1. Introduction

According to (Norisnita & Indrianti, 2022), cryptocurrency is a set of cryptographic codes that can be stored, transferred, and used as a form of payment using block chain technology, which is essentially a digital distributed ledger that records every transaction and stores data in real time. The presence of cryptocurrency raises both benefits and drawbacks in society. Nonetheless, the number of cryptocurrency users has increased. According to a Triple A survey, there will be approximately 320 million cryptocurrency owners in the world by 2022 (TripleA, 2022). Bitcoin, the world's first cryptocurrency, has also seen an increase in value; prior to 2010, one Bitcoin was only worth $ 0.08 or Rp. 1.187,00 (Echchabi & Aziz, et al., 2021). Meanwhile, as of September 7, 2022, one Bitcoin is worth $ 19,417, or Rp. 288 million, according to Coinmarketcap (the value will vary every hour). Because of the high returns obtained in a short period of time, some people are beginning to consider cryptocurrencies as a viable investment asset.

Each investment must involve some level of risk. Risk and return are directly proportional. This is often referred to as high risk, high reward. The principle of "high risk, high return" also applies to investing in crypto assets. Crypto assets are regarded as an investment option that can provide very high returns while also posing a high risk in a short period of time. This is supported by several characteristics of crypto assets, including the absence of underlying assets and the supply and demand principle, which causes extreme volatility in crypto asset values. Many countries are still debating the use of crypto assets in their countries because if used as a means of payment, it can disrupt a country's economic stability. Meanwhile, if it becomes an investment asset, it may cause significant losses for its users.

Since 2013, crypto has gained popularity in Indonesia. Since its inception, Bank Indonesia and the Financial Services Authority (OJK) have been vocally opposed to the use of crypto in Indonesia. According to Bank Indonesia, the use of crypto as a means of payment contradicts Article 1 points (1) and (2) of Law Number 7 of 2011, which states that the Rupiah is the only state currency and legal tender in Indonesia. The currency of a country represents its fundamentals because it describes the country's identity and state sovereignty. Country currencies can distinguish between countries. Because crypto is not issued by a country, it violates existing laws. Bank Indonesia is concerned that the use of crypto in Indonesia will undermine a country's fundamental concepts and disrupt the stability of its currency. Bank Indonesia raised concerns about the crypto system, which wasn't overseen by official authorities or administrators. According to Bank Indonesia, the lack of authority for a digital transaction can increase the prevalence of illegal acts in Indonesia, such as fraud, money laundering, and terrorism financing. In letter Number 20/4DKom, Bank Indonesia emphasized that crypto is not recognized as legal currency because ownership is extremely risky. In 2018, the Coordinating Minister for the Economy issued Letter S-302/M.EKON/09/2018, which defined crypto as a commodity asset that could be the subject of a futures contract that could be traded on a futures exchange under the supervision of the Commodity Futures Trading Regulatory Agency (Bappebti). Because crypto assets are considered physical assets in Indonesia, they are referred to as crypto assets rather than cryptocurrency. The goal of this regulation is to provide legal protection for crypto asset owners while also regulating crypto asset traders in Indonesia.

Bank Indonesia raised concerns about the crypto system, which wasn't overseen by official authorities or administrators. According to Bank Indonesia, the lack of authority for a digital transaction can increase the prevalence of illegal acts in Indonesia, such as fraud, money laundering, and terrorism financing. In letter Number 20/4DKom, Bank Indonesia emphasized that crypto is not recognized as legal currency because ownership is extremely risky. In 2018, the Coordinating Minister for the Economy issued Letter S-302/M.EKON/09/2018, which defined crypto as a commodity asset that could be the subject of a futures contract that could be traded on a futures exchange under the supervision of the Commodity Futures Trading Regulatory Agency (Bappebti). Because crypto is considered physical assets in Indonesia, they are referred to as crypto assets rather than cryptocurrency. The goal of this regulation is to provide legal protection for crypto asset owners while also regulating crypto asset traders in Indonesia. According to a survey conducted by Tokenomy and Indodax for the year 2021 and completed by 21052 people, the majority of crypto assets in Indonesia are owned by people aged 20 to 35. According to the survey, the owners of crypto assets in Indonesia are dominated by young people, the majority of whom are men. In terms of crypto adoption in 2021, Indonesia is ranked fifth in Southeast Asia, trailing Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, and the Philippines (Chainalysis, 2022; Trinugraheni, 2022)

This rapid expansion has OJK concerned. Enrico Hariantoro, Head of the Financial Services Authority's (OJK) Integrated Financial Services Sector Policy Group, questions the literacy of Indonesian crypto asset owners (Pratomo, 2022). Enrico explained that the rapid growth of crypto assets owner should be accompanied by a good understanding of the benefits, costs, and risks of these assets, but according to OJK data, financial literacy among Indonesians remains low, so he believes that Indonesians are not ready to accept crypto (Pratomo, 2022). According to the results of the OJK survey from 2019 to 2022, the level of financial literacy among Indonesians increased from 38.03% to 49.68%. Even though there has been an increase, the OJK considers this figure to be too low to say that Indonesians are ready to accept the presence of crypto assets. According to OJK, the general public is still unfamiliar with how to manage their finances and the characteristics of the various products and services available. As a result, the government is particularly concerned about the rapid growth of crypto asset owners in Indonesia.

The government is also skeptical of the factors that lead to an interest in crypto assets. (Jalan et al., 2022) concerns about the security of transactions based solely on cryptographic encryption and block chain technology in the absence of a responsible state authority that can persuade people to use cryptocurrency. According to (A. Wijaya et al., 2021), crypto assets investors' current trust is not in the system but in exchanges. Based on this, more research on public trust in the block chain system and exchanges in Indonesia is required.

The presence of crypto assets in Indonesia has piqued the interest of many people. This new technology has been covered extensively in the media and on social media. Crypto traders introduce crypto assets to the public through informative, light, and easy-to-understand content, the selection of good key people, and the right target market. They want to raise public awareness about crypto assets and the benefits of investing in them. The prospect of making large profits in a short period of time by investing in crypto assets makes this investment appealing. This places social pressure on potential users to invest in crypto assets right away. A person's perception of social pressure, or subjective norms, to have certain behavioral intentions is a factor that must be considered when determining the increasing growth of crypto asset owners in Indonesia.

Based on this explanation, additional research into the factors that cause the emergence of the intention to invest in crypto assets due to the rapid growth of crypto asset owners in Indonesia is required. The novel aspect of this study is the incorporation of subjective norms from the Theory of Planned Behavior with financial literacy, trust, and government regulations, as well as the use of gender as a moderator between exogenous and endogenous variables.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crypto Assets

According to Harwick, as cited by Rice, cryptocurrency is defined as a virtual asset that is used as a form of digital currency that is exchanged by transferring assets and other forms of financial instruments (Rice, 2019). According to DuPont, as cited by Pham et al., cryptocurrency can operate using a technology known as block chain (Pham, Phan, Cristofaro, & Misra, 2021). (Park & Park, 2019) explains that cryptocurrency is not controlled by the government or the banking system of financial institutions. Based on this definition, cryptocurrency is an encrypted virtual asset that uses block chain technology and can be used as digital currency.

Cryptocurrency is banned in Indonesia but can be used as an investment asset (crypto asset). Crypto assets are considered physical assets rather than financial assets because they meet the material requirements of Article 499 on Objects. First, crypto is considered a physical asset like gold because it is intangible and can move. Crypto assets are intangible because they are digital data with value and property rights. Crypto assets can be transferred electronically via the internet from one digital wallet to another by the asset's owner, making them movable (Wijaya, 2019). Crypto, which has economic value, is digitally owned and can be moved directly by the owner, making it a digital asset (Franco, 2015). Crypto assets can be used for money transfers, exchange trading, and investment commodities as digital assets. In commodity futures trading, crypto is a commodity since Regulation of the Minister of Trade of the Republic of Indonesia No. 99 of 2018 concerning Crypto Asset Trading.

2.2. Investment Theory

Investment is a commitment to postpone or sacrifice funds or resources currently owned and divert them to productive assets or production processes in hopes of future profits (Hasani, 2022; Huda & Hambali, 2020; Laopodis, 2020). Society views investment as a desire and a need. If someone has excess funds but doesn't invest them, it's a desire (Tandio & Widanaputra, 2016). If a person uses excess funds for investment rather than savings, investment is necessary. This shows that from the start the person intended to invest (Tandio & Widanaputra, 2016). Investments involve risks due to their uncertainty. Risk and return expectations are linear and unidirectional, so if an investment's risk is low, it won't return much (Mardhiyah, 2017). Tandelilin, as quoted by Mardhiyah, divides returns into two categories: expected returns and realized returns (actual returns that occur) (Mardhiyah, 2017). The risk in investing exists when there is a value difference between the expected return and the realized return. The greater the gap between the two, the greater the danger. This distinction must be taken into account by all investors.

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

According to Dr. Icek Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior, three beliefs—behavioral, normative, and control—control human behavior (Yadav & Pathak, 2017). This development stems from the idea that expectations or beliefs about an object's attributes or actions and their evaluation determine attitudes toward it. TPB states that behavioral beliefs affect attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms affect subjective norms, and control beliefs affect perceived behavioral control (Islam et al., 2022; Yadav & Pathak, 2017). Attitude influences behavior because the desire to adopt a behavior is based on a belief in its expected outcomes (Syarkani & Tristanto, 2022; Tseng et al., 2022). Subjective norms influence behavior due to individuals' normative beliefs in response to perceived group pressure that influences certain behaviors (Khan et al., 2019; Tseng et al., 2022). Perceived behavioral control influences behavior because of beliefs regarding the existence of factors that facilitate or inhibit a behavior, making it easy or difficult to perform (Ajzen, 2020).

