1. Introduction

Food security and food sovereignty both play pivotal roles in the development of a sustainable country that provides equality for its people [

1]. The current global population is 7.7 billion, with a projected increase to 11.2 billion by the end of the century [

2]. To achieve security and sovereignty for the expanding global community, we must strengthen our agricultural skills and efficiency [

3]. Colombia is a country located in South America within the Western hemisphere with a population estimated to be 50 million, many of whom have endured more than 60 years of armed conflict that resulted in forced displacement [

4]. According to the United Nations, Colombia has more than 78.9 thousand newly Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from January to June of 2022 [

5] However, the country's total IDP population represents 19% of the entire world’s IDP population and it is estimated that 92% of the country’s IDPs are in rural areas [

5]. This type of mass eviction results from armed organizations like guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug traffickers, and rival factions acquiring territories [

6]. Due to this circumstance, there are now massive differences between urban centers and rural settlements, which are frequently apparent [

7]. In 2020, rural areas showed that 37.1% of the people were impoverished, while in municipal capitals that number fell to 12.5%, showing that the poverty gaps are significantly increased in rural areas when compared to municipal capitals [

8]. One of the factors that influence this knowledge gap is the absence of rural education and, in many cases, illiteracy in remote populations [

9]. The difference in educational opportunities between municipal capitals and rural areas can give us insight into the vast developmental differences when comparing these two areas [

10,

11]. Cattle farming is a key tool for enhancing national sovereignty and global food security. As the global population increases, the demand for cattle products created with sustainable and effective procedures rises [

1,

12]. On the other hand, cow products account for 37% of the world's protein supply and 18% of the world's total food energy consumption for people [

12].

Cattle production in Colombia has become an important economic resource, with the total population of cattle reaching 28 million. This field represents 3% of the total GDP, 26% of the agricultural GDP, and 60% of the livestock GDP [

13]. Artificial Insemination (AI) can increase cattle productivity by promoting genetic improvement, decreasing maintenance costs for a bull, decreasing sexually transmitted diseases, and enhancing the rural economy [

14,

15]. AI in cattle consists of depositing a small amount of semen from a genetically superior bull into a female that is close to ovulation, to seek a viable pregnancy [

16]. However, to make AI a beneficial tool, there needs to be education and training supplied that outlines the benefits of this technique, when it is used correctly [

17]. It is important to identify the appropriate and beneficial genotype to introduce into your livestock, based on the final product the producer is seeking, to optimize AI as a technique [

18].

A solution for rural communities to improve education quality, opportunities, and family economics is provided by educators who share their knowledge in agribusiness, rural leadership, artificial insemination, and genetic enhancement. In Colombia, the main challenges in bovine agribusiness are not only to increase inventory and productivity, but also to improve the application of science, technology, and innovation which promotes the optimization of production and the implementation of an eco-sustainable approach [

19,

20,

21]. Introducing education in rural and impoverished communities allows closing of gaps between rural populations and those of municipal capitals. However, to achieve these goals, we must focus on the agriculture sector and invest time, training, and government funds for research, and social innovation, so that we can continue to increase production alongside the the increasing human population [

3].

It's essential to recognize the untapped workforce that consists of rural leaders and undergraduate students. When attempting to improve the circumstances, possibilities, and standard of living of farmers in rural areas, our research has found this untapped potential to be a tremendous benefit. They are an asset to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations in 2020, in the areas of quality education, decent work and economic growth, reduced inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, responsible production, and partnerships for the goals [

22]. With this kind of partnership and extension work, we can move closer to achieving at least 6 of the 17 SDGs [

23]. Only with true leadership can we place agriculture in the position it deserves and obtain the conditions and opportunities to generate wealth from rural areas, improve the standard of living in our societies, reduce poverty and migration from the countryside to cities, increase investment, credit, research, extension and generate an environment of trust in rural areas [

24]. Our goal was to determine the effects of a theoretical-practical training program in rural management and leadership, artificial insemination, and bovine genetic improvement, on the perception and level of knowledge of a rural population affected by the Colombian armed conflict.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of the sample and study area

Considering the social implications of this study, the selection of the beneficiaries included people who met the following criteria: 1) admitted to being victims of the armed conflict; 2) lived outside of municipal capitals and major towns; 3) had a rural occupation producing cattle; and 4) lived in areas with little to no state presence in Colombia.

