Submitted:

23 January 2023

Posted:

27 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

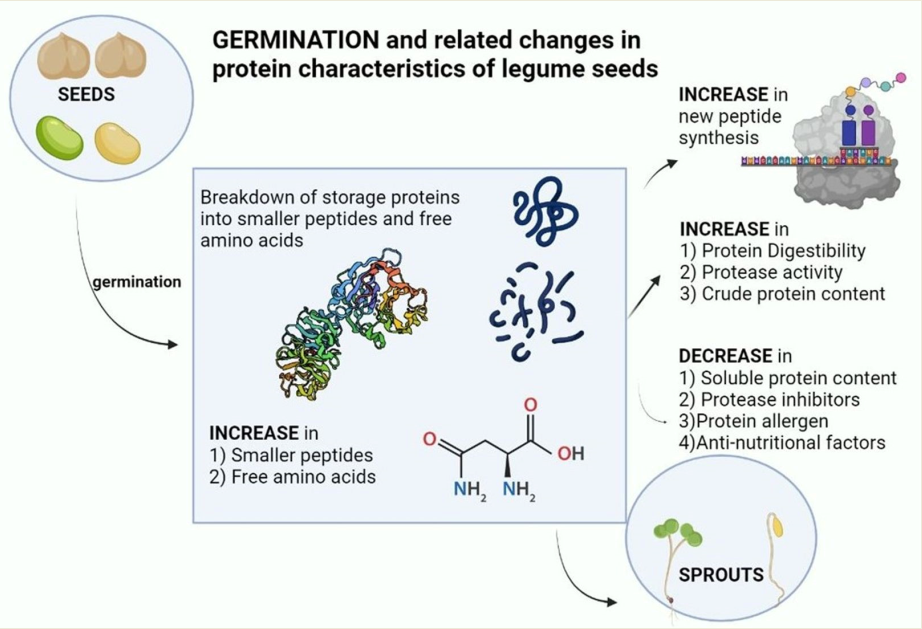

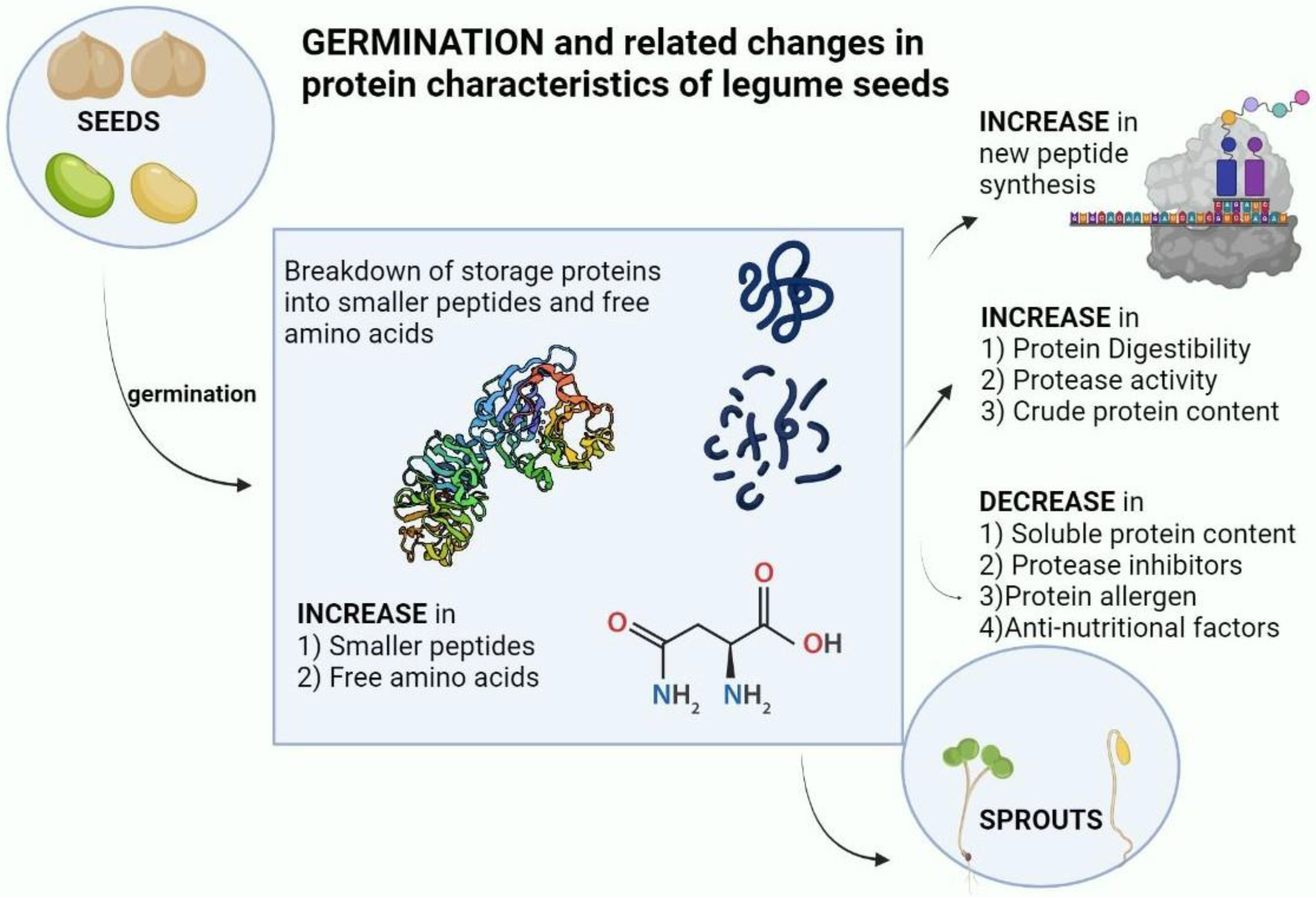

2. Plant Proteins and their alterations during germination

2.1. Changes in crude protein content during germination

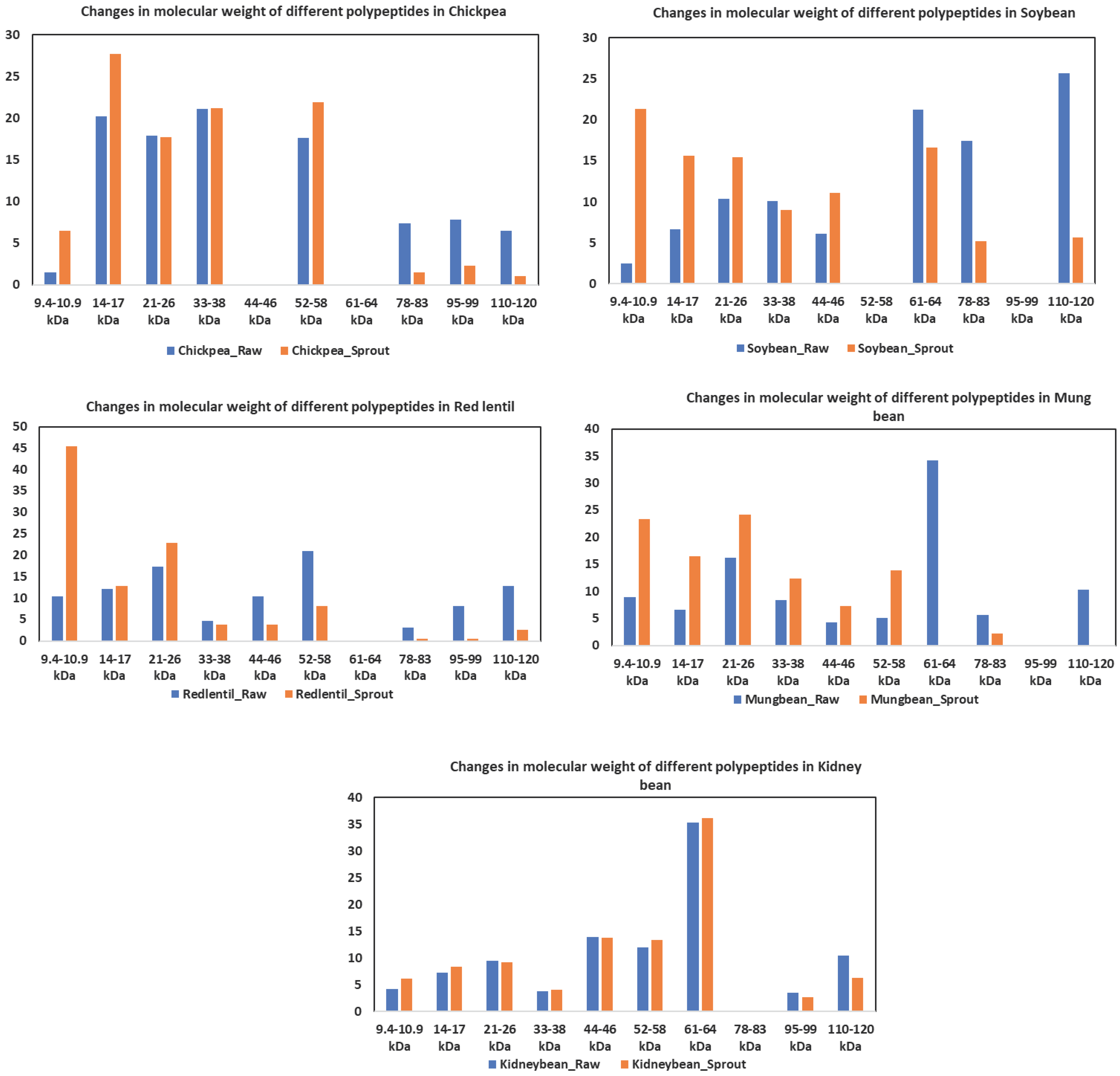

2.2. Changes in polypeptide molecular weight distributions during germination

2.3. Storage protein changes during germination

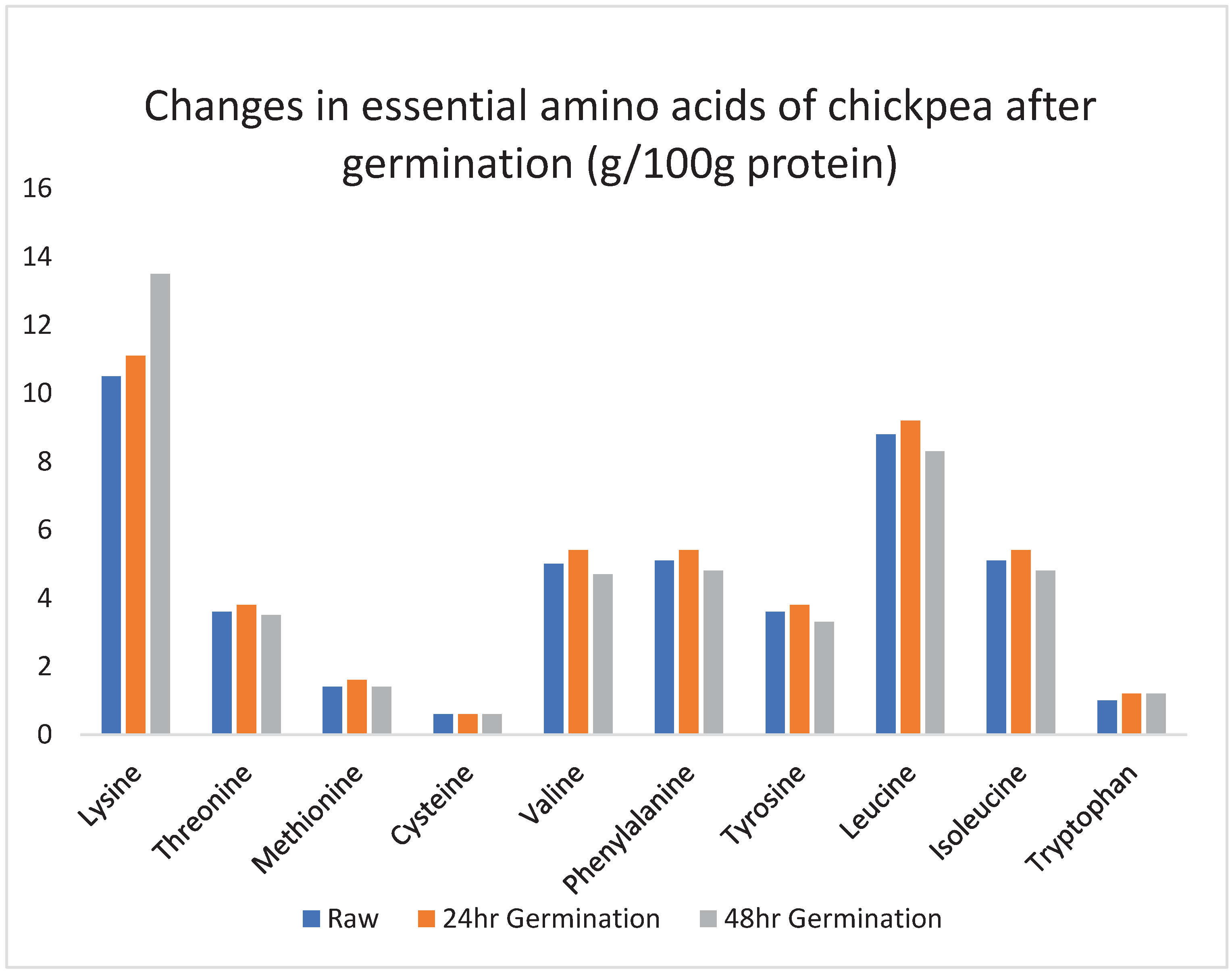

2.4. Changes in free amino acids and protein amino acids during legume germination

3. Changes in protein digestibility during legume germination

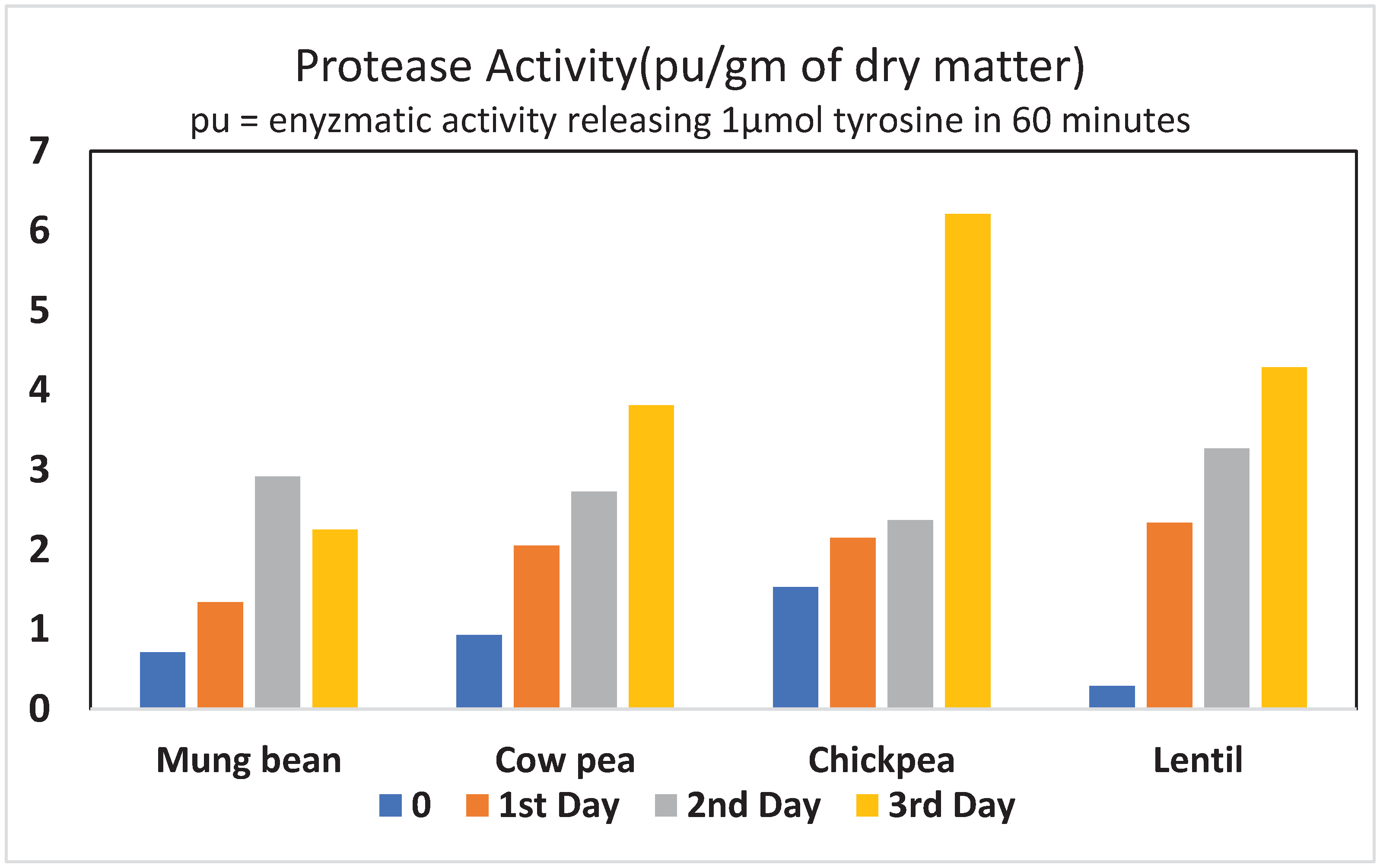

4. Changes in proteases during legume germination.

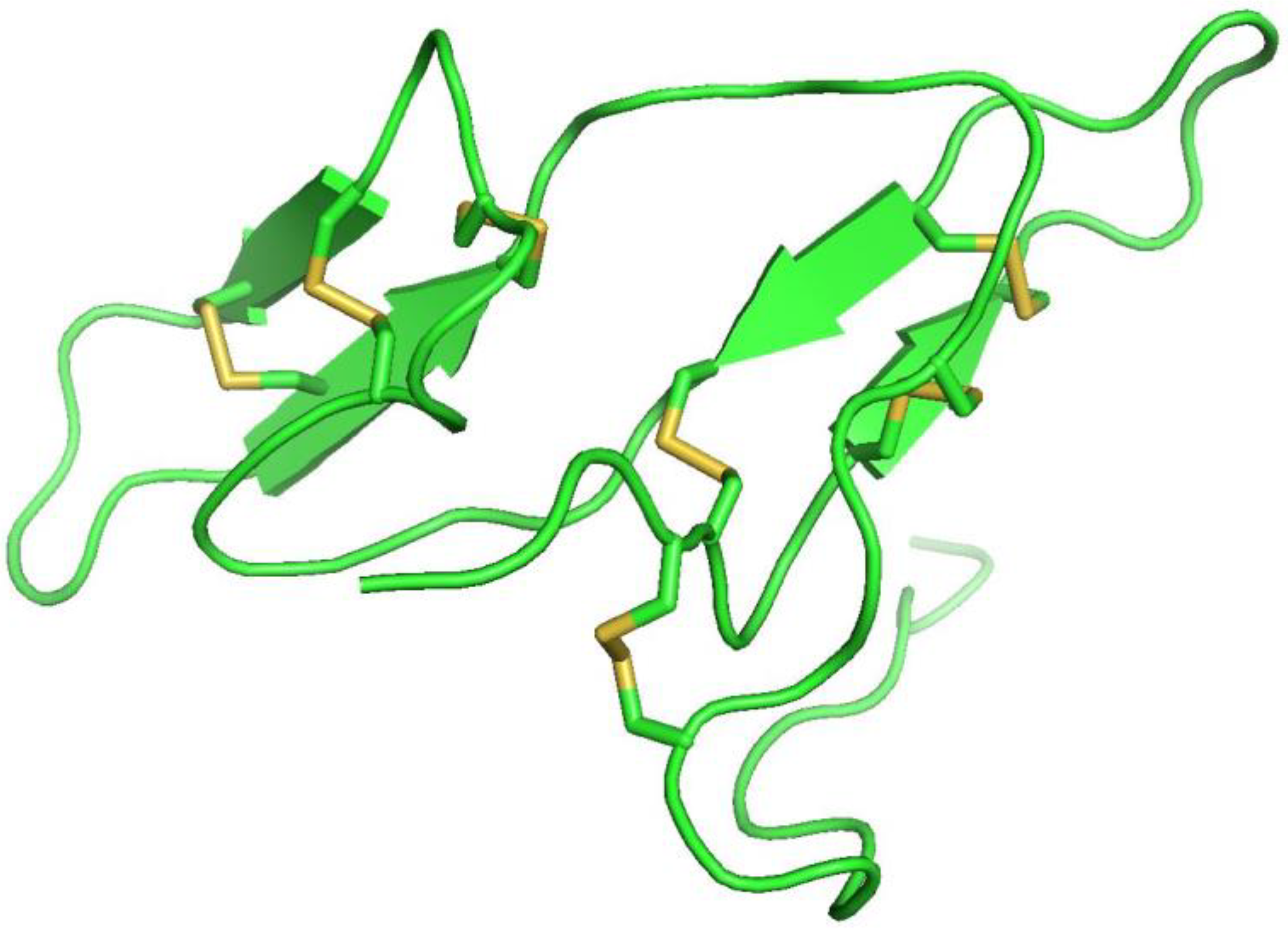

5. Changes in protease inhibitors during legume germination

6. Changes in protein allergens during germination

7. Impact of food processing on protein digestibility

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nadathur, S.R.; Wanasundara, J.P.D.; Scanlin, L. Proteins in the diet: Challenges in feeding the global population. In Sustainable protein sources; Academic Press, 2017; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.D. Starchy legumes in human nutrition, health and culture. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1993, 44, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, L. Proteins from land plants–potential resources for human nutrition and food security. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2013, 32, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O.G. Recent advances in the functionality of non-animal-sourced proteins contributing to their use in meat analogs. Current Opinion in Food Science 2016, 7, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnen, R.T.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Slavin, J.L. Role of plant protein in nutrition, wellness, and health. Nutrition reviews 2019, 77, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gepts, P.; Beavis, W.D.; Brummer, E.C.; Shoemaker, R.C.; Stalker, H.T.; Weeden, N.F.; Young, N.D. Legumes as a model plant family. Genomics for food and feed report of the cross-legume advances through genomics conference. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barać, M.; Čabrilo, S.; Pešić, M.; Stanojević, S.; Pavlićević, M.; Maćej, O.; Ristić, N. Functional properties of pea (Pisum sativum, L.) protein isolates modified with chymosin. International journal of molecular sciences 2011, 12, 8372–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pace, C.; Delre, V.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.T.; Maggini, F.; Cremonini, R.; Frediani, M.; Cionini, P.G. Legumin of Vicia faba major: accumulation in developing cotyledons, purification, mRNA characterization and chromosomal location of coding genes. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1991, 83, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, J.; Zare, F.; Pletch, A. Pulse proteins: Processing, characterization, functional properties and applications in food and feed. Food research international 2010, 43, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Oomah, B.D. Minor components of pulses and their potential impact on human health. Food research international 2010, 43, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, V.; Bains, K. Effect of germination periods and hydrothermal treatments on in vitro protein and starch digestibility of germinated legumes. Journal of food science and technology 2012, 49, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, D. Digestibility issues of vegetable versus animal proteins: protein and amino acid requirements—functional aspects. Food and nutrition bulletin 2013, 34, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsma, M.A.; Bolter, C. The adaptation of insects to plant protease inhibitors. Journal of Insect Physiology 1997, 43, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu-Salzman, K.; Zeng, R. Insect response to plant defensive protease inhibitors. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2015, 60, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonaro, M.; Maselli, P.; Nucara, A. Structural aspects of legume proteins and nutraceutical properties. Food Research International 2015, 76, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.S.; DAMODARAN, S. Structure-digestibility relationship of legume 7S proteins. Journal of Food Science 1989, 54, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, M.; Maselli, P.; Nucara, A. Relationship between digestibility and secondary structure of raw and thermally treated legume proteins: a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic study. Amino acids 2012, 43, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müntz, K. Proteases and proteolytic cleavage of storage proteins in developing and germinating dicotyledonous seeds. Journal of Experimental Botany 1996, 47, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.D.; Volpicella, M.; Licciulli, F.; Liuni, S.; Gallerani, R.; Ceci, L.R. PLANT-PIs: a database for plant protease inhibitors and their genes. Nucleic acids research 2002, 30, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossé, J.; Baudet, J. Crude protein content and aminoacid composition of seeds: variability and correlations. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1983, 32, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Napier, J.A.; Tatham, A.S. Seed storage proteins: structures and biosynthesis. The plant cell 1995, 7, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.B. The vegetable proteins; Longmans, Green and Company, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemede, H.F.; Ratta, N. Antinutritional factors in plant foods: Potential health benefits and adverse effects. International journal of nutrition and food sciences 2014, 3, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, S.G.; Ayua, E.; Kamau, E.H.; Shingiro, J.B. Fermentation and germination improve nutritional value of cereals and legumes through activation of endogenous enzymes. Food science & nutrition 2018, 6, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Jin, Z.; Simsek, S.; Hall, C.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Effect of germination on the chemical composition, thermal, pasting, and moisture sorption properties of flours from chickpea, lentil, and yellow pea. Food Chemistry 2019, 295, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.D.; Bubolz, V.K.; da Silva, J.; Dittgen, C.L.; Ziegler, V.; de Oliveira Raphaelli, C.; de Oliveira, M. Changes in the chemical composition and bioactive compounds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) fortified by germination. LWT 2019, 111, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipnaik, K.; Bathere, D. Effect of soaking and sprouting on protein content and transaminase activity in pulses. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2017, 5, 4271–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, E.H. Biological and chemical evaluation of chick pea seed proteins as affected by germination, extraction and α-amylase treatment. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1996, 49, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.W.; Zeb, A.; Mahmood, F.; Tariq, S.; Khattak, A.B.; Shah, H. Comparison of sprout quality characteristics of desi and kabuli type chickpea cultivars (Cicer arietinum L.). LWT-Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Sharanagat, V.S.; Singh, L.; Mani, S. Effect of germination and roasting on the proximate composition, total phenolics, and functional properties of black chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Legume Science 2020, 2, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Varma, K. Effect of germination and dehulling on the nutritive value of soybean. Nutrition & Food Science 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayembe, N.C.; van Rensburg, C.J. Germination as a processing technique for soybeans in small-scale farming. South African Journal of Animal Science 2013, 43, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassegn, H.H.; Atsbha, T.W.; Weldeabezgi, L.T. Effect of germination process on nutrients and phytochemicals contents of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) for weaning food preparation. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2018, 4, 1545738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Gulewicz, P.; Frias, J.; Gulewicz, K.