1. Introduction

Social networks can help develop public awareness of disasters and share information in real-time (Epstein, Pawa, & Simon, 2015). Data from social media can help emergency and rescue services in assessing and mitigating natural and technical-technological disasters. They are used for impact and damage assessment, situational awareness and crisis mapping, allowing the dynamics of disasters to be monitored (Avvenuti et al., 2016). The most popular social networks are Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and WeChat. Facebook enables the exchange of multimedia content, photos and videos with other users. Users make so-called virtual friendships and thus can follow the profiles of their "friends". The basic applications that animate users are photos, videos, groups, events, items, notes, and gifts. Users can also create and share their content (Sarac et al., 2015, p. 30).

Social media can be used to communicate in disasters by the public, the services of protection and rescue systems, and educational institutions (Simon, Golberg, & Adini, 2015). According to Rasmussen and Ihlen (2017), social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, are effective channels of communication in crises. Wukich (2015) concluded that social media can be an effective tool in communicating with the public in disasters, but that they require time, and human and material resources, which are often limited. The research was conducted through content analysis of more than 200 newspaper articles, reports and other documents. The results showed that three strategies, namely information dissemination, real-time data monitoring and communication with social network users, are the most effective in reporting disasters to the public (Wukich, 2015).

Since its inception, social media has stood out as a completely new form of communication where information did not go in one direction but moved through a network of connected users. Also, Xiao et al. (2015) note that social media users can both receive and post messages, which has the effect of no longer having to wait for professional journalists to arrive on the scene to report the situation. By using social media, individuals can gather first-hand information and disseminate it in real-time. Social media can greatly contribute to informing the public, as a form of disaster risk management. Chan (2013) explains that four main functions of social media for disaster management can be observed, which include not only the sharing of information, but also the preparation and management of the situation itself, which includes information dissemination, disaster planning and training, and collaborative resolution. problems and decision-making for gathering information. Social media is very important for disaster management because of the growing number of users. Namely, more than half of the world's population uses social media. Today, 4.57 billion people worldwide use the Internet. In addition, there were 5.15 billion unique mobile users in 2020 and only 8% of all Internet users do not use social networks (Kemp, 2020).

During disasters, emergency services must have a comprehensive overview of the situation to coordinate efforts and make informed decisions (Imran et al., 2015; Domingo et al., 2022; Odero & Mahiri, 2022; Kabir et al. 2022; Jha et al., 2021). During disasters, social media is increasingly used to share information. At the same time, emergency response services in disasters face the problem of information overload (Plotnick & Hiltz, 2018). For example, Avvenuti et al. (2016) conducted a case study investigating the early detection of earthquakes and tornado movements based on data shared by users on social networks. Research results show that social media can be significant for assessing the intensity of disasters (Avvenuti et al., 2016). Also, the way social media is used by both individuals and institutions shapes disaster awareness and preparedness (Mano, Kirshcenbaum, & Rapaport, 2019).

Disasters are characterized by a high degree of insecurity and uncertainty, as well as threat perception. In an uncertain situation, citizens affected by a disaster need to seek useful information that can help restore a sense of normalcy. Also, citizens feel the need to know what happened, what the current situation is and whether help is ready and on the way. People often lack information to determine the degree of danger and make appropriate decisions and protective measures. Therefore, it is important to use social networks to share information about disasters (Jurgens & Helsloot, 2017).

Thus, a large amount of information is shared on social networks, including disaster warnings, requests for help, expressions of feelings, and information in the domain of disaster recovery (Jurgens & Helsloot, 2017). In the disaster management process, social media can be used for supervision, monitoring, and information about the situation and the early warning system. Social media can be used as a tool for sharing information and instructions, as well as for real-time alerts. Providing information and guidance on social networks such as blogs can be used to provide advice, by posting information such as emergency phone numbers, locations of hospitals that need blood donations, evacuation routes, etc. They can be used to mobilize volunteers during and after a crisis. In addition, they can improve disaster response by mobilizing volunteers far from the epicentre of the crisis to relay information provided by emergency services. They can also be used to identify survivors and victims. Social media can help citizens find out if their family and friends are safe, while combined with the use of mobile phones help report accidents and send requests for help. Using social media to communicate during disasters can help counter inaccurate press reporting or balance rumours and manage reputational effects. Social media can be used to raise funds and support, by encouraging donations when major disasters occur, or by facilitating the provision of support. During disasters, people/victims who need help often do not know whom to turn to (Cvetković et al., 2019; Cvetković, Nikolić, Nenadić, Ocal, & Zečević, 2020; Cvetković, Roder, Öcal, Tarolli, & Dragićević, 2018; Cvetkovic, Ocal & Ivanov, 2019).

