1. Introduction

Hepatitis B viral infection (HBV) is a deadly blood borne vaccine preventable liver disease affecting more than two billion people worldwide [

1]. It is the top cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (3, 5). Globally, the prevalence of HBV infections estimated to be around 1.3% with rates ranging from as low as 0.2 % in America to as high as 8% in Africa [

4]. In Tanzania, the prevalence of HBV was reported to be ranging from 5.5- 20% in the general population [

5].

Health care workers (HCWs) are four times likely to acquire HBV infection than the general population. This is due to the fact that they encounter many occupational risk exposures like needle stick injuries as well as body fluid splashes among others [

6,

7]. According to Global policy report on the prevention and control of viral hepatitis among WHO member states, about two million HCW are at risk of being infected with HBV each year in a midlist of low vaccination coverage [

3]. Recent meta-analysis study conducted in Africa and Asia reported the prevalence of HBV among HCWs to be ranging from 4.0 to 5.0 in Asia and Africa respectively [

8]. In Tanzania the prevalence of HBV infection among HCWs is even higher ranging from 5.7% to 7% [

9,

10].

In order to prevent HBV infection among HCW various interventions have been recommended. These include but not limited to observing infection control strategies, blood safety through screening before transfusion as well as vaccination. Of these, the latter is the most cost-effective intervention as it conveys a protective efficacy of more than ninety percent [

11]. Despite the availability of HBV vaccine only one out of five HCWs in tertiary referral hospitals had a protective immunity resulted from active vaccination [

9]. The uptake of HBV vaccine and the associated factors among HCWs in primary health facilities remains not widely studied in Tanzania. This study therefore aimed at determining the extent to which HCWs in primary health facilities are vaccinated against HBV and the associated factors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area, design and participants

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Misungwi and Ilemela districts both located in Mwanza Region. A total of 339 and 473 HCW were proving health services in primary health facilities in Ilemela and Misungwi respectively. The former district is located in urban area whereas the last-mentioned is in rural setting (63). There are 14 Dispensaries in Ilemela district and 4 public health centers whereas Misungwi district has a total of 43 dispensaries and 4 Health centers.

2.2. Sample size estimation and sampling techniques

Sample size was calculated by using Taro Yamane formula [

12] to give a minimum sample size required. The obtained sample size was multiplied by 1.5 in order to cover for design effect and subsequently the sample size of 402 participants was reached. The two study areas were purposefully selected to represent rural and urban settings. For the purpose of ensuring representativeness, approximately one-third of all primary health facilities from each district were randomly selected. All HCWs from the respectively sampled health facilities participated in the study.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

The study participants were HCW working at the selected primary health facilities and had served in that particular facility for more than one year.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

HCW born after 2002 were excluded from the study as they are more likely to have been vaccinated by the national expanded program for immunization.

2.4. Data collection, tools and procedures

A pre-tested semi- structured self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire had a total of seven sections. The sections included socio-demographic information of participants, exposure status to HBV and its risk factors, awareness of HBV, knowledge of participants on HBV, HBV vaccination status and their perception toward HBV and vaccine. Awareness was measure using a single question that required a participant to answer whether they had heard of HBV before or not. Knowledge assessment was done by adapting a work from Abdul Hakeem et [

13]. In this section a total of ten questions on HBV transmission, prevention and treatment were asked to a participant in order to have a clue on their understanding of the disease. HBV vaccine uptake was determined by a section in the questionnaire where the participants were asked whether they have been vaccinated or not. Then they were asked on the number of HBV vaccine shots they had received. Participants who had received a total of three shots were regarded as vaccinated and those who had received less than three shots or none were considered not vaccinated. Perception on HBV vaccine and infection was measured using the six constructs of the health belief model namely perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived self-efficacy, perceived barriers and cues to action, where each of the constructs had a number of statement [

14]. The statements were in form of questions with a minimum of two statements on the construct.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were entered into excel® sheet and then exported to IBM SPSS® version 25 for analysis. The continuous variables were summarized as mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range depending on the distribution. The categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions. For the identification of factors associated with uptake of HBV vaccination, bivariate logistic regression was done for each independent variable. Variables with p-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis was performed using multivariate logistic regression model for all variables with p-values ≤0.2 during the bivariate analysis.

