1. Introduction

Cervical Cancer (CC) is a malignant tumor that causes an abnormal and disordered proliferation of epithelial cells in the transformation zone of the cervix. It is a sexually transmitted disease caused by an infectious pathogen called human papillomavirus (HPV) (1). It is the fourth most common type of cancer (2) and third leading cause of cancer death (3) of women around the world. In 2020, globally around 604127 new cases and 341,831 deaths of cervical cancer were recorded (2). Additionally, it is anticipated that by 2030, there may be an additional 40000 fatalities and 70000 new cases of the disease all around the world (4). About 8,268 new cervical cancer cases are diagnosed annually in Bangladesh (estimations for 2020). According to the global cancer estimated report in 2020, the incidence and mortality rate of cervical cancer in Bangladesh were respectively 10.6 and 6.7 per 100,000 women including age-standardized rates (5). In Bangladesh, both the occurrence and mortality rate patterns have shifted upward over the period in which 4,971 women die and 8,268 women are diagnosed with CC every year (6). Though it is a most successfully treatable forms of cancer even in later stage (2), most deaths recorded in low- to middle income countries due to significant disparities in incidence and mortality (7,8).

There could be several risk factors responsible for causing cervical cancer in humans including food habits, obesity, nutrient deficiency, and sexual history (39, 40). Furthermore, low healthcare facilities, lack of awareness about its symptoms and risk factors, screening programs, and preventive measures could also play important role. Moreover, social acceptance, social taboos, stigma and ignorance of people eventually makes them delay to take proper treatment and lead them to death [

15,

18]. Apart from that, other risks are associated with marriage at an early age, multiple sexual partners, prolonged use of oral contraceptive pills, multiple childbirths, immune suppressants, and specific dietary factors (9). Abstinence the number of sexual partners, and consistent condom use can reduce the risk of HPV infection (10) but does not eliminate the risk, as the virus is spread via skin contact (11). On the other hand, male circumcision had found as a protective factor against HPV infection (12).

Effective vaccination is the primary effort for prevention HPV followed by screening for, and treating precancerous lesions (2). WHO has set target of vaccinating 90% of all girls by age 15 years, screening 70% of women twice in the age range of 35–45 years, and treating at least 90% of all precancerous lesions in order to reduce the incidence rate of cervical cancer (13). Since November 2006, the quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) that protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 have been included in the Vaccines for Children Program in the United States. In 2009, FDA approved Cervix, another HPV vaccine that has shown protection against HPV type 45 and HPV type 31 in addition to HPV 16 and HPV 18. In the South of Mexico, the tetravalent vaccine could potentially prevent 78% of cervical carcinoma cases (12). Furthermore, the HPV 16/18 vaccines are estimated to provide 67% protection against invasive cervical carcinoma (ICC) in Asia (14). In 2016 for the first time in Bangladesh, the Ministry of Health, with support from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) has been introduced the HPV vaccine (15).

In the last few years, the Bangladesh government is promoting cervical cancer screening facilities in all districts and sub-district levels. About 400 screening facilities covered less than 10% of cervical cancer (9,16). The National Strategy for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Bangladesh (2017–2022) was targeting to reinforce the ongoing National Cervical Cancer Control Program. Moreover, collaborating with the existing Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI), the National Strategy makes it intuitive to introduce vaccination to fight against the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) among adolescent girls in Bangladesh (16).

Despite all efforts cervical cancer exists as the second most common female cancer in middle aged women mostly 15 to 44 years in Bangladesh (17). It was estimated that 95% of women in developing countries had never been screened for cervical cancer (CCa) mainly due to a lack of awareness in the community (7). Literature determined that the poor knowledge of people is an important cause of higher prevalence of cervical cancer in Bangladesh (6). However, the knowledge and awareness of an individual is influenced by various socio-demographic factors including gender, age, education level, religion etc. as well as the source of information. Previous studies showed mass media was the major source of information of community (3).

In Bangladesh, awareness about HPV infection is very low among the general population as well as healthcare professionals and policymakers (13). Therefore, our study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitude toward human papillomavirus, cervical cancer, and vaccination among young female students in Chittagong, Bangladesh. The study will provide baseline information to support an evidence-based communication strategy in order to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer.

2. Methodology

Study design

This cross-sectional survey had conducted among female students studying at the Asian University for Women in Chattogram city of Bangladesh. Both married and unmarried students were reached to participate. A non-probability convenient sampling technique was used to select students. We targeted students only from public health department studying at different batches at the undergraduate level. We excluded all post-graduate students. A total of 300 students were approached to participate in the study. The study was carried out between December 2020 and June 2021

Questionnaire design and data collection

A semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection to achieve the objectives of the study. A comprehensive literature review was performed to design the questionnaire. The language of the questionnaire was English. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews of students by the primary researcher to avoid any sort of biases. The questionnaire possessed information on the socio-demographic characteristics of students, reproductive history, knowledge about the Human Papillomavirus, source of information, risk factors of cervical cancer, clinical signs, and screening for cervical cancer. In addition, it included questions on the perception of students towards vaccination and other preventive measures of cervical cancer. The questionnaire was pre-tested among a small group of students and revised before the finalization. Most of the questions were close-ended with ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ answers. Few questions were multiple-choice types and participants were allowed to choose more than one answer. This survey was conducted mostly similar to an interview. Moreover, every question was asked by the primary researcher to avoid all sorts of biases.

Data management and analysis

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 20; IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Composite scores related to knowledge of cervical cancer and prevention strategies were calculated and compared among the sub-groups. The students who provided correct answers were given one score and marked with zero scores for not knowing or giving the wrong answers. Participants were categorized as having good and poor knowledge based on their responses. Participants possessing a total score of five to eight were considered to have had “Good knowledge”, on the other hand, participants with none to four scores were marked under the “Poor knowledge” category. The sociodemographic variables were considered indicator variables whereas the level of knowledge was considered an outcome variable. Variables were summarized by using descriptive statistics and presented in tables and figures. Pearson’s Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests were used to assess the associations between students’ socio-demographic variables and their level of knowledge. Finally, binary logistic regression analysis was done to understand factors related to having better knowledge and intention of having a vaccine or screening test when needed.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted following the Asian University for Women’s (AUW) ethical guidelines. Before starting the interview, respondents were given detailed information regarding the study's purpose and informed consent was taken from each participant. Moreover, all the participants have been assured that confidentiality will be maintained strictly and the data will be used for research purpose only. Participants had the right to leave the study at any time.

