Introduction

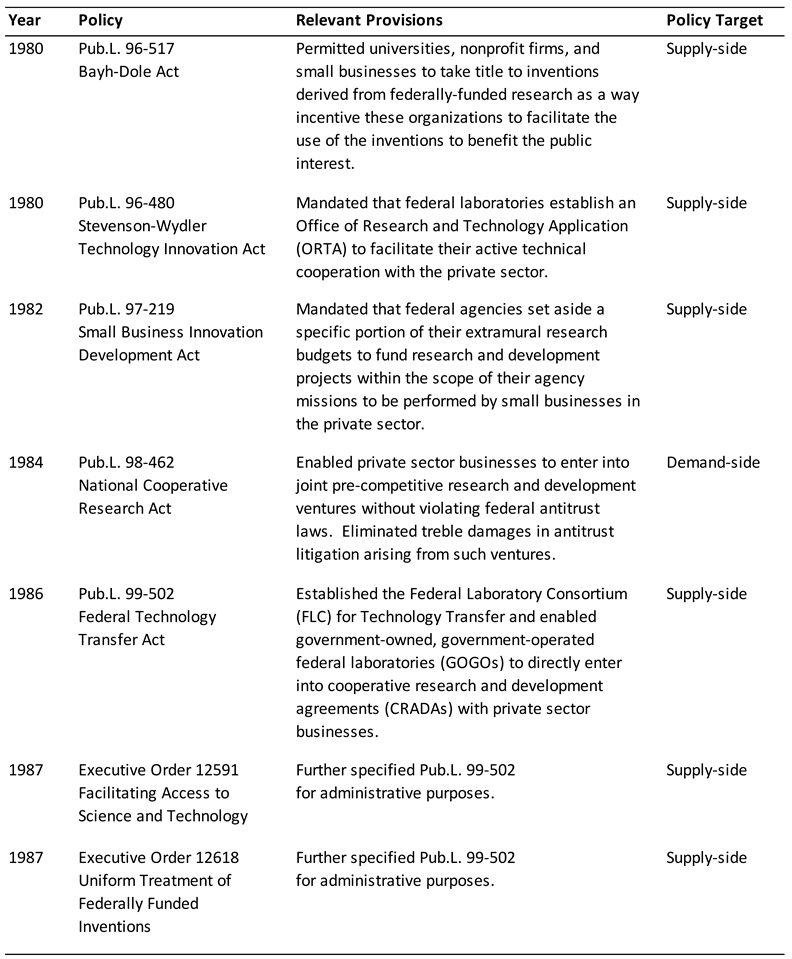

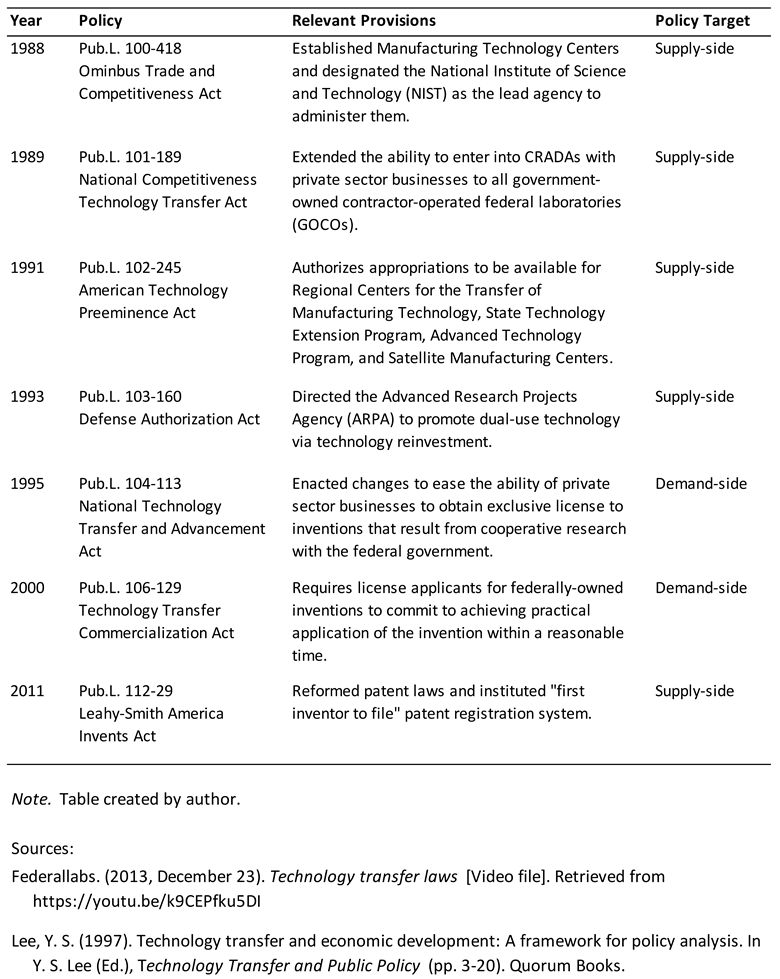

The transfer of technologies created at universities and federal laboratories to the private sector for use that benefits the public interest (i.e., technology transfer) has been an important public policy concern of the federal government since the end of the Second World War. To date, the U.S. Congress has enacted at least 14 major pieces of legislation regarding technology transfer (see

Table 1). Additional major legislation has also been proposed or is contemplated. Much if not most of this legislation is regulatory in nature and targeted toward universities and federal laboratories as creators of technologies (i.e., supply-side actors). These facts clearly illustrate that the federal government has taken and will continue to pursue significant intervention in technology transfer.

The underlying assumption of the discourse about technology transfer is that government intervention is legitimate. Little scholarship has examined whether this assumption is valid or not and on what basis. Just because government action regarding technology transfer is constitutionally valid and within the bounds of legality does not mean that constituents perceive it as a legitimate use of government power and resources.

Considering the legitimacy of government intervention in technology transfer is important for several reasons. It serves to define the boundary for the kinds of problems with which the government should concern itself and provides guidance about the actions that policymakers can justifiably consider for resolving those problems. Moreover, providing a sound conceptual anchoring for the legitimacy of technology transfer policy should help to prevent scholarly research from fragmenting into a cacophony of unhelpful noise masking the signals of useful insights.

This paper examines the basis for claims of legitimacy for government intervention in technology transfer. It aims to answer four primary questions. First, on what basis can policymakers claim that government intervention in technology transfer is a legitimate use of the power and authority of government? Second, what are the limits concerning the kinds of technology transfer problems that the government can claim are its legitimate concerns? Third, what are the limits to the kinds of solutions to those technology transfer problems that policymakers can claim are legitimate options? And finally, what are the likely consequences if policymakers take actions in the field of technology transfer that a significant majority of constituents consider illegitimate uses of the power and authority of the government?

To answer these questions, this paper examines, assimilates, and combines concepts and theories from economics, organization studies, and political philosophy. This exposition adds to the knowledge base about technology transfer by identifying concepts and constructs from these fields and defining their relationship to the phenomenon of government intervention in technology transfer. The examination aims to develop logical and complete arguments about the relationships among relevant key concepts and constructs in the context of technology transfer. It explains how such constructs are linked as well as the theoretical explanation for those links.

Background

Legitimacy is an important construct in the context of public policy. It is the idea that the governed must accept the right of the governing authority to act and the appropriateness of such actions. Legitimacy is thought to be a necessary condition for a functional government over the long term. Government intervention through regulation, taxation, and redistribution can only be sustained if the public views such action as legitimate.

The creation and transfer of technologies to the private sector is an area where there is significant government intervention. Research and development activity is the primary source of technological development. Currently, the government of the United States of America (U.S.) outlays more than $150 billion each year for research and development with nearly $40 billion of that being directed to universities and colleges (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2022). The government can only continue with such policies so long as Americans accept such action as a legitimate use of the power and authority they have conferred to the federal government and their elected officials.

