Submitted:

30 January 2023

Posted:

31 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

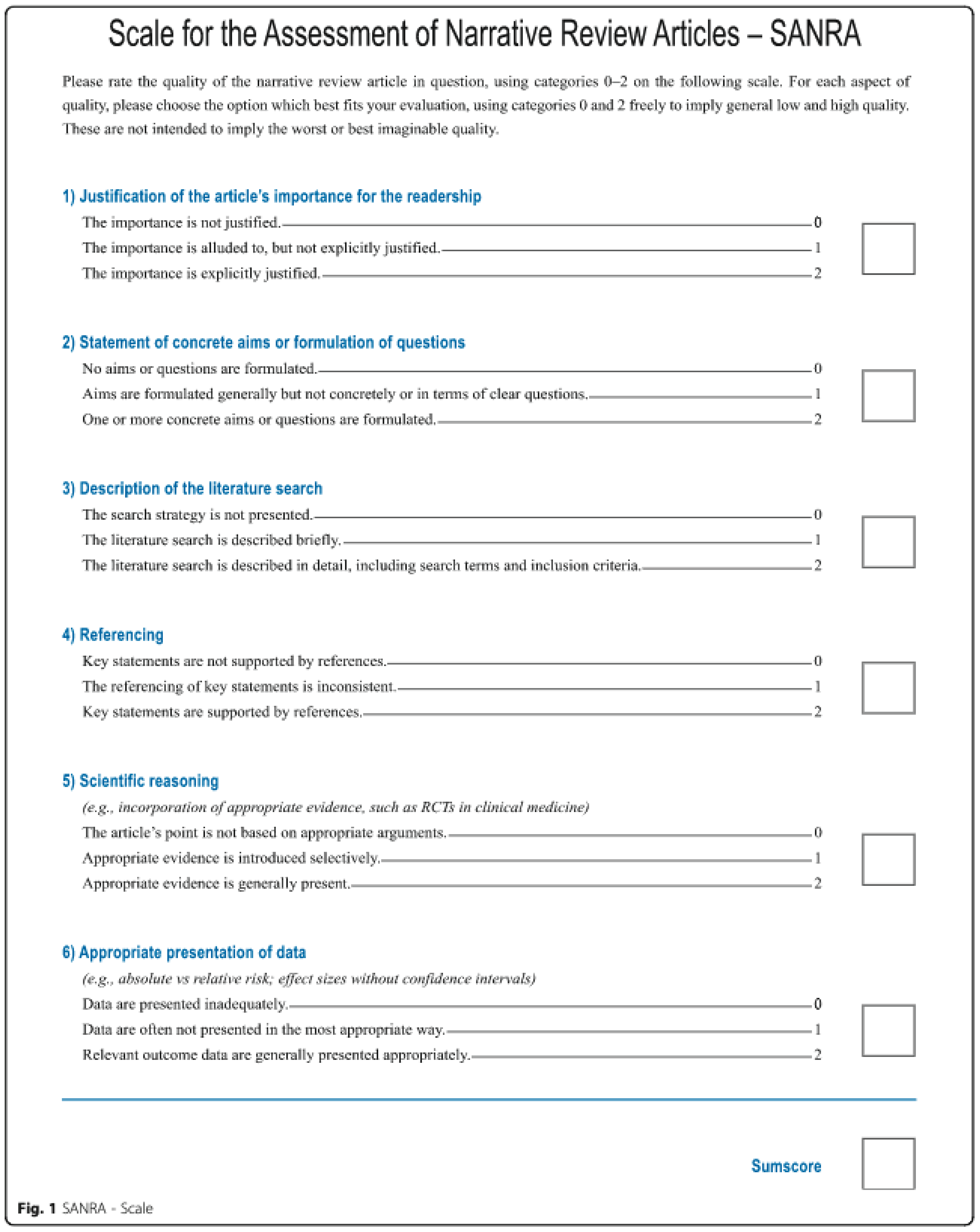

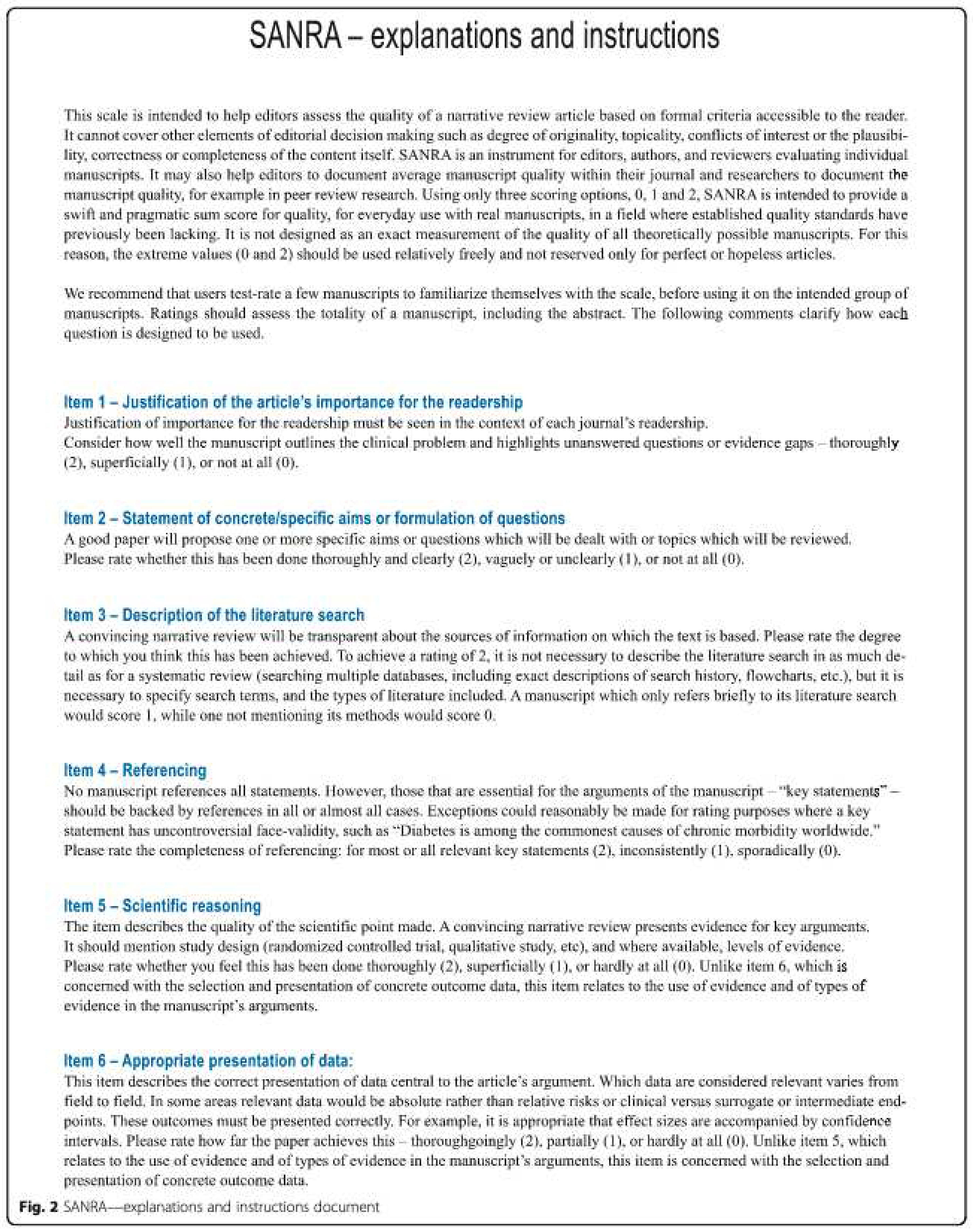

2.1. Narrative review methodology

2.1.1. Item 1—Justification of the article’s importance for the readership

2.1.2. Item 2 – Statement of concrete/specific aims or formulation of questions

2.1.3. Item 3 – Description of the literature search

Search strategy

Database

Screening process

Data extraction

Data analysis and synthesis

2.1.4. Item 4 – Referencing

2.1.5. Item 5 – Scientific reasoning

2.1.6. Item 6 – Appropriate presentation of data

3. Results

3.1. Undergraduate nursing education

3.1.1. Definitions of undergraduate nursing students

3.1.2. Use of digital technologies in undergraduate nursing education

3.1.3. Faculty responses to digital technologies in undergraduate nursing education

3.2. Digital literacy

3.2.1. Definitions and relevance of digital literacy

3.2.2. Development of digital literacy in undergraduate nursing education

3.3. The Digital Native

3.3.1. Descriptions of the Digital Native

3.3.2. Digital Native assumptions

3.3.3. Digital Native criticisms

4. Discussion

4.1 The history of the Digital Native

4.1.1 The Digital Native debate

4.1.2 Higher Education responses to the Digital Native debate

4.2 Digital literacy

4.2.1 Defining digital literacy

4.2.2 Institutional responses to Digital Literacy

WHO – World Health Organization

Jisc – formerly the Joint Information Systems Committee

- Information Literacy – the capability to find, critique and manage information

- ICT Literacy – the capability to adopt, adapt and use digital technologies

- Learning Skills – the capability to learn and study in a digital technology environment