3. The knowledge level of students and association with socio-demographic variables

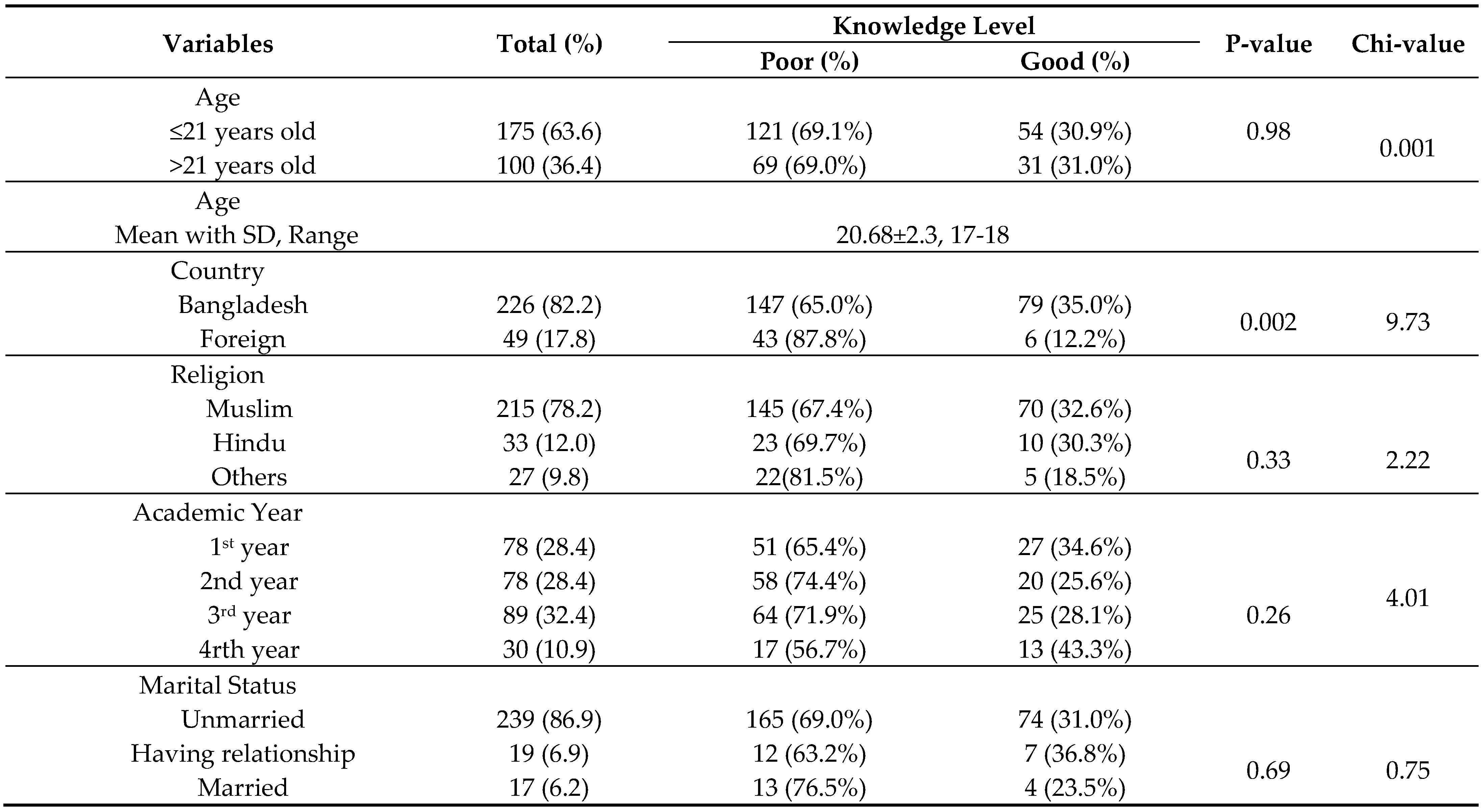

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants and compare with their corresponding knowledge levels. Among all variables, the country of participants had a significant association with their knowledge level. In total, 63.6% of the participants were aged ≤21 years whereas 36.4% of them were older than 21 years with a mean age of 20.68 years. The majority of them aged ≤21 years old (69.1%) or more than 21 years old (69.0%) possessed poor knowledge regarding cervical cancer. Among the total, 35.0% Bangladeshi and 12.2% foreign students had good knowledge of cervical cancer with a significant p-value of 0.002.

Although Muslim students were higher (78.2%) than Hindus (12%) the proportion of them was almost equal (32.6% Muslim and 30.3% Hindu) under the good knowledge category Overall, most of the participants who has a higher education (final year) showed good knowledge (43.3%). Higher levels of good knowledge were found among unmarried (31%) and students having relationships (36.8%) than married students (23.5%).

Table 2 observe that the mean score was 3.61 with a standard deviation of 1.9. In this regard, the highest percentage of participants (69.1%) were ranked poor in compared to good rank (30.9%).

Table 3 indicates the source of information marked by the students. Most of them (49.8%) were heard about cervical cancer from traditional media like newspaper/television followed by 33.5% from social media and 30.9% from their doctor, Besides, higher proportion of participants having good knowledge was getting information from physician (49.4%). The effect of traditional media and physician was statistically significant on the knowledge level of students.