A review of the literature revealed little discourse examining the legitimacy of technology policy at the macro level. The literature discusses legitimacy as it relates to technology policy primarily at the micro level. Studies generally focus on legitimacy as a necessary condition for a government to justify spending public money on specific kinds of technology development projects and ways to assess it (see e.g., Bergek, Jacobsson, & Sandén, 2008; Blankesteijn & Bossink, 2020; Pace, Pearson, & Lipworth, 2017). Macro-level and meso-level perspectives on the legitimacy of technology policy appear to be missing in the literature, particularly as it relates to government intervention to encourage and facilitate the transfer of technology from federal laboratories and universities to the private sector.

Wijnberg (1994) is one of the few works that undertake such a macro-level examination of the legitimacy of technology policy. This was done as a basis for establishing legitimacy claims for public support of the arts. The examination is firmly rooted in neoclassical economic theory regarding market failures and merit goods. However, the examination of the basis of legitimacy claims for technology policy focused on the creation of technology through publicly supported research and development. It did not extend to the transfer of such technologies for use in the private sector.

There are those who would simply brush aside the question of the political legitimacy of government intervention in the stimulation of technological development and its application in the private sector. Branscom (1992) argued that “…the issue isn’t whether the United States should have a technology policy – it already does – but what kind of government policies and programs make sense in the new competitive environment.“ This is indicative of the mentality of those who would take the legitimacy of government intervention in technology transfer as

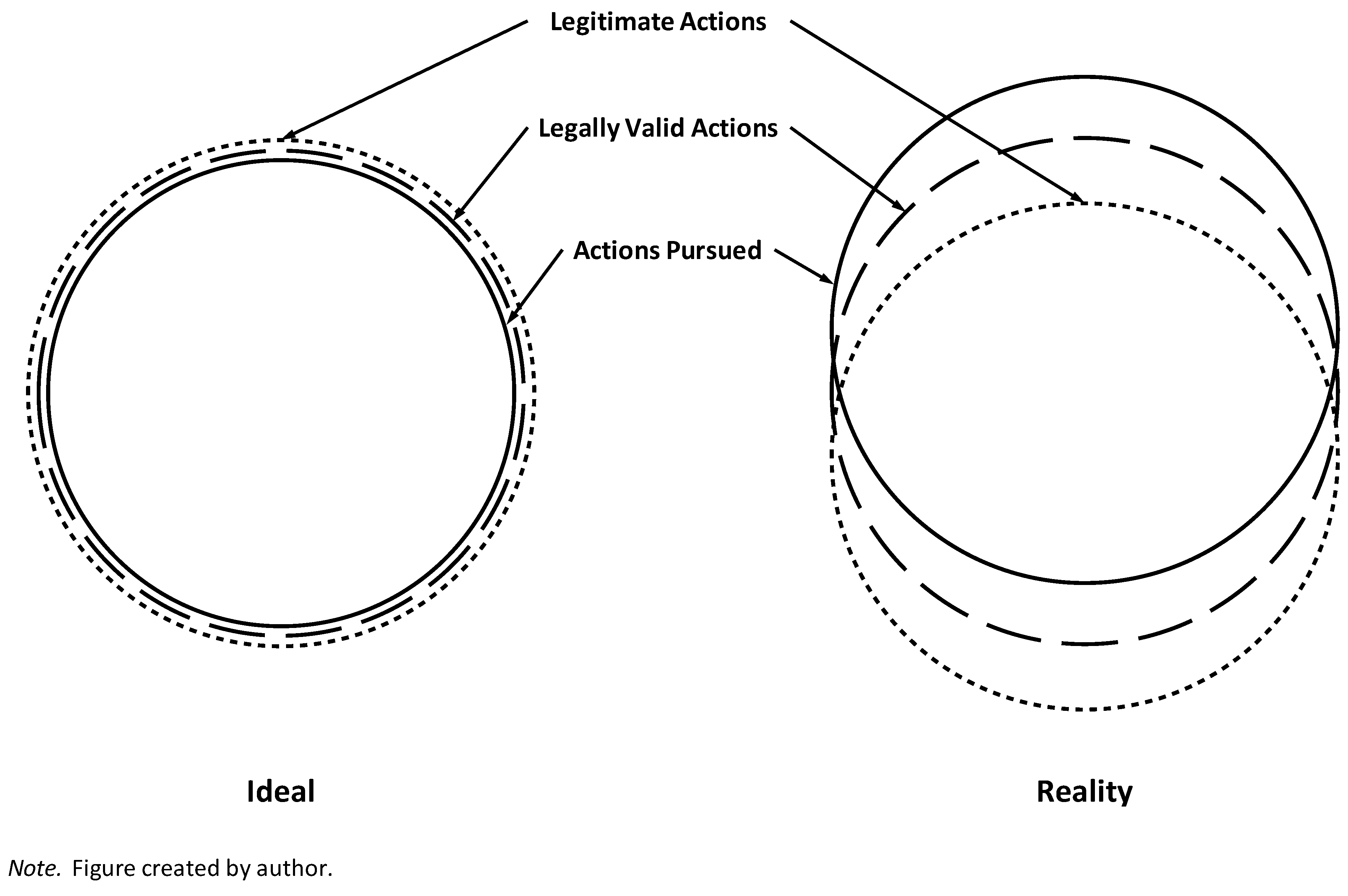

fait accompli without the need for further consideration. However, this is shortsighted. The legitimacy of the government to act is not established simply because it has acted. In a perfect world, politically legitimate actions, legally valid actions, and pursued policies would align but this is not always the case (see

Figure 1). Moreover, establishing legitimacy is not a one-time event. Legitimacy must be regularly reaffirmed because the public is often fickle, its memory tends to be short, and the environment in which the government implements public policy is continually changing.

Defining the Conceptual Domain.

The previous section situated the topic within the discourse of legitimacy and technology transfer policy. This section of the paper briefly describes the framework that will be used to analyze the substantive issues of legitimacy in the context of technology transfer. It begins by considering theories, concepts, and constructs relevant to the domain of interest. These elements are analogous to the data in an empirical study. It then explains the theoretical framing that will be used to generate insights. This is analogous to the methods elements of an empirical study. This analytical framework is used to apply alternative contexts and propose a new take on extant conceptualizations of the political legitimacy of technology transfer policy.

Theories, Concepts, and Constructs of Legitimacy

There are a variety of theories, constructs, and concepts that come into play when examining the legitimacy claims of government intervention in technology transfer. Technology and technology transfer are two of the primary constructs that must be clearly defined. Although the term technology is used regularly in both scholarly and public discourse, its meaning is not precise. For the purposes of this examination, technology is defined as culturally influenced information that social actors use to pursue the objectives of their motivations, and which is embodied in such a manner as to enable, hinder, or otherwise control its access and use. The author presented and justified this definition in his dissertation titled The Influence of Technology Maturity Level on the Incidence of University Technology Transfer and the Implications for Public Policy and Practice. Technology transfer is thus defined as the conveyance of technology (as defined above) from the possession of one social actor (i.e., universities and federal laboratories) to the possession of another social actor (i.e., private sector organizations) for the purpose of applying the technology in a setting in which it has not previously been applied (see Footnote 2).

The concept of political legitimacy has been debated for millennia. But because of disciplinary specialization, the term has come to mean different things to philosophers, social scientists, and lawyers (Greene, 2019). Trover (2011) defined legitimacy as “a state of appropriateness ascribed to an actor, object, system, structure, process, or action resulting from its integrations with institutional norms, values, and beliefs.” This definition suggests that in some respects, legitimacy is a reflection of values and preferences. Suchman (1995) defined legitimacy in an organization studies context as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.” This definition is broad-based and is quite applicable to government institutions and their actions. More recently, Greene proposed conceptualizing legitimacy as a system-level property produced when the subjects of a political order assent to being ruled. By this definition, political legitimacy is a social-political good produced by a society members’ assent, but not all assent to rule contributes to legitimacy (Greene).

