1. Introduction

Diabetes treatments like metformin affect the risk and the incidence of breast cancer [

1]. Metformin is an oral, hypoglycemic, biguanide used mainly to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D). Evidence shows that metformin is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality [

2] and reduced risk of certain cancers (e.g., breast cancer) in addition to improving glycemic regulation [

1].

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that affects the lymph nodes in the armpits and other organs, starting as a local lesion in the breast and then spreading progressively. Several factors serve as alarms and decide the type of cancer, treatment and outcome [

3]. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom, they found that most ladies with type 2 diabetes who have used metformin for many years showed reduced chances of breast cancer, whilst no such impact was found in cases of temporary use. When they excluded insulin users from the assessment, the correlation was close [

4].

A systematic review done in Kazakhstan discussed the possible anticancer mechanism of metformin, and the significance of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) as an expected target for anticancer treatments [

5].

According to some articles from the Journal of Clinical Oncology of American Society of Clinical Oncology, the incidence of breast cancer in women with diabetes who were not taking metformin treatment was significantly higher than the incidence of breast cancer in women with diabetes who were receiving metformin[

6].Furthermore, a review article discussed multiple molecular properties of metformin, such as reactive oxygen species inhibition, mTORC1, as an anti-tumor agent, ADORA and activation of AMPK have indicated its benefits[

7].Additionally, a study discussed the use of different doses of metformin, i.e., 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 mM to challenge breast cancer cells (MCF-7) and colon cancer cells (CaCo-2). A substantial reduction in the cell count of both colon and breast cancer cells was revealed by the Trypan blue assay [

8].

In a study focused on determining whether metformin use can be linked to a change in the pathologic complete response (PCR) rates in diabetic patients with breast cancer after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, it was discovered that diabetic patients using metformin showed a greater PCR rate than diabetics who did not take metformin for their diabetes[

9].Moreover, in another report, which studied the ability of metformin to prevent proliferation of breast cancer cells, it was found that in vitro decreases colony formation. For breast cancer patients, ER and erbB2 are important prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. In the said study, 4 breast cancer cell lines with variable levels of expression of these two markers were used to research the effects of metformin used in vitro including: MCF-7, and MCF-7/713 (MCF-7 transfected with erbB2, BT-474 and SKBR-3)[

10].

Although there are many studies, statistics and conclusions about the role of metformin in breast cancer, a review has been conducted in various regions of Saudi Arabia, including the city of Hail, which showed that there is no relationship between breast cancer and diabetes. Thus, despite Hail having the highest percentage in diabetes mellitus, results showed the lowest percentage of breast cancer in the city [

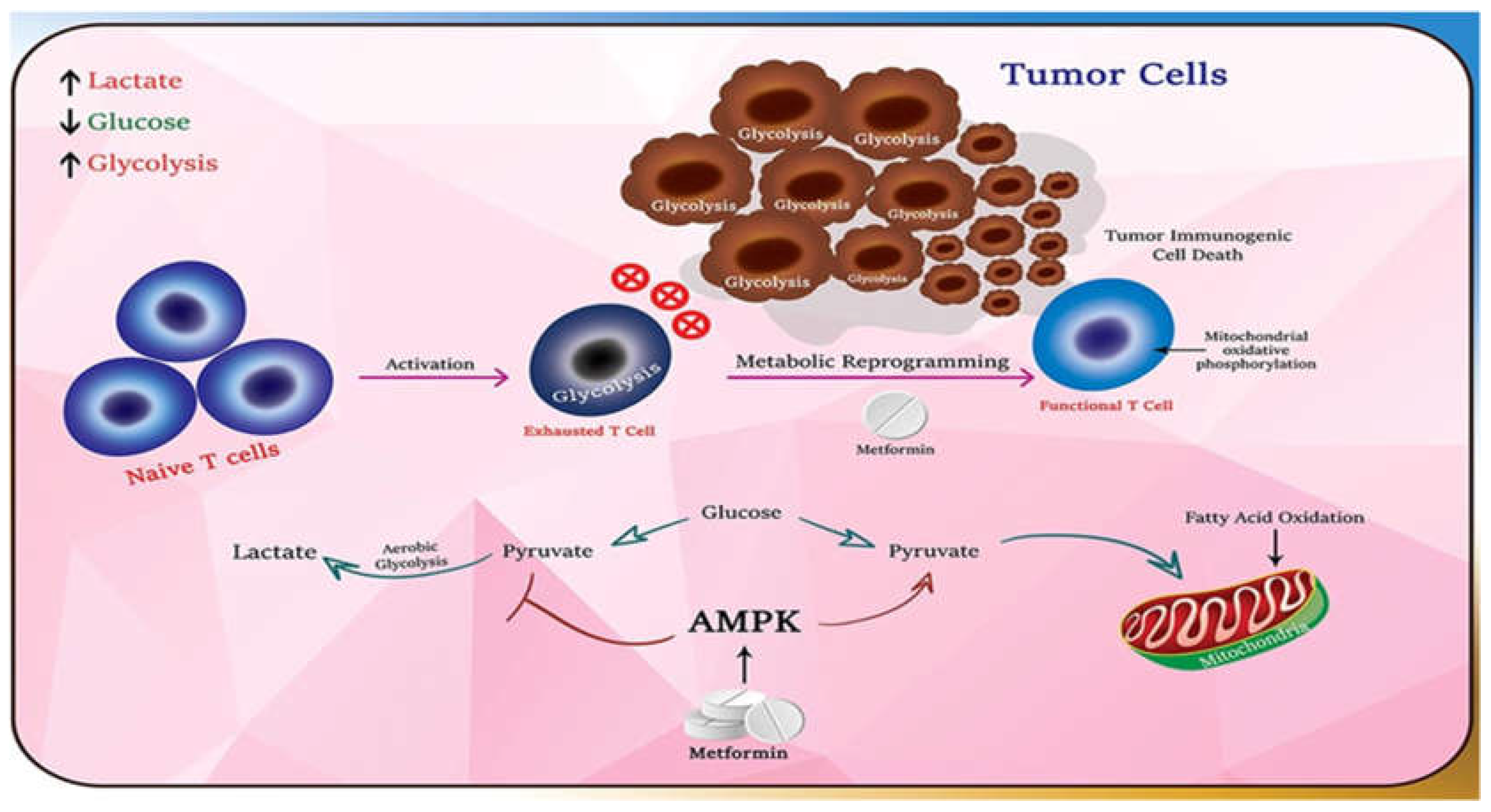

11].Metformin is believed to have positive effect on immune responses against tumor cells and metabolic pathways within cells mainly through activation of AMPK (Adenosine Monophosphate–Activated Protein Kinase)(

