Introduction

Fermentation plays a significant role in the traditional processing of food in many parts of the world. In many developing countries, traditional fermentation also serves as the method for improving the shelf life of many staple foods, whilst improving their digestibility, nutritional qualities, organoleptic properties and degradation of toxins and antinutritive factors (Zang et al., 2020, Maicas 2020, Adebo 2020, Voidarou et al., 2020). However, in Ghana and many parts of Africa, traditional fermentation processes are natural, that is, without the use of starter cultures (back slopping), which have implications for the safety and quality of the products (Wirawati et al., 2019, Kim et al., 2018, Özel et al., 2020, Venema & Surono, 2020).

In Ghana, naturally fermented milk is commonly produced and consumed by people living in cattle-rearing communities (Agyei et al., 2020, Motey et al., 2021, Sessou et al., 2019, Ayivi et al., 2020). The production of traditional yogurt-like milk products in Ghana does not rely on the use of commercial starter cultures. Therefore, stocks of previous ferments, fermentation containers, and environmental microorganisms contaminating the raw material often initiate fermentation in new batches (Owusu-Kwarteng et al., 2020). During the process, raw or pasteurized milk is kept in calabashes or plastic containers, covered with a lid, and allowed to spontaneously ferment at ambient temperature (28-35°C) for about 18-24 h. This natural fermentation results in the formation of curdled milk, yielding a slightly sour yogurt-like product with pH of less than 4 and varying consistency (Agyei et al., 2020, Motey et al., 2021, Sessou et al., 2019, Ayivi et al., 2020, Owusu-Kwarteng et al., 2020).

Generally, the dependence on such an undefined and diverse microbial consortium during fermentation results in products with inconsistent quality and stability (Abi Khalil et al., 2022, Galli et al., 2022). In a framework to develop starter cultures for controlled fermentation and production of fermented yogurt-like milk with greater consistency in quality and safety, it is required that LAB cultures for commercial and consistent fermentation processes are adequately propagated and made available as concentrates, either in a frozen or freeze-dried form (Vinderola et al., 2019, Chen & Hang 2019). Concentration and preservation of LAB starter cultures for food production rely on technologies, which guarantee the long-term delivery of stable cultures in terms of viability and functional activity (Brizuela et al., 2021, Terpou et al., 2019, Fonseca et al., 2019). Thus, the preservation technique of the collected bacterial cultures must ensure that the recovered starter cultures perform in the same manner as the originally isolated species (El-Dein et al., 2022).

One method that has commonly been used to prepare dried starter cultures for food applications is freeze-drying (Sandhya & Disha, 2020, Guowei et al., 2019, de Melo Carvalho 2019). In this process, dehydration of LAB imposes environmental stress on the bacterial cells, such as freezing, drying, long-term exposure to low-water activities and rehydration. Microbial survival during this process depends on many factors, including the intrinsic resistance traits of the strains, initial concentration of microorganisms, growth conditions, drying medium and protective agents, storage conditions (temperature, atmosphere, relative humidity) and rehydration conditions (Estilarte et al., 2021, Jeantet & Jan, 2021, Wang et al., 2019, Noguerol et al., 2021). Currently, there is little or no study that has reported on the survival performance of freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria cultures isolated from traditional Ghanaian fermented milk. Previous investigations on Ghanaian fermented milk products have focused on isolation and characterization of the predominant microorganisms to develop starter cultures for improved fermentation, food safety and quality (Agyei et al., 2020, Motey et al., 2021, Sessou et al., 2019, Ayivi et al., 2020, Owusu-Kwarteng et al., 2020). The purpose of this study, therefore, was to evaluate the survival rates and fermentation performance of indigenous lactic acid bacterial cultures, isolated from traditional Ghanaian fermented milk, following freeze-drying. Furthermore, the effects of different drying medium (skim milk & cassava floor) and storage condition (ambient & refrigeration) on the survival and performance of the freeze-dried LAB cultures were also determined.

Methodology

Study Design

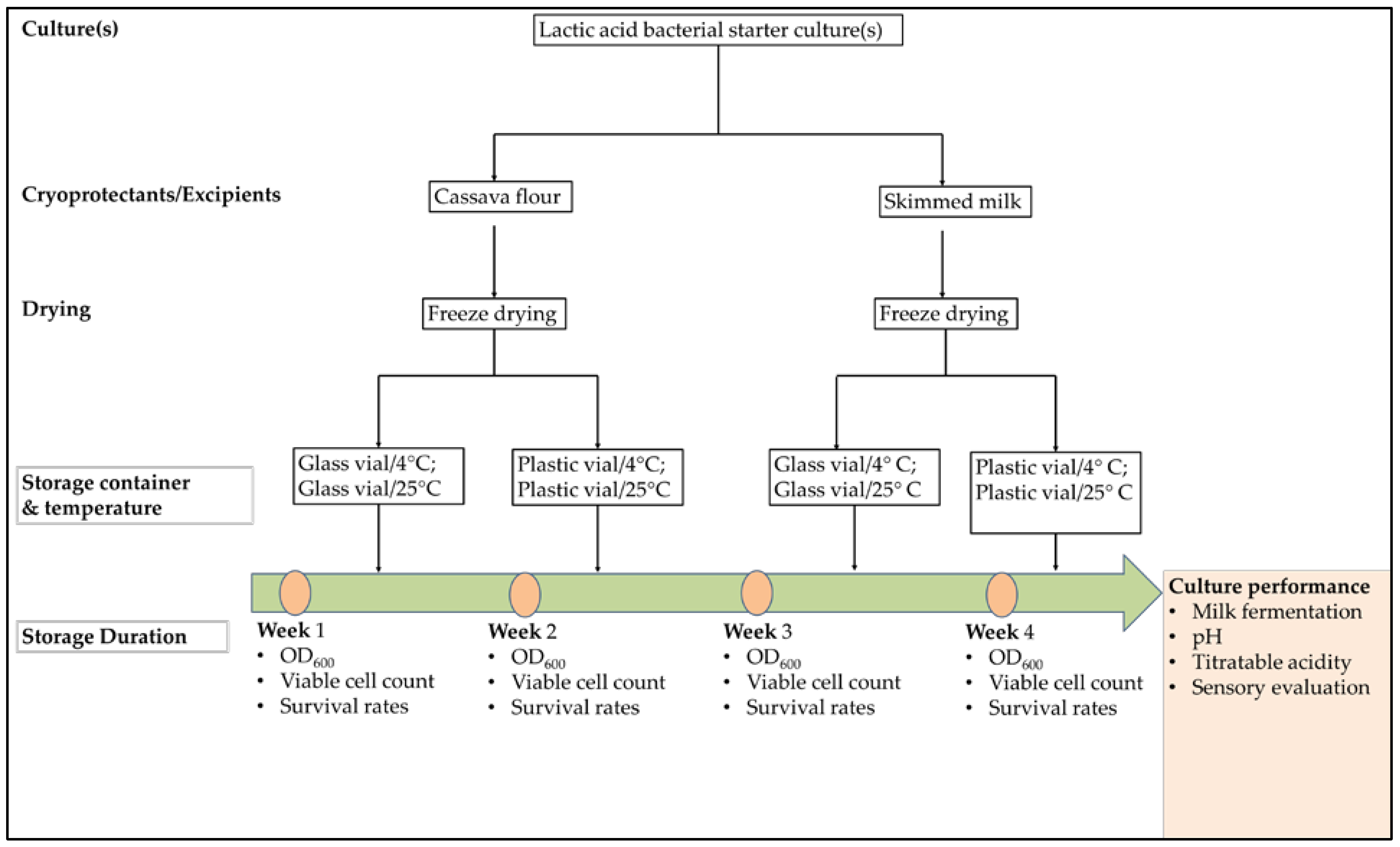

A schematic representation of this study is shown in

Figure 1. Previously isolated identified lactic acid bacterial strains or their combinations were treated with cassava flour and skimmed milk as cryoprotectants for freeze-drying. Following freeze-drying, the cultures were stored in plastic or glass containers and stored under different temperatures (4 °C and 25 °C) over four weeks and monitored for their survival rates. Furthermore, the cultures were assessed for their fermentation performance in yoghurt production.

Lactic acid bacterial strains

The strains used in this study include Lactococcus lactis (L3), L. delbrueckii (L12), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) and their combinations (L3 + L12, L3 + L20, L12 + L20, L3 + L12 + L20). The strains were isolated from spontaneously fermented milk obtained from Navrongo and Accra in Ghana. The LAB strains were previously identified by sequencing of sequencing of the 16S rRNA and in MRS broth with 20% glycerol at – 20°C as stock cultures.

Preparation of Cultures for freeze-drying

Lactic acid bacterial cells were separately grown in 200 mL MRS-broth in Erlenmeyer flasks at 35 °C anaerobically for 24 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation (Labofuge200) at 5000rpm for 10 mins. The harvested cells were washed in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and initial concentration (Optical Density, OD600) of the cells was determined using a spectrophotometer (SM22 PC, SurgienField instrument, England).

Preparation of freeze-drying career materials

Skimmed milk powder (20 g) as an excipient was reconstituted in 100 mL of distilled water and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 mins, and cassava flour (20 g), was oven sterilized at 160 °C for 30 mins before mixing with 100 mL distilled water. Reconstituted excipients were allowed to cool to room temperature. The harvested lactic acid bacterial cells were suspended in the reconstituted excipient solutions and aliquoted (500 µL) into 1.8 mL glass and plastic vials.