If people consider a government action to be legitimate, then they will accept the action and abide by its requirements even if the action is not what they would have preferred or considered the best course of action in the given circumstances. For any government policy to be effective and long-enduring, a significant majority of the population must deem it legitimate. Otherwise, efforts to undermine or overturn the political order by those who do not consider the policy to be legitimate will gain traction, cause political strife, and destabilize the social order. However, it should be noted that considering a policy ineffective, undesirable, or even harmful is not the same as considering it illegitimate.

Legitimacy denotes the reaction of a collectivity to the pattern of behavior of an organization as observed by them (Suchman, 1995). When legitimacy exists, a group of interested people accepts, as a whole, what they perceive to be the behavioral pattern of the organization, as a whole, despite the reservations that any single person may have about a single behavior or isolated action of the organization or their knowledge of concerns that other persons might have about such behavior or action (Suchman). This seems quite applicable to government institutions as well.

The legitimacy typology that Weber (1922/1958) described is probably among the most well-known frameworks. It describes three types of political legitimacy termed legal-rational, traditional, and charismatic. More recently, Lenowitz (2019) argued that there are at least three types of political legitimacy namely moral legitimacy, legal legitimacy, and sociological legitimacy. However, scholars have proposed other frameworks and conceptions of legitimacy that might prove more useful for our purposes.

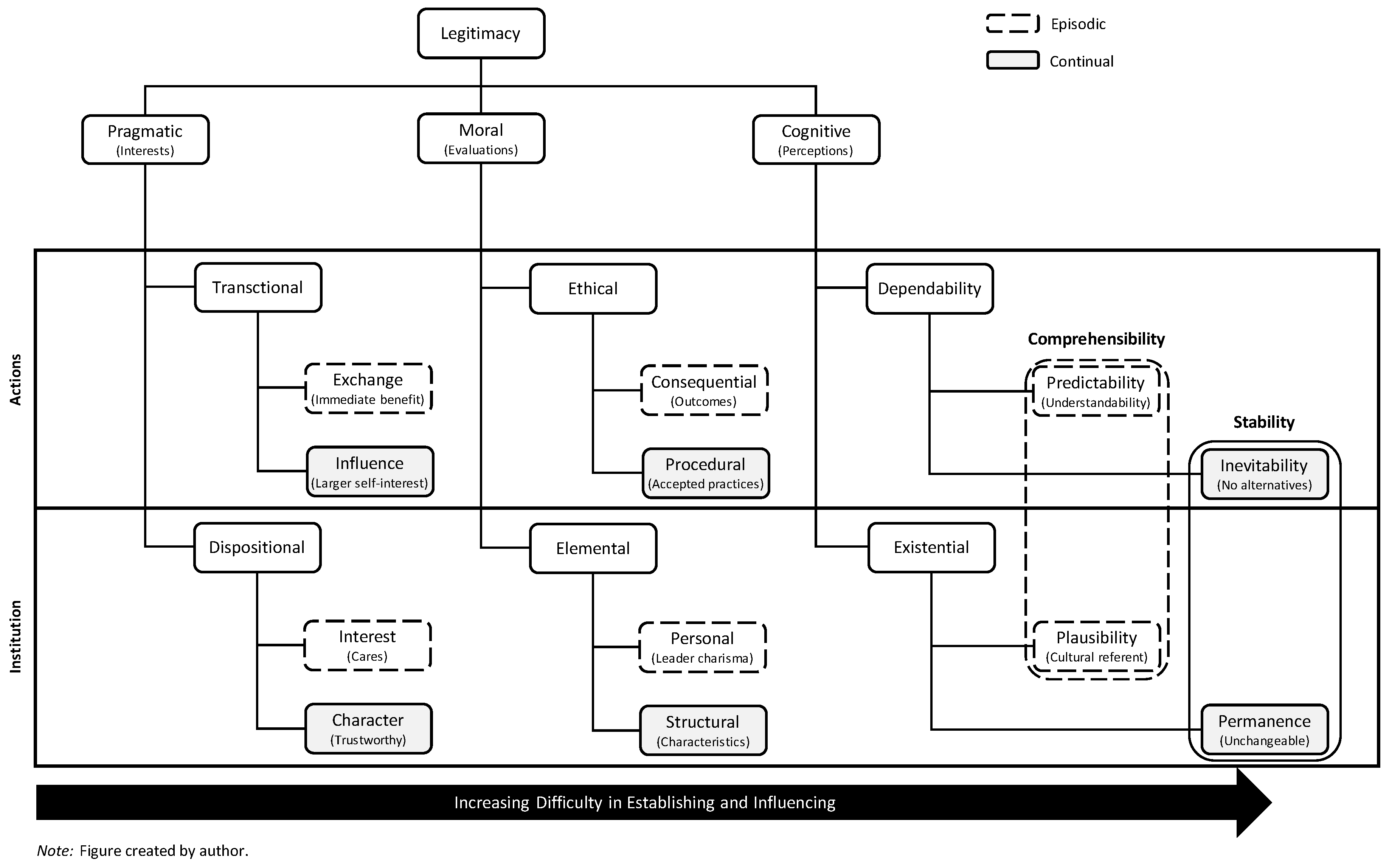

In the fields of organization studies and management studies, scholars have developed legitimacy theory to explain what constrains and enables organizational actors within a given society. Suchman (1995) described a typology of three primary kinds of organizational legitimacy that can be applied in the context of public policy (see

Figure 2). Termed

pragmatic legitimacy, moral legitimacy, and

cognitive legitimacy, these types of legitimacy are produced by different behavioral dynamics and comprise various subtypes (Suchman). Pragmatic legitimacy is essentially a kind of reciprocity in which a particular set of constituents bases its decision about the appropriateness of a policy on its expected impact on them (Suchman). Pragmatic legitimacy is instrumental in nature. With moral legitimacy, constituents base their decisions about the appropriateness of a policy on judgments about whether it is the right thing to do according to some normative belief (Suchman). Moral legitimacy is normative in nature and driven by ideology. The various subtypes of moral legitimacy roughly parallel the typological framework that Weber (1922/1958) described (Suchman). Finally, cognitive legitimacy is based on constituents’ perceptions about the organization and its actions relative to some cultural benchmark (Suchman). As such, cognitive legitimacy is very much psychological and sociological in nature. Except for dispositional legitimacy, Suchman did not label the first-level subtypes of legitimacy, which I have done in

Figure 1 to aid understanding.

The typology of legitimacy that Suchman (1995) described is not strictly hierarchical. But as one moves from pragmatic to moral to cognitive, legitimacy is generally expected to be more difficult to establish and influence (Suchman). It is also expected to generally become harder to notice, more visceral, and more self-reaffirming (Suchman).

Neoclassical economic theory has long been the basis for how many scholars and policymakers make claims of legitimacy for government policy. It specifies that government intervention is always legitimate in cases of market failure resulting in markets that are less than Pareto efficient (Stiglitz, 2000; Wijnberg, 1994). According to neoclassical economic theory, there are six conditions that produce markets that are not Pareto efficient – public goods, negative externalities, failure of competition, incomplete markets, information failures, and macroeconomic disequilibria (Stiglitz).

There are also conditions outside of market failures that neoclassical economic theory considers to be reasonable grounds for government intervention. One is an undesirable distribution of income, and the other is the case of merit goods (Stiglitz, 2000). The criterion of Pareto efficiency does not consider the distribution of income throughout a society (Stiglitz). It is quite possible for markets and economies that are Pareto efficient to leave many people without the resources to achieve a minimally acceptable standard of living according to the values and mores of society. Such circumstances are counter to the generally accepted norms of the population. Moreover, they can lead to social strife. In the case of merit goods, the government forces consumption because, in the absence of such action, individuals will fail to consume goods and services that benefit them (Stiglitz). This kind of government intervention can be warranted. There is no guarantee that people’s perceptions of their own welfare will be accurate and reliable for making judgments about actions that affect their welfare, even when fully informed (Stiglitz). Under such circumstances, people’s failure to consume goods and services beneficial to their welfare could also impose negative externalities on society.