Knowledge assessment was measured using the following questions on the knowledge section of the questionnaire. How is HBV transmitted?, Is HBV a preventable disease?, What can be done to prevent HBV infection?, If a person is found HBV positive what will be done in Tanzania?, Is HBV DNA recombinant vaccine capable of protecting a vaccinated person against HBV infection?, Who is at risk of being infected with HBV?, Is HBV vaccine available in Tanzania?, What is the minimum number of HBV shot needed to protect against HBV?, Is it important to conduct an immune response test after HBV vaccine?, What is to be done after being accidentally contacted with HBV infected person blood or body fluid products? and What is the route of HBV recombinant vaccine?. Each correct response was scored one mark while the wrong response and I don’t know response scored zero. The total scores for each participant was obtained and converted into percentages and categorized as poor knowledge category was for the score of <50%, fair 50-74% and good knowledge >75% [

13].

Perception of PrEP was categorized as high perception and low perception. The variables were recoded into different variables and for each of the constructs of the health belief model a set of questions were asked with the response options of agree, not sure, and disagree. These were subsequently given a score of 3, 2, and 1 point, respectively. Participants with a score above the median on each construct of the health belief model were considered to have a high perception toward PrEP and those with a score below or equal to the median were considered to have low perception.

3.Results

3.1.Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

This study sampled 402 HCWs from 27 health facilities from Misungwi and Ilemela districts. The mean age of the participants was 34.9 ±7.7 years (95% CI, 34.1-35.1) and the majority were females (56.5% (227/402). A total of 217 (54%) HCW were recruited from Misungwi and the rest from Ilemela district. Nurses were the majority (36.8% (148/402) of all medical cadres participated in the study. Further details on the above descriptions are tabulated below (

Table 1).

3.2. Risk exposures of HBV infection among HCWs in Misungwi and Ilemela districts

Nearly half (46.3% (186/402) of the participants reported to have tested for HBV infection they all reported a negative status. Additionally, a total of 188 (46.8%) HCWs reported to have been exposed to needle prick injury in the past year before the study. On the other hand, 90.3% of all study participants used protective gears when attending their clients.

Table 2 shows hepatitis B risky exposures and protective behavior assessment among the study participants.

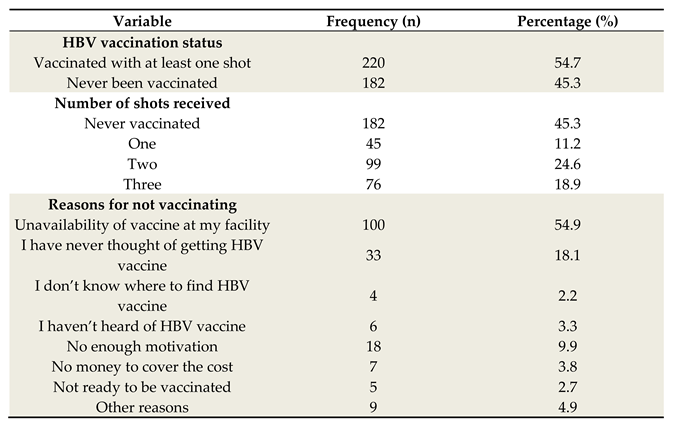

3.3. Uptake of Hepatitis B vaccine among HCWs

Among all interviewed HCWs only 18.9% (76 /402) were fully vaccinated. Most of those who had not received HBV vaccine (55% (100/182) claimed that availability of vaccine at their working facilities was the main hindrance.

Table 3 shows the vaccination status as well as the identified barriers.