Freeze-drying procedure

LAB samples in glass and plastic vials were frozen in the chamber of a Telstar (Lyoquest) laboratory freeze dryer for 10 h at -55 °C. Vial caps were removed after the freezing was completed and replaced with 100% PTFE thread seal tape (ISO CERTIFIED 19MM x 0.10mm x 20M) procured from Navrongo market and holes were made on the seal using a sterilized needle procured from Navrongo market.

The LAB samples were loaded in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask supported with cotton on the inside and held at the manifolds of the freeze-dryer and subsequently dried in the freeze-drier using the same Telstar laboratory freeze dryer under a vacuum pressure of 100mtor (1.33mbar) for 20 h. LAB Samples were disconnected from the freeze-drier and the sealed tapes were immediately replaced with the caps of the cryovials to avoid contamination. Cell viability was measured immediately after freeze-drying and this represents the initial (Day 0) of cell viability.

Storage conditions for freeze-dried cultures

The LAB samples were divided into two equal portions, with each portion containing equal samples held in a plastic and glass vials. Part of the LAB samples were stored in the refrigerator (refrigerated condition) and the other half was stored at room temperature (ambient condition). A weekly viability study was conducted on the stored LAB samples for four weeks.

Viability assays

Measurement of optical density (OD)/viable cell counting

Initial cell concentration (optical density) was determined using a spectrophotometer (SM22 PC, SurgienField instrument, England) for cell viability and survivability at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600). A plastic reusable cuvette was used to hold the samples to be measured in the spectrophotometer machine. The cuvette was wiped with clean cotton soaked in ethanol before the next measurement is taking to avoid cross-contamination. OD600 values were measured after the first week of storage, and the experiment was repeated for three more times (once every week).

Determination of survival rates

The percentage survival of the strains after the freeze-drying process was expressed as follows:

Survival % = Ni / Nf X 100

Where Nf is the CFU/g at the end of freeze-drying and Ni is the CFU/g before freeze-drying (at the end of centrifugation) (Yao et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times and raw data generated were entered into excel spreadsheet for further processing and management. Descriptive statistics including bar charts and line (time-series) graphs were used to analyse survival rates and performance of freeze-dried LAB cultures. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the means. Means were separated by Tukey’s family error rate multiple comparison test using the MINITAB statistical software package (MINITAB Inc. Release 14 for windows, 2004), and differences in means were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Viability of single strains Lactic Acid Bacteria after freeze-drying.

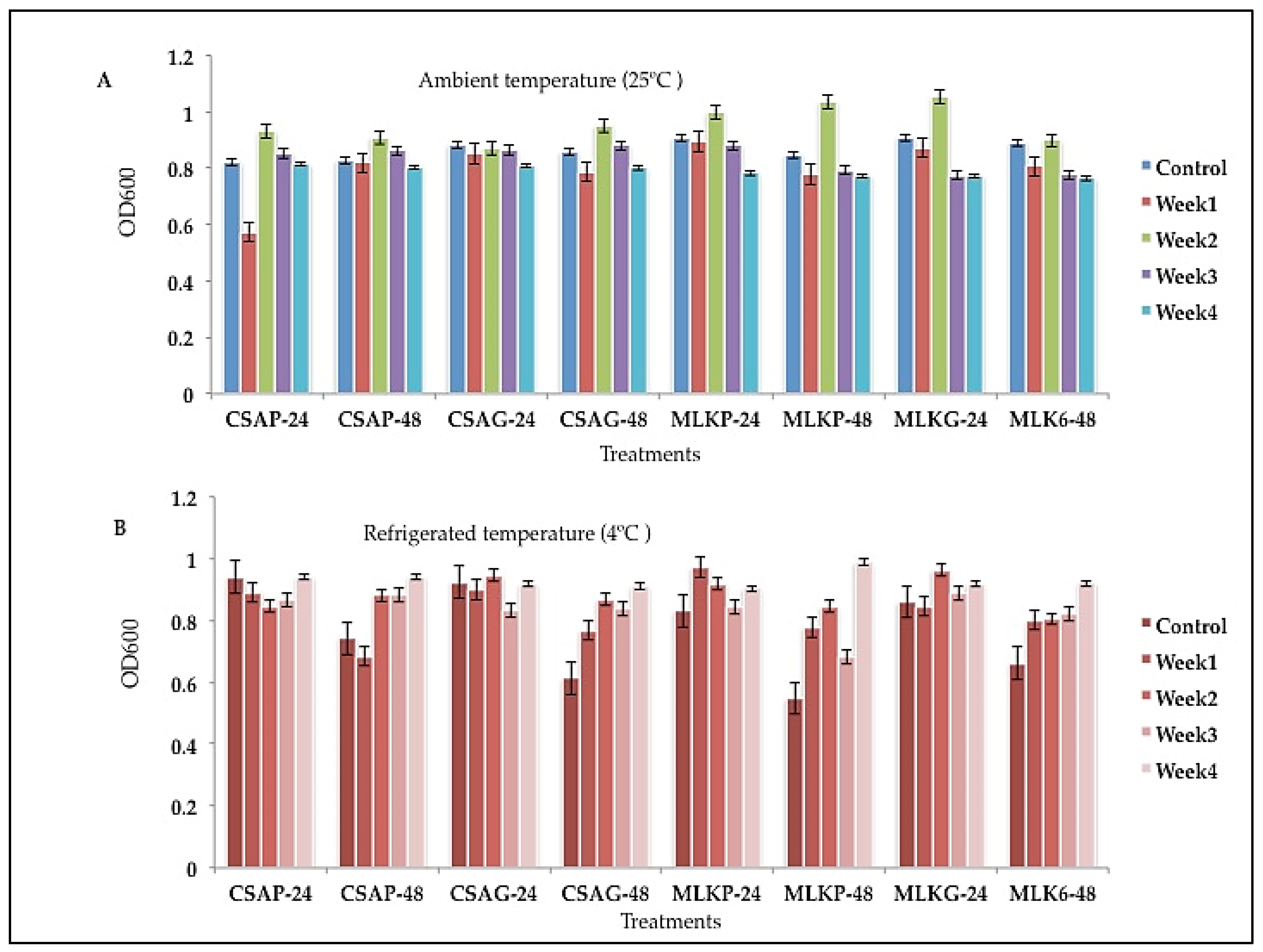

Single strains of lactic acid bacteria,

Lactococcus lactis (L3

),

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12), and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) were freeze-dried in two different kinds of excipients (cassava-CSA and skimmed milk-MLK) and in two different kinds of storage material (Plastic-P and Glass-G) to ascertain which treatment/condition best suits or support the functionality and viability of the lactic acid bacteria after a period of four weeks following freeze-drying. The Result’s showed that both

Lactococcus lactis (L3) (

Figure 2) and

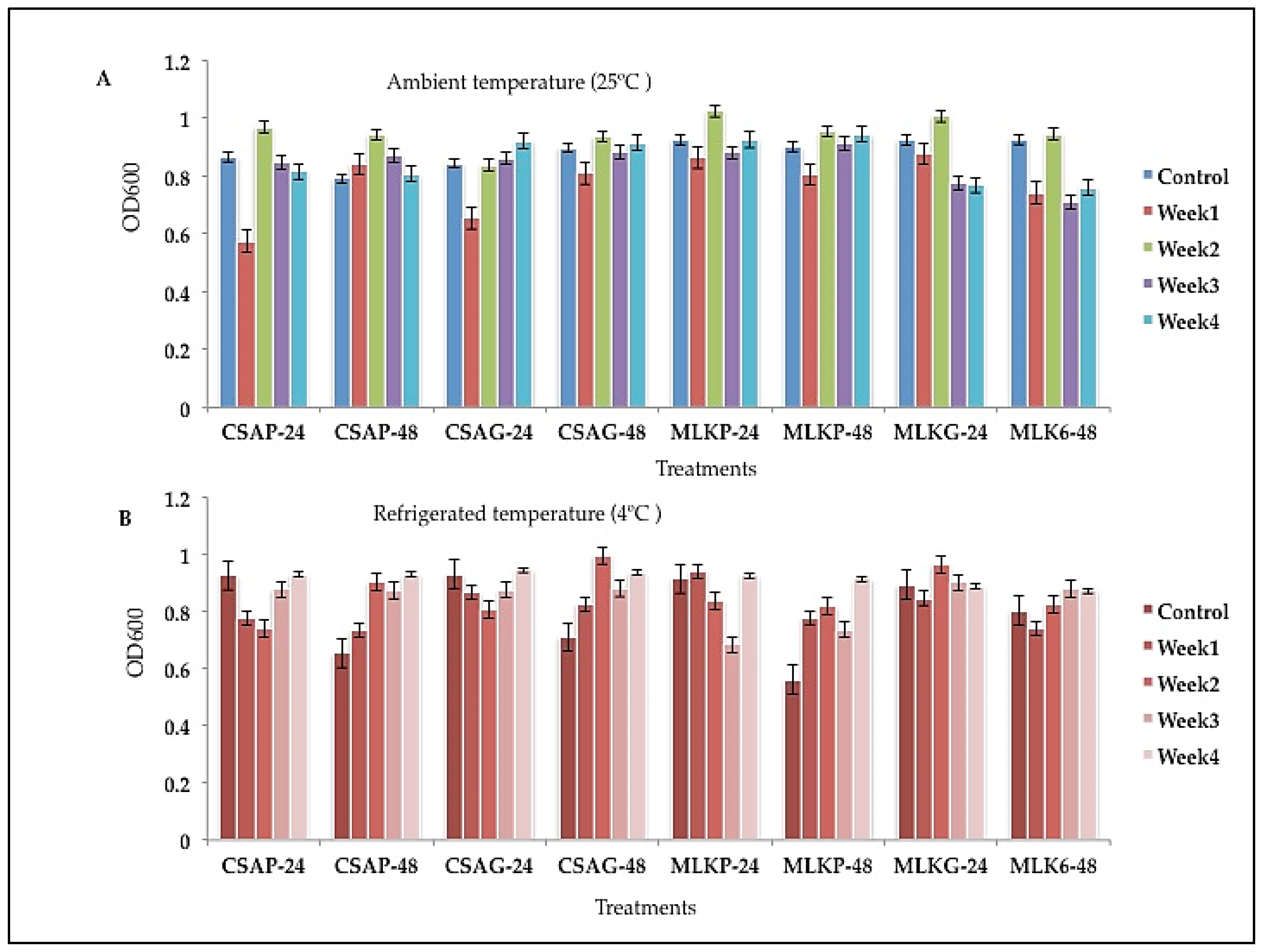

L. delbrueckii (L12) (

Figure 3) survived very well in cassava using plastic as the storage material (CSA_P) representing 68.87% and 70.91% respectively and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) (