Dynamic theory (sometimes called Schumpeterian theory or evolutionary theory) is another framework that could be applied to evaluate the legitimacy claims of government actions. Advocates of dynamic theory argue that the conditions for a perfect market under neoclassical economic theory are unrealistic (Wijnberg, 1994). Therefore, using the perfect market ideal type as a yardstick for determining the appropriateness of government action is fundamentally flawed. Under dynamic theory, a properly functioning market is one that enables the maximum amount of innovation and change and thus is a market in a state of continuous disequilibrium (Wijnberg).

Another concept that seems relevant to evaluating legitimacy claims of government action is the categorical imperative that Kant (1785/2018) introduced. A categorical imperative is an absolute and unqualified requirement that is to be followed in all scenarios and constitutes an end in itself. According to Kant’s first formulation of the categorical imperative, people should only take actions that they would consent to (and in fact want) the underlying principle to become a universal law. In this respect, only actions that satisfy the categorical imperative criteria are legitimate.

Meta-Level Conceptual Framework

The examination of the basis of legitimacy claims for government intervention in technology transfer is aided by the lenses of social constructionism and Reich’s (1987) typology of morality tales. Social constructionism provides a framework for understanding legitimacy as a social phenomenon, which is not a concrete phenomenon like universal physical constants that exist outside of human social interaction. Reich’s typology of morality tales enables us to consider how ideology and worldview influence political considerations such as the legitimacy of government actions.

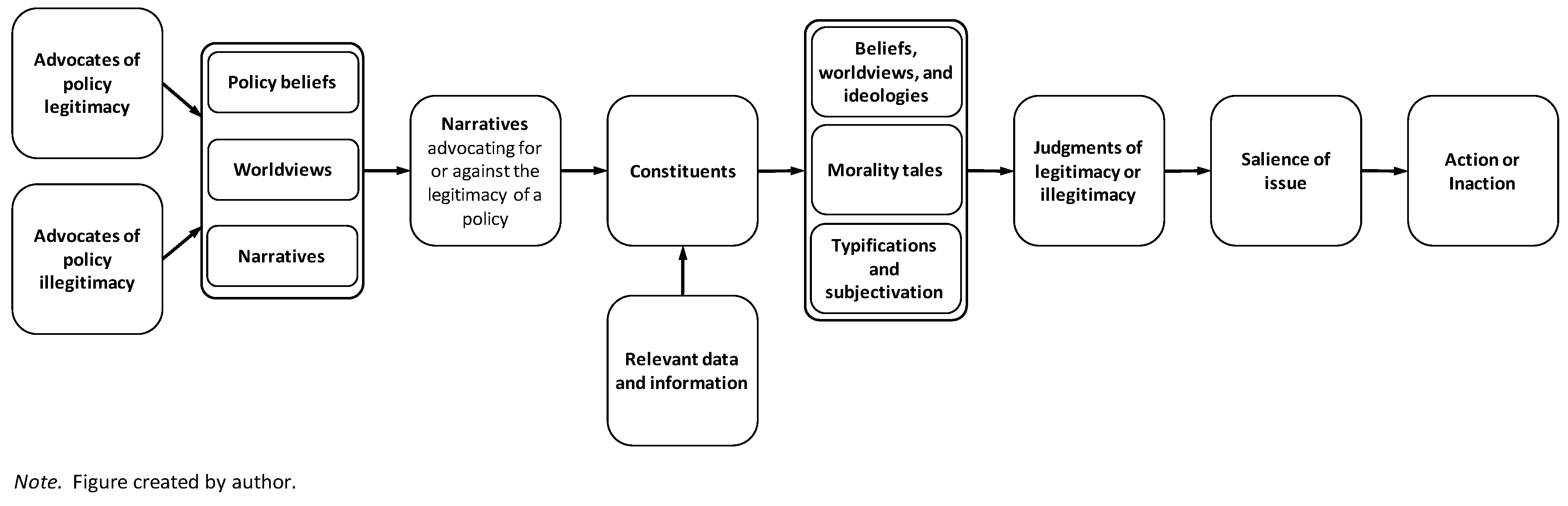

Political legitimacy is a human construct and not a phenomenon of nature. When studying it, one must be cautious about reifying the construct. Judgments about legitimacy are based on the meaning that people attribute to the actions of institutions. Fundamental to social constructionism is the idea that people develop meaning about social phenomena primarily through interactive communication with others and not individually (Littlejohn & Foss, 2009). Moreover, social phenomena do not have meaning independent of the historically informed mental and linguistic representations that people ascribe to them (Berger & Luckmann, 1991).

The question of how constituents come to judge government intervention as legitimate or illegitimate is essentially a question of how people apply everyday knowledge to attribute meaning to institutions and their actions. One cannot exist as a fully formed human being without regular interaction and communication with other people through various mechanisms that can be physically or temporally close together or removed (Berger & Luckman, 1966/1991). Much of this communication employs narratives, which people use to cognitively organize new information, and plays an important role in establishing reasoning for individual actions (Jones, McBeth, & Shanahan, 2014). There is an ongoing correspondence between one’s own meanings of the world and the meanings of others (Berger & Luckman). One’s own thinking is invariably influenced by this interaction.

Empirical research demonstrates that people use two distinct modes of thinking when forming judgments and making decisions (Kahneman, 2011). One mode is intuitive and emotionally driven while the other is analytical and intentional. Human decision-making is largely driven by the first thinking mode and the latter mode is often only triggered when the first fails to readily produce a solution (Kahneman). However, the analytical thinking mode defaults to a positive test strategy and tends to be uncritical (Kahneman) and thus does not offer complete inoculation against the vulnerabilities of the intuitive thinking mode. Additionally, people evaluate their options relative to a reference point rather than on an absolute basis when making decisions and formulating judgments (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Kahneman & Tversky, 2013; Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). When making judgments about the political legitimacy of government actions, such as technology transfer policy, people likely employ morality tales as their referent.

