1. Introduction

Member states of the United Nations (UN), including Ethiopia, adopted the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by general assembly resolution A/RES/70/1 on 25 September 2015[

1]. The resolution set 17 interlinked goals to be achieved by 2030. The first and second goals of the SDGs were described as 'No Poverty' and 'No Hunger' for short. The former aims at the alleviation of poverty in all its forms everywhere, and the latter intends to end hunger, achieve food security, and improve nutrition through sustainable agriculture. Although all the SDGs are very important across the globe, these two goals are even of particular importance in the context of Ethiopia, where tens of millions of the population is food insecure and a significant percentage of its citizens live below the national poverty line (Reliefweb 2022; UNDP 2018a).

Ethiopia has around 74.3 million hectares of arable land, spreading well over 18 agroecological zones, making the country suitable for growing over 100 types of crops(ATA 2021). The country is also blessed with 12 river basins with an annual runoff volume of 122 billion m3 of water(Awulachew et al. 2007). Despite all this and being an agricultural-based economy, the country has faced significant challenges in achieving food security and reducing poverty levels.

Several studies have agreed that practicing sustainable irrigated farming is a crucial tool in improving the incomes of farm households(Asrat et al. 2022), ensuring food security (Tesfaye et al. 2008), and alleviating poverty in general (Bacha et al. 2011; Gebregziabher et al. 2009). Irrigation does this by increasing agricultural productivity, reducing dependency on rainfall and protecting crops from drought(Chai et al. 2016; Mashnik et al. 2017; Sithole et al. 2014). This, in turn, can lead to higher incomes for farmers and improved food security for communities. Irrigation also greatly contributes indirectly to improving human health as it promotes a balanced diet and access to medication (Ahmed 2019). Additionally, irrigation can also provide employment opportunities, stimulate economic growth, and increase access to markets (Van Den Berg and Ruben 2006).

Taking note of this the Ethiopian government have been working intensively since recently to revolutionize the irrigation sector. Irrigation in Ethiopia faces various challenges such as an insufficient infrastructure, poor mechanization and lack of technical expertise. To overcome these challenges, the Ethiopian government and development partners have been working to develop and improve the country's irrigation systems. Some of these efforts include the construction of dams, canals, and other water infrastructure, as well as the training of farmers in efficient irrigation techniques. The impact of these efforts can be seen in the significant growth of the country's agricultural sector and the improvement of food security for communities. In addition, the expansion of irrigation has also helped increase income levels, particularly for small-scale farmers who make up a significant portion of the country's population.

With this view, this paper aims at shading a light on the major pathways through which irrigation contributes to food security and economic improvement both at household and national level in Ethiopia. Because understanding this helps to manipulate the pathway in away the sector becomes of an even better contributor to the country’s fight to feed and prosper its population, thereby realizing the SDGs.

2. Irrigation Potential of Ethiopia

Irrigation potential is the total land area that is technically feasible, economically profitable, socially viable, and environmentally acceptable that is irrigated or capable of being irrigated based on water and land availability(LI 2022). The estimation of the irrigation potential of a region may vary a lot from study to study or from time to time. Country or regional studies estimate irrigation potential based on a variety of criteria. For instance, some take into account land resources only, others consider water availability, and the rest may take into consideration the environmental and economic conditions of the country, etc (Knaome 2019). You et al. (2011) considered factors like production geography, the potential performance of irrigated agriculture, potential runoff, irrigable area, associated water delivery costs, etc., in the assessment of the potential for irrigation investment. Recently, models, remote sensing, and GIS technologies are becoming researchers’ favorites in determining the irrigation potential of a region. Yimere and Assefa (2021) used the ‘mike hydro model’ to assess and map irrigation potential in the Abbay river basin of Ethiopia. Remote sensing and GIS have been used to assess the irrigation potential of a canal system in India (Reddy et al. 2017). Such deviations in assessment and estimation strategies lead to ambiguous and inconsistent reports on the irrigation potential of countries, the same is true for Ethiopia.

Most of the classic irrigation-related survey studies in Ethiopia came from the work of the iconic Engineer Seleshi B. Awulachew and his colleagues at IWMI (Awulachew et al. 2010; Awulachew and Ayana 2011; Awulachew et al. 2005; Awulachew et al. 2007). Engr. Awuachew is well known for his role as the chief negotiator in the trilateral negotiations, between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt, in regard to the grand Ethiopian renaissance dam. According to Awulachew et al. (2010), about 5,300,000 hectares of land in Ethiopia can be potentially irrigated. This has shown an advance of about 28.3% over the estimation by Awulachew et al. (2007), which estimated the country’s irrigable land to be 3,798,782 ha. The variation arises from the fact that Awulachew et al. (2010) included harvested rainwater and groundwater, which has the potential of irrigating an additional 1,600,000 ha of land. Furthermore, Nakawuka et al. (2018) put Ethiopia’s irrigation potential to be 2,700,000 ha. Similarly, in 2016, the food and agricultural organization (FAO) estimated the irrigation potential of Ethiopia at about 2.7 million ha, based on the availability of water and land resources, technology, and finance(FAO 2016) . FAO even outlined the hectarage and percentage contribution of each drainage and river basin in the same report. This is a typical manifestation of variation in the estimation of a country’s irrigation potential, even by a similar author, based on things taken into consideration during the study/ survey.

Currently, the total groundwater resource of Ethiopia is estimated to be 27.27 billion m3 (ATA 2021), which has a 76.2% increase compared to the highest estimation, 6.5 billion m3 (Awulachew et al. 2007). This variation in the estimation of groundwater resources makes sense as the total groundwater resources mapping area has increased from time to time and currently sits at 234,772 km2 (ATA 2021). The Ethiopian agricultural transformation agency (ATA), in its latest (2020/21) annual report, stated that the country has an irrigation potential of 3,088,395 ha which can support 6,176,898 farm households. However, one can realize that the irrigation potential of Ethiopia estimated by Awulachew et al. (2007) and Awulachew et al. (2010) a decade or more ago are superior by 23% and 71.6% respectively, to the current estimation by ATA (2021).This gets difficult to accept, especially when realizing the currently estimated groundwater resource of the country has increased dramatically (quadrupled) compared to the estimation in earlier times, 2.6–6.5 billion m3, (Awulachew et al. 2007). Well, again, this discrepancy is maybe related to the differences in the assessment strategies and criteria considered in the studies. With all this in mind, for the sake of this paper, we will make our arguments and discussion based on the latest report on the country’s irrigation potential by ATA (2021).

3. Total Irrigated Land in Ethiopia

Although Ethiopia has the largest irrigation potential in East Africa, followed by Tanzania and Kenya, it uses only a small portion of it (Nakawuka et al. 2018). In its latest annual report, ESS estimated the total irrigated land for 2020/21 by private peasants to be only 181,395 ha, practiced by around 1.4 million households (ESS 2021). Sadly, this is only 5.9% and 22.7% of the total land area and the number of farmers respectively, the country’s irrigation potential could support (ATA 2021).

However, most authors report the percentage of irrigated land to irrigation potential of the country based only on land area irrigated by private peasant holdings, ignoring those by commercial farms and sugar estates (Ahmed 2019). This is because though the ESS releases survey reports on different aspects of the private commercial farms, it does not include the areas irrigated by those farms. Hence, it is difficult to obtain data on trends in irrigated land areas by commercial farms. However, by considering at least the recent report on the area irrigated by the sugar estates of the country, we might get some more insights into the percentage of the irrigation potential used. According to the Ethiopian sugar corporation (ESC), currently, there are eight sugar estates involved in irrigated sugarcane production on an area of 145,030 ha (ESC 2019b). So, if we sum up the total irrigated land by private peasant holdings and the sugar estates, the total estimated irrigated land area would be 306,425 ha, and this again makes up only 10% of the country’s irrigation potential. His excellency, Dr. Abiy Ahmed, prime minister of Ethiopia, in his welcoming speech at the opening of the 35th ordinary session of the African Union (AU) on the 5th February 2022, said:

“… Nationally, we have attained production of 20 million quintals of irrigated wheat farmed over 500,000 hectares. This has generated nearly 60 billion birrs in income to our farmers”.