- Digital Scholarship – the capability to participate in academic, research and professional environments that use digital technologies

- Media Literacy – the capability to critique and create academic and professional information using digital technologies

- Communications and collaboration – the capability to participate in digital environments for education and research, and

- Career and identity management – the capability to develop and manage a professional digital identity [98].

NMC – New Media Consortium

4.2.3. Higher Education responses to Digital Literacy

4.3 Implications of the Digital Native narrative on the digital literacy of undergraduate nursing students

4.4 Recommendations

- A global set of core Nurse Educator Digital Literacy competencies are identified, that can be contextualised to individual jurisdictions.

- National Nursing Accreditation agencies adopt and contextualise National Nurse Educator Digital Literacy competencies, and require all nurse academics to demonstrate their digital literacy competency accordingly.

- Nurse Educator Digital Literacy competencies are recognised and aligned with existing, national digital health competency frameworks.

- National Nursing Digital Literacy competencies for entry into practice as a Registered Nurse be developed and adopted, cognisant of the existing global efforts and frameworks, to inform undergraduate nursing curricula.

- National Nursing Accreditation and registration agencies update undergraduate course accreditation guidelines that reflect the development and assessment of the National Nursing Digital Literacy competencies.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A [18]

References

- World Economic Forum. New Vision for Education - Unlocking the Potential of Technology. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEFUSA_NewVisionforEducation_Report2015.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Jisc (formerly Joint Information Systems Committee). Developing digital literacies. Available online: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-digital-literacies (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Ng, W. Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Comput Educ 2012, 59, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W. Empowering scientific literacy through digital literacy and multiliteracies; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, B.; Adams Becker, S.; Cummins, M.R. Digital Literacy > An NMC Horizon Project Strategic Brief; NMC - New Media Consortium: Austin, Texas, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, G.; Thomas, A.; Beach, B. Creating a Connected Future Through Information and Digital Literacy: Strategic Directions at The University of Queensland Library. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. Defining digital literacy - What do young people need to know about digital media? Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2015, 10, 21–35. Available online: https://www.idunn.no/file/pdf/66808541/defining_digital_literacy_-_what_do_young_people_need_to_kn.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.I.; Serpa, S. The Importance of Promoting Digital Literacy in Higher Education. Int. J. Soc. Sci 2017, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.C.; Perez, J. Unraveling the digital literacy paradox: How higher education fails at the fourth literacy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2014, 11, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, V. Natives, immigrants, residents or visitors - Developing a student-led understanding of the role of digital literacies in the curriculum. In Proceedings of the International Enhancement Themes Conference 2013, Scotland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P.A.; De Bruyckere, P. The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teach Teach Educ 2017, 67, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. Horiz. 2001, 9. Available online: https://marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf.

- Boechler, P.; Dragon, K.; Wasniewski, E. Digital Literacy Concepts and Definitions: Implications for Educational Assessment and Practice. Int. J. digit. lit. digit. competence 2014, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingli, A.; Seychell, D. The new digital natives: cutting the chord; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ECDL (European Computer Driving Licence). The Fallacy of the ‘Digital Native’: Why Young People Need to Develop their Digital Skills. Available online: https://www.icdleurope.org/policy-and-publications/the-fallacy-of-the-digital-native/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Thompson, P. The Digital Natives as Learners: Technology Use Patterns and Approaches to Learning. Comput Educ 2013, 65, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L.; Maeder, A.; Button, D.; Breaden, K.; Brommeyer, M. Defining Nursing Informatics: A Narrative Review. Stud Health Technol Inform 2021, 284, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. integr. peer rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, H.; Glasziou, P.; Chalmers, I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: How will we ever keep up? PLoS medicine 2010, 7, e1000326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Australian Nursing & Midwifery Accreditation Council (ANMAC). Registered Nurse Accreditation Standards 2019; Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council: Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Qualifications Framework Council. Australian Qualifications Framework (Second Edition); Adelaide, South Australia, 2013.