2.2. Training and selection of the student leaders

The initial phase for selection included the practical and theoretical training of undergraduate animal science students and was performed during 6 theoretical conferences, which lasted for 45 minutes each session. The training was focused on leadership and rural communication, bovine agribusiness, female bovine reproductive anatomy, artificial insemination, and genetic improvement in bovines. These topics were offered by professors with doctoral degrees and expertise in their respective fields. Subsequently, a 36-hour practical session was held at an animal production center that had a dual-purpose bovine production system. The practical activities were developed in focal groups as follows:

Group 1. Agribusiness and leadership: a collective discussion on the basic principles of rural management, agricultural extension methodologies, leadership, and social innovation.

Group 2. Anatomy of the female bovine reproductive system: visualization of parts of the reproductive system in the bovine female supported by real anatomical pieces and the book Reproduction of the cow: didactic manual on the reproduction, gestation, lactation, and well-being of the bovine female by [

25].

Group 3. Blind identification: blind palpation of objects using different structures, consistencies, and sizes.

Group 4. Insemination technique and catheter placement in anatomical pieces: assembly of the artificial insemination gun and blind access to the uterine body through the cervix of a real anatomical specimen.

Group 5. Management of semen and liquid nitrogen tanks: basic concepts for the management, care, and maintenance of the liquid nitrogen tank and the semen stored there.

Group 6. Rectal palpation of cows: once the students passed the assigned tests in each group, they performed rectal palpation and identified the cervix as one of the initial steps for artificial insemination.

For the selection of student leaders, at the end of the theoretical and practical sessions, a knowledge test consisting of 25 multiple-choice questions with a single answer was applied. Additionally, during the practical day, each student was given a behavioral test that sought to identify their skills, characteristics, solidarity skills, and their social sensitivity. During these tests, behaviors that were aimed at motivating, inspiring, and positively influencing their peers during the development of practical activities were recorded. Once the training was completed, a consolidation of the applied tests (knowledge and behavioral) was carried out. The criteria for the selection of the students were: to obtain correct results in the tests (theoretical and practical) on at least 90% of the questions, pass the behavior test and show interest in participating in the next phase of the project. The students selected in this phase were called student leaders.

2.3. Socioeconomic characterization and training of rural residents

Before the commencement of training for participating rural residents, they were asked for information on their various socioeconomic realities. This included family composition, level of schooling completed, possession of land and animals, productive vocation, and economic standing. The training of the participating rural residents was carried out according to the same protocol that was used for the training of the student leaders.

2.4. Measurement of knowledge for rural residents

To measure participants' perception of knowledge (subjective evaluation), the participating rural residents completed a knowledge perception survey, which had a 5-option Likert-type ordinal scale including the following: (1) Definitely not, (2) Probably not, (3) Undecided, (4) Probably yes, and (5) Definitely yes. The topics evaluated were grouped into two dimensions: rural management and leadership, and artificial insemination and genetic improvement.

For the objective evaluation of knowledge, the participating rural inhabitants were evaluated individually with a test of 8 multiple-choice questions with a single answer, grouped into 3 dimensions: rural management and leadership (D-ML), artificial insemination in bovines (D-AI), and genetic improvement (D-GI). Additionally, the grouping of the three dimensions was considered for the evaluation of general knowledge (GTD). The test was applied before the start of the training (pre-test) and upon completion (post-test). The qualification was categorized in a nominal dichotomous way and recorded as successful (1) or not successful (0). This analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of theoretical and practical training on the appropriation of knowledge related to agribusiness and artificial insemination in cattle.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data were presented as means ± SEM for statistical analysis using SAS® (version 9.2, SAS Institute). The normality of the variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p>0.05); meanwhile, the intra-subject comparisons used the Wilcoxon test, and for the correlation of variables the Spearman's r test (p<0.05). The reliability or internal consistency of the instrument used to assess the perception of knowledge was confirmed by the Cronbach's Alpha model test (α≥0.7), given the ordinal scale due to the nature of the data. The reliability or internal consistency of the instrument used to assess the levels of knowledge given the dichotomous nature of the data (1=correct, 0=not correct), was evaluated using Richarson's Kuder method (KR21) taking as reference a value of α ≥ 0.7. The validity of the instruments applied to measure knowledge was determined by the group of experts who were part of the study.

