1. Introduction

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WON) is a serious local complication of severe acute necrotising pancreatitis. This type of necrosis can be intra-pancreatic, peri-pancreatic, or both [

1,

2]. An acute necrotic collection may resolve gradually over time or progress to an encapsulated necrotic collection or WON, which typically occurs 4 weeks or more after the onset of acute pancreatitis [

3]. WON can include various clinical presentations, such as abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, jaundice, weight loss, and infection [

4]. The treatment of symptomatic WON has undergone fundamental changes in recent years. Several studies have reported that the following minimally invasive approaches can achieve better outcomes: endoscopic transluminal drainage with or without necrosectomy; laparoscopic or retroperitoneal surgical approach; and radiology-guided percutaneous approach followed by necrosectomy [

5,

6,

7]. The endoscopic step-up approach, which consists of endoscopic transluminal drainage (ETD) followed by directed endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy (DEN), has been accepted as the standard treatment for symptomatic WON [

5,

8,

9]. The suitable duration of endoscopic treatment for WON is more than 4 weeks when completely encapsulated by a well-defined wall [

10].

Patients with symptomatic WON without radiology-guided percutaneous drainage or endoscopic or surgical intervention have high mortality rates secondary to infection, sepsis, or organ failure [

11,

12]. ETD followed by DEN for WON has been widely used and has clinical resolution rates comparable to those of surgical necrosectomy; however, ETD followed by DEN is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality rates [

5,

8]. Adjunctive with DEN is associated with higher WON resolution rates (approximately 77% to 96%) and better safety than percutaneous drainage or ETD alone [

13,

14]. Percutaneous drainage in areas that are endoscopically inaccessible also results in improved clinical outcomes [

7,

15]. The PANTER trial demonstrated that the step-up approach involving percutaneous catheter drainage with subsequent minimally invasive surgical necrosectomy was superior to open surgical necrosectomy, which has complication rates ranging from 47% to 72% [

9,

16]. The percutaneous catheter drainage route was preferred over ETD for early necrosis (<4 weeks) caused by WON with incomplete wall encapsulation or endoscopically inaccessible areas [

9]. DEN resulted in the reduction of the overall inflammatory state and lower rates of new-onset multiorgan failure and major complications compared with surgical necrosectomy [

13,

17]. Recently, there has been a change in the trend of WON management, with the endoscopic step-up approach (drainage followed by necrosectomy) being preferred over open surgical necrosectomy because it demonstrates significantly improved clinical resolution and lower morbidity and mortality. The advantages of different types of drainage stents, either plastic stents or lumen-apposing metal (LAM) stents, are not clear; however, LAM stents are associated with fewer procedure-related adverse events [

18]. Gluck et al. reported that combined modality drainage (endoscopic and percutaneous drainage) is associated with a shorter length of hospitalisation and higher rates of complete resolution of WON than standard percutaneous drainage alone (96% vs 80%) [

19]. However, previous retrospective data showed that the endoscopic step-up approach has higher clinical success rates than combined modality drainage (86% and 58%, respectively) [

15]. This study included patients with symptomatic WON who had undergone the endoscopic step-up approach for necrosectomy with or without adjunctive radiology-guided percutaneous drainage. During this retrospective study, we compared WON resolution, including clinical success, clinical resolution, radiologic resolution, adverse events, number of necrosectomy sessions, achieved with the endoscopic step-up approach alone and the endoscopic step-up approach with radiology-guided percutaneous drainage.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, single-center cohort study enrolled patients with symptomatic WON admitted to the Songklanagarind Hospital who underwent ETD followed by DEN with or without radiology-guided drainage between January 2013 and June 2021. Specifically, all procedures were performed at the Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, which is the only tertiary university hospital in Southern Thailand. Using the hospital’s electronic database, we collected patient data, including baseline characteristics, computed tomography (CT) scan results, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) procedure.

The diagnosis of acute severe (necrotising) pancreatitis and WON were revealed by abdominal radiology. The severity of acute pancreatitis was verified using the CT severity index (CTSI).

