INTRODUCTION

Postpartum depression (PPD) refers to a mood disorder, a mixed complex behavioral, physical, and emotional change in the woman that happens after childbirth (Lee, & Park, 2015). Postpartum depression is associated with psychological, social, and chemical changes with having a newborn (Association/APA, 2013). Perceived social support refers to the perception of being cared for by family and friends in a moment of crisis or whenever needed (Taylor, 2011). Social support can be perceived by friends, family, and significant others (Zimet et al., 1988). Empirical evidence yields that Pakistani women are at risk of PPD due to familial and cultural factors such as lack of awareness about providing special care, social and moral support to new mothers, while unlucky new mothers also tend to be reluctant to seek professional help to deal with postpartum depression because of lack of awareness (Aliani & Khuwaja, 2017; Gulamani et al., 2013). These cumbersome activities put pressure on them and consequently increase the ratio of sleep and mental health disorders among postpartum patients who visit clinics (Jiang et al., 2017; Shah & Lonergan, 2017; John, 2017).

Previous research have demonstrated that depressive symptoms and insomnia are correlated with each other in their before and after delivery (Marques et al., 2011). Furthermore, research explored that after delivery, women tend to sleep less as compared to during their pregnancy and some women also report that they spend more time awakening. However, their efficiency to fall asleep decreases from 84 percent to 75 percent after delivery(Dørheim et al., 2016; Sivertsen et al., 2017). On the contrary, the previous study also explored that postpartum symptoms are correlated with the quality of sleep among women who gave birth in the last three months (Iranpour et al., 2016). Insomnia and sleep problems are highly correlated with each other and cause symptoms of depression during and after pregnancy. On the other hand, insomnia and depression both cause negative effects on a mother’s health (Okun et al., 2015; Sivertsen et al., 2015; Dørheim et al., 2014; Stickley et al., 2019). Sleep is related to social support, physical health, and mental health (Shao et al., 2018). Consequently, a previous study revealed that postpartum depression further leads to cause depression, physical health problems, and mental health problems later in mothers (Hornby & Holleran, 2014; Abdollahi & Zarghami, 2018; Kita, 2013).

Perceived social support plays a vital role as a moderator and predictor for self-related negative life events and depression symptoms. Furthermore, their study found an interaction effect between perceived social support and negative life events in a clinical group (Miloseva et al., 2017) and depression is one of the reasons for causing postpartum depression during pregnancy (Norhayati et al., 2015). Perceived social support is found to be a moderator in the relationship between general awareness of psychological symptoms (i.e., OCD symptomology, general psychological symptoms, and Depressive symptoms) and the locus of control (Dağ & Şen, 2018; Bukhari & Afzal, 2017). However, another study determined a novel contribution of psychosocial and biological bodies to explore how neuroticism, perceived social support from the father, and cortisol reactivity contribute to increasing the level of depression during pregnancy (Kofman et al., 2019). Moreover, multiple studies determined that prenatal depression is at risk and complicated by psychosocial (i.e., social support, stress, relationship quality) and biological factors (e.g., inflammatory, endocrine, genetic) (Yim et al., 2015). The study conducted by Kwok, Yeung & Chung reported that perceived peer support and physical functional disability are true predictors of depressive symptoms in elders. However, perceived social support is a non-significant predictor when stratified for education level and gender (Kwok et al., 2011).

The current study aimed to investigate how postpartum depression affects the mental and physical health of Pakistani women by exploring the role of social support in the period of postpartum depression. This research has highlighted some gaps in the literature that need to be addressed in future research to develop optimal evidence-based policy decisions and service provision. The uniqueness of the study is to explore the mental health of females who suffered from postpartum depression and to examine their physical health as well.

H1. There would be a relationship between Postpartum Depression, insomnia, mental health, physical health and perceived social support among women.

H2. Postpartum Depression would be a significant predictor of insomnia, mental health, physical health and perceived social support

H3. Social support would be a significant predictor of postpartum depression, mental health and physical health.

H4.There would be the moderating role of social support in the relation between postpartum depression and mental health.

H5. Employed women who are uneducated would have more postpartum depression as compared to educated unemployed women.

METHODS

Materials and Procedures

A cross-sectional research approach was used for the present study. Purposive sampling technique was used and the sample was recruited between March 2019 to May 2019 from the gynecology and obstetrics outpatient departments where the mothers came to visit gynecologists after childbirth during their postpartum phase. The women who cannot read were assisted by the researcher by reading out all questions and then marking their all responses. Data was collected from 385 participants but after screening it for missing values, outliers, and random responses, 320 were selected for data analysis.