Figure 1) [

12]

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out among Ha’il women with type 2 diabetes using metformin with the help of direct patient interviewing in the Specialized Diabetes Center in Ha’il at King Salman, and through an online self-administrated questionnaire via. Google forms. Inclusion Women with diabetes -Individual having a family history with breast cancer. A convenient sample size (n=257) was selected. Patient enquires included enquires, such as patient’s demographic data, medication information, comorbidities condition, medication adherence, breast cancer diagnosis, family history of ovarian or breast cancer and relationship degree, type of management used for breast or ovarian cancer. The data gathered was analyzed using SPSS Version 23 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences, with endnote citations.In above result p.vlue is significant when P≤0.05[

13]. Both the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Chi-square test (X2) were used to determine the statistical significance across groups. P values under 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Demographic Data

About, 38.9% of patients aged more than55 years with 42.8% university level education, followed by 30.7% of patients aged between 46-55 years with 27.2% having primary education. About, 27.2% of patients aged between 35-45 years with 21.8% of secondary level education, and the least number of patients (3.1%) aged between 25-35 years with 8.2% intermediate education level were selected for this study (

Table 1).

3.2. Medications Information

About 98.8% of patients were using metformin for treatment of diabetes, whereas only 1.2% did not use metformin. Out of the patients using metformin, 38.6% used metformin for 5-10 years, 37% of them used metformin for less than 5 year, and 24.4% used metformin for more than 10 years. 68.1% of patients did not take any additional medication with metformin while 31.9% of patients took medication in addition to metformin. The major medications used alongside metformin were Insulin (45.1%), Linagliptin (20.7%), Sitagliptin (11%), Glimepiride (8.5%), Empagliflozin and Sitagiliptin (8.5%), Gliclazide andSitagliptin (4.9%), and Empagliflozin (1.2%) (

Table 2).

3.3. Comorbidities

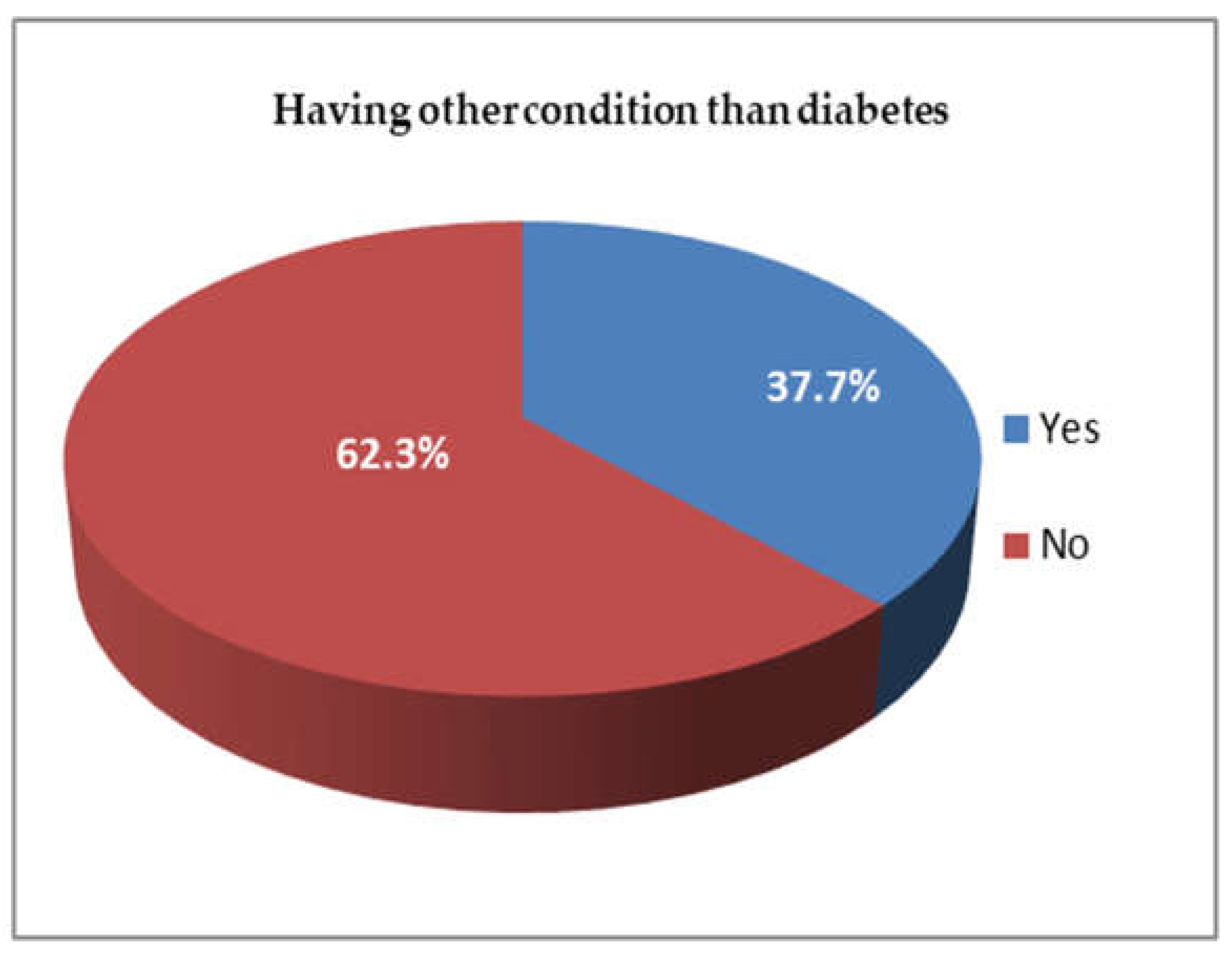

About 62.3 % of patients had comorbid disease and 37.7% did not have any other disease apart from type 2 diabetes militias (DM) (

Figure 2).

