1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and social interaction, in addition to restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior and interests. In 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th (DSM-5) [

1] created the umbrella diagnosis of ASD, consolidating four previously separate disorders: autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome (AS), childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. Unlike previous versions, in DSM-5 more importance is placed on what is a developmentally oriented classification of childhood mental pathology, paying attention to the neurobiological etiology underlying these disorders. In this new classification, Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) is inserted into the Level 1 autism spectrum disorder, without intellectual impairment of the associated language [

2]. The characteristics of the subjects with this syndrome are: having special interests, reporting difficulties in social communication and social interaction, having an Intelligent Quotient > 70, having an early and formal language development, but lack of pragmatics of communication. Recently, data from the American Centers for Disease Control (CDC) indicate at 8 years a prevalence of 1 out of 134 children [

3], i.e., about 0.75%.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. It is a public health emergency of international concern and poses a challenge to psychological resilience [

4]. It is necessary to understand the psychological impact that the epidemic itself and relative quarantine have on the entire population, especially children and young people with disabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic has led families to adapt their lives, including social isolation and work from home. The consequences of this outbreak on mental health are several. Change in routine is often a significant challenge for children with ASD [

5], and for that reason, families with children with ASD could be a vulnerable group to develop anxiety and mental abnormalities during quarantine and isolation. Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often experience changing routines as a major challenge. For that reason, the need for adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic may have brought great problems to families with children with this pathology. Children with ASD are at high risk for psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the degree of understanding of the child of COVID-19, COVID-19 illness in the family, low family income, and depression and anxiety symptoms in parents increase the risk of poor mental health during the pandemic [

6]. The results of recent studies showed a potential important psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic not only in children with neurodevelopmental disorders, but also in their caregivers, especially anxiety symptoms [

7]. Parents of children with ASD had lower levels of resilience and more symptoms of anxiety and depression than parents of children typically developing [

8].

The strict domestic quarantine policies adopted to control the transmission of COVID-19 could have adverse psychological effects and could exacerbate preexisting conditions such as depression and anxiety, especially in people with mental disorders [

9]. Lockdown and boredom can reveal a susceptibility to unhealthy behaviour.

During quarantine, in addition to sociodemographic factors, the factors that seem to affect the worst psychological impact are: the duration of quarantine [

10,

11]; the fear of being infected and of being able to infect others [

12,

13]; boredom and frustration caused by the loss of daily routine and the reduction of physical and social contacts [

11,

14]; the lack of basic necessities (food, water, clothes) [

15,

16]; the scarce and inadequate information [

14,

17].

The numerous changes in the daily life of every single citizen with the lockdown have mainly been: school attendance, social and family relationships, also of children and young people both normal and with pervasive developmental disorders who have had to become aware of the health emergency.

In the adolescent population, some consequences in their health could be: sedentary behavior that increases proportionally to Covid19 screen exposure [

18], decreased physical activity time [

18], increased insomnia and sleep-related problems [

19] and increased difficulty falling asleep and sudden awakening episodes [

20]. Also, from the point of view of psychic and psychological problems, adolescents seem to have been influenced by anxiety symptoms, and some studies show some influence on the anxiety levels of suicidal thoughts.

Research Questions

Our interest focuses on the entire family unit of adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome who, like their peers, have had to adapt to quarantine especially to distance learning, but also to online rehabilitation activities during the period of isolation. There are limited studies on this population, for this reason, it is important to have a picture of their perceptions about risk and preventive or protective behaviors both during quarantine retrospectively and in school reintegration and social life.

The research questions are the following:

H1) Do children and young people with Asperger syndrome have a good understanding of the risk of COVID-19 and of the preventive measures to contain it?

H2) What were the possible psychological consequences, in children with Asperger’s and in their parents during quarantine?

H3) What have been the main difficulties for children and young people with Asperger’s syndrome in returning to school and resuming social life since September 2020?

H4) Could the high parental stress experienced during the lockdown have influenced in the long term the emotional and behavioral difficulties their children have experienced with returning to school and everyday life since September 2020?

3. Results

3.1. Knolewdge typically and Asperger adolescents about Coronavirus and anti-COVID rules

Paired-sample Wilcoxon tests were run to see the possible differences between right and wrong answers in the two groups. The mean ranks within the groups were significant, both for the clinical group Z = -3.50, p<0.001 and for the control group Z = -3.43, p = 0.001. The entire group of participants analyzed the answers, on average, correctly to a greater number of questions.

On the other hand, the comparison between the means of the ranks of the two paired samples of correct answers between groups appears to be insignificant Z = -1.89, p = 0.85. Thus, we demonstrate how the boys in both groups respond correctly on average to the same number of questions on the COVID-19 test

3.2. Possible psychological consequences in children with Asperger’s and in their parents during quarantine

First, a paired sample Wilcoxon test was performed to identify possible differences in perceptions of life between the two groups. The two groups didn’t show differences in their life perception scores (Z=.13, p=.90), showing an insufficient one in 53.3% of cases, a sufficient one in 26.7% and very good in 20% of cases.