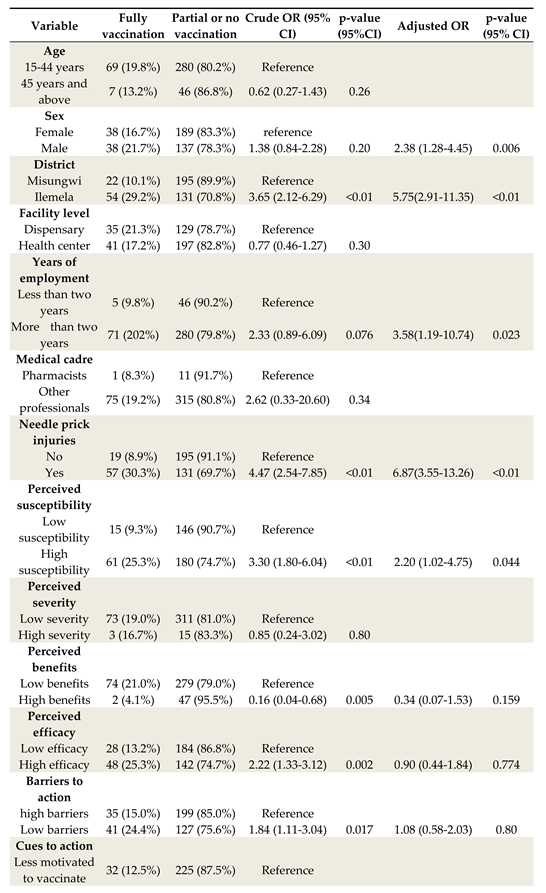

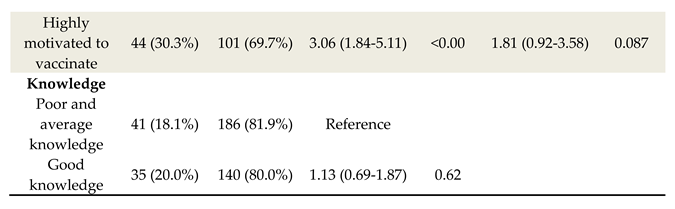

3.4.Comparison of vaccination status among HCWs in Ilemela and Misungwi districts

HCWs in Ilemela district were more likely to be fully vaccinated as compared to their counterparts in Misungwi (29.2% vs 10.1%; (aOR 5.75, 95% CI 2.91-11.35, p=0.01). Generally health care workers working in dispensaries showed higher hepatitis B vaccine completion compared to those working in health centers in both study areas, 21.35% versus 17.2% (aOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.46-1.27, (P>0.05.

Table 4 and figure 2 show the details of the above description. above

3.5.Factors associated with HBV vaccine uptake among HCWs

During multivariate logistic regression a number of the factors showed significant association with fully vaccination including sex of participants, district, duration of work, history of needle prick injury and high perceived susceptibility to HBV infection. Male participants had 2.38 higher odds of being vaccinated (aOR=2.38, 95% CI 1.28-.45, p=0.006) compared to females, Ilemela district HCWs were five times likely to be vaccinated (aOR=5.75, 95% CI 2.91-11.35, p<0.01) compared to HCWs in Misungwi and HCWs who had worked for more than two years had 3.58higher odds of being vaccinated (aOR-3.58 95% CI 1.19-10.74, p=0.023) compared to those who had worked for less than two years. On top of that participants who had high perception of susceptibility to HBV infection had 2.20 higher odds of being vaccinated (aOR=2.20, 95% CI1.02-4.75, p=0.044) compared to those who had low perception. In addition HCWs with history of needle prick injuries were six times likely to be vaccinated (aOR=6.87, 95%CI 3.55-13.26, p<0.01) compared to those who never encountered accidental needle stick injuries. Details of the above description are tabulated below (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Hospital acquired infections contribute to a significant Loss of human resource for health and affect quality of services. HBV infection is prominent among healthcare workers across the globe despite being a vaccine preventable disease. In Tanzania, studies of the uptake of HBV vaccine focused on healthcare workers in tertiary hospitals and little was known among those working in primary facilities. The aim of this study was therefore to determining the extent to which HCWs in primary health facilities are vaccinated against HBV and the associated factors.