3. Result

3.1. Selection of the study area

Following the selection criteria, the geographical areas selected to benefit were two municipalities located in the department of Nariño, which is in the south of Colombia. The first municipality selected was “Los Andes Sotomayor”, which is 1,570 meters above sea level, with a population of 9,791 inhabitants, with 4,200 inhabitants located in the municipal capital and 5,591 inhabitants located in rural areas. The second municipality selected was “La Llanada”, which is 2,300 meters above sea level, with a population of 5,321 inhabitants, with 2,822 inhabitants located in the municipal capital and 2,499 inhabitants located in rural areas. Both municipalities met the requirements of having a history of armed conflict, having access roads in poor condition, and were located more than 8 hours from the capital of the department of Nariño (Pasto). Additionally, the selected municipalities have a high livestock vocation oriented to the production of milk, meat, and dual purpose. In addition, the illegal armed group identified as the "National Liberation Army" (ELN) is present in both municipalities.

3.2. Training and selection of student leaders

Out of the 70 students trained, 60% identified as female and 40% as male, 34% of the participating students belong to a socioeconomic status level of 1, 46% to level 2, and 20% to level 3 (socioeconomic status levels are ranged from 0 to 5). Additionally, 63% of the students came from peri-urban or rural areas. Of the total number of participants, 52 (82%) attended the practical day in the field (

Table 1).

Out of 52 students who attended the practical session, 13 were selected, based on compliance with the guidelines described above in the knowledge and behavioral tests, as well as expressed their interest in continuing in the transfer process of technology to rural people. These students formed what we call the "group of student leaders" who would later train rural residents.

3.3. Socioeconomic characterization and training of rural inhabitants

The training included 63 participants, with an average age of 42 years, of which 71% declared to have been victims of the armed conflict. The participants were considered small producers, who had on average herds of 4 producing cows and 14 hectares of land [

26]. Regarding education level, 40% of the beneficiaries had primary education, 46% completed secondary school, 2% carried out technical or technological studies, and 12% had professional studies (see

table 2).

Households were mostly made up of a mother, father, and children (62%), 25% were single, while 7% and 6% were fathers and mothers who were heads of households, respectively. Livestock farming represented the main source of income for 61% of project beneficiaries, followed by crop production (20%), mining (6%), and off-farm work activity (4%), while 9% recorded that they devoted themselves to other activities such as a student or a housewife.

3.4. Measurement of knowledge of rural inhabitants

The perception of the knowledge of the participating rural residents was relatively low (2.48±0.76) compared to the three dimensions evaluated. The perception of knowledge in the D-ML was higher, without being good (2.89±1.18), on the other hand, the perception for the D-AI and the D-GI were lower compared to the previous one (2.17 ±0.83). The instrument used for the measurement presented reliability in Cronbach's alpha model of 0.78, which represents good reliability of the questions used in this tool. The consistency or degree of confidence of the knowledge evaluation through the written test was validated by applying Richarson's Kuder method (KR21), obtaining a value of 0.83, indicating that this evaluative instrument is likely to be applied in future projects that seek to diagnose the state of knowledge in the three dimensions evaluated in a rural population. Initially, an intra-subject comparison was performed between the results of the pre-test and the post-test after the intervention, for which the normality criteria were initially determined from the Shapiro-Wilk test of the dimensions evaluated (D-ML, D-AI and D-GI, and GTD) finding that all presented a non-normal distribution (p˂0.05).