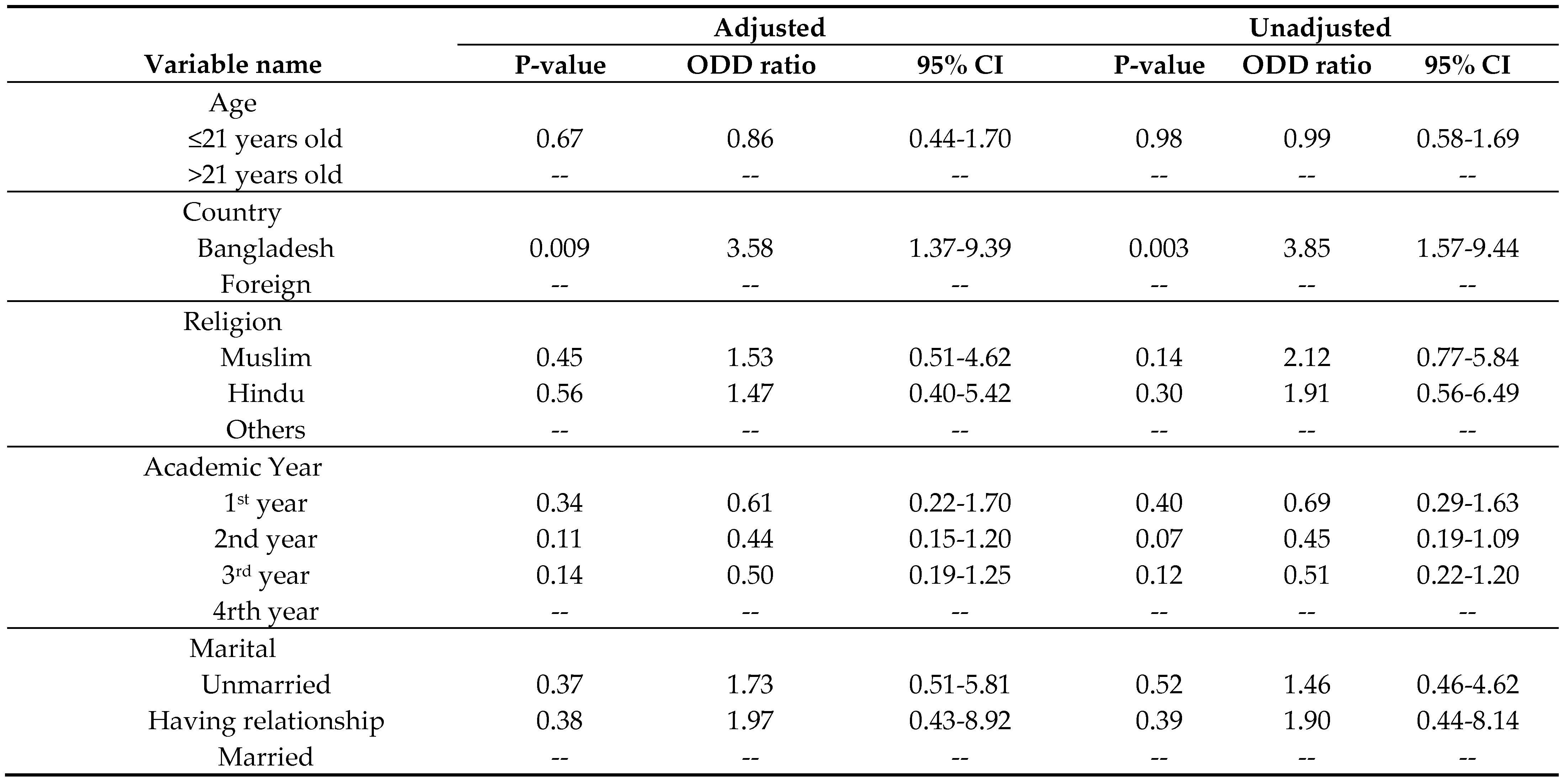

Table 4 illustrates the result of binary logistic regression where it was revealed that, the students who were living in Bangladesh were 3.85 times (CI=1.57-9.44; p value=0.003) more knowledgeable than the respondents living in other foreign countries. Furthermore, participants who were Muslim by religion had 2.12 times (CI=0.77-5.84) more knowledge than the people who follow other religions. In addition to that, unmarried respondents were reported to have had 1.46 times more knowledge (CI=0.46-4.62) than the people who are having relationships or who are married.

