated to the goddess

Salus by

Numerius, slave of

Caius Atilius Cordus, probably the owner of the complex by the 1st century AD. Given the importance of the villa, it is likely that there is a

pars rustica and a

pars fructuaria near the

pars urbana, but it has not been detected, although three marble wine or oil presses have been documented.

The villa belongs to the University of Évora since 2017 and is part of the Experimental Farm of Almocreva. In this place, it intends to install an experimental field for archeological sciences, to carry out multi-disciplinary research, in which Applied Geophysics is one of the sciences contemplated [

13].

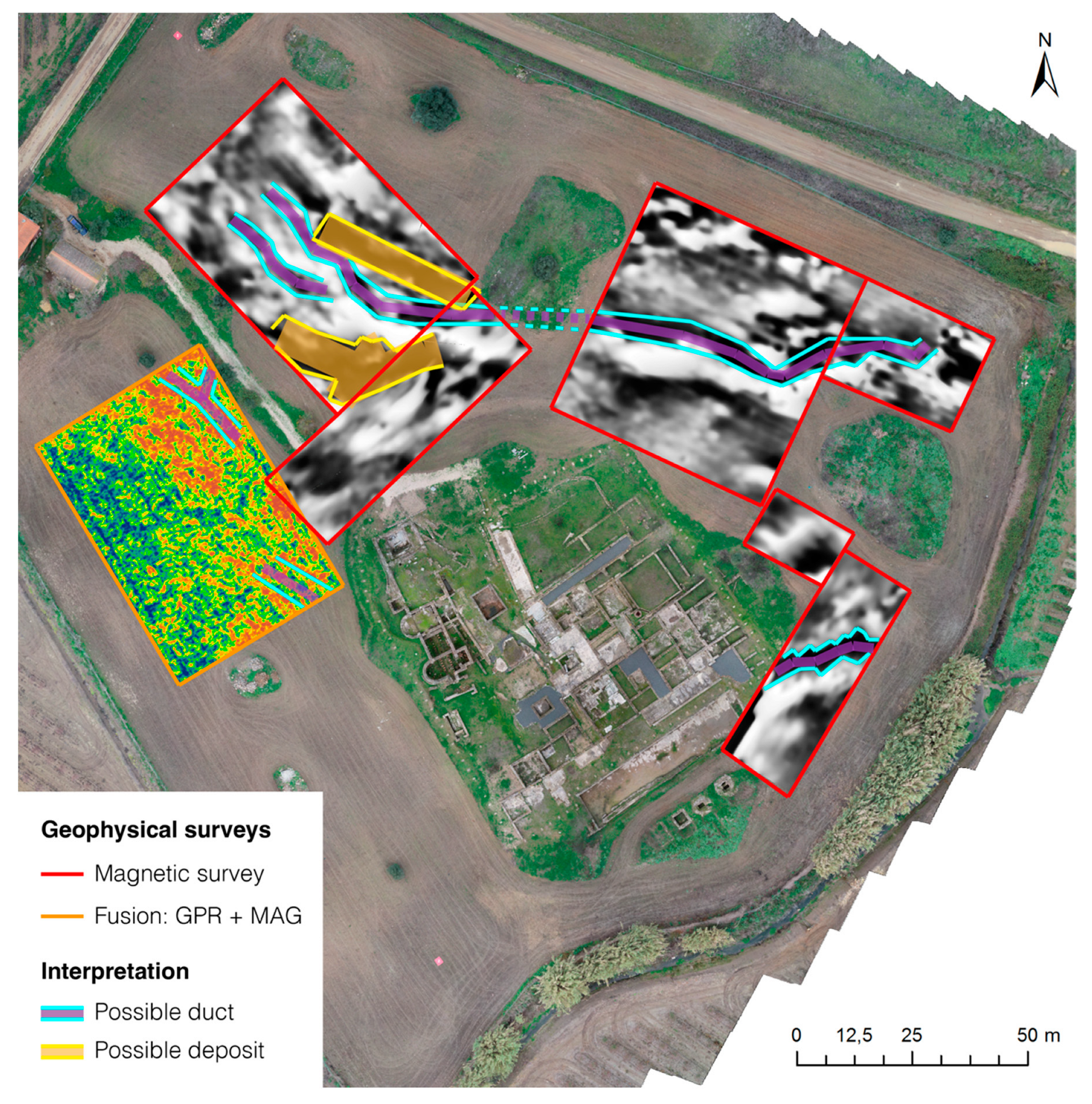

In 2017, several geophysical surveys have been carried out with different methods to prospect the subsurface and assess the state of conservation of some structures. Between 2018 and 2020 was carried out a magnetic survey (vertical gradient mode) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) in several sectors around the

pars urbana (

Figure 2) [

14,

15,

16].

In the context of this work, we would like to know how the water supply and its distribution for the hydraulic elements of the villa were articulated. To this purpose, we carried out an archaeological study of the emerging elements that can be analyzed and a series of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys around the perimeter and inside the site. This information has been georeferenced with a differential global navigation satellite system (GNSS), with centimeter precision, to determine the slope and direction of water flow. A geospatial survey with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was also carried out to obtain a photogrammetric model, to study altimetric elevations and their relationship with water transport. With all this we present in this article the results with a proposal of water distribution, relevant information for the interpretation of GPR data and hypotheses generated that can give us thoughts on the existence of other constructive phases that had not been put in sight.