The routine practice of our center is to treat symptomatic WON using a minimally invasive approach. The attending physicians (gastroenterologist, internist, and surgeon) referred symptomatic WON patients for ETD and DEN with or without adjunctive percutaneous drainage according to clinical conditions, timing after pancreatitis, encapsulation of WON, and location of the collections with the approval of the authorised physician.

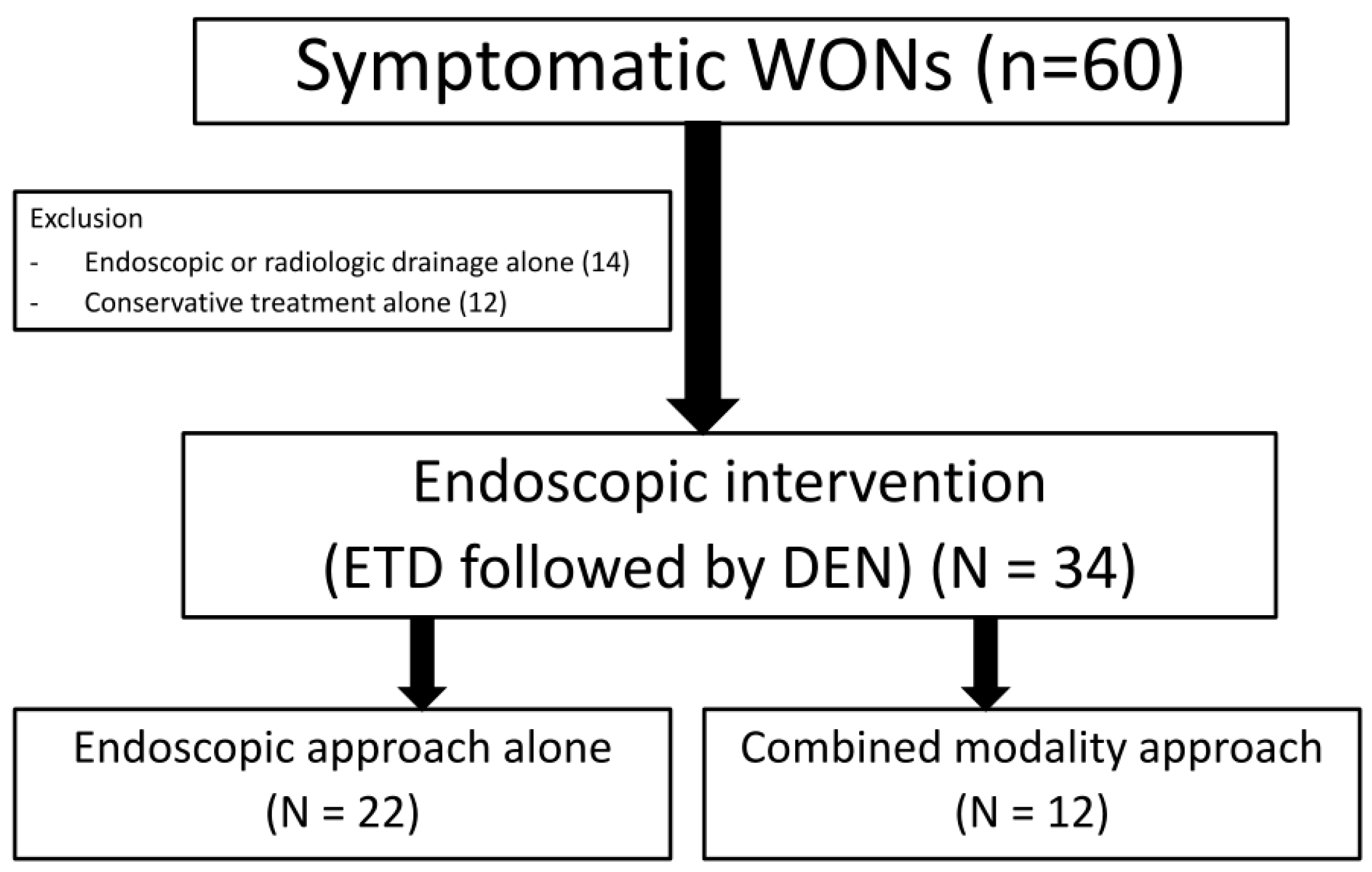

The inclusion criteria were as follows: evidence of symptomatic completely encapsulated WON; abdominal pain, infection, sepsis, and inability to eat; evidence of WON secondary to acute pancreatitis according to CT scan or MRI imaging; age older than 18 years; and able to undergo ETD by EUS-guided drainage. Patients who were unable to undergo ETD and DEN and those with uncorrectable coagulopathy were excluded. The disease severity and local complications were determined according to the CTSI and the criteria of the revised Atlanta classification 2012 [

1,

2]. The consort diagram of the study was illustrated in

Figure 1.