Social media is a valuable source of information about citizens, their habits, attitudes and opinions. Social media users are members of different social groups. Therefore, social networks can serve as a source of information about cultural differences and behavioral patterns of people in communities. This information is important for adapting messages, to ensure that they reach citizens and are interpreted correctly (Adem, 2019; Aleksandrina, Budiarti, Yu, Pasha, & Shaw, 2019; Carla, 2019; Cvetković, 2019). Also, this information is important for developing restoration plans that are tailored to the needs of different social groups (Kapoor et al., 2018). Research results based on the analysis of data contained in tweets and geolocation data show that it is necessary to develop mechanisms of selection and analysis of the huge amount of data available on social networks (Nazer et al., 2019).

1.1. Literary review

Social media allows emergency services to receive valuable information such as eyewitness reports, images or videos. However, the vast amount of data generated during large-scale disasters can lead to information overload. Research conducted by Kaufhold, Bayer and Reuter (2018) indicates that machine learning techniques are suitable for identifying relevant messages and filtering irrelevant messages, thereby mitigating the problem of information overload. Castillo (2016) pointed out the possibilities of using social networks in formal communications and in collecting data shared by social network users. Through qualitative research, Martinez-Rojas et al. (2018) included papers containing selected terms, such as Twitter, emergency, disaster management, etc., and pointed out the importance of information shared by Twitter users for effective disaster response. Saramadu (2020) used the example of Sri Lanka's e-government to show that governments can improve disaster response by using digital technology.

The results of experimental research based on two sets of data, on earthquakes and the behavior of users on Twitter, show that social media provide valuable information that contributes to a more accurate assessment of earthquake intensity (Mendoza, Poblete, & Valderrama, 2019). Based on the analysis of data collected from social networks, Boulton, Shotton and Williams (2016) determined that there is a positive correlation between the occurrence of forest fires and the activity of social network users. Certain social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook and individual blogs, which are most often used to share information (especially in the first 12 hours of an emergency), register the most content generated by citizens themselves (Austin & Jin, 2016). Social media also do not adhere to the more limited schedules of traditional media and allow the general public to access information at any time and from any place. Therefore, they stimulate certain responses in the behaviour of individuals based on that information (Austin & Jin, 2016). Xu et al. (2020) interviewed members of 327 households in communities affected by the July 2019 earthquakes. The results of their research unequivocally show that residents of rural areas rely on disaster information on social media, but that greater presence of information on social media negatively affects disaster risk perception (Xu et al., 2020).

Citizens who use media channels such as newspapers and magazines are more engaged in finding and processing disaster news and information than social media users who receive instant information and opinions (Austin & Jin, 2016). Communication on social media makes access to information more efficient and faster, but increases the risk of exposing the public to unverified or inaccurate information (Austin & Jin, 2016). An analysis of Twitter posts during hurricanes Irene, Jonas, and Sandy indicates that more intense disasters increase the number of climate change-related posts on Twitter (Roxburgh et al., 2019). However, not all information shared by users is relevant. The results show that less than 3% of tweets are relevant for the detection of extreme weather events (Spruce, Arthur, & Williams, 2019). Based on a quantitative study of data collected from Twitter during disasters from 2012 to 2020, Kruspe, Kersten and Klan (2020) concluded that using advanced technologies such as machine learning can improve the monitoring of information shared on social media. networks. Also, new technologies can help in the selection and analysis of information shared on social networks.