Figure 3) survived well in skimmed milk under glass as the storage (MLKG) material representing 68.36% immediately after freeze-drying (control).

L. delbrueckii (L12) survived highly (

Figure 3) (70.91%) when treated with cassava with plastic as the storage container as compared to the other cultures immediately after freeze-drying (Figure 3) immediately after freeze-drying (Control).

Viability of single strains lactic acid bacteria following freeze-drying after weeks of storage.

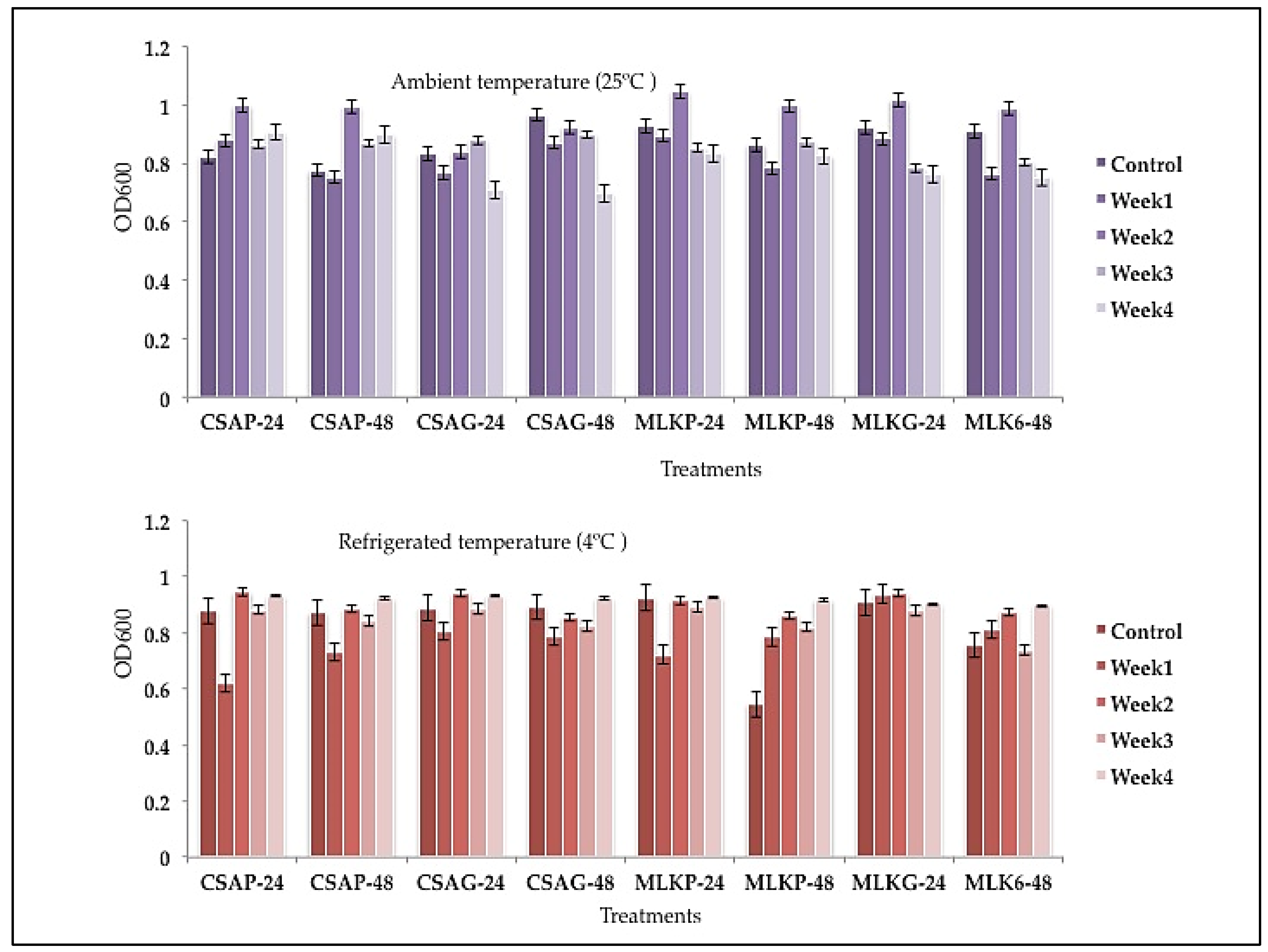

Lactococcus lactis (L3) showed superior survival rates across all the weeks (4) of storage in all the different treatments as it recorded a survival rate of between 53.4% to 76.94% under both storage temperatures. At the end of the fourth week, L3 survived better in skimmed milk using glass as storage container representing 75.45% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25 °C (

Figure 2) at both 24 h and 48 h storage time.

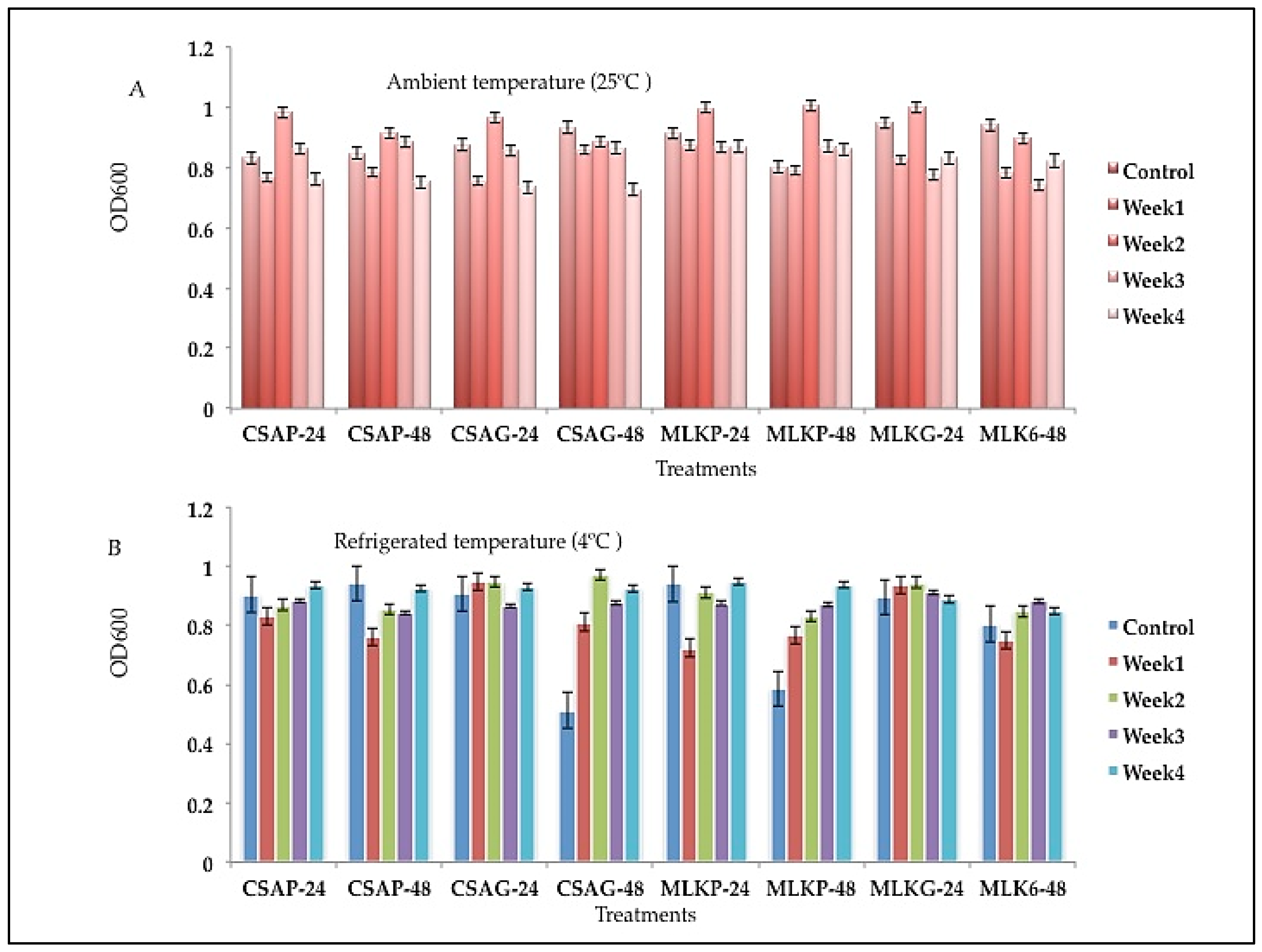

The survival rate of

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) ranges between 62.1% to 89.45% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 3 A&B). L12 survived better in the first week (89.45%) when treated with cassava under plastic storage container, and also survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated in skimmed milk using glass storage container representing 75.97% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25 °C (

Figure 3 A).

