1. Introduction

Dental education is an intricate and arduous process that involves taxing pedagogical experience with unique challenges [1]. The ultimate goal of undergraduate dental education is to equip the future dentists with underpinning scientific knowledge, clinical skills and affective skills for safe practice of Dentistry [2]. In addition to clinical operative procedures, dental graduates are expected to exhibit competence in the soft skills that include time management, critical thinking, problem solving, professionalism, leadership, team working and interprofessional collaborative practice [3]. The aim of undergraduate dental education is to produce scientifically proficient and socio-empathic dental practitioners who strive to observe premier standards of ethics and professionalism to serve the society [4,5].

An array of factors influences the quality of undergraduate dental programmes including curricular design; clinical training model; effective alignment of programme learning outcomes with teaching and assessment methods. The conducive learning environment has pivotal role in ensuring effective students' learning [6]. Likewise, teachers are the backbone of an education system and the provision of quality supervision, support and timely feedback by competent clinical teachers can enhance the students’ experiential learning [7,8]. Previous research on dental students has identified several areas of weaknesses amongst new dental graduates suggesting dental programmes may not always be able to train the dental students to the expected standards [9-11]. The transition from undergraduate dental student to the actual dental practice is a crucial but challenging step [12]. Evidence from the literature shows that although most of the dental students are adequately equipped to carry out simple operative procedures, they may not be prepared to carry out more complex clinical procedures.4 Considering this, ensuring the preparedness of graduates for the complexity and demands of contemporary dental practice is a daunting task [13]. The dynamic healthcare environment of the modern-day society necessitates to adequately prepare the healthcare professions students, hence, enabling them to follow the evidence-based approaches for the prevention, diagnosis and management of oral diseases [4,13].

The dental faculty evaluates students' work preparedness through continuous formal and informal assessments. Nevertheless, it is important to develop an understanding of the work preparedness as perceived by students themselves [6]. Self-reported preparedness may be an important benchmark to identify the shortcomings in training and to rectify them by encompassing change in curriculum design. Moreover, evaluation of students’ self-perceived preparedness may encourage them to practice reflection through self-assessment that can facilitate development of lifelong learning skills [8].

Several studies have explored the self-perceived readiness of the undergraduate dental students in United Kingdom, United States of America, Europe, Hongkong and Malaysia [4,6,12,14,15,16]. Likewise, the studies have been conducted in Pakistan [3,17]. However, previous studies in Pakistan were conducted on a limited sample. The number of dental colleges in Pakistan has increased exponentially since 1990 to meet the increasing healthcare needs of the population [18]. Annually, approximately, 3700 dentists graduate from 18 public sector (1200 students) and 43 private sector dental colleges (2500 students) in Pakistan [19].

The aim of the current national study was to evaluate the self-perceived preparedness of undergraduate dental students and new graduates working as house officers in the dental institutions of Pakistan.

2. Materials and Methods

A prospective cross-sectional National study was conducted at dental schools of Pakistan. Purposive sampling technique was used to recruit house officers and undergraduate dental students (Pre-final year and Final year) at 27 public and private dental schools in Pakistan by using an e-questionnaire. The total population of the students (Pre-final year and Final year) and house officers in 27 institutes was 5112. The acceptable number of responses were calculated as 588 by setting the confidence level at 99% and margin of error at 5%. Raosoft sample size calculator was used (

http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html). Ethics approval was obtained from institutional review committee (IRC) at Riphah International University, Pakistan (IIDC/IRC/2021/002/006).

The study employed Dental Undergraduates Preparedness Assessment Scale (DU-PAS). DU-PAS is a reliable and validated instrument for measuring a wide range of attributes, competencies and skills expected from dental graduates [20]. The scale has two sections. Section A of scale comprises of 24 items that assess the graduates’ competency in the clinical skills. Section B comprises of 26 items focusing on the soft skills including professionalism, cognitive ability and communication skills. Both sections are scored by using a three-point scale as follow. Section A: (0) No experience, and (1) with colleague’s practical or/and verbal input, (2) Independently. Section B: (0) No experience, (1) Mostly, and (2) Always. The cumulative score range for DU-PAS is between 0 and 100.

