Submitted:

26 January 2023

Posted:

26 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design & Population

2.2. Sample Size and sampling strategy

2.3. Study tools

2.4. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

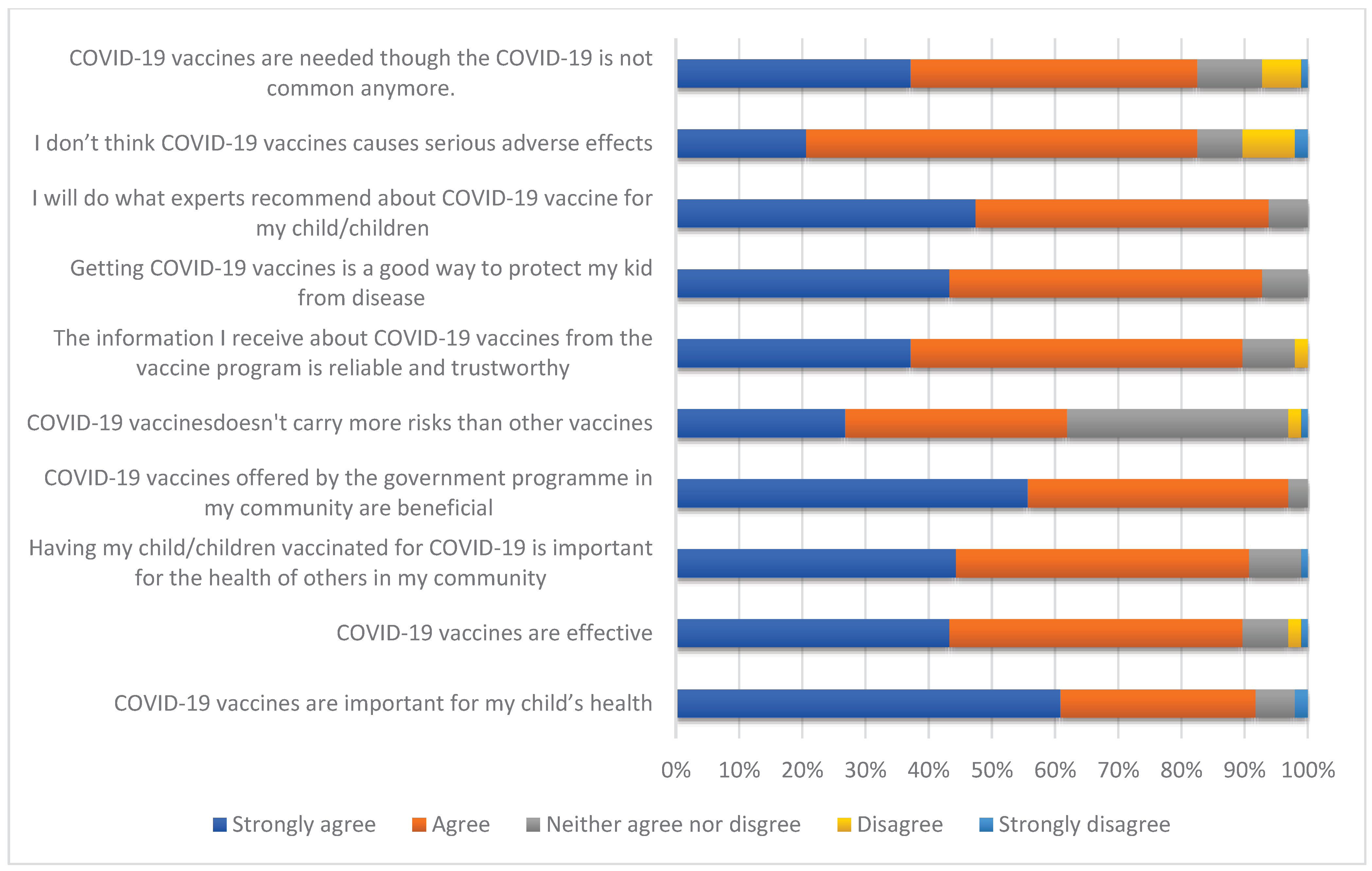

Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS)—Attitude towards the Importance of Vaccinating Children against COVID-19

| Variables | Willing to vaccine the child N(%) |

Not willing to vaccinate the child N(%) |

X2* -value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age-group ( in years) 18-39 ≥ 40 years |