3. Results

3.1. Detailed Analysis of Each Water Conduit

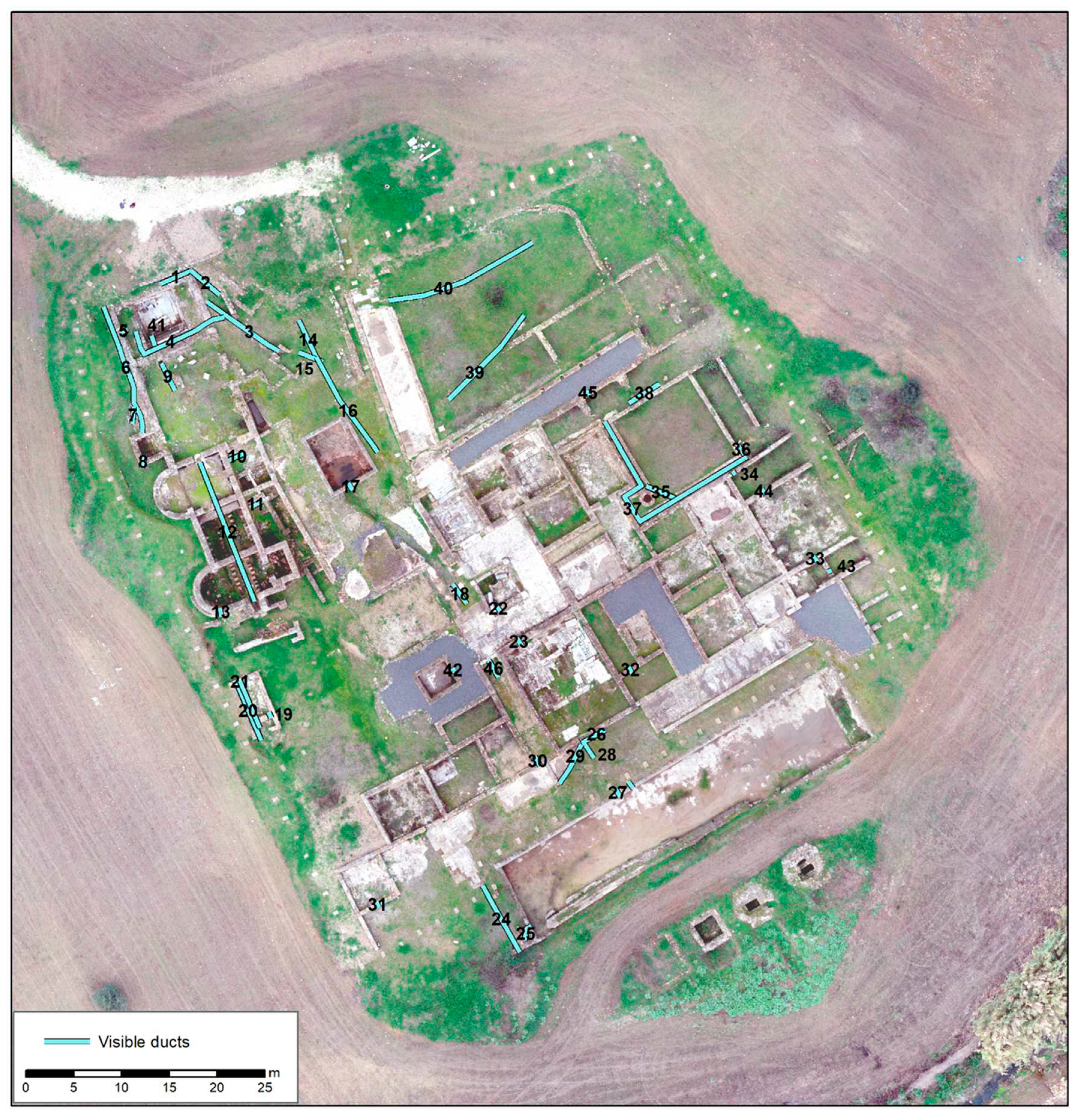

In the first stage of surface work, we have been able to discover a total of 46 water conduits in the villa, within which they serve different functionalities and may not be related to each other.

Figure 3 shows the visible conduits, which are described below in groups according to their function. The altitude values of the visible ducts were measured with differential GNSS (

Table 3).

Ducts 1 to 9 correspond to the original supply of the thermal building, where pipe 1 is at an elevation of 181.60 m, the highest topographical point in the whole villa. This part of the complex can be understood quite well, given that the water flows from pipe 1 and 2 to 6 and from there through 3, 4 and 5 to the natatio located there, the water exiting at pipe 9.

The ducts 10 to 13 are part of the main private therma or balneum, but only 12 and 13 correspond to the water exit of the whole, while the other two elements are isolated and at lower levels.

Ducts 14, 15 and 16 correspond to a very shallow water supply circuits which is difficult to pinpoint, as we can neither see its origin nor its end.

Ducts 17 and 18 correspond to the exit of one of the large pools and a small sewer that is visible near the center of the villa, which corresponds to pipe 46.

Elements 19, 20 and 21 are related to the latrines, a clean water inlet and a sewage exit.

Ducts 22 and 23 are the water exit of the central impluvium and the water inlet of one of the rooms, which due to its marble cladding could be a low recreational pool.

Ducts 24 and 25 are the water exit of the monumental natatio and possibly another conduit that takes water from other parts of the villa to this point, which seems to be a collector.

The remaining ducts are very difficult to identify. The elements 26, 27, 29 and 30, whose connection is not clear. The same for pipes 35, 36, 37 and 38, which seem to be related to a well located to the northeast of the villa. It is not clear whether element 40 is a wall or a conduit, but structure 39 is an aqueduct with manholes that must have supplied water to the town, given that it is located at a very high elevation. The remaining elements are isolated in the villa and in general, do not seem to be connected to other hydraulic elements. They are mainly holes in the walls measuring 8 x 16 cm which could well be elements for cleaning the rooms or even in the restoration and consolidation of the elements themselves to prevent the accumulation of rainwater.