Study Definitions

Technical success was defined as the successful deployment of the LAMs or at least one double pigtail plastic stent (DPPS) between the intestinal wall and WON. For the purposes of this study, only WON patients who achieved successful deployment followed with DEN were included in the analysis. Clinical resolution was defined as improvement in the sign and symptoms of SIRs, sepsis, abdominal pain, and intolerance to eating after the intervention. Clinical success was considered a successful ETD and DEN, defined as a decrease in the size of the WON to < 3 cm on cross-sectional imaging, with resolution of symptoms within 6-months of follow-up [

20].

Endoscopic Transmural Drainage

EUS was performed using a linear array echoendoscope (GF-UCT/P-180 series; Olympus Medical System, Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and ultrasound machine (model SSD alpha 10; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan). Before the procedure, the indications for drainage and abdominal cross-sectional imaging were reviewed, and WON was identified by EUS. The decision to perform EUS-guided drainage and stent type were determined at the discretion of the endoscopist and based on the location of the puncture fistula tract, needle size, and stent type (plastic stent or LAM stent). The optimal location of transmural drainage (ETD) using the transgastric or transduodenal approach was chosen under EUS and Doppler guidance to ensure a minimal distance between WON and the intestinal wall and avoid blood vessels. The puncture was performed with a 19-gauge needle (Echotip; COOK Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). After identifying the proper position of the tip of the needle in WON using EUS, the stylet was removed. Thereafter, the collection was aspirated, and the fluid was subjected to bacterial gram staining and culture testing. The 0.025-inch guidewire was coiled into the collection under EUS guidance, and the access site was dilated using a cautery method with a 6-Fr cystotome followed by a 6-mm hurricane balloon dilator using the noncautery method. One or two 7-Fr double pigtail stents with a length of 5 cm were inserted into WON or LAM stents (stent size 10 x 30 mm; Nagi; Teawong, Korea) were placed between the gastroduodenal lumen and the collection.

Percutaneous Drainage

The radiologically (ultrasound-guided or CT-guided) placed drainage catheters were positioned within the necrotic fluid collections while attempting to avoid pulmonary, hepatic, colonic, and vascular structures. Thereafter, the aspirated fluid was subjected to bacterial gram staining and culture testing, and a 12-Fr to 15-Fr catheter was placed into the collection to perform drainage. After aspiration of as much fluid as possible, the drainage catheters were subjected to gravity and irrigated with 10 to 20 mL of sterile saline three times daily. Percutaneous catheters were sequentially up-sized to a maximum of 18 Fr. Tube dysfunction or occlusion resulted in exchanges that were often preceded by a CT scan of the abdomen.

Directed Endoscopic Transmural Necrosectomy

Endoscopic necrosectomy aims to remove the tissue debris and infected material and multiple open dead spaces that contain infected material. The procedure was performed under conscious sedation by an experienced endoscopist using a gastroscope (EVIS EXERA III, GIF-1TH190; Olympus Medical System, Corp., Tokyo, Japan)

The DEN procedure could be performed after ETD as a step-up approach in the case of a failed clinical response. The optimal timing of endoscopic necrosectomy ranges from 48 to 72 hours after the drainage procedure. The technique of necrosectomy includes mechanical removal using a snare, basket, or tripod retriever and intermittent saline irrigation, followed by 200 mL diluted hydrogen peroxide (1:1) at the end of procedure. DEN was repeated for mechanical removal as much as possible until pink granulation tissue was demonstrated in the wall of the collection.