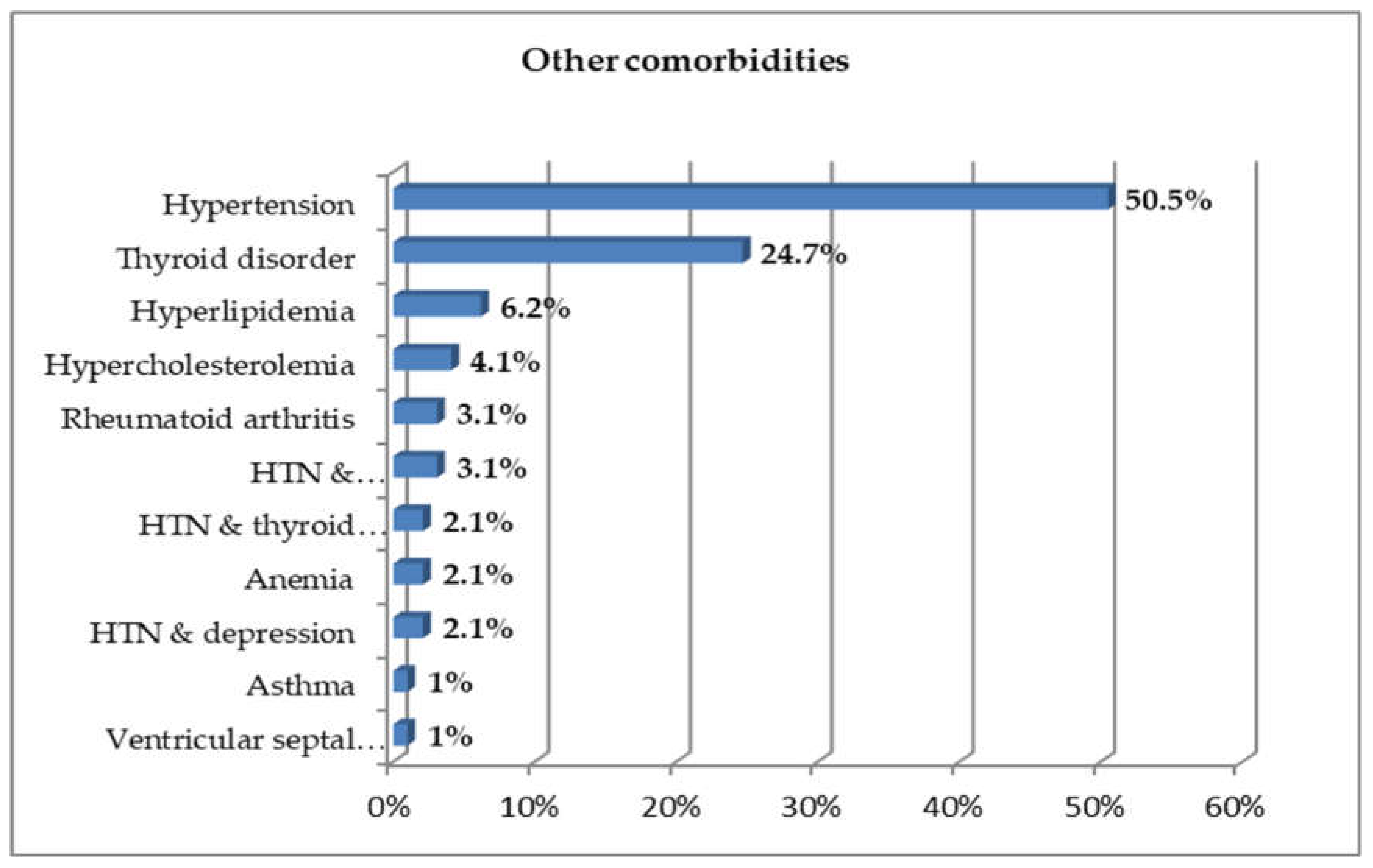

3.4. The Type of Other Comorbid Condition

Out of the all the comorbid diseases that patients were suffering from, 50.5% of patients suffered from hypertension, 24.7% from thyroid disorder, 6.2% from hyperlipidemia, 4.1% from hyperchlosteramia, 3.1% from rheumatoid arthritis, 3.1% from hypertension with hypercholstremia, 2.1% from hypertension and thyroid, 2.1% from anemia, 2.1% from hypertension with depression, 1% from asthma, and 1% from ventricular septal defect (

Figure 3).