One of the main points to take hold of this speech is the claim by the prime minister that nationally a total of 500,000 ha of land is under irrigated wheat production. The claim seems strange as ESS (2021) estimated only 181,395 hectares of irrigated crops in the 2020/21 cropping season. Thus, the Prime Minister's claim may be based on the work done during the ' Meher' season of 2022, which in any case requires confirmation when the ESS 2022 report is issued. Regardless, even if the estimate by the ESS on irrigated land by private peasants, the report on the area irrigated by sugar estates from ESC, and the claim by the prime minister are considered as the total area currently under irrigation (806,425 ha), would still be only 26.1% of the irrigation potential of the country. This is a clear indicator of how long the country has left to go in improving the irrigation sector. This is very important, especially when realizing that estimated 5.7 million people live in the misery of hunger (WFP 2022) and around 22 million people live below the national poverty line (UNDP 2018b).

4. Importance of Irrigation to Food Security in Ethiopia

The 1996 world food summit defined food security as “a state in which all people, at all times, have physical, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. This definition lays down four preconditions to be fulfilled for a country or a household to be considered food secure viz., food availability, access to food, food utilization, and stable supply of food (Gross et al. 2000). The fulfillment of these four dimensions is mostly related to the agricultural production status and the economic capabilities of households or countries to produce, and acquire/import foods (Leroy et al. 2015; Pawlak and Kołodziejczak 2020; Simon 2012).

Ethiopia has experienced a significant increase in food insecurity in recent years due to droughts, floods, and other natural and man-made disasters, (Ayinu et al. 2022; Lewis 2017; Mohamed 2017). This has put immense pressure on the government and local communities to find solutions to the challenges posed by these changing environmental conditions. Currently there are a huge number of people, as high as 15 million, who are food insecure and in need of immediate humanitarian food assistance(Fews-net 2022). According to the 2022 Global Hunger Index (GHI), Ethiopia has GHI score of 27.6, which puts the country 104th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate GHI scores (GHI 2022). This is very concerning as a significant percentage (nearly 15%) of the population is facing hunger and the country has a very poor GHI score which indicate a very serious hunger level.

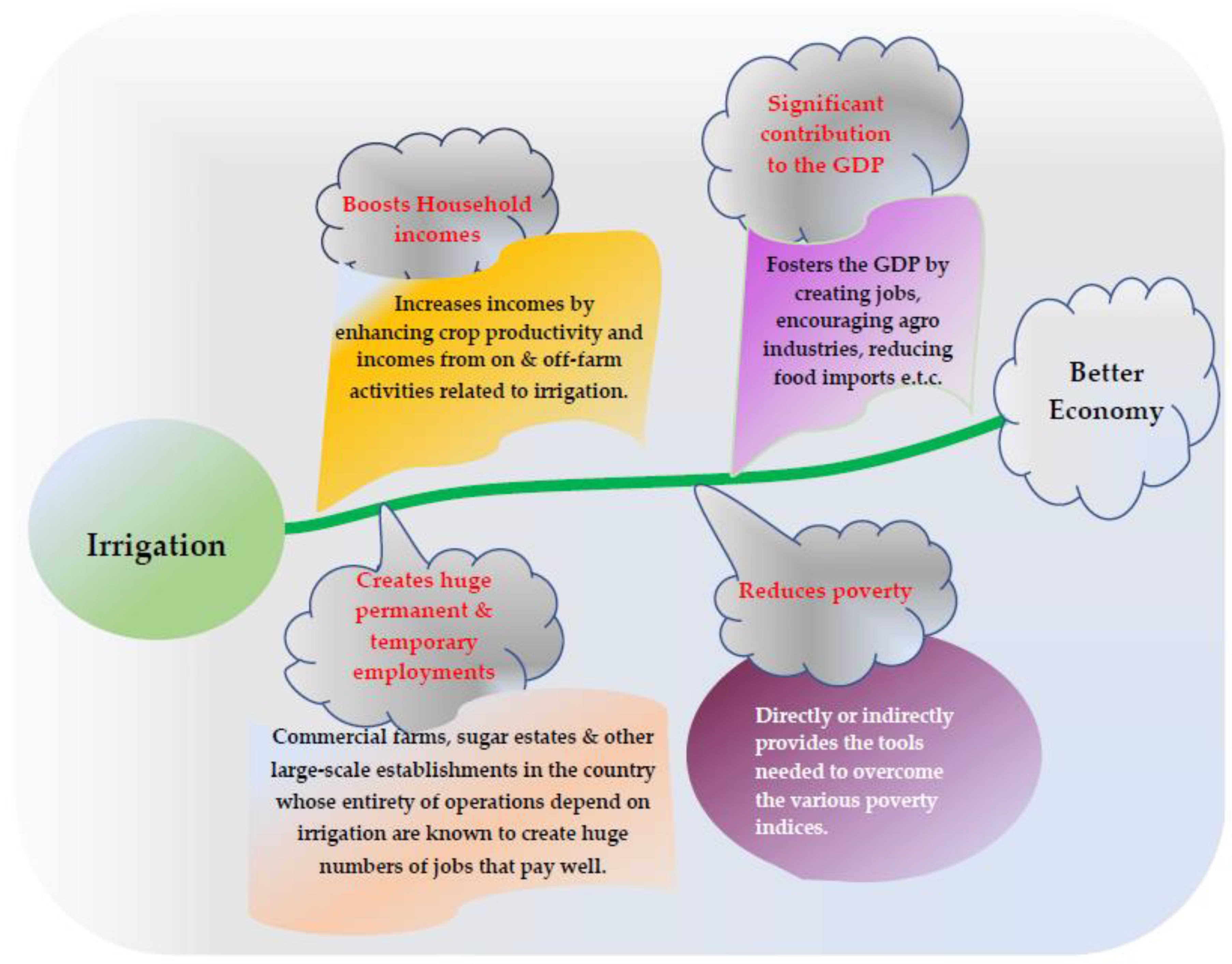

Irrigation has been identified as one of the most effective ways of addressing these challenges and ensuring food security in Ethiopia. Irrigation systems allow for the controlled and efficient use of water for agriculture, which leads to increment of crop yields and improvement of food production. Irrigation is also witnessed to contribute to food security in the country by reducing the risk of crop failure, and generating higher and year-round farm and nonfarm incomes (Hussain and Hanjra 2004). This, in turn, leads to more stable food supplies and improved food security for the population. Generally speaking, Irrigation has been shown to contribute to all the dimensions of food security through various direct and indirect pathways (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Contribution of irrigation to the different dimensions of food security in Ethiopia.

Figure 1.

Contribution of irrigation to the different dimensions of food security in Ethiopia.

4.1. The Contribution of Irrigation to Food Availability

The food availability dimension of food security is mostly related to the general food supply status of an area which is dependent on the totality of domestically produced and imported food products (Gross et al. 2000). Irrigation is reported to increase crop productivity (Ogunniyi et al. 2018; Tilahun et al. 2011) and ensuring year-round crop production (Kim et al. 2020; Sekyi-Annan et al. 2018), which are the two major determinants of food availability to a community. keeping other factors controlled, higher crop productivity and multiple production per year ensures sufficient supply of food in the market.

The major way through which irrigation promotes food availability is by boosting crop productivity through yield increment (Adu et al. 2018; Sarwar et al. 2010). A higher onion yield (46.7t/ha) was obtained when the crop was fully irrigated throughout its different growth phases compared to when it faced water shortage at some point of its growth (Temesgen et al. 2018). supplementary irrigation was shown to significantly improve grain yield and other yield related parameters of sorghum in North Eastern, Amhara of Ethiopia (Wale et al. 2019). Irrigation, was shown to increase the yield teff (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter) by 16% -168% under different soil fertility regimes and sowing periods in Tigray region (Tsegay et al. 2015). Overall, such increased crop yields are one of the drivers of food availability in area, as the basics of economics tells us higher production means higher supply. Not only that but an increased production in one country leads to a surplus which eventually is exported to other countries with lesser food, hence increasing food availability in the importing country.

The other important way through which irrigation promotes food availability is by encouraging multiple production per year. A significant proportion of irrigation users, as high as 32.1%, in northern Wollo were reported that their crop production frequency increased due to irrigation (Mengistie and Kidane 2016).Farmers in Haramaya district of eastern Ethiopia were reported to produce more than two times a year using irrigation, which has led to them to be food self-sufficient (Dawit et al. 2020).