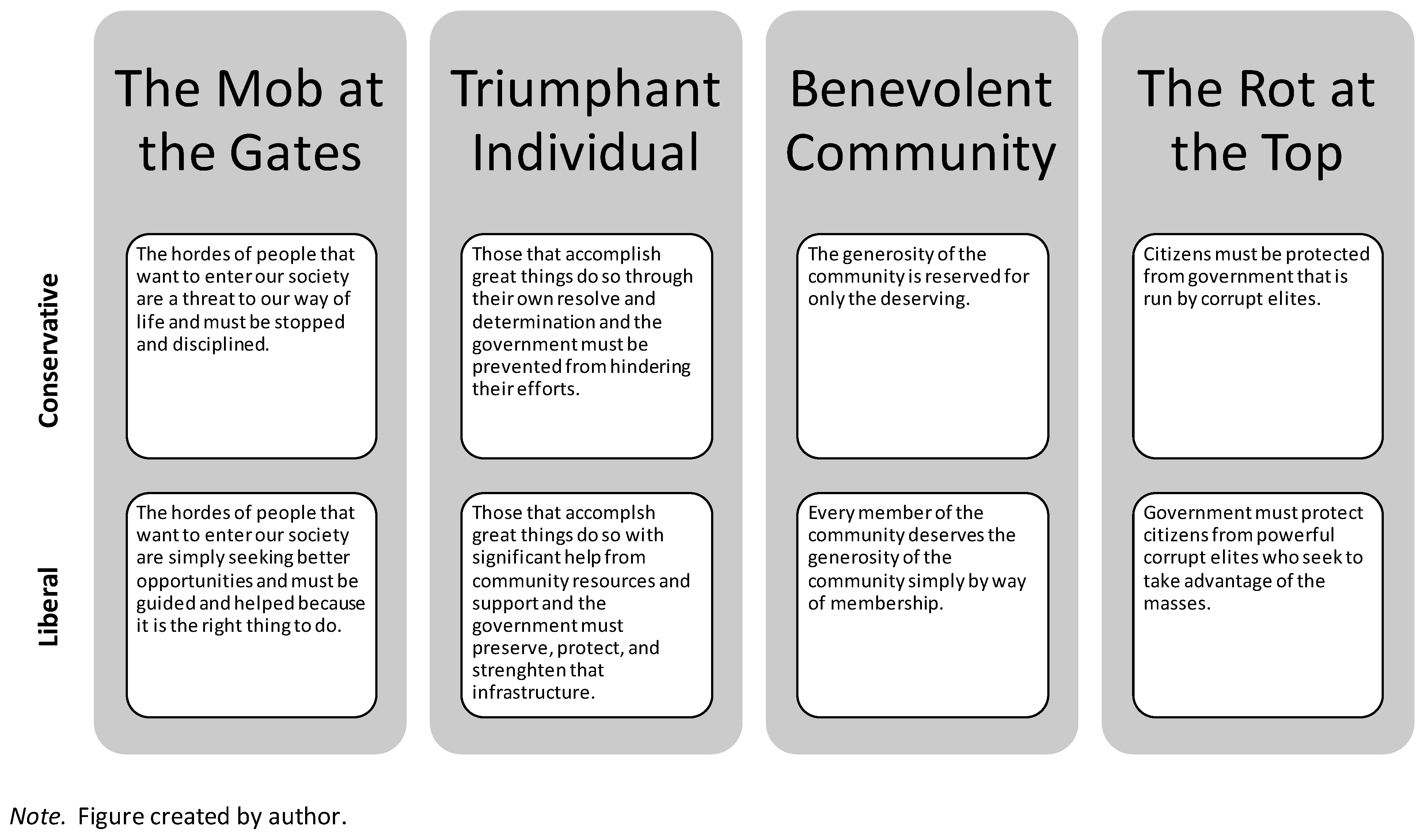

The morality tale is how people understand themselves, their society, and what they desire for themselves and their community. It helps people interpret and explain reality and informs what people come to expect of their fellow citizens and government (Reich, 1987). Reich’s typology comprises four basic morality tales, each with a liberal and a conservative variant (see

Figure 3). However, regardless of the specific variation that captures each person’s ideology, the basic theme of all the American morality tales according to Reich is that America is:

“a nation of humble, immigrant origins, built out of nothing and into greatness through hard work; generous to those in need, those who cannot make it on their own; a loner among nations, suspicious of foreign entanglements, but willing to stand up against tyranny; and forever vigilant against corruption and special privilege.” (pp. 4-5).

Through the process of social constructionism and the lens of the morality tale, people make judgments about the political legitimacy of technology transfer policy and other government actions (see

Figure 4).

The discussion that follows in the next section attempts to revise and expound upon extant knowledge by modifying the perspective used to understand claims of legitimacy for technology transfer policy. The examination begins by problematizing the current relevant theories and concepts. While doing so, it expands upon the need for a reconfiguration or shift of perspective to better align the relevant theories and concepts to the issue at hand. It then attempts to integrate disparate concepts into a more conceptually robust framework to understand and explain the claims of legitimacy for government intervention in technology transfer.

The Legitimacy of Technology Transfer Policy

In the United States, it is a deeply ingrained principle that only the people as a whole can bestow legitimacy on power and authority. In Federalist Paper No. 49, James Madison argued that the people are the only legitimate source of power; it is the will of the people that bestows the government with the power to intervene in the activities of society (Hamilton, Jay, & Madison, 1788/1998). One can argue that the only legitimate use of government power is action intended to realize the will of the people. However, discerning the will of the people as a collectivity is not so straightforward, as Arrow’s impossibility theorem demonstrates. This is especially true in areas that are not highly visible or top-of-mind topics for citizens, such as technology transfer.

The Traditional View

Public sector economics has traditionally provided the basis for claims of legitimacy for the government’s interest in intervening in technology transfer. The justification for this intervention is rooted in the conception of technology and technology transfer as impure public goods and merit goods. In many respects, technology can be viewed as an impure public good whose consumption is non-rivalrous but excludable. The information and knowledge aspects of technology have public good characteristics (Lall, 2001). Technology, as defined for the purposes of this examination, is non-rivalrous given that use by one party does not diminish the stock for others. Once a technology is developed, its use by one person generally does not impede its use by another. However, technology may be made excludable by the nature of its embodiment or by conferring property rights in the form of intellectual property (i.e., patents, copyrights, and trade secrets) that can be enforced using the coercive powers of the state.

Generally speaking, technology transfer can also be thought of as an impure public good as well as a merit good. The marginal cost of an additional actor using a given technology is often negligible. Thus, technology transfer can be considered non-rivalrous. However, technology transfer can be made excludable through legal mechanisms such as options and licenses for intellectual property. A merit good satisfies a public want and could be provided by the market because it can be made excludable but is under-consumed simply because of consumer choice, not necessarily because of market failure (Desmarais-Tremblay, 2017; Musgrave, 1959). Moreover, its consumption produces positive externalities that far outweigh any negative externalities that such consumption might generate (Desmarais-Tremblay; Musgrave). As such, the government intervenes to force public consumption through the modification of individual choices rather than to mitigate a market failure (Desmarais-Tremblay; Musgrave). Technology transfer seems to satisfy the definition of merit goods. It produces societal, ecological, and economic benefits (Lidecap, 2009; Link & Scott, 2019). These benefits appear to far outweigh any negative consequences. Consequently, the nation’s elected leaders have decided that more technology transfer is needed than what is ordinarily produced as is evident by the implementation of public policy to encourage and facilitate it.

Technology transfer is also important because of the link between national economic prosperity and technological innovation. Solow (1957) estimated that roughly 88 percent of the total increase in real Gross National Product (GNP) is attributable to technological progress. Other researchers have drawn similar conclusions about the importance of technological change as a driver of economic growth (see e.g., Broughel & Thierer, 2019; Carlaw & Lipsey, 2003; Rosenberg, 2020). Consequently, technological progress is important for the nation to continue the way of life that citizens and residents of the country have come to expect. It is logical to conclude that technology transfer plays an important role in achieving this objective.

The United States currently faces several economic challenges. Poverty and impeded economic mobility continue to plague the nation (see e.g., Desmond & Western, 2018; Iceland, 2013; Rank, Eppard, & Bullock, 2021). Income inequality continues to rise and poses the risk of sparking political strife and social unrest (see e.g., Chambers, Swan, & Heesacker, 2014; Ryscavage, 2015; Novaro, de Lima Amaral, Huang, & Price, 2016). Given that technological progress is a major driver of economic growth, it is reasonable to assume that technology transfer will be a critical component of any major economic development policy that seeks to address these problems in a significant and long-enduring manner. In light of these linkages, increasing the incidence of technology transfer, regardless of the current incidence rate, is a reasonable public policy goal.

From a more pragmatic standpoint, the efficient use of scarce national resources makes technology transfer policy both important and necessary. Although the $163.73 billion in total R&D spending represented just roughly 2.4 percent of the federal government’s $6.8 trillion in total federal outlays in federal fiscal year 2021 (American Association for the Advancement of Science [AAAS], 2022; Congressional Budget Office, 2022), it is not a triviality considering that the amount is greater than the gross domestic product (GDP) of at least 160 countries (United Nations, 2021). Thus, government intervention to promote the use of technologies derived from federally funded research seems justified.

Schrier (1964) pointed out that there was a large stock of unexploited technology derived from federally funded research and development. The situation is largely unchanged to this day. There are other important problems of national interest to which the government could direct monies currently being spent on research and development such as road repairs, alleviating hunger, and addressing issues with inequity in the court system. Historically, federal research and development expenditures have exceeded federal spending on transportation, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and law courts each (Chantrill, 2023). It makes little sense to direct so many resources to the creation of technologies if those technologies will not be used to improve the economic and social well-being of people. In such a context, implementing policy to increase the use of technology derived from federally funded research and development seems appropriate.

Concerns and Challenges

There are several concerns and challenges to the traditional view of the legitimacy of technology transfer policy. They impede theory development and hamper the practical application of legitimacy to regulate the actions of policymakers.