According to previous research (Huong et al., 2021), only the subjective norm variable of the three TPB variables used to determine the intention to invest in crypto assets in Vietnam influences a person's intention to invest in crypto assets. According to (Anggraini, 2021), TPB has a weakness in that its scope is limited to individual rational behavior, despite the fact that human emotions frequently influence behavior. This theory does not explain human behavior in terms of their emotions (Zhang, 2018). TPB is deemed suitable for determining the factors that influence behavioral intentions to invest in cryptocurrencies.

2.4. Financial Literacy

(Zhao & Zhang, 2021) defines financial literacy as the extent to which a person understands the main concepts of finance so that he can confidently manage personal finances by making short-term financial decisions and planning long-term finances. Financial literacy is also the ability to use financial resource management skills for lifelong financial stability (Jariyapan et al., 2022). According to (Zhao & Zhang, 2021), financial literacy has two dimensions: objective and subjective financial knowledge. Subjective financial knowledge is an individual's belief in their financial knowledge, while objective finance is their understanding of financial concepts, principles, and instruments. According to Lusardi and Mitchell, quoted from Salisa, having good financial literacy will prevent people from making bad financial decisions because it means they understand various investment instruments and can manage investments wisely (Salisa, 2020).

Crypto assets are a new investment instrument in Indonesia. Before selecting the appropriate crypto assets for investment, one must possess a sufficient level of financial literacy. Given the high risk, it is necessary to determine an individual's intention to invest in crypto assets by determining their financial literacy level.

2.5. Trust

Trust is crucial to technology disruption, according to Kethineni and Yao, cited by Koroma et al (Koroma et al., 2022). Trust is crucial when introducing new technology, according to (Tang et al., 2021). Trust affects someone's intention to use it (Mendoza-tello et al., 2018). Trust is a person's willingness to put themselves in a vulnerable position in hopes of a good outcome or good behavior (Kaur & Rampersad, 2018). Trust is a sense of security and guarantees that service providers can provide to increase behavior in using technology, such as crypto asset exchanges(Tang et al., 2021). According to (Alaeddin & Altounjy, 2018), if someone feels confident after using the new technology for the first time, they can continue using it. To increase crypto asset investors, (Rekabder et al., 2021) agreed that trust-based connections are necessary. Trust affects behavioral intention, according to (Ku-mahamud et al., 2019; Rekabder et al., 2021).

(Mendoza-tello et al., 2018) explains that when investing in crypto assets, the cryptographic methods provided by the crypto ecosystem and anonymous transactions can guarantee the confidentiality and security of transactions. Interestingly, in the process of investing in crypto assets, users must rely on the block chain system. (Beck et al., 2016) refer to cryptocurrency investments as "trustless." This investment is undoubtedly distinct from others, necessitating additional research into its trustworthiness.

2.6. Government Regulation

According to (Irma et al., 2021), there are five reasons why strict regulation and oversight of crypto usage in Indonesia are crucial. First, the risk to the payment system and management of Rupiah if crypto assets are used as a payment method, which is contrary to Law no. 7 of 2011, which states that the Indonesian national currency is the rupiah and must be issued by the government. Second, there is the risk of capital outflows, which could have an impact on Bank Indonesia's monetary policy because these funds cannot be used to drive the domestic economy. Third, the risk to the stability of the financial system posed by crypto asset transactions. Cryptocurrency cannot be used as currency due to its volatile value. Risk of violations of the Anti-Money-Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Act (APU-PPT). The central government is suspicious of the anonymity of crypto transactions because it appears to facilitate money laundering, fraud, and even the financing of terrorism. Fifth, the risk of breaching consumer and personal data protection due to the lack of a governing body overseeing the purchase and sale of crypto assets (Perkins, 2020).

In Indonesia, crypto is viewed as an asset and not a currency. Multiple studies have found that government regulations impact the existence of crypto. They discovered that this government regulation influences the price fluctuations of crypto coins (Bhuvana & Aithal, 2022), crypto adoption (Bunjaku et al., 2017), trust (Alaeddin & Altounjy, 2018; Arli et al., 2020), technology acceptance (Anser et al., 2020a), subjective norms (Zamzami, 2020), and behavioral intentions (Mushi, 2020). The effect of government regulation on the intention to invest in crypto assets requires further investigation, given these findings.

2.7. Gender

Gender has been shown to have an effect on behavioral intentions in a variety of sectors, including marketing (Heidarian, 2019), retail (Mosquera et al., 2018), entrepreneurship (Hutasuhut & Article, 2018; Luis et al., 2015), food delivery services (Hwang et al., 2019; Zhai et al., 2022), e-commerce (Marinković et al., 2019), e-wallets (Yang et al., 2021), mobile payments (Cabanillas et al., 2021), etc. (Alshamy, 2019) discovered that a person's investment intent is affected by their gender. (Bannier & Neubert, 2016; Lemaster & Strough, 2013) discovered that gender influences investment intentions due to differences in risk tolerance between men and women. According to (Astika & Sari, 2019), men and women have different investment perspectives. Men tend to choose investments with a higher risk profile, whereas women choose investments with a lower risk profile. According to Bayyurt, cited by Astika & Sari, this is due to the fact that women have less investment confidence than men (Astika & Sari, 2019). According to (Altowairqi et al., 2021) research, men are more aware of the risks associated with investments than women. According to (Marlow & Swail, 2014), men are more likely to enjoy taking risky investment actions than women due to the physiological makeup of men. Based on this explanation, further research is required to determine the effect of gender on the intention to invest in crypto assets.

2.8. Relationship between Subjective Norms and Behavioral Intention

Multiple studies have produced contradictory findings regarding the relationship between subjective norms and behavior intentions. According to (Arias-oliva et al., 2019; Ayedh et al., 2020; Echchabi, Omar, et al., 2021; Mazambani & Mutambara, 2019; Nurbarani & Soepriyanto, 2022; Nurhayani et al., 2022; Zamzami, 2020), subjective norms do not influence an individual's intent to use cryptocurrencies. In contrast, (Almajali et al., 2022; Anser et al., 2020b; Echchabi, Aziz, et al., 2021; Pham, Phan, Cristofaro, Misra, et al., 2021) discovered that subjective norms influence behavioral intentions to use crypto. (Gazali et al., 2019; Jariyapan et al., 2022) state that investors' perceptions of influential and trustworthy individuals have the greatest impact on their decision to invest in crypto.

According to research (Huong et al., 2021) to determine the behavioral intention of investing in crypto assets in Vietnam, subjective norms have a positive and significant impact on the intention to invest in crypto assets. In this study, it has been determined that perceived behavioral control has a negative and statistically significant impact on behavioral intentions, as crypto is not widely accepted by law in many nations due to its technological and intangible nature. Despite the fact that many companies and nations have accepted the presence of crypto, crypto assets are still viewed as too risky by many investors, leading many to believe that crypto assets are difficult to invest in. Consequently, according to the same research, attitude has a weak influence on behavioral intentions because crypto is still in the development stage and is still penetrating the market, which affects a person's attitude because their intention will be influenced by whether crypto is legally accepted in that country. Based on the preceding explanation, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H1 : Subjective Norms have an influence on Behavioral Intentions

2.9. Relationship between Financial Literacy and Behavioral Intention

(Rasool & Ullah, 2020) explains that investors must possess a high level of financial literacy in order to maximize investment choices and opportunities from the various investment products offered. According to them, investment products are complex instruments that necessitate investors' financial literacy. Personal financial problem comprehension, analysis, management, and communication can be interpreted as financial literacy (Rahayu et al., 2022). A person with a high level of financial literacy will seek out risky investments and will be able to make sound investment decisions (Samsuri et al., 2019). The relationship between financial literacy and the intention to invest can be deduced from the preceding explanation, as a person with a high level of financial literacy will be inclined to invest. Those who wish to invest in extremely risky crypto assets must therefore possess a high level of financial literacy. The researcher proposes the following hypothesis based on the preceding explanation:

H2 : Financial Literacy has an influence on Behavioral Intentions

2.10. Relationship between Trust and Behavioral Intention

According to Soedarto, cited by Miraz, trust is a factor that affects people's behavior intentions (Miraz et al., 2022). The relationship between intent and belief is a crucial determinant of a person's behavioral intentions when using technology (Ku-mahamud et al., 2019). As a novel investment option in Indonesia, the level of confidence in crypto assets correlates positively with investment intent (Lim et al., 2022). Based on the preceding explanation, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H3 : Trust has an influence on Behavioral Intention

2.11. Relationship between Government Regulation and Behavioral Intention

According to (Wu et al., 2022), regulations and government support play a significant role in preventing uncertainty in the use of new technologies, specifically crypto assets. According to research (Putra & Darma, 2019), government regulation has a substantial positive impact on the behavioral intent to use Bitcoin. According to (Albayati et al., 2020; Saputra & Darma, 2022), government regulations have an effect on the intention to use cryptocurrencies because clear regulations can avoid uncertainty in transactions, provide security, offer protection, and solve problems encountered by users due to government oversight of crypto transactions. Government threats to ban cryptocurrencies in their countries can also reduce people's desire to use cryptocurrencies in those nations (Gillies et al., 2020). The researcher proposes the following hypothesis based on the preceding explanation:

H4 : Government Regulations have an influence on Behavioral Intentions

2.12. Gender Moderates Subjective Norms on Behavioral Intentions

Multiple studies have utilized gender as a moderating variable between subjective norms and behavioral intentions. In developing the UTAUT theory, Venkatesh explains that the relationship between social influence and behavioral intentions is influenced by gender (Venkatesh et al., 2022). In his research, (Cabanillas et al., 2021) found a correlation between subjective norms and gender-modified intentions in the use of new technology; in this study, crypto could be considered a new technology. In contrast to this assertion, (Novendra & Gunawan, 2017) found that there was no positive relationship between social influence on behavioral intention moderated by gender in Indonesian Bitcoin users. According to (Nurbarani & Soepriyanto, 2022), demographic factors such as gender have no effect on the relationship between subjective norms and the intent to invest in crypto assets. Based on the preceding explanation, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H5 : Gender moderates the relationship between Subjective Norms and Behavioral Intentions

2.13. Gender Moderates Financial Literacy on Behavioral Intentions

According to previous research, there is a correlation between gender, financial literacy, and behavioral intent. Previous research has demonstrated that men are more financially literate than women (Chen, 2021; Falahati & Paim, 2011; Lachance & Legault, 2007). Other studies have demonstrated that women have greater financial literacy than men (Kim et al., 2011; Lusardi & Tufano, 2015). (Asandimitra et al., 2019) discovered that career women have a high level of financial literacy because they are disciplined in developing good financial planning, allowing them to continue investing their extra funds for investment.