The survival rate of

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20), ranges between 60.59% to 89.91% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 3 A&B). However, L20 survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated with cassava using plastic storage container representing 89.91% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25°C and 62.12% survival rate when treated with under glass storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4°C (

Figure 3 A&B).

Viability of combined strains Lactic Acid Bacteria after freeze-drying after.

Combined strains of lactic acid bacteria (Lactococcus

lactis (L3) +

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12),

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20),

Lactobacillus delbruesckii subsp bulgaricus (L12) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) and

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20)) were also freeze-dried in two different kinds of excipients (cassava-CSA and skimmed milk-MLK) and in two different kinds of storage material (Plastic-P and Glass-G) to ascertain which treatment best supports the functionality of the lactic acid bacteria following freeze-drying. Results showed that all the different combined strains survived very well in cassava using plastic as the storage material (CSA_P) with

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Lactobacillus delbruesckii (L12) representing 69.84%,

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) representing 67.3%,

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) representing 68.21% and

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Lactobacillus delbruesckii subsp bulgaricus (L12) +

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) representing 68.19%. However,

Lactococcus lactis (L3) +

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) was able to survive survived better (69.84%) when treated with cassava with plastic as the storage container (A) immediately after freeze-drying (control) (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) immediately after freeze-drying (control).

Viability of combined strains Lactic Acid Bacteria following freeze-drying after weeks of storage.

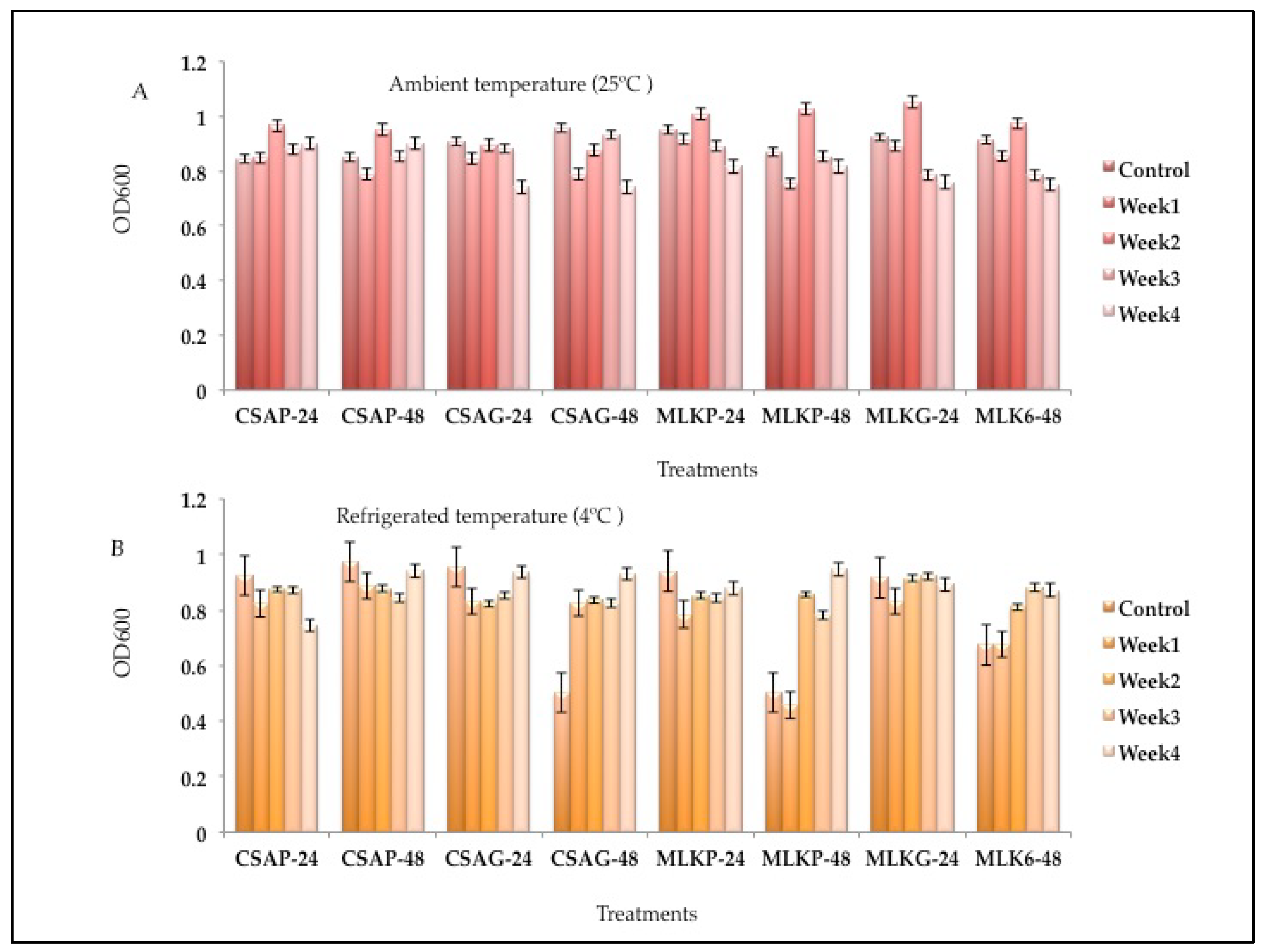

The survival rate of the combined cultures of

Lactococcus lactic (L3)

and Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) ranges between 55.41% to 90.14% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 4 A & B). However, L3 + L12 survived superiorly at the first week when treated with cassava under plastic storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4 °C (90.14%). L3 + L12 survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated in cassava using plastic storage container representing 78.81% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25°C and 61.73% survival rate when treated with skimmed milk under glass storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4 °C (

Figure 4 A & B).

The survival rate of the combined cultures

of Lactococcus lactis (L3) and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20)

, ranges between 57.03% to 78.45% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 5 A and B). L3 + L20 However, survived better at the first week when treated with skimmed milk under plastic storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4°C (78.45%), and also survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated in cassava using glass storage container representing 77.28% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25°C and 63.96% survival rate when treated with skimmed milk under glass storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4°C (

Figure 5 A and B).

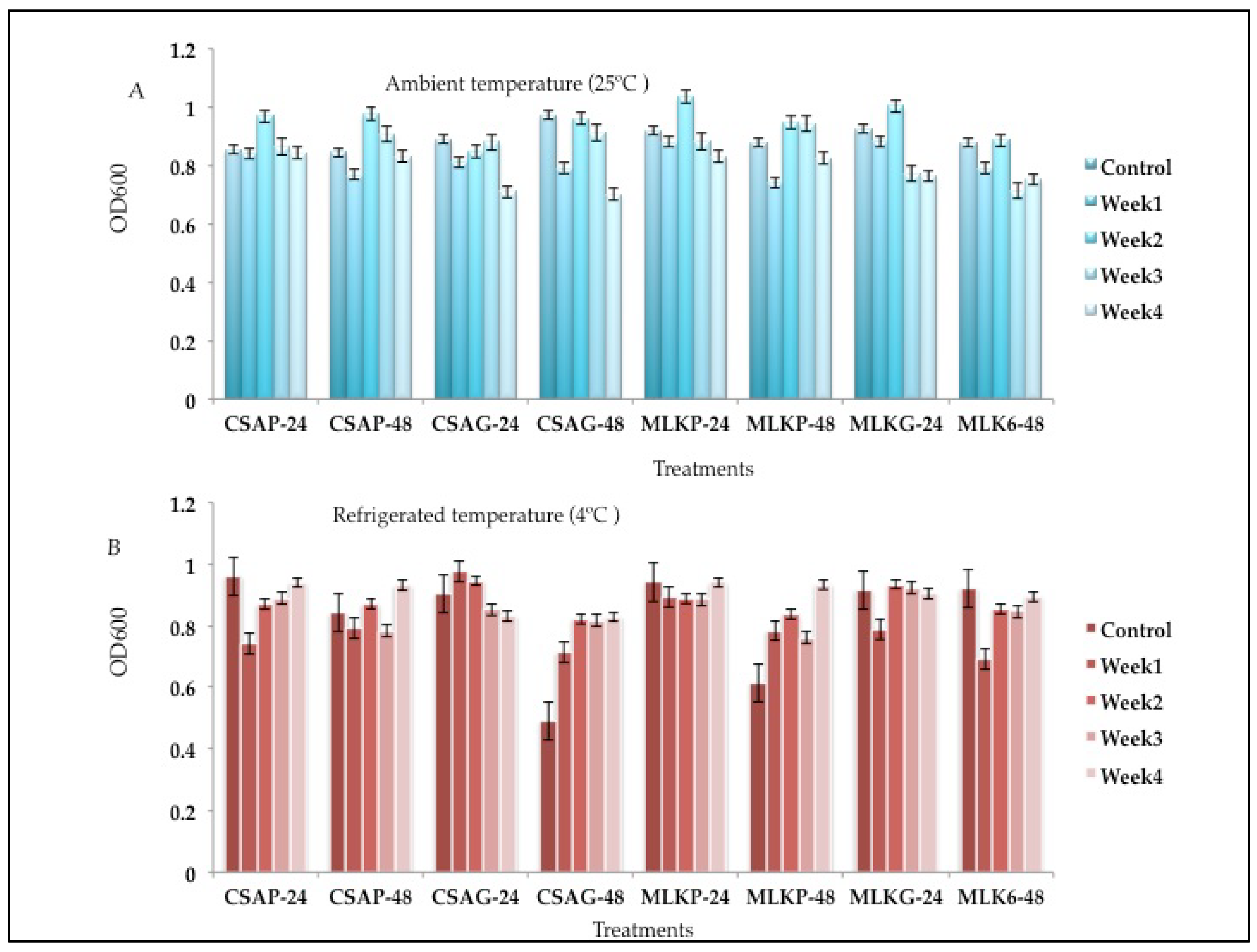

The survival rate of the combined cultures of

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20), ranges between 54.37% to 77.09% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 6 A and B). L12 + L20 However, survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated in cassava using glass storage container representing 77.09% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25°C and 77.30% survival rate when treated with skimmed milk under plastic storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4°C (

Figure 6 A and B).