The eligibility criteria were the woman who had been in the postpartum phase in the first two to four weeks following childbirth. The terms puerperal period, puerperium, or the immediate postpartum phases are commonly referred to as the first six weeks following childbirth (Romano, et al., 2010). All women ages were ranged 16 and above with one or any number of babies were included. In Pakistan, the legal age of adulthood is about 18- years old for a male to get married and 16 years old for a female to get married (Child & Legislation, 2018). However, women younger than 16 years or with mental health disorders other than PPD were also excluded.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Sargodha, Pakistan. Before data collection, permission was obtained from the Department of Psychology, University of Sargodha and from the hospital’s Medical Superintendent (MS) to conduct this research. Procedures and the purpose of the study were introduced and informed consent was obtained from participants. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured for data responses. This study strictly followed the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Measures

The variables of postpartum depression, insomnia, mental health, somatic problems and perceived social support were measured by the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS), Pittsburg sleep quality index (PSQI), Warwick-Edinburgh mental wellbeing scale (WEMWBS), Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) respectively.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): To measure postpartum depression in women, EPDS was used for this study, developed by Cox et al. (Cox et al., 1987). This scale consists of 10 items in which every item has specific function to analyze such as anhedonia, self-blame, anxiety, Fear, coping inability, sleeping, sadness, tearfulness and self-harm (Teissèdre & Chabrol, 2004). Every item of this scale has a different response format which is scored from 0 to 3 and adding the item's score of each question make a total range of 0 to 30. The anchor of the scale is different in each question. The alpha reliability of this scale is 0.92. A high value on this scale shows the signs of postpartum depression and a low value shows no sign of depression in any way.

Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): Quality of sleep was measured by the PSQI, which was developed by some researchers of the University of Pittsburg (Buysse et al., n.d.). This scale consists of 15 items of multiple-choice questions. These items measure the seven different components of sleep which includes sleep latency, subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep duration, use of sleep medication, sleep disturbance, and daytime dysfunction. Scoring ranges from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty) and by adding the items scores of each question ranges from 0 to 21. The reliability of this scale is 0.56. On this scale, a high score shows sleep interruption, while a low score s good shows sleep.

Warwick- Edinburg Mental Wellbeing scale: To measure the mental health of women, Warwick Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) was used in the present study. This scale was developed by Stewart and his colleagues in 2009 and it was designed to have information about mental well-being, including cognitive evaluation dimensions, affective emotional aspects, and psychological functioning (Stewart et al., 2009). This scale consists of 14 items. The format of response was five points Likert scale and the score ranges from 1 to 5. The reliability for this scale is 0.79. The high value on the scales shows positive high mental health.

Patient health questionnaire: The physical health of the woman was measured by the Patient health questionnaire which was developed by Kroenke and his colleagues in 2001 (Kroenke et al., n.d.). This scale is based on 9-item questionnaire and the score ranges from 0 to 3 while the total score ranged from 0 to 27. The reliability for this scale is 0.59. A high value on this measure shows severe physical ailment, while a lower rating shows mild physical ailment.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): Perceived social support was measured by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support which was developed by Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley in 2010 (Zimet et al., 2010). MPSS consists of 12 items on seven points Likert scale which ranged from 1 to 7. This scale has three subscales with 4 items for each subscale which indicates the support of friends, family, and significant others. However, 4 items (1, 2, 5, 10) assess the support of significant others, 4 items (3, 4, 8, 11) assess the support of family and 4 items (6, 7, 9, 12) assess the support of friends. The reliability of the total scale is 0.71. A high value on this scale shows high social support and a low value indicates a lack of social support.

Statistical Analysis

Following data collection, descriptive statistics were used to show the frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation of study variables. Cronbach’s Alpha analysis was done to find the internal consistency for study instruments. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationship between variables (name the variables), linear regression analysis was done to analyze postpartum depression and perceived social support are predictors of somatic health, mental health and Insomnia. hierarchal regression analysis was performed to show that perceived social support has moderating role between postpartum depression and mental health, and two-way ANOVA analysis was performed to show the main effect of education (write the different levels of education) on postpartum depression. All hypotheses of the study were tested by using IBM SPSS (version 24) and Alpha was fixed at the 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the percentage and frequency of study variables i.e., Age, Education, Delivery type, Newborn gender, Employment, Family system, number of children, daughters and sons and Socioeconomic status. The table shows that the education level of women was low (39.4%) and they live in a nuclear family system (78.8%). It also shows that most women had C- Section delivery (64.7%). Furthermore, the result shows that most women have 0 to 4 children (83.4%).

The results of

Table 2 show mean, standard deviation, alpha reliabilities and correlation among variables of the study. Alpha reliabilities coefficient of overall scales along subscales ranges from 0.29 to 0.92 respectively. Correlation analysis shows that postpartum depression has significant positive relationship with physical health (

r= .45,

p<.000), significant negative relationship with insomnia (

r= -.24,

p<.000) and perceived social support (

r= -.38,

p<.000) along with sub-constructs (name the constructs). Furthermore, correlation analysis explores the relationship of insomnia with other variables and found a significant negative relationship with physical health (

r= -.14,

p<.05), positive relationship with perceived social support (

r= .17,

p<.05), and with significant others (

r= .16,

p<.05).