The e-questionnaire (google form link) and participation information sheet were administered at the culmination of academic year. The administration was done through the focal person at each of the 27 dental schools (7 Public and 20 Private) in the WhatsApp groups of third/final year students and house officers. Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants and the potential participants were informed that submission of the response will be considered as their consent to participate in the study. Subsequently, four reminders were given at an interval of four weeks. Data collection process was concluded in five months.

The data analysis was carried out using the R statistical environment for Windows (R Core Team, 2015). Data collection and analysis were completed in six months.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The total sample consists of 862 responses from across 642 (74.59%) Females and 219 (25.41%) Males, with a mean age of 23.42 years (SD=1.28, Range=20-30). Whilst mean ages were comparable between genders, the distributions varied significantly between Female (Mean=23.32, SD=1.26, Range=20-30) and Male (Mean=23.69, SD=1.31, Range=20-29) respondents (χ (10, n=855) =19.874, p=0.030) – this is depicted in

Figure 1.

Of the 862 responses, 581 (67.40%) were received from Private Institutions, and 281 (32.60%) from Public Institutions. In addition, the proportion of Female respondents at private institutions was higher at Private institutions (Female, 22.72% Male) compared to Public institutions (77.28% vs 69.04%; χ(1n=862)=6.36, p=0.012). However, the distribution of Age within Private and Public Institutions did not differ significantly (χ(10,n=855)=15.09, p=0.129). The sample included 507 (58.83%) final-year BDS students (359 Female, 148 Male), 36 (4.18%) pre-final-year BDS students (25 Female, 11 Male), and 319 (37.01%) House Officers (259 Female, 60 Male). Majority of the respondents were from Punjab (n=483, 56.03%), followed by Federal Capital Territory (n=168, 19.49%), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (n=142, 16.47%), Sindh (n=53, 6.15%), and Baluchistan (n=16, 1.86%).

3.2. Overall Scores

Overall scores by Part are shown in

Table 1. These are calculated based on converting responses in Part A (24 Items) and B (26 Items) to numeric scores as; Independently = 2, With Help = 1, and No Experience = 0 (Part A) and Always = 2, Mostly = 1, and No Experience = 0 (Part B).