Irrigation doesn’t promote food security only through the increment of crop productivity or production frequency. Irrigation may also directly or indirectly contribute through exposing the farmers to other sources of food. For instance, irrigation users in Arsi zone of Ethiopia were in better position when it comes livestock possession (7.58 to 4.38 TLU) and oxen ownership (1.78 to 1.12 TLU) compared to rainfall dependent farmers (Eshetu and Young-Bohk 2017). Livestock and poultry possession make other types of foods such as, dairy products, meat products and eggs available to the households. Furthermore, irrigation is also an important factor in preventing potential future food shortage. This was noticed where supplemental irrigation was modeled to improve food security in the rift valley drylands of Ethiopia by increasing the yield of maize under different climate change scenarios (Muluneh et al. 2017). Therefore, attention must be given to enhancing food productivity and intensifying crop production through irrigation in order to avoid food availability issues at the present time and any potential future food shortage in the country.

4.2. The Role of Irrigation in Promoting Access to Food

Food availability in the market/area by itself doesn’t necessarily ensure food security. Because at the end of the day the community have to be able to buy or acquire the available food through different means. This tendency to acquire the available food, is mainly dependent on the importing power of the country from the global market or purchasing power of the households from the local market. This is what is called the ‘access’ dimension of food security. Therefore, irrigation improves access to food by boosting the crop productivity at the farm which then the farmer could consume right away or sell it to generate income to acquire other food items (Li et al. 2020; Ogunniyi et al. 2018)..

Irrigation has been reported to improve household food consumption and expenditure of its users in different parts of the country. Food consumption expenditure is an important aspects of household socioeconomic conditions which reflects food acquisition and consumption or purchasing power. The household food consumption expenditure of irrigation users in western Oromia was ETB 1631(USD 71), higher than those households not practicing irrigated crop production (Abdissa et al. 2017). The mean annual consumption expenditure for irrigation users in northern Ethiopia was 114%, higher than that of the irrigation non-users (Nugusse 2012). Similarly, households in eastern Ethiopia were reported to enjoy 16% higher per capita consumption expenditure compared to their counterfactual group (Asrat et al. 2022) .

The other major way irrigation creates better economic condition to access food is by improving the likelihood to get loans. Irrigation users in Ethiopia are 23% - 52% more likely to getting a credit compared to those not practicing it (Tefera and Cho 2017). Households, who had access to credits, in Afar region, were shown to be more food secure (by a factor of 6.52) over those household who didn’t get access to credits (Getaneh et al. 2022). The rationale behind this is that credits create a purchasing power to households, which enables them to get access to high value diversified nutritious food in the case of short market supply.

Access to the available food may also depend on the overall political and civil stability of the region or the country. A typical example of people not getting access to food regardless of its availability in Ethiopia is the recent cruel war in northern part of the country. Numerous international aid organization, reported they were unable to provide food to the war affected community despite having food stocks in their depots (Jerving 2022; Reuters 2020). This was mainly due to the extreme risk to their aid workers (Aljazeera 2020) and the permit restriction by the government that accused the aid organization of intervening in its internal affairs (AP-news 2021).

The problem with food access in Ethiopia can be addressed in three possible ways(Jayne and Molla 1995);

- (i)

With direct food aid (food transfers) to affected households

- (ii)

By incapacitating poor households economically

- (iii)

By reducing food prices in the market by boosting productivity across the food system.

However, the first route (food aid) is dubbed outdated or inefficient, unless in case of emergency food access issues, as it creates a sense of dependency and reluctance to work towards food self-sufficiency(Barrett and Lentz 2010; Paynter et al. 2011). Therefore, the focus always should be on putting a leash on the food market and increasing household incomes. Irrigation plays a huge role in both respects as it improves household incomes and stabilizes the food market with increased production outputs, hence promoting access to food.

4.3. Irrigation and Food Utilization in Ethiopia

The ‘utilization’ dimension of food security is often related to the likelihood of individuals/households to consume all the nutritious and diversified food groups that will result in a healthy life style. This may encompass sufficient energy and nutrient intake by individuals as a result of availability of food and having access to it.

Irrigation was shown to increase the daily per capita intake of households in different parts of Ethiopia. According to a study in Oromia region, farmers participating in small-scale irrigation tend to intake 643.76 Kcal more daily calories compared to farmers dependent only on rainfed agriculture (Jambo et al. 2021). In Arsi zone, only 26.25% of the irrigation users intake a daily calorie of less than 1500 Kcal while on the other hand, the percentage was almost double, 49.2%, for non-irrigation users (Tefera and Cho 2017). Similarly, access to irrigation was reported to have increased food intake of food insecure households’ in western Ethiopia, by a colossal amount of around of 7098%(Sani and Kemaw 2019).

Irrigation provides better household dietary diversity. Irrigating households in Ethiopia were reported to have higher production and dietary diversity as a result of their tendency to produce more vegetables, fruits, and cash crops, compared to non-irrigating households (Passarelli et al. 2018). Jebessa et al. (2019) found that access to irrigation was among the most important determinants of household dietary diversity. This was supported by their finding in which dietary diversity of households with access to irrigation was higher by a factor of 5.824 than those households with no access to irrigation. The mean household dietary diversity score for the seven food groups consumed in kobo town was found to be 3.84 and 3.21 respectively for those who participate in irrigation and those who don't (Mengesha 2017). The calculated food consumption value for irrigation users and non-users of the same town was 44.89 and 41.64 respectively.

Irrigation also improves maternal dietary and nutritional status of children. Women from households that practiced irrigation in Robit and Dangila districts of the Amhara region had a higher dietary diversity coupled with higher vitamin C and calcium intakes compared to women from non-irrigating households (Baye et al. 2021). Irrigation also improved dietary diversity of women from households that allegedly encountered drought by around 9% in Ethiopia (Mekonnen et al. 2022). The same study also revealed that irrigation improved the nutritional status of Ethiopian children under the age of five manifested by the improvement of weight-for-height z-scores of the children by 0.87 SDs. This phenomenon is very important in the realization of the SDG as it provides women and children with nutritious food, keeping mothers and their babies, well fed and healthy.

4.4. The Role of Irrigation in Creating Stabilized Food Security

The ‘stability’ dimension of food security refers to the consistent availability, accessibility and utilization of food by an individual, household or a society across time and space. This means that in order for a country to be considered to have a stable food security food must be available, accessible and utilized by its community at each level, at all places and at any time. Hence, stable food security is a factor of the prevalence of all the factors contributing to food availability, accessibility and utilization. In another term stable food security is the factor of, economic power, production capacity, peace and stability as well as individual or societal knowledge, culture and practice of food utilization.

Irrigation is shown to improve the overall food security status of households practicing it. About 70% of farmers deployed in small-scale irrigated crop production in the Ada-liben district tend to be food secure whereas the food security status of rainfed producers was only 20% (Tesfaye et al. 2008). A study in the Sibu-sire district found that food insecurity was 27% and 56% among small-scale irrigation users and non-users respectively, which means the respective food security status was 73% and 44% for the former and the latter (Kelilo et al. 2014). Households with larger irrigated crop production hectarage were also reported to be more food secure and as having better copping response to food insecurity factors (Getaneh et al. 2022).

Irrigation was found to be among the major determinants of food security in different parts of Ethiopia. Distance of households from irrigation water source in the central highlands of Ethiopia, were shown to affect the tendency of the households to use irrigation or not(Muleta et al. 2021) . This in turn has affected the likelihood of households to be food secure in the district; those closer to the irrigation water source being more likely to use irrigation, hence produce more and become more food secure. furthermore, it is argued that the future of agricultural development and food security in Ethiopia to a great extent is a factor of to what degree the country intensifies irrigated crop production (Adenew 2004). Hence, all these studies indicate the importance of irrigation to the attainment of stable food security, hence the realization of the SDGs in Ethiopia.

5. Importance of Irrigation in the Ethiopian Economy

Agriculture could simply be put as ‘the backbone of the Ethiopian economy’. This is because agriculture accounts for about 32.5% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and 85% of its employment (FAO 2022; USAID 2022). Since, agriculture holds such a place in the overall economy of the country and the livelihoods of Ethiopian households, its necessarily to take the subject of irrigation seriously. This is not just for Ethiopia but other developing countries whose economy is largely dependent on agriculture.

Rainfed agriculture draws relatively lesser income from the same plot of land compared to irrigated agriculture. The dependence of Ethiopian agriculture on rainfall, and its variability, hampers the crop production and productivity of millions of smallholder farmers. Rain-fed agriculture is less efficient both in terms of water use and profitability compared to irrigated agriculture (Tilahun et al. 2011). This is attributed to the decline in crop productivity resulting from the provision of inappropriate doses of water (water deficit and water-logging) from rainfall variability in rain-fed agriculture (Kyei-Mensah et al. 2019). Such decline in agricultural productivity leads to a drastic reduction on the income from the sale of agricultural products at household level and in foreign currency earnings from the exports at the national level.

