1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) covering social development, economic development, environmental protection and cooperation, to ensure the sustainable development of countries. Sustainable development is based on three fundamental dimensions—economic growth, societal well-being and environmental quality—ensuring the sustainable development of all three, without prioritising any one over the other two. The authors note that nowadays, it is especially pertinent and essential to developing the scientific debate by representing the interaction of these three dimensions from an interdisciplinary perspective when a country’s modernisation trends are directly correlated with the field of social environment sustainability. It should be stressed that the field of modernisation of a country reduces to the construction of new parallels of thinking, assessing the sustainability of the social environment and the criteria of modernisation, emphasising the change in the concept of the 'modernisation revolution', i.e., highlighting the qualitative aspect of the modernisation of society [

1].

The European Social Survey (ESS) is a new approach to modernisation. The ESS is a biennial international survey initiated by researchers concerning the attitudes, beliefs and behaviour of people in different countries. Its main objectives are: to monitor changes in Europe’s social, political and value picture; to develop and implement a high-standard methodology for international social surveys; for training purposes; to increase access to data; and to use reliable indicators of national progress [

2]. The Social Progress Imperative, a US non-profit organisation, calculates a social progress index based on three components: basic human needs, well-being and opportunity. Lithuania’s progress strategy, Lithuania 2030, identifies specific indicators to monitor change and set targets: the Quality of Life Index; the Happiness Index; the Democracy Index; and the Sustainable Society Index. The study shows that many instruments are used to assess the social environment. Moreover, there is a dearth of comprehensive research on the topic of social environment sustainability, which could suggest theoretical conceptions of the country’s modernisation, well as the empirical data. Based on this methodological stance, the research questions are: how does this conceptual shift reflect the changes in the country’s modernisation in the context of the sustainability of the social environment; and what are the implications for society?

The aim of this paper is to develop an integrated system of indicators for the formation of a modern country and the directionality of its governance following an analysis of the country’s modernisation trends in terms of the social environment. To achieve this goal, three hypotheses are formulated:

H1. The better developed the education system and educational culture of a nation, the more modern the country is in the context of social environment.

H2. The better the social support and socio-economic integration is in a nation, the more modern the country is in the context of the social environment.

H3. The better developed the legal system is and the more significant the public governance and citizenship are, the more modern the country is in the context of the social environment.

The next section provides a summary of the relevant literature on modernisation, the modernisation processes, and sustainable social environments. The third section provides a methodological framework for the methods used: descriptive statistics, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM). The fourth section discusses the results, highlighting the practical/managerial implications of the insights gained, and the final section presents the contribution and limitations of the study and offers perspectives for future research.

2. Modernisation of the Country

A country’s development is inextricably linked to its social, economic and political environment. The analysis of different sources reveals a contradiction in the definition of modernisation, however. In [

3] Marcinkevičienė summarised the results of the study of Soviet historiography throughout the works of different foreign authors. Contradictions have been noted in the definitions of modernisation and the beginning of modernisation; however, it is emphasised that the modernisation processes vary between countries. There are also contradictions regarding the modernisation of Lithuania and its preconditions [

4]. Similarly, there is disagreement as to which year (1861 or later) is considered the beginning of the modernisation era. However, a concept is put forward: the modern Lithuanian nation is not a nationality, nor are 'ethnic Lithuanians' the main subject of Lithuanian history in the modern period. The basis of modernisation is the transformation of the economy and economic relations, agriculture and industry, which are associated with changes in the social and political order. In his article [

5], the historian Nefas reviews the facts of the beginning of modern Lithuania (1918) from a historical perspective. Although there is no unanimous agreement on the beginning, there is a general view that a modern state is inseparable from continuous progress and exceptional achievements.

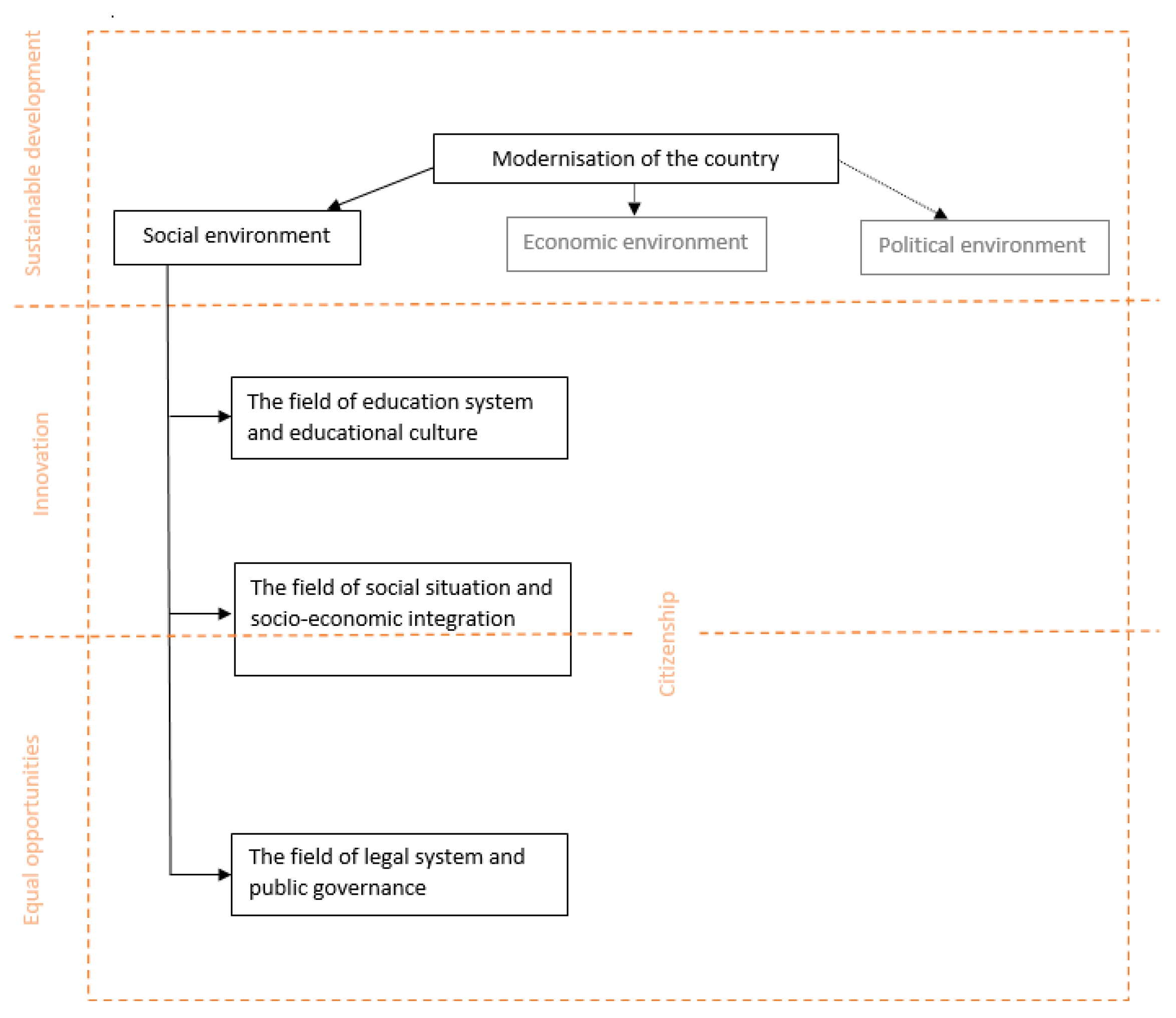

In the academic literature concerning the modernisation processes, there is a general consensus that the driving force behind modernisation has, in any case, been economic or economic development [