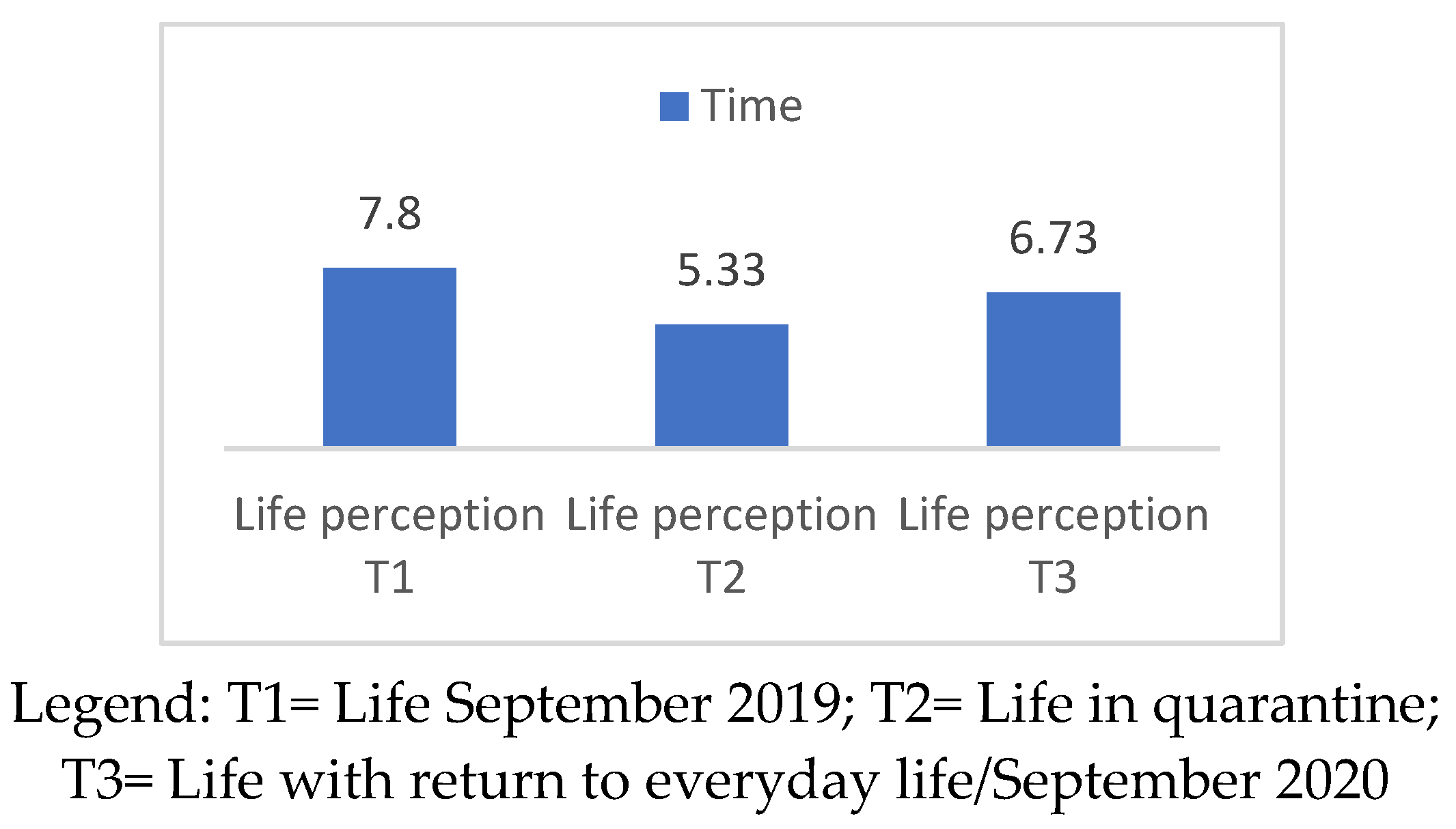

In the clinical group, on a statistical level, no significant differences emerged between the scores attributed to one’s own life between T1 and T2 (Z=-1.44, p=.15); between T1 and T3 (Z=-.99, p=.32); and between T2 and T3 (Z=-1.21, p=.23). While for neurotypical children, no significant differences emerged between the scores attributed to one’s life between T1 and T3 (Z=-1.59, p=.113); instead we find significant differences between T1 and T2 (Z=-2.12, p=.034) and between T2 and T3 (Z=-2.29, p=.022). These results, related to the neurotypical group, were investigated using repeated measures ANOVA, in which the data did not satisfy the sphericity hypothesis of the Mauchly sphericity test [W(2)=.61, p=. 04], thus using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction criteria, a significant difference emerged between the three Cantrill scales in the different time periods investigated [F (1.44) = 5.47, p = 0.020], which can be observed in

Figure 1.