Irrigation comes as a rescue to such challenges of rainfed agriculture. Irrigation contributes to the development of export-oriented crops, such as fruits and vegetables, which can generate foreign exchange earnings for the country. The economic impact of improved agricultural productivity due to irrigation is more pronounced in developing countries like Ethiopia that depend largely on agriculture for their livelihood, foreign earnings and GDP. There are so many direct and indirect pathways in which irrigation may contribute to the economy of Ethiopia (

Figure 2), some of which are discussed in the sections to follow.

5.1. The Role of Irrigation in Boosting Household Incomes

Irrigation has led to the diversification of crops grown in Ethiopia, leading to the introduction of high-value crops such as fruits, vegetables, and spices. The production of these crops opens up new markets for Ethiopian farmers, increasing their income and contributing to the country's economic growth.

A study found that the average income of farmers practicing rain-fed agriculture in Ethiopia, USD 147 ha-1, is much lower compared to the average income of approximately USD 323 ha-1 generated by farmers practicing irrigated farming (Hagos et al. 2009). This shows a 54.5% income difference between the farmers practicing rain-fed agriculture solely and the income of smallholder-managed irrigation systems. Participation in irrigated crop production in Tigray increased household income and asset accumulation by nearly 9% and 186% respectively, compared to non-participants(Gebrehiwot et al. 2017). Similarly, the mean annual income and asset accumulation for irrigation users in northern Ethiopia were respectively 97% and 103% higher than that of the non- irrigation users (Nugusse 2012). Similarly, households in eastern Ethiopia were reported to enjoy 35% higher per capita income compared to their counterfactual group (Asrat et al. 2022). Similarly, Households, in north-easter Ethiopia, with irrigation access had around ETB 7829/ USD 200 (8.5%) more income compared to their non irrigating counterparts (Assefa et al. 2022).

In some places irrigation contributes the largest annual income compared to any other income source of farm households. For instance, Irrigation contributed around 71.5%, 74.4% and 76 % of the total annual income of three consecutive years (2011-13) in Gum-salesa district of southeastern Tigray (Tedros 2014). Similarly, the contribution of irrigated crop production to the total annual income of households in Shilena district of the same part of the country was around 70.2% 74.73% and 78% as compared to other sources of income.

Research in the rift valley lake basin, a huge area covering 52,739 km

2 and possessing an irrigation potential of 45,700 ha, has also showed farmers deployed in irrigated crop production earn an annual mean income of ETB 10161.5 (USD 188.17) per household, which is 33.6% higher than that of farmers relying merely on rainfall (Eneyew et al. 2014). These figures would have made a visible impact on the national economy in aggregate, as currently 12 million smallholder farming households are involved in agriculture. They account for estimated 95% of agricultural production in the country (ESS 2021; FAO 2022). The following table (

Table 1) shows the income difference irrigation users and non-users observed across some time and space at different administrative levels in Ethiopia.

However, the degree of contribution of irrigated crop production as a tool to alleviate poverty and create equity depends on the type of irrigation technology used. A comprehensive study assessing the role of agricultural water management (AWM) technologies in poverty alleviation showed that the poverty incidence among nonusers was 15% higher than the technology users (Hagos et al. 2012). The same study revealed the poverty gap and severity were 0.28 and 0.17 respectively for nonusers, whereas it was only 0.19 and 0.11 respectively for users. The degree of poverty reduction also depends on the AWM technologies used, with 37, 26, and 11%, respectively for deep wells, river diversions, and micro dams (Hagos et al. 2012). Households possessing motorized water pumps in Tigray were reported to have higher agricultural productivity leading to significantly higher income compared to those not using mechanized irrigation (Gebrehiwot et al. 2015). This underscores the importance of adopting better irrigation management technologies for better and faster poverty reduction in the country.

5.2. The Role of Irrigation in Providing Employments

Irrigated crop production is witnessed to create numerous employment opportunities and a better pay rate than rain-dependent farming. This is because irrigated crop production is labor-intensive and requires more work force for its construction, maintenance and operation compared to rain-fed agriculture (Wana and Senapathy 2022). In addition, the increased agricultural production due to irrigation leads to the creation of jobs in processing, storage, transportation, and marketing of agricultural products. Therefore, irrigation creates temporary and permanent employment opportunities which generate good pay checks.

The hours spent and the pay rate for operation of irrigating farming is better than that of rainfed farming. Mean hours invested in the irrigated farm operation and the associated labor cost in Wolaita were significantly higher than the rain-fed farms for all activities including, plowing (71%), weeding (70.8%), harvesting (67.6%) and trashing (65.86%) (Zemarku et al. 2022). The labor cost per ha for irrigated farms of the same area was also relatively higher (535.94 ETB~10.72 USD) compared to the rain-fed (305.92~6.1), the former creating 42.9% more pay than the latter. Similarly, irrigation was shown to create a total of 30-210 days of employment and generated 2035–8635 total wages per laborer during irrigated crop production activities in four irrigation schemes in north Wollo of Ethiopia (Mengistie and Kidane 2016). This indicates the potential of irrigated crop production in generating more employment and a better pay rate per task compared to rain-fed farming. Hence, given agriculture provides a large chunk of the country’s employment, expanding irrigated farming would create sustainable jobs and better income for employees, thus aiding in the attainment of the SDG through poverty alleviation.

Another interesting area in which irrigation creates enormous number of jobs is via the large sugar estates and commercial farms whose existence and operation are entirely dependent on irrigation(Fantini et al. 2018). Currently, there are around 9 sugar states and several other large scale commercial farms which have created tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of temporary and permanent job opportunities (

Table 2).

5.3. The Contribution of Irrigation to the National GDP

It’s always difficult to discuss irrigation by separating it from the general picture of agriculture. However, since production of high value crops and year-round productions are almost impossible without irrigation we will be pretty much talking about irrigation when we talk of the contribution of agriculture to the economy.