4]. The modernisation theory distinguishes between 'traditional' and 'modern' forms of society, politics and economics, and examines the circumstances and policies that should contribute to higher levels of development [

6]. The authors have drawn up a flowchart for the study of modernisation in the country, taking into account the analysis of the scientific literature and the National Progress Plan [

7] (see

Figure 1).

According to

Figure 1, three environments are identified: social, economic and political. The social environment includes three fields of research: the education system and educational culture, the social situation and socio-economic integration, the legal system and public governance, and the importance of citizenship. The flowchart also displays three horizontal dimensions: sustainable development, innovation and equal opportunities.

2.1. A Sustainable Social Environment

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the Sustainable Development Goals. These identified additional areas for the environment and cooperation. Sustainable development is understood in the scientific literature as a complex concept and a complex process [

8], which aims to ensure the well-being not only of current generations but also of future generations. In [

9], other scholars emphasise the non-depletion of key resources, while [

10] other scholars define sustainable development as development that maintains the stability of the system and develops a balance between economic, social and environmental development without endangering future generations. Klarin’s analysis of the scientific sources of the concepts of sustainable development and growth summarised sustainable development in 3 dimensions are: 1) the concept of development (socio-economic development that meets ecological constraints), 2) the concept of needs (redistribution) of resources to ensure the quality of life for all), and 3), the concept of future generations (the possibility of sustainable use of resources to ensure the necessary quality of life for future generations) [

11].

The socio-environment is one of the components of sustainable development. A literature review has shown that there is no single definition of the term 'sustainable social environment'. As defined by Colantonio, this is because as a concept, it is too complex to be unambiguously defined [

12]. The most common way of presenting it is through the influencing factors, i.e., some scholars [

13] analyse the social environment in terms of the following factors: access to basic needs; housing; health; safety; security; education; equity; demographics; poverty level; culture; recreation; and access to credit [

13]. Činčikaitė (2013) described the social environment through the following factors: human capital; migration; social burden on the city; urban safety, community learning, partnership and activism; social cultural and sports infrastructure, education and education system; psychological climate of the city; the demographic situation of the city; and medical care infrastructure [

14].

Several scholars have emphasised community involvement in their work on sustainable social environments [

12,

15,

16]. Others have identified the factors that define the social environment: public transport, health and social protection (health and social protection infrastructure), education and science (general, vocational and post-secondary education systems, research infrastructure), and public safety infrastructure [

17,

18]. Schools, social and health care institutions, hospitals, and anything else that guarantees that social needs are met contributes to the growth of the national economic level, as the network of social infrastructure enables a country’s residents to acquire the education, vocational skills, and qualifications that they apply to their jobs [

18].

Education in the context of sustainable development is part of social capital [

8]. This is not only about the education system of the state, but also about the integration of the essential elements of sustainable development into learning (UNESCO) to change the behaviour of the population. Global education is an active learning process based on solidarity, equality, inclusion and cooperation. It aims to provide knowledge about sustainable development, to understand the challenges facing the world and their causes, to understand the impact of local actions on global processes, and to empower people to engage with the international sustainable development goals [

8]. Melnikas identified the emergence of a new type of society, perceived as a knowledge society, which reflects the transformation of society itself into a qualitatively new state [

19].

The economic prosperity of any country depends on its population. It is particularly important to study the structure of the working-age population because, according to [

20], the population aged 30–44 has the greatest impact on labour productivity growth, the population aged 50–64 has a positive impact, and the population aged over 65 has a negative impact. With the continuing rise in the importance of the labour factor in the market, the quality of the labour force is becoming more and more important, with the negative impact of the 'brain drain', defined as the departure of educated or professional people for reasons such as better working and living conditions [

21]. The decision to emigrate is usually based on economic motives and personal or professional self-fulfilment; however, some emigrants have also identified social and legal insecurity as an important factor influencing their migratory behaviour. The latter processes are increasingly influenced by international migration, which has become an integral part of life in modern societies in the late 20th and early 21st centuries [

22]. Researchers Yushi Zhang et al. studied urban-rural migration and found that social protection has a significant positive impact on rural-urban migration, while improving the sense of fairness, happiness and security promotes the rural population’s desire to integrate and identity and encourages urbanisation. Social attitudes, therefore, play an important mediating role [

23]. Yuan Wang’s researchers have studied migration through the movement of firms within a territory rather than through the movement of people. They argue that as globalisation deepens, cross-border corporate migration and investment are widespread. However, due to market orientation or cost orientation, many firms choose to migrate within their own territory, which has implications for capital flows, personnel, and changes in market structure [

24].

The research literature is rich in studies concerning population mortality [

25,

26], fertility, changes in family patterns [

27,

28], migration [

29] and ageing [

30]. However, there is a dearth of literature that examine changes in the working-age population in the context of these topics. Life expectancy, a probabilistic indicator of population mortality, is widely used to assess the health of the population and the overall level of social well-being [

25]. Mortality and social development theorists generally consider mortality and the structure of the causes of death to be a critical indicator of societal development, and sudden changes in the size and structure of the population are often associated with changes in mortality [

31].

Scientific literature [

16,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] points out that infrastructure is a key prerequisite for the development and needs of national, regional and urban economies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Studies and calculations by various researchers have shown that physical infrastructure correlates with GDP, labour productivity and investment [

38]. However, there is another side to the development of physical infrastructure. A study by the European Environment Agency (EEA) [

39] indicates that as much as 88% of Europe’s urban population is affected by pollution. Solutions to reduce air pollution are aimed at sustainable transport, i.e., transport services that justify the costs in terms of social needs and environmental protection and are optimally adapted to the needs of the city. Sustainable transport does not endanger public health or the ecosystem and ensures that long-term targets for renewable sources are met [

40]. Sustainable transport aims to ensure that environmental, social and economic factors influence all decisions related to the transport system [

41].