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Assessment of protein fractions of three cultivars of Pisum sativum L.: effect of germination. European Food Research and Technology 2008, 226, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasevičienė, Ž.; Danilčenko, H.; Jariene, E.; Paulauskienė, A.; Gajewski, M. Changes in some chemical components during germination of broccoli seeds. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2009, 37, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moongngarm, A.; Saetung, N. Comparison of chemical compositions and bioactive compounds of germinated rough rice and brown rice. Food chemistry 2010, 122, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamilla, R.K.; Mishra, V.K. Effect of germination on antioxidant and ACE inhibitory activities of legumes. Lwt 2017, 75, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temba, M.C.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adebo, O.A.; Olugbile, A.O.; Kayitesi, E. The role of compositing cereals with legumes to alleviate protein energy malnutrition in Africa. International journal of food science & technology 2016, 51, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L.A.; Pérez, A.; Ruiz, R.; Guzmán, M.Á.; Aranda-Olmedo, I.; Clemente, A. Characterization of pea (Pisum sativum) seed protein fractions. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2014, 94, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennetau-Pelissero, C. Plant proteins from legumes. In Bioactive molecules in food; Springer: Cham, 2019; pp. 223–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, F.; Boye, J.I.; Simpson, B.K. Bioactive proteins and peptides in pulse crops: Pea, chickpea and lentil. Food research international 2010, 43, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Hillen, C.; Garden Robinson, J. Composition, nutritional value, and healthbenefits of pulses. Cereal Chemistry 2017, 94, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fuentes, C.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Recio, I.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J. Identification and characterization of antioxidant peptides from chickpea protein hydrolysates. Food Chemistry 2015, 180, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portari, G.V.; Tavano, O.L.; Silva, M.A.D.; Neves, V.A. Effect of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) germination on the major globulin content and in vitro digestibility. Food Science and Technology 2005, 25, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacrés, E.; Allauca Chávez, V.V.; Peralta, E.; Insuasti, G.; Álvarez, J.; Quelal, M.B. Germination, an effective process to increase the nutritional value and reduce non-nutritive factors of lupine grain (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet). 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Gulewicz, P.; Frias, J.; Gulewicz, K.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Assessment of protein fractions of three cultivars of Pisum sativum L.: effect of germination. European Food Research and Technology 2008, 226, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, A.E.M.M.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Abd El-Salam, S.M.; Omran, A.A. Protein solubility, digestibility and fractionation after germination of sorghum varieties. Plos one 2012, 7, e31154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozan, P.; Kuo, Y.H.; Lambein, F. Amino acids in seeds and seedlings of the genus Lens. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.L.; Berry, J.W. Nutritional evaluation of chickpea and germinated chickpea flours. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1988, 38, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.H.; Rozan, P.; Lambein, F.; Frias, J.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Effects of different germination conditions on the contents of free protein and non-protein amino acids of commercial legumes. Food chemistry 2004, 86, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, A.G.A.; Moreno, Y.M.F.; Carciofi, B.A.M. Food processing for the improvement of plant proteins digestibility. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2020, 60, 3367–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma, G. The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS)—a concept for describing protein quality in foods and food ingredients: a critical review. Journal of AOAC International 2005, 88, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büchmann, N.B. In vitro digestibility of protein from barley and other cereals. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 1979, 30, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, U.; Singh, U.; Venkateswara Rao, P. Phytic acid, in vitro protein digestibility, dietary fiber, and minerals of pulses as influenced by processing methods. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1996, 49, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghavidel, R.A.; Prakash, J. The impact of germination and dehulling on nutrients, antinutrients, in vitro iron and calcium bioavailability and in vitro starch and protein digestibility of some legume seeds. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpanadevi, V.; Mohan, V.R. Effect of processing on antinutrients and in vitro protein digestibility of the underutilized legume, Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp subsp. unguiculata. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2013, 51, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimelis, E.A.; Rakshit, S.K. Effect of processing on antinutrients and in vitro protein digestibility of kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties grown in East Africa. Food chemistry 2007, 103, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, R.; Dai, Z.; Nickerson, M.T.; Sopiwnyk, E.; Malcolmson, L.; Ai, Y. Impacts of short-term germination on the chemical compositions, technological characteristics and nutritional quality of yellow pea and faba bean flours. Food Research International 2019, 122, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyango, C.A.; Ochanda, S.O.; Mwasaru, M.A.; Ochieng, J.K.; Mathooko, F.M.; Kinyuru, J.N. Effects of malting and fermentation on anti-nutrient reduction and protein digestibility of red sorghum, white sorghum and pearl millet. Journal of Food Research 2013, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Waller, M.; Barrett, A.J.; Bateman, A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42, D503–D509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Barrett, A.J. Evolutionary families of peptidases. Biochemical Journal 1993, 290, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavidel, R.A.; Prakash, J.; Davoodi, M.G. Assessment of enzymatic changes in some legume seeds during germination. Agro FOOD Ind Hi Tech 2011, 22, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels, M.J.; Boulter, D. Control of storage protein metabolism in the cotyledons of germinating mung beans: role of endopeptidase. Plant Physiology 1975, 55, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, S.; Chen, Z. Plant protease inhibitors in therapeutics-focus on cancer therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2016, 7, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.D.; Volpicella, M.; Licciulli, F.; Liuni, S.; Gallerani, R.; Ceci, L.R. PLANT-PIs: a database for plant protease inhibitors and their genes. Nucleic acids research 2002, 30, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellinger, R.; Gruber, C.W. Peptide-based protease inhibitors from plants. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustgi, S.; Boex-Fontvieille, E.; Reinbothe, C.; von Wettstein, D.; Reinbothe, S. The complex world of plant protease inhibitors: Insights into a Kunitz-type cysteine protease inhibitor of Arabidopsis thaliana. Communicative & integrative biology 2018, 11, e1368599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.K.; Koundal, K.R. Plant protease inhibitors in control of phytophagous insects. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2002, 5, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.C.; Hwang, I.; Cheong, H.; Nah, J.W.; Hahm, K.S.; Park, Y. Protease inhibitors from plants with antimicrobial activity. International journal of molecular sciences 2009, 10, 2860–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, P.J.; Owusu-Apenten, R.; McCann, M.J.; Gill, C.I.; Rowland, I.R. Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and other plant-derived protease inhibitor concentrates inhibit breast and prostate cancer cell proliferation in vitro. Nutrition and cancer 2012, 64, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T. Plant food anti-nutritional factors and their reduction strategies: an overview. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2020, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccialupi, P.; Ceci, L.R.; Siciliano, R.A.; Pignone, D.; Clemente, A.; Sonnante, G. Bowman-Birk inhibitors in lentil: Heterologous expression, functional characterisation and anti-proliferative properties in human colon cancer cells. Food Chemistry 2010, 120, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, A.; Gee, J.M.; Johnson, I.T.; MacKenzie, D.A.; Domoney, C. Pea (Pisum sativum L.) Protease Inhibitors from the Bowman− Birk Class Influence the Growth of Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma HT29 Cells in Vitro. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2005, 53, 8979–8986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sehgal, S. Effect of domestic processing, cooking and germination on the trypsin inhibitor activity and tannin content of faba bean (Vicia faba). Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 1992, 42, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.; Diaz-Pollan, C.; Hedley, C.L.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Evolution of trypsin inhibitor activity during germination of lentils. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1995, 43, 2231–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, A. Metabolism of trypsin-inhibitory proteins in the germinating seeds of kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Planta 1972, 107, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S.; Liener, I.E. Effect of germination on trypsin inhibitor and hemagglutinating activities in Phaseolus vulgaris. Journal of Food Science 1988, 53, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.P. Anti-nutritional and toxic factors in food legumes: a review. Plant foods for human nutrition 1987, 37, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, D.C.; Sanctuary, M.R.; Qu, Y.; Khajavi, S.H.; Van Zandt, A.E.; Dyandra, M.; Frese, S.A.; Barile, D.; German, J.B. Personalizing protein nourishment. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2017, 57, 3313–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T.; Mosenthin, R.; Zimmermann, B.; Greiner, R.; Roth, S. Distribution of phytase activity, total phosphorus and phytate phosphorus in legume seeds, cereals and cereal by-products as influenced by harvest year and cultivar. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2007, 133, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liener, I.E. Implications of antinutritional components in soybean foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition 1994, 34, 31–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adawy, T.A. Nutritional composition and antinutritional factors of chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.) undergoing different cooking methods and germination. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2002, 57, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, R.S.; Bhartiya, A.; ArunKumar, R.; Kant, L.; Aditya, J.P.; Bisht, J.K. Impact of dehulling and germination on nutrients, antinutrients, and antioxidant properties in horsegram. Journal of food science and technology 2016, 53, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R.; Aguirre, A.; Marzo, F. Effects of extrusion and traditional processing methods on antinutrients and in vitro digestibility of protein and starch in faba and kidney beans. Food chemistry 2000, 68, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Das, M.; Dwivedi, P.D. A comprehensive review of legume allergy. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology 2013, 45, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.M.; Khan, F.; Luthria, D.L.; Garrett, W.; Natarajan, S. Proteomic analysis of anti-nutritional factors (ANF’s) in soybean seeds as affected by environmental and genetic factors. Food Chemistry 2017, 218, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, H.A.; O’Mahony, L.; Burks, A.W.; Plaut, M.; Lack, G.