3.2.1. Part A Items

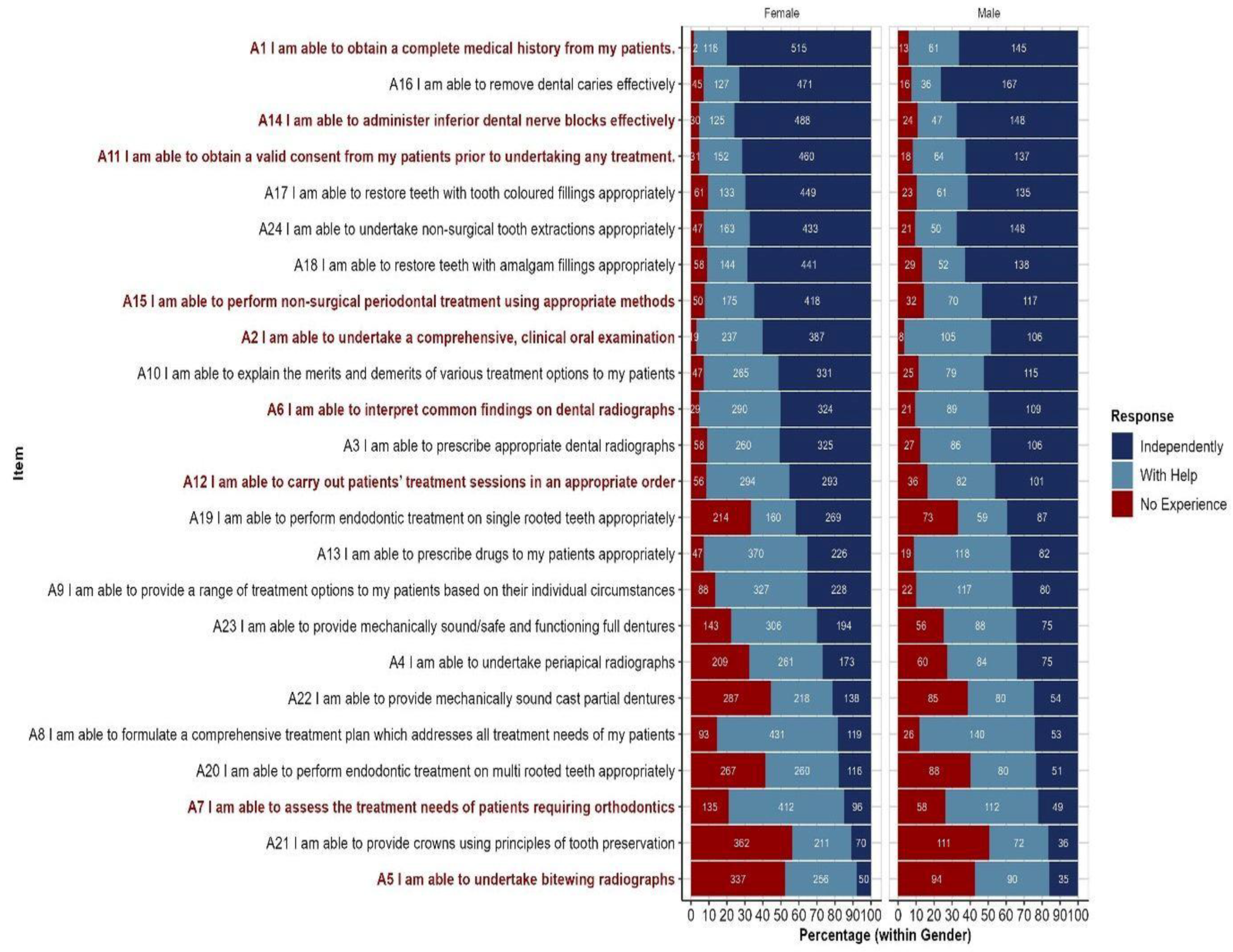

The responses to each item, by gender, are shown in

Figure 2. This figure is ordered from highest to lowest proportion of ‘independently’ responses, and highlights items for which the response profile differs significantly by gender at the p<0.05 level. These items are also listed in

Table 2 along with related p-values.

The responses to each item, by Institution Type, are shown in

Figure 3. This figure is ordered from highest to lowest proportion of responses reported as “independently”, and highlights items for which the response profile differs significantly between Private and Public Institutions (p<0.05). These items are also listed in

Table 3 along with the related p-values.

3.2.2. Part B Items

The responses to each item, by gender, are shown in

Figure 4. This figure is ordered from highest to lowest proportion of ‘Always’ responses, and highlights items for which the response profile differs significantly by gender at the p<0.05 level. These items are also listed in

Table 4, along with related p-values.

The responses to each item, by Institution Category, are shown in

Figure 5. This figure is ordered from highest to lowest proportion of ‘Always’ responses, and highlights items for which the response profile differs significantly between Private and Public/Government Institutions at the p<0.05 level. These items are also listed in

Table 5, along with related p-values.

4. Discussion

This is the first national study reporting self-perceived preparedness dental students and new graduates from multiple private and public sector dental institutions in Pakistan. The study provides useful insights into the preparedness of dental students and graduates from Pakistan and highlights several areas of weakness which warrant attention and remedial measures by dental educators in Pakistan.

Based on the total mean score of the study respondents, dental undergraduates of Pakistan reported to be less prepared (mean score 61.10) compared to dental students from other countries like Malaysia (79.5%) and the United Kingdom (74%) [4,14].

In the present study, respondents felt most prepared to record medical history, remove dental caries and administer inferior dental nerve blocks. Similar findings were reported by other studies investigating students from not only Pakistan but also the United Kingdom [3,14,17]. Considering these are generally straightforward, it is not surprising to find this similarity among students of developing and developed countries.