A safe environment is the only suitable medium in which the realisation and development of human rights and freedoms are possible. A sense of security determines individual behaviour and quality of life, as well as the social and political stability of the state and the confidence of the population in its legal and institutional mechanisms. Security is a multifaceted and relative category. Firstly, an individual, a state or a region can be secure or insecure. Secondly, the concept of security itself is vague and can be differentiated by object and domain, such as political security or road safety. As state governance becomes more complex and the social fabric of the state changes, the concept of security is also changing [

42].

One of the objectives of sustainable development is to eradicate poverty in all its dimensions in all countries, eradicate hunger, ensure food security and better nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. The relationship between the natural environment and poverty is a central theme in the sustainability and development literature [

43], and one that is gaining increasing attention among scholars [

44,

45,

46]. Research has been carried out at different dimensions, i.e., poverty alleviation through the promotion of entrepreneurship [

47] and local investment [

48].

Researchers [

49] have observed that social security benefits increase with average wages, while earnings increase with education and work experience, and have developed a model for measuring the social security system by combining: different skills, and qualifications.

2.2. In Lithuania

A smart society, according to the Lithuanian Progress Strategy 'Lithuania 2030,' is a happy society that strives for increased personal and economic security, equal income distribution, a healthier environment, social and political inclusion, excellent opportunities to learn and improve one’s skills, and good health. [

50]. Based on the same source, specific indicators are identified and Lithuania’s current position in relation to EU countries is compared:

Quality of life index (currently 23rd in the EU);

Happiness index (now ranked 20th in the EU);

Democracy Index (now 22nd in the EU);

Sustainable society index (now 13th in the EU).

The Social Progress Imperative, a US non-profit organisation, works with a strategic partner to calculate an annual social progress index. The index covers three groups: basic human needs, well-being and opportunities.

Table 1.

Social Progress Index 2022 (based on [

51]).

Table 1.

Social Progress Index 2022 (based on [

51]).

| Indicators |

Lithuania |

| Basic human needs |

88,56 |

| Foundations of wellbeing |

81,58 |

| Opportunity |

80,98 |

| Score |

83,71 |

| Rank |

29 |

According to the table, Lithuania ranks second among the Baltic States in terms of the Social Progress Index in 2022.

Analysing the quality of life indicators based on the data provided by the Lithuanian Department of Statistics, it is noted that the poverty risk level in 2021 fell by 0.9%, compared to 2020. The number of women in poverty was higher than men (22.4% and 17.1% respectively); however, the year-on-year change shows that the percentage of men in poverty decreased by 1.3% and the percentage of women by 0.7%. When analysed by age group, the highest percentage of the poor among both men and women was found in the 65+ age group, representing 24.3% of men in this age group and 42% of women. There are no significant differences between urban and rural poverty rates, with a uniform annual change of -0.9%.

The poverty rate for employed individuals is 7.5%, 0.5% less than in 2020.

The unemployment rate by all age groups and without distinction of place of residence, rural or urban, decreased by 0.6% in 2021. The highest unemployment rate by age group was between 15 and 24 years, i.e., 14.3%. The unemployment rate for men was higher than for women (7.6% and 6.6%, respectively). The unemployment rate in rural areas was higher than in urban areas (8.3% and 6.6%, respectively).

The percentage of young people who have dropped out of education has changed slightly (-0.2%); however, interestingly, in 2021, compared to 2020, the percentage of young people who have dropped out of education in urban areas has been increasing (0.9%), while it has been decreasing in rural areas (1.2%).

When analysing social indicators and indices over time, it can be seen that some are worsening whereas others are getting better. There are many reasons for this, but most notably, the modernisation of the country itself, which is a long and complex process involving different areas of the social environment, has a major impact on the creation of a coherent and sustainable social environment.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling Procedure

A representative survey of the Lithuanian population was undertaken between the 26th October and the 8th November 2022 by the Lithuanian-British market and public opinion research company Baltijos tyrimai (Baltic Research) according to a questionnaire agreed with the client. The survey involved 1,021 Lithuanians (aged 18 and over).

The findings of this survey are applicable to the Lithuanian population aged 18 and over. The survey was undertaken through individual interviews. The age range of this population was chosen in line with the EU’s practice of population opinion surveys (ESOMAR) and to compare the survey data with previous surveys on this topic.

Respondents for the population survey were selected using multi-stage stratified random sampling. There are several social groups that are not included in the sample of this study: persons in prison, persons in hospital and persons without a place of residence.

1,021 Lithuanians (aged 18 and over) participated in the survey. This sample allows for an optimum margin of error of no more than +- 3.1%.

The selection of respondents was undertaken in several stages:

Determining the proportion of respondents in the districts. This survey is carried out in all counties. The proportion of people interviewed in each county in the total sample corresponds to the proportion of the population aged 18 and over living in that county among the total population of that age in Lithuania;

The second stage is to determine the proportion of respondents in different size areas in each county. The categories of settlements used in this study are: Vilnius, large cities (over 50,000 inhabitants), towns (2,000 to 50,000 inhabitants), rural areas (up to 2,000 inhabitants). The number of respondents in the different sizes of each county corresponds to the proportion of the population aged 18 years and over living among the total population of that age in the county;

Third item. The third stage is the selection of specific settlements for the survey. From the list of settlements in each category (by population size) in each county, the localities to be surveyed are selected at random;

Respondents are selected using a purposive sampling method. In each community, a path is constructed by modifying a specific step in the selection of the residence where the survey is conducted. The responder at a particular household is chosen using the nearest birthday rule. Up to 3 attempts (visits) per interview are made. This principle of selection of respondents ensures maximum possible random sampling and equal probability of participation.

The survey took place between the 26th October and the 8th November 2022 at 116 sampling points (31 towns and 53 villages).

Demographic and social characteristics of the respondents (a total of 1,021 respondents aged 18 and over) are presented in

Table 2.

The survey data are compared across key socio-demographic dimensions (age, gender, income groups, settlement type, social status, and education). The margin of error for the results of this survey does not exceed 3.1% (with a 50% response rate) at 50%, with a confidence limit of 0.95 (see

Appendix A). The margin of error is calculated for a given sample size at a given response rate with a confidence level of 95%.

3.2. Research Techniques

The survey questionnaire consists of questions composed according to a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. According to the literature analysis 25 questions (statements) of the survey are composed.

First, descriptive statistics are performed to get a summary of the representation of the sample of a population. Furthermore, the mean and standard deviation of all variables in the items (constructs) are measured to analyse the variation and dispersion [

52].

Then, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM) are used as research techniques. These techniques are considered the most effective procedures to reveal latent items (constructs) with satisfactory reliability [

53,

54]. The three proposed hypotheses about the three constructs (factors) consisting of the measured variables are tested by the CFA method. Then SEM is used to assess these three theoretical constructs (latent factors) that cannot be directly measured by CFA.

The factor analysis technique is also used to group variables in several constructs (factors) and to check the eligibility of the selected variables for the research model. For this reason, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was estimated to avoid adverse effects on results. The estimates of VIF for all constructs are statistically sufficient if the degree of multicollinearity varies from 1 to 5. It means that the variables are moderately correlated [

55], and further research can be carried out.