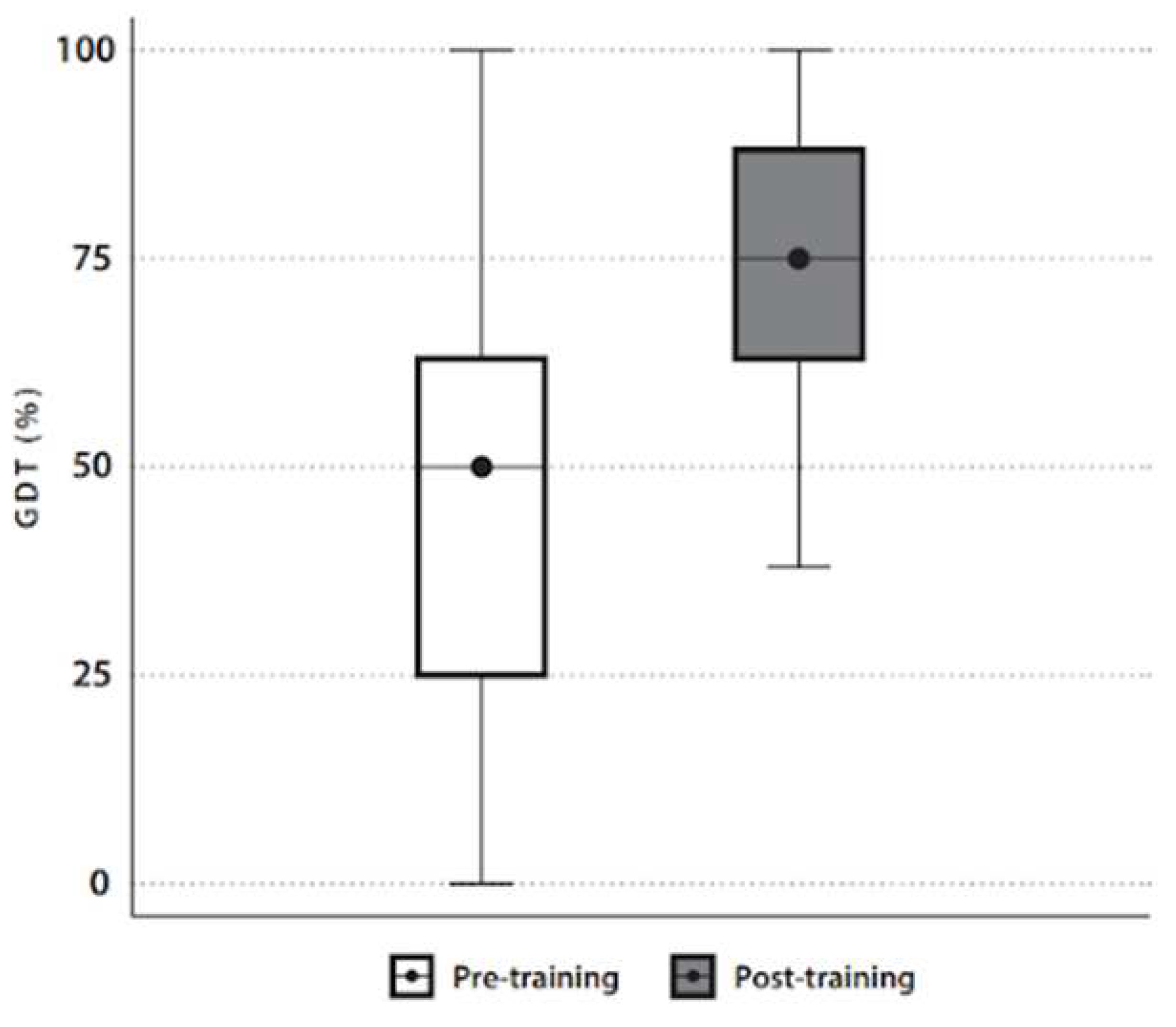

Subsequently, compliance with the study hypotheses (H0:MeO1=MeO2; H1:MeO1≠MeO2) was determined using a non-parametric test (Wilcoxon test, α<0.05) derived from the analysis of the distribution of the variables to be contrasted. It was established that the training of the participating rural leaders had positive and statistically significant effects (p<0.01) (

Table 3) on GTD. The median value in the pre-test went from 4.0 (RI=3.0) to 6.0 (RI=2.0). The level of knowledge in each theme was measured by the number of correctly correct answers by each participant and later this number was expressed as a percentage (%). The level of general knowledge in the three dimensions evaluated before starting the training was 45.9%. However, once the training day was over, this value increased to 77.6%, showing a net increase of 31.7% (p<0.01). On the other hand, it was possible to determine that the size of the effect of the intervention was large (d>0.80) and its statistical power (1-β=1.0) very high, indicating an improvement in knowledge and knowledge in all the subjects who did part of the training (

Figure 1).