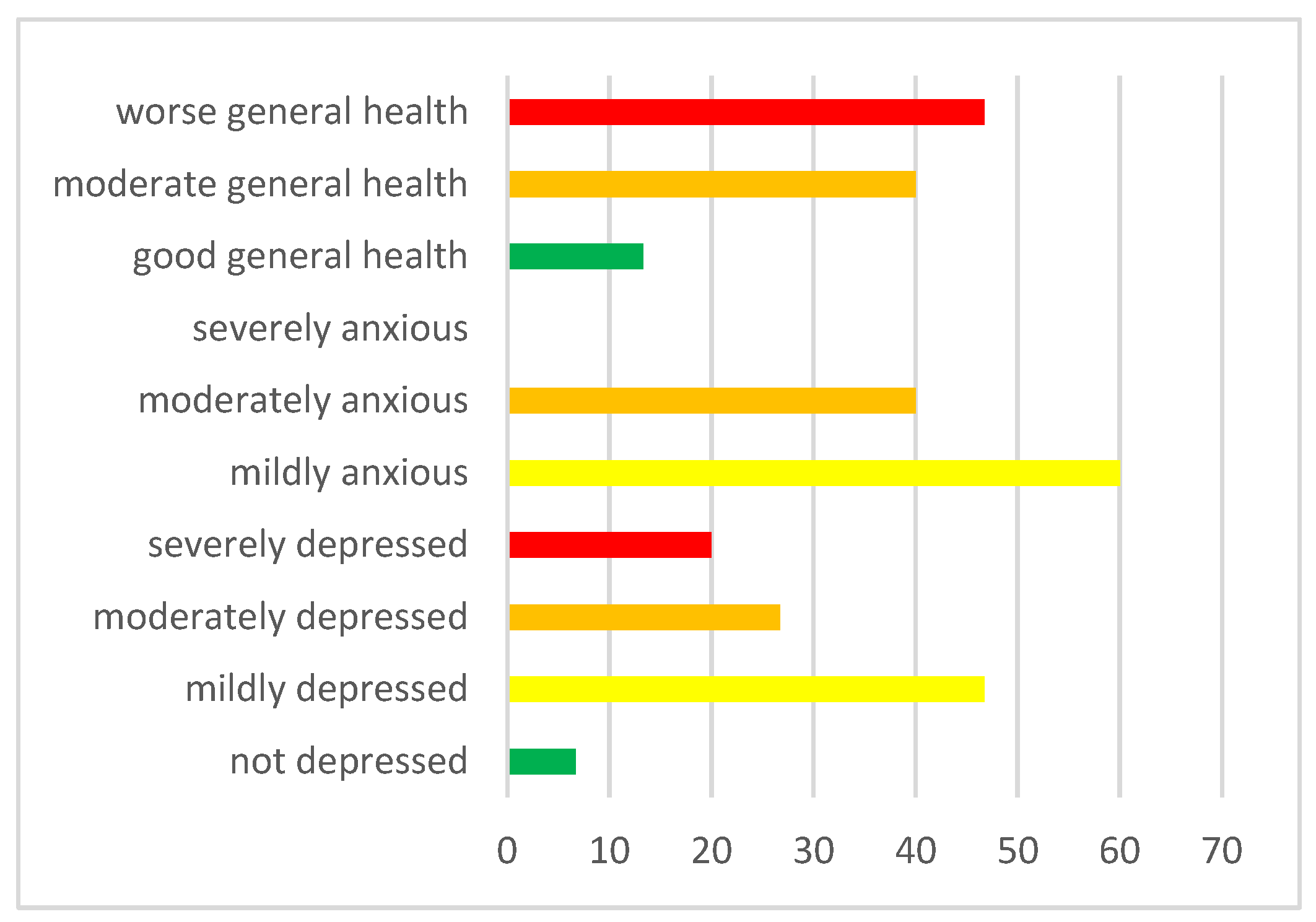

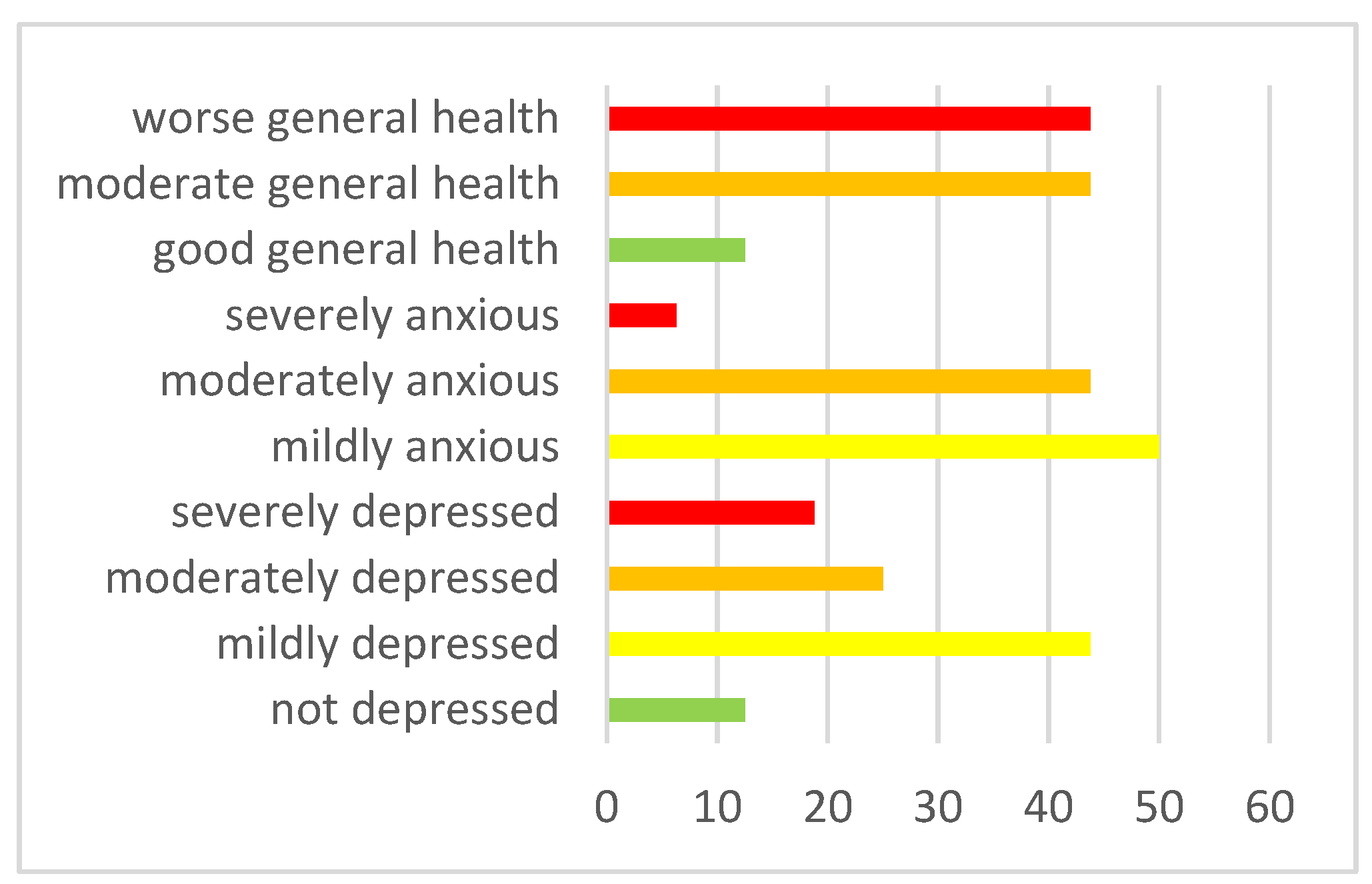

Then, the Wilcoxon rank test was run on paired samples to understand whether parents with Asperger’s children experienced the same stress and worsening of well-being as parents with neurotypical children. <this was followed, because there were no significant differences in depression (Z=-.347, p=.729), anxiety (Z=-.918, p=.359) and well-being (Z=-1.06, p=.291) between the two groups of parents (clinical and control). See Figure 2a for the clinic group and Figure 2b for the control group.

Figure 2a. Parents symptomatology in the clinic group.

Figure 2a. Parents symptomatology in the clinic group.

Figure 2b. Parental symptomatology in the control group.

Figure 2b. Parental symptomatology in the control group.

3.3. Main psychological difficulties for children and young people with Asperger syndrome with returning to school and resuming social life since September 2020