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of food allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2018, 141, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astwood, J.D.; Leach, J.N.; Fuchs, R.L. Stability of food allergens to digestion in vitro. Nature biotechnology 1996, 14, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troszyńska, A.; Szymkiewicz, A.; Wołejszo, A. The effects of germination on the sensory quality and immunoreactive properties of pea (Pisum sativum L.) and soybean (Glycine max). Journal of food quality 2007, 30, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Guan, R.X.; Liu, Z.X.; Li, R.Z.; Chang, R.Z.; Qiu, L.J. Synthesis and degradation of the major allergens in developing and germinating soybean seed. Journal of integrative plant biology 2012, 54, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, J.; Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Burlingame, B. Protein quality evaluation twenty years after the introduction of the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score method. British Journal of Nutrition 2012, 108(S2), S183–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilés-Gaxiola, S.; Chuck-Hernández, C.; del Refugio Rocha-Pizaña, M.; García-Lara, S.; López-Castillo, L.M.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Effect of thermal processing and reducing agents on trypsin inhibitor activity and functional properties of soybean and chickpea protein concentrates. Lwt 2018, 98, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Chakraborty, R.; Dutta, A. Role of fermentation in improving nutritional quality of soybean meal—a review. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2016, 29, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.J.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.W. Aspergillus oryzae GB-107 fermentation improves nutritional quality of food soybeans and feed soybean meals. Journal of medicinal food 2004, 7, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Frías, J.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Vidal-Valdeverde, C.; de Mejia, E.G. Immunoreactivity reduction of soybean meal by fermentation, effect on amino acid composition and antigenicity of commercial soy products. Food Chemistry 2008, 108, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Wan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, X.; Xie, M.; Li, X.; Fu, G. Research progress in peanut allergens and their allergenicity reduction. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 93, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketnawa, S.; Ogawa, Y. Evaluation of protein digestibility of fermented soybeans and changes in biochemical characteristics of digested fractions. Journal of Functional Foods 2019, 52, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojokoh, A.O.; Yimin, W. Effect of fermentation on chemical composition and nutritional quality of extruded and fermented soya products. International Journal of Food Engineering 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, A.M.; Yatsu, L.Y.; Ory, R.L.; Engleman, E.M. Seed proteins. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 1966, 17, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Gorbach, D.; Lukasheva, E.; Mavropolo-Stolyarenko, G.; Bilova, T.; Soboleva, A.; Tsarev, A.; Romanovskaya, E.; Podolskaya, E.; Zhukov, V.; et al. Bringing new methods to the seed proteomics platform: challenges and perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrokhi, N.; Whitelegge, J.P.; Brusslan, J.A. Plant peptides and peptidomics. Plant biotechnology journal 2008, 6, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessada, S.M.; Barreira, J.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Pulses and food security: Dietary protein, digestibility, bioactive and functional properties. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 93, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, S.; Platel, K.; Srinivasan, K. Influence of germination and fermentation on bioaccessibility of zinc and iron from food grains. European journal of clinical nutrition 2007, 61, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sprout species | Pre-germination | Post-Germination | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea Chickpea desi Chickpea desi |