Other studies have found that gender has no effect on financial literacy or behavioral intentions. Financial literacy is known to be insignificant in women's investment decisions (Bannier & Neubert, 2016). (Ansar et al., 2019; Fazli & Aw, 2021) demonstrates that men and women have the same behavioral intentions because there is no difference in men and women's financial literacy towards financial behavior, which in this case can be considered investment behavior. (Pertiwi et al., 2020) discovered in his research that gender cannot moderate the relationship between financial knowledge and financial decisions, which can be interpreted as an investment. Gender has no bearing on their investment decision. Based on the above explanation, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H6 : Gender moderates the relationship between Financial Literacy and Behavioral Intention

2.14. Gender Moderates Trust on Behavioral Intentions

Several previous studies discovered a link between beliefs, gender, and behavioral intentions. According to (Astika & Sari, 2019; Senkardes & Akadur, 2021), when viewed from a gender perspective, women are more likely than men to believe in low-risk investments. According to Oliveira et al.,discovered in their research that, based on gender, women prefer investments in the form of art, antiques, or gold and silver, which have lower risk than investments made by men. such as stocks, real estate, or, in this case, investment in crypto assets (Oliveira et al., 2017).

Gender does not moderate the relationship between beliefs and behavioral intentions, according to other studies. (Kayani et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Zamzami, 2021) discovered no difference in men's and women's beliefs about having behavioral intentions in his study. Based on the explanation above, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H7 : Gender moderates the relationship between Trust and Behavioral Intention

2.15. Gender Moderates Government Regulation on Behavioral Intentions

According to (Kayani et al., 2021), the government plays a significant role in influencing men and women to own crypto assets. (Huang, 2019) discovered that government regulations can influence their desire to own crypto assets. Weilun explained that men are more likely to want to own crypto assets if the government can implement regulations to reduce risk in crypto transactions. Weilun's research discovered that what women did had no effect on them. Based on the explanation above, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis:

H8 : Gender moderates the relationship between Government Regulation and Behavioral Intentions

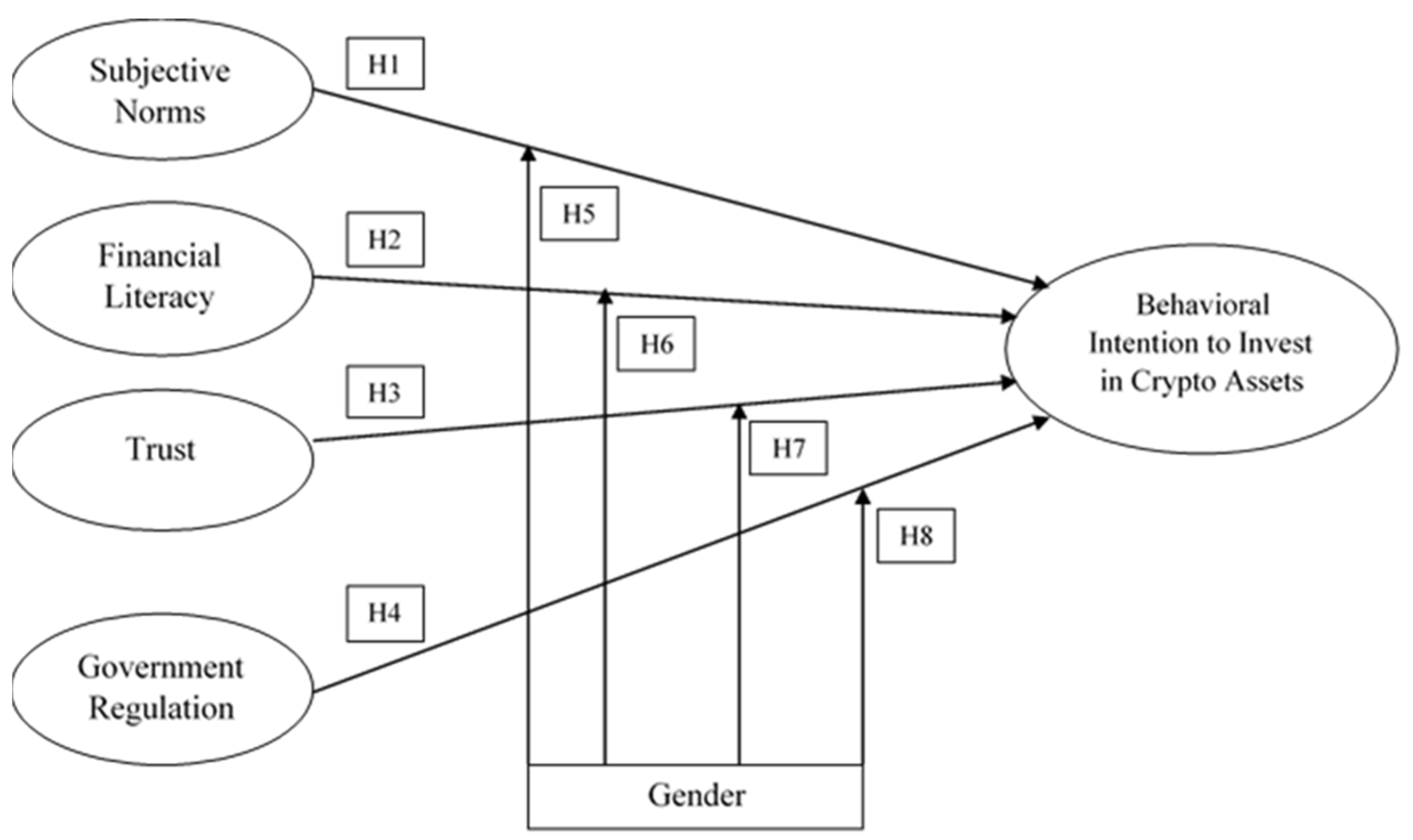

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Methodology

The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique is used in this study to take a quantitative approach. This study employs a purposive sampling strategy with respondents who have invested in investment instruments other than crypto assets. Because they were considered legal to invest, respondents over the age of 17 were sampled. The majority of the sample came from the capital city (Jakarta), followed by the surrounding provinces.

Google Form was used to collect data via Whatsapp and Instagram from 27 October to 7 November 2022. The pilot survey was administered to 34 respondents in September 2022 for validity and reliability testing. The responses obtained from the pilot survey are used to improve the final survey, particularly to replace unclear information with direct, easy-to-understand language so that it is unambiguous and on target. In addition, 196 respondents who responded to the distributed survey questionnaire were obtained, and 149 respondents who had invested were selected.

This study employs a modified Likert scale measurement with four scales, where 1 indicates Strongly Disagree, 2 indicates Disagree, 3 indicates Agree, and 4 indicates Strongly Agree. Referring to (Hair et al., 2010), the minimum sample can be calculated by multiplying the number of indicators by a multiplier factor between 5 and 10. This study employs a multiplier factor of 5 with a total of 16 indicators, resulting in a minimum of 80 respondents. A total of 149 respondents exceeded the required minimum sample size.

Using the SEM-PLS method and the variables of subjective norms from the Theory of Planned Behavior in conjunction with other variables such as financial literacy, trust, and government regulation, as depicted in

Figure 1, the emergence of an intention to invest in crypto assets is investigated. The analysis was conducted in four stages: descriptive analysis to describe the data observed by the researcher, outer model analysis to determine the validity and reliability of the research questionnaire, inner model analysis to examine the influence between variables and hypothesis testing, and multi-group analysis to compare the two groups, namely men and women, and their moderating effect on the relationship between variables.

The question items of construct variables and indicator items are shown in

Table 1.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

Table 2 indicates that the majority of respondents in this study were female (60%). Eighty percent of respondents are between the ages of 23 and 28 and hold a Bachelor's degree (86%). Private employees make up the majority of respondents (65%), and the majority of them are knowledgeable about crypto assets (85%).

