Submitted:

11 January 2023

Posted:

16 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

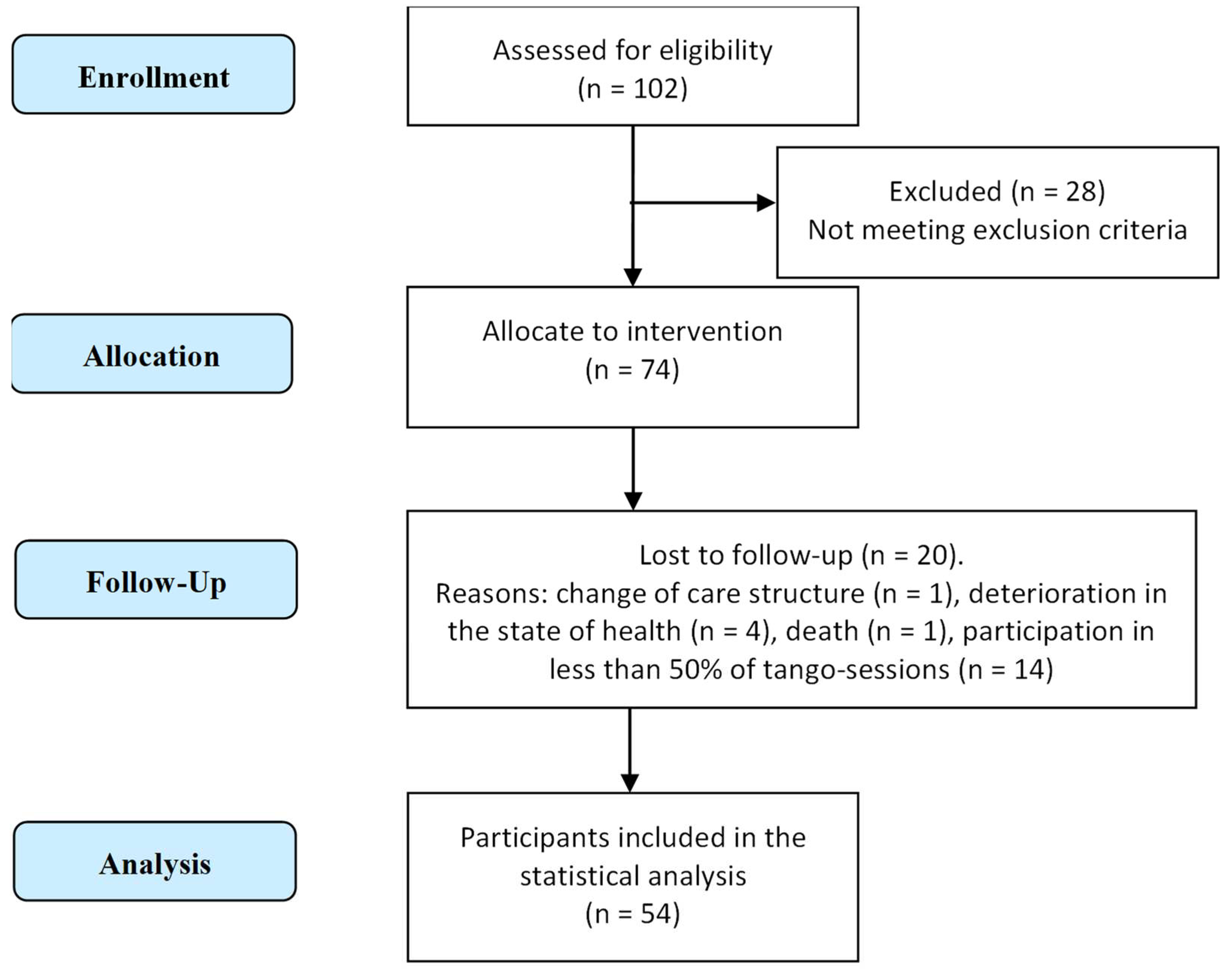