Houston et al. (2015) describe various uses of social media in disasters, which include sending and receiving requests for help, helping to gather and document information about what happened in the disaster, providing and receiving disaster response information, and providing and receiving mental health support, that is, behaviour in the event of a disaster. It is also important to note the difference between the type of information that is exchanged. They can be in the form of warnings about disasters, but also the form of requests for help, expressions of emotions and information about disaster recovery (Houston et al., 2015). On the other hand, Gao et al. (2015) divide the generation of situational information into active and passive. Active generation means actively reporting disaster-related cases or seeking help from the authorities. Passive information generation refers to the collection of disaster data from social media to establish awareness of a situation specifically requiring a response from humanitarian organizations. To effectively use social media to disseminate disaster information, emergency responders must have the knowledge and resources necessary to use social media (Stephenson et al., 2018). An analysis of the messages of 56 social media accounts of different organizations involved in the flood protection system yielded insights into the insufficient use of social media in the dissemination of flood information by public services (Stephenson et al., 2018).

During disasters, social media is also used to raise funds. As major disasters exceed the response capabilities of local and national governments, NGOs use social media to initiate, raise, and allocate funding much faster than standard funding channels (Okada, Ishida, & Yamauchi, 2017). Nazer et al. (2019) note that after disasters, social media can be used to share "lessons learned" and as a resource for researchers. They can also be used to improve recovery management, by sending information about rebuilding and recovery, and by helping citizens manage stress. Effective use of social media could improve transparency and trust in public authorities. Social media can be used to inform about the reconstruction and restoration of infrastructure, as well as to identify areas most in need of recovery. They help to identify who and where help is needed, as well as to provide psychological assistance to disaster victims.

Disasters are a source of stress for individuals, and they often need emotional support to regain balance. Therefore, social networks can also be effective in mitigating the psychosocial consequences of disasters (Li et al., 2018). Social media users seek information, and emotional support, and satisfy their need to belong to a community (Li et al., 2018). Healthcare providers, for example, use social media to provide support to members of affected communities after disasters (Grover, Kar, & Davies, 2018). A review of the literature related to the use of social media in disasters indicates the existence of an impact on reducing uncertainty, through the provision of disaster information and the encouragement of cooperation and community (Jurgens & Helsloot, 2017).

Social media users are sharing information about the damage in affected communities. This is important for directing efforts and allocating resources in the best possible way, and to ensure the establishment of the normal functioning of communities as quickly as possible. Glasgow et al. (2016), for example, investigated positive tweets expressing citizens' gratitude for assistance, which has a positive impact on citizens' trust in local authorities. Grace (2020) conducted a qualitative analysis of 6 sets of a total of 22,706 Twitter posts, collected based on geolocation and keywords. His research results show that Twitter posts are useful for tracking storm damage, and infrastructure damage, and creating early warnings.

Social media has a significant impact on public opinion and key topics on social media during the pandemic were health risks, quarantine, and the credibility of information sources (Yu et al., 2020). The coronavirus pandemic has intensified concerns about the role of social media in spreading misinformation (Brennen, 2020). Although people are less likely to trust the news they find on social media, they are finding it increasingly difficult to recognize misinformation, and more and more of them are being exposed to misinformation. For example, there has been an increase in the number of profiles on social networks that spread information about drugs for the virus that may pose a risk to human health, as well as the number of pages that undermine public trust in experts and governments (Brennen, 2020). On the other hand, a large amount of misinformation motivates people to find sources that are credible and avoid social networks (Brennen, 2020).

The search for information on social networks culminated during the pandemic, and especially during the duration of measures to prevent the spread of the virus. Research has shown that as many as 40% of US residents believe that the news has worsened the uncertainty and feeling of helplessness, and 70% point out that they need a break from the news about the coronavirus (Pew Research Center, 2020). Too much information increases anxiety in many people and can cause depression Pew Research (Savage, 2020). At the same time, people have trouble separating important information from irrelevant information; for example, along with news about the number of infected and the death rate, measures to prevent the spread of the virus are explained, which creates stress for many people and makes them avoid all news about the virus (Savage, 2020).