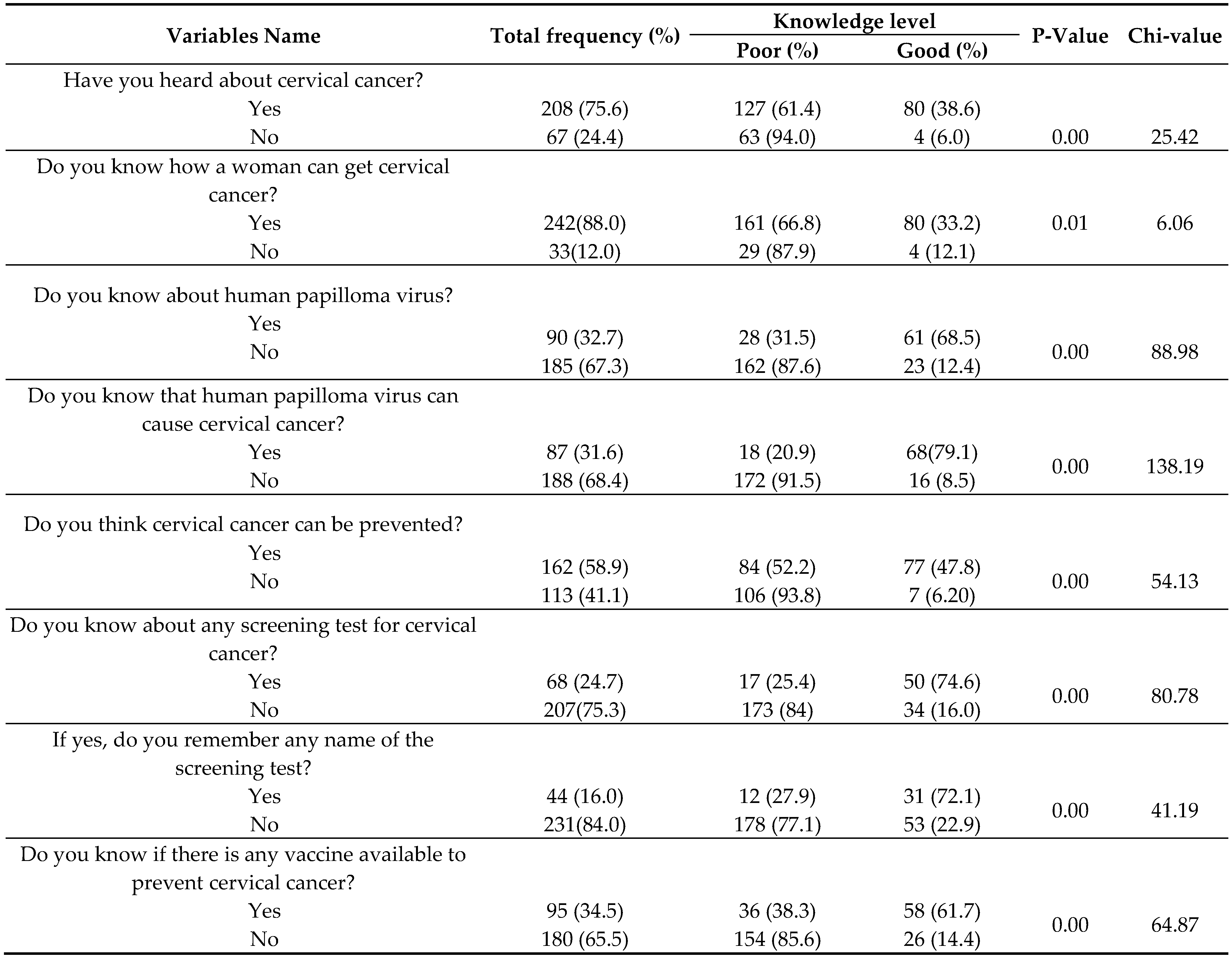

Table 5 showed the association between knowledge level and knowledge related variables among the study participants. The knowledge level was categorized into poor and good levels. When did they ask the question have you heard about cervical cancer? Among the participants, almost three fourth (75.6%) said yes which illustrates that 38.6% of them have good knowledge regarding cervical cancer and the remaining 61.4% have poor knowledge associated with cervical cancer due to the lack of knowledge and awareness. On the other hand, around one-fourth (24.4 %) of participants replied no that majority (94%) has poor knowledge. Moreover, only 12% of the respondents don’t know how a woman can get cervical cancer while only 12.1% have good knowledge, and more than two third (66.8%) have poor knowledge among the highest number of participants (88%) of them know how to get cervical cancer and P-value is significant (p<0.05). It illustrates that the knowledge level of respondents is significantly associated with the level of knowledge regarding cervical cancer prevention (p < 0.05). Almost 32.7 % of participants know about human papillomavirus while 31. 6% have knowledge that human papillomavirus can cause cervical cancer among them more than three fourth (79.1%) have good knowledge.

Furthermore, more than half (58.9%) of the participants think cervical cancer can be prevented among them 47.8% level good and 52.2% have poor knowledge. Among all participants fourth (24.7%) know about any screening test for cervical cancer and only 16% could remember the name of the screening test. In addition to 34.5% know about the vaccine available to prevent cervical cancer and 61.7% have good knowledge about it.

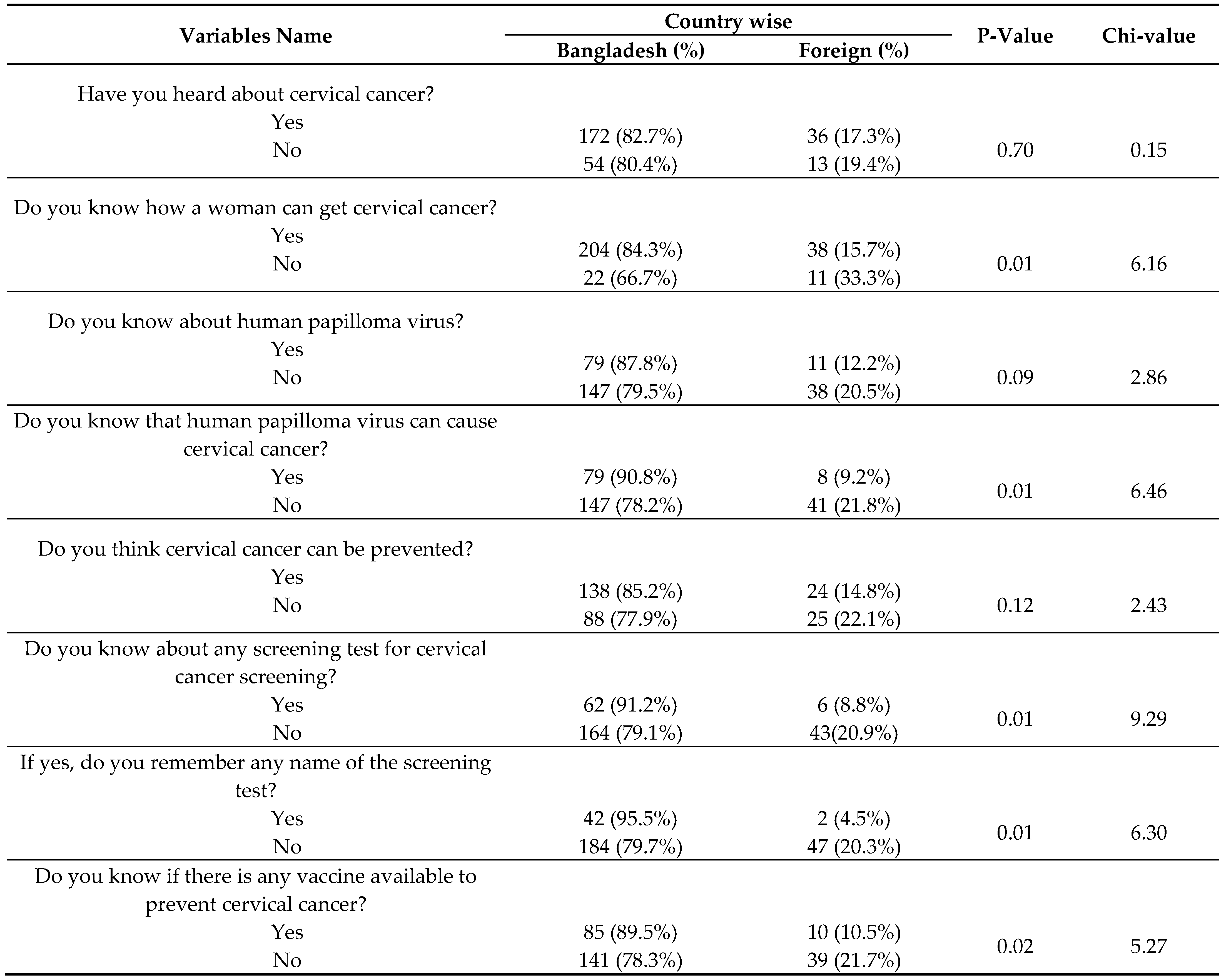

We also analyzed the association between the country of students and their response to knowledge-related questions (See

Table 6). Among the total participants 82.7% Bangladeshi and 17.3% foreign students were heard about cervical cancer previously. Of total, 84.3% of Bangladeshi participants had knowledge about how women get cervical cancer while of foreign participants was 15.7 % with P-value 0.01. The study found that 78.2% of Bangladeshi and 21.8% of foreign respondents don’t know about the causal agent of cervical cancer and the difference was significant.