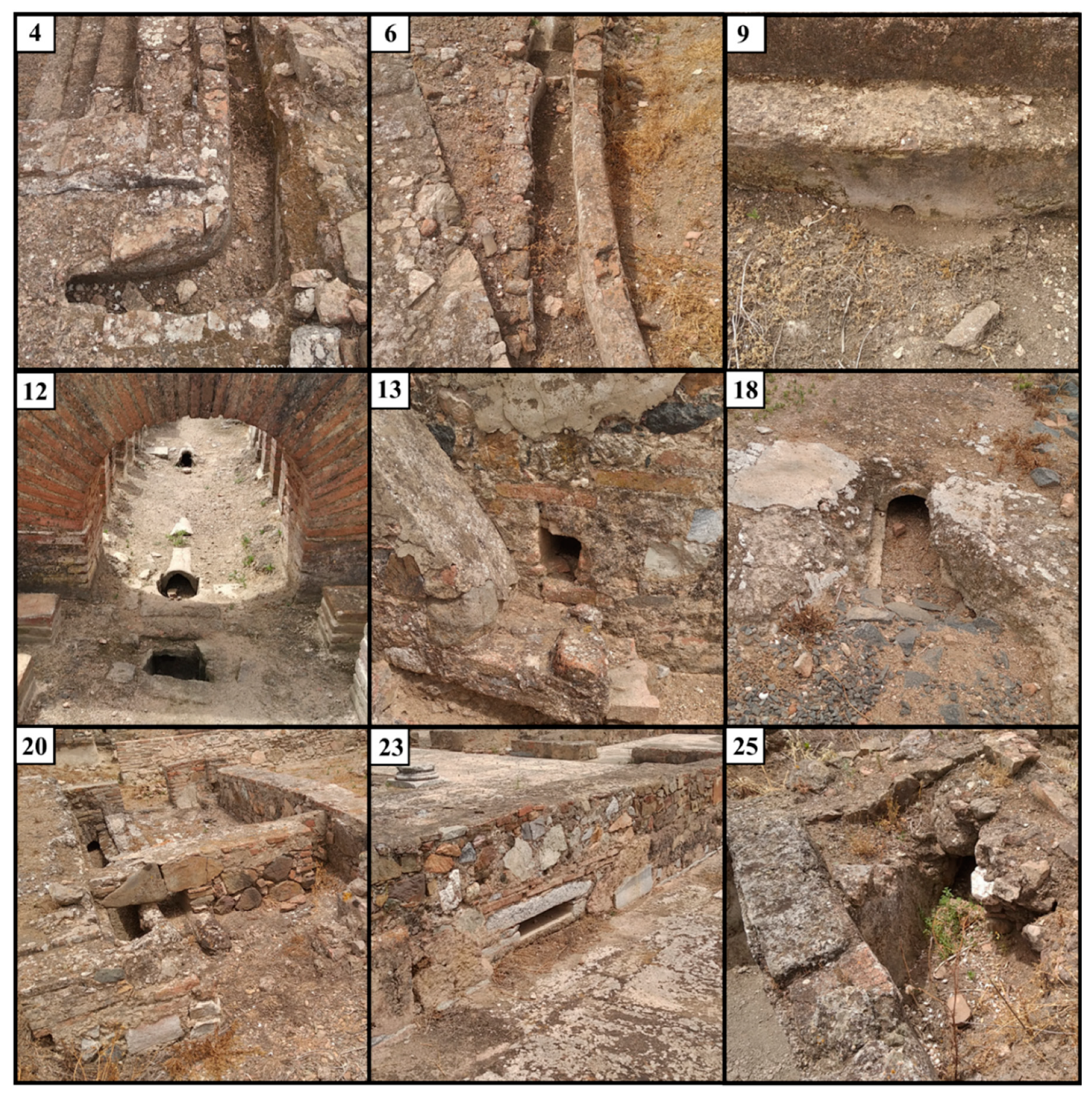

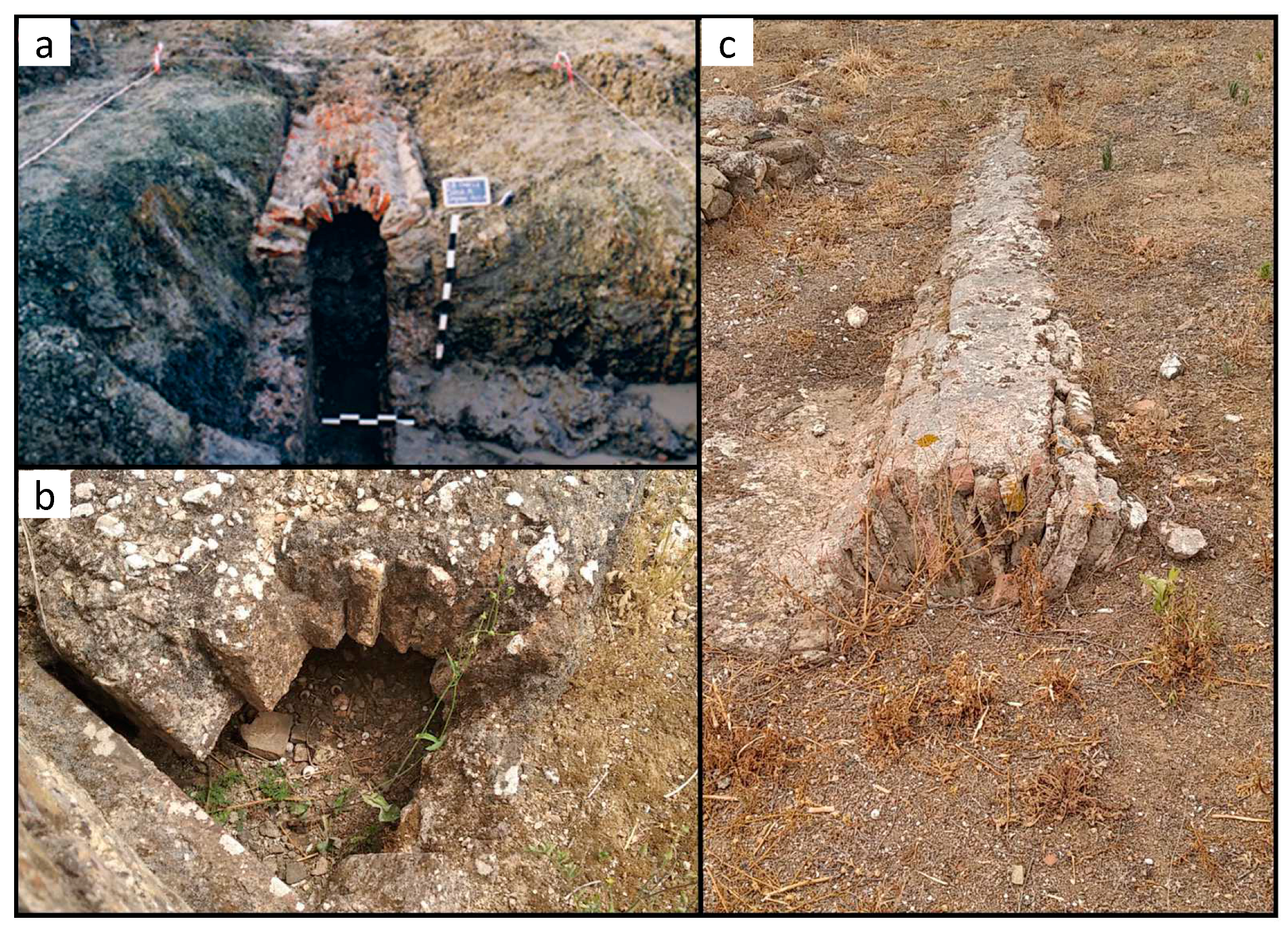

Figure 4 shows examples of the different elements that we have detected in the villa with a water conduction function, whose numbering corresponds to the structures identified in

Figure 3. Conduit 4 would be under the pavement and would serve to conduct water within the enclosure itself, while conduit 6 is on the side of the

balneum. Duct 9 is the water exit of one of the

natatio, and duct 12 is where the water would have gone, which can be seen on the floor of the well-preserved

hypocaustum with its brick basins. Element 13 is the only water exit that we have located on the side of the

balneum for the hot water. Structure 18 is the water conduit that would have supplied water to the center of the villa, while the number 20 is from the latrines. Structure 23 is a strange element that seems to be to supply water to the room which could be a low

natation. Finally, structure 25 would be the main sewage collector of the villa in a bad state of preservation.

Considering all the elements analyzed, the only water supply point, i.e., where it may have come from, is the conduit 39. This is a small, partially collapsed brick vault in which small access and cleaning well is preserved, as well as part of its roof being visible. This construction is very similar in shape to an aqueduct located at northeast of the villa [

18,

19] and which could be the access point for water from nearby springs. In addition, structure 39 is very similar in shape to number 11, so all three could be part of the same aqueduct, as can be seen in

Figure 5.

3.2. Structure Detection Using GPR

The results of the geophysical studies of the GPR and magnetic methods reveal that there is a great possibility of large structures existing in all sectors that surround the excavated urban part [

14,

15]. For Pisões, a problem of lack of perceptibility of buried structures was also identified, caused by the physical and chemical characteristics of the soil and the materials that make up the structures [

14,

15]. For GPR method, the size of the clay particles causes scattering to add to the strong attenuation characteristic of this type of soil. The characteristic hydration of clays also causes strong attenuation. Even with these conditions described, GPR surveys were carried out using antennas of various frequencies, until it was proved again which ones allow the best results to be obtained.

Therefore, the study carried out consisted of the acquisition of 38 B-scans around and inside the pars urbana, using antennas with the following central frequency values: 100, 200, 400 and 1600 MHz. The best antennas to prospect buried structures in archaeological context is the 400 and 200 MHz. However, at Pisões site, only the 200 MHz antenna allowed to see reflections compatible with structures, but near the border of the pars urbana we cannot detect any reflections. In the inner part of the pars urbana, the 400 and 1600 MHz antennas worked well, allowed the detection of buried structures.