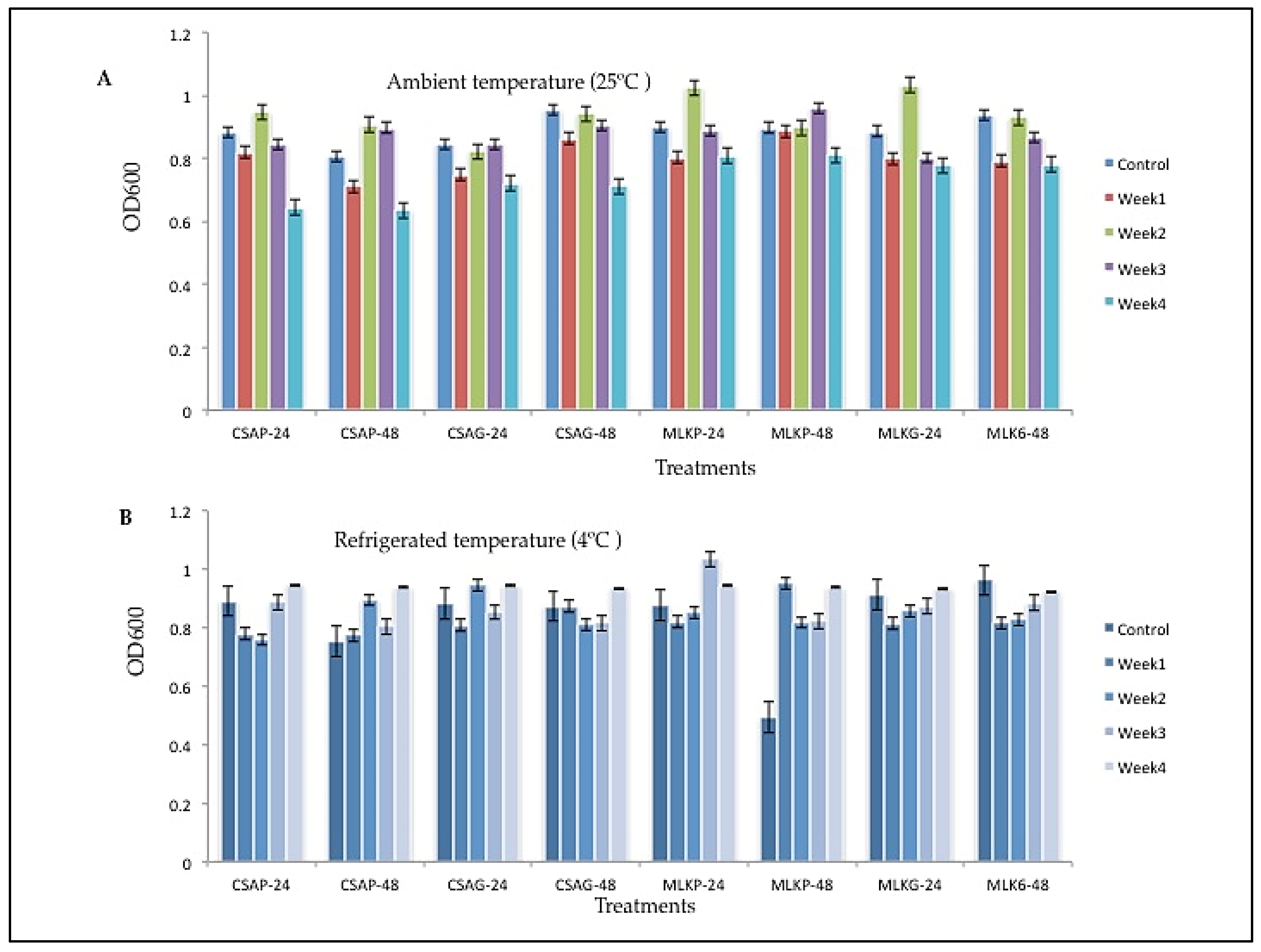

The survival rate of the combined cultures of

Lactococcus lactis (L3), Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) ranges between 52.62% to 81.72% across all the weeks of storage in all the different treatments under both storage temperatures (

Figure 7 A and B). L3 + L12 + L20 However, survived better at the end of the fourth week when treated in cassava using glass storage container representing 81.72% and 70.00% survival rate under ambient storage temperature of 25°C and 70.00% survival rate when treated with skimmed milk under plastic storage container at refrigerated temperature of 4°C (

Figure 7 A and B).

Consumer sensory evaluation of yogurts fermented with freeze-dried starter culture

The effect of freeze-dried LAB cultures on consumer sensory attribute was evaluated using a nine-point hedonic scale with 1, 5, and 9 is presented in

Table 1. The type of starter culture did not have significant effect on colour of yogurt. However, significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed among the different starter culture on yogurt odour, taste, texture, and overall acceptability. The combined starter culture of

Lactococcus lactis (L3) and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12), and a single starter of

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) were highly scored for odour, taste and texture. For overall acceptability, consumers scored yogurts produced with combined starter culture of

Lactococcus lactis (L3) and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12), or single culture of only

Lactococcus lactis as the most preferred products. Except colour where no significant difference was observed, yogurt produced by spontaneous fermentation was least preferred in all other sensory attributes (

Table 2). Also, there was no significant difference between all the strains (single and combined) including yogurt produced from spontaneous fermentation regarding appearance (color). For product odor, taste as well as texture, the combined strains of L3 + L12 is significantly higher as compared to the other strains, except for L3 which showed no significant difference compared to L3 + L12 regarding taste (

P < 0.05). Nonetheless, yogurt produced with a single starter culture of

Lactococcus lactis (L3) or combined starter cultures of

Lactococcus lactis and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L3 + L12) showed significantly higher overall acceptability.