3. Results and discussion

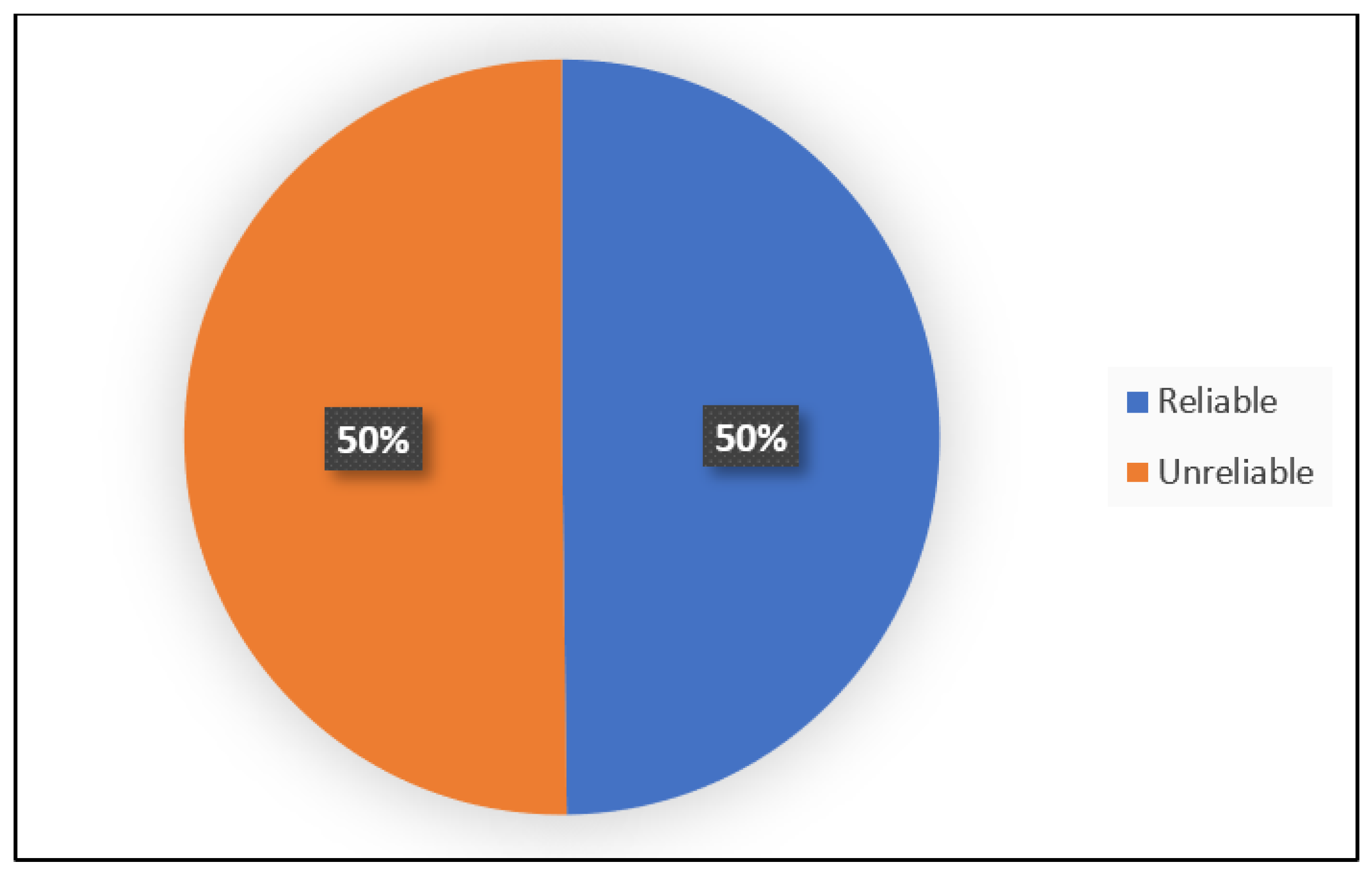

At the very beginning of the research, respondents were asked whether they think social media is effective in reporting disasters to the public, whether there are obstacles in reporting, and whether social media is susceptible to false reporting. Respondents were also asked to rate the effectiveness of social media in disaster reporting. The results show that an almost identical number of answers were "no" (50.2%) and "yes" (49.8%) (

Figure 1).