At our centre, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with pancreatic duct stent placement is not a routine practice. This procedure is performed in the setting of a pancreatic fistula, unresolved or delayed collection over time, pancreatic stricture, and evidence of disconnected duct syndrome. Additionally, the multiple transmural gateway technique (MTGT) approach is not a routine practice because placement of the LAM stent has become first-line deployment at our centre.

Data Collection

We collected the following demographic and clinical characteristics: age, sex, cause of pancreatitis, initial laboratory data, disease severity and local complications according to the CTSI and revised Atlanta classification 2012, EUS procedure data, radiology-guided drainage procedure data, stent types, clinical and radiologic resolution, and hospital stay.

Statistical Analysis

Patient baseline characteristics (demographic, clinical, and laboratory data) of the two groups were compared using the Wilcoxon test for non-normally distributed data and Student’s t-test for normally distributed data. The categorical data were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R program version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

We included 34 consecutive patients (21 males; mean age, 58.4 ± 12 years), including 22 patients in the endoscopic drainage group and 12 patients in the combined modality drainage (CMD) group. Age, sex, body mass index, etiology of pancreatitis, disease severity, comorbid disease, and baseline basic laboratory test results were not significantly different between groups.

Table 1 summarises the background characteristics of each group. The endoscopic approach group had slightly higher body weight; however, the combined modality drainage group had slightly higher rates of multiorgan dysfunction.

The severity of acute pancreatitis according to the CTSI and revised Atlanta classification was equally high in both groups. WON was mostly located centrally and near the stomach, and the mean WON size was 14 cm in each group (no significant difference) are shown in

Table 2. The most frequent symptoms of WON were infection, abdominal pain, and gastric outlet obstruction. As expected, the imaging findings showed that the collection in the left paracolic gutter occurred more often in the CMD group than in the endoscopic approach group.

The EUS-guided drainage procedure was initially evaluated by the endoscopist to determine the optimal location of the access tract. Endoscopic drainage after onset of pancreatitis was performed after a mean of 38 days using the endoscopic approach and after a mean of 42.5 days in the CMD group. The average time to necrosectomy after drainage was 8 days in both groups. The endoscopic procedure, procedure time, and adverse events are shown in

Table 3. All patients underwent the transgastric approach to endoscopic drainage. LAM stents were used for drainage in approximately 80% of this cohort. Surprisingly, the mean number of necrosectomy procedures was equal in both groups (average, 3.5 times in each group). This procedure is usually performed at our center with additional hydrogen peroxide for chemical debridement, and it accounts for 80% of combined mechanical debridement procedures. The mean total necrosectomy time was higher in the CMD group (approximately 118 minutes) than in the endoscopic approach group (78 minutes; p < 0.001). Additionally, minor complications of ETD and DEN occurred equally in both groups, such as bleeding or perforation; they were treated with endoscopic and conservative treatment.