Regarding areas of deficiency in clinical skills, experience in performing endodontics was observed to be deficient and respondents from both private as well as public sector institutions reported a lack of experience in performing endodontic treatment on multi rooted teeth (61.1%) and also single rooted teeth (33.3%). In contrast, Ali et al., reported only that only 2.4% of dental students in the UK did not have any experience of carrying out endodontic treatment on single rooted teeth [14]. Moreover, with respect to the endodontic treatment of multi rooted teeth, a significant difference was observed in the preparedness of respondents from private sector compared with those from public sector. These differences are quite remarkable and highlight the need for further clinical experience in endodontics for dental students in Pakistan [21]. Interestingly, developed countries face a similar challenge in undergraduate endodontic education [22,23].

Radiography skills were also flagged up as a relatively weak area in the present study. Respondents of the present study were least prepared to taking bitewing radiographs in contrast to participants from the UK and Malaysia [4,14]. Qazi et al reported a similar lack of confidence in performing bitewings among Pakistani students in contrast to students from Malaysia and United Kingdom [4,14,17]. Anecdotal evidence suggests that dental students in Pakistan do not get adequate experience in bitewing radiography. Instead, there is a preference for using periapical radiographs to diagnose dental caries which is inappropriate. These findings underscore the need to revisit radiology teaching and align it with contemporary and evidence-based clinical practice.

Other areas of reported weakness include assessment of orthodontic treatment needs; provision of crowns and, fabrication of cast partial dentures. These findings concord with those reported by with Qazi et al, Ali et al and Mat Yudin et al, who reported similar challenges for students in Pakistan, United Kingdom and Malaysia respectively [4,14,17]. More importantly, however, there was a significantly high proportion of participants in this study who reported “no experience” in these skills. Given these are core skills expected from a general dental practitioner, these findings raise serious concerns regarding the breadth of clinical training in Pakistani dental institutions. The present study has managed to capture the magnitude of these deficiencies in clinical skills which was not achieved in a previous study on a relatively smaller study sample.

Majority of the respondents felt prepared to communicate with the patients, seek help from supervisors, protect patient confidentiality among other attributes of professionalism. These observations are positive and demonstrate a professional and ethical culture in educational and clinical settings. However, the participants felt less prepared regarding interpretation of research to inform their clinical practice, evaluation of dental materials/ products using an evidence-based approach and, the referral of patients suspected of oral cancer. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies on preparedness of dental students and new graduates [3,14,17]. Understanding and application of evidence-based dentistry in undergraduate dental education remains a challenge globally despite the growing emphasis on its importance in the last two decades [24]. In the absence of a structured course on evidence-based dentistry in undergraduate dental curricula in Pakistan, the findings are not unexpected. Dental institutions in Pakistan need to develop a comprehensive strategy to incorporate principles of evidence-based dentistry in undergraduate curricula [25,26]. It may be helpful to learn from experiences of dental institutions in the West who provide teaching on evidence-based practice to make informed decisions on updating existing dental curricula in Pakistan [27,28].

Given that Pakistan has one of the highest global incidences of oral cancer, it is ironic that Pakistani dental students and graduate feel unprepared to recognize and refer suspected oral cancer. This may be related to lack of consistencies in the teaching and clinical exposure to patients with oral cancer. Early detection and prompt management of oral cancer is most critical in improving cancer survival rates and reducing cancer-related morbidity and mortality [29]. Unfortunately, a similar lack of preparedness was identified in other countries like the United Kingdom and Malaysia [4,14]. Structured exposure to oral cancer patients in specialist oral and maxillofacial surgery settings is essential to improve students’ confidence in recognition and referral of oral cancer.

The data also highlighted several gender-related differences in self-reported preparedness. Female students felt better prepared in history taking, clinical examination, radiographic interpretation, treatment sequencing and non-surgical periodontal treatment. On the other hand, male respondents reported better prepared to assess orthodontic treatment needs, and bitewing radiography. Other notable differences related to affective skills as female respondents felt more prepared to maintain professional relationship with patients, effectively communicate with patient and reflect on their clinical practice. A similar gender-related disparity is observed in other studies, with the female students reported to demonstrate better empathy towards patients compared to male students [30]. In contrast the male respondents felt more prepared to interpret research for clinical application and evaluate materials using an evidence-based approach. However, contrary to the evidence indicating a lack of confidence among female undergraduate dental students, findings of our study show female students as more prepared than male students in terms of clinical skills and professionalism [12,30]. These differences may be attributed to a higher proportion of females in the study sample and perhaps also to growing female empowerment in the society [31,32].