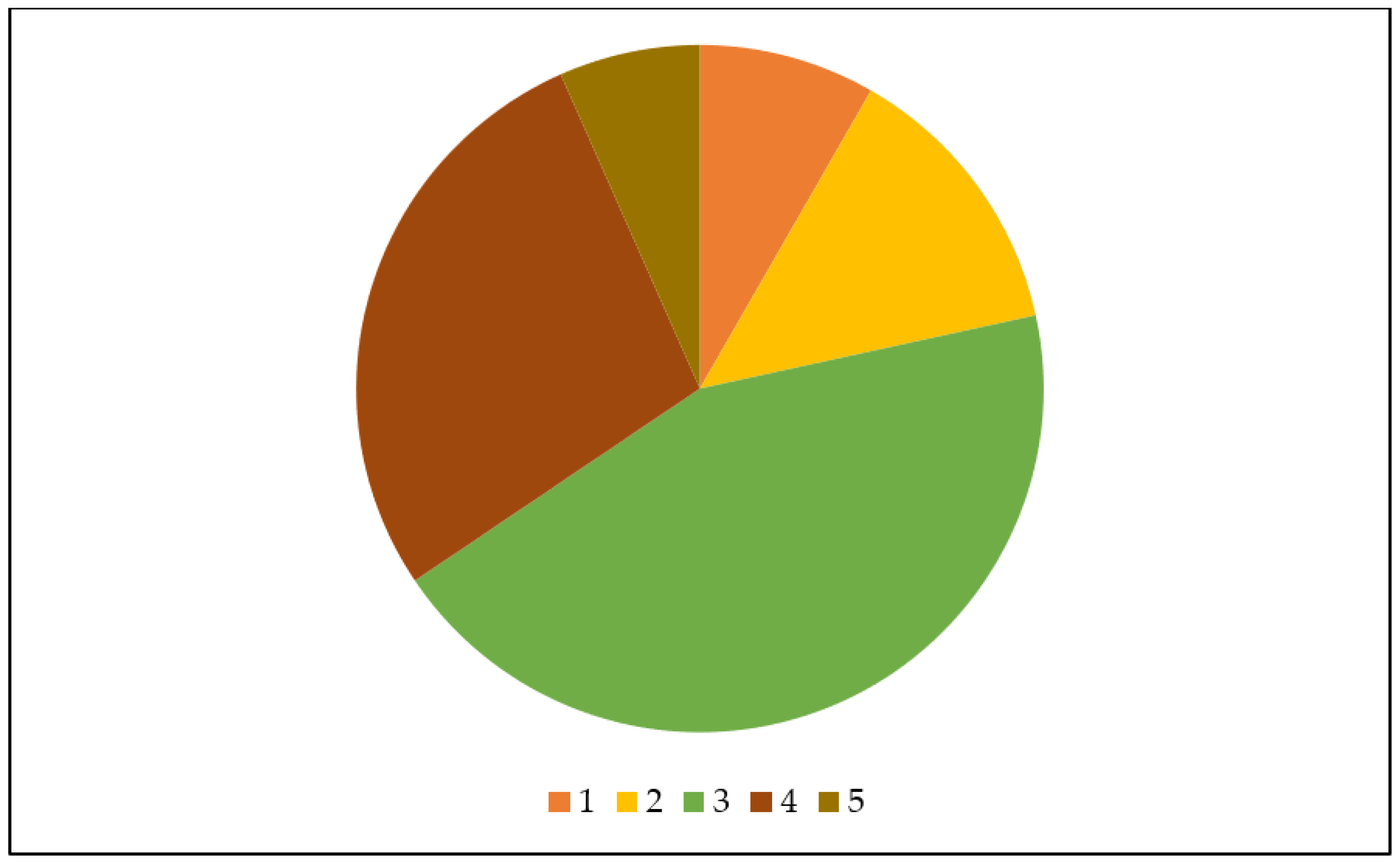

Further analysis shows that 38.5% of respondents believe that there are obstacles, while 61.5% of respondents believe that there are no obstacles in social media reporting on disasters. When it comes to false reporting of disasters by individuals, 74.5% of respondents believe that they are susceptible, while only 25.5% of respondents believe that they are not. When it comes to assessing the effectiveness of social media, 44% of respondents consider that they are neither effective nor ineffective, while 34% of respondents consider that they are effective in the process of informing the public about the risks of disasters (

Figure 2).