This study revealed that less than 20% of HCW received full vaccination leaving others with no or partially vaccinated. The findings are different from studies at tertiary hospitals in Tanzania where completion rate was higher ranging from 33 to 70% [

8,

15,

16]. The difference in uptake could be attributed to vaccine availability, as in high level facilities HBV vaccine is usually available and sometimes free of charge [

16]. On the other hand HBV vaccine is not readily available at most primary health facilities in Tanzania as evidenced by this study. Therefore, it is important that the ministry of health consider HBV vaccine supply throughout lower and higher levels of facilities in order to increase uptake in these disadvantaged facilities. However, the findings are quite similar to the study conducted in Somalia where only 56% of HCWs had received HBV vaccine with very low completion rate of 16.6% [

17]. This shows that HCWs need to be sensitized more on vaccine completion because most of them showed higher non –completion status.

In this study only 43.5% of HCWs had good knowledge HBV infection. It is therefore important that HCWs get educated about occupational diseases, HBV of note in order to increase hepatitis B vaccine uptake among them as studies have shown significance association between good knowledge and HBV vaccine uptake [

16,

18].

Occupational risk of acquiring HBV infection was also explored in this study and it was found that splashes of body fluids from patients were the commonest occupational accidents, 83.1% followed by needle stick injuries 46.8%. The incidences of body fluid splashes is higher than that found in a study in Cameroon where only 56% of the participants reported similar accidents [

19]. This shows that HCWs are at risk of acquiring infections given their risk of needle stick injuries and body fluid splashes which might possibly be infected.

The factors that were found to be significantly associated with HBV vaccine uptake include sex of the participant, area of residence, duration of employment, history of needle prick injury and high perception of susceptibility to HBV infection.

Residents of Ilemela district showed higher rates of vaccine completion compared to Misungwi HCWs who represent the rural setting of the study. The findings exemplify studies in other regions of Africa where urban residents showed higher HBV vaccine uptake compared to rural residents [

20,

21]. This is because there is limited research as well as supplies in rural settings compared to urban settings, which could be a cause of this compromise. Therefore a focus should also be centered in rural health facilities in order to protect this vulnerable group.

Another factor that showed significant association with vaccination was history of needle stick injuries. Needle stick injuries are very common among HCWs, most studies report prevalence range between 40-65% [

6,

7,

22]. This predisposes them to the risk of acquiring HBV infection and therefore the need of vaccination to prevent infection acquisition. Therefore, this finding emphasizes on the need of sensitization campaigns among HCWs on infection prevention control strategies in order to reduce the risk of acquiring HBV along with other blood born infections. This will help increase vaccination rates among them and reduce the risk of acquiring HBV infection through occupational accidents.

Male respondents were more likely to uptake full vaccination than female participants in this study. This finding is incongruent from other studies conducted elsewhere in Africa where most of the studies reported higher vaccination coverage among female participants [

23,

24,

25]. This was related to the fact that females are usually couscous when it comes to disease prevention and control [

23]. The implication of this finding in our study is that men have now become more responsive to their health and are willing to take part in the whole process of diseases prevention.

Duration of employment was significantly associated with fully vaccination status among participants. Participants who had worked for more than two years were more likely to have complete vaccination compared to those who had less than two years of employment in this study. The findings are in line with the findings in Muhimbili national hospital where employees who had long duration of employment were likely to have vaccinated fully [

8]. Also studies conducted in Ghana and Uganda among medical students showed vaccination to be associated with advanced years of study among participants [

25,

26]. The cause of this may be increased understanding on HBV disease with years of work and study that drive HCWs and students to receive vaccines.