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

SmartPLS 3.0 was used to analyze descriptive analysis data in the form of average, median, minimum value, maximum value, and standard deviation. According to

Table 3, the FL1 indicator has the highest average value of 2,705, while the SN2 value has the lowest average value of 1,505. According to the median value, all indicators have median values of 2 or 3, indicating that the majority of respondents selected "Disagree" or "Agree." All indicators have a value of 1, indicating that some respondents selected "strongly disagree" in response to the given questionnaire statement. All indicators have a maximum score of 4, indicating that some respondents selected "strongly agree" in response to questionnaire statements. The SN2 indicator has the lowest standard deviation value at 0.746, while the BI1 indicator has the highest standard deviation value at 1.007.

Each indicator displays the results of various categories, namely "bad" and "good" as seen from the interval scale, based on the average value.

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the interval scale and category rating indicators.

4.3. Outer Model Analysis

In order to test convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability, data were processed using SmartPLS 3.0 for outer model analysis. The outer loading and average variance extracted (AVE) values of each indicator with a value greater than 0.5 indicate convergent validity testing (Hair et al., 2019). In addition, the cross loading value and the results of the Fornell-Larcker criterion measurement determine the discriminant validity. The cross loading value must be greater than 0.70 for the test to be considered valid for discrimination (Hair et al., 2019). On the same variable, the value of the Fornell-Larcker criterion test must be greater than on other variables. Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, which must have a value above 0.70, can be used to determine the reliability of a test (Ghozali & Latan, 2015).

Table 5 demonstrates that the outer loading value exceeds 0.50. The AVE value is also greater than 0.50, indicating that all indicators used in the study have a high degree of correlation with one another. In addition, based on the value of Cronbach's alpha and the composite reliability, the value is above 0.70, indicating that all the employed indicators are valid and reliable.

In addition,

Table 6 reveals that the cross loading of an indicator on the variable is greater than 0.70 when compared to other variables. In addition,

Table 7 demonstrates that in the Fornell-Larcker criterion test, the AVE square root value of the variable is already greater when compared to the other variables. This demonstrates that each variable possesses a high degree of discriminant validity.

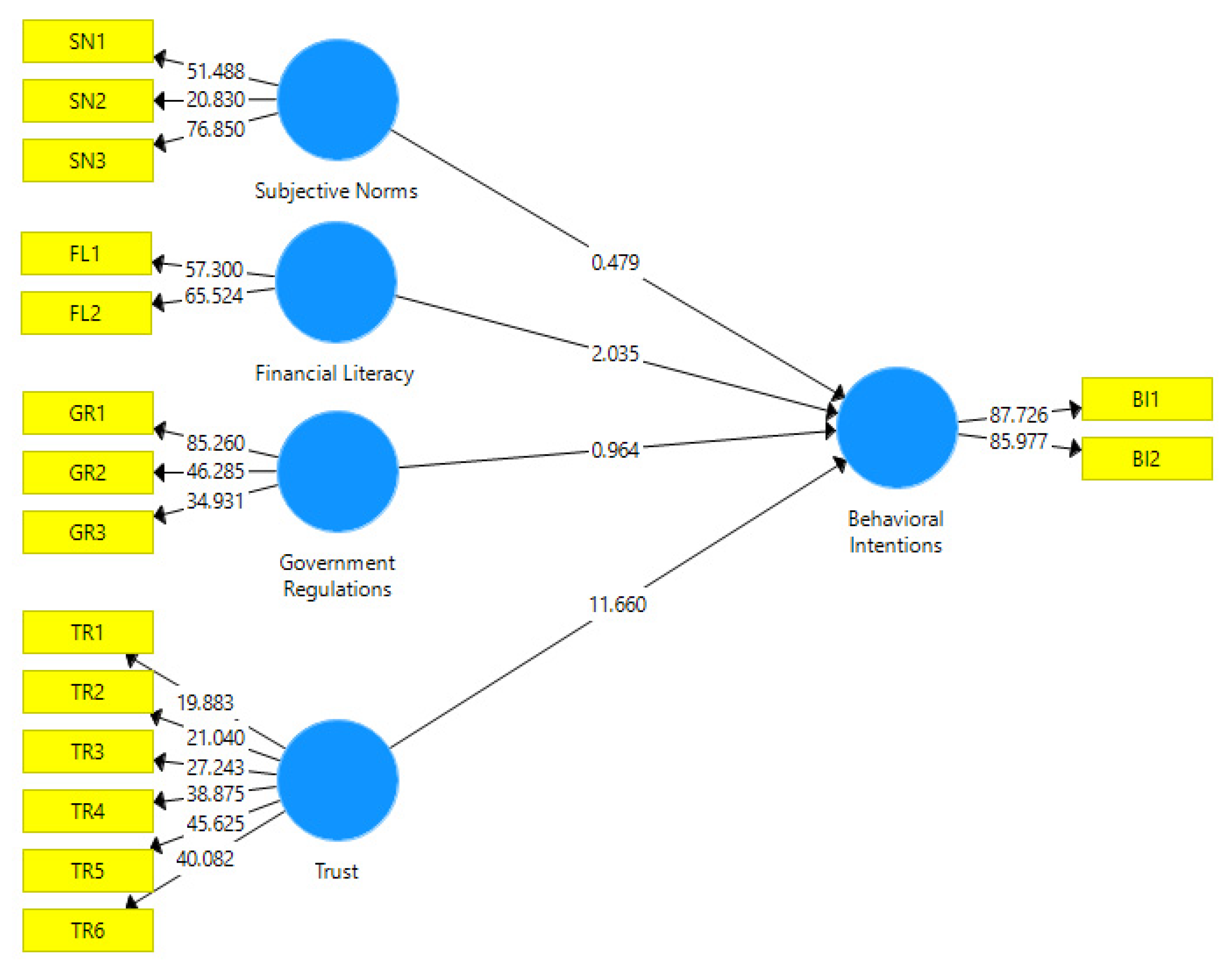

4.4. Inner Model Analysis

In the inner model analysis, testing the coefficient of determination (R

2), the effect size (f

2), and the Path Coefficients can be performed. According to (Ghozali & Latan, 2015), for the purpose of measuring the coefficient of determination, a value of 0.75 is deemed to have a strong influence, a value of 0.50 is deemed to have a moderate effect, and a value of 0.25 is deemed to have a weak influence. According to

Table 8, the classification of the research model's strength is 0.729%. According to these findings, subjective norms, government regulations, financial literacy, and trust can explain 72.9% of behavioral intentions, while the remainder can be explained by other variables. Furthermore, these findings indicate that the influence of exogenous variables, namely subjective norms, government regulations, financial literacy, and trust, has a moderate effect on the endogenous variable, namely behavioral intentions.

In the effect size test, a value of 0.35 is deemed to have a large effect, while a value of 0.15 is deemed to have a moderate effect, and a value of 0.02 is deemed to have a small effect (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 9 reveals that the trust variable (TR) has the greatest impact on behavioral intention (BI) with a f

2 value of 0.973%. The financial literacy variable (FL) has a moderate effect on behavioral intention (BI), with a f

2 of 0.041. Lastly, government regulations (GR) and subjective norms (SN) have the least impact on behavioral intention (BI), with respective f

2 values of 0.008 and 0.002.

Path coefficient testing requires a t-value of 1.96, a 5% significance level, and a p-value less than 0.05 (Hair et al., 2017). A bootstrap procedure can be used to test hypotheses about the effect of exogenous variables on endogenous variables (Hair et al., 2019). The path coefficients test shows that the TR variable has the highest relationship with BI (0.763) and the GR variable the lowest (-0.063). It is also known that the variables GR, SN, FL, and TR to BI have t-values less than 1.96 and more than 1.96, respectively. In the table, GR and SN variables have p-values above 0.05, while FL and TR variables have values below 0.05. Based on the data that has been processed using the bootstrap procedure of 5000, it can be said that the GR and SN variables have no significant relationship with the BI variable. Meanwhile, the variables FL and TR to BI have a significant relationship.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients test results.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients test results.