The result indicates the predictive capability of postpartum depression for insomnia, physical health, mental health, and perceived social support. The R2 value of 0.06 indicates a 6% variation in the dependent variable which might account for post-partum depression [F (2, 318) =13.82]. These findings indicate that postpartum depression has been a significant predictor of insomnia (R2=.06, p= .000, and β = -.24). Results also revealed significant results for physical health, R2value of 0.45 indicates a 45% variation in the dependent variable which might account for, postpartum depression [F (2, 318) =56.73]. The above findings show that postpartum depression is an important predictor of physical health (R2=.45, p= .000, and β = .21). However, postpartum depression is a non-significant predictor of mental health. Moreover, postpartum depression has been a significant predictor of social support. The R2 value of 0.14 indicates that 14% variation in the dependent variable which might be accounted for, through postpartum depression [F (2, 318) =.36.81]. These findings indicate that postpartum depression has been a significant predictor of perceived social support (R2=.14, p= .000, and β = -.38).

The result shows the predictive capability of perceived social support with their sub-constructs for postpartum depression, insomnia, physical health, and mental health. Results indicate that perceived social support has been a significant predictor of postpartum depression (R2 = .14, p= .000, and β = -.38). The value of R2 of 0.14 shows a 14% variation in postpartum depression, which might be accounted for, through perceived social support [F (2, 318) =36.81]. Results also indicate that social support has been significant predictor for insomnia (R2 = .02, p= .012 and, β = .16). R2value of 0 .02 indicates that only a 2% variation in the dependent variable might be accounted for, through perceived social support [F (2, 318) =6.41]. However, perceived social support has been a non-significant predictor of mental health. Furthermore, results show that social support has been a significant predictor of physical health (R2 = .05, p= .000, and β = -.23). The value R2 of 0.05 shows that a 5% variation in physical health might be accounted for, through perceived social support [F (2, 318) =12.67]. However, results show that sub-constructs were also significant predictors for study variables.