Moreover HCWs who perceived higher susceptibility to HBV infection showed a significant HBV vaccination rate. This is probably a good sign as this shows that with higher perception to infection, the prevention strategies are taken into account as evidenced by the study participants, however the vaccination rate is not satisfactory yet. The findings are in line with a study conducted among HCWs in Ethiopia who showed significant vaccination with perception of higher susceptibility to HBV infection [

7,

23]. However the finding is different from most other studies that showed that participants, perceived higher HBV infection susceptibility with still low vaccination rate [

6,

7,

22,

23]. Therefore national programs should emphasize vaccination as it is possible to vaccinate with higher perception of infection acquisition.

Most of studies focus on only knowing disease status and screening but no linkage to HBV vaccination centers, this study being an example. Therefore it is important to have more studies that screen, provide free vaccines and link the diseased HCWs to treatment clinics for follow up. The studies and campaigns should be done at least twice in a year in order to capture HCWs who are newly employed, as this study showed that those who had worked for less than two years were unlikely to have received HBV vaccine. This will help to increase coverage of HBV vaccination and hence reduce HCW-patient transmission of HBV. Moreover it is important to have HBV vaccination as a compulsory requirement before employment in order to increase vaccine uptake among newly employed HCWs.

5. Conclusion

This study showed low coverage of hepatitis B vaccine among health care workers despite the existence of risky of exposures. Therefore advocacy campaigns and HBV vaccines mobilization in primary health facilities are pivotal in order to save this important population group. Also there is a need for continuous medical training on infection prevention and control. HBV vaccine should be put as one of the pre-requisites for employment among HCWs so as to protect them from the risk of acquiring HBV infection during their practices. Further studies on sero prevalence are recommended among HCWs in primary levels of facilities in order to have reliable data on prevalence of HBV infection among HCWs in these facilities as well as HBV vaccine uptake.

Authors′ Contribution

BN, FM and AK designed the study and conception. BN and DW conducted and supervised data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the findings. BN and DW wrote the first draft of manuscript. SK, FM, MM and AK reviewed the manuscript critically and approved its submission. All authors approved submission the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and tools used and analyzed during the current study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement:

The assistance offered by the local authorities in Misungwi and Ilemela districts, health care workers, and all study participants is highly appreciated. We are thankful to Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS) – Bugando joint ethics and review committee for allowing this study to be conducted.

Competing interest

The authors affirm that they have no completing interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any grants from funding agencies in public, commercial or not-for profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Joint Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences Research and Ethics Committee-Bugando (CREC/573/2022). The approval was also granted by the district Medical officers of Ilemela and Misungwi districts and medical officers in charge of the health facilities where the study was conducted. Participants were recruited after getting an informed consent and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study process.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in the study granted their informed consent.

References

- Liu, T.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Siyin, S.T.; Zhang, Q.; Song, M. Associations between hepatitis B virus infection and risk of colorectal Cancer : a population-based prospective study. BMC Cancer 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.G.; Ge, Z.; Zhu, J.; Dai, J.; Du, L.; Yu, C.; Guo, Y. Associations Between Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Risk of All Cancer Types. 2019, 2, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.L.-H.; Wong, V.W.-S. Eliminating hepatitis B virus as a global health threat Building the evidence base to eliminate hepatitis B and C as. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1313–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global hepatitis report, 2017. In Proceedings of the Global hepatitis report, 2017; 2017.

- MoHCDGEC National Strategic Plan For The Control Of Viral Hepatitis; 2022.