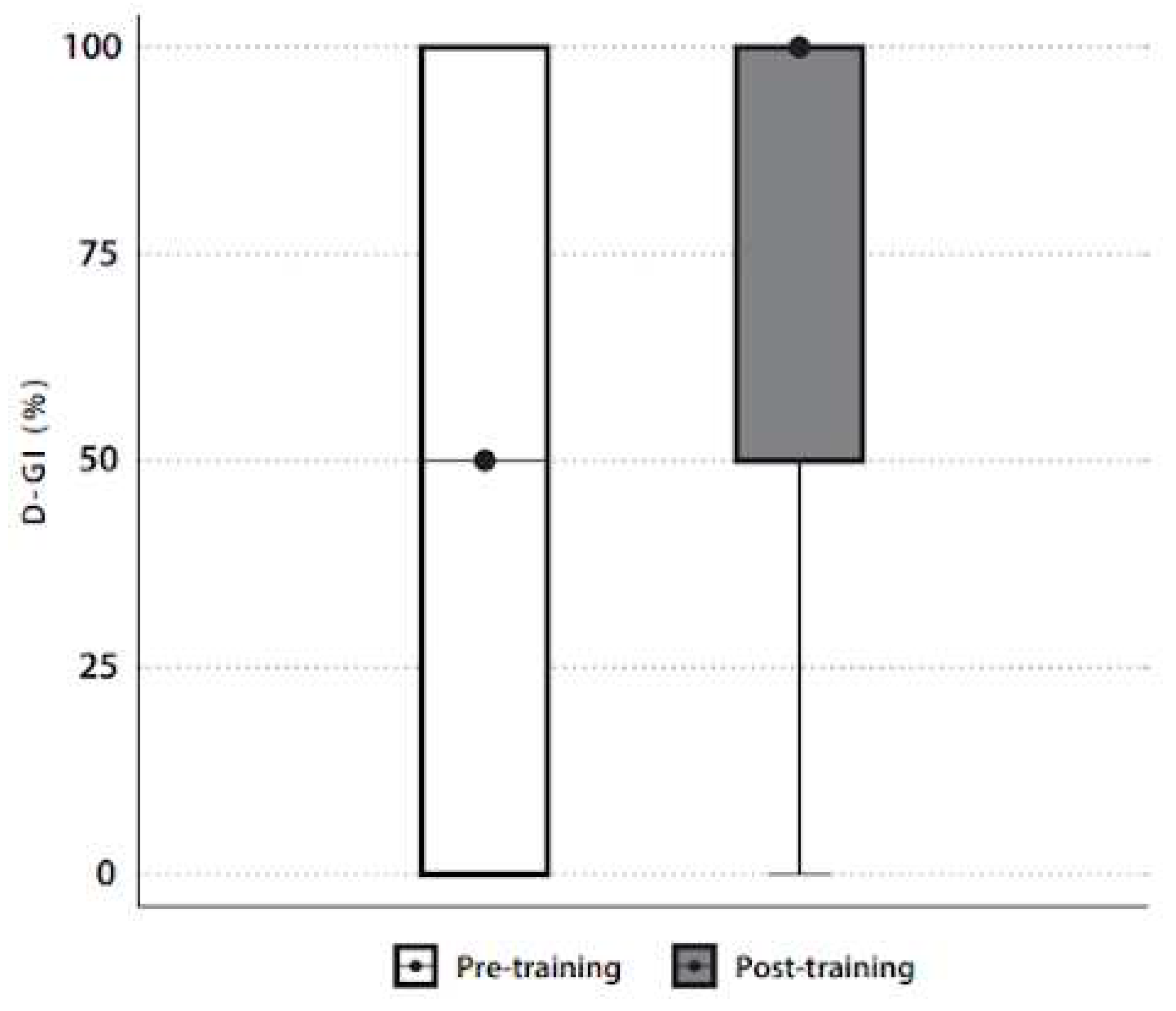

In the analysis by dimensions, the one referring to D-AI (

Table 3), also presented statistically significant changes (p<0.01), and high effect size and statistical power (d>0.80; 1-β=1.0) (

Figure 2). The level of knowledge related to the D-AI showed 38.5% before the start of the training and 80.6% at the end of the day (p<0.01). These results showed an increase of 42.1% after the intervention.

The level of knowledge in the D-GI went from 50.8% to 73.0% before and after the training, generating a change of 22.2% (p<0.01) attributable to the teaching day. This dimension presented a medium effect size (d=0.50) and a high statistical power (1-β=0.89) (

Figure 3).