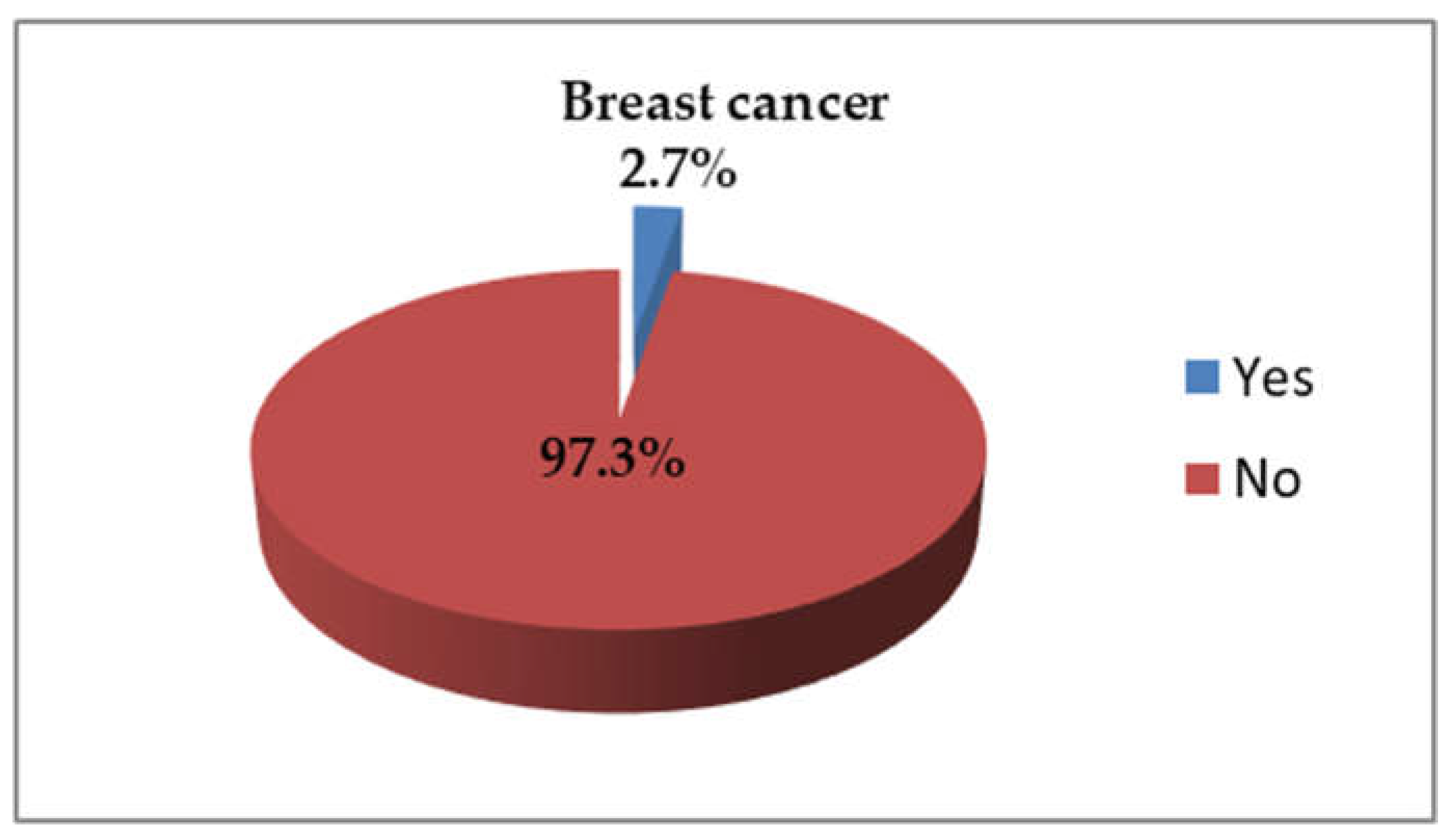

3.5. Breast Cancer Diagnosis

About 2.7% had been diagnosed with breast cancer while 97.3% did not have breast cancer (

Figure 4).