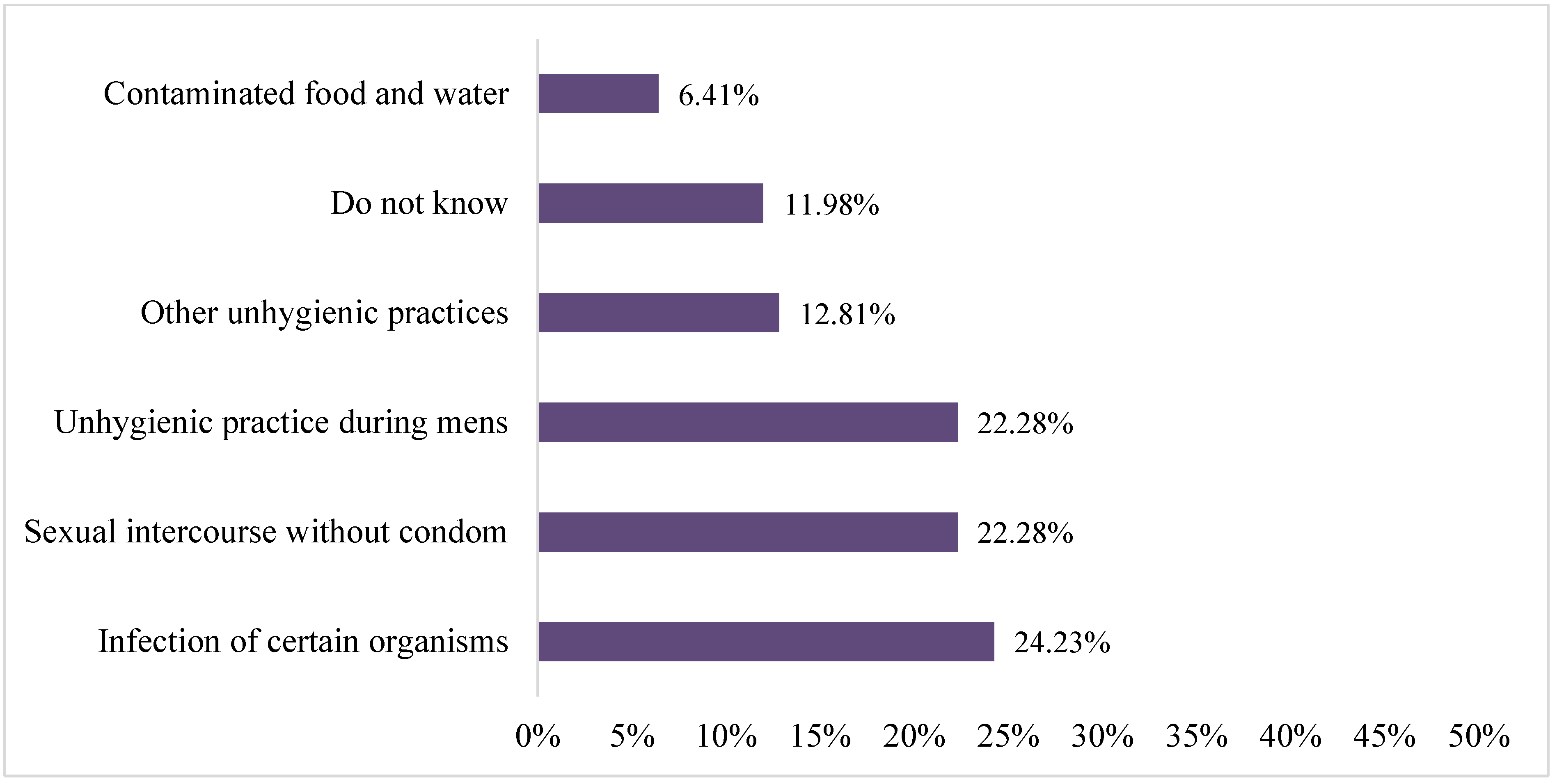

Knowledge about cause and prevention of cervical cancer

Figure 1 depicts the knowledge of students regarding the causes of cervical cancer. Higher proportion of responses were the infection of organism (24.23%), unsafe sexual intercourse (22.28%), and poor reproductive hygiene (22.28%). A part of them (6.41%) also knew about the role of food and water for causing cancer. However, 11.98% had no idea about the factors causing cervical cancer.