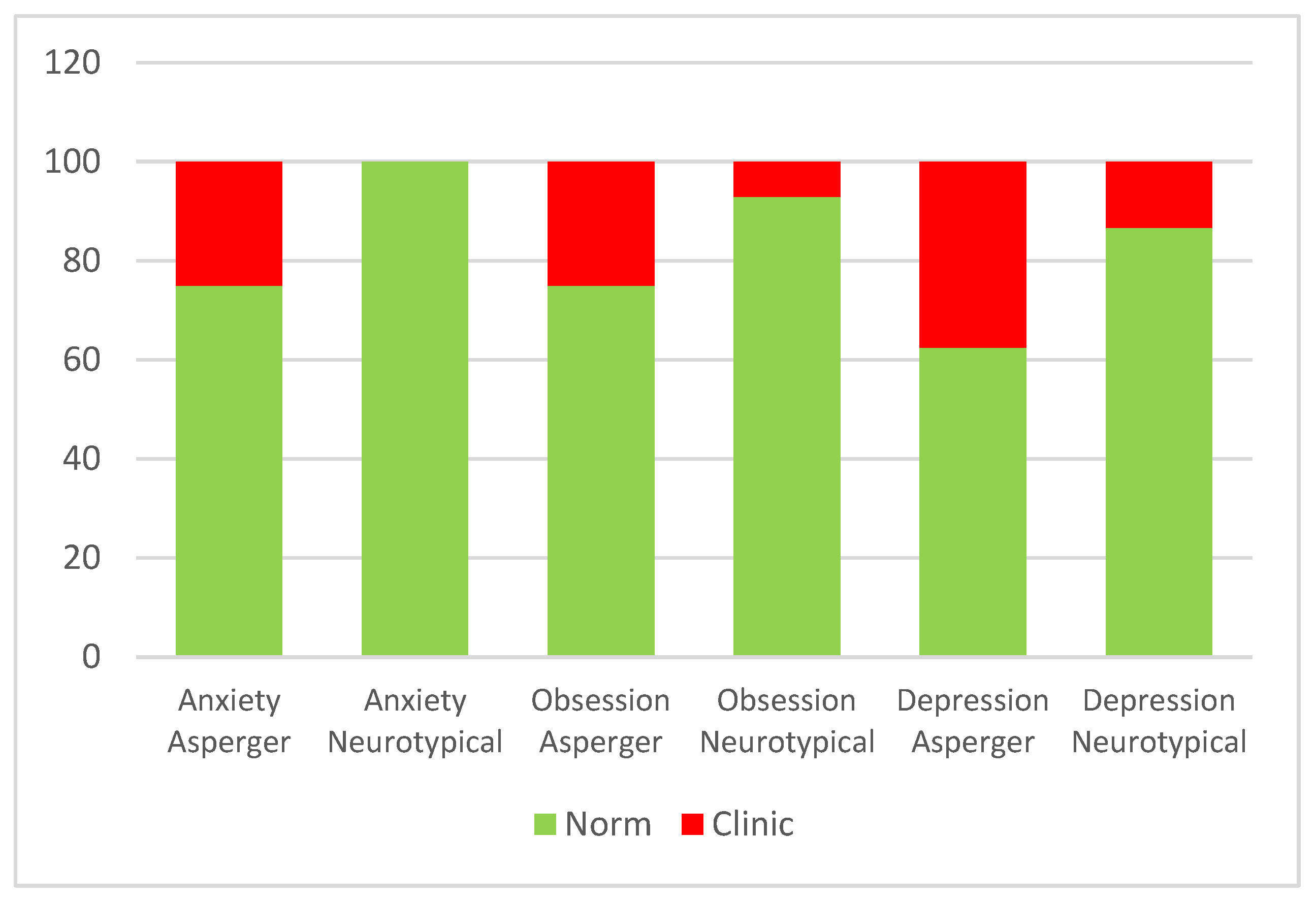

The Wilcoxon rank test for paired samples was calculated. The aim was to evaluate the presence of a significant difference in anxiety, depression, and obsession scores between the clinic and control groups.

The comparison between the rank means of the two matched samples was significant only for the SAFA subscale related to anxiety (Z = -2.59, p = 0.01), where neurotypical adolescents reported, on average, higher scores (Mean = 8.12) compared to the control group (Mean = 7.25). Figure 3 shows the placement at the normal or clinical level for both groups on all SAFA scales.

Figure 3.

Placement at the normal or clinical level for both groups on all SAFA scales.

Figure 3.

Placement at the normal or clinical level for both groups on all SAFA scales.