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

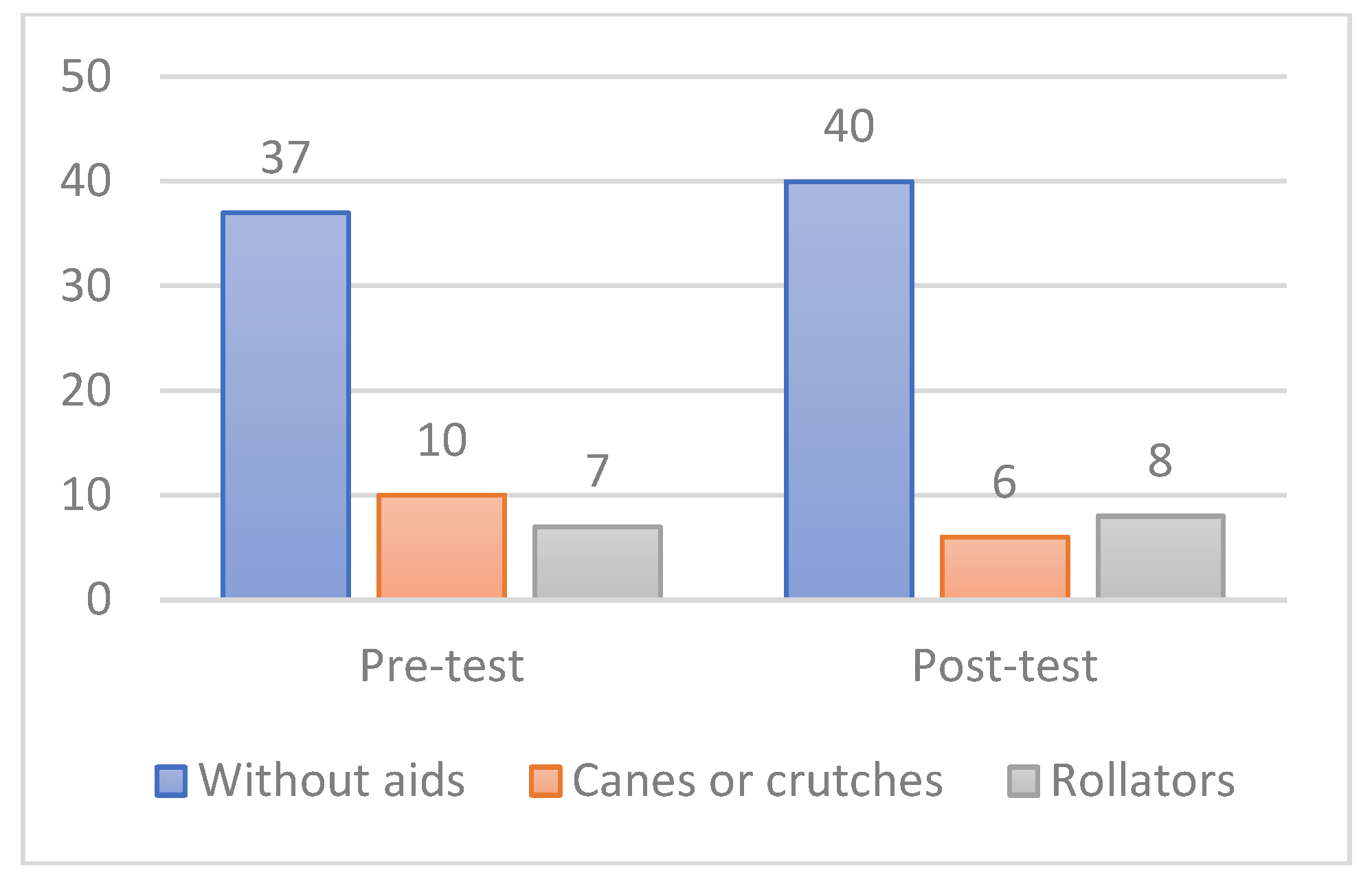

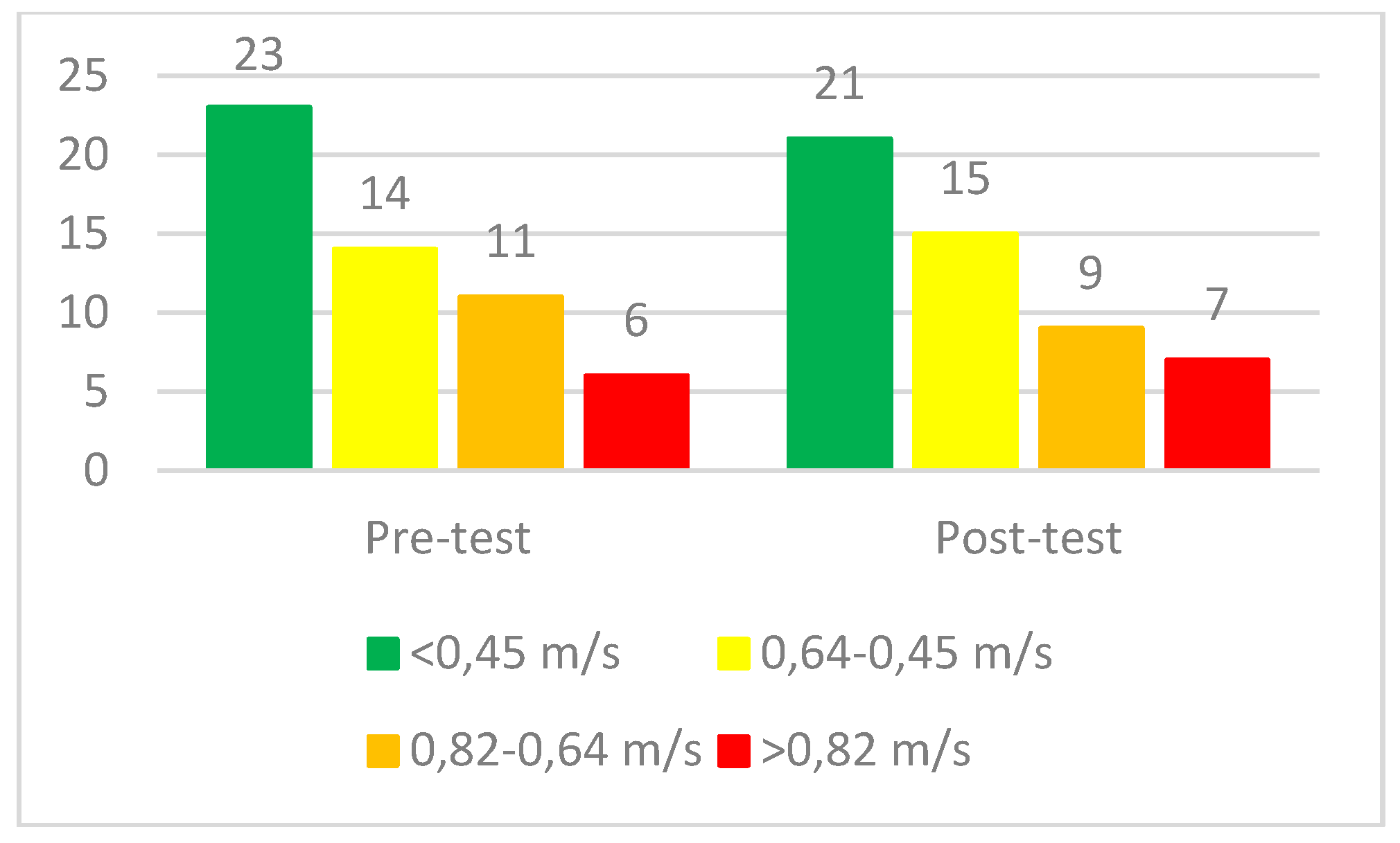

3.1. Sample Characteristic

3.2. Feasibility

3.3. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, M.E.; Close, J.C.T. Dementia. In; 2018; pp. 303–321 ISBN 9780444639165.