Finally, differences were also noted between participants from private and public sector institutions. Participants from private institutions felt better prepared in attributes related to professionalism which may reflect cultural differences in private and public sector institutions. Also, Public sector institutions face a much higher inflow of patients. Increased workload and time constraints may impact adversely on novice clinicians’ interpersonal skills, although this cannot be justified and needs remedial action.

The preparedness for practice is a complex concept, which can be studied through the perspective of academicians, students, dentists, and patients [33,34]. In this study, preparedness of a large sample was measured from a student’s perspective using a validated tool which contributes to an improved internal and external validity. However, caution may be exercised while interpreting self-reported preparedness by dental students as the scores may be inflated by “unconscious incompetence” or a lack of experience in self-evaluation [35,36]. Evidence regarding correlation between actual clinical competence and perceived self-confidence is weak [37]. Nevertheless, the overall mean scores of participants in this study appear to be lower than those reported in previous studies from the UK, Malaysia, and Pakistan which also used the DU-PAS instrument. These differences may underscore “conscious incompetence” amongst the participants in this study or a genuine lack of preparedness. Another factor which may have contributed to the lower mean scores of the study participants might be related to inclusion of Pre-final year students who had less experience. It is also worth-emphasizing that the study was conducted following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is possible that the lower level of preparedness reported by the study participants may reflect the adverse impact of the pandemic on their teaching and training [38,39,40]. Dental institutions must ensure that appropriate checks are in place to monitor the quality of their graduates and support is available for new graduates to address any gaps in clinical experience. The implementation of reflective learning with feedback in undergraduate Pakistani curriculum can be a step towards improving the self-perceived preparedness of clinical skill [41].

5. Conclusions

This study investigated self-reported preparedness of a large sample of Pakistani undergraduate dental students and new graduates using a validated instrument. The results highlight the strengths and weaknesses of dental students and new graduates in Pakistani dental institutions. The findings may be used to further develop and strengthen teaching and training of dental students in Pakistan. The findings may be of interest to dental educators in Pakistan and further afield. DU-PAS appears to be a reliable instrument to quantify preparedness of dental graduates from different parts of the world. In future mixed methods research involving qualitative methods may be employed to engage with a range of stakeholders in dental education. Such an approach may help gain a deeper understanding of the factors which influence the preparedness of dental students and the role dental institutions can play to improve the learning experiences of the students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Q.J., and S.N.; Methodology, M.Q.J., A.M.A., and K.A., Investigation, M.Q.J., S.N., S.A., and U.A.B., formal analysis, D.Z., data curation M.Q.J., and M.H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Q.J, S.N., U.A.B., D.Z., and K.A.; writing—review and editing, M.Q.J., S.A., M.H.A., A.M.A., and K.A.; supervision, M.Q.J. and K.A.; project administration, M.Q.J., and .; funding acquisition, M.Q.J., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University for funding the publication of this project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local committee for bioethics, institutional review committee (IRC) at Riphah International University, Pakistan (IIDC/IRC/2021/002/006).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants and the potential participants were informed that submission of the response will be considered as their consent to participate in the study

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University for funding the publication of this project. Also. we are thankful to all the focal persons at participating institutions who facilitated data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arora G, Nawabi S, Uppal M, Javed MQ, Yakub SS, Shah MU. Dundee ready education environment measure of dentistry: Analysis of dental students' perception about educational environment in college of dentistry, Mustaqbal University. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 2021 Nov;13(Suppl 2):S1544. [CrossRef]

- Cowpe J, Plasschaert A, Harzer W, Vinkka-Puhakka H, Walmsley AD. Profile and competences for the graduating European dentist– update 2009. Eur J Dent Educ 2010: 14: 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Ali K, Cockerill J, Zahra D, Qazi HS, Raja U, Ataullah K. Self-perceived preparedness of final year dental students in a developing country—A multi-institution study. European Journal of Dental Education. 2018 Nov;22(4):e745-50. [CrossRef]