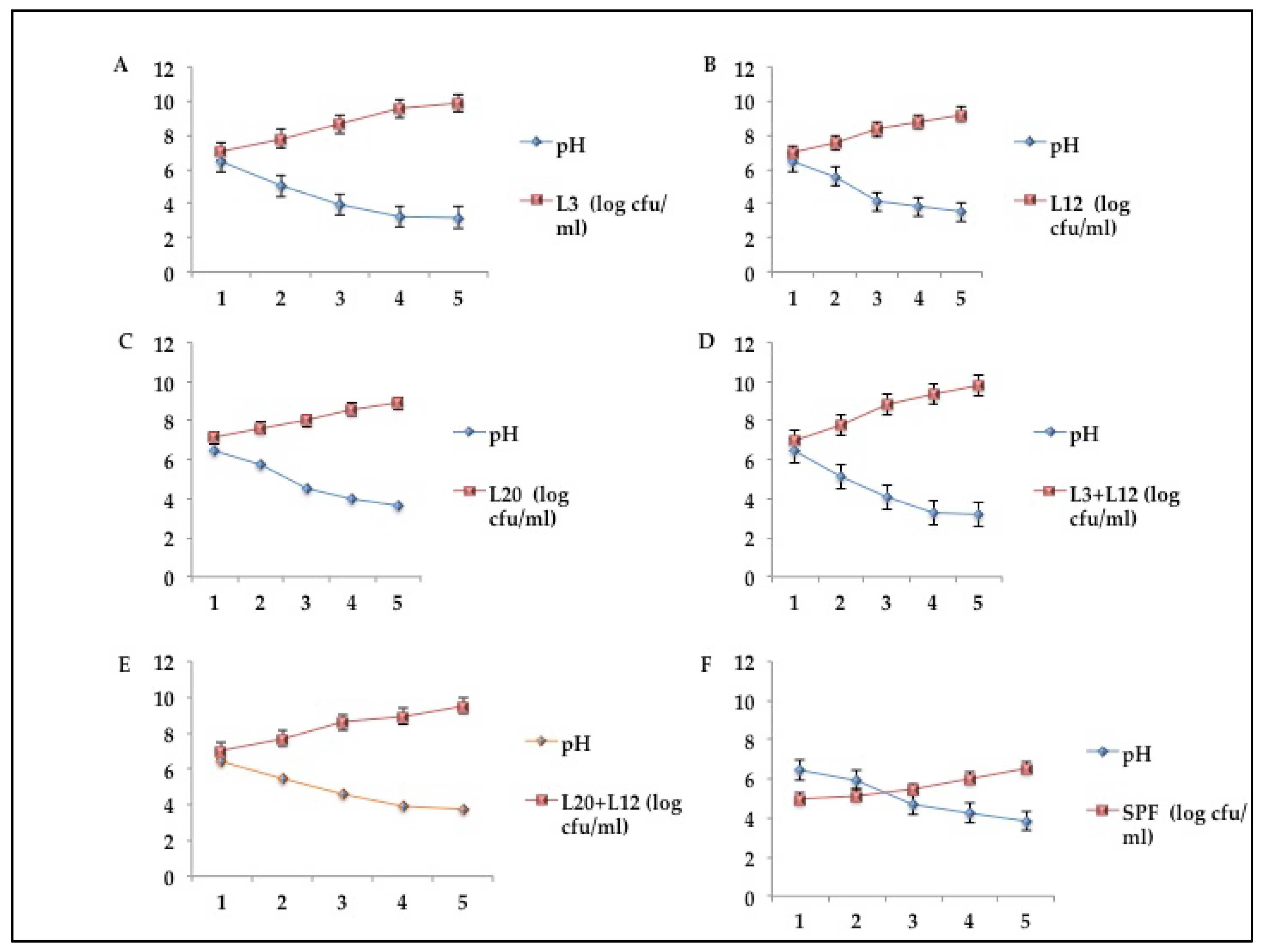

Values represent means of three independent experiments, ±: standard deviation. Values in the same column with different superscript letters are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05). L3: Lactococcus lactis; L12: Lactobacillus delbrueckii; L20: Leuconostoc mesenteroides; L3+L20: combined starter of Lact. lactis and Leuc. mesenteroides; L20+L12: combined starter of Leuc. mesenteroides and Lact. lactis; SPF: spontaneous fermentation (without starter culture).

Discussion

Lactic acid bacteria are predominantly used in the fermentation of milk into fermented milk products, often referred to us yogurt starter cultures or simply starter cultures (Ahmad et al., 2020, Kumar et al 2020, Hwang eta al., 2018, Abesinghe et al., 2019). The purpose of this study was to freeze-dry lactic acid bacteria cultures, determine the (viability) survival rates after freeze-drying and under the influence of different storage materials such as glass and plastic and in different cryoprotectants/buffers/excipients such as skimmed milk and cassava. Also Lactococcus lactis (L3), Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12), and Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) and their combinations, Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp bulgaricus (L12), Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20), Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp bulgaricus (L12) +Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) and Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp bulgaricus (L12) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) were the lactic acid bacteria used for the purpose of this study as they are the most common kind of starter cultures used in yogurt production across Africa (Gu et al., 2021, Celik & Temiz, 2022, Arab et al., 2022, Ghosh 2019).

It was observed in the course of the studies that, the strains performed better under the ambient storage temperature at the fourth week This observation is of immense interest as we are primarily trying to preserve microbial cultures for a longer time period (4 weeks in this study) while minimizing cost in the powdered state. Therefore, the ability of the strains to perform well at ambient condition at the fourth week suggest that within the limits of this study, the strains/cultures would not need refrigeration over 4 weeks’ storage to be use as viable starter cultures. This will reduce to a large extent the cost of maintaining these cultures. Also, transportation of cultures will be less hectic as there will be no need carrying cultures under refrigeration.

Freeze-drying proved to be effective in achieving high survival rates as all the three strains and their combinations achieved >50% survival rates. Microbial preservation by freeze-drying is known to preserve the viability of cultures over long durations (Yao et al. 2008) . Our results agree with those reported by Yao et al. (2009), who found very high survival rates after freeze-drying the strains of L. Plantarum VE36, G2/25 and L. pentosus LB61 with survival rates of 97.3%, 79.9%, and 76.7% respectively. The high survival rate in this study may be attributed to the quality of the sterilization techniques adopted, the efficiency of the freeze-dryer itself and or, the choice of the excipients used (cassava flour and skimmed milk powder) as good excipients can greatly impact survival rates of bacteria survival (Berner and Viernstein 2006). Not all microorganisms can be successfully freeze-dried especially mutants with deficient membranes, several reports have shown lactic acid bacteria been successfully freeze-dried (Yao et al. 2009, Ambros et al., 2018, Fonseca et al., 2021, Enache et al., 2020) with different freeze-drying approaches. This may be due to the removal of the most sensitive parts of the cell population during the freeze-drying process and low surface area of the selected strains. The high survival rates may also be attributed to the rehydration method adopted in this study, as there is an increase in survival rate when the rehydration process is slowed (Carvalho et al. 2004). It may also be due to the high initial cell concentration of the microorganisms, the growth conditions, and the growth media.

Many studies have not been done on the viability of lactic acid bacteria with regards to the influence of storage temperatures, excipients, and storage containers on the bacteria. Our studies showed that all the three strains and their combinations were not affected greatly by the storage containers as well as the storage temperature as all strains survived above 50%. Yao et al. (2009) equally recorded above 50% survival rates of 12 LAB strains out of 16 LAB strains, which they subjected to freeze-drying. The excipients (skimmed milk and cassava flour) were both able to protect the cells from deteriorating and loss of viability. Freeze-dried cultures should be stored in glass containers as very long storage time can cause atmospheric water to diffuse into plastic tubes and damage freeze-dried samples (Bacteria freeze-drying protocol, opsdiagnostics, 2015), even though our studies showed that samples stored in plastic containers showed very good survival rate over the four weeks’ storage duration. Both excipients used in this study supported the viability of the strains. However, strains treated with cassava flour showed superior survival rate over strains treated with skimmed milk as indicated by the results above, this may be due to cassava being a polysaccharide (exopolysaccharide) with some sort of biological essence. Exopolysaccharides have two types of secreted polysaccharides with the first type (capsular polysaccharide) attached to the cell wall as a capsule and the second type (Slime exopolysaccharide) is produced as a loose unattached material.

Exopolysaccharides prevents microbial cells from desiccation, phagocytosis, phage attachment, antibiotics, toxic compounds and osmotic stress (Degeest et al., 2001, Akabanda et al. 2014). Nevertheless, due to the particulate (rough) nature of the reconstituted cassava flour, it was extremely difficult and time-consuming in micro pipetting as observed in this study, even though it was very suitable in terms of cost and durability compared to skimmed milk powder which can easily be contaminated. Skimmed milk is usually selected when it comes to industrial or scale-up or commercial production of freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria. This may be due to several factors such as prevention of cellular injury by stabilizing the cell membrane, creating of a porous structure in the freeze-dried product that makes rehydration easier and finally, it contains proteins that provide a protective coating for the cells (Teixeira and Kirby 1996, Carvalho et al. 2002). This is evident in our study as both excipients led to high survival rates of the LAB strains constituents

Our studies have shown that the bacteria strains used can survive under both ambient (25°C) and refrigerated (4°C) conditions, however, some studies have suggested that freeze-dried samples should be stored in environments with lower temperatures as it impacts survival rates for long storage of samples. In addition to temperature, relative humidity, and exposure to light, all impact survival of freeze-dried samples (Mofidi et al. 2002). Therefore, freeze-dried samples are suggested to be store in a relatively balanced environment, and samples should never be stored in temperatures above 30°C, samples are also suggested to be stored under vacuum and exposed to darkness (Tiradentes et al., 2011).

In the development of starter cultures for the production of fermented milk products, quick acidification is a topmost priority (Yamauchi et al, 2019). The acidification rates varied among the freeze-dried LAB strains tested. Akabanda et al. (2014) reported that Lactobacillus helveticus, L. fermentum, L. plantarum, and L. mesenteroides isolated from nunu were the fastest acid producers in comparison to the other strains used in their study. From the results obtained, all the selected strains tested showed a fast rate of acidification during the period of fermentation. A decrease in pH is essential in yogurt production as it accelerates coagulation and mitigation of pathogenic microflora that might invade the products (Yamauchi et al, 2019, Körzendörfer et al., 2019, Delgado-Fernández et al., 2020). The selected freeze-dried strains are therefore good candidates as starter cultures for the dairy fermentation process. LAB starter cultures that possess the ability to rapidly and completely degrade lactose to lactic acid with minimal nutritional levels are generally desirable. Accelerated acidification of the raw materials means the prevention of the growth and action of undesirable microorganisms on fermented products. This has a positive impact on the aroma, texture, and flavour of the end product. A rapid decrease in pH to <4 indicates the fastest growth and inhibition of starter cultures against pathogenic microbes especially Salmonella spp (Park and Marth 1972).

The purpose of the study was to obtain viable LAB cultures that could be stored for over a long period using freeze-drying preservation technology. Higher colony-forming units indicate high viability and vice versa. Even though the LAB cultures survived fairly well at the end of freeze-drying and following storage over four weeks, the viability still needed to be confirmed by their ability to ferment milk at the end of the fourth week after freeze-drying. Hence, we subjected the LAB to the fermentation of milk (to produce yogurt) for 12 hours measuring cell growth and viability for every 3 hours.