The reliability of internal consistency is measured by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The value of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of a properly and qualitatively constructed item (factor) should be greater than 0.7 [

56], but less than 0.90 [

57]. The extracted average variance (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) indices are analysed to fit the discriminant validity [

58]. Also, it is necessary to avoid the problems of multicollinearity and singularity. For this purpose, the variables with insignificant and very strong correlation should be removed from the list of initial variables, that is, eliminate one selected from two variables whose mutual coefficient value is less than 0.2 and greater than 0.8 [

59].

SPSS 28.0 for the Windows statistical package and SPSS Amos software were used for CFA and SEM accordingly.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis of the Data

First, descriptive statistics were performed to get a summary of the representation of the sample of a population. There are no significant deviations between the mean and median of the variables.

69.8% (45.5 and 24.3 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that changes are needed in the Lithuanian education system. Similarly, 66.2% (43.7 and 22.5 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that innovative solutions are needed for changes to occur in Lithuanian education. 86% of the respondents believe that there are important aspects of education, such as diversity, creativity development, experience-based training, more options, communication, more order and rigor. However, 35.2% of the respondents believe that diversity is the most lacking in our education system, 20% creativity development, 16.8% experience-based training. 48% (42.2 and 5.8 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that there are suitable conditions for raising children in Lithuania.

46.4% (9.0 and 37.4 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents do not agree with the statement that in Lithuania, suitable infrastructure has been developed for the disabled in all areas of life, 32.9% – neither agree nor disagree. 42.9% (6.7 and 36.2 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents do not agree that there is a bad connection between Lithuania and other EU countries, 29.5% – neither agree nor disagree. 44.3% (6.7 and 36.2 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree with the statement that in Lithuania the connection between individual areas is not developed sufficiently and 27.2% neither agree nor disagree. 34.1% (29.4 and 4.7 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that the infrastructure of airports in Lithuania lags far behind the EU average, however, 30.2% – neither agree nor disagree. 35.3% (29.3 and 6.0 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree with the statement that too little attention is paid to traffic safety in Lithuania, and 30.8% – neither agree nor disagree. 29.9% (25.6 and 4.3 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that alternative fuels for cars are used too little in Lithuania, 35.7% – neither agree nor disagree. 45.5% (37.8 and 7.7 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that transport systems between big cities and suburbs are not well coordinated, 28.5% – neither agree nor disagree. 28.3% (25.2 and 3.1 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that the digital infrastructure is underdeveloped in Lithuania, 38.1% – neither agree nor disagree.

59.9% (51.5 and 8.4 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they are tolerant of other nationalities. 30.5% (26.7 and 3.8 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they follow the principles of a healthy lifestyle, however, 45.5% neither agree nor disagree. Although 53.7% (13.2 and 40.5 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents do not agree that they actively participate in cultural activities, moreover, 28.6% neither agree nor disagree. Similarly, 56.3% (15.2 and 41.1 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents do not agree that they are actively involved in community activities, and 25.5% neither agree nor disagree. 57.3% (16.3 and 41.0 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents do not agree that they actively participate in social activities, and 27.5% neither agree nor disagree.

4.2. Results of the CFA and SEM Analysis

Since the sample size is 1,021, and thus the sample is representative, these conditions help to eliminate additional checks and reduce the risk of inappropriate methods being used.

First, a factor analysis technique was used to the group variables (statements of the survey) into three constructs (factors). The significance of factor loadings of the variables is considered significant, since the sample size is greater than 1,000, so the factor should be greater than 0.162 [

60]. Furthermore, according to [

61] factor loadings less than 0.3 should be suppressed. Therefore, variables with factor loadings less than 0.3 were removed accordingly.

Second, the validity of the measurement instrument is verified using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient estimation method. As seen in

Table 3, the estimates of all Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are above the threshold limit of 0.7. This coefficient for each construct varies from 0.703 to 0.784. It means that the confidence rate of the variables is sufficient for research [

62,

63]. So, it is not necessary to improve the value of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each construct eliminating one of the variables. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the value of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire (the 18 questions were left after removing factor loading less than 0.3) is 0.760.

Third, AVE evaluated the convergent validity of each construct. The AVE values range from 0.502 to 0.522. Since the values of the AVE are greater than 0.5, the minimum requirement is reached [

57]. Also, the CR ranges from 0.795 to 0.860, so items (constructs) are considered to be matched with questions given to the respondents.

The CFA technique is also used to check the eligibility of the variables selected for the research model. Since the values of the VIF for all constructs are greater than 3 and less than 5, the variables are moderately correlated and there is no problem with collinearity [

58].

Table 3.

Factor loadings and reliability indicators.

Table 3.

Factor loadings and reliability indicators.

| Constructs and variables |

Factor loadings |

Cronbach’s alpha |

AVE |

CR |

VIF |

| Education system and educational culture |

|

0.703 |

0.507 |

0.795 |

3.642 |

| Changes are needed in the Lithuanian education system |

0.871 |

|

|

|

|

| Innovative solutions are needed for changes to occur in Lithuanian education |

0.853 |

|

|

|

|

| There are suitable conditions for raising children in Lithuania |

0.503 |

|

|

|

|

| How important are these aspects of education to you? |

0.537 |

|

|

|

|

| Social situation and socio-economic integration |

|

0.782 |

0.502 |

0.888 |

3.655 |

| In Lithuania, suitable infrastructure has been developed for the disabled in all areas of life |

0.651 |

|

|

|

|

| Currently, there is a bad connection between Lithuania and other EU countries |

0.684 |

|

|

|

|

In Lithuania, connection between individual

areas is insufficiently developed |

0.658 |

|

|

|

|

| The infrastructure of airports in Lithuania lags far behind the EU average |

0.648 |

|

|

|

|

| Too little attention is paid to traffic safety in Lithuania |

0.758 |

|

|

|

|

| Alternative fuels for cars are used too little in Lithuania |

0.694 |

|

|

|

|

| Transport systems between big cities and suburbs are not well coordinated |

0.672 |

|

|

|

|

| Digital infrastructure is underdeveloped in Lithuania |

0.871 |

|

|

|

|

| The legal system and public governance, and the importance of citizenship |

|

0.784 |

0.522 |

0.860 |

2.985 |

| I am tolerant of other nationalities |

0.502 |

|

|

|

|

| I follow the principles of healthy lifestyle |

0.569 |

|

|

|

|

| I actively participate in cultural activities |

0.841 |

|

|

|

|

| I am actively involved in community activities |

0.892 |

|

|

|

|

| I actively participate in social activities |

0.895 |

|

|

|

|

| Do you belong to any public organizations, associations, committees, societies or collectives? |

0.501 |

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, the unadjusted coefficient of determination R2 for the construct 'social environmental sustainability' is equal to 0.511 and is equivalent to 51.1% of variance, so it shows that 51.1% of the movement in the dependent variable can be explained by the independent variables.