- Mat Yudin Z, Ali K, Wan Ahmad WM, Ahmad A, Khamis MF, Brian Graville Monteiro NA, Che Ab. Aziz ZA, Saub R, Rosli TI, Alias A, Abdul Hamid NF. Self-perceived preparedness of undergraduate dental students in dental public universities in Malaysia: A national study. European Journal of Dental Education. 2020 Feb;24(1):163-8. [CrossRef]

- Manakil J, George R. Self-perceived work preparedness of the graduating dental students. European Journal of Dental Education. 2013 May;17(2):101-5. [CrossRef]

- Javed MQ. The evaluation of empathy level of undergraduate dental students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad. 2019 Jul 10;31(3):402-6.

- Nawabi S, Shaikh SS, Javed MQ, Riaz A. Faculty’s Perception of Their Role as a Medical Teacher at Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2020 Jul;12(7). [CrossRef]

- Javed MQ, Ahmed A, Habib SR. Undergraduate Dental Students’and Instructors’perceptions about the Quality of Clinical Feedback. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2021;33(1).

- Rodd HD, Farman M, Albadri S, Mackie IC. Undergraduate experience and self-assessed confidence in paediatric dentistry: comparison of three UK dental schools. Br Dent J. 2010;208(5):221-225. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Duncan HF. Radiographic evaluation of the technical quality of undergraduate endodontic ‘competence’ cases in the Dublin Dental University Hospital: an audit. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2012;58(3):162-166.

- Durham JA, Moore UJ, Corbett IP, Thomson PJ. Assessing competency in dentoalveolar surgery: a 3-year study of cumulative experience in the undergraduate curriculum. Eur J Dent Educ. 2007;11(4):200-207. [CrossRef]

- Gilmour AS, Welply A, Cowpe JG, Bullock AD, Jones RJ. The undergraduate preparation of dentists: Confidence levels of final year dental students at the School of Dentistry in Cardiff. British dental journal. 2016 Sep;221(6):349-54. [CrossRef]

- Monrouxe LV, Bullock A, Gormley G, Kaufhold K, Kelly N, Roberts CE, Mattick K, Rees C. New graduate doctors’ preparedness for practice: a multistakeholder, multicentre narrative study. BMJ open. 2018 Aug 1;8(8):e023146. [CrossRef]

- Ali K, Slade A, Kay E, Zahra D, Tredwin C. Preparedness of undergraduate dental students in the United Kingdom: a national study. Br Dent J. 2017;222(6):472-477. [CrossRef]

- Hook CR, Comer RW, Trombly RM, Guinn JW 3rd, Shrout MK. Treatment planning processes in dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(1):68-74. [CrossRef]

- Yiu CK, McGrath C, Bridges S, Corbet EF, Botelho MG, Dyson JE, Chan LK. Self-perceived preparedness for dental practice amongst graduates of The University of Hong Kong’s integrated PBL dental curriculum. European Journal of Dental Education. 2012 Feb;16(1):e96-105. [CrossRef]

- Qazi HS, Ali K, Cockerill J, et al., Self-perceived competence of new dental graduates in Pakistan – A multi-institution study. PAFMJ, 2021. 71(3), 739-43. [CrossRef]

- Khan AW, Sethi A, Wajid G, Yasmeen R. Challenges towards quality assurance of Basic Medical Education in Pakistan. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2020 Jan;36(2):4. [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Medical Commission. List of Recognized Pakistan Dental Colleges. 2022. cited 2022 Jan 30. Available from: https://www.pmc.gov.pk/colleges.