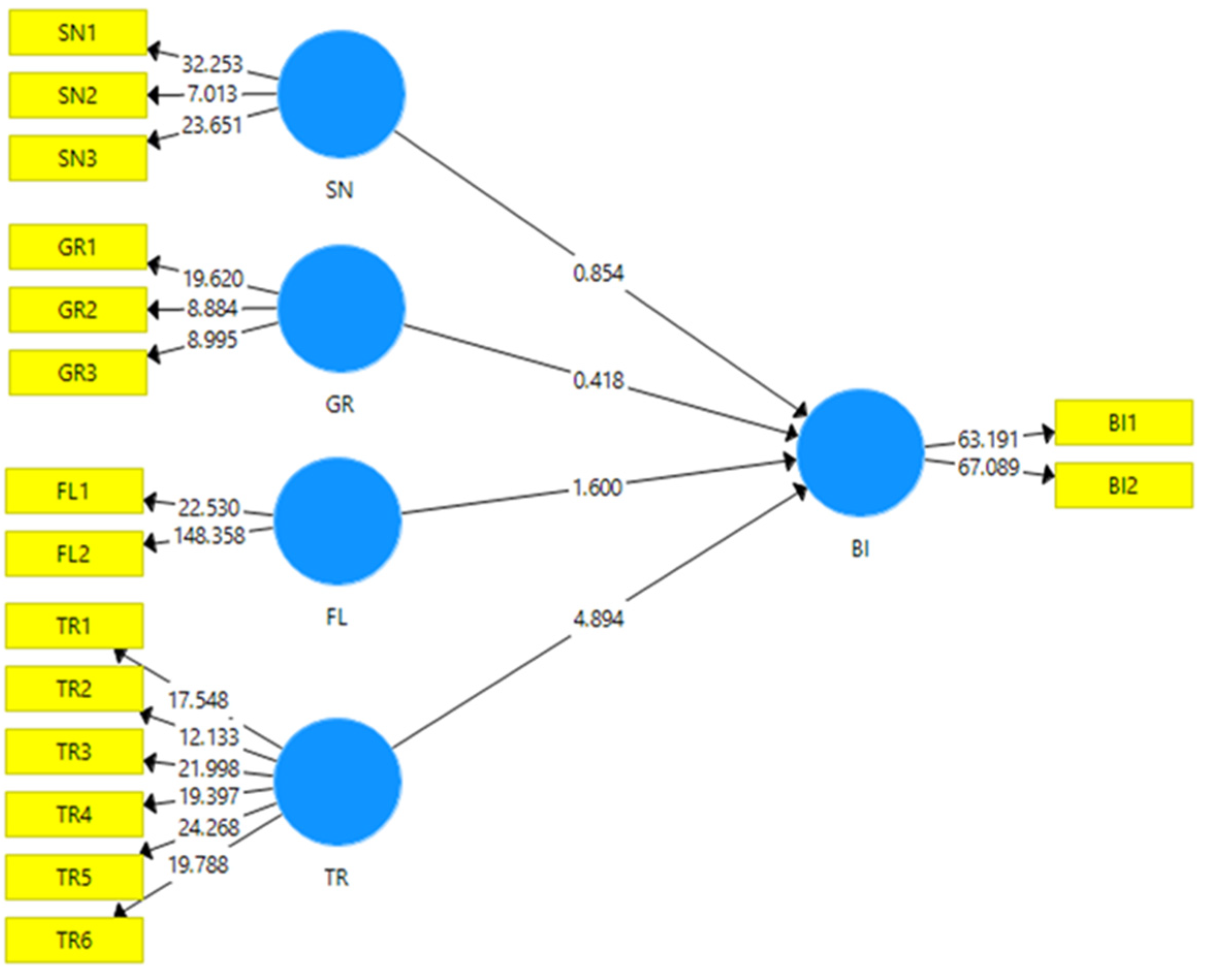

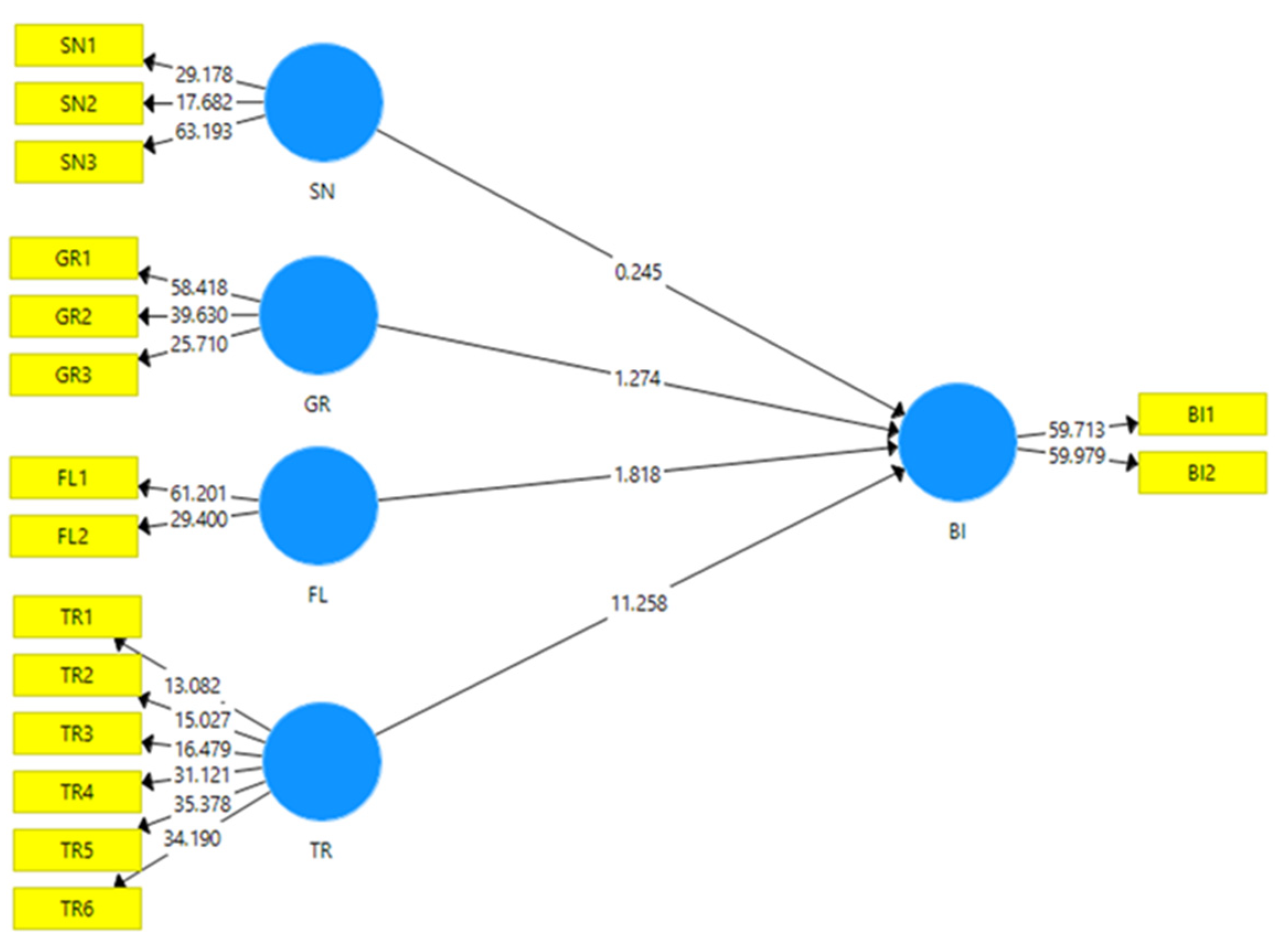

4.5. Multigroup Analysis

A multigroup analysis was performed to see if there were any differences in how exogenous variables affected endogenous men and women. A bootstrapping procedure of 5000 was used in the test to determine the R-Square value as well as the T-statistics value. This procedure is used to determine the effect of the exogenous variables' significance on the endogenous variables.

According to

Table 11, the trust variable with a value of 0.603 has the highest R-square value for the male group. Then, the trust variable receives a T-statistics value greater than 1.96 out of 4,894 samples. In the male group category, only the trust variable has a moderate effect on the behavioral intention to invest in crypto assets. Similarly, in the women's group category, the trust variable had the highest R-Square value (0.863) and was included in the strong category. The T-statistics value indicates that only the trust variable has a significant impact, with a value of 11,258. This indicates that only the trust variable has a significant impact on the women's group's behavioral intention to invest in crypto assets.

Figure 3.

Path coefficients test results for the male group.

Figure 3.

Path coefficients test results for the male group.

Figure 4.

Path coefficients test results for the female group.

Figure 4.

Path coefficients test results for the female group.

After the bootstrapping test is carried out, it is necessary to carry out the randomization or permutation test procedure. The path coefficient of each subsample will be compared and its significance tested with the Smith-Satterthwait test. The test results can be seen in

Table 12.

Based on

Table 12, the T-statistic value is calculated as follows:

Based on these calculations, only the trust variable (TR) has a value greater than 1.96, indicating that the two paths differ significantly between men and women. Gender moderates the relationship between trust and behavioral intention (BI), but not subjective norm (SN), financial literacy (FL), or government regulation (GR).

Consequently, based on the results of the path coefficients analysis and multigroup analysis, the previously formulated hypotheses can be tested.

Table 13 displays the outcomes of the hypothesis testing. After testing the hypotheses, only three of the eight existing hypotheses were accepted, namely financial literacy and the belief that they influence behavioral intentions. The relationship between beliefs and behavioral intentions is also known to be moderated by gender, with greater trust in women's groups than in men's.

5. Discussion

This study aims to determine the factors that influence an individual's decision to invest in crypto assets so that the number of crypto asset owners in Indonesia continues to rise. This study employs the theory of planned behavior because it is suitable for explaining the intention to invest in crypto assets. In addition, researchers added the variables of financial literacy, trust, and government regulations as additional predictors of this behavioral intention. Gender is also used as a moderator to determine if gender differences can differentiate the relationship between subjective norms, financial literacy, trust, and government regulations on the intention to invest in crypto assets. In order to achieve this objective, researchers collected data via Whatsapp and Instagram using a Google form. From this data collection, 196 respondents were collected, and 149 were ultimately chosen based on the criteria specified. The collected data were examined using SEM-PLS.

In line with previous research, the study demonstrates that subjective norms have no effect on behavioral intentions (Arias-oliva et al., 2019; Ayedh et al., 2020; Baur et al., 2015; Echchabi, Omar, et al., 2021; Mazambani & Mutambara, 2019; Nurbarani & Soepriyanto, 2022; Nurhayani et al., 2022; Zamzami, 2020). It is known that the influence and opinions of others have no effect on their intention to invest. (Ayedh et al., 2020) explains that because other people lack experience investing in crypto assets, they are unable to offer advice or opinions that could influence an individual's decision to invest. According to (Mazambani & Mutambara, 2019), subjective norms may have no effect because investment is a private matter, so there is no need for others to intervene. When viewed from a demographic perspective, having investment experience and being dominated by Bachelor's degree holders contributes significantly because they recognize that investments must be made based on an understanding of these assets and not on the influence of others. As the majority of respondents are between the ages of 23 and 28, they are more receptive to new technological innovations, including crypto, than previous generations. Additionally, their proficiency with technology enables them to access all information regarding crypto assets via the internet and social media.