- Nabil Al-Abhar, Ghuzlan Saeed Moghram, Eshrak Abdulmalek Al-Gunaid. 4 Occupational Exposure to Needle Stick Injuries and Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage Among Clinical Laboratory Staff in Sana’a, Yemen: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke E N, Ladep N G, Agaba E I. Hepatitis B Vaccination Status and Needle stick Injuries among Medical Students in a Nigerian University. Niger. J. Med. 2008, 17, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron, D.; Nagu, T.J.; Rwegasha, J.; Komba, E. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers at national hospital in Tanzania : how much, who and why ? BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Stoetter, L.; Kalluvya, S.; Stich, A.; Majinge, C.; Weissbrich, B.; Kasang, C. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, E.R.; Mboya, I.B.; Gunda, D.W.; Ruhangisa, F.G.; Temu, E.M.; Nkwama, M.L.; Pyuza, J.J.; Kilonzo, K.G.; Lyamuya, F.S.; Maro, V.P. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among healthcare workers in northern Tanzania. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Hepatitis B in the WHO European Region KEY FACTS.

- Adam, A.M. Sample Size Determination in Survey Research. J. Sci. Res. Reports 2020, 26, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, A.O.; Agunbiade, A.B.; Badmos, K.B.; Lesi, A.O. Prevalence of HBsAg, knowledge, and vaccination practice against viral hepatitis B infection among doctors and nurses in a secondary health care facility in Lagos state, South-western Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 23, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. HHS publlic access 2016, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzo, S.B.; Gunda, D.W.; Mpondo, B.C.T.; Bakshi, F.A.; Jaka, H. Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Tanzania: Current Status and Challenges. J. Trop. Med. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elichilia, R. Shao, Mboya, I.B.; Lyamuya, F.; Christian, K.; Centre, M.; Kilonzo, S.B.; Sciences, A.; Gunda, D.W.; Sciences, A. Uptake of Cost-free Hepatitis B vaccine among Health care workers in Northern Tanzania. Tanzania Med. J. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.A.; Ismail, A.M.; Jama, S.S. Assessment of Hepatitis B Vaccination Status and Associated Factors among Healthcare Workers in Bosaso, Puntland, Somalia 2020. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alege, J.B.; Gulom, G.; Ochom, A.; Kaku, V.E. Assessing Level of Knowledge and Uptake of Hepatitis B Vaccination among Health Care Workers at Juba Teaching Hospital, Juba City, South Sudan. Adv. Prev. Med. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noubiap, J.J.N.; Nansseu, J.R.N.; Kengne, K.K.; Ndoula, S.T.; Agyingi, L.A. Occupational exposure to blood, hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and uptake among medical students in Cameroon. bmc Med. Educ. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangura, M.; Frühauf, A.; Mhango, M.; Lavallie, D.; Reed, V.; Rodriguez, M.P.; Smith, S.J.; Lakoh, S.; Ibrahim-sayo, E.; Conteh, S.; et al. Screening, Vaccination Uptake and Linkage to Care for Hepatitis B Virus among Health Care Workers in Rural Sierra Leone. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Id, K.H.; Id, A.T.; Mose, A.; Id, Z.M. Hepatitis B vaccination status and associated factors among students of medicine and health sciences in Wolkite University, Southwest Ethiopia : A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, O.; Nc, A. hepatitis b vaccination status and needle stick injury exposure among operating room staff in lagos, nigeria l ’ État de vaccination contre l ’ hÉpatite b et la piqure d ’ aiguille de seringue. l ’ exposition parmi les personnel de la salle d ’ opÉratio. J. west African Coll. Surg. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Abeje, G.; Azage, M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia : a cross sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Id, A.A.; Id, A.F. Knowledge, risk of infection, and vaccination status of hepatitis B virus among rural high school students in Nanumba North and South Districts of Ghana. PLOSONE 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniaku, J.K.; Amedonu, E.K.; Fusheini, A. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Vaccination Status of Hepatitis B among Nursing Training Students in Ho, Ghana. Annu. Glob. Heal. 2019, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Id, Y.W.; Banura, C.; Kalyango, J.; Karamagi, C.; Kityamuwesi, A.; Amia, W.C.; Ocama, P. Hepatitis B vaccination status and associated factors among undergraduate students of Makerere University College of Health Sciences. 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).