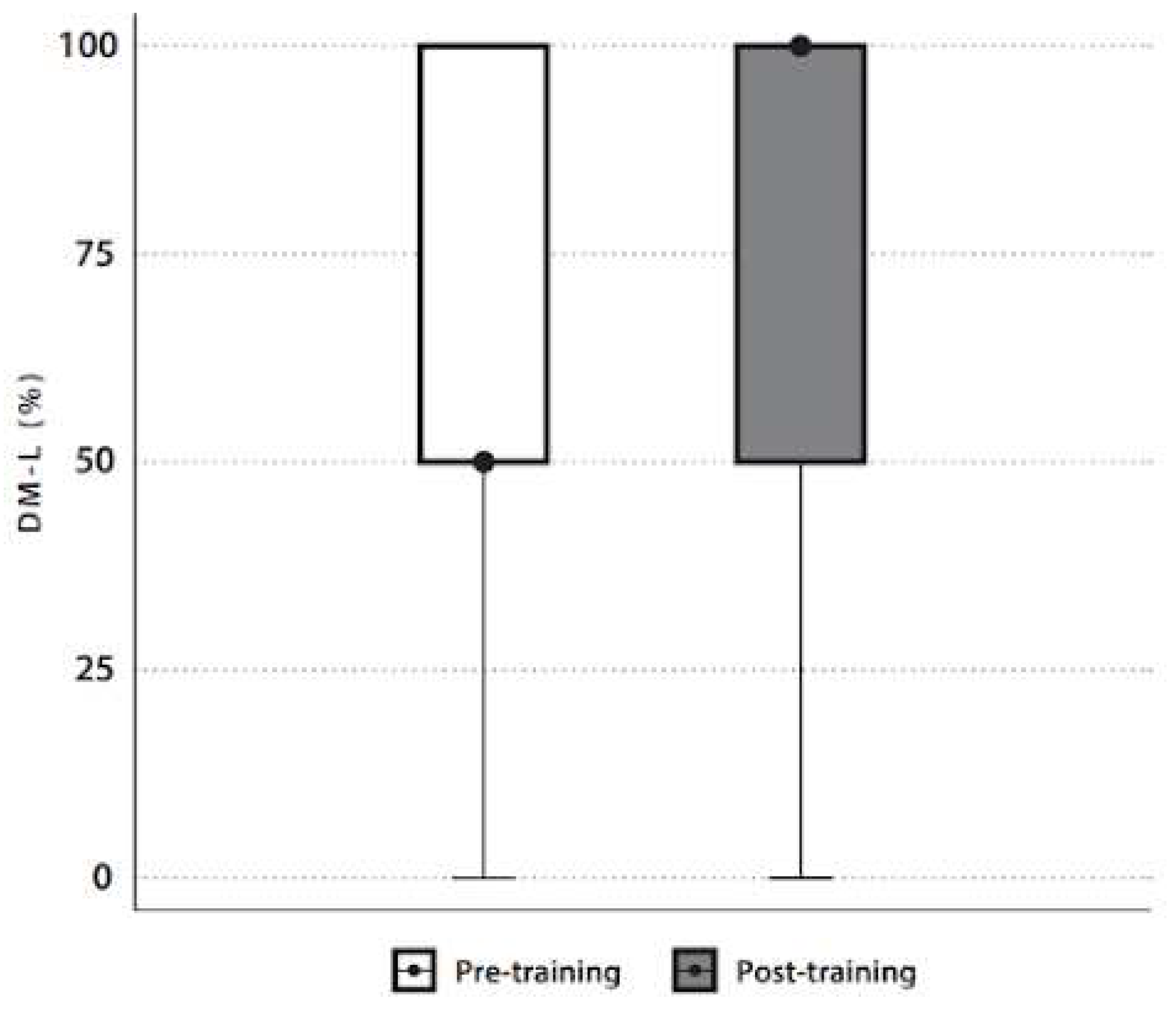

Finally, the level of knowledge related to the D-ML was evidenced 54.8% before the start of the training session and 75% at the end; an improvement of 20.6% with a significant difference (p<0.01) before and after training (

Table 3). The effect size (d=0.45) was in a small assessment and its statistical power was high (1-β=0.80) (

Figure 4).

On the other hand, a low but statistically significant positive correlation was found (rs=0.306; p<0.05; R2=0.094; w=0,30; 1-β=0.68) between the subjective perception of knowledge versus objective knowledge of each rural population evaluated before the intervention, with a medium effect size (w=0.3) and a barely acceptable statistical power (1-β=0.68).