To begin, the typical approaches to legitimacy reify the construct. They treat legitimacy as something concrete, which it is not. Legitimacy is not a fundamental phenomenon akin to the fundamental physical interactions of the universe, such as gravitational force or electromagnetic force, that hold true irrespective of human activity. The principle of preservation is probably the closest thing to a fundamental social principle. People will tend to act and leverage whatever agency and power available to them in pursuit of self-preservation or the preservation of a larger self-interest. To quote Thucydides – “The powerful exact what they can, and the weak have to comply.” This quote is from Thucydides’ History and has traditionally been translated as “The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must,” which Beard (2013, pp. 32-34) argues is a mistranslation. There is no absolute standard of legitimacy. There are only what actions constituents will and will not allow government officials to do, the reasons constituents will and will not allow government officials to do them, and the consequences of defying the will of the people.

Another concern is that the goal of satisfying economic criteria as a requirement for legitimacy is itself a normative criterion. There is no reason that people could not or should not use other criteria to make judgments about legitimacy. Only a small portion of the population is likely to even have a sufficient understanding of economic theory. Moreover, there is no requirement that people apply economic theory as the basis for judgments about the legitimacy of government actions even when it is explained to them.

There are in fact several types of rationality that one can apply to establish decision criteria for judging the legitimacy of government actions (Dunn, 2016). Economic efficiency is often used as the criterion for selecting policy prescriptions. However, basing such decisions on whether an alternative achieves a valued outcome irrespective of how efficiently it uses resources (i.e., effectiveness) or the extent to which a given level of a valued outcome satisfies a specific standard irrespective of economic efficiency (i.e., adequacy) are also justifiable decision-making criteria.

Additionally, Suchman’s (1995) proposition that individuals make assessments about legitimacy irrespective of the concerns of others does not correspond with what has been empirically demonstrated about human behavior. Judgments about legitimacy are essentially choice decisions. There is a socio-political dimension to decision-making and social processes such as sensemaking and sensegiving are important factors (Balogun, Pye, & Hodgkinson, 2008; Hodgkinson & Starbuck, 2008). Sociological phenomena can even distort the judgments of individuals (Asch, 1951; Asch, 1956).

Observations about the nature of legitimacy as a group assessment raise logical questions. To what end is legitimacy pursued in the context of technology transfer? What happens when a significant portion of the populous deems the government’s actions in a given policy domain such as technology transfer to be illegitimate? Moreover, how much does legitimacy even matter when it comes to technology transfer policy?

Most philosophical approaches treat political legitimacy as a regulative ideal, and often an unattainable one (Greene, 2019). It is a normative principle to which people should aspire but often fall short. These treatments of legitimacy seem to imply an all-or-nothing dichotomy in which an institution and its actions are either legitimate and accepted or illegitimate and rejected in their entirety. This conceptualization is not very useful from a practical perspective. It constrains research on the topic and reduces the usefulness of the construct as a guide for elected representatives and policymakers.

While conceptualizing social concepts as binary presence-absence dichotomies is a useful way to understand them, social phenomena often manifest in terms of degree (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). As such, one technology transfer policy can tend towards legitimacy and another technology transfer policy can tend toward illegitimacy with neither of them being completely legitimate nor completely illegitimate. Moreover, the consequences of the government pursuing actions regarding technology transfer that are more on the illegitimate end of the spectrum may not be as severe as pursuing analogously illegitimate actions in other areas. These are important nuances that seem to have been lost in the general discourse about political legitimacy and debates about technology transfer policy.

There is research that attempts to create knowledge about legitimacy that is more practically oriented and instrumental. Scholars have undertaken empirically based research that aims to shed light on when and why citizens follow the directives of their political representatives. Much of this research argues that legitimacy is casual for compliance (Tyler 2019). However, some have raised significant challenges to that conclusion (Lenowitz, 2019). But at the very least, Tyler and other researchers have empirically demonstrated that “individuals are more likely to comply, cooperate, and positively engage with the law when they feel obligated to obey it, when they trust their legal authorities, and when they believe they share moral values with the law and its enforcers, and this effect is greater than when individuals are simply worried about getting punished for law-breaking” (Lenowitz, p. 320). Thus the question becomes under what conditions will people feel obligated to obey and trust their legal authorities and what causes people to believe that laws reflect their moral values?

Although the above findings of empirical research about political legitimacy are important, they do not necessarily explain what is likely to happen if a significant constituency judges that a technology transfer policy is not legitimate. Social phenomena are subject to asymmetrical causal outcomes (Ragan, 2000). It is highly likely that the conditions that would cause individuals to judge a technology transfer policy to be illegitimate are not simply the mirror image of the conditions that would cause them to judge a technology transfer policy to be legitimate. Likewise, the behaviors of individuals who judge a technology transfer policy to be illegitimate probably do not conform to an all-or-nothing conception of the possible responses to illegitimacy.

The fact of the matter is that even strongly held beliefs or judgments do not necessarily motivate behavior (Lenowitz, 2019). For example, many people believe that one should abide by marital fidelity to their spouse. Yet many of them fail to behave accordingly. Thus, although constituents might strongly believe that a technology transfer policy, or set of policies, is not legitimate for the government to pursue, they still may not act on those beliefs.

An Alternative Conceptualization

An alternative proposition is that legitimacy is not so much attained, but that illegitimacy is avoided. In this sense, one can conceptualize legitimacy as a perceived characteristic of a government institution or its actions. It is the perception of an individual or group of individuals that an institution or its actions are not egregiously inappropriate according to the norms of society and thus do not warrant “rebellious action” against the institution. Illegitimacy (i.e., not legitimate) is the perception of an individual or group of individuals that a government institution or its actions are egregiously inappropriate according to the norms of society so much so that they are willing to take “rebellious action” against the institution. In effect, people tend to tacitly assume the legitimacy of government policy. By analogy, they act like scientists testing the null hypothesis that an action of the government is legitimate. They only discard it in favor of the alternative hypothesis that an action of the government is not legitimate if significant evidence causes them to do so. As such, the question becomes what constitutes such evidence?

Theorists posit that people do not assess the legitimacy of the individual actions of a government in isolation. That is, constituents do not assess the legitimacy of a government policy in a stand-alone fashion. However, constituents may deem any given policy at any given time to be illegitimate in the context of the totality of government actions. A single policy could become the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back” and cause a significant majority of constituents to assess the policy, or even the institution itself, to be illegitimate.

By way of analogy, think of illegitimacy as a large container suspended over the heads of policymakers by twine – something akin to the sword of Damocles. The Sword of Damocles is an apocryphal anecdote in which Dionysius II of Syracuse demonstrates to Damocles the constant looming danger that he faces as a ruler by having Damocles sit on the king’s throne not realizing, until Dionysius makes him aware, that a sword hangs above held at the pommel only by a single hair from a horse’s tail (Wikipedia contributors, 2022-August-1). In the absence of actions that constituents consider inappropriate, all is well. The container remains suspended, and the policymakers are unaffected. But for every action that constituents do find inappropriate, weight is added to the container and the amount of weight added depends on the degree of the infraction. Weight is removed from the container based on the amount of time that elapses between infractions. But if too much weight accumulates in the bucket the twine will break, and the weight-filled container will fall on the policymakers causing significant harm.

One can further posit that in making judgments about the legitimacy of a government and its actions, people filter their observations and the information they receive through the lens of morality tales. One or more morality tales, or combinations thereof, serve as a referent to help people make sense of the institution and its actions. How well a policy aligns with a person’s ideology will influence whether they perceive it to be legitimate or not.

In addition to the influence of one’s own cognitive processes on judgments about political legitimacy, social constructionism suggests that people influence one another’s judgments about legitimacy. In the course of everyday life, people comprehend reality through a variety of typifications that are more abstract as they become more physically and temporally removed from the individual (Berger & Luckmann, 1966). Social order is an ongoing human production (Berger & Luckmann), thus judgments about political legitimacy are ongoing human productions as well.