- Reid, L.; Button, D.; Breaden, K.; Brommeyer, M. Nursing informatics and undergraduate nursing curricula: A scoping review protocol. Nurse Educ Pract 2022, 65, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkey, K.; Kaminskil, J. What do Nursing Students’ Stories Reveal about the Development of their Technological Skills and Digital Identity? A Narrative Inquiry. Can J Occup Ther 2020, 15, https://cjni.net/journal/–p=6831. [Google Scholar]

- Nsouli, R.; Vlachopoulos, D. Attitudes of nursing faculty members toward technology and e-learning in Lebanon. BMC Nursing 2021, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stec, M.; Bauer, M.; Hopgood, D.; Beery, T. Adaptation to a Curriculum Delivered via iPad: The Challenge of Being Early Adopters. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2018, 23, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaya-Moreno, M.F.; Pérez-Cañaveras, R.M. Social Media Used and Teaching Methods Preferred by Generation Z Students in the Nursing Clinical Learning Environment: A Cross-Sectional Research Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Romanello, M.L. Generational Diversity: Teaching and Learning Approaches. Nurse Educ 2005, 30, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkiszewski, P.; Pollitt, P.; Leonard, A.; Lane, S.H. Reaching Millennials With Nursing History. Creat Nurs 2016, 22, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharoff, L. Integrating YouTube into the Nursing Curriculum. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2011, 16, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houwelingen, C.T.M.; Ettema, R.G.A.; Kort, H.S.M.; ten Cate, O. Internet-Generation Nursing Students' View of Technology-Based Health Care. J Nurs Educ 2017, 56, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, D.; Welsh, D.; Wiggins, A.T. Learning Preferences and Engagement Level of Generation Z Nursing Students. Nurse Educ 2020, 45, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.T.; Martin, T.; White, J.; Elliott, R.; Norwood, A.; Mangum, C.; Haynie, L. Generational (age) differences in nursing students' preferences for teaching methods. J Nurs Educ 2006, 45, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, C.M.; Levett-Jones, T.; Lapkin, S.; Warren-Forward, H. Generation Y Health Professional Students’ Preferred Teaching and Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review. Open j. occup. ther. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, C.A.; Cheng, C.; Douglas, T.; Elsworth, G.; Osborne, R. eHealth Literacy of Australian Undergraduate Health Profession Students: A Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupanic, M.; Rebacz, P.; Ehlers, J.P. Media Use Among Students From Different Health Curricula: Survey Study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Success in information technology – what do student nurses think it takes? A quantitative study based on Legitimation Code Theory. Res. Learn. Technol. 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatto, B.; Erwin, K. Moving on from Millennials: Preparing for generation Z. J Contin Educ Nurs 2016, 47, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Chan, V.; Rajendran, P.; Ang, E. Learning styles, preferences and needs of generation Z healthcare students: Scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, R.O. Teaching the net set. J Nurs Educ 2009, 48, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiba, D.J.; Barton, A. Adapting Your Teaching to Accommodate the Net Generation of Learners. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2006, 11, 5. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17201579/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiba, D.J. The Millennials: Have They Arrived at Your School of Nursing? Nurs Educ Perspect 2005, 26, 370–371. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, D.J. Digital Wisdom: A Necessary Faculty Competency? Nurs Educ Perspect 2010, 31, 251–253. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/neponline/Citation/2010/07000/Digital_Wisdom_A_Necessary_Faculty_Competency_.14.aspx. [PubMed]

- Vitvitskaya, O.; Suyo-Vega, J.A.; Meneses-La-Riva, M.E.; Fernández-Bedoya, V.H. Behaviours and Characteristics of Digital Natives Throughout the Teaching-Learning Process: A Systematic Review. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 11, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voge, C.; Hirvela, K.; Jarzemsky, P. The (Digital) Natives Are Restless: Designing and Implementing an Interactive Digital Media Assignment. Nurse Educ 2012, 37, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, V.P. Education in urban communities in the United States: Exploring the legacy of Lawrence A. Cremin: Urbanisation and education: the city as a light and beacon? Paedagog Hist 2003, 39, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. Teach with digital technologies. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/digital/Pages/teach.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Bembridge, E.; Levett-Jones, T.; Jeong, S.Y.-S. The preparation of technologically literate graduates for professional practice. Contemp Nurse 2010, 35, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicca, J.; Shellenbarger, T. Connecting with Generation Z: Approaches in Nursing Education. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2018, 13, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.A. Integrating Informatics in Undergraduate Nursing Curricula: Using the QSEN Framework as a Guide. J Nurs Educ 2012, 51, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, M.; Shellenbarger, T. Influential Factors and Perceptions of eHealth Literacy among Undergraduate College Students. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2014, 18. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1732549790?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Shamsaee, M.; Shahrbabaki, P.M.; Ahmadian, L.; Farokhzadian, J.; Fatehi, F. Assessing the effect of virtual education on information literacy competency for evidence-based practice among the undergraduate nursing students. BMC Medical Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earle, V.; Myrick, F. Nursing Pedagogy and the Intergenerational Discourse. J Nurs Educ 2009, 48, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangold, K. Educating a New Generation: Teaching Baby Boomer Faculty About Millennial Students. Nurse Educ 2007, 32, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belchez, C.A. Informatics and Faculty Intraprofessional Assessment and Gap Analysis of Current Integration of Informatics Competencies in a Baccalaureate Nursing Program. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2019.