In line with the previous study, the results of this study indicate that financial literacy influences the intention to invest in crypto assets (Atkinson & Messy, 2016; Jariyapan et al., 2022; Zhao & Zhang, 2021). This study demonstrates that the majority of respondents have adequate knowledge of crypto assets and a positive financial outlook, as they are able to manage the risks associated with these investments. Because the respondents selected have invested, they have a high level of financial literacy. The dominance of respondents between the ages of 23 and 28 is also influential because they are more receptive to new information than older respondents. Since the majority of respondents are employed, they also gain knowledge from their coworkers and, if they work in industries related to investment, from their work assignments.

Based on several previous studies, it is also known that there is a correlation between trust and the intention to invest in crypto assets (Alaeddin & Altounjy, 2018; Farhana & Muthaiyah, 2022; Lim et al., 2022; Nuryyev et al., 2018). The greater a person's confidence in cryptocurrencies, the more likely they are to invest in cryptocurrencies. Blockchain technology relies heavily on trust (Shin, 2019), and this study demonstrates that respondents have faith in the crypto blockchain ecosystem to keep their data and transactions safe. In addition, they believe that the public ledger provided by crypto facilitates transparency. This also leads them to have faith in Indonesian exchange companies. Even though it is known that trust has an impact, there is still room for improvement in preventing fraud and ensuring the legality of cryptocurrencies. For instance, the news that Terra Luna and FTX used their investment funds for other purposes without their knowledge and that they filed for bankruptcy successfully reduced their level of confidence in investing in crypto assets. Even though there is already a legal basis from the Indonesian government regarding the acceptability of crypto assets as investments, the government still imposes restrictions on their use.

In contrast to previous findings, it is now known that government regulations have no impact on the intention to invest in crypto assets (Putra & Darma, 2019). This may explain why the number of crypto asset owners in Indonesia continues to rise despite government warnings to the contrary. This could be due to the respondents' high risk tolerance, given that they had previously invested. Then, due to the dominance of the younger generation, it will be easier for them to accept new crypto-related information in order to gain a deeper understanding of investing in this asset. In the meantime, because crypto regulations are still in development, they cannot yet have a significant impact on their intention to invest in this asset. Their interest in investing in crypto assets appeared to circumvent the government's own regulations because they did not expressly prohibit their use, resulting in an increase in the amount of investment.

This study also discovered that gender does not moderate the relationship between subjective norms, financial literacy, and government regulations and behavioral intentions, but does moderate the relationship between beliefs and behavioral intentions. Men and women are not affected by social pressure or environmental influences because investing in other assets improves their financial outlook, allowing them to recognize that investments must be made based on their own needs and not due to external coercion. There was also no difference between men and women in terms of the effect of their financial literacy on the intention to invest in crypto assets. Due to the Internet's accessibility and the evolution of attitudes, both men and women possess the same level of investing knowledge today. Both exchanges and the government have disseminated a wealth of information about crypto assets, enabling potential investors to expand their horizons and consider investing in these assets.

According to (Huang, 2019), if the government enacts regulations that reduce the risk of investment transactions, men will have a greater propensity to desire crypto assets. Nonetheless, this was not discovered in this study. There was no difference between men and women regarding the impact of government regulations on their investment intentions. This could be the result of regulations that are still in the process of being developed. In contrast to the three previously described variables, this study revealed a difference between men's and women's confidence in investing in crypto assets. Men have moderate confidence in investing in this crypto asset, while women have strong confidence, according to research. This result contradicts several previous studies (Astika & Sari, 2019; Kayani et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2017; Senkardes & Akadur, 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Zamzami, 2021). Women today are courageous enough to make risky investments. Due to their investment experience and knowledge, women can now dispel the stereotype that they are only interested in low-risk investments. Their trust increases because the services of the exchange and the cryptocurrency itself are transparent, secure, and able to maintain their privacy (Oliveira et al., 2017; Zamzami, 2021).

6. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to identify the factors that influence an individual's intention to invest in crypto assets. This study investigates the relationship between subjective norms, financial literacy, trust, and government regulations and the intention to invest in crypto assets. From 27 October to 7 November 2022, 149 respondents filled out an online questionnaire to collect research data, which was then analyzed using SmartPLS 3.0 statistical software.

Only financial literacy and trust are shown to have an effect on the intention to invest in crypto assets, out of the four variables selected as exogenous variables. This indicates that the behavioral intention to invest in crypto assets is based on their existing knowledge of crypto assets and how to use them. As a result, they ultimately trust the blockchain system used in crypto transactions and exchanges as the means for buying and selling their assets. This study also found that women's trust influences their intention to invest in crypto assets more strongly than men's.

6.2. Implications

This research has implications for the Indonesian government and international trade. In an effort to increase investor confidence in crypto assets, exchanges are advised to provide proof-of-reserves and proof-of-liquidity as evidence of their transparency and ability to disburse investor funds. In addition, exchanges must be able to establish a reserve fund in lieu of fraudulent user funds from this investment. This represents an exchange's duty to its users.

In order to increase government influence in forming public intentions to invest in crypto assets, the government must enact regulations capable of preventing fraudulent acts in investments, such as requiring exchanges to submit their business plans for one year and requiring exchanges to issue proof-of-reserve. The government also enacted a rule mandating that half of the top exchange company officials be Indonesian nationals who could be held accountable for investment violations. Before investing in exchanges, the government must select a third party as a depository to make it easier to monitor the circulation of funds and prevent fraud or violations. The government can also collaborate with educational institutions to increase crypto asset literacy. In addition, governments and exchanges are encouraged to use social media to disseminate information regarding the benefits and risks associated with investing in crypto assets.

6.3. Limitations and Recommendation

This study aims to explain the origins of the growing desire to invest in crypto assets. This research is limited by the fact that the majority of respondents reside in the nation's capital, where it is easier to access information about crypto asset investments. Since the majority of respondents are urbanites, the results are less variable. Additionally, the level of education in urban areas is higher than in other regions. For further study, it is necessary to conduct crypto asset investment research on individuals who have never invested before. Then, research can also be conducted on students' intentions to invest in crypto assets at schools and universities, as this research may yield different results.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the.corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior : Frequently asked questions. April, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Alaeddin, O., & Altounjy, R. (2018). Trust , Technology Awareness and Satisfaction Effect into the Intention to Use Trust , Technology Awareness and Satisfaction Effect into the Intention to Use Cryptocurrency among Generation Z in Malaysia. November, 7–10. [CrossRef]

- Albayati, H., Kim, K., & Rho, J. J. (2020). Acceptance of financial transactions using blockchain technology and cryptocurrency: A customer perspective approach. Technology in Society, 101320. [CrossRef]

- Almajali, D. A., Ed, R., Deh, M., & Dahalin, Z. M. (2022). Factors influencing the adoption of Cryptocurrency in Jordan : An application of the extended TRA model Factors influencing the adoption of Cryptocurrency in Jordan : An application of the extended TRA model. [CrossRef]

- Alshamy, S. A. (2019). Factors Affecting Investment Decision Making : Moderating Role of Investors Characteristics. 5, 965–974.

- Altowairqi, R. I., Tayachi, T., & Javed, U. (2021). Gender Effect on Financial Risk Tolerance: The Case of Saudi Arabia. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 18(13), 516–524.

- Anggraini, R. W. (2021). Tax compliance kendaraan bermotor ditinjau dari Theory of Planned Behavioral : konseptual model. 3, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Ansar, R., Rahimie, M., Abd, B., Osman, Z., & Fahmi, M. S. (2019). The Impacts of Future Orientation and Financial Literacy on Personal Financial Management Practices among Generation Y in Malaysia : The Moderating Role of The Impacts of Future Orientation and Financial Literacy on Personal Financial Management Practices. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, July 2021. [CrossRef]

- Anser, M. K., Hussain, G., Zaigham, K., Rasheed, M. I., Pitafi, A. H., Iqbal, J., & Luqman, A. (2020a). Social media usage and individuals ’ intentions toward adopting Bitcoin : The role of the theory of planned behavior and perceived risk. August. [CrossRef]

- Anser, M. K., Hussain, G., Zaigham, K., Rasheed, M. I., Pitafi, A. H., Iqbal, J., & Luqman, A. (2020b). Social media usage and individuals ’ intentions toward adopting Bitcoin : The role of the theory of planned behavior and perceived risk. International Journal of Communication Systems, November. [CrossRef]

- Arias-oliva, M., Pelegrín-borondo, J., Matías-clavero, G., & Arias-oliva, M. (2019). Variables Influencing Cryptocurrency Use : A Technology Acceptance Model in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(March), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Arli, D., Esch, P. Van, & Laurence, A. (2020). Do consumers really trust cryptocurrencies ? [CrossRef]

- Asandimitra, N., Aji, T. S., & Kautsar, A. (2019). Financial Behavior of Working Women in Investment Decision-Making. 11(2), 10–20. [CrossRef]

- Astika, M. Q., & Sari, R. C. (2019). THE EFFECT OF FINANCIAL KNOWLEDGE LEVEL , EXPERIENCED REGRET , AND GENDER ON STUDENT INTEREST IN SECURITIES INVESTMENT ( Study at Faculty of Economics Student Yogyakarta State University ). 1–13.