With this alternative conceptualization of political legitimacy, it becomes necessary to reconsider the possible actions and outcomes when people deem a government institution or policy to be illegitimate. The American political framework affords people recourse short of armed revolt in the face of illegitimate government action. One can think of the political order as consisting of three tiers (see

Figure 5). Action can be taken in response to illegitimate government behavior at any of these tiers. However, determining whether citizen actions that are taken against a policy, policymaker, or political framework are indications that people consider them not to be illegitimate requires one to consider the reasons for the actions.

At the lowest level, people may rebel against the policy that they believe is not legitimate. If a person considers a policy legitimate, they will accept it as the way things are even if they disagree with the policy. That is, the person will not act rebelliously against the policy even if they disagree with it. However, if a person does judge a policy to be illegitimate, there is a spectrum of rebellious actions they could take from subversive action against the policy to actively working to end or replace the policy. For example, individuals and coalitions might file lawsuits against the government to overturn what they consider to be illegitimate policies or prevent them from taking effect.

People may also rebel against policymakers that they believe have pursued illegitimate policies. The simplest action they can take is to simply withdraw their support by either not voting or voting for another candidate during elections. More severe actions that a person can take include financially supporting opposition candidates and advocacy groups and campaigning against an incumbent.

Finally, people can rebel against the political framework if they believe the situation to be so dire that it cannot be corrected through action at the lower tiers of the political order alone. The quintessential example is probably the American revolution in which the colonies broke away from England through armed revolt and established a new political order because a significant portion of the colonists judged the actions of England to be illegitimate and unlikely to be satisfactorily corrected through less drastic means. A less extreme example is civilian protests at the local level that put pressure on elected officials to make changes such as the Montgomery bus boycott from 1955 to 1956 during the civil rights movement that inspired legal challenges and led to changes in policy regarding racial segregation on public transportation. A more recent example is the protests in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, which led to Department of Justice investigations into the city’s policing practices and the subsequent implementation of reforms.

When formulating and implementing technology transfer policy, or any policy for that matter, one goal of elected representatives and policymakers is to avoid potential undesired consequences associated with illegitimacy. Reconceptualizing and applying Suchman’s (1995) typology of legitimacy (see

Figure 1) can possibly facilitate achieving this goal. Instead of thinking of it as a classification of the various kinds of legitimacy, one can think of legitimacy (or “not illegitimate”) as the outcome and the various subtypes as causal conditions that can be conjunctively combined to produce the perception of legitimate or illegitimate action. Assuming causal complexity applies, then the various conditions or conjunctions of conditions are either necessary or sufficient to produce legitimacy and avoid illegitimacy. Another way to reinterpret Suchman’s typology is to think of legitimacy as a higher-order construct and the various subtypes as components or dimensions of that higher-order construct rather than as just distinct types of legitimacy.

Applying this reconceptualization, the traditional normative argument for the legitimacy of technology transfer policy is based on the presence of transactional and ethical conditions. It essentially argues that exchange, influence, and consequential conditions are present and thus government action in technology transfer is appropriate. Again, this approach reifies the construct of legitimacy. An alternative interpretation that attempts to avoid reifying the construct of legitimacy is that the traditional argument assumes the conjunction of exchange, influence, and consequential conditions is sufficient to produce the perception of legitimacy and avoid the perception of illegitimacy.

Discussion

The preceding section presented an alternative conceptual framework for examining the legitimacy of technology transfer policy. This section aims to interpret the examination of the preceding section. It provides an understanding of how the new perspective helps explain the legitimacy of government intervention in technology transfer and how the new perspective might affect policymaking as well as future policy research.

The examination of the legitimacy of government intervention in technology transfer sought to answer four primary questions. First, on what basis can policymakers claim that government intervention in technology transfer is a legitimate use of the power and authority of government? Second, what are the limits to the kinds of technology transfer problems that the government can claim are its legitimate concerns? Third, what are the parameters for the kinds of solutions to those technology transfer problems that policymakers can claim are legitimate options? And finally, what are the likely consequences if policymakers take actions that a significant majority of constituents consider illegitimate uses of the power and authority of the government?

It seems that the basis for which policymakers can claim that government intervention in technology transfer is politically legitimate can be more broad-based than what is traditionally used. Economic rationality is not the only basis for making such claims. Effectiveness and adequacy as related to desired social outcomes can also provide a basis for claiming the legitimacy of government intervention in technology transfer. Moreover, there are a number of other sociological and psychological levers that policymakers can leverage to claim the legitimacy, or avoid the perception of illegitimacy, of technology transfer policy.

An implication of the alternative conceptualization above is that political legitimacy is likely far more malleable than previously believed. This significantly expands the range of potential technology transfer problems with which the government can rightly concern itself as well as the kinds of solutions that policymakers can justifiably consider for addressing those problems. The only real limit is the degree to which policymakers can influence the long-term perceptions of constituents and avoid the perception of illegitimacy. Moreover, actions other than just regulation can be considered to address the problem.

Finally, the likely consequences of policymakers taking actions to encourage and facilitate technology transfer that a significant majority of constituents consider illegitimate are likely to be more nuanced and less drastic than what the traditional discourse on political legitimacy would imply. The most likely consequence is legal action against specific policies. Challenges to the incumbency of policymakers driven by the perceived illegitimacy of a given policy are probably unlikely given the low saliency of the topic for many constituents. As such, there is probably an opportunity for policymakers to be far more aggressive with technology transfer policy than what they have traditionally been.

Value and Merits

The proposed conceptual framework adds value to the field of technology transfer in several ways. Relative to other approaches, it transforms political legitimacy from an unattainable normative theoretical construct into a practical concept that can be applied instrumentally. The discourse on political legitimacy has been heavily rooted in conceptions of morality and what “ought” to be. This conceptualization nudges the discussion toward what is and what will be. Reification of the construct of political legitimacy has led scholars to frame issues as a question of “What government actions are legitimate and what government actions are illegitimate?” However, a more useful question is “Why do constituents accept a government action as legitimate or deem government actions to be sufficiently illegitimate to warrant rebellious action?”

Additionally, the alternative conceptual framework described above can potentially affect technology transfer practice and research. It paves the way for policymakers to address broader technology transfer problems and pursue more creative and impactful policy options. It enables broader problem-structuring analyses. Moreover, the implementation of new policies will undoubtedly affect the way technology transfer is practiced, ideally for the better.

Implications

There are several propositions that one can logically deduce from the alternative conceptualization of political legitimacy described in this paper. First, policymakers may be able to use narratives to influence the judgments of constituents about the legitimacy or illegitimacy of technology transfer policy. Political legitimacy is an aspect of perceived reality, which is socially constructed. Much of this social construction is driven by communication, which is heavily comprised of narratives.

The range of policy options that people are probably willing to accept likely varies based on the policy problem domain. As previously discussed, strong feelings about an issue do not necessarily result in actions. As such, only those policies that exceed a certain salience threshold will spur constituents to act against government intervention that they believe is inappropriate. When it comes to technology transfer, there may be a greater range of policy options available to policymakers than most currently assume. This is primarily because the topic is less salient to the general public. Policies regarding less salient topics are likely to receive less scrutiny. Consequently, constituents are likely to give the government more leeway in the type and degree of actions it can pursue. The perceptions of interest groups are likely to be of more relevance. There appear to be few interest groups that would oppose more government intervention to encourage and facilitate an increased level of technology transfer based on perceptions of political legitimacy.

Limitations of the Analysis

The analysis above has two primary limitations. The conclusions are principally based on existing literature rather than empirical data. Consequently, the reliability of the conclusions has not been established. Also, as a conceptual investigation, by its very nature, the analysis is more susceptible to error and subjectivity than an empirical study. Again, this is because the conclusions are predominantly drawn from existing literature and reason and do not rely on empirically derived data.