From the methodological point of view, it was found that the social environmental sustainability of the respondents is a heterogeneous empirical construct (model), but it is composed of three different groups (constructs), which were given names summarizing the highlighted statements, taking into account the raised hypotheses.

The results of the SEM analysis supported the conceptual research model.

4. Discussion

The derived results of our research can clearly be separated into 2 different groups: of applied and theoretical significance. From the applied perspective we reveal that Lithuanian infrastructure is relatively inadequate for the development of the modern society, as statements such as 'Changes are needed in the Lithuanian education system' and 'Innovative solutions are needed for changes to occur in Lithuanian education' show very high means 4.57 and 4.66, respectively. Additionally, the statement 'There are suitable conditions for raising children in Lithuania' received quite a low score, 3.56. These findings correspond to [

64] insights into the outdated nature of student education practices in Lithuania. It also echoes [

65] call for a more rapid implementation of innovations in the Lithuanian educational system. Although there is also a new insight. It is revealed that people associate suitable conditions for raising children not only with economic factors, as was assumed [

66,

67,

68], but also with the level of education state is able to provide. This insight may be of high value to the government or other decision makers when considering policies aimed at increased its citizens well-being [

69] and achieving a welfare state status [

70]. It should be mentioned that this insight is also of particular importance due to the fact that the Lithuanian society is characterised by a high degree of paternalism [

71], and expects the state to take care of a number of factors that affect their quality of life, which are typically assigned to the citizen’s personal responsibility. From the theoretical standpoint we enhance the notions of the education system and educational culture proposing to include various micro-economic factors associated with the quality of life of citizens when analysing the quality of the educational culture in the country. As revealed, citizens clearly associate the conditions for raising children with the educational system / culture of the state.

Analysing the modernisation of the country through the lens of socio-economic inte-gration, it was revealed that although extensively researched [

72,

73,

74,

75], at least in Lithuania the integration of the disabled persons into the society did not play a significant part in the modernisation of the state. This once again confirms the statements about the unsatisfactory situation with the integration of various vulnerable societal groups into the public life in Lithuania [

76]. It is an interesting finding, which contradicts a little a statement about being tolerant. This discrepancy can also be a prospective research direction, as it would be useful to determine why persons, who consider themselves tolerant to various immigrant communities, find an integration of the disabled persons not a very important issue. The revealed importance of the transport infrastructure in the modernization of the Lithuanian state can easily be explained. The developed road and air connection with western European countries not only allows more easy travel for the labour migrant, which when sends remittances to their relatives within the country contributing to their standards of living, which are one of the pre-requisites for the modern country [

77]. Another aspect that emphasizes the importance of travel infrastructure in the modernisation of the country is the flow of ideas and the cultural background. Infrastructure enables people to travel and bring Western thinking patterns [

78]. It is even argued that this type of cultural diffusion serves the modernisation of the country even more than the adoption of European legal norms and practices [

79,

80]. Today, the biggest amounts of information are being shared online [

81]. Social networks are even considered the main source of information that people use, even to their most important decisions [

82]. The underdeveloped IT infrastructure revealed may be considered to be one of the main obstacles to continuous modernisation of the country [

83].

Analysing the importance of public administration and citizenship, one can notice quite low scores of public participation in Lithuania. It is an important finding that can explain the relatively low trust in government [

71], which, in turn, is reflected in the increasing mistrust among various social groups within the society [

84]. This revealed issue also has applied and theoretical implications. It is suggested to increase civic participation not only to increase local social cohesion, as assumed [

85], but also to increase the perceived legitimacy of government actions in the eyes of its citizens [

86]. From a scientific point of view, this is also an important finding. Until now it has been considered that a modern society can hardly be achieved without high public / civic participation [

87,

88,

89,

90]. Lithuania is considered a developed and modern state [

91], although, as our research shows, its citizens perceive public participation as not a very important factor in the emergence of the modern state. The relative factor importance of the item 'I actively participate in social activities' compared to 'Do you belong to any public organizations, associations, committees, societies, or collectives? ' may confirm [

71] insights about the perceived social distance between government and citizens in Lithuania, which manifests itself through low public participation.

5. Conclusions

The revealed importance of the socio-economic sustainability in the formation of modern society suggests a new approach when assessing the emergence of knowledge society [

19]. The main novelty of our research is the proposition of a framework for the assessment of the socio environmental sustainability from the eyes of its citizens. It allows to supplement the widely accepted 'hard' indicators of social environmental indicators [

92,

93] with 'soft' ones reflecting the perceptions of citizens.

Our research confirmed that the analysis of the country’s modernisation from the perspective of social environmental sustainability should be carried out from three perspectives, namely through the lens of education system and educational quality; socio-economic integration; the legal system and public administration and citizenship. We show that the assessment of the quality of education of the country should be a multi-faceted evaluation that also includes various micro-economic indicators that measure the standards of living in the country. A revealed relative negligence of Lithuanians toward the integration of the disabled serves as one of the hindering factors toward continuous socio-economic modernisation of the state. Another factor that impedes further development of the Lithuanian society is low engagement in public participation.

One of the limitations of our study lay in the fact that we have researched only 'soft' indicators reflecting the socio economic sustainability, i.e., without the 'hard' ones. Research combining both groups of indicators may produce slightly different results. Such a research could be named as a prospective research direction.

The revealed future research directions also could be aimed at investigating factors that lead to the fact that people consider themselves tolerant toward various immigrant groups present in their country, although they show relative disregard for the needs of disabled citizens of their own country. Another avenue of prospective research is associated with further investigation of the overlooked factors that have an impact on the perceived quality of the educational culture of the country. The revealed importance of some economic indicators allow us to presume that there are more peripheral components which in the eyes of the citizens have impact on the level of educational culture within the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; methodology, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; software, O.N.; validation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; formal analysis, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; investigation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; resources, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; data curation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; visualization, O.N., I.M.-K., R.C., M.M. and A.V.; supervision, O.N.; project administration, O.N.; funding acquisition, O.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under project agreement No S-MOD-21-10. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Calculation Table of Answers Errors.

Table A1.