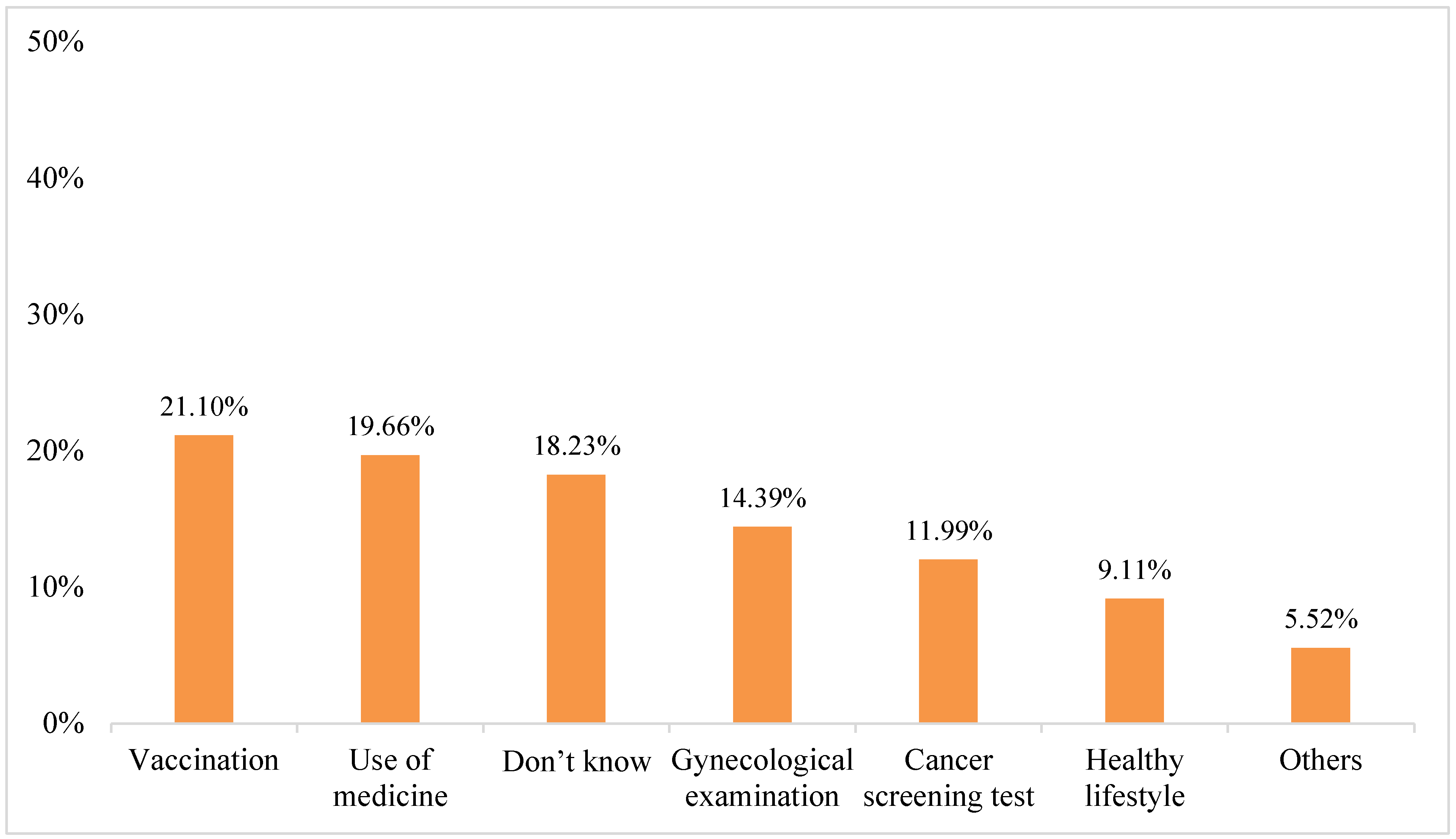

Students under this study mentioned different precautions for preventing cervical cancer (See

Figure 2). Of total 21.1% identified vaccination and 11.99% marked screening test. Gynecological examination (14.39%) and healthy lifestyle (9.11%) also identified by significant number of students.

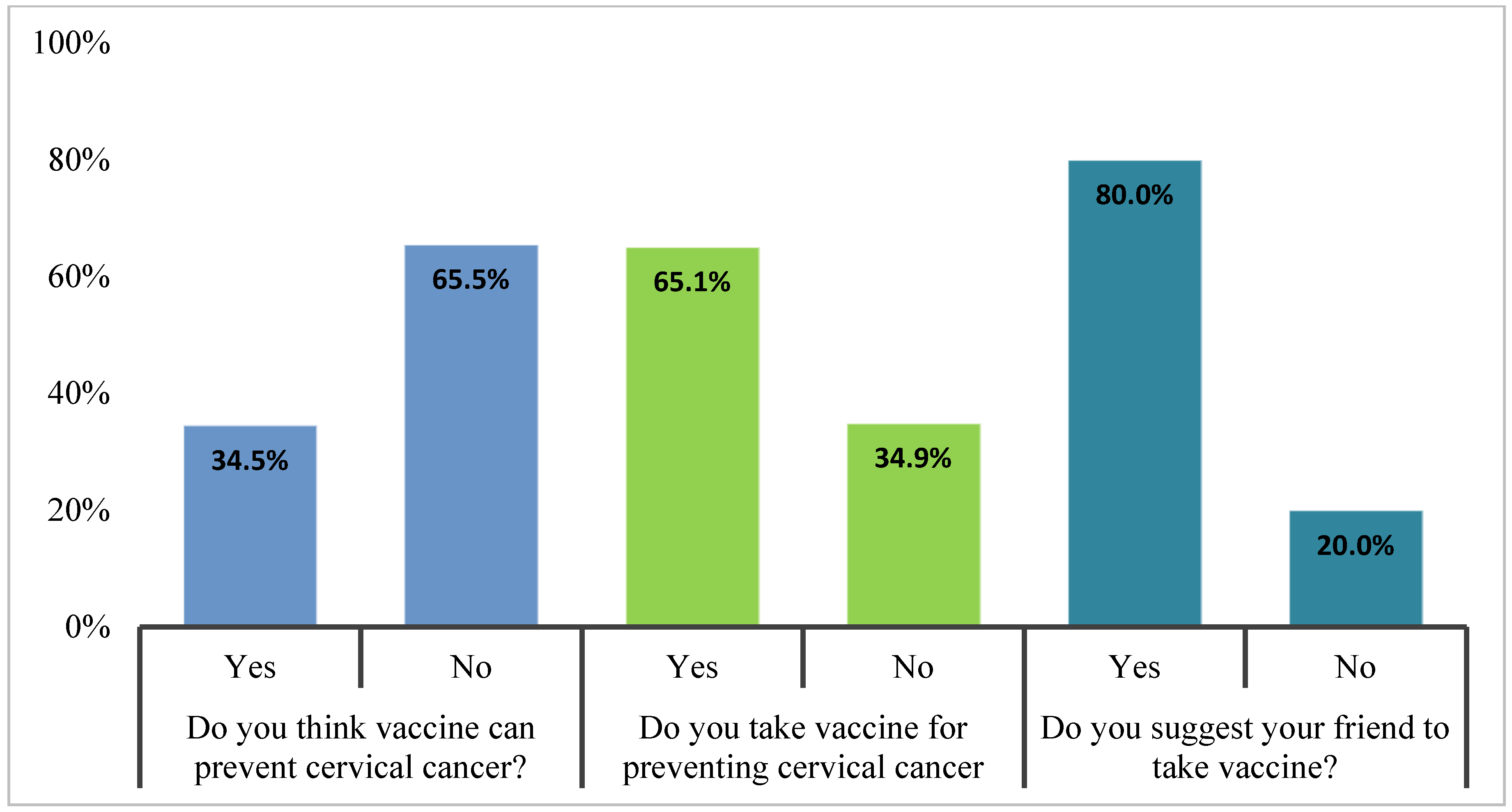

Perception about cervical cancer vaccination

Figure 3 demonstrates the perceptions of students regarding the vaccination for cervical cancer. Although 65.5% of students did not think that vaccines can prevent this cancer, most of them was agreed to take the vaccine (65.1%) and also recommend it to others (80%). However, a significant proportion of students (34.9%) were not willing to take vaccine.