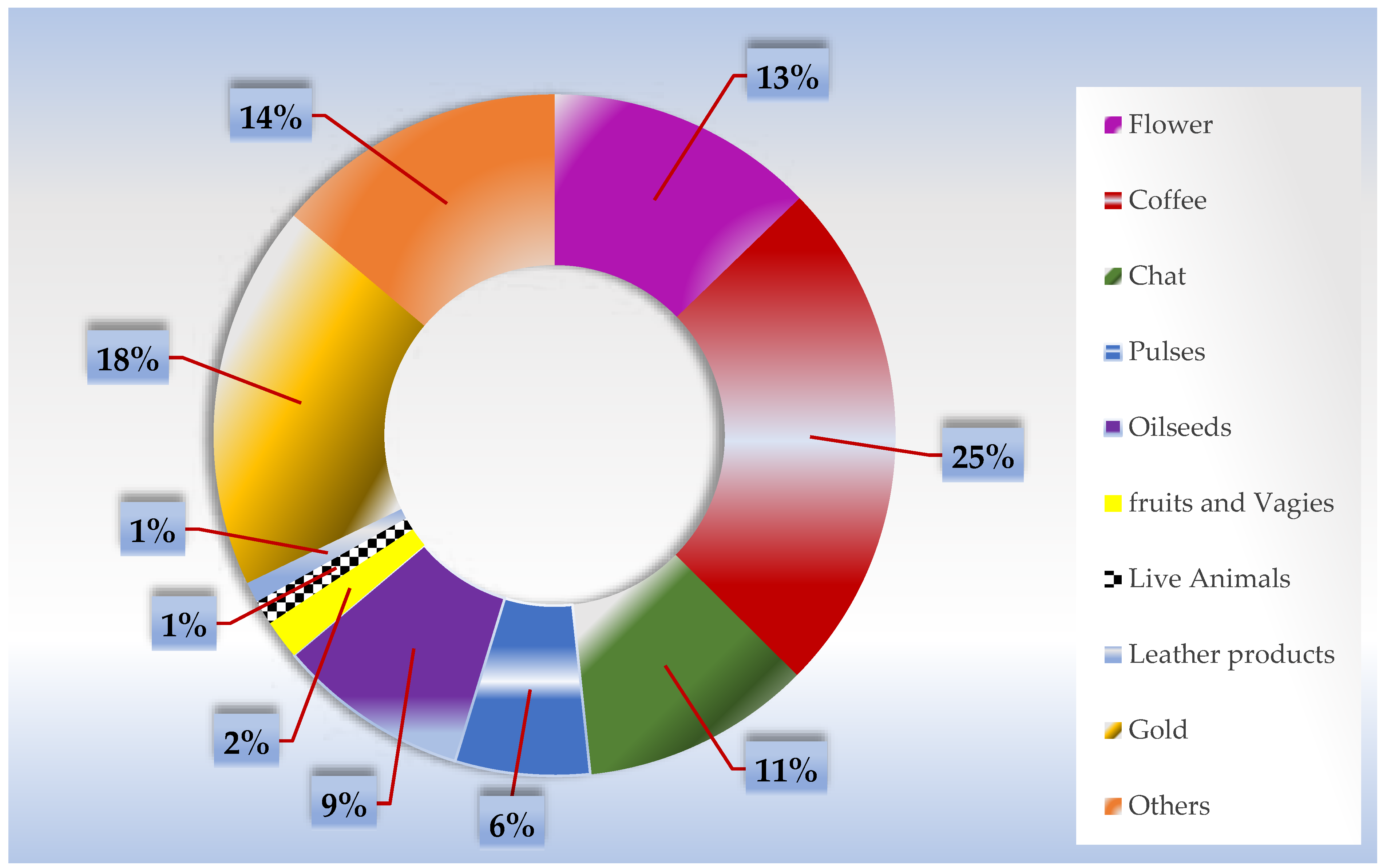

One of the major contributors to a country’s’ GDP is its export and the same is true for Ethiopia. As a country following an agriculture led industrialization economic development policy, agriculture accounts for the majority of Ethiopian export commodities and foreign currency earnings. To be precise of the total merchandise export, agricultural commodities take the lion share with 67% of it (

Figure 3). This also implies that agriculture brings 67% of the total foreign currency earnings.

Such high export and foreign currency earnings which greatly uplifts the country’s GDP, doesn’t just come from rainfed agriculture. Instead, most of the high value crops bringing in the huge foreign currencies and accounting for the largest export shares are produced using irrigation. For instance, flowers make up 13% of the total annual export merchandize of the country and obviously the entirety of water required for flower production comes from irrigation. The same goes for other crops such as pulses and oilseeds, as its difficult to generate the desired export earnings with just once a year rainfed farming but with a year-round production using irrigation.

To the best of our knowledge, the only study linking the contribution of irrigated agriculture to the GDP of Ethiopia came from Hagos et al. (2009). The authors estimated the contribution of irrigated crop production to be approximately 5.8 and 2.5%, respectively to the agricultural GDP and the overall national GDP during the 2005/2006 cropping season (

Table 3).

The same authors also predicted the contribution of irrigation to the agricultural [8.8%] and overall GDP (3.7%) during the 2009/10 cropping season. These improvements were about 36.6% and 28.6% respectively, compared to the previous estimation in the 2005/2006 cropping season (Hagos et al. 2009). However, it was difficult to confirm whether the prediction for the 2009/10 production season was held or not.

Moreover, it hard to find recent studies of such type linking the contribution of the irrigation sector to both the agricultural and the overall GDP. Therefore, its necessary to develop research designs which help to determine or quantify the contribution of irrigated crops to foreign earnings and the GDP at least at annual basis. This would help to get an up-to-date insight into the performance of the irrigation sector, which can be used to improve and sustain the sector.

6. Opportunities to Improve Irrigation Development in Ethiopia

Having more than 3-million-ha irrigation potential which could support well above 6 million farmers, capable of pulling millions out of poverty and hunger is the principal opportunity. Furthermore, ATA is leading various projects with the aim of exploring and mapping the country’s groundwater resource to further expand the irrigation potential of the country. What’s needed is the mechanization of the irrigation system, expanding the irrigated area, and increasing the number of farmers involved in irrigated crop production.

Though gaps were observed in the implementation of drafted strategies, the governments of Ethiopia have always been very keen to expand the irrigation sector. This was true from the imperial regime to the Dergue government through to the Ethiopian people’s revolutionary democratic front (EPDRF) and the current ruling government ‘Prosperity’. The Ethiopian government has been working to use irrigation as a tool to achieve food self-sufficiency and economic improvement both at the household and national levels. One such work is the agriculture sector policy and investment framework (PIF) which approved a major irrigation development investment back in 2010 (MOA 2011). The PIF allocated about 38% of its 10-year (2010–2020) financial plan, USD 18 Billion, to irrigation development to achieve an 8% annual increase in arable irrigated land. On the other hand, the ministry of agriculture also launched a USD 47.97 billion worth, 15 years small-scale irrigation (SSI) capacity-building strategy which commenced in 2012 (MOA 2011).

Since taking office in 2019, prime minister Abiy Ahmed has been vocal about the need for the development of the irrigation sector on different stages from the African Union hall to his private social media accounts. At the inauguration of the Meki-Ziway irrigation project in May 2020, he said; “...The irrigation project is our top priority in the agriculture sector”. This indicates the commitment of the government to improve the productivity of smallholder farmers with an emphasis on the expansion of irrigated crop production. This is very important as the government is a key player in the development of the irrigation system in particular or the overall development of the country.

The government is currently undergoing a series of reforms to improve irrigation and mechanization. Recently, a historic tax reform bill that removed almost all duty tax on irrigation mechanization technologies was signed by the Ethiopian ministry of finance (MoF) in May of 2019 (ATA 2019; Signs 2019). This is a huge opportunity to improve the largely traditional, inefficient, and non-equipped irrigation system of the country, as irrigation machinery, would become reasonably cheaper and accessible to farmers. However, even with the tax reform bill removing all taxes on irrigation machinery, farmers still find it hard to afford them. Thus, the government should provide a long-term, interest-free loan to farmers to help ease access to machinery and mechanizing the irrigation system gradually.

Various international organizations, NGOs and other interested funders are actively engaged in funding irrigation development programs in the country. The World Bank is providing funds to help improve irrigation usage and increase the supply of resources to benefit 1.6 million smallholder farmers in Ethiopia through the agricultural growth program II (AGPII) (Borgen-project 2021). A Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded project, prioritizing on climate-smart water management practices, is currently being undertaken by IWMI in Ethiopia (IWMI). The project aims at identifying improved water management decision support tools and enhancing climate change adaptation practices for SSP through improved AWM technologies. These and many other funding entities are currently in the country providing funds for the development of the country’s agriculture in general and the improvement of the irrigation sectors in particular. These funding entities are huge opportunities, as they are forces for good pushing the country’s irrigation system towards mechanization and adoption of climate-smart water management techs in this era of rapid climate change.

7. Challenges to Irrigation Development in Ethiopia

The main challenges to irrigation development in Ethiopia are the expensive setup and operating costs of irrigation facilities. The prolonged time spent on the management of irrigated crop farms is reported to be double compared to the less management-demanding and less costly rain-fed farming (Eneyew et al. 2014). Though this scenario is known to create employment and generate more pay rates for laborers, it tends to make the operational cost unaffordable for the farmers (Borgen-project 2021). Such poor financial capital of the farmers holds them back from getting their hands on improved irrigation technologies and paying for the increased operational costs. Moreover, inadequate extension services coupled with lack of adequate information on agricultural water management system gets in the way of modernizing the mostly traditional irrigation system of the country (MOA 2011).

The other challenge hindering the development of irrigation and often leading to the profligate use of water is the absence of strong irrigation water management institutions at various levels. There exist only two types of irrigation institutions in the country, irrigation water users associations (IWUA) and irrigation cooperatives/committees. These two govern only 70% of the irrigation schemes, leaving the remaining 30% of the schemes unmanaged (Haileslassie et al. 2016). It was also revealed that the average membership of semi-modern and modern scheme irrigation users in the irrigation water association is 70% lesser than that of smallholder irrigation users. This is a colossal problem as it hinders the applicability of irrigation water use rules and paves a way for free usage of irrigation water by non-members. This creates a sense of inequity among members usually leading to frequent conflicts. Up to 46% of farmers in parts of Ethiopia reported frequent water-related conflicts caused mainly by irrigation water theft and turn abuse in their irrigation schemes (Belay and Bewket 2013). Therefore, Effective water management strategies are important as water is a very scarce resource and should be conserved. This gets even more alarming when realizing that crop water demand is going to drastically increase for most of the crop plants and precipitation will follow a trend of decline or high variability in most parts of the world in this era of rapid climate change (Neilsen et al. 2002; Parekh and Prajapati 2013).