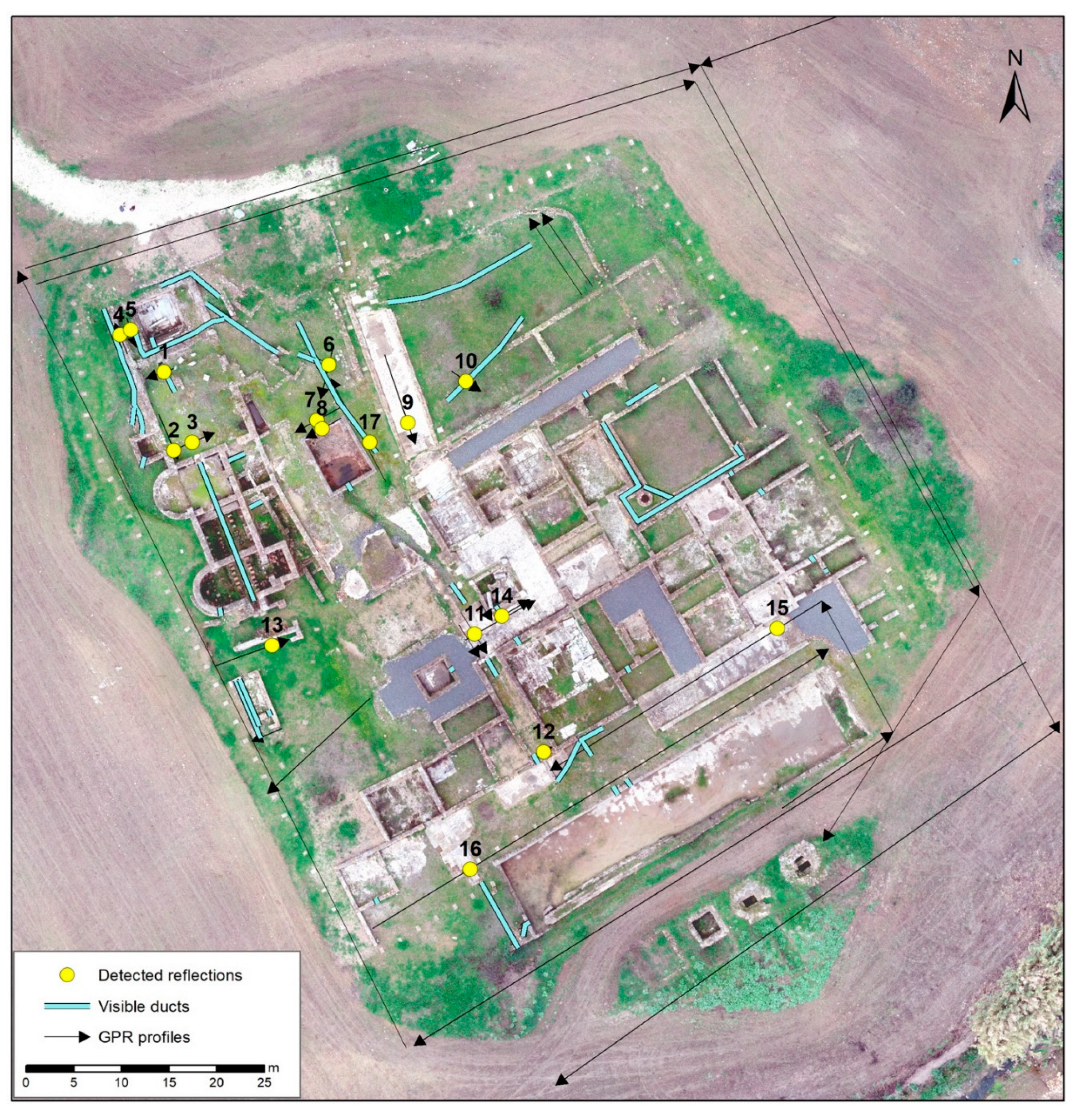

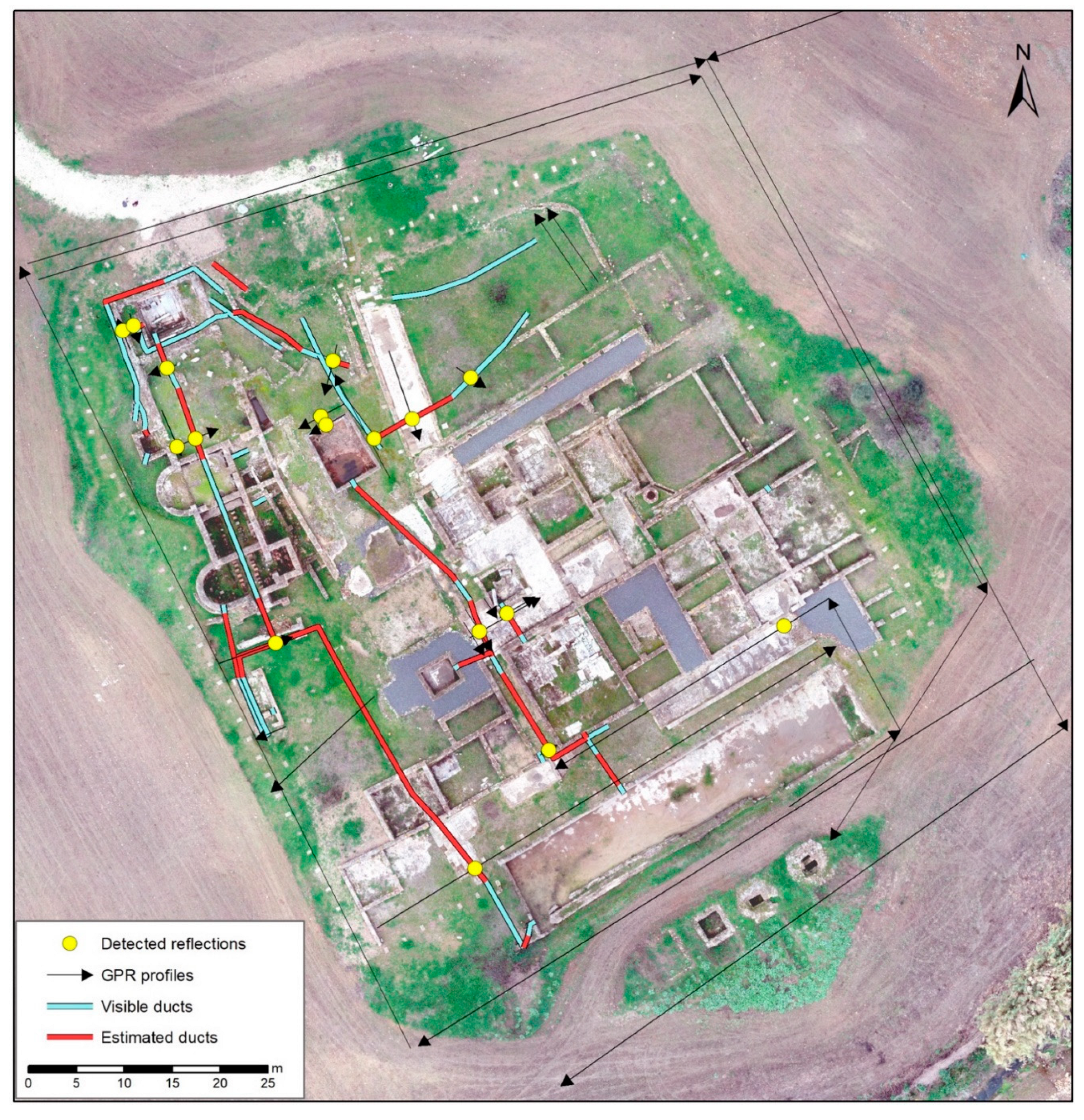

Thus, in the inner part of the

pars urbana 17 reflection patterns were identified in the B-scans, all compatible with water conducts, and at expected locations, near visible conducts or structure holes. The location of these patterns is shown in

Figure 6.