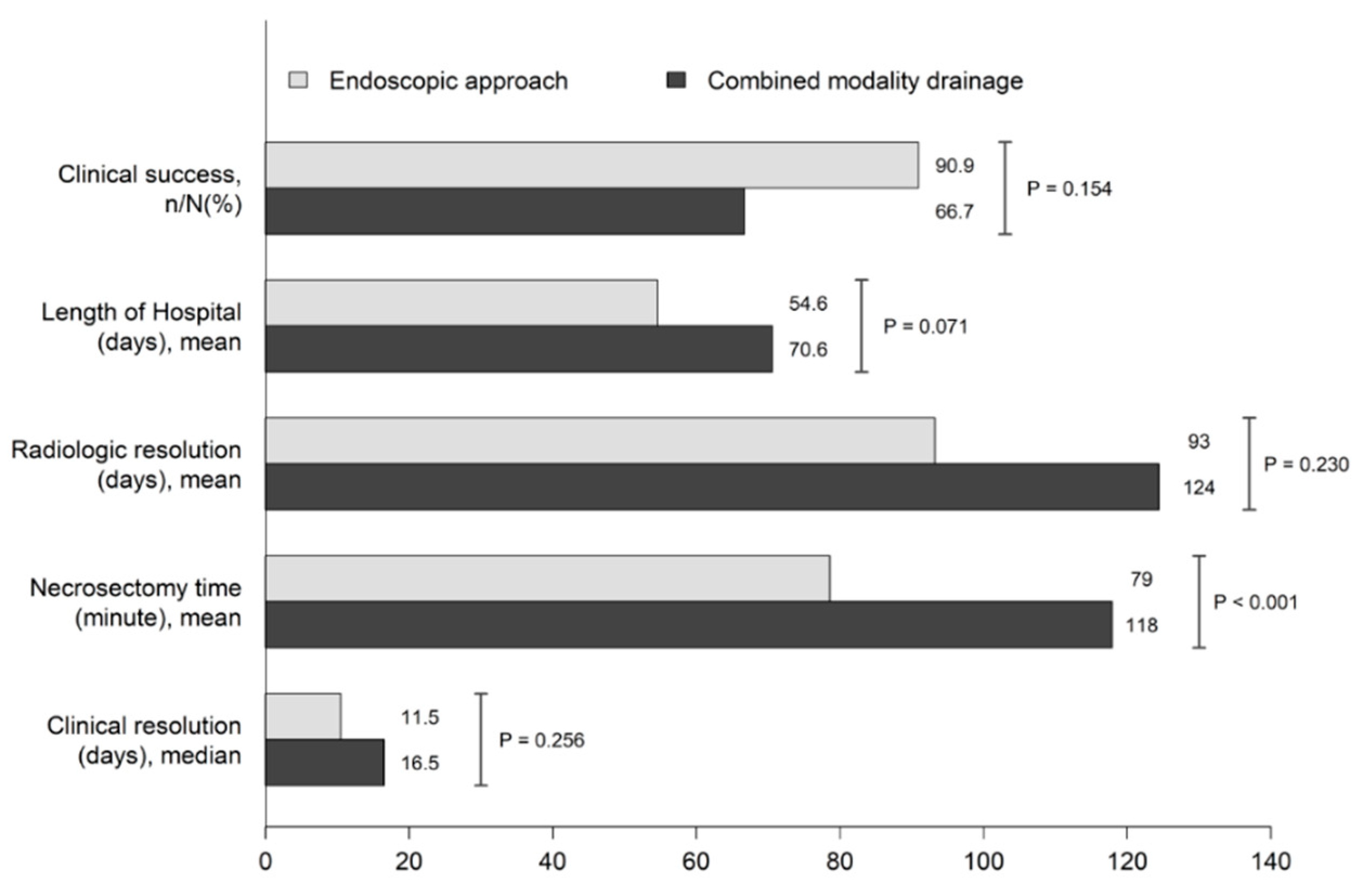

All included symptomatic WON cases clinically resolved after drainage. Clinical success, radiologic resolution, and length of hospital stays are shown in

Figure 2. After treatment with the endoscopic approach and combined modality approach, clinical success and symptoms resolution was achieved in 90.9% of patients within 11.5 days, and 66.7% of patients within 16.5 days, respectively. Furthermore, the time to complete radiologic resolution was shorter in the endoscopic approach group (93 days) than in the combined modality drainage group (124 days). Additionally, the total length of the hospital stay was higher in the combined modality drainage group (70 days) than in the endoscopic approach group (54 days; p= 0.071). The mean duration of stent indwelling in this cohort was 73.5 days.

4. Discussion

Infected WON is a life-threatening condition. The main treatment to improve overall survival is optimal drainage with or without necrosectomy. Endoscopic and radiologic drainage were less invasive than surgical necrosectomy and are the current standard minimally invasive endoscopic modalities [

21]. The endoscopic step-up approach has been designed so that ETD followed by DEN can be performed if needed, allowing clinical success rates that range between 75-90% [

22]. This procedure can achieve complete clinical and radiologic resolution with lower mortality rates (risk ratio 0.27; 95% CI 0.08 – 0.88; p= 0.03) [

23].