24.4% 18.4% 32±1.8%* 22.3% ~20% 20.3% 14.8 ± 0.6% ~21% |

27.7% 24.6% 48±0.5%* 24.1% 23.9% 23.6% 15.9 ± 0.4% 24.1% |

Xu et al (2019) [25] Ferreira et al (2019) [26] Dipnaik and Bathere (2017) [27] Mansour (1987) [28] Khalil et al (2007) [29] Uppal et al (2012) [11] Kumar et al (2019) [30] Khalil et al (2007) [29] |

| Mungbean | 22.5±0.9% 22.3% |

36±0.5% 24.9% |

Dipnaik and Bathere (2017) [27] Uppal et al (2012) [11] |

| Cowpea | 30±1.07% 22.5% |

40±0.5% 24.9% |

Dipnaik and Bathere (2017) [27] Uppal et al (2012) [11] |

| Moth bean | 30±1.0% | 40±12.3% | Dipnaik and Bathere (2017) [27] |

| Soybean | 40.2±0.3% 39.1% |

46.3±0.4% 45.1% |

Joshi and Varma (2016) [31] Kayembe et al (2013) [32] |

| Faba bean | 26.4% | 30.6% | Kassegn et al (2018) [33] |

| Pea var ucero var ramrod var agra |

25.4± 0.1% 21.1 ± 0.0% 22.9 ± 0.1% |

27.0 ± 0.1% 22.7 ± 0.1% 22.7 ± 0.1% |

Martinez-Villaluenga et al (2008) [34] Martınez-Villaluenga et al(2008)[34] Martınez-Villaluenga et al (2008)[34] |

| Black gram | 20±1.5% | 36±1.54=% | Dipnaik and Bathere (2017) [27] |

| Broccoli | 26.1% | 29.8% | Taraseviciene et al (2009) [35] |

| Brown Rice | 6.9 ± 0.0% | 8.9 ± 0.2% | Moongngarm et al (2010) [36] |

| Sprout species | Pre- germination |

Post- Germination |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea (major globulin) | 45.85% | 37.08% | Portari et al (2005)[44] |

| Pea (albumin + globulin) var ucero var ramrod var agra |

28.95% 26.71% 26.67% |

24.9% 22.69% 25.03% |

Martinez-Villaluenga et al (2008)[34] |

| Lupin | 12.81% | 15.7% | Villacrés et al (2015)[45] |

| Sweet lupin (albumin + globulin) Lupinus luteus cv. 4486 Lupinus luteus cv. 4492 Lupinus angustifolius cv.troll Lupinus angustifolius cv.zapato |