176(95.7) 180(88.2) |

8(4.3) 24(11.8) |

7.03 |

0.008* |

|

Gender Male Female |

128(84.2) 228(96.6) |

24(15.8) 8(3.4) |

18.8 |

0.00001* |

|

Religion Hindu Non-Hindu |

316(91.7) 40(90.9) |

28(8.3) 4(9.1) |

0.004 |

0.83 |

|

Marital status Currently married Widowed/divorced/separated |

352(92.6) 4(50.0) |

28(7.4) 4(50.0) |

18.8 |

0.00001* |

|

Education level Below graduate Graduate and above |

164(93.2) 192(90.6) |

12(6.8) 20(9.4) |

0.86 |

0.35 |

|

Occupation Doctor Nurse/Technician/Others |

112(90.3) 244(92.4) |

12(9.7) 20(7.6) |

0.49 |

0.48 |

|

Place of residence Urban Rural |

216(94.7) 140(87.5) |

12(5.3) 20(12.5) |

6.5 |

0.01* |

|

Monthly income (in INR) <10,000 ≥ 10,000 |

156(95.1) 200(89.3) |

8(4.9) 24(11.7) |

4.26 |

0.03* |

|

Presence of any chronic illness in participant Yes No |

24(75.0) 332(93.2) |

8(25.0) 24(6.8) |

12.93 |

0.0003* |

|

History of Lab confirmed COVID-19 in participant Present Absent |

172(89.6) 184(93.9) |

20(11.4) 12(6.1) |

2.36 |

0.12 |

|

History of hospitalization due to COVID-19 Present Absent |

12(100.0) 344(91.5) |

0(0.0) 32(8.5) |

- |

0.7 |

|

Self COVID-19 vaccination status Taken 2 or more doses Taken 1 dose only/not vaccinated |

344(91.5) 12(100.0) |

32(8.5) 0(0.0) |

- |

0.7 |

|

History of any adverse event post COVID-19 vaccination Present Absent |

116(93.5) 240(90.9) |

8(6.5) 24(8.1) |

0.77 |

0.38 |

|

History of any child testing positive for COVID-19 Present Absent |

32(80.0) 324(93.1) |

8(20.0) 24(6.9) |

8.14 |

0.004* |

|

The child/ren up-to-date with routine childhood vaccines Yes No/Not sure |

320(93.0) 36(81.8) |

24(7.0) 8(18.2) |

6.47 |

0.01* |

4. Discussion

Strengths & Limitations

5. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/in (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- ` Delahoy MJ, Ujamaa D, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, Anglin O, Burns E, et al. Hospitalizations associated with COVID-19 among children and adolescents—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1, 2020–August 14, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021, 70, 1255–1260. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interim statement on COVID-19 vaccination for children and adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-11-2021-interim-statement-on-covid-19-vaccination-for-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for Children. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/planning/children.html (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Ioannidis JPA. COVID-19 vaccination in children and university students. Eur J Clin Investig ation 2021, 51.