Calculation Table of Answers Errors.

| Sample size (n) |

|---|

| Responses (%) |

10 |

40 |

75 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

300 |

350 |

400 |

450 |

500 |

600 |

700 |

800 |

900 |

1000 |

| 0.1 |

1.95 |

0.98 |

0.72 |

0.62 |

0.51 |

0.44 |

0.39 |

0.36 |

0.33 |

0.31 |

0.29 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.23 |

0.22 |

0.21 |

0.20 |

| 0.5 |

4.37 |

2.19 |

1.60 |

1.38 |

1.13 |

0.98 |

0.87 |

0.80 |

0.74 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.62 |

0.56 |

0.52 |

0.49 |

0.46 |

0.44 |

| 1.0 |

6.17 |

3.08 |

2.25 |

1.95 |

1.59 |

1.38 |

1.23 |

1.13 |

1.04 |

0.98 |

0.92 |

0.87 |

0.80 |

0.74 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.62 |

| 2.0 |

8.68 |

4.34 |

3.17 |

2.74 |

2.24 |

1.94 |

1.74 |

1.58 |

1.47 |

1.37 |

1.29 |

1.23 |

1.12 |

1.04 |

0.97 |

0.91 |

0.87 |

| 3.0 |

10.57 |

5.29 |

3.86 |

3.34 |

2.73 |

2.36 |

2.11 |

1.93 |

1.79 |

1.67 |

1.58 |

1.50 |

1.36 |

1.26 |

1.18 |

1.11 |

1.06 |

| 4.0 |

12.15 |

6.07 |

4.43 |

3.84 |

3.14 |

2.72 |

2.43 |

2.22 |

2.05 |

1.92 |

1.81 |

1.72 |

1.57 |

1.45 |

1.36 |

1.28 |

1.21 |

| 5.0 |

13.51 |

6.75 |

4.93 |

4.27 |

3.49 |

3.02 |

2.70 |

2.47 |

2.28 |

2.14 |

2.01 |

1.91 |

1.74 |

1.61 |

1.51 |

1.42 |

1.35 |

| 6.0 |

14.72 |

7.36 |

5.37 |

4.65 |

3.80 |

3.29 |

2.94 |

2.69 |

2.49 |

2.33 |

2.19 |

2.08 |

1.90 |

1.76 |

1.65 |

1.55 |

1.47 |

| 7.0 |

15.81 |

7.91 |

5.77 |

5.00 |

4.08 |

3.54 |

3.16 |

2.89 |

2.67 |

2.50 |

2.36 |

2.24 |

2.04 |

1.89 |

1.77 |

1.67 |

1.58 |

| 8.0 |

16.81 |

8.41 |

6.14 |

5.32 |

4.34 |

3.76 |

3.36 |

3.07 |

2.84 |

2.66 |

2.51 |

2.38 |

2.17 |

2.01 |

1.88 |

1.77 |

1.68 |

| 9.0 |

17.74 |

8/87 |

6.48 |

5.61 |

4.58 |

3.97 |

3.55 |

3.24 |

3.00 |

2.80 |

2.64 |

2.51 |

2.29 |

2.12 |

1.98 |

1.87 |

1.77 |

| 10.0 |

18.59 |

9.30 |

6.79 |

5.88 |

4.80 |

4.16 |

3.72 |

3.39 |

3.14 |

2.94 |

2.77 |

2.63 |

2.40 |

2.22 |

2.08 |

1.96 |

1.86 |

| 15.0 |

22.13 |

11.07 |

8.08 |

7.00 |

5.71 |

4.95 |

4.43 |

4.04 |

3.74 |

3.50 |

3.30 |

3.13 |

2.26 |

2.65 |

2.47 |

2.33 |

2.12 |

| 20.0 |

24.79 |

12.40 |

9.05 |

7.84 |

6.40 |

5.54 |

4.96 |

4.53 |

4.19 |

3.92 |

3.70 |

3.51 |

3.20 |

2.96 |

2.77 |

2.61 |

2.48 |

| 25.0 |

26.84 |

13.42 |

9.80 |

8.49 |

6.93 |

6.00 |

5.37 |

4.90 |

4.54 |

4.24 |

4.00 |

3.80 |

3.46 |

3.21 |

3.00 |

2.83 |

2.68 |

| 30.0 |

28.40 |

14.20 |

10.37 |

8.98 |

7.33 |

6.35 |

5.68 |

5.19 |

4.80 |

4.49 |

4.23 |

4.02 |

3.67 |

3.39 |

3.18 |

2.99 |

2.84 |

| 35.0 |

29.56 |

14.78 |

10.79 |

9.35 |

7.63 |

6.61 |

5.91 |

5.40 |

5.00 |

4.67 |

4.41 |

4.18 |

3.82 |

3.56 |

3.31 |

3.12 |

2.96 |

| 40.0 |

30.36 |

15.18 |

11.09 |

9.60 |

7.84 |

6.79 |

6.07 |

5.54 |

5.13 |

4.80 |

4.53 |

4.29 |

3.92 |

3.63 |

3.39 |

3.20 |

3.04 |

| 45.0 |

30.83 |

15.42 |

11.26 |

9.75 |

6.89 |

6.89 |

6.17 |

5.63 |

5.21 |

4.88 |

4.60 |

4.36 |

3.98 |

3.69 |

3.45 |

3.25 |

3.08 |

| 50.0 |

30.99 |

15.50 |

11.32 |

9.80 |

8.00 |

6.93 |

6.20 |

5.66 |

5.24 |

4.90 |

4.62 |

4.38 |

4.00 |

3.70 |

3.46 |

3.27 |

3.10 |

References

- N. Jafari, M. Azarian, H. Yu; Moving from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: What Are the Implications for Smart Logistics? Logistics, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 26, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Apie EST,” [Online]. Available: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/about/country/lithuania/.

- D. Marcinkevičienė, Sovietmečio istoriografija: užsienio autorių tyrinėjimai ir interpretacijos, 2005.

- M. R. BAIRAŠAUSKAITĖ Tamara, MEDIŠAUSKIENĖ Zita, AR PAVYKO (PAVYKS) ATSKLEISTI MODERNĖJIMĄ LIETUVOS MODERNĖJIMO ISTORIJOJE? 2011.

- M. Nefas, Modernioji Lietuva tarpukariu: tarp pažangos ir laimėjimų, Istorija, vol. 106, no. 2, pp. 126–131, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Hout, “Classical Approaches to Development: Modernisation and Dependency,” in The Palgrave Handbook of International Development, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016, pp. 21–39.

- LIETUVOS RESPUBLIKOS VYRIAUSYBĖ, “NUTARIMAS DĖL 2021–2030 METŲ NACIONALINIO PAŽANGOS PLANO PATVIRTINIMO,” 2020. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/c1259440f7dd11eab72ddb4a109da1b5?jfwid=32wf90sn.

- J. Pivorienė, “Global Education and Social Dimension of Sustainable Development,” Soc. Ugdym., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 39–47, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Marin, R. Dorobanţu, D. Codreanu, and R. Mihaela, “The Fruit of Collaboration Between Local Government and Private Partners in the Sustainable Development Community Case Study: County Valcea,” Acad. Econ. Stud. Rom., vol. 15, no. 2/2012, pp. 93–98, 2012, [Online]. Available: www.ugb.ro/etc.