The results of the Chi-square test (x2) show that there is no statistically significant relationship between the level of education of the respondents and the rating of the effectiveness of social media reporting on disasters. Regarding the question of whether there are obstacles in social media reporting on natural disasters, respondents with secondary education (41.1%) answered "yes", while respondents with higher education answered "no" the most (43.4% ). It was determined that there is no statistically significant relationship between the level of education of respondents and the opinion of whether there are obstacles in social media reporting on natural disasters.

When asked whether social networks are susceptible to false reporting, respondents with primary education (83.3%) mostly answered "yes", while respondents with secondary education (28.4%) mostly answered "no". Also, it was determined that there is no statistically significant connection between the level of education of respondents and the opinion of whether social networks are susceptible to false reporting. In this research, a comparison of the demographic characteristics of the respondent's place of residence with their attitude about the effectiveness of social media in informing the public about disasters was also carried out. The results show that there is no statistically significant relationship between these two variables.

Through further analyses, it was determined that there is no statistically significant connection between the place of residence and the attitude that there are obstacles in social media reporting. Further results show that there is a statistically significant relationship between respondents' exposure to a natural disaster and the attitude that there are certain obstacles in social media reporting on natural disasters. It was also determined that there is no statistically significant connection between the respondents' exposure to a natural disaster and the opinion that social networks are susceptible to false reporting by individuals about natural disasters. In addition, it was determined that there is no statistically significant connection between the respondents' exposure to a disaster and the evaluation of the efficiency of the media in informing about natural disasters. The research aimed to examine the views of the citizens of the Republic of Serbia on the role of social media in the process of informing the public about the existing risks of disasters. The research sample, which was conducted electronically, included a total of 247 respondents in Serbia. To the greatest extent, the sample consisted of women (56.3%), citizens aged 18-30 years (37.7%), living in an urban environment (80.6%), having medium (38.5%) and higher education (38.5%) and are not in an emotional relationship (47.8%). Also, the share of employed and unemployed respondents in the sample structure is almost equal.

When examining respondents' views on the reliability of social media as a source of information about natural disasters, no unified view was found. The results divided in this way can be related to the research findings conducted by Williams and colleagues (2018), which indicate that citizens consider family and friends to be the most reliable sources of information. However, if only official organizations (eg local emergency officials) are considered as a source of information through social media, the likelihood of using social media as a reliable source of information is much higher. In addition, Xu et al. (2021) postulate that trust is closely related to the perceived risk level of natural disasters.

Furthermore, bearing in mind the dizzying expansion of the infodemic that follows the modern era, the respondents' perception of the susceptibility of social networks to false reporting on natural disasters was investigated. On that occasion, it was determined that as many as 74.5% of respondents included in the sample rate vulnerability was significant. This confirmed the results of the research conducted by Ghosh et al. (2018), who indicate that a larger share of the population believes that social networks are prone to and susceptible to the spread of misinformation. It was concluded that at the time of the disaster, there was widespread panic and tension among the people. The authors also note that detecting misinformation and rumours on social media during disaster reporting is a significant challenge, as at such times even genuinely famous people may also unwittingly publish rumours.

In addition, disaster reporting and "curation" by unknown individuals and organizations can raise concerns about information accuracy, the potential for rumour, malicious use (such as social media hoaxes), and privacy protection (Taylor et al., 2012). The majority of the respondents of this research believe that increased control of information and greater punishment of those who spread false information can reduce its harmful effect, while Ghosh et al. (2018) believe that combining information from multiple sources can be a good way to identify misinformation, as well as that methods must be developed to detect harmful content on social networks, and then to effectively deal with them.

When it comes to the importance of adequate communication between the local government and the community, our results support the findings of a survey (Collett, 2014) conducted at Eastern Kentucky University, in which it was found that 54.05% of respondents agree and 24.32% absolutely largely agree (78.37%) that local governments should use social media to communicate with the community about issues and emergencies that have a direct impact on the community. A similar result is present in this research; 83.4% of respondents agree, while 16.6% disagree. Also, in the previously mentioned survey, it was determined that 92.11% of respondents have access to the Internet, which also coincides with the results of this survey (99.2%). The high percentage of Internet access shows how the development of information technologies has influenced various aspects of disaster risk management. While the number of social media users continues to grow globally, these platforms are relatively in their infancy. Instant gratification, which users can experience interacting with their peers on different levels, brings an appeal that cannot be found in other forms of modern communication (Collett, 2014).