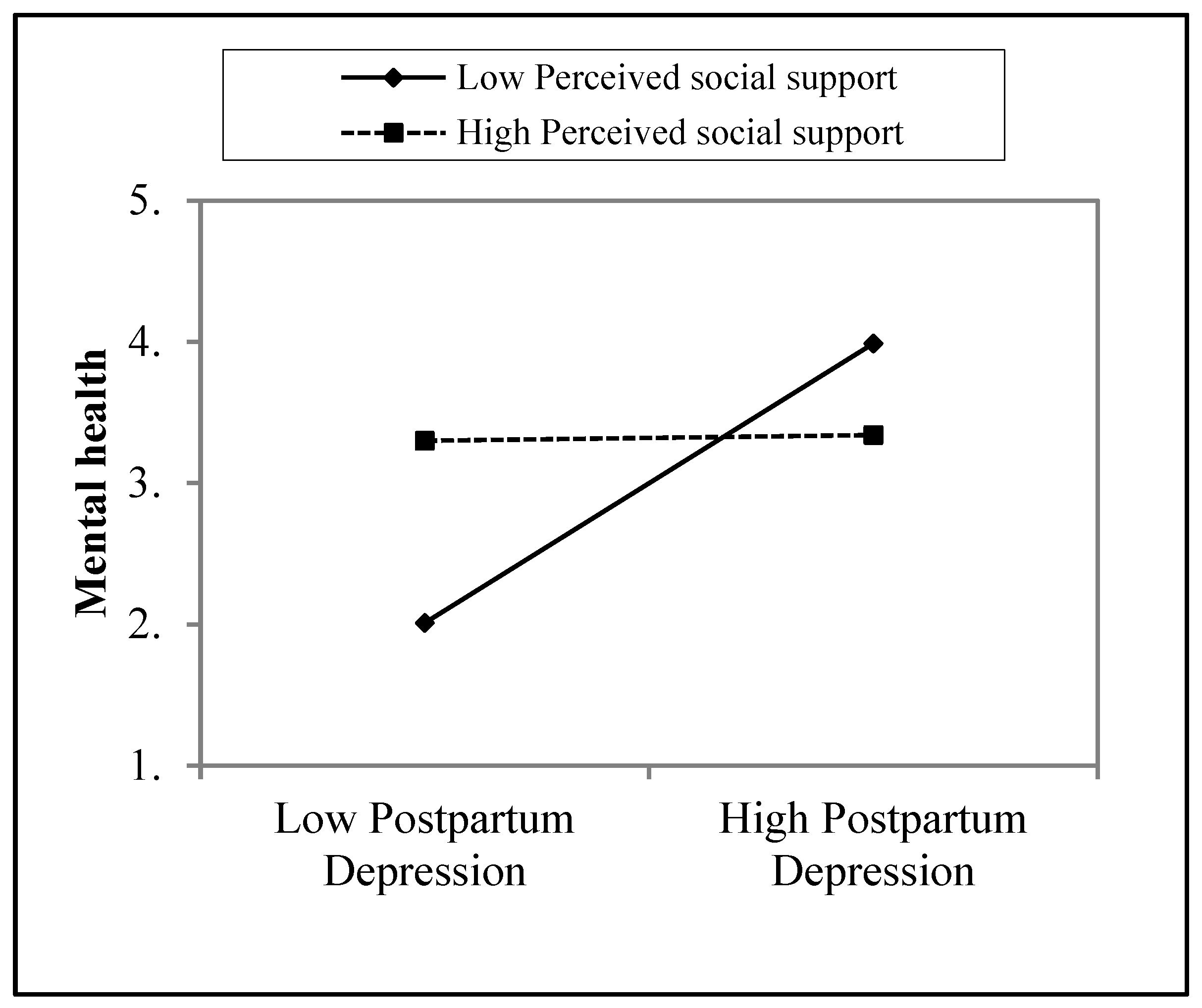

Table 5 demonstrates moderating effect of Perceived social support (PSS) in relationship between postpartum depression (PPD) and mental health. Overall model 1found to be non-significant {

∆ R2 = .00

, f (1,318) = .26,

p >.05} as postpartum depression is contributing 0% variance in dependent variable (

R2=.00, .607,

β =-.03). Overall model 2 also found to be non-significant {

∆ R2 =.00,

f (1,317) = .13,

p > .05} and postpartum depression is contributing 0% variance in dependent variable (

R2=.00, .641,

β = 00). However, overall model 3 reveals to be significant {

∆ R2=.03,

f (1,316) = 2.67,

p >.05} interaction of postpartum depression and perceived social support are contributing 3% variance in dependent variable (

R2=.03, p=.006,

β = .97).

The crossed lines on the graph suggest that there is an interaction effect, which is significant for the perceived social support. The graph shows that level of perceived social support is higher for those women whose mental health increased by postpartum depression (

Figure 1).