Though things on the ground are bettering off currently, the ongoing civil war and civil unrest have significantly affected the country’s agriculture since its breakout in 2020. This has left a great deal of land uncultivated and led million to acute starvation, especially in northern parts of Ethiopia. According to FAO, the war has severely disrupted agricultural operations in Tigray and neighboring areas of the Amhara and Afar regions (FAO 2021b). The Tigray agricultural bureau revealed that an estimated 1.3 million ha of crops were damaged in the Tigray regional state due to the destruction of land and plundering as a result of the war (FAO 2021a; FAO 2021b). Agricultural research activities have also almost ceased in the region as the Tigray agricultural research institute sustained massive damage to its research facilities and irrigation systems as a result of the war (Gebremedhin 2020). A lot of damage to crop produce has also been encountered in north Shewa of the Amhara region as many farmers couldn't harvest their crops due to the interruption by the civil war (Gerth-Niculescu 2021). Therefore, Prevalence of peace and stability would be vital for agricultural activity to return to normal and feed the millions of people starving in the northern parts of Ethiopia, Tigray, Afar, and Amhara as well as the rest of the country.

There also have been civil unrest almost all over the country including Oromia, Benishangul, and the southern nations nationalities and peoples regional states, which has worsened agricultural production status. Hence, it’s not uncommon to observe a decline in the irrigated production area or the number of farmers involved in irrigation in the past few years. However, neither food insecurity nor poverty cares about war. Meaning no matter the reason behind it, people will get hungry and suffer from poverty as long as there is not enough production and income. It’s not like food insecurity and poverty are going to offer people a pass on hunger and malnourishment with a sentiment that they are affected by war or any other excuse for that matter. The only way toward food security and prosperity, hence the realization of the SDG is by sustainably increasing production and income surfing against all odds.

8. Conclusions and Prospects

Ethiopia is blessed with a huge irrigtion potential and varying agroecology suitable to produce almost every type of food crops. Regardless, a great deal of the population of the country suffers from acute hunger and severe poverty, as result of failure to exploit this great irrigation potential. Although the government has given a very serious focus to the irrigation sector in recent years, there still is a long way to go in designing and implementing irrigation development strategies. Therefore, a strong commitment is needed to take advantage of the various benefits of irrigation, ranging from ensuring food security to fostering the house hold and the national economy.

When the Ethiopian government plans to use irrigation as a tool foor famine allevaiation works should focus on dealing with each of the componenets of food security. This would be very important as it helps to identify which dimension of food security the country or the community under consideration is lacking. Indentification of the exact weak food security link would enable the policy makers to come up with immidiate short and long term plans to fix it and ensure food secutity. Other wise, the government for instance would be working towards food avaialibity, when the actual cuase of the food insecurity in the country is lack of acess to or poor utilization of the available food.

The same goes for when the government intends to improve both household and national economy through irrigation. The government should first assese the major possible ways irrigation could help improve the economy and deal with them indivisually. Therefore the focus should be on how to use the irrigation sector to create more better paying jobs, boost household incomes, overcome the various poverty indices, improve the GDP and make all this to work for the good of the overall national economy.

Systematic studies aimed at the determination of a quantified and direct contribution of irrigation in poverty reduction, food security, as well as the overall national economy and the SDG should be intensified. This is crucial as it serves as a more precise tool in measuring the progress of the irrigation sector in relation to poverty and hunger alleviation and helps to design and implement intervention methods.

Disclosure Statement

All authors declare that there exist no commercial or financial relationships that could, in any way, lead to a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abdissa, F., Tesema, G., & Yirga, C. (2017). Impact analysis of small scale irrigation schemes on household food security the case of Sibu Sire District in Western Oromia, Ethiopia. Irrigat Drainage Sys Eng, 6(187),2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9768.1000187. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A. (2017). The determinants of small-scale irrigation practice and its contribution on household farm income: The case of Arba Minch Zuria Woreda, Southern Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 12(13),1136-1143. DOI: 10.5897/ajar2016.11739. [CrossRef]

- Adenew, B. (2004). The food security role of agriculture in Ethiopia. J. Dev. Agric. Econ., 1(1),138-153.

- Adu, M.O., Yawson, D.O., Armah, F.A., Asare, P.A., & Frimpong, K.A. (2018). Meta-analysis of crop yields of full, deficit, and partial root-zone drying irrigation. Agricultural Water Management, 197,79-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2017.11.019. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J. (2019). The role of small scale irrigation to household food security in Ethiopia: a review paper. J. Res. Dev. and Manag., 60,20-25. https://doi.org/10.7176/jrdm/60-03. [CrossRef]

- Aljazeera (2020) Ethiopian forces fire at UN team as aid groups seek Tigray access Rretrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/12/8/warnings-intensify-as-badly-needed-aid-still-not-reaching-tigray.

- AP-news (2021) Ethiopia accuses aid groups of ‘arming’ Tigray fighters Rretrieved from https://apnews.com/article/africa-ethiopia-cc5d22460b7990a48796b23cf8525285.

- Asrat, D., Anteneh, A., Adem, M., & Berhanie, Z. (2022). Impact of Awash irrigation on the welfare of smallholder farmers in Eastern Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Finance, 10(1),2024722. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.2024722. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, E., Ayalew, Z., & Mohammed, H. (2022). Impact of small-scale irrigation schemes on farmers livelihood, the case of Mekdela Woreda, North-East Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1),2041259. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2041259. [CrossRef]

- Astatike, A.A. (2016). Assessing the impact of small-scale irrigation schemes on household income in Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda, Ethiopia. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev, 7,82-88.

- ATA (2019) MoF approves tax-free imports of agricultural mechanization, irrigation and animal feed technologies Rretrieved from http://www.ata.gov.et/mof-approves-tax-free-imports/.

- ATA (2021) Agricultural transformation agency annual report. Rretrieved from http://www.ata.gov.et/download/annual-report-transforming-agriculture-in-ethiopia/.

- Awulachew, S., Erkossa, T., & Namara, R. (2010) Irrigation potential in Ethiopia–constraints and opportunities for enhancing the system. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.: IWMI.

- Awulachew, S.B., & Ayana, M. (2011). Performance of irrigation: An assessment at different scales in Ethiopia. Experimental Agriculture, 47(1),57-69. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0014479710000955. [CrossRef]

- Awulachew, S.B., Merrey, D., Kamara, A., van Koppen, B., Penning de Vries, F., & Boelee, E. (2005) Experiences and opportunities for promoting small-scale/micro irrigation and rainwater harvesting for food security in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.: IWMI.

- Awulachew, S.B., Yilma, A.D., Loulseged, M., Loiskandl, W., Ayana, M., & Alamirew, T. (2007) Water resources and irrigation development in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: IWMI.

- Ayinu, Y.T., Ayal, D.Y., Zeleke, T.T., & Beketie, K.T. (2022). Impact of climate variability on household food security in Godere District, Gambella Region, Ethiopia. Climate Services, 27,100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2022.100307. [CrossRef]

- Bacha, D., Namara, R., Bogale, A., & Tesfaye, A. (2011). Impact of small-scale irrigation on household poverty: empirical evidence from the Ambo district in Ethiopia. Irrig. and Drain., 60(1),1-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.550. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B., & Lentz, E.C. (2010) Food insecurity, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies.

- Baye, K., Mekonnen, D., Choufani, J., Yimam, S., Bryan, E., Grifith, J.K., et al. (2021). Seasonal variation in maternal dietary diversity is reduced by small-scale irrigation practices: A longitudinal study. Matern Child Nutr., 18(2),e13297. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13297. [CrossRef]

- Belay, M., & Bewket, W. (2013). Traditional irrigation and water management practices in highland Ethiopia: Case study in Dangila woreda. Irrig. and Drain., 62(4),435-448. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.1748. [CrossRef]

- Borgen-project (2021) Smallholder farmers in Ethiopia Rretrieved from https://borgenproject.org/tag/smallholder-farmers-in-ethiopia.