However, contrary research (Collett, 2014) indicates that 50% of respondents agree and 23.68% strongly agree (73.68%) about tending to read others' posts when the topic is related to current and potential disasters or emergencies, the results of this research produced different results. Namely, 76.9% of the respondents stated that they do not regularly monitor social media reports on potential natural disasters, while 23.1% stated that they do. An informed and prepared population can be more resilient to a disaster, so there are efforts by individuals and organizations to learn how to prepare for a disaster, and organizations and governments to spread the content of disaster preparedness in the country, which can be of great benefit to people and communities (Houston et al., 2015). Disaster social media can help this process by connecting individuals and organizations with disaster preparedness information before a disaster strikes. The results of this research show that a very small percentage of respondents adequately prepared themselves by informing themselves before the disaster and avoided certain material/health damage caused by the disaster (28.3%), while 71.7% of respondents pointed out that they failed to prepare adequately by informing themselves through social media.

During and immediately after a disaster, people will want to know if family and friends in the affected area are safe. Moreover, if the level of destruction is high, individuals will often need a place to check in, inform others about their condition and establish connections with others, the role of social media in these processes not being negligible (Houston et al., 2015). To the question "Have you participated in any reporting on natural disasters via social media?", a large number of respondents (82.6%) answered that they had not, and 17.4% that they had. Given that 67.6% of respondents were exposed to some kind of disaster, and 32.4% were not, it can be concluded that it is necessary to further develop appropriate mechanisms and tools that would enable easier communication in emergencies caused by disasters. It is very important to invest efforts in local public organizations in the direction of building trust among the public so that critical information can be effectively disseminated and citizens can easily access it during a catastrophe through social media. This ultimately increases the effectiveness of disaster response and assistance. It is important to mention the increase in the use of smartphones, as one of the more significant factors contributing to the spread and greater influence of social media in disaster reporting (Taylor et al., 2012). It can be safely concluded that social media in the context of disasters, although in any other context, are characterized by both bright and dark sides.

3. Conclusions

Media in modern society is characterized by a high level of connectivity and the progressive development of information and communication technologies. Social media informs the public about the most important events and conveys important information. Before, during and after disasters, social media are used to disseminate information about disasters and to gather data relevant to the implementation of preparedness, response and recovery activities and measures. Social networks are effective in disseminating information and warnings, as well as in educating the public. At the same time, they are a source of information for decision-makers, based on which they can monitor the course of disasters, their consequences, public opinion and the needs of citizens. However, to use social networks in the best possible way, it is necessary to have the knowledge, advanced technologies and resources.

However, information about disasters that are sensationalist can also have negative effects. Too often news broadcasts and the way they are conveyed can increase fear among citizens, and cause anxiety, stress and depression. Social media, characterized by interactivity and the transmission of content created by the users of social networks themselves, are a rich source of inaccurate information. This information does not have to be objective or accurate, but it is generally available to the public faster than verified and reliable information, which is transmitted through other communication channels. The spread of misinformation and other people's opinions contributes to increasing uncertainty and fear among citizens. Social networks are often used as a source of information today. Citizens often do not check the sources of information and tend to form opinions based on short information, headlines, images and video content. This can lead to overexposure to news that is unverified and subjective, and to citizen distrust and often resistance to government disaster mitigation measures. Also, misinformation and half-information that is often present on the Internet can directly threaten human health and create distrust of citizens in governments and experts. Therefore, timely and accurate information, as well as the use of appropriate tools that enable this, is a basic prerequisite for successful disaster management.

The conducted research generates new research questions in which we should further investigate and study various demographic factors that influence the process of informing about the risks of disasters through social media, and that influence the design and implementation of appropriate strategies and innovative solutions in this area. Given that the study and understanding of the social context, that is, the perception, beliefs and attitudes of citizens, which shape the way they interpret and respond to information, is of key importance for decision-makers, the implications of the research have practical significance. The limitations of the conducted research are, on the other hand, the coverage of a smaller territorial area and population of the Republic of Serbia.