In this study, we evaluated the clinical outcomes of the endoscopic approach and compared them with the outcomes of the CMD approach for symptomatic WON. The baseline characteristics of the endoscopic approach and CMD approach groups were similar. Interestingly, this study included pancreatitis patients with a greater severity grade according to the CTSI (median, 9-10) compared to other studies (median, 7-8) [

15,

19,

24]. The mean size of WON was 14 cm and located centrally, which is slightly larger than that reported previously [

15,

25]. As expected, the CMD group had a significantly higher incidence of left paracolic gutter collection, which required another modality for adequate drainage, such as a percutaneous approach.

The ETD procedure was started in cases where the WON was well encapsulated, after which DEN was performed a median of 1 week after drainage. The ETD procedure in our study used NAGI stents for approximately 80% of the cohort. This cohort did not include patients with percutaneous drainage alone. Previous studies showed that clinically successful percutaneous drainage for symptomatic WON was achieved in only 35% to 51% of cases [

8,

16]. The endoscopic step-up approach achieves more successful resolution (88% vs 45%; p=0.03) and shorter hospital stays (15 days vs. 38 days p=0.448) compared with standard endoscopic drainage alone or percutaneous drainage alone [

19,

26]. A previous study showed that LAM stents were superior to plastic stents in terms of overall treatment efficacy and number of endoscopy sessions (2.2 vs 3.6; p=0.04) [

20,

25,

27]. The larger lumen diameter stents allow adequate drainage and prevent occlusion and subsequent infection, which were strengths of LAM over DPPS.

The endoscopic necrosectomy procedure was performed an average of 3.5 times in both groups; however, the total necrosectomy procedure time of each session was significantly higher in the CMD group (118 minutes) than in the endoscopic approach group (78 minutes). These findings may be explained by the complex extension and deep penetrating route of the collection in the CMD group, especially in left and right paracolic gutters, which might be more difficult to treat using the endoscopic approach alone and more time-consuming than non-complex WON.

All patients achieved clinical resolution after the procedures. The endoscopic approach resulted in earlier clinical resolution, within 11 days, compared to the CMD group in 16 days. Interestingly, the endoscopic approach also achieved higher clinical success rates at 90.9% than the CMD approach at 66.7%. Siddiqui et al. reported the ETD followed by DEN with LAM allowed high endoscopic therapy success 88.2% [

28]. Furthermore, the total hospital stay was shorter for the endoscopic approach group. Surprisingly, this finding was the same as that reported by Nemato et al., who found that the endoscopic approach was associated with a reduced hospital stay of approximately 17 days, and that the dual modality approach was associated with a hospital stay of approximately 31 days [

15]. Our outcomes for clinical success, clinical resolution, and total hospital stay were superior in the endoscopic approach. This might be attributed to the fact that the endoscopic approach group had only centrally located WON (non-complex WON), which might be easier to drain and DEN than cases of complex WON located in areas that are inaccessible to an endoscopic approach. The large lumen patency of the stent (LAM) in this cohort might be beneficial effect for adequate drainage and clinical outcomes. Additionally, the H2O2 assisted DEN demonstrated approximately 80% of case, which could be achieved satisfactory results, the previous meta-analysis showed the H2O2 assisted DEM achieved high clinical success 91.6% (95% CI 86.1-95) and no adverse event attributable to H2O2 were reported [

29].

Interestingly, percutaneous drainage was performed between 20 and 67 days (mean, 41.5 days) after the onset of pancreatitis; this treatment comprised early percutaneous drainage and adjunctive percutaneous drainage. In theory, the advantage of the CMD is the shorter duration of percutaneous catheter drainage indwelling because of ETD providing better luminal exit for pancreatic secretions than percutaneous drainage alone [

24].

Although patients in the CMD group had less severe disease than the endoscopic approach group according to the initial CTSI, they had a larger collection in the right and left paracolic gutters than patients in the endoscopy group. Radiologic drainage is indicated for cases of early sepsis that do not respond to medication and cases of gas formation in the collection. Additional drainage is indicated when the area is endoscopically inaccessible. Conservative treatment with intravenous antibiotics is the main treatment for incomplete encapsulation. However, Trikudanathan et al. reported that the endoscopic step-up approach in early WON (< 4 weeks) with strong indication for drainage did not increase procedure related complications [