- American Library Association Digital Literacy Taskforce. What is Digital Literacy. Available online: https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/16260 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Christodoulou, E.; Kalokairinou, A.; Koukia, E.; Intas, G.; Apostolara, P.; Daglas, A.; Zyga, S. The Test - Retest Reliability and Pilot Testing of the "New Technology and Nursing Students' Learning Styles" Questionnaire. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 8, 567–576. Available online: https://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/6_Christodoulou_original_8_3.pdf.

- Pieterse, E.; Greenberg, R.; Santo, Z. A Multicultural Approach to Digital Information Literacy Skills Evaluation in an Israeli College. Commun. Inf. Lit. 2018, 12, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? Horiz. 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, P. The mystery of the digital natives' existence: Questioning the validity of the Prenskian metaphor. First Monday 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D. Growing up digital: The rise of the net generation; McGraw-Hill.: New York, New York City, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2021 Census shows Millennials overtaking Boomers. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-shows-millennials-overtaking-boomers (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Rowlands, I.; Nicholas, D.; Williams, P.; Huntington, P.; Fieldhouse, M.; Gunter, B.; Withey, R.; Jamali, H.R.; Dobrowolski, T.; Tenopir, C. The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib proceedings 2008, 60, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Maton, K.; Kervin, L. The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. Br J Educ Technol 2008, 39, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Czerniewicz, L. Debunking the 'digital native': beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. J Comput Assist Learn 2010, 26, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Y. Talkin’ ‘bout my generation: a brief introduction to generational theory. Planet 2009, 21, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine,. Are Generational Categories Meaningful Distinctions for Workforce Management? 2020. Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25796/are-generational-categories-meaningful-distinctions-for-workforce-management.

- Kriegel, A. Generational Difference: The History of an Idea. Daedalus 1978, 107, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frawley, J.K. The myth of the 'digital native'. Available online: https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/teaching@sydney/digital-native-myth/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Eynon, R. The myth of the digital native: Why it persists and the harm it inflicts. Educational Research and Innovation Education in the Digital Age Healthy and Happy Children 2020, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Digital natives: Where is the evidence? Br Educ Res J 2010, 36, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Listen to the Natives. Educ Leadersh 2006, 63, 8–13. Available online: https://files.ascd.org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el200512_prensky.pdf.

- King, A. Digital natives are a myth. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/news/c4de/digital-natives-are-a-myth (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Kim, E.J. The Influence of Digital Native Media Utilization and Network Homogeneity on Creative Expressive Ability in an Open Innovation Paradigm. TURCOMAT 2021, 12, 824–832. [Google Scholar]

- Mehran, P.; Alizadeh, M.; Koguchi, I.; Takemura, H. Are Japanese digital natives ready for learning english online? a preliminary case study at Osaka University: Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorney, G. Digital natives, and the death of another millennial myth. Available online: https://www.hrmonline.com.au/recruitment/digital-natives-death-another-myth/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Smith, E. The Digital Native Debate in Higher Education: A Comparative Analysis of Recent Literature / Le débat sur les natifs du numérique dans l'enseignement supérieur: une analyse comparative de la littérature récente. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2012, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutropoulos, A. Digital Natives: Ten Years After. J Online Learn Teach 2011, 7, 525. Available online: https://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no4/koutropoulos_1211.htm.

- Prensky, M. H. Sapiens Digital: From Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives to Digital Wisdom. Innovate: J.Online Educ 2009, 5. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/innovate/vol5/iss3/1.