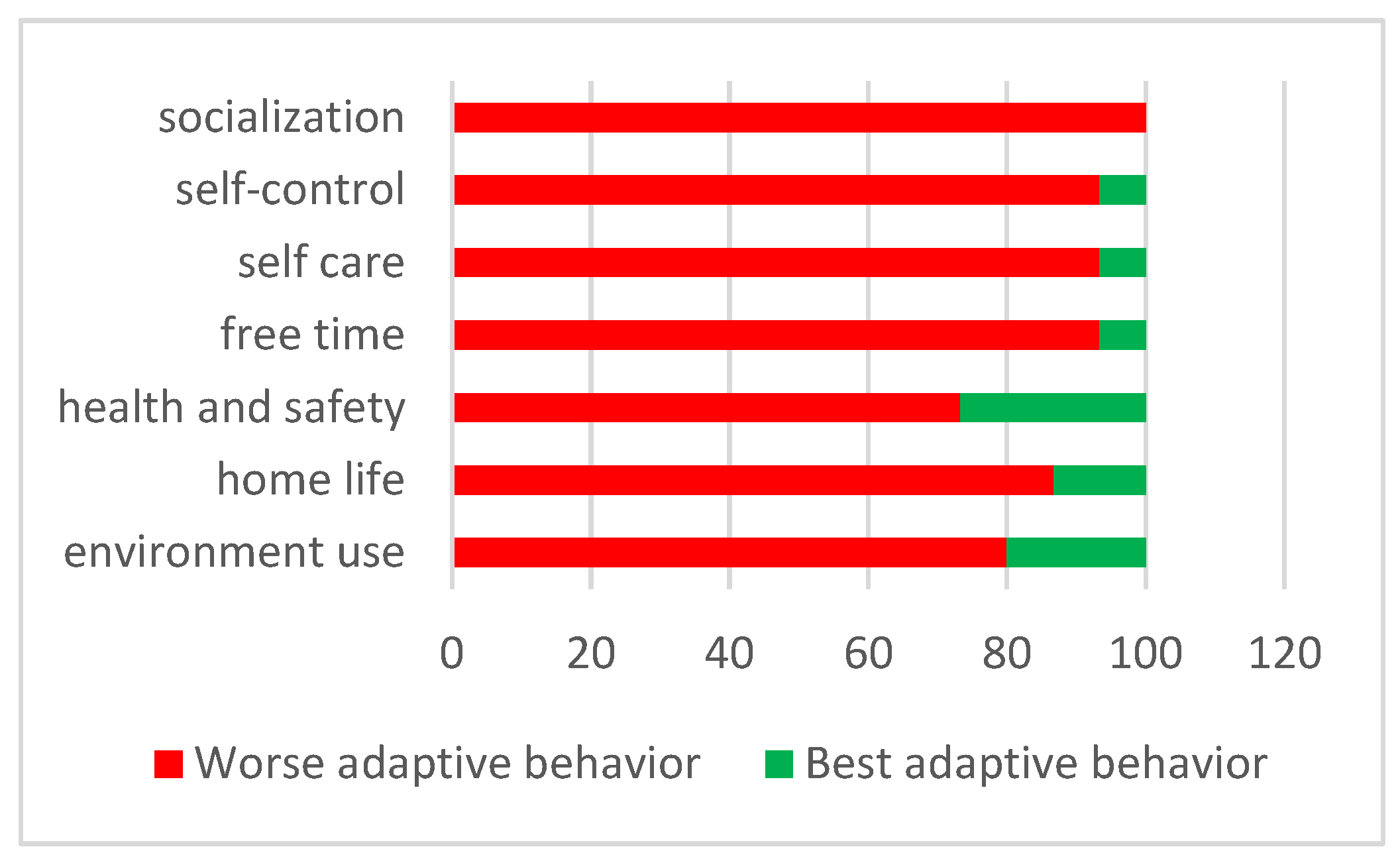

However, in terms of the adaptive behavior of Asperger’s children assessed by their parents, the worst adaptive behaviors were several, especially the area of socialization, evaluated by all parents as the area with the worst adaptive behavior (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Placement in the worst or best adaptive behavior in ABAS-2 scores in the clinic group.

Figure 4.

Placement in the worst or best adaptive behavior in ABAS-2 scores in the clinic group.

Only secondarily, a series of two paired samples Wicoxon test were run to analyze whether there was a significant difference in each adaptive behavior scale along the belonging on clinic or control group. Differences were found for the General Adaptive Composite GAC (Z = - 2.55; p = 0.01), Conceptual Composite CC (Z = - 2.13; p = 0.3), Social Composite SC (Z = - 3.11; p = 0.002) and Practical Composite PC (Z = - 2.36; p = 0.02).

The clinic group members had significantly lower averages in GAC (M=60.43; SD= 12.92) than the second group (M = 74.12; SD= 10.58), in CC (M= 55.22; SD= 5.33 versus M= 61.17; SD= 3.56), in SC (M=65.13; SD=11.03 versus M=83.38; SD=14.88) and in PC (M= 69.33; SD=20.22 versus M=87.25; SD=12.67).

3.4. The high parental stress experienced during the lockdown influenced the emotional and behavioral difficulties when children experienced the return to school and to everyday life since September 2020

For the Asperger group, a significant correlation was found between parental depression scores during lockdown and children’s anxiety subscale scores related to school return since September 2020 (r(13) = 0.56, p=.029). For the neurotypical group, a significant correlation was found between the questionnaire scores on the well-being perceived by their parents during quarantine and the scores related to the perception of life that adolescents themselves attribute to the "current moment" (r(13) = - 0.57, p = 0.02).