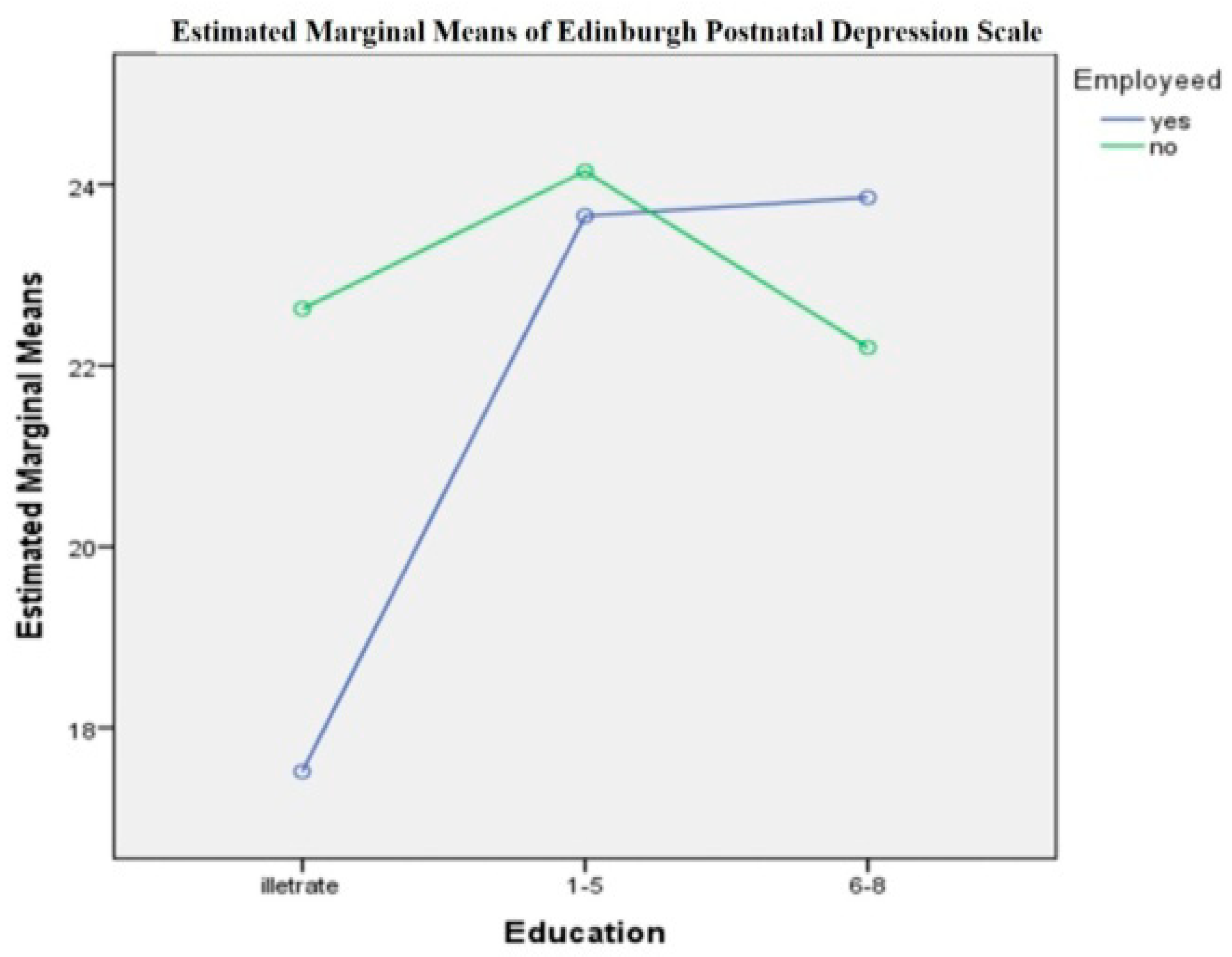

Table 6 shows the main effect of educational on postpartum depression founded significant {

F (2, 317) = 15.34,

p < .001}, and meanwhile, the main effect of employment on postpartum depression was also founded significant {

F (2, 317) = 4.64,

p < .05}. Nevertheless, interaction of Education and Employment was founded significant {

F (2, 317) = 10.04,

p < .001}. Results also shows that women who were educated {primary (

M = 23.90) and middle (

M = 23.02)} and unemployed (

M = 22.99) have more postpartum depression as compared to uneducated women {illiterate (

M = 20.07)} who were employed (

M = 21.67).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated relationships among study variables and significant results were founded which shows that this hypothesis was accepted (Rephrase this) (see

Table 2). Results show that postpartum depression is negatively related to insomnia, mental health, physical health, and perceived social support which indicates that when women suffered more level of postpartum depression they perceived less social support which affected their sleep, and mental and physical health. The reason for this can be that when women faced more postpartum depression they were more in need of a consultant (i.e., a psychologist) rather than have social support so it can help them to maintain health. Another reason can be that usually at a postpartum phase in labor women have more family members from in-laws than their blood relatives to whom they perceived more supportiveness in comparison with their in-laws. Data were collected from women belonging to rural areas, with a low level of education, which makes them shy so they couldn’t share their symptoms of postpartum depression. However, those women whose newborn child is female feel more depressed as the Pakistani culture shows gender discrimination against baby girls. So this could also be the reason that females don’t perceive social support in the postpartum phase which ultimately affects the health of the woman.

This hypothesis was supported by some previous studies. The previous study has investigated that insomnia is stable in women during their pregnancy until two years in the postpartum period with three latent classes which describe the best trajectories; 1: stable low, 2: stable medium, and, 3: stable high (Sivertsen et al., 2015). Studies found the relationship between the postpartum symptoms and quality of sleep among women who gave birth in the last three months (Iranpour et al., 2016). Research (Bukhari & Afzal, 2017) has determined that postpartum depression is negatively related to perceived social support among women in Pakistan. A recent study founded a negative relationship between social support and postpartum depression. The study showed that they perceived social support so that they can take care of their babies since women are at high (34.5%) risk for having postpartum depression (Tambag et al., 2018). Another study also determined that social support, mental health, health-related quality of life have a relationship with each other’s (Shao et al., 2018). Another study investigated that postpartum depression predisposes women to develop physical health issues, mental health problems and chronic depression later in life so it needs to be identified early in order to avoid health problems and provide social support (Abdollahi & Zarghami, 2018).

The second hypothesis of the current study was that Postpartum Depression would be a significant predictor of Insomnia, mental health, physical health and perceived social support. Results indicate that postpartum depression is a significant predictor of insomnia, physical health, and perceived social support but not a true predictor of mental health (see

Table 3). The latest studies make a novel contribution to accepting this hypothesis. Research by Kofman and his colleagues combined psychosocial and biological bodies to explore how neuroticism, perceived social support from the father, and cortisol reactivity contribute to increasing the level of depression during pregnancy (Kofman et al., 2019). What did they found out?? Another study investigated that mental health problems and sleep disorders increase the chances of people visiting clinics (Jiang et al., 2017). Moreover, a study demonstrated that women after delivery, sleeps less as compared to before delivery. However, their sleep capacity reached 75 percent from 85 percent with awakenings at night times (Dørheim et al., 2016).

Another hypothesis was that if social support will be a predictor of postpartum depression, mental health, and physical health. Findings indicate that social support is a predictor of postpartum depression, insomnia, and physical health but not a true predictor of mental health (see

Table 4). A previous study has supported this hypothesis. A study by Gan and his colleagues discovered that perceived social support has a signifiant effect on postpartum dépression (Gan et al., 2019)(Vaezi et al., 2019) and physical activities (Kang et al., 2016). However, another study demonstrated that perceived social support has a strong association with the quality of life and mental health of cancer patients (Eom et al., 2013). Perceived social support has a significant impact on the quality of life related and symptoms of depression in general people and survivors of cancer illness (Yoo et al., 2017).