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Fusco, D.; Mastropaolo, S.; Quattrociocchi, D.; Proia, A.; Russo, A.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sarcopenia Among Nursing Home Older Residents. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67A, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Colaço Harmand, M.; Meillon, C.; Rullier, L.; Avila-Funes, J.A.; Bergua, V.; Dartigues, J.F.; Amieva, H. Cognitive Decline after Entering a Nursing Home: A 22-Year Follow-up Study of Institutionalized and Noninstitutionalized Elderly People. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Medeiros, M.M.D.; Carletti, T.M.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Rodrigues-Garcia, R.C.M. Does the Institutionalization Influence Elderly’s Quality of Life? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkers, K.M.; Scherder, E.J.A. Impoverished Environment, Cognition, Aging and Dementia. revneuro 2011, 22, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picanço-Diniz, C.; Galdino De Oliveira, T.C.; Cabral Soares, F.; Dias E Dias De Macedo, L.; Wanderley Picanco Diniz, D.L.; Valim Oliver Bento-Torres, N. Beneficial Effects of Multisensory and Cognitive Stimulation on Age-Related Cognitive Decline in Long-Term-Care Institutions. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manckoundia, P.; Mourey, F.; Pfitzenmeyer, P. Marche et Démences. Ann. Réadaptation Médecine Phys. 2008, 51, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiepe, M.-S.; Stöckigt, B.; Keil, T. Effects of Dance Therapy and Ballroom Dances on Physical and Mental Illnesses: A Systematic Review. Arts Psychother. 2012, 39, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellotti, A.M.; Stevenson, R.; Doumas, M. The Efficacy of Dance for Improving Motor Impairments, Non-Motor Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0236820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.K.; Wong, J.S.; Prout, E.C.; Brooks, D. Dance for the Rehabilitation of Balance and Gait in Adults with Neurological Conditions Other than Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell-Miller, H.; Hughes, P.; Westacott, M.; Odell-Miller, H.; Hughes, P.; Westacott, M. An Investigation into the Effectiveness of the Arts Therapies for Adults with Continuing Mental Health Problems. Psychother. Res. 2006, 16, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.C.; Mergheim, K.; Raeke, J.; Machado, C.B.; Riegner, E.; Nolden, J.; Diermayr, G.; von Moreau, D.; Hillecke, T.K. The Embodied Self in Parkinson’s Disease: Feasibility of a Single Tango Intervention for Assessing Changes in Psychological Health Outcomes and Aesthetic Experience. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein-Levitas, N. Dance/Movement Therapy and Sensory Stimulation: A Holistic Approach to Dementia Care. Am. J. Danc. Ther. 2016, 38, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Byers, C.; Butler, G.; Sweeney, M.; Rossbach, L.; Bozzorg, A. Adapted Tango Improves Mobility, Motor–Cognitive Function, and Gait but Not Cognition in Older Adults in Independent Living. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, K.E.; Hackney, M.E. The Effects of Adapted Tango on Spatial Cognition and Disease Severity in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Mot. Behav. 2013, 45, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lötzke, D.; Ostermann, T.; Büssing, A. Argentine Tango in Parkinson Disease – a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, F. Tango, Corps à Corps Culturel : Danser En Tandem Pour Mieux Vivre; Presses de l’Université de Quebec, Ed.; Collection Santé et Societé: Québec, 2009; ISBN 978-2-7605-2392-0.