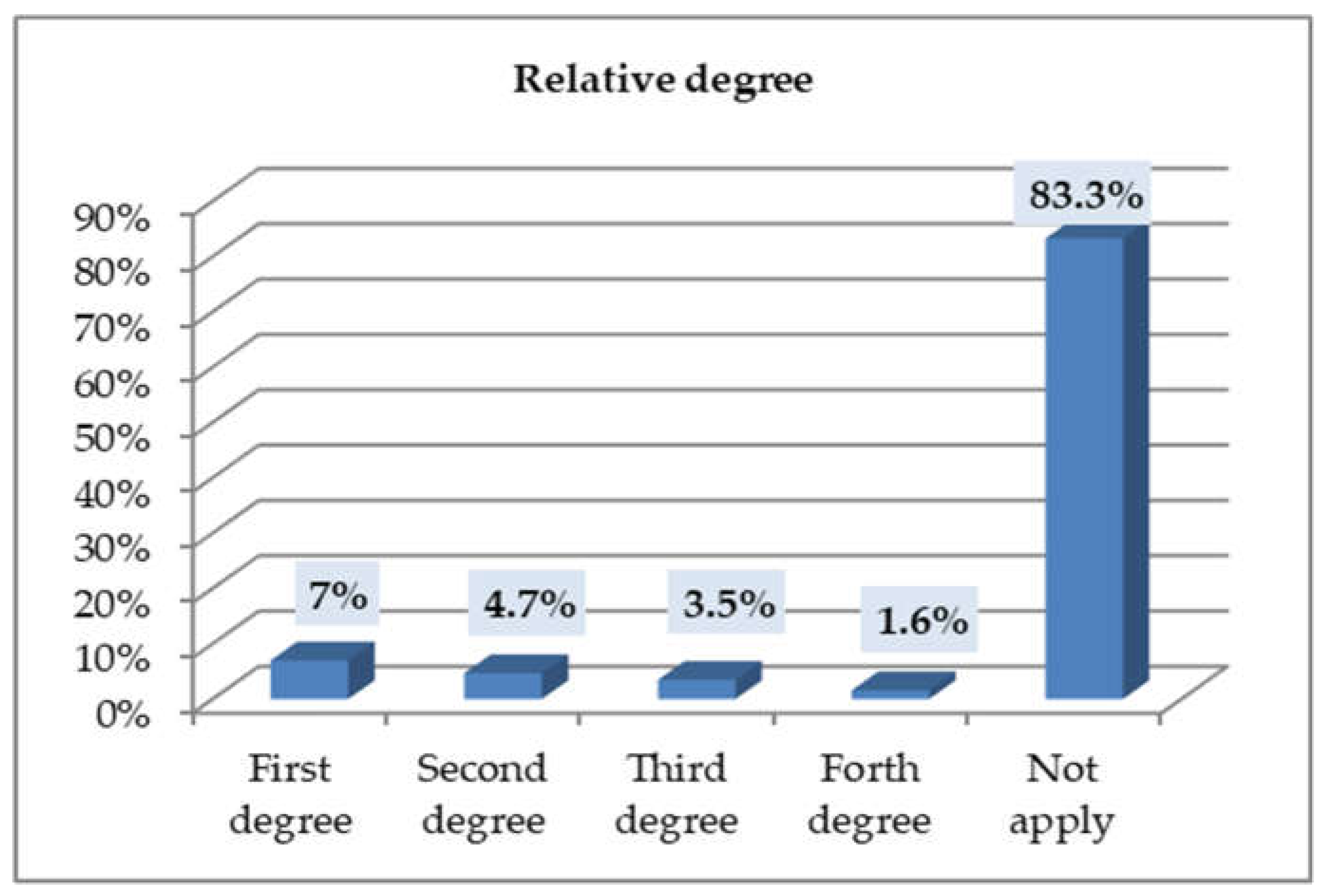

3.6. Relationship Degree (for Participants Who Had Family History of Breast or Ovarian Cancer)

First-degree relative 7%, 4.7% second-degree relative, third degree are 3.5% and 1.6% are fourth-degree relative (

Figure 5).

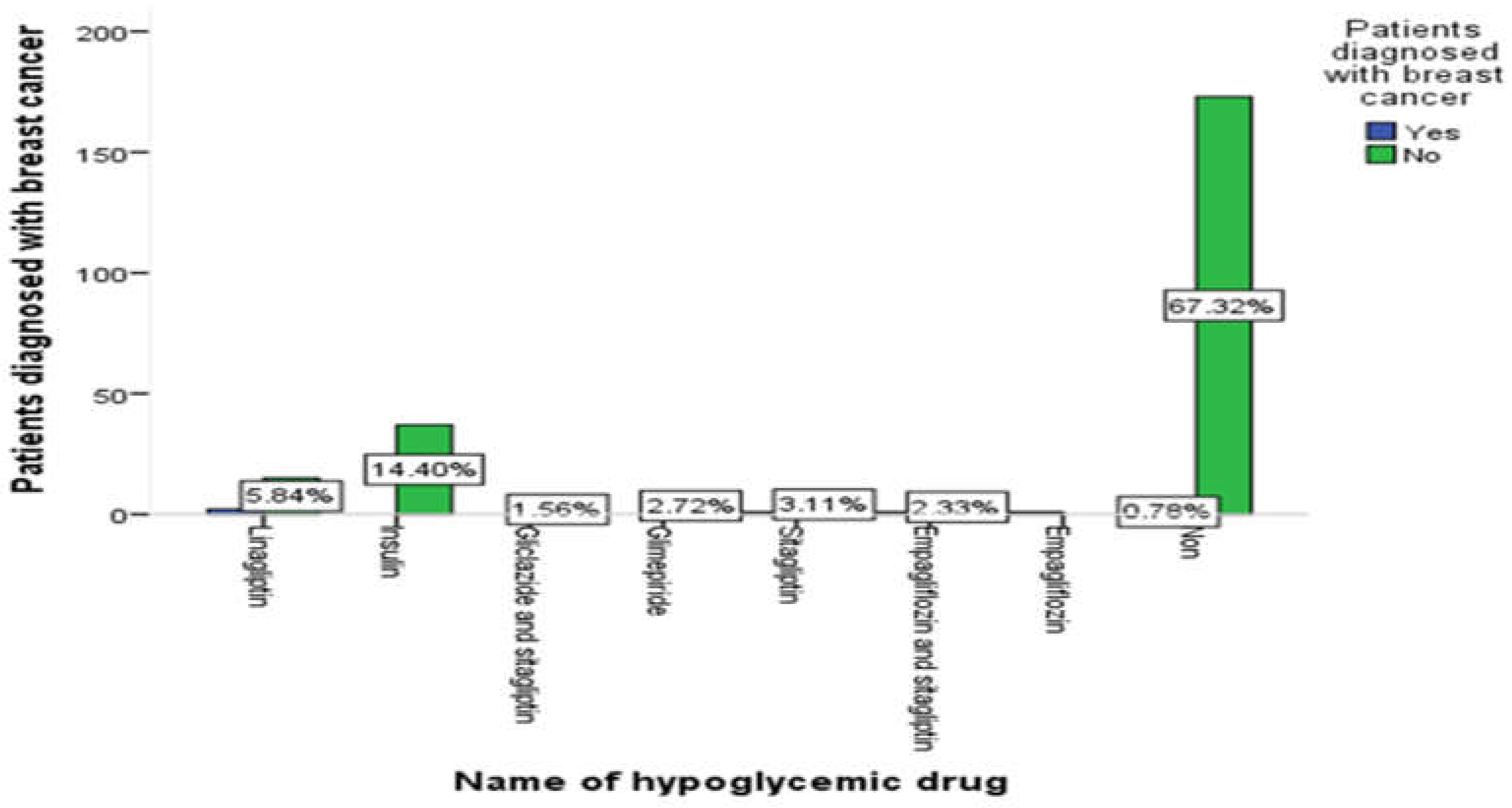

3.7. The Relationship between Medication Group and Patients Diagnosis with Breast Cancer

The majority of patients take metformin only (64.3%) or metformin with insulin (14.4%) does not suffering from breast cancer (

Figure 6).