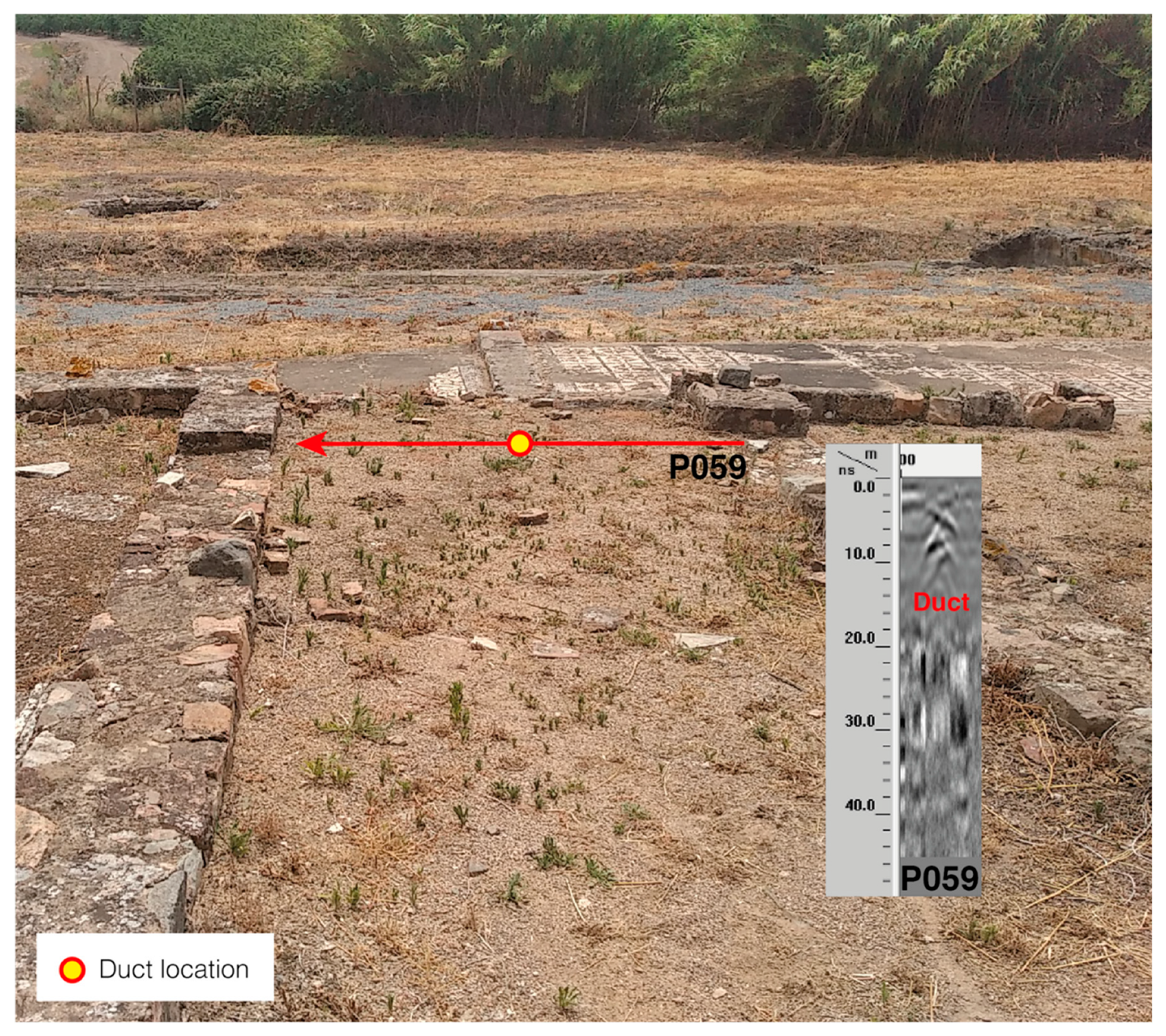

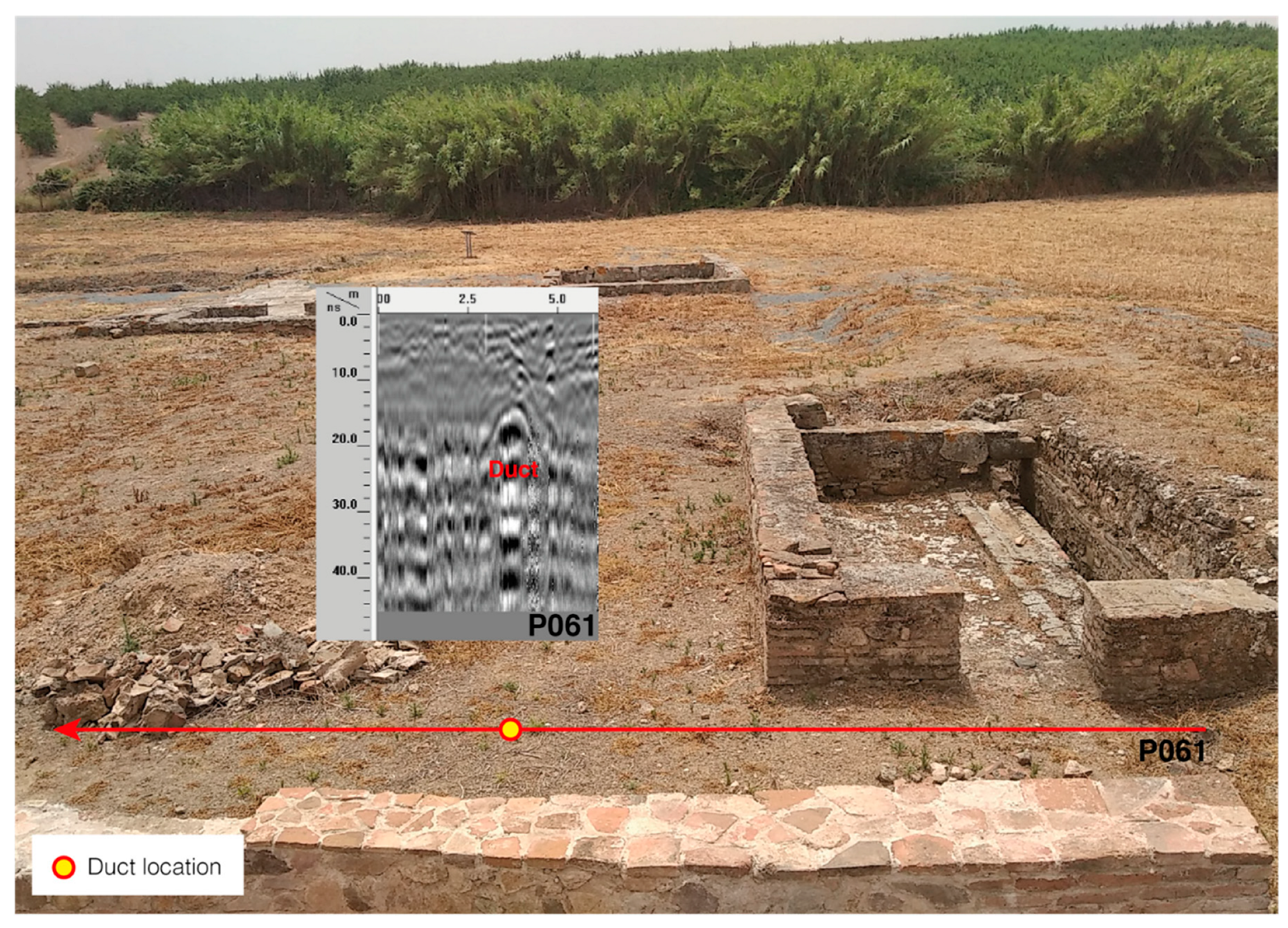

The results of GPR survey can be observed in the following figures. All B-scans are overlaid to a picture of the prospected sector in Pisões, with a schematic of the profile location and direction.