4. Discussion

What motivated this study was to try to give a greater voice to children and young people with Asperger syndrome (clinical population still little investigated from the point of view of the literature) with regard to their perceptions and evaluations at a retrospective level during the lockdown and their understanding of the anti-COVID rules. Above all, we wanted to investigate the long-term consequences associated with the resumption of everyday life. Furthermore, taking into consideration the entire family unit and comparing it with families with neurotypical children, the secondary aim would be, through a comparative analysis, to prepare ad hoc guidelines for parents and teachers on how to support and help children with Asperger’s, the behaviors to follow and the management of safe and secure behaviors in schools and in relationships with others; but also to give feedback to the operators of their centers of afference.

The psychologists of the center had underlined a notable characteristic of Asperger children, namely the diligent respect of rules and duties after they had been explained in a language they could understand. These explanations were given not only by the psychologists and parents, but also by the school, which assumed a fundamental role in the prompt provision of various information on COVID-19 and the support of adolescents. This feature had allowed hypothesizing an adequate knowledge and constant implementation of the anti-COVID rules confirmed by the results of the ad hoc questionnaire on perceived risk. In fact, the data confirm a good understanding and application of the regulations by the Asperger participants on the same level as their neurotypical peers, precisely out of a total of 42 questions both groups correctly answered on average 35 questions. In particular, the former correctly answered 83.6% of the questions, while the neurotypical peers 84.3%.

Regarding the second area of investigation, aimed at identifying the consequences, in terms of perceived stress, of family members of the population with Asperger’s during the quarantine; two research questions were analyzed separately. Our expectations, regarding the greater well-being of Asperger’s children in quarantine, were only partially confirmed. In fact, from their point of view, the perception of life in quarantine is estimated, like neurotypical peers, in 53.3% with an insufficient vote; this tends to fade in the post-quarantine period, however remaining higher in Asperger boys (33.3%) than in neurotypical (26.7%). In fact, adolescents in the experimental group on average, as those in the control group, perceived greater discomfort during quarantine, not benefiting as uniformly from social distancing as in those with neurological disorders [

31]. Although more in line with our expectation relating to the third research question, which foresees greater difficulties for the clinical group from September 2020, Asperger’s children perceived their life more negatively than their neurotypical peers, precisely in the period of the resumption of daily activities such as, for example, school in attendance.

Although the perception of life during quarantine has an insufficient assessment for just over half of Asperger’s children, it is not excessively high since, at the individual and family level, functional strategies have been implemented to better deal with the pandemic situation. On the one hand, adolescents uniformly declared that they perceived benefits in terms of limiting travel and extracurricular activities by obtaining more time for themselves by focusing on their special interests; on the other hand, parents have tried to reconstitute stable and positive routines such as moments of family conviviality during meals, "virtual workouts" and activities games, becoming important protective factors for the entire family unit [

32,

33,

34]. Furthermore, these new routines have made it possible to better regulate and discharge the emotionality of the children, thanks to the active and moderate participation of the parents themselves [

35], but also to specifically reduce two anomalous behaviors of the children reported in the lockdown questionnaire, such as: irritable behavior and lack of appetite.

Parents of atypical development [

36] reported, as parents of children with neurotypical development [

35], negative effects in terms of increased stress and worsening mental health. This hypothesis was fully corroborated. In fact, in both groups, it was possible to highlight symptoms, although not excessively elevated, of anxiety and depression (higher frequency between mild and moderate), and in most parents a deterioration of well-being during quarantine. Furthermore, no significant differences were identified between the symptoms of the parents and the age groups of the children and also regarding the symptoms between the two groups of parents.

The investigation of the third research area on the difficulties in Asperger’s children identified with the resumption of everyday life from September 2020) only partially confirmed our hypothesis. In fact, as already expressed above, children with Asperger syndrome evaluate their lives by referring to the present moment with an insufficient vote in 33% of children, while the remaining percentage has medium-high evaluations. This lack of homogeneity of response can be explained by the fact that Asperger’s children, while expressing, in most of the interviews, happiness in returning to school and in resuming activities in the center of reference, however, compared to their neurotypical peers, they constantly experience a high sense of uncertainty linked, albeit minimally, to having to get used to face-to-face activities and, moreover, to the possibility of returning to DaD and therefore in quarantine or of being able to contract COVID in the face of a still deep-rooted health emergency.

These concerns are revealed by the presence, in Asperger’s children, of depressive (37.5%) and anxious (25%) symptoms related to the possibility of returning to quarantine and obsessive (25%) symptoms related to the possibility of contracting the virus, which leads them to diligently implement, and also ask others to respect, all the anti-COVID rules (wash your hands, do not touch other people’s objects, then the mask or your eyes, etc.). Specifically, all three symptoms are higher than in the control group; especially anxiety does not appear to be clinical for the neurotypical sample; while in both groups, obsessive symptoms appear to be higher in boys between 15 and 20 years of age.