The fourth hypothesis of the study was if there would be a moderating role of Perceived social support in the relationship between postpartum depression and mental health. The result indicates that perceived social support has a significant moderating role in the relationship between postpartum depression and mental health (see

Table 5 and

Figure 1). This hypothesis is supported by previous research in which perceived social support was found to be a significant predictor and the moderator which works as a stress-buffering variable between depressive symptoms and stressful negative life events. A further study explored that perceived social support is a moderator in the relationship between perceived social support and the negative life events among clinical groups (Miloseva et al., 2017). Another study also found perceived social support as a moderator in the relationship between common causality awareness (i.e., psychological symptoms and general symptoms) and locus of control (Dağ & Şen, 2018). A previous study explored that perceived social support is a significant moderator that affects perfectionism in depression (Zhou et al., 2013). Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that perceived social support plays the role of a moderator in the relationship between subjective wellbeing and perceived discrimination among physically disabled people of Israel (Itzick et al., 2018).

The fifth hypothesis of the study was employed Uneducated women would have more postpartum depression as compared to educated unemployed women. The result shows that women who were educated and unemployed have more postpartum depression as compared to uneducated women who were employed (see

Table 6 and

Figure 2). Findings are supported by the study of Azad et al conducted in 2019who found that postpartum depression prevalence was higher among uneducated women as compared to those women who were educated. Furthermore the prevalence of depression was common in an employed woman as compared to an unemployed woman (Azad et al., 2019). Findings are similar to old studies which explore prevalence ratios in different developed countries, and they found that these different sources are biological and they seldom depend on culture, race, diet, education and other economic and social factors. However, there is no actual evidence for these differences (Albert, 2015).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis for Postpartum depression predicting Insomnia, Physical health, perceived social support and Mental health (N= 320).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis for Postpartum depression predicting Insomnia, Physical health, perceived social support and Mental health (N= 320).

| Variable |

INS |

PH |

MH |

PSS |

| |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

| PPD |

-.24*** |

.06 |

13.82 |

.21*** |

.45 |

56.73 |

-.03 |

.00 |

.26 |

-.38*** |

.14 |

36.81 |

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of social support along sub-constructs predicting Postpartum depression, Insomnia, Mental health and Physical health (N= 320).

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of social support along sub-constructs predicting Postpartum depression, Insomnia, Mental health and Physical health (N= 320).

| Predictor variables |

PPD |

INS |

MH |

PH |

| |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

β |

R2 |

F |

| PST |

-.38*** |

.14 |

36.81 |

.16* |

.02 |

6.41 |

.01 |

.00 |

.04 |

-.23*** |

.05 |

12.67 |

| FM |

-.21** |

.04 |

10.59 |

.12 |

.01 |

3.30 |

.18** |

.03 |

8.04 |

-.20** |

.04 |

9.04 |

| FR |

-.33*** |

.11 |

28.37 |

.09 |

.01 |

2.15 |

-.08 |

.00 |

.07 |

-.22** |

.04 |

11.34 |

| SO |

-.31*** |

.09 |

23.03 |

.15* |

.02 |

5.65 |

-.06 |

.00 |

.84 |

-.14* |

.01 |

4.78 |

Table 5.

The moderating role of perceived social support in the relationship between postpartum depression and mental health (N= 320).

Table 5.

The moderating role of perceived social support in the relationship between postpartum depression and mental health (N= 320).

| Models |

R2 |

β |

F |

| Model 1 |

.00 |

|

.26 |

| (PPD) |

|

-.03 |

|

| Model 2 |

.00 |

|

.13 |

| (PPD) |

|

-.03 |

|

| (PSS) |

|

.00 |

|

| Model 3 |

.03 |

|

2.67 |

| (PPD) |

|

.99** |

|

| (PSS) |

|

.32* |

|

| (PPD)x(PSS) |

|

-.97** |

|

| Total R2 |

.03 |

|

|

Table 6.

Two-Way-ANOVA for the Interaction and main Effect of the Education and Employment on postpartum depression (N = 320).

Table 6.

Two-Way-ANOVA for the Interaction and main Effect of the Education and Employment on postpartum depression (N = 320).

| Sources |

SS |

MS |

F |

Partialη²

|

| Education |

598.59 |

299.30 |

15.34*** |

.125 |

| Employment |

90.78 |

90.78 |

4.64* |

.021 |

| Education*Employment |

396.18 |

196.09 |

10.04*** |

.086 |

There were some limitation to this study. . The EPDS scale was developed to measure postpartum depression but it has similarities with other scales of depression. Future researchers should also interview to get more detailed information. Data was collected from the females who were uneducated or had a lower level of education so it was difficult to get data from uneducated women because they cannot read the questionnaire so researcher has asked those questions and write their answers as responses. As in this study, the total sample was 320 so I will suggest future researcher interviews with a large sample size to study postpartum depression in an uneducated woman.