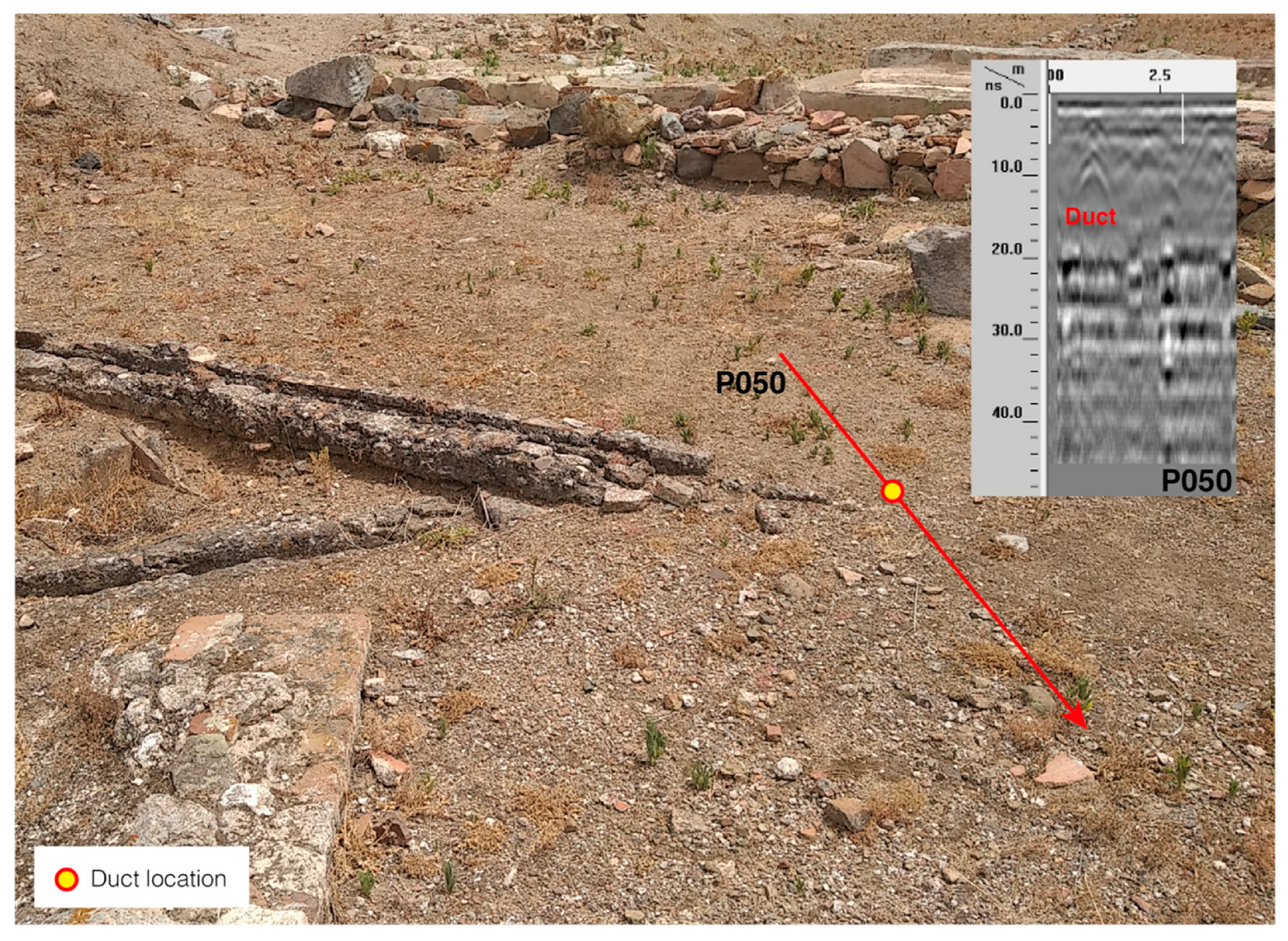

In

Figure 7 is shown a B-scan acquired near the remains of 2 conducts. However, just one is possible to observe and make the correspondence with the observed in the field. As these tubes are quite degraded, it is possible that part of them no longer exist.

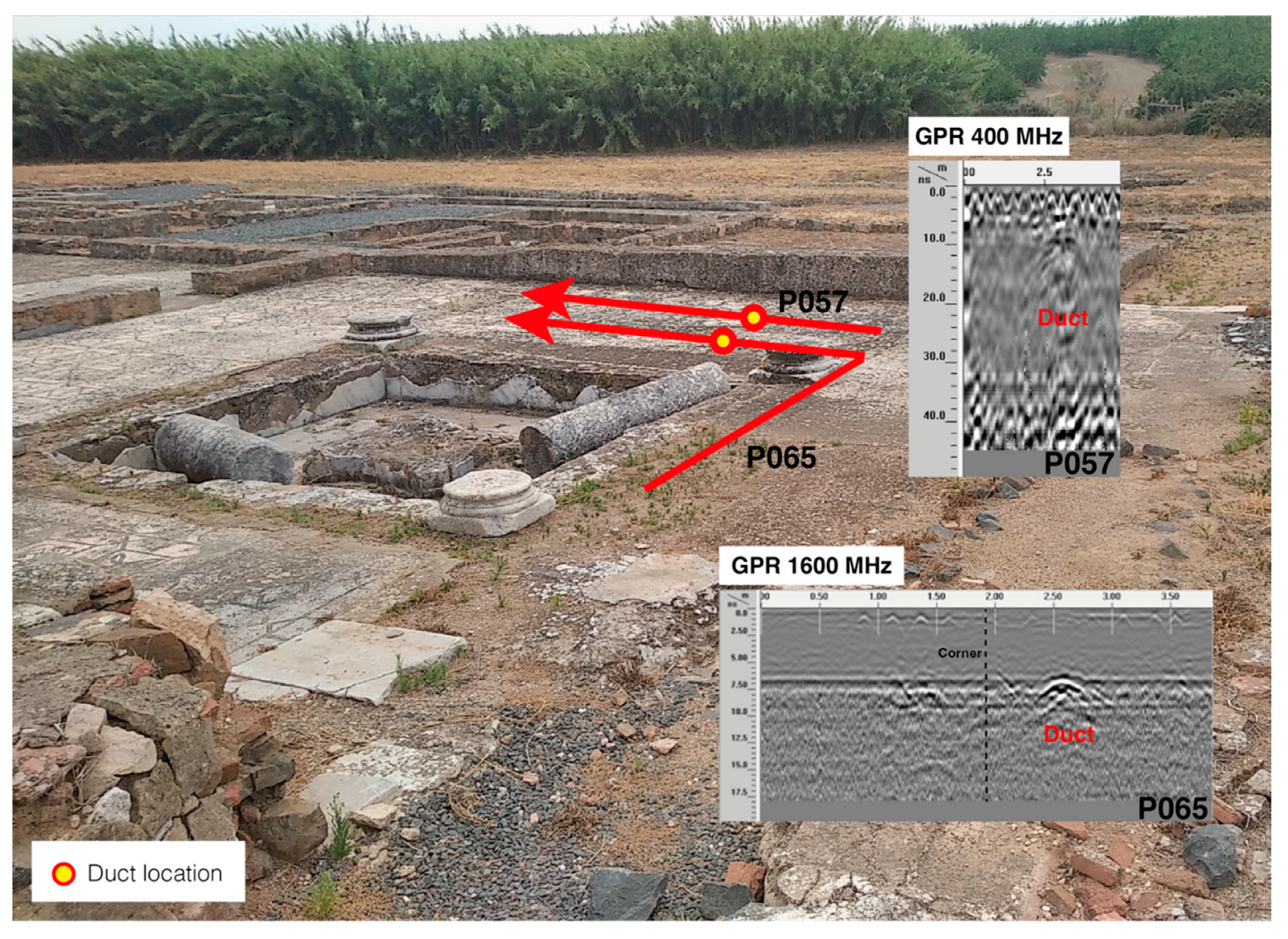

In

Figure 8 is shown 2 B-scans carried out with 400 and 1600 MHz antennas. Both profiles were acquired partially in the same location and shows a reflection pattern compatible with a duct, in the expected location of the

peristilum drainpipe. For small structures, 1600 MHz antenna allowed to observe more details.

Figure 9 shows the spatial distribution of an underground aqueduct. Near P054 B-scan we can observe the top part of the structure. The results show reflections compatible with a great conduct, which passes under the mosaic floor, continues towards the small pool towards the thermal baths.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 shows the B-scan reflections in the continuation of a drainage conduits.