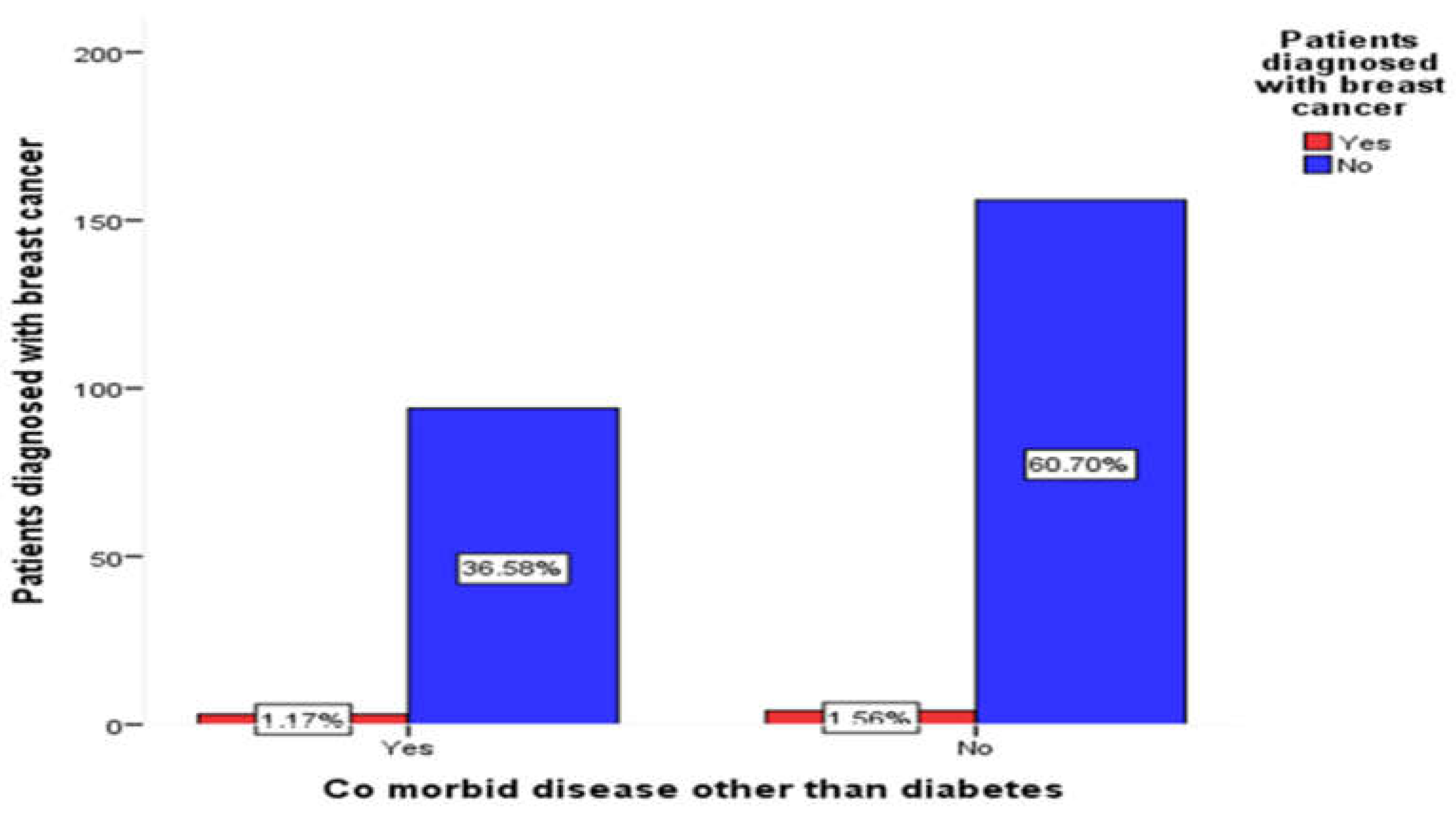

3.8. The Relationship between Co-Morbid Disease & Patients Diagnosis with Breast Cancer

The percentage of patients having no comorbid disease and diagnosed with breast cancer (1.56%i.e 57.14% of breast cancer patients) than those having comorbid disease (1.17% i.e. 42.86% of breast cancer patients) (

Figure 7).