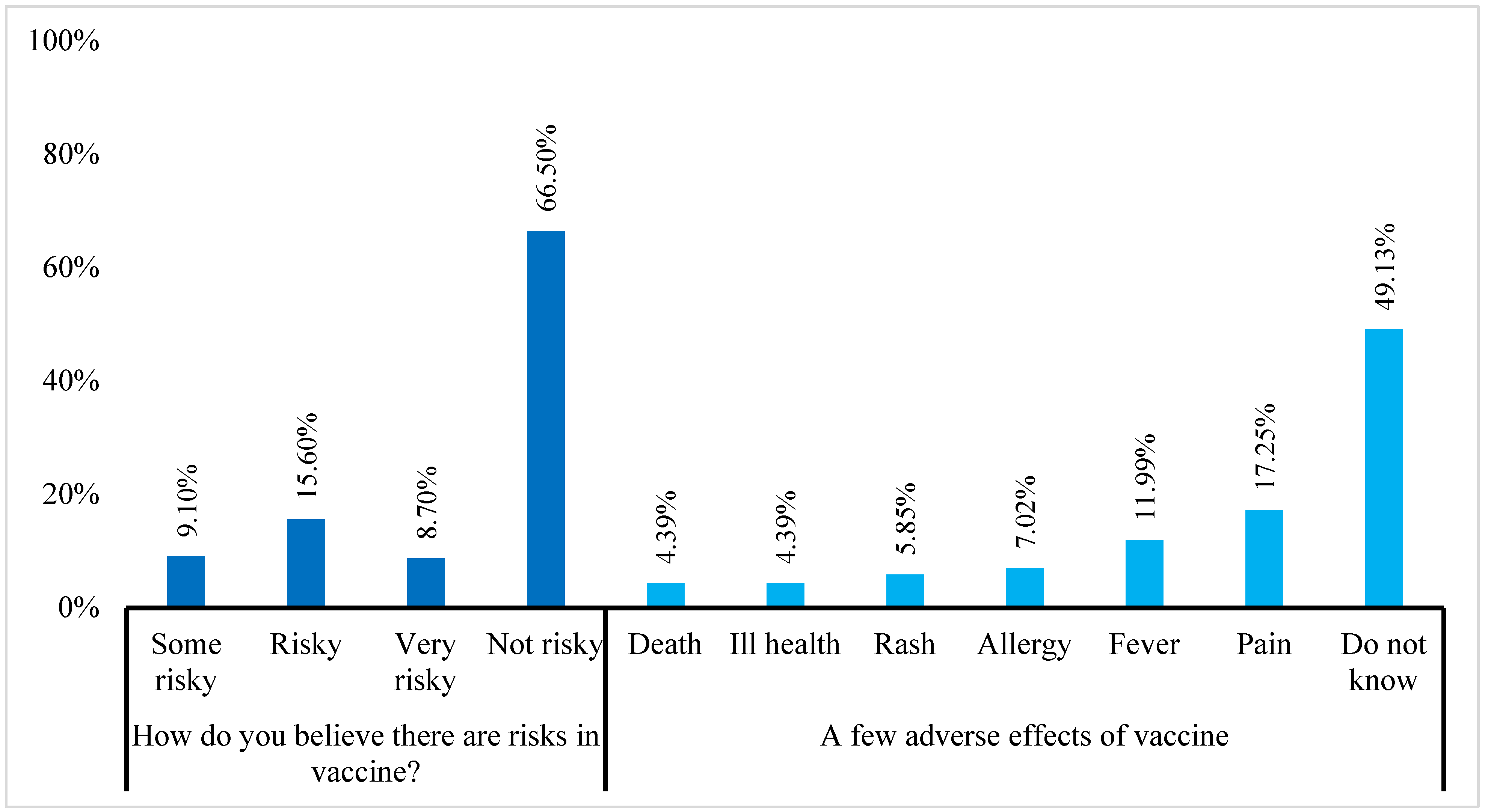

Figure 4 represents the belief of students about the side effects of vaccine. One third of students (33.4%) acknowledged different extent of risks associated with the vaccine. They expressed pain (17.25%), fever (11.99%) and allergy (7.02%) as the most frequent adverse effects. Surprisingly, 4.39% students marked death due to vaccination.

4. Discussion

We investigated the knowledge of different aspects of cervical cancer among 275 female students in Chattogram city of Bangladesh. Results show that most of the students had no idea about the risk factors and prevention methods of cervical cancer and the overall knowledge was poorly noticeable which was supported by previous studies in Bangladesh, India, Sri- Lanka, Nepal, and Ethiopia (6,18–20). The respondents heard about cervical cancer which was similar to a previous study conducted among middle-aged women in Bangladesh and other countries (6,21–23). Student’s country of origin has a significant association with knowledge of CC. It showed that Bangladeshi female students have more knowledge than foreign students. The marital status has variation among the participants which estimated that unmarried students had better knowledge compared with married participants. This was similar to another study which had conducted among the women in Tangail district Bangladesh (6). In the contrast, most of the females in this study did not able to recognize the high risk of CC due to a lack of knowledge and awareness.

The findings of this study showed that almost half of the respondents heard about CC from newspapers/television and from doctors along with other sources such as social media, friends, and relatives which was similar to the findings of other studies conducted in Nigeria, India, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Pakistan (22–24). Our findings were also comparable with another study conducted at Wollega University which found the role of mass media such as television and radio (36%), brochures and posters (12.4%), and health workers (7.3%) (18,25). This study's findings indicate that mass media and doctors play an important role to create awareness among the community people regarding CC and it can curable if it’s diagnosed at a very early stage. In this finding, more than half of the respondents had no idea that human papillomavirus can cause cervical cancer which was similar to previous studies conducted in Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Nigeria, and Ethiopia (19,20,22,23).

We assessed the knowledge and attitude of the respondents toward cervical cancer and its treatment and screening facility. Although more than half of the students stated that they think CC can be preventable a significant number of them were unaware of any screening test in Bangladesh. The finding was comparable with another study which found that 8.7% of women knew about a Pap smear is a screening test for cervical cancer (6). Similar findings were reported in Pakistan and India that CC could be detected by Pap smear (23,25). Moreover, the majority of participants do not know about the vaccines available in Bangladesh for the prevention of CC which evident the lack of knowledge regarding vaccination in Bangladesh. This could be the reason of diagnosis of cervical cancer at an advanced stage in Bangladesh. Among all the participants higher percentage of the respondent do not think vaccines can prevent cancer and also, they do not take vaccines for preventing cervical cancer. This creates the need of special attention to the prevention of the disease through early vaccination and increase awareness regarding this serious health issue.