- Chai, Q., Gan, Y., Zhao, C., Xu, H.-L., Waskom, R.M., Niu, Y., et al. (2016). Regulated deficit irrigation for crop production under drought stress. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development, 36,1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0338-6. [CrossRef]

- Dawit, M., Dinka, M.O., & Leta, O.T. (2020). Implications of adopting drip irrigation system on crop yield and gender-sensitive issues: The case of Haramaya District, Ethiopia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4),96. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040096. [CrossRef]

- Eneyew, A., Alemu, E., Ayana, M., & Dananto, M. (2014). The role of small scale irrigation in poverty reduction. J. Dev. Agric. Econ., 6(1),12-21. DOI: 10.5897/JDAE2013.0499. [CrossRef]

- ESC (2019a) Ethiopian Sugar Industry Profile Rretrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/meresaf/ethiopian-sugar-industry-profile-166554323.

- ESC (2019b) Wonji Shoa Sugar Facory Rretrieved from https://etsugar.com/wonji-shoa-sugar-facory/.

- Eshetu, T., & Young-Bohk, C. (2017). Contribution of Small Scale Irrigation to Households’ Income and Food Security: Evidence from Ketar Irrigation Scheme, Arsi Zone, Oromiya Region, Ethiopia. African Journal of Business Management, 11(3),57-68. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2016.8175. [CrossRef]

- ESS. (2021) Agricultural sample survey 2020/21(2013 e.c.);report on farm management practices (private peasant holdings, meher season), Ethiopian statistical service, Addis Ababa.

- Fantini, E., Muluneh, T., & Smit, H. (2018) Big projects, strong states?: Large-scale investments in irrigation and state formation in the Beles Valley, Ethiopia, Water, technology and the nation-state, Routledge. pp. 65-80.

- FAO (2016) AQUASTAT Country Profile – Ethiopia Rretrieved from https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/countries-and-basins/country-profiles/country/ETH.

- FAO (2021a) Emergencies in Ethiopia. Rretrieved from https://www.fao.org/emergencies/countries/detail/en/c/151593.

- FAO (2021b) Emergency livelihood support for conflict-affected communities in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Rretrieved from https://www.fao.org/emergencies/fao-in-action/stories/stories-detail/en/c/1415016/.

- FAO (2022) Ethiopia at a glance Rretrieved from https://www.fao.org/ethiopia/fao-in-ethiopia/ethiopia-at-a-glance/en/.

- Fews-net (2022) Food Assistance Outlook Brief, November 2022 Rretrieved from https://fews.net/global/food-assistance-outlook-brief/november-2022.

- Gebregziabher, G., Namara, R.E., & Holden, S. (2009). Poverty reduction with irrigation investment: An empirical case study from Tigray, Ethiopia. Agricultural water management, 96(12),1837-1843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2009.08.004. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, K.G., Makina, D., & Woldu, T. (2017). The impact of micro-irrigation on households’ welfare in the northern part of Ethiopia: an endogenous switching regression approach. Studies in agricultural economics, 119(3),160-167. https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1707. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, N.T., Mesfin, K.A., & Nyssen, J. (2015). Small-scale irrigation: the driver for promoting agricultural production and food security (the case of Tigray Regional State, Northern Ethiopia). Irrig. drain. syst. eng., 4(2),1000141. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9768.1000141. [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, B. (2020) In Tigray Even Research Institutions Are Not Spared: The Plight of Tigray Agricultural Research Institute Rretrieved from https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2022/03/01/tigray-the-destruction-of-invaluable-agricultural-research/#_ftn1.

- Gerth-Niculescu, M. (2021) Ethiopia's Amhara region shattered after weeks of war Rretrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopias-amhara-region-shattered-after-weeks-of-war/a-60145364.

- Getaneh, Y., Alemu, A., Ganewo, Z., & Haile, A. (2022). Food security status and determinants in North-Eastern rift valley of Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 8,100290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100290. [CrossRef]

- GHI (2022) Global hunger index 2022; Ethiopia Rretrieved from https://www.globalhungerindex.org/ethiopia.html.

- Gross, R., Schoeneberger, H., Pfeifer, H., & Preuss, H.-J. (2000). The four dimensions of food and nutrition security: definitions and concepts. SCN News, 20(20),20-25.

- Hagos, F., Jayasinghe, G., Awulachew, S.B., Loulseged, M., & Yilma, A.D. (2012). Agricultural water management and poverty in Ethiopia. Agric Econ., 43,99-111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2012.00623.x. [CrossRef]

- Hagos, F., Makombe, G., Namara, R.E., & Awulachew, S.B. (2009) Importance of irrigated agriculture to the Ethiopian economy: Capturing the direct net benefits of irrigation. Addis ababa,Ethiopia: IWMI. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejdr.v32i1.68597. [CrossRef]

- Haileslassie, A., Hagos, F., Agide, Z., Tesema, E., Hoekstra, D., & Langan, S.J. (2016) Institutions for irrigation water management in Ethiopia: Assessing diversity and service delivery. Nairobi, Kenya.: ILRI.

- Hussain, I., & Hanjra, M.A. (2004). Irrigation and poverty alleviation: review of the empirical evidence. Irrig. and Drain., 53(1),1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.114. [CrossRef]

- IWMI Prioritization of climate-smart water management in Ethiopia. Rretrieved from https://www.iwmi.cgiar.org/what-we-do/projects/show-projects/.

- Jambo, Y., Alemu, A., & Tasew, W. (2021). Impact of small-scale irrigation on household food security: evidence from Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur., 10(1),1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00294-w. [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S., & Molla, D. (1995) Toward a research agenda to promote household access to food in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: MEDC.

- Jebessa, G.M., Sima, A.D., & Wondimagegnehu, B.A. (2019). Determinants of household dietary diversity in Yayu Biosphere Reserve, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop. j. sci. technol., 12(1),45-68. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejst.v12i1.3. [CrossRef]

- Jerving, S. (2022) A week after Tigray truce, aid sector still unable to deliver food Rretrieved from https://www.devex.com/news/a-week-after-tigray-truce-aid-sector-still-unable-to-deliver-food-102970.

- Kelilo, A., Ketema, M., & Kedir, A. (2014). The Contribution of Small Scale Irrigation Water Use to Households Food Security in Gorogutu District of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. IJEER, 2(6),221-228.

- Kim, S., Meki, M.N., Kim, S., & Kiniry, J.R. (2020). Crop modeling application to improve irrigation efficiency in year-round vegetable production in the Texas winter garden region. Agronomy, 10(10),1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10101525. [CrossRef]

- Knaome (2019) Ethiopia - Irrigation potential Rretrieved from https://knoema.com/atlas/Ethiopia/topics/Water/Irrigation-Water-Management/Irrigation-potential.

- Kyei-Mensah, C., Kyerematen, R., & Adu-Acheampong, S. (2019). Impact of rainfall variability on crop production within the Worobong Ecological Area of Fanteakwa District, Ghana. Advances in Agriculture, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7930127. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, J.L., Ruel, M., Frongillo, E.A., Harris, J., & Ballard, T.J. (2015). Measuring the food access dimension of food security: a critical review and mapping of indicators. Food Nutr Bull., 36(2),167-195.

- Lewis, K. (2017). Understanding climate as a driver of food insecurity in Ethiopia. Climatic Change, 144,317-328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2036-7. [CrossRef]

- LI (2022) Irrigation potential Definition Rretrieved from https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/irrigation-potential.

- Li, J., Ma, W., Renwick, A., & Zheng, H. (2020). The impact of access to irrigation on rural incomes and diversification: evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev., 12(4),705-725. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-09-2019-0172. [CrossRef]

- Mashnik, D., Jacobus, H., Barghouth, A., Wang, E.J., Blanchard, J., & Shelby, R. (2017). Increasing productivity through irrigation: Problems and solutions implemented in Africa and Asia. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 22,220-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2017.02.005. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, D.K., Choufani, J., Bryan, E., Haile, B., & Ringler, C. (2022). Irrigation improves weight-for-height z-scores of children under five, and Women's and Household Dietary Diversity Scores in Ethiopia and Tanzania. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18(4),e13395. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13395. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, G.S. (2017). Food security status of peri-urban modern small scale irrigation project beneficiary female headed households in Kobo Town, Ethiopia. Journal of Food Security, 5(6),259-272. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfs-5-6-6. [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, D., & Kidane, D. (2016). Assessment of the impact of small-scale irrigation on household livelihood improvement at Gubalafto District, North Wollo, Ethiopia. Agriculture, 6(3),27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture6030027. [CrossRef]

- MOA. (2011) Small-scale irrigation capacity-building strategy for Ethiopia Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp. 1-30.