- Peidro, R.M.; Osses, J.; Caneva, J.; Briont, G.; Angelino, A.; Kerbage, S.; Garcia Ben, M.; Pesce, R. Tango: Modificaciones Cardiorrespiratorias Durante El Baile. Rev. Argent. Cardiol. 2002, 70, 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, Y.; Hur, Y.; Noh, G. Tango Posture and Stance: Functional Anatomical Analysis and Therapeutic Characteristics. J. Tango 2019, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.; Hur, Y.; Kim, I.S.; Ha, C.W.; Noh, G. Tango Gait for Tango Therapy: Functional Anatomical Characteristics of Tango Gait (‘Tango Gaitology’). J. Tango 2019, 1, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.; Kim, I.C.S.; Noh, G. Tango Therapy: Current Status and the Next Perspective. J. Clin. Rev. Case Reports 2018, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, P.; Jacobson, A.; Leroux, A.; Bednarczyk, V.; Rossignol, M.; Fung, J. Effect of a Community-Based Argentine Tango Dance Program on Functional Balance and Confidence in Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2008, 16, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-García, A.; Hughes, J.C.; James, I.A.; Rochester, L.; Guzman-Garcia, A.; Hughes, J.C.; James, I.A.; Rochester, L. Dancing as a Psychosocial Intervention in Care Homes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, Y.S.; Slade, S.C.; Tamplin, J.; Wittwer, J.E.; Gray, R.; Blackberry, I.; Morris, M.E. Therapeutic Dancing for Frail Older People in Residential Aged Care: A Thematic Analysis of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 90, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracco, L.; Poirier, G.; Pinto-Carral, A.; Mourey, F. Effect of Dance Therapy on the Physical Abilities of Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2021, 3, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delphin-Combe, F.; Dauphinot, V.; Denormandie, P.; Sanchez, S.; Hay, P.-E.; Moutet, C.; Krolak-Salmon, P. The Scale of Instantaneous Wellbeing: Validity in a Population with Major Neurocognitive Disorders. Gériatrie Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. du Viellissement 2018, 16, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treacy, D.; Hassett, L. The Short Physical Performance Battery. J. Physiother. 2018, 64, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Staff of The Benjamin Rose Hospital Multidisciplinary Study of Illness in Aged Persons. I. Methods and Preliminary Results. J. Chronic Dis. 1958, 7, 332–345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousi, C.; Igier, V.; Quintard, B. French Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease Scale in Nursing Homes (QOL-AD NH). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Caoimh, R.; O’Donovan, M.R.; Monahan, M.P.; Dalton O’Connor, C.; Buckley, C.; Kilty, C.; Fitzgerald, S.; Hartigan, I.; Cornally, N. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 Nursing Home Restrictions on Visitors of Residents With Cognitive Impairment: A Cross-Sectional Study as Part of the Engaging Remotely in Care (ERiC) Project. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logsdon, R.G.; Gibbons, L.E.; McCurry, S.M.; Teri, L. Assessing Quality of Life in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Sala, J.L.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Turró-Garriga, O.; López-Pousa, S.; Vilalta-Franch, J. Factors Related to Perceived Quality of Life in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: The Patient’s Perception Compared with That of Caregivers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gallego, M.; Gómez-Amor, J.; Gómez-García, J. Determinants of Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease: Perspective of Patients, Informal Caregivers, and Professional Caregivers. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2012, 24, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud Mermoud, V.; Morin, D. Regards Croisés Entre l’évaluation de La Qualité de Vie Perçue Par Le Résident Hébergé En Établissement Médico-Social et Par Le Soignant Référent. Rech. Soins Infirm. 2016, 126, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, D.; Hedley, L.; Milverton, R. Exploring Dance as a Therapy for Symptoms and Social Interaction in a Dementia Care Unit. Nurs. Times 2009, 105, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sjögren, K.; Lindkvist, M.; Sandman, P.-O.; Zingmark, K.; Edvardsson, D. To What Extent Is the Work Environment of Staff Related to Person-Centred Care? A Cross-Sectional Study of Residential Aged Care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brami, C.; Trivalle, C.; Maillot, P. Feasibility and Interest of Exergame Training for Alzheimer Patients in Long-Term Care [Faisabilité et Intérêt de l’entraînement En Exergames Pour Des Patients Alzheimer En SLD]. NPG Neurol. - Psychiatr. - Geriatr. 2018, 18, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charras, K.; Mabire, J.-B.; Bouaziz, N.; Deschamps, P.; Froget, B.; de Malherbe, A.; Rosa, S.; Aquino, J.-P. Dance Intervention for People with Dementia: Lessons Learned from a Small-Sample Crossover Explorative Study. Arts Psychother. 2020, 70, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Earhart, G.M. Recommendations for Implementing Tango Classes for Persons with Parkinson Disease. Phys. Ther. Fac. Publ. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Inappropriate Behaviors in Dementia: A Review, Summary, and Critique. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001, 9, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Shea, E.O.; Cooney, A. Quality of Life for Older People Living in Long-Stay Settings in Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, M.; Khibri, H.; Harmouche, H.; Ammouri, W.; Tazi-Mezalek, Z.; Adnaoui, M. Impact Du Confinement Sur La Santé Des Personnes Âgées Durant La Pandémie COVID-19. NPG Neurol. - Psychiatr. - Gériatrie 2020, 20, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Díaz de Bustamante, M.; Aparicio Mollá, S.; Arenas, M.C.; Jiménez-Armero, S.; Lacosta Esclapez, P.; González-Espinoza, L.; Bermejo Boixareu, C. Functional, Cognitive, and Nutritional Decline in 435 Elderly Nursing Home Residents after the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokkanen, L.; Rantala, L.; Remes, A.M.; Harkonen, B.; Viramo, P.; Winblad, I. Dance/Movement Therapeutic Methods in Management of Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 771–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machacova, K.; Vankova, H.; Volicer, L.; Veleta, P.; Holmerova, I. Dance as Prevention of Late Life Functional Decline Among Nursing Home Residents. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 1453–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanesi, C.; DeSouza, J.F.X. Beauty That Moves: Dance for Parkinson’s Effects on Affect, Self-Efficacy, Gait Symmetry, and Dual Task Performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios Romenets, S.; Anang, J.; Fereshtehnejad, S.-M.; Pelletier, A.; Postuma, R. Tango for Treatment of Motor and Non-Motor Manifestations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Control Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, K.; Cauda, F.; Cerliani, L.; Mate, D.; Duca, S.; Geminiani, G.C. Motor Imagery of Walking Following Training in Locomotor Attention. The Effect of ‘the Tango Lesson’. Neuroimage 2006, 32, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkou, V.; Meekums, B. Dance Movement Therapy for Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD011022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabire, J.-B.; Aquino, J.-P.; Charras, K. Dance Interventions for People with Dementia: Systematic Review and Practice Recommendations. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 31, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.; Longhurst, S.; Higginson, I.J. Challenges to Conducting Research with Older People Living in Nursing Homes. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, L.; Miller, D.K.; McGloin, J.M.; Freeman, M.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Magaziner, J.; Studenski, S. Recruitment and Retention of Older Adults in Aging Research. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studenski, S. Challenges in Clinical Aging Research: Building the Evidence Base for Care of the Older Adult. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 2351–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Session Components | Activities |