Recommendations for Future Research

Applying this alternative conceptual framework may help address pertinent research problems in the field of technology transfer. For example, the U.S. government has sought ways to increase the incidence of technology transfer since the end of the Second World War. Perceptions of what actions are politically legitimate options are a significant constraint on the extent of these efforts. The alternative conceptual framework that this paper presents enables policy analysts to empirically evaluate whether those perceptions are accurate or overly restrictive. If they are overly restrictive, it suggests that policymakers have far more latitude to intervene in technology transfer than initially thought.

The proposed conceptual framework may also support future efforts to develop theories regarding both technology transfer and political legitimacy. Greater clarity regarding the boundaries of legitimate actions of the government within the domain of technology transfer will expand the kinds of phenomena that scholars can justifiably investigate. This will enable the generation of new insights that will support theory development.

The alternative conceptualization will also support the further empirical investigation of political legitimacy to answer several pertinent questions. Given that political legitimacy is a social phenomenon, it is likely subject to causal complexity. Configurational comparative methods can be applied to the framework in

Figure 1 to examine which dimensions are necessary or sufficient to produce perceptions of legitimacy or illegitimacy. Other questions that can be further examined include whether and to what degree the salience of an issue influences the judgments of constituents about the legitimacy of government action, to what degree are certain dimensions of political legitimacy more malleable than others, and what narrative strategies are most effective in influencing judgments about political legitimacy?

Conclusions

This paper has presented a reconceptualization of political legitimacy in the context of technology transfer policy. It reimagined political legitimacy as less of an unattainable normative principle of limited practical value to policymakers and more of a descriptively understood social phenomenon that policymakers can apply instrumentally to formulate not only technology transfer policy but other kinds of public policy as well. The analysis illuminated several concerns and challenges regarding the traditional approach to understanding whether specific government interventions in technology transfer are legitimate or illegitimate. It subsequently applied social constructionism and morality tales to describe an alternative conceptualization of political legitimacy that integrates aspects of other frameworks. The paper concluded by briefly discussing the implications of the alternative conceptual framework for technology transfer policy and practice as well as potential avenues for future research.

Funding

The author did not receive funding support from any organization to assist with this work or the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2022). Defense, nondefense, and total R&D, 1976-2023 [Data file]. Retrieved January 8, 2023 from https://www.aaas.org/programs/r-d-budget-and-policy/historical-trends-federal-rd.

- Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men; Research in human relations. (pp. 177-190). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

- Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs. 70(9): 1-70. [CrossRef]

- Balogun, J., Pye, A., & Hodgkinson, G. P. (2008). Cognitively skilled organizational decision making: Making sense of deciding. In G. P. Hodgkinson & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational decision making (pp. 234-249). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Beard, M. (2013). Confronting the classics: Traditions, adventures, and innovations. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Blankesteijn, M., & Bossink, B. (2020). Assessing the legitimacy of technological innovation in the public sphere: Recovering raw materials from wastewater. Sustainability, 12(22), 9408. [CrossRef]

- Branscomb, L. M. (1992). Does America need a technology policy? Harvard Business Review, 70(2), 24-31.

- Broughel, J., & Thierer, A. D. (2019). Technological innovation and economic growth: A brief report on the evidence. Mercatus Research Paper. Retrieved January 6, 2022 from https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/broughel-technological-innovation-mercatus-research-v1.pdf.

- Carlaw, K. I., & Lipsey, R. G. (2003). Productivity, technology and economic growth: What is the relationship? Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(3), 457-495. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J. R., Swan, L. K., & Heesacker, M. (2014). Better off than we know: Distorted perceptions of incomes and income inequality in America. Psychological Science, 25(2), 613-618. [CrossRef]

- Chantrill, C. (2023). U.S. federal budget analyst: FY24 federal budget spending actuals for fiscal years 2017-2022. U.S. Spending. Retrieved from January 8, 2023 from https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/federal_budget_detail_2022bs22022n_60704041_605_609#usgs302.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Historical budget data: Supplement to the budget and economic outlook: 2022 to 2032 [Data file]. Retrieved from January 8, 2023 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#2.

- Desmarais-Tremblay, M. (2017). A genealogy of the concept of merit wants. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 24(3), 409-440. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M., & Western, B. (2018). Poverty in America: New directions and debates. Annual review of sociology, 44, 305-318. [CrossRef]

- Greene, A. R. (2019). Is political legitimacy worth promoting? In J. Knight & M. Schwartzberg (Eds.), Political Legitimacy (pp. 65-101). New York, NY: New York University Press. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, G. P., & Starbuck, W. H. (Eds.). (2008). The Oxford handbook of organizational decision making. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Iceland, J. (2013). Poverty in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Jones, M. D., McBeth, M. K, & Shanahan, E. A. (2014). Introducing the Narrative Policy Framework. In M. D. Jones, M. K. McBeth & E. A. Shanahan (Eds.), The science of stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework in public policy analysis (pp. 1-25). Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. (2018). Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals (A. W. Wood, Trans.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (Original work published 1785).

- Lall, S. (Ed.) (2001). The economics of technology transfer. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

- Lenowitz, J. A. (2019). On the empirical measurement of legitimacy. In J. Knight & M. Schwartzberg (Eds.), Political Legitimacy (pp. 293-327). New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Libecap, G. D. (Ed.) (2009). Measuring the social value of innovation: A link in the university technology transfer and entrepreneurship equation (Vol. 19). Bingly, United Kingdom: Jai Press.

- Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2019). The economic benefits of technology transfer from U.S. federal laboratories. The Journal of Technology Transfer (5), 1416. [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, S. W., & Foss, K. A. (2009). Social construction of reality. In Encyclopedia of communication theory (Vol. 1, pp. 892-894). SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, R. A. (1959). The theory of public finance: A study in public economy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. (2022). Federal funds for research and development, fiscal years 2020-21 [Data file]. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 29, 2022 from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/fedfunds/.

- Novaro, F. P. A., de Lima Amaral, E. F., Huang, H., & Price, C. C. (2016). Inequality and opportunity: The relationship between income inequality and intergenerational transmission of income. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Ragin, C. C. (2000). Fuzzy-set social science. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Ragin, C. C., & Amoroso, L. M. (2011). Constructing social research: The unity and diversity of method. Newbury Park, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Rank, M. R., Eppard, L. M., & Bullock, H. E. (2021). Poorly understood: What America gets wrong about poverty. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Reich, R. B. (1987). Tales of a New America. New York, NY: Times Books.

- Rosenberg, N. (2020). Technology and American economic growth. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ryscavage, P. (2015). Income Inequality in America: An Analysis of Trends: An Analysis of Trends. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Schrier, E. (1964). Toward Technology Transfer: The Engineering Foundation Research Conference on “Technology and the Civilian Economy.” Technology and Culture, 5(3), 344-358. [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E., (2000). Economics of the public sector (3th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Stiglitz, J., & Rosengard, J. (2015). Economics of the public sector (4th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Trover, L. (2011). Legitimacy. In G. Ritzer & M. J. Ryan (Eds.), The concise encyclopedia of sociology (pp. 350). Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Tyler, T. R. (2019). Evaluating consensual models of governance: Legitimacy-based law. In J. Knight & M. Schwartzberg (Eds.), Political Legitimacy (pp. 257-292). New York, NY: New York University Press.

- United Nations. (2021). GDP and its breakdown at current prices in U.S. dollars [Data file]. Retrieved January 8, 2023 from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama/Downloads.

- U.S. Spending. (n.d.) U.S. Government Spending. Retrieved from https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/year_spending_2018USbn_20bs2n_4041_605#usgs302.

- Weber, M. (1958). The three types of legitimate rule (Hans Gerth, Trans.). Berkeley Publications in Society and Institutions, 4(1), 1-11. (Original work published 1922).

- Wijnberg, N. M. (1994). Art and technology: A comparative study of policy legitimation. Journal of Cultural Economics, 18(1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors. (2022, May 31). Categorical imperative. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Categorical_imperative&oldid=1090840866.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2022, August 1). Damocles. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Damocles&oldid=1101709780.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).