4. Discussion

The interpretation of all information, whether archaeological, geophysical and geospatial, allow us to make several considerations in discussion mode.

Excluding from the initial analysis several conduits that are not related to the main entrance, such as some small ones in the rooms and others related around the well, we propose a series of conduits that should have existed, based on the combination of all the data (

Figure 12). The tracing drown was made by considering the connections between the visible and preserved elements that explain the water circulation of the main system. There is a high possibility that many of these features are not preserved on the surface, either because of the history of the site, such as the agricultural works. These problems may also have been detected in previous excavations, but the lack of technical information at that time does not allow us to know if this happened. Therefore, we can describe the water communications that seem to have worked at the time of greater expansion of the villa, when the main hydraulic elements were in operation. Added to this, is a series of elements located in the northwest that have no direct connection, and which may date from another phase, as will be discussed later.

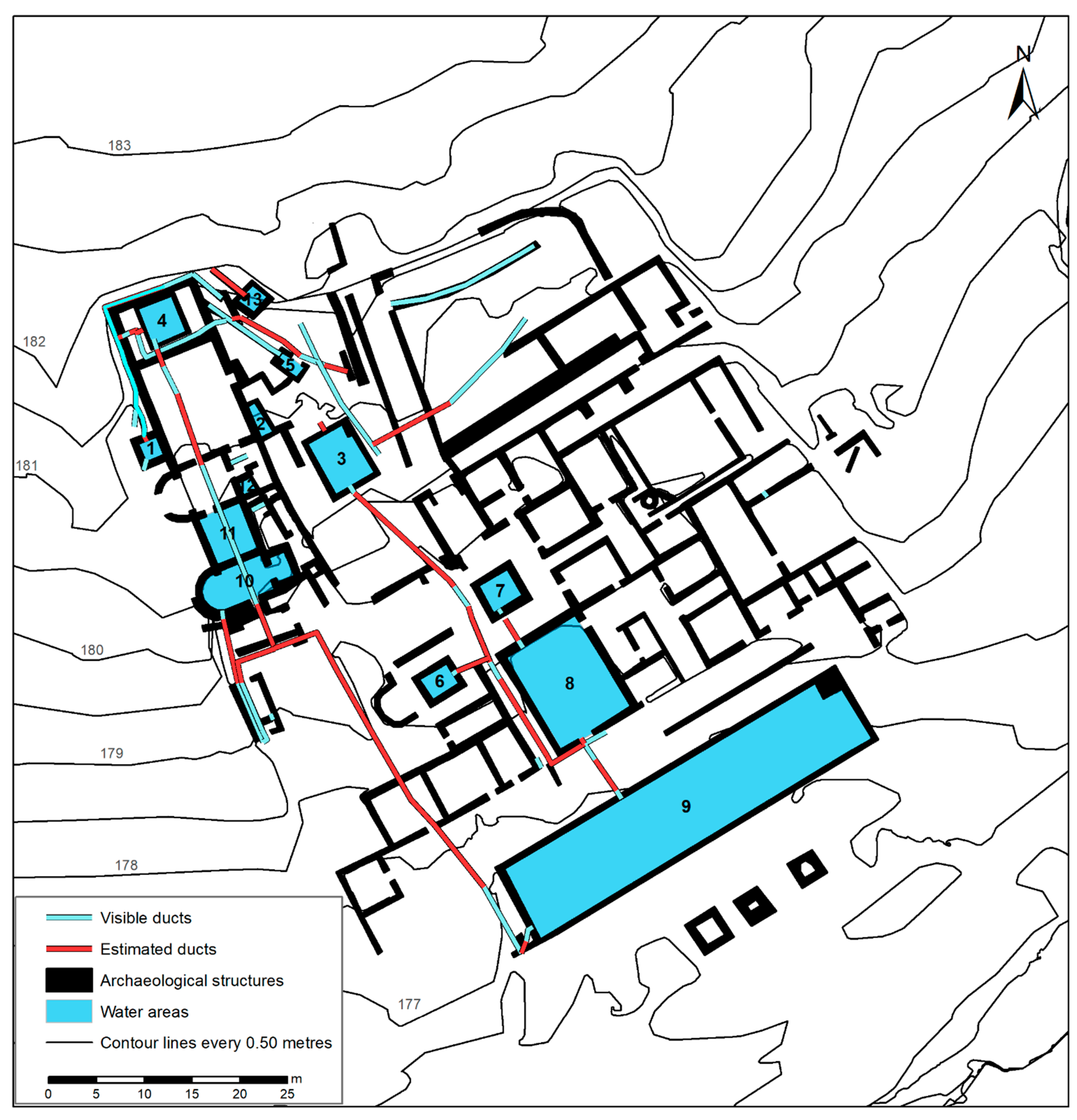

The detailed study between the visible water pipelines and those estimated by geophysics allowed us to reconstruct almost all the missing sections. The estimated sections are about twice the length of the parts that are currently preserved. The reconstruction of the main water connections can be observed in

Figure 13.

Considering the altitude values of the bottom part of conducts and water receptacles, we can suggest that the water access is located at the northwest corner of the

pars urbana, with altitude value of 181.60 m, the highest value measured in Pisões. The lowest value is in the large

natatio to the south part of the villa, with altitude value of 175.90 m. The villa is therefore distributed on a hill that slopes down in a south-easterly direction with a change in elevation of more than 6 m in total. The water supply must necessarily come from the northwest. Therefore, the main water access can be well reconstructed to supply the main hydraulic elements of the

balneum, corresponding to the elements 1 and 4 (

Figure 13). The first one would correspond to a

labrum supplied from outside the building, while the second would be a cold-water

natatio. This little pool has a hole that crosses the wall that supplies water to this structure, but there is a second conduit in continuation, confirmed by GPR method, but we have no further information about its distribution in space. It may be connected to

natatio 3, which we know that could have a water conduit to supply it. This element could be outdoors and therefore would not need an inlet pipe. In addition, no water passages are visible in the wall, although it may have been covered up during site restoration and consolidation.

Following the pipes to the balneum, we have no evidence of where the water enters for rooms 10 and 11, but there is some evidence that comes from the same place as for room 1. However, this part of the building is in a poor state of conservation. The exit from these rooms is identified in the southwest corner, after the structure 10. From pool 4, passing underneath the hypocaustum, there is a small sewer for dirty water which connects precisely with this exit, and we have found that it also connects with the dirty water that would have come out of the latrine. We can suggest that it is precisely at this point to the west that the wastewater from the entire bath complex and the latrine is concentrated. We have confirmed the continuation of this conduit makes a bend, although from there to the water collector to the south, together with the monumental natatio, was not detected. The geophysical data in this area do not give clear results.

From pool 3, which has a marble sluice gate, the water flows into another conduit that crosses the main path and stores the water from impluvium 6 and 7. In room 7, we observed that the water does not go directly to this conduction but to room 8, which is a low pool lined with marble. We did not detect any conducts between these two elements, but they are connected to take the water to the monumental natatio 9. It is possible that all these elements could be outdoors, with their distribution to the main pool and from there to the south exit collector that connects the water of these elements with the water of the balneum. We did not find elements implying that in water areas 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9 there is water supply from an aqueduct, but that it would be mainly rainwater. Even so, the entire complex could be supplied by pool 3 and, therefore, this would be a water reservoir in case the impluvium ran out of water.