The findings of this study may not be generalizable to all Pakistani women because it did not include females at the edges of the reproductive period continuum to let a comparison. After all, some women were having premature infants, some women were poor, and some were having a history of stillbirth, but were having other mental health-related diagnoses. Future researchers should have to work more on the reproductive period and try to get a sample with fewer physical and mental issues. Further studies should also work on the treatment of sleep, and mental and physical problems in a woman which will lead to a decrease in the level of depression in the postpartum Phase.

CONCLUSIONS

This study concluded that postpartum depression has a positive relationship with physical health, and a negative relationship with insomnia, and perceived social support. Finding also concluded that postpartum depression and social support are significant predictors of insomnia, physical health and perceived social support. Similarly, results further concluded that perceived social support played a significant moderating role in the relationship between postpartum depression and mental health among females. Moreover, findings concluded that there was a high level of postpartum depression in working women who were uneducated as compared to unemployed educated women.

References

- Abdollahi, F., & Zarghami, M. (2018). Effect of postpartum depression on women’s mental and physical health four years after childbirth. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 24(10), 1002–1009. [CrossRef]

- Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 40(4), 219–221. [CrossRef]

- Ali Burhan Mustafa, Rusham Zahra, M. H. R. (2016). Postpartum Depression in Pakistan-Suffering in Silence. [CrossRef]

- Aliani, R., & Khuwaja, B. (2017). Epidemiology of Postpartum Depression in Pakistan: A Review of Literature. National Journal of Health Sciences, 2(1), 24–30. [CrossRef]

- Association/APA, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Azad, R., Fahmi, R., Shrestha, S., Joshi, H., Hasan, M., Khan, A. N. S., Chowdhury, M. A. K., Arifeen, S. El, & Billah, S. M. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression within one year after birth in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 14(5), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S. R., & Afzal, F. (2017). Perceived Social Support predicts Psychological Problems among University Students. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(2), 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D. J., Angst, J., Gamma, A., Ajdacic, V., Eich, D., & Rössler, W. (n.d.). Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W (2008). Prevalence, Course, and Comorbidity of Insomnia and Depression in Young Adults. Sleep.31(4):473-480. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of Postnatal Depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(JUNE), 782–786. [CrossRef]

- Dağ, İ., & Şen, G. (2018). The mediating role of perceived social support in the relationships between general causality orientations and locus of control with psychopathological symptoms. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 14(3), 531–553. [CrossRef]

- Dørheim, S. K., Bjorvatn, B., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2014). Can insomnia in pregnancy predict postpartum depression? A longitudinal, population-based study. PLoS ONE, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Dørheim, S. K., Garthus-Niegel, S., Bjorvatn, B., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2016). Personality and Perinatal Maternal Insomnia: A Study Across Childbirth. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 14(1), 34–48. [CrossRef]

- Eom, C. S., Shin, D. W., Kim, S. Y., Yang, H. K., Jo, H. S., Kweon, S. S., Kang, Y. S., Kim, J. H., Cho, B. L., & Park, J. H. (2013). Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients: Results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psycho-Oncology, 22(6), 1283–1290. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y., Xiong, R., Song, J., Xiong, X., Yu, F., Gao, W., Hu, H., Zhang, J., Tian, Y., Gu, X., Zhang, J., & Chen, D. (2019). The effect of perceived social support during early pregnancy on depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum: A prospective study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gulamani, S. S., Shaikh, K., & Chagani, J. (2013). Postpartum depression in Pakistan: A neglected issue. Nursing for Women’s Health, 17(2), 147–152. [CrossRef]

- Hornby, T. G., & Holleran, C. L. (2014). Sleep matters. In Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy (Vol. 38, Issue 3). [CrossRef]

- Iranpour, S., Kheirabadi, G. R., Esmaillzadeh, A., Heidari-Beni, M., & Maracy, M. R. (2016). Association between sleep quality and postpartum depression. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 21(8), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Itzick, M., Kagan, M., & Tal-Katz, P. (2018). Perceived social support as a moderator between perceived discrimination and subjective well-being among people with physical disabilities in israel. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(18), 2208–2216. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Tang, Y. R., Xie, C., Yu, T., Xiong, W. J., & Lin, L. (2017). Influence of sleep disorders on somatic symptoms, mental health, and quality of life in patients with chronic constipation. Medicine (United States), 96(7), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- John, V. G. (2017). Predictors of Postpartum Depression among Women in Karachi, Pakistan. Predictors of Postpartum Depression among Women in Karachi, Pakistan, 1. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=129592988&lang=es&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Kabakian-Khasholian, T., Shayboub, R., & Ataya, A. (2014). Health after childbirth: Patterns of reported postpartum morbidity from Lebanon. Women and Birth, 27(1), 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. W., Park, M., & Wallace (Hernandez), J. P. (2016). The impact of perceived social support, loneliness, and physical activity on quality of life in South Korean older adults. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 7(2), 237–244. [CrossRef]

- Kita, L. E. (2013). Investigating the Relationship between Sleep and Postpartum Depression. October.