Consumer sensory analysis showed varying degrees of acceptability for yogurt fermented with the different starter cultures Generally, Yogurt fermented with freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria cultures, either single or combined strains, showed improved acceptability as compared to the spontaneously fermented yogurt. The high acceptability of yogurt fermented with Lactococcus lactis (L3) and the combined cultures of Lactococcus lactis and lactobacillus delbrueckii (L3 + L12) could be due to the cultures being able to reduce the pH of the milk from 6.45-3.18 and 6.44-3.20 respectively. Reduction in pH is critical as it affects the organoleptic properties of the yogurt. This may be due to the fact that these cultures were able to produce the lowest pH values (high acidity) during the yogurt fermentation at the end of 12 hours. Park et al. recorded unpleasant acid taste with yogurt acidity more than 1.8% and a titratable acidity about 1.15% considered as the average (Park et al., 2005).

Conclusion

In this study, the potential of the three pre-selected LAB cultures (Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus delbrueckii and Leuconostoc mesenteroides) for use as suitable freeze-dried starter cultures for milk fermentation during yogurt production was assessed. In general, survival rates for lactic acid bacterial cultures ranged between 60.11% and 70.91% following freeze-drying. For single cultures, the highest survival was recorded for Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12), whereas for combined the highest survival was observed for Lactococcus lactis (L3) combined with Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12). The different excipients (cassava and milk) have different varying effects on the different bacterial cultures. All freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria starter cultures whether single or in combinations grew rapidly during yogurt making, reducing the pH of milk to below 4 units within 9 hours of fermentation. On the other hand, spontaneous fermentation (without starter cultures) was characterized by slower acidification. For overall consumer acceptability, yogurts produced with combined starter culture of Lactoccus lactis and Lactobacillus delbrueckii or single culture of Lactococcus lactis were the most preferred products.

Overall, Lactococcus lactis and Lactobacillus delbrueckii can be used as freeze-dried lactic acid bacterial starter culture with high survival rates and high consumer acceptability in the production of yogurt. This can be adopted for large-scale production and commercialization of yogurt production. Notwithstanding, further studies on the effects of freeze-drying and long-term storage on survival and performance of selected LAB cultures are recommended.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding

The study was carried out with funding from Danida through the project: Preserving African Food Microorganisms for Green Growth (DFC No 13-04KU), the United States Department of Education, Title III-HBGI-RES, and National Science Foundation; and HBCU-RISE.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgment

The study was carried out with funding from Danida through the project: Preserving African Food Microorganisms for Green Growth (DFC No 13-04KU).; and HBCU-RISE. We also acknowledge Alabama State University, C-STEM for supplies and Laboratory space. The authors acknowledge receiving funding from United States Department of Education,Title III-HBGI-RES.

References

- Abesinghe, A. M. N. L., Islam, N., Vidanarachchi, J. K., Prakash, S., Silva, K. F. S. T., & Karim, M. A. (2019). Effects of ultrasound on the fermentation profile of fermented milk products incorporated with lactic acid bacteria. International Dairy Journal, 90, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Abi Khalil, R., Yvon, S., Couderc, C., Belahcen, L., Jard, G., Sicard, D., ... & Ayoub, M. J. (2022). Microbial communities and main features of labneh Ambaris, a traditional Lebanese fermented goat milk product. Journal of Dairy Science. [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, R. K., & Narvhus, J. A. (2022). Can ultrasound treatment replace conventional high temperature short time pasteurization of milk? A critical review. International Dairy Journal, 105375. [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O. A. (2020). African sorghum-based fermented foods: past, current and future prospects. Nutrients, 12(4), 1111. [CrossRef]

- Agyei, D., Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Akabanda, F., & Akomea-Frempong, S. (2020). Indigenous African fermented dairy products: Processing technology, microbiology and health benefits. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 60(6), 991-1006. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Banat, F., & Taher, H. (2020). A review on the lactic acid fermentation from low-cost renewable materials: Recent developments and challenges. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 20, 101138. [CrossRef]

- Akabanda Fortune, James Owusu-kwarteng, Kwaku Tano-debrah, Charles Parkouda, and Lene Jespersen. 2014. “The Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria Starter Culture in the Production of Nunu , a Spontaneously Fermented Milk Product in Ghana.” International Journal of Food Science 2014.

- Ambros, S., Mayer, R., Schumann, B., & Kulozik, U. (2018). Microwave-freeze drying of lactic acid bacteria: Influence of process parameters on drying behavior and viability. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 48, 90-98. [CrossRef]

- Arab, M., Yousefi, M., Khanniri, E., Azari, M., Ghasemzadeh-Mohammadi, V., & Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N. (2022). A comprehensive review on yogurt syneresis: effect of processing conditions and added additives. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ayivi, R. D., Gyawali, R., Krastanov, A., Aljaloud, S. O., Worku, M., Tahergorabi, R., ... & Ibrahim, S. A. (2020). Lactic acid bacteria: Food safety and human health applications. Dairy, 1(3), 202-232. [CrossRef]

- Bacteria freeze-drying protocol, opsdiagnostics, 2015 https://opsdiagnostics.com/notes/ranpri/rpbacteriafdprotocol.htm.

- Bircher, Lea, Annelies Geirnaert, Frederik Hammes, Christophe Lacroix, and Clarissa Schwab. 2018. “Effect of Cryopreservation and Lyophilization on Viability and Growth of Strict Anaerobic Human Gut Microbes.” Microbial Biotechnology 11(4):721–733. [CrossRef]

- Brizuela, N. S., Semorile, L. C., Bravo-Ferrada, B. M., & Tymczyszyn, E. E. (2021). Encapsulation of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Sugar Matrices To Be Used as Starters in the Food Industry. In Basic Protocols in Encapsulation of Food Ingredients (pp. 55-61). Humana, New York, NY.

- Carvalho, A. Sofia, Joana Silva, Peter Ho, Paula Teixeira, and F. Xavier Malcata. 2002. “Effect of Additives on Survival of Freeze-Dried Lactobacillus Plantarum and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus during Storage Survival of Freeze-Dried Lactobacillus Plantarum and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus during Storage in the Presence of Protectants.” (October).

- Carvalho, Ana, Paula Teixeira, Paul Gibbs, Ana S. Carvalho, Joana Silva, Peter Ho, Paula Teixeira, F. Xavier Malcata, and Paul Gibbs. 2004. “Relevant Factors for the Preparation of Freeze- Dried Lactic Acid Bacteria . Int Dairy J Relevant Factors for the Preparation of Freeze-Dried Lactic Acid Bacteria.” (October).

- Celik, O. F., & Temiz, H. (2022). Lactobacilli isolates as potential aroma producer starter cultures: Effects on the chemical, physical, microbial, and sensory properties of yogurt. Food Bioscience, 101802. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., & Hang, F. (2019). Lactic acid bacteria starter. In Lactic Acid Bacteria (pp. 93-143). Springer, Singapore.

- de Melo Carvalho, T. (2018). Consistent Scale-Up of The Freeze-Drying Process.

- Degeest, Bart, Frederik Vaningelgem, and Luc De Vuyst. 2001. “Microbial Physiology , Fermentation Kinetics , and Process Engineering of Heteropolysaccharide Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria.” 11:747–57. [CrossRef]

- El-Dein, A. N., Daba, G., Mostafa, F. A., Soliman, T. N., Awad, G. A., & Farid, M. A. (2022). Utilization of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria attaining safety attributes, probiotic properties, and hypocholesterolemic potential in the production of a functional set yogurt. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 43, 102448. [CrossRef]

- Enache, I. M., Vasile, A. M., Enachi, E., Barbu, V., Stănciuc, N., & Vizireanu, C. (2020). Co-microencapsulation of anthocyanins from cornelian cherry fruits and lactic acid bacteria in biopolymeric matrices by freeze-drying: Evidences on functional properties and applications in food. Polymers, 12(4), 906. [CrossRef]

- Estilarte, M. L., Tymczyszyn, E. E., de los Ángeles Serradell, M., & Carasi, P. (2021). Freeze-drying of Enterococcus durans: Effect on their probiotics and biopreservative properties. LWT, 137, 110496. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F., Girardeau, A., & Passot, S. (2021). Freeze-drying of lactic acid bacteria: a stepwise approach for developing a freeze-drying protocol based on physical properties. In Cryopreservation and Freeze-Drying Protocols (pp. 703-719). Humana, New York, NY.

- Fonseca, F., Pénicaud, C., Tymczyszyn, E. E., Gómez-Zavaglia, A., & Passot, S. (2019). Factors influencing the membrane fluidity and the impact on production of lactic acid bacteria starters. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 103(17), 6867-6883. [CrossRef]

- Galli, V., Venturi, M., Mari, E., Guerrini, S., & Granchi, L. (2022). Selection of yeast and lactic acid bacteria strains, isolated from spontaneous raw milk fermentation, for the production of a potential probiotic fermented milk. Fermentation, 8(8), 407. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D. (2019). Comparative study on nutritional profile analysis of herbal yogurt. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 8(5), 174-177.

- Gu, Y., Li, X., Chen, H., Guan, K., Qi, X., Yang, L., & Ma, Y. (2021). Evaluation of FAAs and FFAs in yogurts fermented with different starter cultures during storage. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 96, 103666. [CrossRef]

- Guowei, S., Yang, X., Li, C., Huang, D., Lei, Z., & He, C. (2019). Comprehensive optimization of composite cryoprotectant for Saccharomyces boulardii during freeze-drying and evaluation of its storage stability. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 49(9), 846-857. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C. E., Cho, K. M., Kim, S. C., & Joo, O. S. (2018). Change in physicochemical properties, phytoestrogen content, and antioxidant activity during lactic acid fermentation of soy powder milk obtained from colored small soybean. Korean Journal of Food Preservation, 25(6), 696-705. [CrossRef]

- Jeantet, R., & Jan, G. (2021). Improving the drying of Propionibacterium freudenreichii starter cultures. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 105(9), 3485-3494. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H., Jeong, D., Song, K. Y., & Seo, K. H. (2018). Comparison of traditional and backslopping methods for kefir fermentation based on physicochemical and microbiological characteristics. Lwt, 97, 503-507. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Kaur, A., & Tomer, V. (2020). Process optimization for the development of a synbiotic beverage based on lactic acid fermentation of nutricereals and milk-based beverage. LWT, 131, 109774. [CrossRef]

- Maicas, S. (2020). The role of yeasts in fermentation processes. Microorganisms, 8(8), 1142. [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, Alex, Confluence Engineering Group, Paul A. Rochelle, Connie Chou, and Karl G. Linden. 2002. “Bacterial Survival After Ultraviolet Light Disinfection : Resistance , Regrowth and Repair.” (October).