With all this, we have another series of isolated elements that we have not analyzed. As we have already mentioned, the well to the east has a series of conduits around it, which we believe have to do with storage and cooking areas, whose water supply would be from the well itself. The same is true of the northeastern section of the villa, where there are a series of isolated conduits, such as the aqueduct mentioned above. To reach the knowledge of these structures it is necessary to locate the

pars rustica and

pars fructuaria of the villa, which requires the application of methodologies dedicated to this purpose [

20].

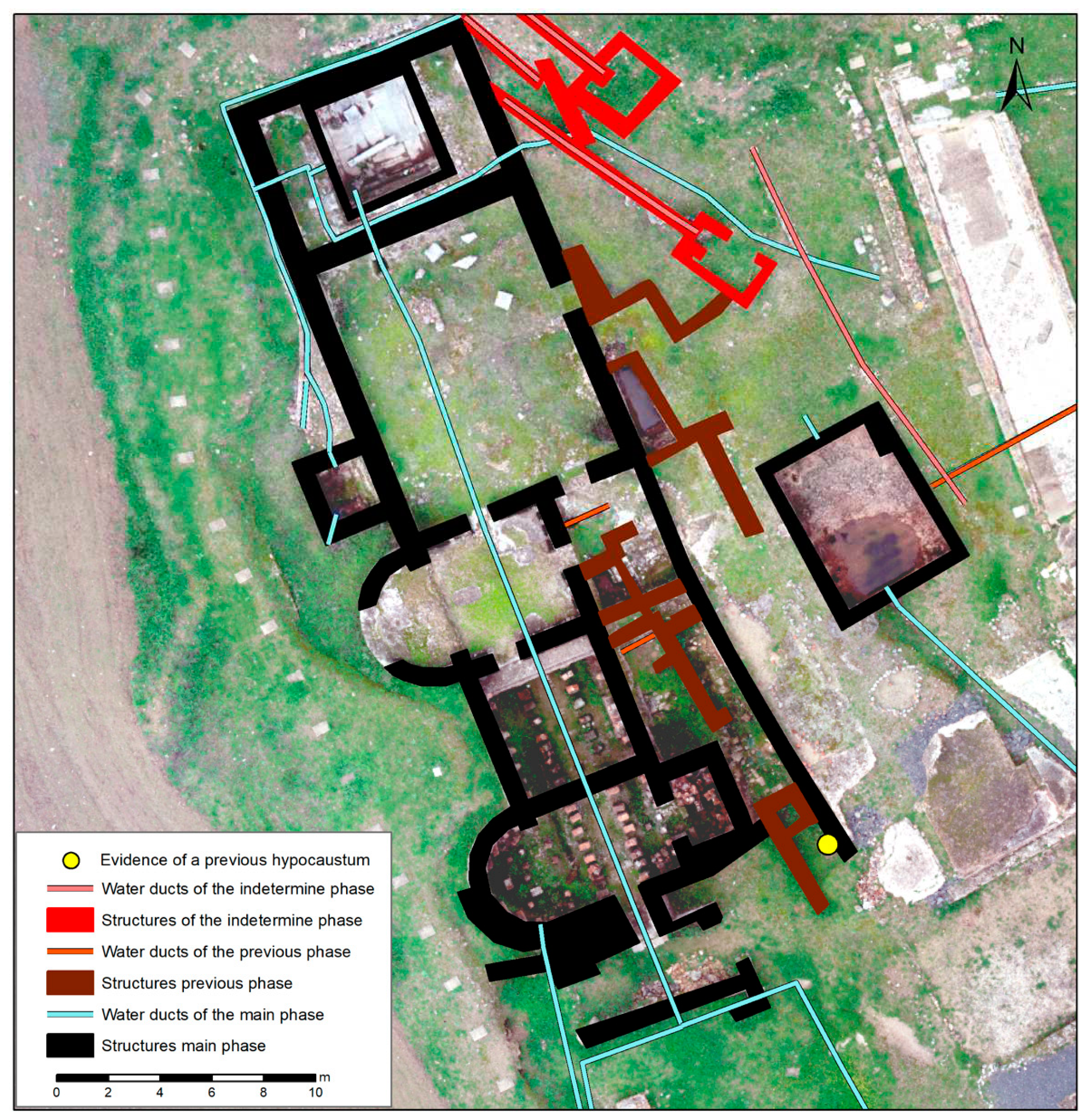

Above this element, we have a series of pools that have been interpreted as part of the previous villa, specifically structures 2, 5, 12 and 13, and therefore there are two superimposed thermal complexes (

Figure 14). This hypothesis includes the

natatio 3 within these elements, where there would also be a

hypocaustum below some archaeological elements at a much lower level than the second one, something we have been able to verify given that several pools are found in a profile approximately one meter below those of the second thermal complex. We also verified that the direction of the two generations of bath complex has slightly rotated directions from each other.

We can discuss the water inlet in the villa. Undoubtedly, due to the appearance of the aqueduct referred to in

Figure 5, this can be the main source coming from nearby springs. However, the continuation of this aqueduct up to the second

balneum must be questioned, given that the roof of the aqueduct is at altitude 180.10 m and 179.80 m, i.e., with a difference in height of 30 cm at the two points where we have been able to document it. Bearing in mind the height of this type of vault-shaped aqueduct, it is possible that the water circulated at altitude 179.50 m, with the hydraulic elements of the

balneum at 179.70 m at the lowest point and 180.40 m at the highest point. It is unlikely that the water was distributed from these elements, especially since the access to the water for the northernmost

natatio, which is well preserved, is at 180.30 m. Moreover,

natatio 3 is right in the middle of the conduction, the bottom of which is at 179.30 m, i.e., it is impossible for the aqueduct to pass under this pool. It could go around it, but we have found no traces of this hydraulic element in the prospections planned precisely for this purpose.

With these considerations, we can suggest that the aqueduct found at the outside part of the villa [

19] can correspond to the first phase of the villa, or at least can be related to the ancient

balneum, and to

natationes 2 and 12, which were partially divided by the second and more recent bath complex and

hypocastum, which has not been excavated.

Natatio 3 must necessarily be later and possibly contemporary with the second, as it seems to cut off the access to water from the oldest

balneum.

Other elements remain, such as the structures 5 and 13, which correspond to small cisterns or natatio, which, due to their orientation, could be related to the first phase of the villa. However, these are located at altitude 180.50 m and 181.60 m, making it impossible to have been supplied from the aqueduct. These elements have a series of conduits, with unknown direction, but which are not in line with the second balneum. Our interpretation suggests that there are three construction phases at the site. The first balneum with aqueduct, several pools and a partially preserved hypocaustum. The second bath complex, that is currently preserved was built on top of the first. Finally, in a post stage, for which we have no chronology, the water access from the balneum was reused to supply these other constructions, possibly for uses other than recreation. This hypothesis is based on the impossibility of supplying water to these hydraulic elements from any of the spaces.

About the origin of the water for the second phase of the villa, we consider feasible that the main aqueduct had a branch that supplied water to the villa in the northwest corner since otherwise there would have to be another element that we have not detect or was not preserved. This water deviation can be in a cistern that serves to redirect water to the second term on a higher level. In the future, this hypothesis may be confirmed by the continuation of the geophysical surveys, directed to certain areas based on the results of this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; methodology, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; software, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; validation, R.J.O., P.T.F., B.C., J.F.B. and A.C.; formal analysis, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; investigation, R.J.O., P.T.F., B.C., J.F.B. and A.C.; resources, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; data curation, R.J.O., P.T.F., B.C., J.F.B. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.O. and P.T.F.; writing—review and editing, R.J.O., P.T.F., B.C., J.F.B. and A.C.; visualization, R.J.O., P.T.F., B.C., J.F.B. and A.C.; supervision, R.J.O. and P.T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.