36.89% 39.63% 34.9% 35.4% |

39.45% 35.91% 35.2% 29.48% |

Gulewicz et al (2008)[46] |

| Sorghum | 25% | 28% | Afify et al (2012)[47] |

| Free amino acids | Pre- germination |

Post- germination |

all amino acids |

Pre- germination |

Post- germination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arg | 0.1 | 0.94 | Arg | 10.61 | 12.11 |

| His | 0.22 | 0.68 | His | 8.74 | 10.79 |

| Ile | 0 | 2.06 | Ile | 6.26 | 11.44 |

| Leu | 0 | 2.05 | Leu | 10.64 | 17.1 |

| Lys | 0 | 0.93 | Lys | 4.54 | 16.99 |

| Met | 0 | 0.26 | Met | 1.49 | 1.02 |

| Cys | 0 | 0 | Cys | 0.4 | 0 |

| Phe | 0 | 2.32 | Phe | 6.7 | 11.56 |

| Tyr | 0 | 1.1 | Tyr | 6.34 | 7.7 |

| Pro | 0.17 | 3.24 | Pro | 11.11 | 10.84 |

| Ser | 0 | 2.64 | Ser | 11.38 | 15.54 |

| Thr | 0.03 | 1.18 | Thr | 5.57 | 7.14 |

| Val | 0 | 2.83 | Val | 8.54 | 13.23 |

| Trp | 0 | 0.52 | Trp | 0 | 0 |

| Ala | 0.45 | 3.21 | Ala | 20.42 | 36.76 |

| Asp | 0.18 | 0.32 | ASX* | 10.96 | 41.39 |

| Asn | 0.51 | 18.96 | |||

| Glu | 0.48 | 3.15 | GLX* | 26.55 | 34.12 |

| Gln | 0 | 1 | |||

| Gly | 0.05 | 1.23 | Gly | 9.77 | 10.77 |

| Total | 2.19 | 48.62 | 160.02 | 258.50 |

| Amino acids | Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) | Lentils (Lens culinaris) | Pea (Pisum sativum) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germination | Pre- | Post- | Pre- | Post- | Pre- | Post- |

| Alanine | 2.93 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.25 | 2.58 |

| Arginine | 13.2 | 2.95 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| Asparagine | 5.9 | 8.0 | 0.88 | 28.7 | 0.8 | 23.0 |

| Aspartic acid | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.70 | 1.27 | 1.6 | 5.4 |

| Glutamic acid | 11.2 | 4.09 | 1.34 | 3.93 | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| Glutamine | 0.0 | 1.27 | 0.0 | 1.06 | 0.0 | 2.38 |

| Glycine | 0.50 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.30 |

| Histidine | 0.45 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.0 |

| Isoleucine | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.99 | 0.0 | 0.58 |

| Leucine | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| Lysine | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.0 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| Methionine | 0.0 | 0.382 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Phenylalanine | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.04 | 0.15 | 1.16 |

| Proline | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.23 | 2.91 | 0.53 | 2.23 |

| Serine | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.43 | 0.02 | 1.51 |

| Threonine | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.042 | 2.12 | 0.0 | 0.36 |

| Tryptophan | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.0 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| Tyrosine | 4.0 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.52 |

| Valine | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.11 | 2.42 | 0.0 | 1.78 |

| Total | 48.47 | 33.27 | 4.52 | 52.59 | 9.2 | 50.86 |

| Sprout species | Pre-germination | Post-Germination | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea | 67.7% 75.4% 64.2±1.8 |

79.0% 86.5% 73.4±0.7 |

Uppal et al (2012)[11] Chitra et al (1996)[54] Ghavidel et al (2007)[55] |

| Mungbean | 66.4% 70.9% |

83.0% 82.7% |

Uppal et al (2012)[11] Chitra et al (1996)[54] |

| Cowpea | 73.3% 71.2 ± 0.1% |

85.7% 73.5±0.4 % |

Uppal et al (2012)[11] Kalpanadevi et al (2013)[56] |

| Soybean | 63.3% | 73.6% | Chitra et al (1996)[54] |

| Pigeon Pea | 69.1% | 85.1% | Chitra et al (1996)[54] |

| Kidney bean | 80.6 ± 0.02% | 87.1 ± 0.03% | Shimelis et al (2006)[57] |

| Yellow pea | 78.6 ± 0.1% | 79.9 ± 0.1% | Setia et al (2019)[58] |

| Faba bean | 78.0 ± 0.2% | 80.4 ± 0.1% | Setia et al (2019)[58] |

| Lentil | 65.6±1.1% | 64.2±1.8% | Ghavidel et al (2007)[55] |

| Green gram | 61.0±1.0% | 72.7±0.8% | Ghavidel et al (2007)[55] |

| Sorghum | 51% | 65% | Afify et al (2012)[47] |

| Red sorghum | 48% | 68.1% | Onyango et al (2013)[59] |

| Pearl Millet | 21.5% | 34.5% | Onyango et al (2013)[59] |

| Sprout species | Pre-germination | Post-Germination | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea |

11.9 |

7.86 |

El-Adawy (2002)[82] |

| Mungbean | 16.5 | 12.8 | El-Adawy et al (2003)[82] |

| Pea | 10.8 | 8.6 | El-Adawy et al (2003) [82] |

| Lentil | 33.3 | 27.3 | El-Adawy et al (2003) [82] |

| Horsegram | 11.5 | 8.4 | Pal et al (2013)[83] |

| Kidney bean Roba variety Awash variety Beshbesh variety |

4.5 20.8 29.2 |

3.8 17.3 24.5 |

Shimelis et al [75] |

| French bean | 3.1 | 2.2 | Alonso et al (1999)[84] |

| Faba bean | 4.4 | 3.3 | Alonso et al (1999)[84] |

| Sorghum Hamra variety |

31.6 |

19.9 |

Osman et al (2013)[78] |

| Allergic protein family | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Prolamin superfamily | Largest family of plant food allergens Low molecular weight Sulphur rich Glycosylated Includes 2S storage proteins from legumes, non-specific lipid transfer proteins, protease inhibitors |

| Cupin superfamily | Consists of 2 conserved consensus sequence motifs β barrel structural domain Seed storage proteins of soybeans and peanuts |

| Pathogenesis-related proteins | Comprised of 14 different unrelated protein families. Small size Stable in acidic conditions Increased synthesis during environmental and pathogen stresses |

| Profilins | Small 12-15 kDa MW Highly conserved sequences Cytoplasmic Immunological cross-reactivity with pollens |

| Vicilins | Part of globulin family Anti-fungal, anti-microbial activity |

| Glycilins | Hexamer 300–400 kDa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).