- Atkinson, A., & Messy, F.-A. (2016). Measuring Financial Literacy : Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education ( INFE ) Pilot Study. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development Working Paper on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions 15, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ayedh, A. M., Echchabi, A., Battour, M., & Omar, M. M. S. (2020). Malaysian Muslim investors ’ behaviour towards the blockchain-based Bitcoin cryptocurrency market. Journal of Islamic Marketing, February. [CrossRef]

- Bannier, C. E., & Neubert, M. (2016). Gender differences in financial risk taking : The role of financial literacy and risk tolerance. Economics Letters, 145, 130–135. [CrossRef]

- Baur, A. W., Julian, B., Bick, M., & Bonorden, C. S. (2015). Cryptocurrencies as a Disruption ? Empirical Findings on User Adoption and Future Potential of Bitcoin and Co. International Federation for Information Processing, 63–80. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R., Czepluch, J. S., Lollike, N., & Malone, S. (2016). BLOCKCHAIN – THE GATEWAY TO TRUST-FREE CRYPTOGRAPHIC BLOCKCHAIN – THE GATEWAY TO TRUST-FREE CRYPTOGRAPHIC TRANSACTIONS. June.

- Bhuvana, R., & Aithal, S. (2022). Investors Behavioural Intention of Cryptocurrency Adoption – A Review based Research Agenda. International Journal of Applied Engineering and Management, March, 125–148. [CrossRef]

- Broome, T. (2011). Using the theory of planned behaviour and risk propensity to measure investment intentions among future investors Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Risk Propensity to Measure ... January.

- Bunjaku, F., Gjorgieva-trajkovska, O., & Miteva-Kacarski, E. (2017). CRYPTOCURRENCIES – ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES. 31–39.

- Cabanillas, F. L., Singh, N., Kalinic, E., & Trujillo, E. C. (2021). Examining the determinants of continuance intention to use and the moderating effect of the gender and age of users of NFC mobile payments : a multi - analytical approach. Information Technology and Management. [CrossRef]

- Chainalysis. (2022). Crypto Adoption Steadies in South Asia, Soars in the Southeast. Chainalysis. https://blog.chainalysis.com/reports/central-southern-asia-oceania-cryptocurrency-geography-report-2022-preview/.

- Chen, H. (2021). Gender Differences in Personal Financial Literacy Among College Students. January 2002.

- Cristofaro, M., Economia, F., Tor, R., & Giardino, P. L. (2022). Behavior or culture ? Investigating the use of cryptocurrencies for electronic commerce across the USA and China. [CrossRef]

- Echchabi, A., Aziz, H. A., & Tanas, I. N. (2021). Determinants of investment in cryptocurrencies : The case of Morocco. RAFGO, 1(1), 1–6. https://akuntansi.pnp.ac.id/rafgo/index.php/RAFGO/article/view/2.

- Echchabi, A., Omar, M. M. S., & Ayedh, A. M. (2021). Factors influencing Bitcoin investment intention : the case of Oman. Int. J. Internet Techology and Secured Transactions, 11(1), 1–15. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342324886_Factors_Influencing_Bitcoin_Investment_Intention_The_case_of_Oman.

- Falahati, L., & Paim, L. (2011). Gender Differences In Financial Well-Being Among College Students. 5(9), 1765–1776.

- Farhana, K., & Muthaiyah, S. (2022). Behavioral Intention to Use Cryptocurrency as an Electronic Payment in Malaysia. Journal of System and Management Sciences, 12(4), 219–231. [CrossRef]

- Fazli, M., & Aw, E. C. (2021). Financial Literacy , Behavior and Vulnerability Among Malaysian Households : Does Gender Matter ? 15(February), 241–256.

- Franco, P. (2015). Understanding Bitcoin Cryptography , engineering , and economics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Gazali, H. M., Muhamad, C., Bin, H., Ismail, C., & Amboala, T. (2019). Bitcoin Investment Behaviour : A Pilot Study. International Journal on Perceptive and Cognitive Computing, 5(2), 81–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.31436/ijpcc.v5i2.97.

- Ghozali, I., & Latan, H. (2015). Partial Least Squares: Konsep, Teknik, dan Aplikasi Menggunakan Program SmartPLS 3.0 untuk Penelitian empiris (2nd ed.). Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

- Gillies, F. I., Lye, C., & Tay, L. (2020). Determinants of Behavioral Intention to use Bitcoin in Malaysia. Journal of Information System and Technology Management, 5(19), 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis.pdf (7th ed.).

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis. Cengage.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (K. DeRosa (ed.); 2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Hasani, M. N. (2022). Analisis Cryptocurrency sebagai Alat Alternatif dalam Berinvestasi di Indonesia pada Mata Uang Digital Bitcoin. Jurnal Ilmiah Ekonomi Bisnis, 8(Juli), 329–344.

- Heidarian, E. (2019). The impact of trust propensity on consumers ’ cause-related marketing purchase intentions and the moderating role of culture and gender. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 0(0), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. (2019). The impact on people ’ s holding intention of bitcoin by their perceived risk and value. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 3570–3585. [CrossRef]

- Huda, N., & Hambali, R. (2020). Risiko dan Tingkat Keuntungan Investasi Cryptocurrency. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Bisnis: Performa, 17(1), 72–84.

- Huong, N. T. L., Oanh, N. T. L., & Linh, H. N. N. (2021). Testing Impact of Personal Innovativeness on Intention to Invest in Cryptocurrency Products of Vietnamese People: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). International Conference on Emerging Challenges: Business Transformation and Circular Economy, November, 147–157. [CrossRef]

- Hutasuhut, S., & Article, H. (2018). The Roles of Entrepreneurship Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, Family, Education, and Gender on Entrepreneurial Intention. 13(1), 90–105. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Lee, J., & Kim, H. (2019). Perceived innovativeness of drone food delivery services and its impacts on attitude and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of gender and age. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81(December 2018), 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Irma, D., Maemunah, S., Zuhri, S., & Juhandi, N. (2021). The future of cryptocurrency legality in Indonesia. Journal of Economics and Business Letters, 1(1), 20–23. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. A., Saidin, Z. H., Ayub, M. A., & Islam, M. S. (2022). Modelling behavioural intention to buy apartments in Bangladesh : An extended theory of planned behaviour ( TPB ). Heliyon, 8(August). [CrossRef]

- Jalan, A., Matkovskyy, R., Urquhart, A., & Yarovaya, L. (2022). The Role of Interpersonal Trust in Cryptocurrency Adoption. [CrossRef]

- Jariyapan, P., Mattayaphutron, S., Gillani, S. N., & Shafique, O. (2022). Factors Influencing the Behavioural Intention to Use Cryptocurrency in Emerging Economies During the COVID-19 Pandemic : Based on Technology Acceptance Model 3 , Perceived Risk , and Financial Literacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(February). [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K., & Rampersad, G. (2018). Journal of Engineering and Trust in driverless cars : Investigating key factors in fl uencing the adoption of driverless cars. April. [CrossRef]

- Kayani, Z. K., Mehmood, R., Haq, A., & Kayani, J. A. (2021). AWARENESS AND ADOPTION OF BLOCKCHAIN : CUSTOMER ’ S INTENTION TO USE BITCOIN IN PAKISTAN. 18(8), 1–23.

- Khan, F., Ahmed, W., & Najmi, A. (2019). Resources , Conservation & Recycling Understanding consumers ’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste : Perspective of a developing country. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 142(September 2018), 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Lataillade, J., & Kim, H. (2011). Family Processes and Adolescents ’ Financial Behaviors. 668–679. [CrossRef]

- Koroma, J., Rongting, Z., Muhideen, S., Yinka, T., Simeon, T., James, S., & Abdulai, I. (2022). Technology in Society Assessing citizens ’ behavior towards blockchain cryptocurrency adoption in the Mano River Union States : Mediation , moderation role of trust and ethical issues. Technology in Society, 68, 101885. [CrossRef]

- Ku-mahamud, K. R., Omar, M., Azzah, N., Bakar, A., & Muraina, I. D. (2019). Awareness , Trust , and Adoption of Blockchain Technology and Cryptocurrency among Blockchain Communities in Malaysia. International Journal on Advanced Science Engineering Information Technology, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Lachance, M. J., & Legault, F. (2007). College Students’ Consumer Competence: Identiying the Socialization Sources. Journal of Research for Consumers, 13(Ward 1974).

- Laopodis, N. T. (2020). Understanding Investments : Theories and Strategies (Issue June). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Lemaster, P., & Strough, J. (2013). Beyond Mars and Venus : Understanding gender differences in financial risk tolerance. JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC PSYCHOLOGY. [CrossRef]

- Lim, F., Lim, D., Othman, J., & Tarmizi, R. M. (2022). The Factors Influencing Cryptocurrency Awareness Among Generation Z in Malaysia : The Roles of Trust , Confidence , and Social Acceptance. Asian Journal of Research in Business and Management, 4(3), 246–257. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/ajrbm/article/view/19089.