- L.-I. Cioca, L. Ivascu, E. Rada, V. Torretta, and G. Ionescu, “Sustainable Development and Technological Impact on CO2 Reducing Conditions in Romania,” Sustainability, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1637–1650, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Klarin, “The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues,” Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 67–94, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, Social sustainability: A review and critique of traditional versus emerging themes and assessment methods. 2009.

- S. Panda, M. Chakraborty, and S. K. Misra, “Assessment of social sustainable development in urban India by a composite index,” Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 435–450, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Činčikaitė and N. Paliulis, “Assessing Competitiveness of Lithuanian Cities,” Econ. Manag., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 490–500, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Andrea Colantonio, “Measuring Socially Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Europe,” 2009.

- C. Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S.éad, & Brown, “The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability.,” Sustain. Dev., vol. 19(5), 2011.

- J. Bruneckienė, “Šalies Regionų Konkurencingumo Vertinimas Įvairiais Metodais: Rezultatų Analizė Ir Vertinimas,” Econ. Manag., vol. 15, pp. 25–31, 2010, [Online]. Available: http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=5&sid=46d29dc4-d367-454e-a17f-0384733d0561%40pdc-v-sessmgr06&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3D%3D#AN=53172840&db=bsu.

- V. Snieška and I. Zykiene, “The Role of Infrastructure in the Future City: Theoretical Perspective,” Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci., vol. 156, pp. 247–251, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Melnikas, “Urbanizacijos procesai šiuolaikinių globalizacijos, Europos integracijos ir žinių visuomenės kūrimo iššūkių kontekste,” A Theor. Pract. J., vol. 2, no. 38, pp. 23–41, 2013.

- J. Poot, “Demographic Change and Regional Competitiveness: The Effects of Immigration and Ageing.,” Popul. Stud. Cent., p. 17, 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. Činčikaitė and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “Assessment of Social Environment Competitiveness in Terms of Security in the Baltic Capitals,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 6932, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Karolis Žibas, “DARBO MIGRACIJOS PROCESAI LIETUVOJE,” vol. 6, pp. 54–69, 2017.

- Y. Zhang, T. Jiang, J. Sun, Z. Fu, and Y. Yu, “Sustainable Development of Urbanization: From the Perspective of Social Security and Social Attitude for Migration,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 17, p. 10777, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Y. Liang, Y. Wang, Z. Li, and C. Guo, “Redistribution of Resources: Sustainable System Mechanisms for Enterprise Migration,” Sci. Program., vol. 2022, pp. 1–17, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Grigoriev, P., Jasilionis, D., Stumbrys, D., Stankūnienė, V. and Shkolnikov, “Individualand area-level characteristics associated with alcohol-related mortality among adult Lithuanian males: A multilevel analysis based on census-linked data.,” PLoS One, 2017.

- Jasilionis, D., Stankūnienė, V., Maslauskaitė, A., Stumbrys, D., Lietuvos demografinių procesų diferenciacija, 2015.

- Stankūnienė, V., Baublytė, M., Žibas, K. and Stumbrys, D., “Lietuvos demografinė kaita. Ką atskleidžia gyventojų surašymai.,” 2016.

- M. Stankūnienė, V., Maslauskaitė, A. and Baublytė, “Ar Lietuvos šeimos bus gausesnės?,” Liet. Soc. Tyrim. Centras, 2013.

- Klüsener, S., Stankūnienė, V., Grigoriev, P. and Jasilionis, D., “Emigration in a Mass Emigration Setting: The Case of Lithuania,” Int. Migr., vol. 4, pp. 1–15, 2015.

- S. Kanopienė, V. and Mikulionienė, “Gyventojų senėjimas ir jo iššūkiai sveikatos apsaugos sistemai.,” Gerontologija, pp. 188–200, 2006.

- S. Daumantas, “DEMOGRAFINIŲ POKYČIŲ ĮTAKA LIETUVOS DARBO IŠTEKLIAMS,” no. 6, pp. 11–22, 2017.

- Newman, B. Cooper, P. Holland, Q. Miao, and J. Teicher, “How do industrial relations climate and union instrumentality enhance employee performance? The mediating effects of perceived job security and trust in management,” Hum. Resour. Manage., vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 35–44, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ž. Remigijus Čiegis, “DARNUS MIESTŲ VYSTYMASIS IR EUROPOS SĄJUNGOS INVESTICIJŲ ĮSISAVINIMAS,” Manag. theory, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 42–51, 2012.

- J. Sinkienė, Miesto konkurencingumo veiksniai, Viešoji Polit. ir Adm., no. 25, pp. 68–83, 2008, [Online]. Available: http://archive.minfolit.lt/arch/17501/17732.pdf.

- J. Bruneckiene, R. Činčikaitė, and A. Kilijonienė, “The Specifics of Measurement the Urban Competitiveness at the National and International Level,” Eng. Econ., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 256–270, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Činčikaitė and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “An Integrated Competitiveness Assessment of the Baltic Capitals Based on the Principles of Sustainable Development,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 3764, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Vitkūnas, R. Činčikaitė, and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “Assessment of the Impact of Road Transport Change on the Security of the Urban Social Environment,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12630, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- North Atlantic Marine Mammals Commission, Annual Report 2005. 2005.

- European Environment Agency, Environmental Indicator Report 2012—Ecosystem Resilience and Resource Efficiency in a Green Economy in Europe. 2013.

- OECD Annual Report 2000. OECD, 2000.

- T. Litman, “Exploring the Paradigm Shifts Needed to Reconcile Transportation and Sustainability Objectives,” Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board, vol. 1670, no. 1, pp. 8–12, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija, Borisas Melnikas, Vladas Tumalavičius, Alvydas Šakočius, Mantas Bileišis, Svajūnė Ungurytė-Ragauskienė, Vidmantė Giedraitytė, Dalia Prakapienė, Jūratė Guščinskienė, Jadvyga Čiburienė, Gediminas Dubauskas, Saugumo iššūkiai: saugumo iššūkiai: 2020.

- J. Schleicher, M. Schaafsma, and B. Vira, “Will the Sustainable Development Goals address the links between poverty and the natural environment?” Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain., vol. 34, pp. 43–47, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Helne and T. Hirvilammi, “Wellbeing and Sustainability: A Relational Approach,” Sustain. Dev., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 167–175, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Díaz et al., “The IPBES Conceptual Framework — connecting nature and people,” Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain., vol. 14, pp. 1–16, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. J. MILNER-GULLAND et al., “Accounting for the Impact of Conservation on Human Well-Being,” Conserv. Biol., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 1160–1166, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu and S. Si, “Poverty reduction through entrepreneurship: incentives, social networks, and sustainability,” Asian Bus. Manag., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 243–259, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu; Y. Wang, Rural land engineering and poverty alleviation: Lessons from typical regions in China, J. Geogr. Sci., vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 643–657, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Akizu-Gardoki et al., Decoupling between human development and energy consumption within footprint accounts, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 202, pp. 1145–1157, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Valstybės pažangos strategija „Lietuvos pažangos strategija „LIETUVA 2030“”. Lithuania: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.425517, 2012.