|---|---|

| Pre-warm-up | Organizing the seating arrangement in the room, greeting the participants, engaging in small talk |

| Warm-up | Seated exercises to mobilize lower and upper limbs, head and trunk as well as singing to warm-up the voice and foster social connection |

| Main part | Different aspects of tango therapy were practiced. This could include technical aspects such as: foreword and backward walking, side-step, square, rectangle, as well as improvisation via spontaneous expression. The physical connection via ‘Abrazo’ (embrace) or other interactions were also an important aspect of the intervention. |

| Cool-down | Seated rituals such as singing and breathing exercises. |

| Social exchange | The sessions were frequently followed by coffee and cake, or participants still stayed around to talk with each other and facilitators. |

| Song title | Artist |

|---|---|

| Le plus beau tango du monde | Tino Rossi |

| Paloma | Tino Rossi |

| Mon Amant de Saint Jean | Lucienne Delyle |

| Voulez-Vous Danser Grand'mère | Lina Margy |

| Vous Permettez Monsieur | Salvatore Adamo |

| Variables | Total (N=54) |

|---|---|

| Sex, females, n (%) | 42 (78) |

| Age (years), M ± SD | 84.9 ± 6.7 |

| Charlson Index, M ± SD | 5.6 ± 1.6 |

| MMSE, score (range 0–30) M ± SD | 14.5 ± 7.4 |

| Katz Index, score (range 0–6) M ± SD | 4.5 ± 1.3 |

| Variables | Pre-test M ± SD | Post-test M ± SD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPPB | Balance subscore (0-4) | 2,1 ± 0,9 | 2,3 ± 1 | 0,221 |

| Gait speed subscore (0-4) | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1,1 | 0,725 | |

| Sit to stand subscore (0-4) | 1,2 ± 1,2 | 1,2 ± 1,2 | 0,862 | |

| Total score (0-12 | 5,3 ± 2,4 | 5,4 ± 2,6 | 0,876 | |

| Katz Index, score (range 0–6) M ± SD | 4,5 ± 1,3 | 4,3 ± 1,2 | 0,253 | |

| QoL-AD, score (range 13–52) | Participant | 33,8 ± 5,4 | 34,3 ± 5,7 | 0,172 |

| Caregiver | 31,9 ± 4,5 | 33 ± 4,2 | 0,103 | |

| Weighted composite score | 33,1 ± 4,6 | 34 ± 4,5 | 0,030* | |

| 1 | To know more: http://www.abbreportages.fr/content/view/214/186/lang,english/ |

| 2 | To know more: https://sefca.u-bourgogne.fr/toute-lactualite/379-la-melodie-d-alzheimer.html?fbclid=IwAR0bu8hkfWfMJ39oRRZNGcI9aFG-HK4CTy9YucKr72Quwvb04P4ivC4TkEE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).