- Ali K, Slade A, Kay EJ, Zahra D, Chatterjee A, Tredwin C. Application of Rasch analysis in the development and psychometric evaluation of dental undergraduates preparedness assessment scale. Eur J Dent Educ. 2017 Nov;21(4):e135-e141. [CrossRef]

- Bhatti UA, Qureshi B, Azam S. Trends in contemporary endodontic practice of Pakistan: a national survey. J Pak Dent Assoc 2018;27(2):50-56. [CrossRef]

- Davey J, Bryant ST, Dummer PM. The confidence of undergraduate dental students when performing root canal treatment and their perception of the quality of endodontic education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015 Nov;19(4):229-34. [CrossRef]

- Haug SR, Linde BR, Christensen HQ, Vilhjalmsson VH, Bårdsen A. An investigation into security, self-confidence and gender differences related to undergraduate education in Endodontics. Int Endod J. 2021 May;54(5):802-811. [CrossRef]

- Bala MM, Poklepović Peričić T, Zajac J, Rohwer A, Klugarova J, Välimäki M, Lantta T, Pingani L, Klugar M, Clarke M, Young T. What are the effects of teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC) at different levels of health professions education? An updated overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254191. [CrossRef]

- Larsen CM, Terkelsen AS, Carlsen AF, Kristensen HK. Methods for teaching evidence-based practice: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):259. [CrossRef]

- Chiappelli F. Evidence-Based Dentistry: Two Decades and Beyond. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2019 Mar;19(1):7-16. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakoulis K, Patelarou A, Laliotis A, Wan AC, Matalliotakis M, Tsiou C, Patelarou E. Educational strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2016 Sep 22;13:34. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf nazir mu, almas k. Knowledge and practice of evidence-based dentistry among dental professionals: an appraisal of three dental colleges from lahore–pakistan. Pak Oral Dent J. 2015;35(3).

- Basharat S, Shaikh BT, Rashid HU, Rashid M. Health seeking behaviour, delayed presentation and its impact among oral cancer patients in Pakistan: a retrospective qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Oct 21;19(1):715. [CrossRef]

- Tiwana KK, Kutcher MJ, Phillips C, Stein M, Oliver J. Gender issues in clinical dental education. J Dent Educ. 2014 Mar;78(3):401-10. [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz R., Qazi SH, Sajjad S. Balancing Profession, Family and Cultural Norms by Women Dentists in Pakistan. Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2018;6: 154-170. [CrossRef]

- McKay JC, Quiñonez CR. The feminization of dentistry: implications for the profession. J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c1.

- Holden ACL. "Preparedness for Practice" for Dental Graduates Is a Multifaceted Concept That Extends Beyond Academic and Clinical Skills. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2020 Mar;20(1):101421. [CrossRef]

- Mohan M, Ravindran TKS. Conceptual Framework Explaining "Preparedness for Practice" of Dental Graduates: A Systematic Review. J Dent Educ. 2018 Nov;82(11):1194-1202. [CrossRef]

- Moore U, Durham J. Invited commentary: Issues with assessing competence in undergraduate dental education. European Journal of Dental Education. 2011 Feb;15(1):53-7. [CrossRef]

- Tuncer D, Arhun N, Yamanel K, Çelik Ç, Dayangaç B. Dental students' ability to assess their performance in a preclinical restorative course: comparison of students' and faculty members' assessments. J Dent Educ. 2015 Jun;79(6):658-64. [CrossRef]

- Gabbard T, Romanelli F. Do Student Self-Assessments of Confidence and Knowledge Equate to Competence?. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2021 Jan: 85(4);8405. [CrossRef]

- Pandarathodiyil AK, Mani SA, Ghani WM, Ramanathan A, Taalib R, Termizi Zamzuri A. Preparedness of Recent Dental Graduates and Final Year Undergraduate Dental Students for Practice amidst the Covid-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Dental Education. 2022 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Deery C. The COVID-19 pandemic: implications for dental education. Evid Based Dent. 2020 Jun;21(2):46-47. [CrossRef]

- Haroon Z, Azad AA, Sharif M, Aslam A, Arshad K, Rafiq S. COVID-19 Era: Challenges and Solutions in Dental Education. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020 Oct;30(10):129-131. [CrossRef]

- Ihm JJ, Seo DG. Does Reflective Learning with Feedback Improve Dental Students' Self-Perceived Competence in Clinical Preparedness? J Dent Educ. 2016 Feb;80(2):173-82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).