- Olson SM, Newhams MM, Halasa NB, Price AM, Boom JA, Sahni LC, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against critical Covid-19 in adolescents. N. Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, F. Shen K. COVID-19 in children and the importance of COVID-19 vaccination. World J. Pediatr. 2021, 17, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano LD, Newhams MM, Olson SM, Halasa NB, Price AM, Boom JA. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA Vaccination Against Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Among Persons Aged 12-18 Years - United States, July-December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022, 71, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klass P, Ratner AJ. Vaccinating children against covid-19 - the lessons of measles. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1969–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3 Vaccines Get Emergency Approval For Children. Available online: https://www.india.com/news/india/vaccine-for-kids-3-vaccines-get-emergency-approval-for-children-zycov-d-corbevax-covaxin-dcgi-green-signal-read-details-5358986/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- The Times of India. Beneficiaries in 15-18 yrs age group to start getting 2nd dose. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/beneficiaries-in-15-18-yrs-age-group-to-start-getting-2nd-dose-of-covid-vaccine-from-monday/articleshow/89229669.cms (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- MacDonald, N.E. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine. 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Health Issues WHO Will Tackle This Year. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Domek, GJ, O’Leary ST, Bull S, Bronsert M, Contreras-Roldan IL, Bolaños Ventura GA, et al. Measuring Vaccine Hesitancy: Field Testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Survey Tool in Guatemala. Vaccine. 2018, 35, 5273–5281. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram, S, Schuster M. Mapping Vaccine Hesitancy—Country-Specific Characteristics of a Global Phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen YQ, et al. Parental Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children Under the Age of 18 Years: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, Thomas K, Vizueta N, Cui Y, et al. Parents’ Intentions and Perceptions About COVID-19 Vaccination for Their Children: Results From a National Survey. Pediatrics. 2021, 148, e2021052335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humble RM, Sell H, Dubé E, MacDonald NE, Robinson J, Driedger SM, et al. Canadian parents’ perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination and intention to vaccinate their children: Results from a cross-sectional national survey. Vaccine. 2021, 39, 7669–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammershaimb EA, Cole LD, Liang Y, Hendrich MA, Das D, Petrin R, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among US Parents: A Nationally Representative Survey. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022, 11, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee M, Seo S, Choi S, Park JH, Kim S, Choe YJ, et al. Parental Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children and Its Association With Information Sufficiency and Credibility in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e2246624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou Z, Song K, Wang Q, Zang S, Tu S, Chantler T, Larson HJ. Childhood COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and preference from caregivers and healthcare workers in China: A survey experiment. Prev Med. 2022, 161, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKetbi LMB, Al Hosani F, Al Memari S, et al. Parents’ views on the acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine for their children: A cross-sectional study in Abu Dhabi-United Arab Emirates. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 5562–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li JB, Lau EYH, Chan DKC. Why do Hong Kong parents have low intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19? testing health belief model and theory of planned behavior in a large-scale survey. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco A, Della Polla G, Angelillo S, Pelullo CP, Licata F, Angelillo IF. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional survey in Italy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022, 21, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M, Sahin, MK. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021, 75, e14364. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed AH, Hassan BAR, Wayyes AM, Gadhban AQ, Blebil A, Alhija SA, Darwish RM, Al-Zaabi AT, Othman G, Jaber AAS, Al Shouli BA, Dujaili J, Al-Ani OA, Muthanna FMS. Parental health beliefs, intention, and strategies about COVID-19 vaccine for their children: A cross-sectional analysis from five Arab countries in the Middle East. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 6549–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan YH, Rasheed M, Mallhi TH, Salman M, Alzarea AI, Alanazi AS, Alotaibi NH, Khan SU, Alatawi AD, Butt MH, Alzarea SI, Alharbi KS, Alharthi SS, Algarni MA, Alahmari AK, Almalki ZS, Iqbal MS. Barriers and facilitators of childhood COVID-19 vaccination among parents: A systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2022, 10, 950406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin Shen, Hao Dong, Jing Feng, Heng Jiang, Rowan Dowling, Zuxun Lu, Chuanzhu Lv & Yong Gan. Assessing the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Chinese adults using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2021, 17, 4005–4012. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue; Ma 02115 +1495-1000 Barry, R. Bloom’s Faculty Website. Available online: https://www.hsph. harvard.edu/barry-bloom/.

- Orenstein WA, Ahmed R. Simply put: Vaccination saves lives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017, 114, 4031–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trogen B, Pirofski LA. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in COVID-19. Med (N Y). 2021, 2, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Razai M S, Chaudhry U A R, Doerholt K, Bauld L, Majeed A. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ 2021, 373, n1138. [Google Scholar]