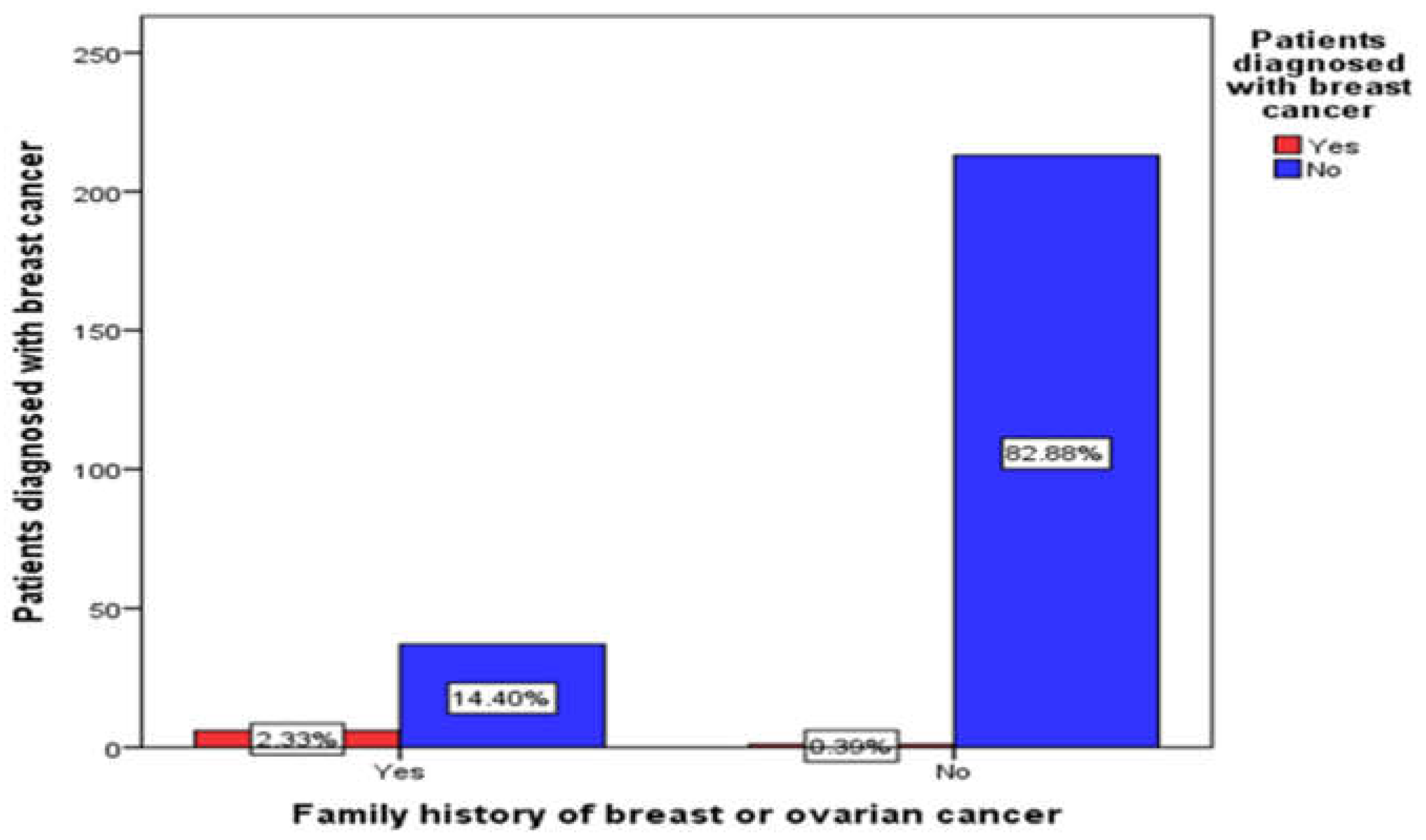

3.9. The Relationship between Medication Group and Patients Diagnosis with Breast Cancer

The percentage of patient diagnose with breast cancer that have family history of breast cancer is higher (2.33%i.e 85.35% of breast cancer patients) than those with no family history (0.39% i.e 14.29% of breast cancer patients) (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. More than 1,000,000 cases of breast cancer, and more than 380,000 deaths from breast cancer were recorded in the year 2000 [

14].Metformin the anti-diabetic agent that reduce the risk of breast cancer [

15].

A majority of diabetic patients (i.e., 38.95% aged >55 years with university education, 30.7% of patients aged between 46-55 years with primary education, 27.2% of middle aged patients i.e., aged between 35-45 years with secondary education, and 3.1% young adults i.e., patients aged between 25-35 years with intermediate education) were older than 46 years of age. This finding supported with another study where it was found that Obese female, age of 41–60 years are significantly have DM [

16].

Almost all the diabetic patients (98.8%) used metformin in their regimen. A majority (38.6%) of these patients used metformin for 5-10 year, followed by 37% who used it for less 5 years, and 24.4% who used metaformin for more than 10 year. Thus, metformin was noted to be a widely used drug among Hail citizens, this supported by HundaL, Ripudaman et al (2003) who concluded that; Metformin is the most widely prescribed anti-diabetic agent[

17].

The majority of these patients i.e., 68.1%, used metformin as a monotherapy drug. Only 31.9% used metformin alongside other diabetic medication, such as insulin (45.1%), linagliptin (20.7%), sitagliptin (11%), glimepiride or empagliflozin and sitagiliptin (8.5%), and a minimum number of patient (1.2%) used empagliflozin alone with metformin. The cytoprotective, oncostatic benefits of oral anti-diabetic medications are supported by meta-analysis, which also demonstrates that thiazolidinedione is connected to a lower risk of cancer, notably colorectal and breast cancers [

18].

A majority of diabetic patients (62.3 %) did not suffer from any comorbid disease along with diabetes, and only 37.7% suffered from other disease(s) along with diabetes. Out of these diseases, hypertension was found to be a predominant occurring disease (50.5% ) among diabetic patients. Long & Amanda, who showed that approximately 75% of patients with diabetes have concomitant hypertension [

19], have also supported this finding. The second disease predominantly occurring among diabetic patients was thyroid disorder (26.7%), followed by hyperlipidemia (6.2%), hyperchlosteramia (4.1%), rheumatoid arthritis (3.1%), hypertension with hypercholstremia (3.1%), hypertension & thyroid (2.1%), anemia (2.1%), hypertension with depression (2.1%), asthma (1%), and ventricular septal defect (1%).

A majority of patients (97.3%) did not suffering from breast cancer, and only 2.7% had breast cancer. Thus, it can be said that breast cancer cases declined among diabetics taking metformin. This means that metformin use is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer in women with type 2 diabetes, even in cases where these women have a family history of breast cancer. This supported byArif, J.M.etal(2010) [

20] who conclude that type 2 diabetic women on prolong treatment with metformin have low risk of breast cancer. This further indicated that a significant relation exists between the use of metformin and its effect on decreasing the risk of breast cancer in women with type 2 diabetes.

83.3% of patients did not have a family history of breast cancer while 16.7% of patients had a family history of breast cancer with first-degree (7%), followed by 4.7% of second-degree, 3.5% of third-degree and minimum number of fourth degree (1.6%) i.e. patients having high percentages of family history.

People use metformin only (64.3%) or metformin with insulin (14.4%) are less likey to have breast cancer (i.emetforin and metformin with insluin decrease the risk of breast cancer.)no literature mention both medications (i.e insulin and metformin).

The patients with co-morbid diseaseare less diagnose with breast cancer (1.2%) than those with co-morbid disease are (1.6%) (i.eco-morbid disease do not increase the risk of breast cancerthis suported by WU, Anna H., et al.(2015)who said that the risk of breast cancer–specific mortality was significantly increased among women with a history of diabetes or myocardial infarction[

21].

The patient diagnose with breast cancer that have family history of breast cancer is higher (2.33%i.e 85.35% of breast cancer patients) than those with no family history (0.39% i.e 14.29% of breast cancer patients).i.e family histery increase the risk of breast cancer among diabetics patients using metformin medication.This supported by Salinas-Martínez, et al (2014) who concluded that women with prediabetes and diabetes should be considered a more vulnerable population for early breast cancer detection[

22].