- Luis, J., Robledo, R., & Arán, M. V. (2015). The moderating role of gender on entrepreneurial intentions : A TPB Perspective. 11(1), 92–117. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Tufano, L. (2015). Debt literacy , fi nancial experiences , and overindebtedness * (Vol. 14, Issue 4). [CrossRef]

- Mardhiyah, A. (2017). Peranan Analisis Return dan Risiko dalam Investasi. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis, 2(April), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Marinković, V., Đorđević, A., & Kalinić, Z. (2019). Technology Analysis & Strategic Management The moderating effects of gender on customer satisfaction and continuance intention in mobile commerce : a UTAUT-based perspective. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 0(0), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S., & Swail, J. (2014). Gender, risk and finance: Why can’t a woman be more like a man? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, October. [CrossRef]

- Mazambani, L., & Mutambara, E. (2019). Predicting FinTech innovation adoption in South Africa : the case of cryptocurrency. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-tello, J. C., Mora, H., Pujol-Lopez, F. A., & Lytras, M. D. (2018). Social Commerce as a Driver to Enhance Trust and Intention to Use Cryptocurrencies for Electronic Payments. IEEE Access, 6. [CrossRef]

- Miraz, M. H. (2020). Trust Impact on Blockchain & Bitcoin Monetary Transaction. March. [CrossRef]

- Miraz, M. H., Hasan, M. T., Rekabder, M. S., & Akhter, R. (2022). Trust, Transaction Transparency Volatility, Facilitating Condition, Performance Expectancy towards Cryptocurrency Adoption thrugh Intention to Use. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(November), 1–20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356282702_Trust-transaction-transparency-volatility-facilitating-condition-performance-expectancy-towards-cryptocurrency-adoption-through-intention-to-use.

- Mosquera, A., Olarte-pascual, C., & Ayensa, E. J. (2018). The role of technology in an omnichannel physical store: Assessing the moderating effect of gender. 22(1), 63–82. [CrossRef]

- Mushi, H. M. (2020). Intention , Government Regulation , Self-Regulatory Efficacy , Subjective Norm , Idolatry and Consumer Behaviour in Purchasing Pirated Compact Disks ( CDs ) in Mainland Tanzania. 2117, 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Norisnita, M., & Indrianti, F. (2022). Application of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in Cryptocurrency Investment Prediction: A Literature Review. Economics and Business Quarterly Reviews, 5(2), 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Novendra, R., & Gunawan, F. E. (2017). Analysis Of Technology Acceptance And Customer Trust In Bitcoin In Indonesia Using UTAUT Framework. January.

- Nurbarani, B. S., & Soepriyanto, G. (2022). Determinants of Investment Decision in Cryptocurrency : Evidence from Indonesian Investors. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance, 10(1), 254–266. [CrossRef]

- Nurhayani, U., Sitompul, H. P., Herliani, R., & Sagala, G. H. (2022). Intention to Investment Among Economics and Business Students Based on Theory of Planned Behavior Framework. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 204(ICoSIEBE 2021), 159–165. [CrossRef]

- Nuryyev, G., Spyridou, A., Yeh, S., & Achyldurdyyeva, J. (2018). Factors influencing the intention to use cryptocurrency payments : An examination of blockchain economy. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, 303–310. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/99159/.

- Oliveira, T., Alhinho, M., & Rita, P. (2017). Modelling and testing consumer trust dimensions in e-commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 71. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Park, H. W. (2019). Diffusion of cryptocurrencies : web traffic and social network attributes as indicators of cryptocurrency performance. Quality & Quantity, 0123456789. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. W. (2020). Cryptocurrency : The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Cryptocurrency : The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues. Congressional Research Service.

- Pertiwi, T. K., Ika, N., Wardani, K., & Septentia, I. (2020). KNOWLEDGE , EXPERIENCE , FINANCIAL SATISFACTION , AND INVESTMENT DECISIONS : GENDER AS A MODERATING VARIABLE. 22(1), 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q. T., Phan, H. H., Cristofaro, M., & Misra, S. (2021). Examining the Intention to Invest in Cryptocurrencies : An Extended Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior on Italian Independent Investors. International Journal of Applied Behavioral Economics, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q. T., Phan, H. H., Cristofaro, M., Misra, S., & Giardino, P. L. (2021). Examining the Intention to Invest in Cryptocurrencies : An Extended Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior on Italian Independent Investors. International Journal of Applied Behavioral Economics, 10(3), 59–79. [CrossRef]

- Pratomo, G. Y. (2022). Pertumbuhan Cepat Kripto Memiliki Risiko Stabilitas Keuangan. Liputan 6. https://www.liputan6.com/crypto/read/4896316/pertumbuhan-cepat-kripto-memiliki-risiko-stabilitas-keuangan.

- Putra, I. G. N. A. P., & Darma, G. S. (2019). Is Bitcoin Accepted in Indonesia ? International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 4(2), 424–430.

- Rahayu, R., Ali, S., Aulia, A., & Hidayah, R. (2022). The Current Digital Financial Literacy and Financial Behavior in Indonesian Millennial Generation. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 23(1), 78–94. [CrossRef]

- Rasool, N., & Ullah, S. (2020). Financial literacy and behavioural biases of individual investors: empirical evidence of Pakistan stock exchange. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 25(50), 261–278. [CrossRef]

- Rekabder, M. S., Miraz, M. H., Hasan, M. T., & Akhter, R. (2021). Trust, Transaction Transparency Volatility, Facilitating Condition, Performance Expectancy towards Cryptocurrency Adoption thrugh Intention to Use. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(November), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Rice, M. (2019). Cryptocurrency: What is it? In Honors Program of Liberty University. Liberty University.

- Salisa, N. R. (2020). Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Minat Investasi Di Pasar Modal : Pendekatan Theory Of Planned Behaviour ( TPB ). Jurnal Akuntansi Indonesia, 9(2), 182–194. [CrossRef]

- Samsuri, A., Ismiyanti, F., & Narsa, I. M. (2019). Effects of Risk Tolerance and Financial Literacy to Investment Intentions. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 10(9), 40–54. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol10iss9/10904_Samsuri_2019_E_R.pdf.

- Saputra, U. W. E., & Darma, G. S. (2022). The Intention to Use Blockchain in Indonesia Using Extended Approach Technology Acceptance Model ( TAM ). CommIT Journal, 16(1), 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Senkardes, C. G., & Akadur, O. (2021). A RESEARCH ON THE FACTORS AFFECTING CRYPTOCURRENCY INVESTMENTS WITHIN THE GENDER CONTEXT. 10, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. D. . (2019). Telematics and Informatics Blockchain : The emerging technology of digital trust. Telematics and Informatics, 45(September). [CrossRef]

- Syarkani, Y., & Tristanto, T. A. (2022). Examining the predictors of crypto investor decision : The relationship between overconfidence , financial literacy , and attitude. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 11(6), 324–333. https://www.ssbfnet.com/ojs/index.php/ijrbs/article/view/1940. [CrossRef]

- Tandio, T., & Widanaputra, A. A. G. P. (2016). Pengaruh Pelatihan Pasar Modal, Return, Persepsi Resiko, Gender dan Kemajuan Teknologi pada Minat Investasi Mahasiswa. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 16(September), 2316–2341.

- Tang, K. L., Aik, N. C., & Choong, W. L. (2021). A MODIFIED UTAUT IN THE CONTEXT OF M-PAYMENT USAGE INTENTION IN MALAYSIA. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 5(1), 40–59. [CrossRef]

- Trinugraheni, N. F. (2022). Indeks Adopsi Kripto Global 2022 Dirilis, Indonesia di Urutan Berapa? Artikel ini telah tayang di Tribunnews.com dengan judul Indeks Adopsi Kripto Global 2022 Dirilis, Indonesia di Urutan Berapa?, https://www.tribunnews.com/new-economy/2022/09/17/indeks-a. Tribun News. https://www.tribunnews.com/new-economy/2022/09/17/indeks-adopsi-kripto-global-2022-dirilis-indonesia-di-urutan-berapa.

- TripleA. (2022). Cryptocurrency across the world. Triple A.

- Tseng, T. H., Wang, Y., Lin, H., Lin, S., Wang, Y., & Tsai, T. (2022). Relationships between locus of control , theory of planned behavior , and cyber entrepreneurial intention : The moderating role of cyber entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3). [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2022). User Acceptance of Information Technology : Toward a Unified View User Acceptance of Information Technology : Toward a Unified View Published by : Management Information Systems Research Center , University of Minnesota Stable URL : https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036540. February. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, A., Saudi, M. H., & Sinaga, O. (2021). Cryptocurrency - Illusion vs Solution. 12(8), 589–595.

- Wijaya, F. N. A. (2019). BITCOIN SEBAGAI DIGITAL ASET PADA TRANSAKSI ELEKTRONIK DI INDONESIA (Studi Pada PT. Indodax Nasional Indonesia) Firda Nur Amalina Wijaya 1. Jurnal Hukum Bisnis Bonum Commune, 2, 126–136.

- Wu, R., Ishfaq, K., Hussain, S., Asmi, F., Siddiquei, A. N., & Anwar, M. A. (2022). Investigating e-Retailers ’ Intentions to Adopt Cryptocurrency Considering the Mediation of Technostress and Technology Involvement. Sustainability (Switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2017). Determinants of Consumers ’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation : Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecological Economics, 134, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M., Al-Mamun, A., Mohiuddin, M., Nawi, N. C., & Zainol, R. (2021). Cashless Transactions : A Study on Intention and Adoption of e-Wallets. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(831), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zamzami, A. H. (2020). The Intention to Adopting Cryptocurrency of Jakarta Community. Dinasti International Journal of Management Science, 2(2), 232–244. [CrossRef]

- Zamzami, A. H. (2021). Investors’ Trust and Risk Perception Using the Investment Platform: A Gender Perspective. Dinasti International Journal of Management Science, 2(5), 828–841. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q., Sher, A., & Li, Q. (2022). The Impact of Health Risk Perception on Blockchain Traceable Fresh Fruits Purchase Intention in China.

- Zhang, K. (2018). Theory of Planned Behavior : Origins , Development and Future Direction. Internation Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 7(05), 76–83.

- Zhao, H., & Zhang, L. (2021). Financial literacy or investment experience : which is more influential in cryptocurrency investment ? investment. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).