- Kofman, Y. B., Eng, Z. E., Busse, D., Godkin, S., Campos, B., Sandman, C. A., Wing, D., & Yim, I. S. (2019). Cortisol reactivity and depressive symptoms in pregnancy: The moderating role of perceived social support and neuroticism. Biological Psychology, 147. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (n.d.). The PHQ-9. 46202, 606–613.

- Kwok, S. Y. C. L., Yeung, D. Y. L., & Chung, A. (2011). The moderating role of perceived social support on the relationship between physical functional impairment and depressive symptoms among Chinese nursing home elderly in Hong Kong. TheScientificWorldJournal, 11, 1017–1026. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. J., & Park, J. S. (2015). Development of a prediction model for postpartum depression: Based on the mediation effect of antepartum depression. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 45(2), 211-220. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M., Bos, S., Soares, M. J., Maia, B., Pereira, A. T., Valente, J., Gomes, A. A., Macedo, A., & Azevedo, M. H. (2011). Is insomnia in late pregnancy a risk factor for postpartum depression/depressive symptomatology? Psychiatry Research, 186(2–3), 272–280. [CrossRef]

- Miloseva, L., Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T., Richter, K., Milosev, V., & Niklewski, G. (2017). Perceived social support as a moderator between negative life events and depression in adolescence: implications for prediction and targeted prevention. EPMA Journal, 8(3), 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Norhayati, M. N., Nik Hazlina, N. H., Asrenee, A. R., & Wan Emilin, W. M. A. (2015). Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 34–52. [CrossRef]

- Okun, M. L., Buysse, D. J., & Hall, M. H. (2015). Identifying insomnia in early pregnancy: Validation of the Insomnia Symptoms Questionnaire (ISQ) in pregnant women. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 645–654. [CrossRef]

- Romano, M., Cacciatore, A., Giordano, R., & La Rosa, B. (2010). Postpartum period: three distinct but continuous phases. Journal of prenatal medicine, 4(2), 22.

- Shah, S., & Lonergan, B. (2017). Frequency of postpartum depression and its association with breastfeeding: A cross-sectional survey at immunization clinics in Islamabad, Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 67(8), 1151–1156.

- Shao, B., Song, B., Feng, S., Lin, Y., Du, J., Shao, H., Chi, Z., Yang, Y., & Wang, F. (2018). The relationship of social support, mental health, and health-related quality of life in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men who have sex with men: From the analysis of canonical correlation and structural equation model: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (United States), 97(30), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, B., Hysing, M., Dørheim, S. K., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2015). Trajectories of maternal sleep problems before and after childbirth: A longitudinal population-based study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, B., Petrie, K. J., Skogen, J. C., Hysing, M., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2017). Insomnia before and after childbirth: The risk of developing postpartum pain—A longitudinal population-based study. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 210, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D., Bowers, L., Simpson, A., Ryan, C., & Tziggili, M. (2009). Manual restraint of adult psychiatric inpatients: A literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(8), 749–757. [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A., Leinsalu, M., DeVylder, J. E., Inoue, Y., & Koyanagi, A. (2019). Sleep problems and depression among 237 023 community-dwelling adults in 46 low- and middle-income countries. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review.

- Tambag, H., Turan, Z., Tolun, S., & Can, R. (2018). Perceived social support and depression levels of women in the postpartum period in Hatay, Turkey. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 21(11), 1525–1530. [CrossRef]

- Teissèdre, F., & Chabrol, H. (2004). Detecting Women at Risk for Postnatal Depression Using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at 2 to 3 Days Postpartum. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(1), 51–54. [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, A., Soojoodi, F., Banihashemi, A. T., & Nojomi, M. (2019). The association between social support and postpartum depression in women: A cross sectional study. Women and Birth, 32(2), e238–e242. [CrossRef]

- Yim, I. S., Stapleton, L. R. T., Guardino, C. M., Hahn-, J., Schetter, C. D., Behavior, S., & Angeles, L. (2015). Depression : Systematic Review and Call for Integration. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 99–137. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H., Shin, D. W., Jeong, A., Kim, S. Y., Yang, H. K., Kim, J. S., Lee, J. E., Oh, J. H., Park, E. C., Park, K., & Park, J. H. (2017). Perceived social support and its impact on depression and health-related quality of life: A comparison between cancer patients and general population. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 47(8), 728–734. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Zhu, H., Zhang, B., & Cai, T. (2013). Perceived social support as moderator of perfectionism, depression, and anxiety in college students. Social Behavior and Personality, 41(7), 1141–1152. [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., Gordon, K., & Farley, G. K. (2010). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of personality assessment, 52(1), 30-41. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).