5. Conclusions

Metformin is preferable medication for Hail region patients. Insulin with metformin is the most popular medication. The majority of diseases in Hail region is diabetes and hypertension. The incidence of breast cancer disease is decrease among diabetic patients those use metformin treatment in Hail region in Saudi Arabia. The majority of patients take their medication regularly, this show clear relationship between good adherence and low incidence of breast cancer, although the Diabetes patients in Hail region have high percentage of family history of breast cancer. Co-morbid disease for diabetic patients taking metformin is not affect risk of breast cancer.We recommend in vivo animal model studies.

Supplementary Materials

Data collection tool, ethical clearance.

Author Contributions

Ahad Alenzi and Shuruq Alanazi; methodology, Taif Muqbel.; software, formal analysis, Mhdia Osman and Taif Muqbel.; investigation, resources and data curation, Taif Muqbel, Ahad Alenzi and Shuruq Alanazi; writing—original draft preparation, Mhdia Osman, Marwa H. Abdallah; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision and project administration, Mhdia Osman,Taif Muqbel, Ahad Alenzi and Shuruq Alanazi a funding acquisition, Nasrin Kalifa, Weam Khojali and Halima Mustafa Elagib are funding acquisition, Marwa helmy made extensive revewing, Weam Hussein made help in general writing and financing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethical Approval Committee of Hail University, College of Pharmacy, approved the study in number H-2021-218.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to express their Acknowledge to clinical pharmacy department in college of pharmacy; university of Hail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Franciosi, M.; Lucisano, G.; Lapice, E.; Strippoli, G.F.; Pellegrini, F.; Nicolucci, A. Metformin therapy and risk of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review. PloS one 2013, 8, e71583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanna, C.; Monami, M.; Marchionni, N.; Mannucci, E. Effect of metformin on cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2011, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Gupta, A. Management of cancer therapy–associated oral mucositis. JCO oncology practice 2020, 16, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodmer, M.; Meier, C.; Krähenbühl, S.; Jick, S.S.; Meier, C.R. Long-term metformin use is associated with decreased risk of breast cancer. Diabetes care 2010, 33, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljofan, M.; Riethmacher, D. Anticancer activity of metformin: a systematic review of the literature. Future science OA 2019, 5, FSO410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; McTiernan, A.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Manson, J.E.; Aragaki, A.K.; Rohan, T.; Ipp, E.; Kaklamani, V.G.; Vitolins, M.; Wallace, R. Diabetes, metformin, and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012, 30, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwueze, C.V.; Ogamba, O.J.; Young, E.E.; Onyenekwe, B.M.; Ezeokpo, B.C. Metformin: A possible option in cancer chemotherapy. Analytical Cellular Pathology 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabit, H.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Said, O.A.; Mostafa, M.A.; El-Zawahry, M. Metformin reshapes the methylation profile in breast and colorectal cancer cells. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP 2018, 19, 2991. [Google Scholar]

- Jiralerspong, S.; Palla, S.L.; Giordano, S.H.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Liedtke, C.; Barnett, C.M.; Hsu, L.; Hung, M.-C.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M. Metformin and pathologic complete responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in diabetic patients with breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology 2009, 27, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimova, I.N.; Liu, B.; Fan, Z.; Edgerton, S.M.; Dillon, T.; Lind, S.E.; Thor, A.D. Metformin inhibits breast cancer cell growth, colony formation and induces cell cycle arrest in vitro. Cell cycle 2009, 8, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, J.M.; Al-Saif, A.M.; Al-Karrawi, M.A.; Al-Sagair, O.A. Causative relationship between diabetes mellitus and breast cancer in various regions of Saudi Arabia: an overview. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011, 12, 589–592. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrambeigi, S.; Shafiei-Irannejad, V. Immune-mediated anti-tumor effects of metformin; targeting metabolic reprogramming of T cells as a new possible mechanism for anti-cancer effects of metformin. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 174, 113787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Elfeil, M.E.; Ahmed, S.K.; Elsammani, T.O. The in vitro Pharmacological Effects of Fagonia cretica Linn Ethanolic Extract on Isolated Rabbit Intestine. Technological Innovation in Pharmaceutical Research Vol. 9 2021, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roshan, M.H.; Shing, Y.K.; Pace, N.P. Metformin as an adjuvant in breast cancer treatment. SAGE open medicine 2019, 7, 2050312119865114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahdan-Alaswad, R.S.; Thor, A.D. Metformin Activity against Breast Cancer: Mechanistic Differences by Molecular Subtype and Metabolic Conditions. In Metformin; IntechOpen London, UK: 2020.

- Becker, J.; Nora, D.B.; Gomes, I.; Stringari, F.F.; Seitensus, R.; Panosso, J.S.; Ehlers, J.A.C. An evaluation of gender, obesity, age and diabetes mellitus as risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Neurophysiology 2002, 113, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundal, R.S.; Inzucchi, S.E. Metformin. Drugs 2003, 63, 1879–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmers, I.; Bowker, S.; Johnson, J. Thiazolidinedione use and cancer incidence in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & metabolism 2012, 38, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Long, A.N.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. The journal of clinical hypertension 2011, 13, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andújar-Plata, P.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; Laferrere, B. Metformin effects revisited. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2012, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.H.; Kurian, A.W.; Kwan, M.L.; John, E.M.; Lu, Y.; Keegan, T.H.; Gomez, S.L.; Cheng, I.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Caan, B.J.; et al. Diabetes and other comorbidities in breast cancer survival by race/ethnicity: the California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium (CBCSC). Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2015, 24, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Martínez, A.M.; Flores-Cortés, L.I.; Cardona-Chavarría, J.M.; Hernández-Gutiérrez, B.; Abundis, A.; Vázquez-Lara, J.; González-Guajardo, E.E. Prediabetes, diabetes, and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study. Archives of medical research 2014, 45, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).