- Mohamed, A.A. (2017). Food security situation in Ethiopia: a review study. International journal of health economics and policy, 2(3),86-96. doi: 10.11648/j.hep.20170203.11.

- Muleta, G., Ketema, M., & Ahmed, B. (2021). Impact of small-scale irrigation on household food security in central highlands of ethiopia: evidences from Walmara District. J Econ Sustain Dev, 12(3),31-37.

- Muluneh, A., Stroosnijder, L., Keesstra, S., & Biazin, B. (2017). Adapting to climate change for food security in the Rift Valley dry lands of Ethiopia: supplemental irrigation, plant density and sowing date. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 155(5),703-724. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021859616000897. [CrossRef]

- Nakawuka, P., Langan, S., Schmitter, P., & Barron, J. (2018). A review of trends, constraints and opportunities of smallholder irrigation in East Africa. Global food security, 17,196-212. doi:10.1016/J.GFS.2017.10.003. [CrossRef]

- Neilsen, D., Smith, C., Frank, G., Koch, W., & Parchomchuk, P. (2002) Impact of climate change on crop water demand in the Okanagan Valley, BC, Canada, XXVI International Horticultural Congress: Sustainability of Horticultural Systems in the 21st Century 638. pp. 273-278. Doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2004.638.36. [CrossRef]

- Nigussie, A., Adisu, A., Desalegn, K., & Gebreegziabher, A. (2016). Agricultural extension for enhancing productivity and poverty alleviation in small scale irrigation agriculture for sustainable development in Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 11(3),171-183. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2015.9541. [CrossRef]

- Nugusse, Z.W. (2012) Food Security through Small Scale Irrigation: Case Study from Northern Ethiopia, Rural Developeement, Ghent University, Brussels, Belgium. pp. 65.

- Ogunniyi, A., Omonona, B., Abioye, O., & Olagunju, K. (2018). Impact of irrigation technology use on crop yield, crop income and household food security in Nigeria: A treatment effect approach. AIMS Agric. Food., 3,154-171. https://doi.org/10.3934/agrfood.2018.2.154. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, F., & Prajapati, K.P. (2013). Climate change impacts on crop water requirement for Sukhi reservoir project. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol, 2(9),2-10.

- Passarelli, S., Mekonnen, D., Bryan, E., & Ringler, C. (2018). Evaluating the pathways from small-scale irrigation to dietary diversity: evidence from Ethiopia and Tanzania. Food Security, 10(4),981-997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0812-5. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K., & Kołodziejczak, M. (2020). The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: Considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability, 12(13),5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135488. [CrossRef]

- Paynter, S., Berner, M., & Anderson, E. (2011). When even the'dollar value meal'costs too much: Food insecurity and long term dependence on food pantry assistance. Public Administration Quarterly,26-58.

- Reddy, K.M., Satyanarayana, T., Babu, G.R., & Babu, M.R. (2017). Estimation of Irrigation Potential Utilization for Kanupur Canal System Using Remote Sensing and GIS. The Andhra Agric. J., 64,402-425.

- Reliefweb (2022) Ethiopia Food Security Alert. Rretrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-food-security-alert-may-27-2022.

- Reuters (2020) Aid groups unable to supply Ethiopia's Tigray region, UN warns Rretrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/12/aid-groups-unable-to-supply-ethiopias-tigray-region-un-warns.

- Sani, S., & Kemaw, B. (2019). Analysis of households food insecurity and its coping mechanisms in Western Ethiopia. Agricultural and food economics, 7(1),1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-019-0124-x. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N., Maqsood, M., Mubeen, K., Shehzad, M., Bhullar, M., Qamar, R., et al. (2010). Effect of different levels of irrigation on yield and yield components of wheat cultivars. Pak. J. Agri. Sci, 47(3),371-374.

- Sekyi-Annan, E., Tischbein, B., Diekkrüger, B., & Khamzina, A. (2018). Year-round irrigation schedule for a tomato–maize rotation system in reservoir-based irrigation schemes in Ghana. Water, 10(5),624. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050624. [CrossRef]

- Signs, M. (2019) Making irrigation technology more affordable in Ethiopia Rretrieved from https://wle.cgiar.org/news/making-irrigation-technology-more-affordable-ethiopia.

- Simon, G.-A. (2012) Food Security: Definition, Four Dimensions, History: Basic Readings as an Introduction to Food Security for Students from the IPAD Master, SupAgro, Montpellier Attending a Joint Training Programme in Rome, Rome, IT: University of Roma pp. 1-28.

- Sithole, N.L., Lagat, J.K., & Masuku, M.B. (2014). Factors influencing farmers participation in smallholderirrigation schemes: The case of ntfonjeni rural development area. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(22),157-167.

- Tedros, T. (2014) Contribution of Small Holders’ Irrigation to Households Income and Food Security: A Case Study of Gum-selasa and Shilena Irrigation Schemes, Hintalowejerat, South-Estern Zone of Tigray, Ethiopia.

- Tefera, E., & Cho, Y.-B. (2017). Contribution of small scale irrigation to households income and food security: evidence from Ketar irrigation scheme, Arsi Zone, Oromiya Region, Ethiopia. African Journal of Business Management, 11(3),57-68.

- Temesgen, T., Ayana, M., & Bedadi, B. (2018). Evaluating the effects of deficit irrigation on yield and water productivity of furrow irrigated onion (Allium cepa L.) in Ambo, Western Ethiopia. Irrigation & Drainage Systems Engineering, 7(1),1-6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9768.1000203. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A., Bogale, A., Namara, R.E., & Bacha, D. (2008). The impact of small-scale irrigation on household food security: The case of Filtino and Godino irrigation schemes in Ethiopia. Irrig Drainage Syst., 22(2),145-158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10795-008-9047-5. [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, H., Teklu, E., Michael, M., Fitsum, H., & Awulachew, S.B. (2011). Comparative performance of irrigated and rainfed agriculture in Ethiopia. World Appl Sci J., 14(2),235-244.

- Tsegay, A., Vanuytrecht, E., Abrha, B., Deckers, J., Gebrehiwot, K., & Raes, D. (2015). Sowing and irrigation strategies for improving rainfed tef (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter) production in the water scarce Tigray region, Ethiopia. Agricultural Water Management, 150,81-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2014.11.014. [CrossRef]

- UNDP. (2018a) Ethiopia’s Progress Towards Eradicating Poverty, Implementation of the Third United Nations Decade for the Eradication of Poverty (2018 – 2027), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp. 1-9.

- UNDP. (2018b). Ethiopia’s Progress Towards Eradicating Poverty, Paper to presented to the Inter-Agency Group Meeting On the “Implementation of the Third United Nations Decade for the Eradication of Poverty (2018–2027)” Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Also available at https://www. un. org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2018/04/Ethiopia% E2, 80.

- USAID (2022) Agriculture and food security In Ethiopia Rretrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/ethiopia/agriculture-and-food-security.

- Van Den Berg, M., & Ruben, R. (2006). Small-scale irrigation and income distribution in Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(5),868-880. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600742142. [CrossRef]

- Wale, A., Sebnie, W., Girmay, G., & Beza, G. (2019). Evaluation of the potentials of supplementary irrigation for improvement of sorghum yield in Wag-Himra, North Eastern, Amhara, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1),1664203. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1664203. [CrossRef]

- Wana, F., & Senapathy, M. (2022). Small-scale Irrigation Utilization by Farmers in Southern Ethiopia: monograph. Primedia eLaunch LLC,174-174.

- WFP (2022) Millions face hunger as drought grips Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia, warns World Food Programme Rretrieved from https://www.wfp.org/stories/millions-face-hunger-drought-grips-ethiopia-kenya-and-somalia-warns-world-food-programme.

- Yimere, A., & Assefa, E. (2021). Assessing and mapping irrigation potential in the abbay river basin, Ethiopia. Russ. j. agric. soc.-econ. sci., 114,97-109. https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2021-06.11. [CrossRef]

- You, L., Ringler, C., Wood-Sichra, U., Robertson, R., Wood, S., Zhu, T., et al. (2011). What is the irrigation potential for Africa? A combined biophysical and socioeconomic approach. Food Policy, 36(6),770-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2011.09.001. [CrossRef]

- Zemarku, Z., Abrham, M., Bojago, E., & Dado, T.B. (2022). Determinants of Small-Scale Irrigation Use for Poverty Reduction: The Case of Offa Woreda, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4049868. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).