4. Discussion

More than 70% of the rural participants in the survey recognized as victims of the armed conflict in Colombia, demonstrating the vulnerability of this group. This is in line with a global trend that has witnessed a 1.6-fold increase in forced evictions over the past ten years, from 43.3 million in 2009 to 70.8 million in 2018. Colombia has 8 million people who were forcibly displaced, representing 15% of the country’s total population and 11.2% of the world’s total displaced population. These figures show that second only to Syria, Colombia has the largest population affected by displacement in the world [

27]. For more than 60 years, Colombia has faced an intense and violent armed conflict between the State and illegal groups, many of them labeled as revolutionary guerrilla groups [

4]. As a result of the armed conflict and exacerbated by the policies of a centralized government with a low presence in some rural geographic areas of the country, it is estimated that more than 90% of the total displaced population in Colombia is of rural or semi-rural origin. This affects Colombia’s agricultural productive capacity, hinders access to education and disintegrates the family nucleus of rural inhabitants [

28,

29,

30]. Interestingly, the evaluated rural population had a low level of schooling, with only 86% having completed basic primary and/or secondary education. The theory of Maximum Maintained Inequity affirms that the increase in educational coverage in a country or territory reduces the social and economic inequalities of a society [

31,

32,

33]. These results suggest that the two geographical regions of interest do not have an optimal presence of the Colombian state that could guarantee education, electricity, drinking water, and health, among other aspects of vital importance. Due to the scarce technical and professional support, livestock production in the selected areas were small and lacking in technology, even though this is vital for family economics in theses territories affected by violence.

On the other hand, mining has social, economic, and environmental effects that affect populations depending on the degree of legality. There are many types of mining found in Colombia, such as formal, informal, legal, and illegal mining, the latter being generally influenced or controlled by armed groups outside the law [

34]. Interestingly, livestock, agriculture and informal and illegal mining were represented as some of the most important economic activities for the residents participating in the training. [

34] reported a direct correlation between illegal mining and multidimensional poverty amongst rural populations in Colombia. These findings suggest that this type of illegal activity is strengthened when there is a weak state presence in these regions, where illegal armed groups have an advantage [

4].

Agricultural literacy is based on the fact that each person must have a minimum level of knowledge on how industries produce and process the food necessary for human survival. This concept becomes more important for people who participate in the productive chains of the agricultural sector or study a related career, since they have a level of empirical, technical, or professional knowledge which is transmitted in each generation [

35]. A strategy to strengthen agricultural literacy is through the incorporation of undergraduate students who have a high degree of commitment, sensitivity, and leadership to extension projects, considering this initiative as part of social innovation [

36,

37]. Social innovation assists in problem solving in a society to enable the inhabitants to improve on their living conditions for generating projects and initiatives that include social or human potential [

38]. Considering the above information, universities play unique and important roles, becoming key instruments for social transformation, through the implementation of outreach activities that promote and enhance relationships between teachers and students so that the students can become transforming engents of education in a society [

39]. The unique qualities and abilities of each student should be identified and encouraged, to subsequently be used as strategies as part of a solution to social problems in vulnerable communities [

40].

According to the analysis performed by dimensions, it is possible to infer that the training had a positive effect on the rural inhabitants, making it an important tool to strengthen human capital and improve productive skills and the ability to process information of the rural population [

41]. In the case of D-AI, statistically significant changes, high effect size and statistical power were obtained, indicating that in this component it is possible to infer a positive effect in the investigated subjects. In the D-GI, although the effect size was medium, there was a statistically significant difference between the pre-test and the post-test after the intervention and a very good statistical power, which indicates that it is unlikely (11%) to commit a type 2 error if the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, it can be inferred that the intervention process was successful in terms of the acquisition of knowledge related to genetic improvement in the intervened group. Finally, the level of knowledge related to the D-ML suggests an improvement with a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test, and a small effect size with a high statistical power; which implies that the knowledge related to rural management and leadership were successful, although the probability of being wrong when rejecting the null hypothesis is at the limit of what is allowed (20%), so for future interventions, it is suggested to implement strategies of didactic order that allow a greater appropriation of this theme in subjects with similar characteristics.

The correlation analysis of the values obtained in the subjective perception of knowledge compared to the objective knowledge of each evaluated rural population; indicates that those who have a low perception of knowledge show an equally low score in the objective test of knowledge. However, the statistical findings show that although the perception of the study participants tends to be closer to their levels of knowledge, this is not the same across the group, so using the instrument on the objective knowledge that was used to evaluate the three dimensions becomes more appropriate to effectively determine their knowledge and level of appropriation in the intervention topics.