- Sanders, C.K.; Scanlon, E. The Digital Divide Is a Human Rights Issue: Advancing Social Inclusion Through Social Work Advocacy. J. hum rights soc. work 2021, 6, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollman, A.K.; Obermier, T.R.; Burger, P.R. Rural Measures: A Quantitative Study of The Rural Digital Divide. J. Inf. Policy 2021, 11, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamuyu, P.K. Bridging the digital divide among low income urban communities. Leveraging use of Community Technology Centers. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.C.; Ramirez, P.C.; Sparks, P. Digital Inclusion and Digital Divide in Education Revealed by the Global Pandemic. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, M.I.; Mokwena, S.N.; Ilorah, A. The impact of digital divide for first-year students in adoption of social media for learning in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohemeng, F.L.K.; Ofosu-Adarkwa, K. Overcoming the Digital Divide in Developing Countries: An Examination of Ghana’s Strategies to Promote Universal Access to Information Communication Technologies (ICTs). J. Dev. Soc. 2014, 30, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. The digital native - myth and reality. Aslib proceedings 2009, 61, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, L.J.; Summers, J.; Lawrence, J.; Noble, K.G. Digital Literacy in Higher Education: The Rhetoric and the Reality. In Myths in Education, Learning and Teaching; Harmes, M.K., Huijser, H., Danaher, P.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, United Kingdom, 2015; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Daniela, L.; Visvizi, A.; Gutiérrez-Braojos, C.; Lytras, M.D. Sustainable Higher Education and Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL). Sustain. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Maton, K. Beyond the 'digital natives' debate: Towards a more nuanced understanding of students' technology experiences. J Comput Assist Learn 2010, 26, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L.; Godhe, A.-L.; Ledesma, A.G.L. What is digital literacy? A comparative review of publications across three language contexts. E-Learn. 2020, 17, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, J.K. Digital literacy : the quest of an inclusive definition. Read Writ. 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, D.; Scharber, C. Digital Literacies Go to School: Potholes and Possibilities. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2008, 52, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, R.; Méndez Leal, E.I. Digital Literacy Imperative. 2022.

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO | Global diffusion of eHealth: Making universal health coverage achievable; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening; 2019.

- Jisc (formerly Joint Information Systems Committee). Jisc - About us. Available online: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/about (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Watters, A. The Horizon Report: A History of Ed-Tech Predictions. Available online: https://hackeducation.com/2015/02/17/horizon (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Grussendorf, S. A critical assessment of the NMC Horizon reports project. Compass (Eltham) 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams Becker, S.; Brown, M.; Dahlstrom, E.; Davis, A.; DePaul, K.; Diaz, V. ; J., P. NMC Horizon Report: 2018 Higher Education Edition.; EDUCAUSE: Louisville, Colorado, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, L.; Hegarty, B.K., O.; Penman, M.; Coburn, D.; McDonald, J. Developing Digital Information Literacy in Higher Education: Obstacles and Supports. J. Inf. Technol. 2011, 10, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia's Health 2016. 2016. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9844cefb-7745-4dd8-9ee2-f4d1c3d6a727/19787-AH16.pdf.aspx. (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Chang, J.; Poynton, M.A.; Gassert, C.R.; Staggers, N. Nursing informatics competencies required of nurses in Taiwan. Int J Med Inform 2011, 80, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, D. An Exploration of Student and Academic Issues Relating to E-learning and its Use in Undergraduate Nursing Education in Australia: A Mixed Methods Inquiry. Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, 2017.

- Brown, J.; Morgan, A.; Mason, J.; Pope, N.; Bosco, A.M. Student Nursesʼ Digital Literacy Levels: Lessons for Curricula. Comput Inform Nurs 2020, 38, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, M.; Borycki, E.M.; Redmond, A. Developing Digital Literacies in Undergraduate Nursing Studies: From Research to the Classroom. In Health Professionals' Education in the Age of Clinical Information Systems, Mobile Computing and Social Networks; 2017; pp. 149-173.

- Sorensen, J.; Campbell, L. Curricular path to value: Integrating an academic electronic health record. J Nurs Educ 2016, 55, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callinici, T. Nursing Apps for Education and Practice. J Health Med Inform 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balenton, N.; Chiappelli, F. Telenursing: Bioinformation Cornerstone in Healthcare for the 21st Century. Bioinformation 2017, 13, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, M.; Skiba, D.J.; Bowman, J. Teaching nurses to provide patient centered evidence-based care through the use of informatics tools that promote safety, quality and effective clinical decisions. Consumer-Centred Coumputer-Supported Care for Healthy People 2006, 122, 230–234. Available online: https://ebooks.iospress.nl/publication/9194.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).