- M. Stern, S., Harmacek, J., Krylova, P. Htitich, 2022 Social Progress Index® Methodology Report, 2022, [Online]. Available: http://www.estuaries.org/.

- Andrew F. Siegel, Michael R. Wagner, in Practical Business Statistics (Eighth Edition), 2022.

- Lee, S.-Y. Handbook of Latent Variable and Related Models. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/North-Holland, 2007.

- Woods, C.M.; Edwards, M.C. Factor Analysis and Related Methods. Essential Statistical Methods for Medical Statistics; Rao, C.R., Miller, J.P, B., Rao, D.C.; Elsevier: North-Holland, 2011; Volume 27, pp. 174–201.

- Knoke, D.; Bohrnstedt, W.G.; Mee, A.P. Statistics for social data analysis, 4th ed.; F.E. Peacock Publisher: Illinois, 2002.

- DeVellis, R. Scale development: theory and applications: theory and application. Sage: Thousand Okas, CA, 2003.

- Streiner, D. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of personality assessment 2003, 80, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., Ray, S. (2021). Evaluation of Reflective Measurement Models. In: Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering statistics using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, 2005.

- Stevens, J.P. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002.

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS, 4th ed. London: SAGE, 2013.

- Aiken, L. R. Psychological testing and assessment, 11th ed.; Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002.

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of medical education, 2011, 2, 53–55.

- Raudienė, I., Kaminskienė, L., & Cheng, L. (2022). The education and assessment system in Lithuania. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 29(3), 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Kasperavičiūtė-Černiauskienė, R., & Serafinas, D. (2018). The adoption of ISO 9001 standard within higher education institutions in Lithuania: innovation diffusion approach. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(1-2), 74-93. [CrossRef]

- Parish, S. L., Shattuck, P. T., & Rose, R. A. (2009). Financial burden of raising CSHCN: association with state policy choices. Pediatrics, 124(Supplement_4), S435-S442. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, D., Savage, A., & Breitkreuz, R. (2014). Resilience in families raising children with disabilities and behavior problems. Research in developmental disabilities, 35(4), 833-848. [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 198-223.

- Martela, F., & Sheldon, K. M. (2019). Clarifying the concept of well-being: Psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Review of General Psychology, 23(4), 458-474. [CrossRef]

- Robson, W. A. (2018). Welfare state and welfare society: illusion and reality. Routledge.

- Morkūnas, M. (2022). Russian Disinformation in the Baltics: Does it Really Work?. Public Integrity, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2020). Integrating disability, transforming feminist theory. In Feminist Theory Reader (pp. 181-191). Routledge.

- Vornholt, K., Villotti, P., Muschalla, B., Bauer, J., Colella, A., Zijlstra, F., ... & Corbière, M. (2018). Disability and employment–overview and highlights. European journal of work and organizational psychology, 27(1), 40-55.

- Rolland, J. S. (2018). Helping couples and families navigate illness and disability: An integrated approach. Guilford Publications.

- Bonaccio, S., Connelly, C. E., Gellatly, I. R., Jetha, A., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2020). The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: Employer concerns and research evidence. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(2), 135-158. [CrossRef]

- Jurkuvienė, R., Danusevičienė, L., Butkevičienė, R., & Gajdosikienė, I. (2016). The process of creating integrated home Care in Lithuania: from idea to reality. International journal of integrated care, 16(3). [CrossRef]

- Kharazishvili, Y., Kwilinski, A., Grishnova, O., & Dzwigol, H. (2020). Social safety of society for developing countries to meet sustainable development standards: Indicators, level, strategic benchmarks (with calculations based on the case study of Ukraine). Sustainability, 12(21), 8953. [CrossRef]

- Surman, J., & Petushkova, D. (2022). Between Westernization and Traditionalism: Central and Eastern European Academia during the Transformation in the 1990s. Studia Historiae Scienfiarum21, 435-483. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M. W., Knill, C., & Pitschel, D. (2007). Differential Europeanization in Eastern Europe: the impact of diverse EU regulatory governance patterns. Journal of European Integration, 29(4), 405-423. [CrossRef]

- Carmin, J., & VanDeveer, S. D. (Eds.). (2005). EU enlargement and the environment: institutional change and environmental policy in Central and Eastern Europe (Vol. 9). Psychology Press.

- Kim, J., & Hastak, M. (2018). Social network analysis: Characteristics of online social networks after a disaster. International journal of information management, 38(1), 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Jost, J. T., Barberá, P., Bonneau, R., Langer, M., Metzger, M., Nagler, J., ... & Tucker, J. A. (2018). How social media facilitates political protest: Information, motivation, and social networks. Political psychology, 39, 85-118. [CrossRef]

- Tvaronavičienė, M., Plėta, T., Della Casa, S., & Latvys, J. (2020). Cyber security management of critical energy infrastructure in national cybersecurity strategies: Cases of USA, UK, France, Estonia and Lithuania. Insights into regional development, 2(4), 802-813. [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. M. (2020). Mistrust, uncertainty and health risks. Contemporary Social Science, 15(5), 504-516. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V., & Bamkole, O. (2019). The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(3), 452. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Beyond celebrity politics: Celebrity as governmentality in China. Sage Open, 10(3), 2158244020941862. [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D., & Schweizer, P. J. (2021). Public values and goals for public participation. Environmental Policy and Governance, 31(4), 257-269. [CrossRef]

- Lovenduski, J., & Hills, J. (Eds.). (2018). The Politics of the Second Electorate: Women and Public Participation: Britain, USA, Canada, Australia, France, Spain, West Germany, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Eastern Europe, USSR, Japan. Routledge.

- Campagna, D., Caperna, G., & Montalto, V. (2020). Does culture make a better citizen? Exploring the relationship between cultural and civic participation in Italy. Social Indicators Research, 149(2), 657-686. [CrossRef]

- Harahap, A. M., & Lybeshari, A. (2021). Civic Engagement in MENA States: An Islamic Exegetical and Historical Inquiry. Review on Globalization: From An Islamic Perspective, 9.

- Balezentis, T., Morkunas, M., Volkov, A., Ribasauskiene, E., & Streimikiene, D. (2021). Are women neglected in the EU agriculture? Evidence from Lithuanian young farmers. Land use policy, 101, 105129. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. K., Negi, M., Nandy, S., Kumar, M., Singh, V., Valente, D., ... & Pandey, R. (2020). Mapping socio-environmental vulnerability to climate change in different altitude zones in the Indian Himalayas. Ecological Indicators, 109, 105787. [CrossRef]

- Chandrakumar, C., & McLaren, S. J. (2018). Towards a comprehensive absolute sustainability assessment method for effective Earth system governance: Defining key environmental indicators using an enhanced-DPSIR framework. Ecological Indicators, 90, 577-583. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).