- Motey, G. A., Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Obiri-Danso, K., Ofori, L. A., Ellis, W. O., & Jespersen, L. (2021). In vitro properties of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria originating from Ghanaian indigenous fermented milk products. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 37(3), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Noguerol, A. T., Igual, M., & Pagán, M. J. (2021). Comparison of biopreservatives obtained from a starter culture of Pediococcus acidilactici by different techniques. Food Bioscience, 42, 101114.

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Akabanda, F., Agyei, D., & Jespersen, L. (2020). Microbial safety of milk production and fermented dairy products in Africa. Microorganisms, 8(5), 752. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Wuni, A., Akabanda, F., & Jespersen, L. (2018). Prevalence and characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes isolates in raw milk, heated milk and nunu, a spontaneously fermented milk beverage, in Ghana. Beverages, 4(2), 40.

- Özel, B., Şimşek, Ö., Settanni, L., & Erten, H. (2020). The influence of backslopping on lactic acid bacteria diversity in tarhana fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 335, 108886. [CrossRef]

- Park, Dong June, Sejong Oh, Kyung Hyung Ku, Chulkyoon Mok, Sae Hun Kim, and Jee Young Imm. 2005. “Characteristics of Yogurt-like Products Prepared from the Combinaton of Skim Milk and Soymilk Containing Saccharified-Rice Solution.” International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 56(1):23–34.

- Sandhya, M., & Disha, K. (2020). Expension in the field of Freeze-drying: An Advanced Review. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 13(5), 2468-2474. [CrossRef]

- Sessou, P., Keisam, S., Tuikhar, N., Gagara, M., Farougou, S., & Jeyaram, K. (2019). High-Throughput Illumina MiSeq amplicon sequencing of yeast communities associated with indigenous dairy products from republics of benin and niger. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 594. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Paula and Roy Kirby. 1996. “Changes in the Membrane of Lactobacillus Bulgaricus during Storage Following Freeze-Drying Changes in the Cell Membrane of Lactobacillus Bulgaricus Storage Following Freeze-Drying.” (October).

- Terpou, A., Papadaki, A., Lappa, I. K., Kachrimanidou, V., Bosnea, L. A., & Kopsahelis, N. (2019). Probiotics in food systems: Significance and emerging strategies towards improved viability and delivery of enhanced beneficial value. Nutrients, 11(7), 1591. [CrossRef]

- Tiradentes, Universidade, Giovana Verginia Barancelli, and Carmen J. Contreras-castillo. 2011. “Microbial Deterioration of Vacuum-Packaged Chilled Beef Cuts and Techniques for Microbiota Detection and Characterization : A Review.” (March). [CrossRef]

- Venema, K., & Surono, I. S. (2019). Microbiota composition of dadih–a traditional fermented buffalo milk of West Sumatra. Letters in applied microbiology, 68(3), 234-240. [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G., Champagne, C. P., & Desfossés-Foucault, É. (2019). The production of lactic acid bacteria starters and probiotic cultures: An industrial perspective. In Lactic Acid Bacteria (pp. 317-336). CRC Press.

- Voidarou, C., Antoniadou, M., Rozos, G., Tzora, A., Skoufos, I., Varzakas, T., ... & Bezirtzoglou, E. (2020). Fermentative foods: Microbiology, biochemistry, potential human health benefits and public health issues. Foods, 10(1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., He, L., An, W., Yu, D., Liu, S., & Shi, K. (2019). Lyoprotective effect of soluble extracellular polymeric substances from Oenococcus oeni during its freeze-drying process. Process Biochemistry, 84, 205-212. [CrossRef]

- Wirawati, C. U., Sudarwanto, M. B., Lukman, D. W., Wientarsih, I., & Srihanto, E. A. (2019). Diversity of lactic acid bacteria in dadih produced by either back-slopping or spontaneous fermentation from two different regions of West Sumatra, Indonesia. Veterinary World, 12(6), 823. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, R., Maguin, E., Horiuchi, H., Hosokawa, M., & Sasaki, Y. (2019). The critical role of urease in yogurt fermentation with various combinations of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus. Journal of dairy science, 102(2), 1033-1043. [CrossRef]

- Yao, A. A., F. Bera, C. Franz, and W. Holzapfel. 2008. “Survival Rate Analysis of Freeze-Dried Lactic Acid Bacteria Using the Arrhenius and z -Value Models.” Journal of Food Protection 71(2):431–34. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Amenan a, Carine Dortu, Moutairou Egounlety, Cristina Pinto, Vinodh a Edward, Melanie Huch, Charles M. a P. Franz, Willhelm Holzapfel, Samuel Mbugua, Moses Mengu, and Philippe Thonart. 2009. “Production of Freeze-Dried Lactic Acid Bacteria Starter Culture for Cassava Fermentation into Gari.” African Journal of Biotechnology 8(19):4996–5004.

- Zang, J., Xu, Y., Xia, W., & Regenstein, J. M. (2020). Quality, functionality, and microbiology of fermented fish: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 60(7), 1228-1242.

Figure 1.

Study design; Each Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria: Lactococcus lactis (L3), L. delbrueckii (L12), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20), and their combinations (L3 + L12, L3 + L20, L12 + L20, L3 + L12 + L20) goes through these treatments.

Figure 1.

Study design; Each Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria: Lactococcus lactis (L3), L. delbrueckii (L12), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20), and their combinations (L3 + L12, L3 + L20, L12 + L20, L3 + L12 + L20) goes through these treatments.

Figure 2.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 2.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 3.

Viability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 3.

Viability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 4.

Viability of Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 4.

Viability of Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 5.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 5.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 6.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25 °C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4 °C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 6.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25 °C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4 °C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 7.

Viability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 7.

Viability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 8.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4 °C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 8.

Viability of Lactococcus lactis (L3) + Lactobacillus delbrueckii (L12) + Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L20) following freeze-drying, stored at A) Ambient temperature (25°C), and B) Refrigerated temperature (4 °C) for 24 h and 48 h. CSAP-24-Cassava in plastic at 24 h, CSAP-48-Cassava in plastic at 48 h, CSAG-24-Cassava in glass at 24 h, CSAG-48-Cassava in glass at 48 h, MLKp-24-Milk in plastic at 24 h, MLKP-48-Milk in plastic at 48 h, MLKG-24-Milk in glass at 24 h, MLKG-48-Milk in glass at 48 h. (Values represent means of three replicate experiments, ±: standard deviation).

Figure 9.

LAB count (log cfu/ml) and pH of yogurt produced from freeze-dried starter cultures.

Figure 9.

LAB count (log cfu/ml) and pH of yogurt produced from freeze-dried starter cultures.

Table 1.

Single and combined freeze-dried starter cultures on fermentation.

Table 1.

Single and combined freeze-dried starter cultures on fermentation.

| Fermentation |

Starter culture |

Codes of starter culture |

| Single starter culture |

Lactococcus lactis |

L3 |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus |

L12 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides |

L20 |

| Combined starter cultures |

Lactococcus lactis + L. delbrueckii |

L3+L12 |

|

Leuconostoc mesenteroides + L. delbrueckii |

L20+L12 |

| Spontaneous fermentation (control) |

No starter added |

SPF |

Table 2.

Consumer sensory evaluation of traditional yogurts produced with freeze-dried starter cultures.

Table 2.

Consumer sensory evaluation of traditional yogurts produced with freeze-dried starter cultures.

| Starter culture |

Sensory attribute |

| Colour |

Odour |

Taste |

Texture |

Overall acceptability |

| L3 |

8.04 ± 1.35a

|

7.16 ± 1.21a

|

7.23 ± 1.30a

|

7.72 ± 1.52a

|

8.36 ± 1.18a

|

| L12 |

7.95 ± 1.40a

|

7.01 ± 1.19a

|

6.65 ± 1.25b

|

7.60 ± 1.45a

|

7.22 ± 1.15b

|

| L20 |

8.00 ± 1.20a

|

8.37 ± 1.25b

|

7.14 ± 1.30ac

|

7.84 ± 1.33ab

|

7.39 ± 1.50b

|

| L3+L12 |

8.06 ± 0.95a

|

8.83 ± 1.10b

|

7.37 ± 1.05a

|

8.08 ± 0.96b

|

8.45 ± 0.99a

|

| L20+L12 |

7.90 ± 1.15a

|

7.20 ± 1.21a

|

6.91 ± 1.27c

|

7.75 ± 1.65a

|

7.30 ± 1.05b

|

| SPF |

7.96 ± 1.20a

|

6.03 ± 0.83c

|

6.20 ± 1.24d

|

7.02 ± 0.73c

|

6.25 ± 1.00c

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).