We conducted this study in a single institution which was the limitation of the study. Our participants were the female students and therefore the results reflect the status of women of reproductive age who are at high risk of cervical cancer which is a big strength of this survey. Further extended survey including students of various disciplines from rural and urban areas of different parts of the country is highly recommended.

5. Conclusion

In sum, the overall knowledge of students was poor about cervical cancer, its causes and prevention. The study found most of the students had poor confidence on the effectiveness of cervical cancer vaccine for the prevention this cancer, however, they agreed to take the vaccine which reflects their positive attitude towards the prevention of their health problems. Therefore, providing the right information through proper channels could raise awareness among the mass people especially women of reproductive age.

References

- Šarenac T, Mikov M. Cervical Cancer, Different Treatments and Importance of Bile Acids as Therapeutic Agents in This Disease. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Dec 31];10(JUN). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6558109/.

- WHO. Cervical cancer [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cervical-cancer#tab=tab_1.

- Mengesha A, Messele A, Beletew B. Knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer among reproductive age group women in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Feb 11 [cited 2022 Dec 31];20(1):1–10. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-8229-4.

- WHO. A cervical cancer-free future: First-ever global commitment to eliminate a cancer [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-11-2020-a-cervical-cancer-free-future-first-ever-global-commitment-to-eliminate-a-cancer.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2021 May [cited 2022 Dec 31];71(3):209–49. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33538338/.

- Alam NE, Islam MdS, Rayyan F, Ifa HN, Khabir MIU, Chowdhury K, et al. Lack of knowledge is the leading key for the growing cervical cancer incidents in Bangladesh: A population based, cross-sectional study. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan 4 [cited 2022 Dec 31];2(1):e0000149. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0000149.

- WHO. Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control A guide to essential practice Second edition. 2006.

- Underwood SM, Ramsay-Johnson E, Dean A, Russ J, Ivalis R. Expanding the Scope of Nursing Research in Low Resource and Middle Resource Countries, Regions, and States Focused on Cervical Cancer Prevention, Early Detection, and Control. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc [Internet]. 2009 Dec [cited 2022 Dec 31];20(2):42. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3170715/.

- Hoque MR, Haque E, Karim MR. Cervical cancer in low-income countries: A Bangladeshi perspective. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];152(1):19–25. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijgo.13400.

- ARHP. Managing PV: A New Era in Patient Care. Association of Reproductive Health Professionals [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2022 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.guidestar.org/profile/52-1591381.

- Franceschi S, Herrero R, Clifford GM, Snijders PJF, Arslan A, Anh PTH, et al. Variations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women worldwide. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2006 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];119(11):2677–84. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijc.22241.

- Tobian AAR, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, Laeyendecker O, et al. Male Circumcision for the Prevention of HSV-2 and HPV Infections and Syphilis. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2009 Mar 26 [cited 2022 Dec 31];360(13):1298–309. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa0802556.

- Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];8(2):e191. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7025157/.

- Montgomery K, Bloch JR, Bhattacharya A, Montgomery O. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Knowledge, Health Beliefs, and Preventative Practices in Older Women. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing [Internet]. 2010 May 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];39(3):238–49. Available from: http://www.jognn.org/article/S0884217515302859/fulltext.

- WHO. National Strategy for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control in Bangladesh, 2017-2022 [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/bangladesh/news/detail/24-09-2017-national-strategy-for-cervical-cancer-prevention-and-control-in-bangladesh-2017-2022.

- Rakhshanda S, Dalal K, Chowdhury HA, Mayaboti CA, Paromita P, Rahman AKMF, et al. Assessing service availability and readiness to manage cervical cancer in Bangladesh. BMC Cancer [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];21(1):1–10. Available from: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-021-08387-2.

- HPV information center. Human Papillomavirus and related diseases report, Bangladesh [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Dec 31]. Available from: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/BGD.pdf.

- Mustari S, Hossain B, Diah NM, Kar S. Opinions of the Urban Women on Pap Test: Evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];20(6):1613. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7021619/.

- Cermak M, Cottrell R, Murnan J. Women’s knowledge of HPV and their perceptions of physician educational efforts regarding HPV and cervical cancer. J Community Health [Internet]. 2010 Jun 5 [cited 2022 Dec 31];35(3):229–34. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-010-9232-y.

- Sankaranarayanan R, Bhatla N, Gravitt PE, Basu P, Esmy PO, Ashrafunnessa KS, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer prevention in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. Vaccine [Internet]. 2008 Aug 19 [cited 2022 Dec 31];26 Suppl 12(SUPPL. 12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18945413/.

- Kadian L, Gulshan G, Sharma S, Kumari I, Yadav C, Nanda S, et al. A Study on Knowledge and Awareness of Cervical Cancer Among Females of Rural and Urban Areas of Haryana, North India. Journal of Cancer Education [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];36(4):844–9. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13187-020-01712-6.

- Isara A, Awunor N, Erameh L, Enuanwa E, Enofe I. Knowledge and practice of cervical cancer screening among female medical students of the University of Benin, Benin City Nigeria. Annals of Biomedical Sciences [Internet]. 2013 Apr 21 [cited 2022 Dec 31];12(1). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/abs/article/view/87616.

- Riaz L, Manazir S, Jawed F, Arshad Ali S, Riaz R. Knowledge, Perception, and Prevention Practices Related to Human Papillomavirus-based Cervical Cancer and Its Socioeconomic Correlates Among Women in Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus [Internet]. 2020 Mar 5 [cited 2022 Dec 31];12(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32269867/.

- Tilahun T, Tulu T, Dechasa W. Knowledge, attitude and practice of cervical cancer screening and associated factors amongst female students at Wollega University, western Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes [Internet]. 2019 Aug 19 [cited 2022 Dec 31];12(1):1–5. Available from: https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13104-019-4564-x.

- Patra S, Upadhyay M, Chhabra P. Awareness of cervical cancer and willingness to participate in screening program: Public health policy implications. J Cancer Res Ther [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1 [cited 2022 Dec 31];13(2):318–23. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28643754/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).