- Toth-Manikowski SM, Swirsky ES, Gandhi R, Piscitello G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am J Infect Control. 2022, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandani S, Jani D, Sahu PK, Kataria U, Suryawanshi S, Khubchandani J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in India: State of the nation and priorities for research. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021, 18, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi BK, Satapathy P, Rajagopal V, Rustagi N, Vij J, Jain L, et al. Parents’ Perceptions and Intention to Vaccinate Their Children Against COVID-19: Results From a Cross-Sectional National Survey in India. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 806702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan R, Pandey V, Kumar A, Gangadevi P, Goel AD, Joseph J, et al. Acceptance and Attitude of Parents Regarding COVID-19 Vaccine for Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2022, 14, e24518. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar P, Chandrasekaran V, Gunasekaran D, Chinnakali P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care worker-parents (HCWP) in Puducherry, India and its implications on their children: A cross sectional descriptive study. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 5821–5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himanshi, KADAM KS, Uttarwar PU. COVID-19 VACCINE HESITANCY FOR CHILDREN IN PARENTS: A CROSS-SECTIONAL SURVEY AMONG HEALTH-CARE PROFESSIONALS IN INDIA. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2022, 15, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus J, Wyka K, White T, Picchio C, Gostin L, Larson H, et al. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nature Medicine 2023, 1–10.

- Zhou X, Wang S, Zhang K, Chen S, Chan PS, Fang Y, et al. Changes in Parents’ COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Children Aged 3-17 Years before and after the Rollout of the National Childhood COVID-19 Vaccination Program in China: Repeated Cross-Sectional Surveys. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shati AA, Al-Qahtani SM, Alsabaani AA, Mahmood SE, Alqahtani YA, AlQahtani, KM, et al. Perceptions of Parents towards COVID-19 Vaccination in Children, Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit M, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 Vaccine Refusal in Parents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021, 40, e134–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age-groups( in years) 18-29 years 30-39 40-49 50-59 ≥ 60 |

04 180 172 24 08 |

1.0 46.4 44.3 6.3 2.0 |

|

Gender Male Female |

152 236 |

39.2 60.8 |

|

Religion Hindu Muslim Christian Others |

344 24 12 8 |

88.6 6.2 3.1 2.1 |

|

Marital status Currently married Widowed/Divorced/Separated |

380 08 |

97.9 2.1 |

|

Place of residence Urban Rural |

228 160 |

58.8 41.2 |

|

Highest level of Education Up to Matriculation Intermediate (10+2)/Diploma Graduate Postgraduate & Above |

156 20 108 104 |

40.2 5.1 26.8 27.8 |

|

Designation Doctor Nursing officer/Technician OPD/Ward/Lab/Sanitary attendant Security staff |

124 80 164 16 |

32.0 20.6 42.3 4.1 |

|

Monthly income(in INR) <10,000 10,000-49,999 50,000-99,999 ≥100,000 |

164 108 40 76 |

42.3 27.8 10.3 19.6 |

|

History of any chronic illness Present Absent |

32 356 |

91.7 8.3 |

|

History of Lab confirmed COVID-19 infection Yes No |

192 196 |

49.5 51.5 |

|

History of Hospitalization due to COVID-19 Yes No No history of COVID-19 |

12 180 196 |

6.3 43.2 51.5 |

|

COVID-19 Vaccination status Received 2 doses & 1 booster dose Received 2 doses Received 1 dose Not vaccinated |

292 84 8 4 |

75.3 21.6 2.1 1.0 |

|

History of any adverse event post COVID-19 vaccine Present Absent |

124 264 |

31.9 68.1 |

|

Primary source of information for COVID-19 vaccine Workplace Traditional media (TV, Radio, Newspaper) Social & Online Media Family & friends |

212 100 64 12 |

54.6 25.8 16.5 3.1 |

|

History of any child testing positive for COVID-19 Present Absent |

40 348 |

10.3 89.7 |

|

Distribution of participants by no. of child(<18 years) Have 1 child Have 2 child Have 3 child |

188 132 68 |

48.4 43.3 33.0 |

|

Age-groups of the children(in years) 12-17 <12 |

312 294 |

51.5 48.5 |

|

Gender of the children Male Female |

346 260 |

57.1 42.1 |

|

History of any child testing positive for COVID-19 Present Absent |

40 348 |

10.3 89.7 |

|

The child/children up-to-date with routine childhood vaccines Yes No/Not sure |

344 42 |

88.7 11.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).