Up to the date of writing this work, this is the first report of evaluation of knowledge before and after a day of practical theoretical training led by undergraduate students to rural residents affected by an armed conflict. However, Fekata and colleagues in 2020 [

17] evaluated the perception of estrous synchronization and artificial insemination in cows in 122 rural residents, who showed low credibility and perception in relation to these two techniques. Interestingly, the authors propose to evaluate for future studies the knowledge of producers in estrous synchronization and insemination and conclude that increasing the degree of knowledge and training of the participants would favor technological adoption and positive perception towards these two techniques. We discovered that the rural participants in this study believed their knowledge in these areas to be limited when assessing their sense of expertise in the topics reviewed before the training. This result was obtained after a previous statistical validation of the reliability of the instrument used to measure the perception of knowledge and coincides with some of the findings described by [

35]. In this study, Frick et. al. compared the degree of perception of knowledge of agriculture between 456 rural inhabitants and 428 urban inhabitants. Although both groups showed an acceptable perception of knowledge in aspects related to animals and crops, the study shows that the level of education of the participants influenced the number of correct answers obtained, thus concluding that the respondents with higher levels of education perceived their knowledge better than knowledge compared to those with less education, which coincides with the low level of schooling of the largest proportion of the participants in this study and their perception of the knowledge evaluated [

35]. This reaffirms the importance of increasing educational coverage for populations affected by the armed conflict. The primary goal of rural extension is to enable extension agents to effectively impart information to rural producers, enabling them to make better decisions and adopt productive practises that enhance their living situations [

41,

42].

Although the effect of teaching and learning on artificial insemination in cows has not been evaluated in rural populations affected by the armed conflict, Dalton and colleagues in 2021 designed an extension program to facilitate the appropriation of knowledge and practical skills related to artificial insemination in students studying veterinary medicine [

43]. This study allows us to conclude that, through a 2-day training, involving 8 hours of theoretical instruction and 8 hours of practical activities, the students developed effective skills that allowed them to pass the knowledge tests applied in the experiment. Therefore, it is important to implement new didactic strategies for teaching programs that improve the quality of life of students and rural residents [

44,

45]. Given that the intention of the present study was to evaluate the effect of practical theoretical training in knowledge skills (management and leadership, artificial insemination, and genetic improvement) in rural residents who are victims of the Colombian armed conflict, a measurement instrument was designed that would allow assessing the essential elements learned by the participants during the training day. Interestingly, the level of general knowledge in the participants, which included theoretical elements of each of the topics offered, increased with a high degree of effect size after the completion of the training day. Due to the above and as it is well reported in several studies, extension not only becomes an instrument to innovate, create, and enhance teaching and learning processes, but also to reduce social and economic gaps [

45,

46]. Since the main economic activity of the participants was livestock, the instrument was designed to assess the knowledge included rural management and leadership, artificial insemination, and genetic improvement in cattle. When evaluated after the completion of the study, the training was found to result in substantial improvements in these areas. The above results have a greater social value, since the training of rural residents was carried out under the leadership of the students as a strategy of social innovation for the improvement of the productive conditions of the participants. These strategies have been used in other fields such as architecture, where universities assume an essential role in closing the gaps between urban and rural life [

36,

37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Amy Montgomery; Data curation, Yasser Lenis, Amy Montgomery, Enoc González-Palacio., Dursun Barrios. and Mohammed Elmetwally; Formal analysis, Yasser Lenis, Diego F Carrillo-González and Mohammed Elmetwally; Funding acquisition, Yasser Lenis; Investigation, Amy Montgomery; Methodology, Yasser Lenis, Diego F Carrillo-González and Enoc González-Palacio.; Project administration, Yasser Lenis; Resources, Yasser Lenis; Software, Diego F Carrillo-González and Dursun Barrios.; Supervision, Yasser Lenis; Validation, Amy Montgomery and Enoc González-Palacio.; Writing – original draft, Yasser Lenis, Amy Montgomery, Diego F Carrillo-González, Enoc González-Palacio. and Dursun Barrios.; Writing – review & editing, Yasser Lenis, Amy Montgomery, Diego F Carrillo-González, Enoc González-Palacio. and Dursun Barrios