This symptomatology supports the results of studies conducted on neurotypical and neurological adolescents, in which direct effects of COVID related to anxiety, depression [

37], and obsessions [

31,

38]; in the quarantine period and immediately after. It was hypothesized that these consequences could also be found in the long term, an aspect traced in our study with reference to the Asperger population and the period from September 2020.

The results obtained for the fourth and last research area confirmed partial cumulative effects of parental stress during quarantine and behavioral and emotional imbalance with return to school from September 2020, in the knowledge that parental stress had already negatively influenced their own children [

20,

35,

39,

40]. Specifically, it seems that in children with Asperger syndrome the greater depressive symptoms of the parent during quarantine, also due to the difficulties in reconciling work and support for the DaD, have a more negative influence on anxiety symptoms (albeit moderate) related to the return to daily life in children between the ages of 10 and 14. Probably, the guys from this age group, also in the face of a greater possibility of attending their own institutions in person more than older children, could perceive more anxiety related to a situation of returning to DaD and "locked up at home" by taking siblings as an example or rather older friends, compared to a greater "resignation" to the situation for the latter.

A narrative of an adolescent explains well this concept: ’We really wanted to go back to school, I was delighted to see everyone again, with a little fear that we might attack COVID’ - “At first I was intrigued about what it would be like to go back to school and I was dubious about what it would be like to do it with masks… it went well and I was happy!” - “I was delighted to go back to class; however, it took me some time to get used to the situation again. It has been a beautiful few months but we were all always anxious for the other risk of being able to return to DaD from one day to the next, as in reality then it happened!".

In neurotypical adolescents, a lower well-being perceived by parents during quarantine correlates with a lower evaluation that the boys themselves give to their lives in the current moment; in particular, it seems to be the older boys who express these evaluations, thus perceiving even greater effect of the well-being experienced in quarantine by their parents.

Strengths and Limits

One of the limitations of this research is certainly the number of participants and the gender and age characteristics of the sample, which do not make the results sufficiently generalizable. The sample made up of 16 Asperger’s children paired with neurotypically developed children must, however, take into account both the niche clinical population that we have tried to recruit in the project, and the historical context in which entire families have found themselves facing the overwhelming and disharmonious everyday life, which could have undermined the greater adherence to research.

An aspect of particular relevance is the fact that the participants are all males and there is little heterogeneity as regards their age and distribution in the three academic ranges (primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary schools). It would be interesting to extend the survey also to girls with Asperger syndrome, albeit of lesser diagnostic importance precisely because they are very often underdiagnosed and at the same time make the age groups of the participants more homogeneous.

A second important limitation was the large number of items to which the boys were subjected; specifically the application of three subscales of the SAFA (anxiety, depression, and obsessions) made it more difficult to maintain the attention of the participants and lengthened the time required to complete the questionnaire, especially for the adolescents in the experimental group.

Finally, the predominantly transversal data collection that refers in many respects to the present moment, integrated with specific questions and questionnaires in which they are asked to recall aspects related to the more remote past (September 2019) and more recent (during quarantine) has encountered considerable difficulties in the Asperger population regarding the temporal aspect of the past.

Despite these limitations, we can identify three strengths of the research: the first is related to the fact that the research itself is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate difficulties during quarantine but, above all, the long-term effects of the measures determined from the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic in Asperger children and teenagers and the perceived difficulties with returning to everyday life. A second merit is that we conducted the survey on families in Veneto, one of the most affected areas on the national territory, to highlight the consequences in a context in which there has been a greater incidence of COVID. With reference to the latter aspect, it would be interesting to be able to estimate the presence of differences that we could find in families with the same atypical population but in central-south regions of Italy.

Finally, a last and great advantage is highlighted by the use of the mixed and multi-informant approach. The first allowed us to delve into the narrowest niche of Paduan families, aspects more generally investigated through questionnaires, both as regards Asperger’s children and their parents; the second, through the involvement of significant family members, has allowed us to better enrich not only the individual but also the family picture.

In a future perspective, not too distant, it could be interesting to include support teachers in the study, with the aim not only of investigating their experiences in quarantine with the DaD and the fluctuating and partial recovery of the presence for most of the new academic year; but also of highlighting their role for Asperger’s children and highlighting aspects of greater management difficulty that could be supported by ad hoc guidelines.

Furthermore, for future studies, it would be more necessary to reduce the workload required for the recruited clinical and neurotypical population.

Finally, starting from our results, it could be interesting to investigate in the same group of participants one year from today whether and for how long the symptoms persist, making this study a starting point for a possible longitudinal study of the consequences of a pandemic that has marked, like a scar, the experience of each of us.