10,

30]. Radiology-guided catheter drainage uses a single catheter for approximately 83% of cases. The majority concern percutaneous drainage was external pancreatic fistula (EPF), Rana SS, et al. showed the incidence of EPF was significant higher in the percutaneous drainage (21.95% vs 0%, p = 0.021) compare with ETD [

31]. Percutaneous necrosectomy was necessary for only one patient; for that patient, a 28-Fr catheter was placed via the intercostal chest to perform drainage, followed by an 8.8-mm-diameter gastroscope for mechanical necrosectomy. Moyer et al. reported that percutaneous flexible endoscopic necrosectomy for WON that was not amenable to transluminal drainage resulted in successful percutaneous drainage and clinical resolution for 22 of 23 patients [

7].

Complications such as perforation and bleeding were not significant in both groups. Stent-related complications, including delayed bleeding and buried LAM stent syndrome did not occur during this study; however, the stent indwelling time (73 days) was longer than that observed in previous studies [

32]. Interestingly, pancreatocutaneous fistula formation and disease related death did not occur during this study.

Limitations

This study represents the real-world situation of symptomatic WON patients in developing countries, where patients usually present late during the course of disease with abdominal pain and a large collection. Few factors that may have caused the selection bias and affected the results of this study include the fact that the CMD group had higher initial severity conditions, such as early sepsis, than the endoscopic approach group, who could not wait for well-encapsulated WON to occur and required early radiologic drainage. Another factor was the additional indication for late percutaneous drainage because of the extension of the collection to the paracolic gutter (an endoscopically inaccessible area). Additionally, this study used a retrospective design, and some differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients in the endoscopic approach and the CMD groups existed; however, the differences in the baseline laboratory data were not associated with the outcomes of our study. The strength of this study is that it reflects a real-world practice in a limited-resource country. Moreover, the protocols for the procedure (ETD and DEN), follow-up, clinical condition, and imaging after clinical resolution were consistent. Therefore, the data and follow-up were accurate and complete.

5. Conclusions

The endoscopic step-up approach resulted in the clinical resolution of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis comparable to that of the endoscopic approach with adjunctive percutaneous drainage. However, the endoscopic approach allows a higher clinical success, early clinical and radiologic resolution, along with a shorter hospital stay.

Author Contributions

T.P. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data collection, as well as manuscript writing. T.P., T.C., T.W. and N.N. made contributions to the design of the study, data analysis, and manuscript writing. T.P., N.N., B.O. and T.Y. performed and completely reported endoscopic EUS-guided drainage data. T.T. and P.B. contributed to the abdominal cross-sectional imaging. P.S. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and approval of English language. T.P. is the first author and corresponding author responsible for ensuring that all listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (approval number: REC 64-301-21-1).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Medicine at Prince of Songkla University for providing resources and aiding data collection in the study. We also thank all the participating patients and hope this work will be beneficial for clinical practice in the future.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Banks, P.A.; Freeman, M.L. Practice guideline in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006, 101, 2379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, B.R.; Jensen, K.K.; Bakis, G.; Shaaban, A.M.; Coakley, F.V. Revised Atlanta classification for acute pancreatitis: A pictorial essay. Radiographics 2016, 36, 367–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.; et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis – 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2013, 13, e1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.Y.; Arnoletti, J.Y.; Holt, J.P.; Sutton, B.; Hasan, M.K.; Navaneethan, U.; et al. An endoscopic transluminal approach, compared with minimally invasive surgery, reduces complications and costs for patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1027–40.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Gao, S.L.; Liang, Z.Y.; Yu, W.Q.; Liang, T.B. Successful resolution of gastric outlet obstruction caused by pancreatic pseudocyst or walled-off necrosis after acute pancreatitis: the role of percutaneous catheter drainage. Pancreas 2015, 44, 1290–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, M.T.; Walsh, L.T.; Manzo, C.E.; Loloi, J.; Burdette, A.; Mathew, A. Percutaneous debridement and washout of walled-off abdominal abscess and necrosis by the use of flexible endoscopy: an attractive clinical option when transluminal approaches are unsafe or not possible. VideoGIE 2019, 4, 389–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Brunschot, S.; van Grinsven, J.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 51–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanrarojanasiri, T.; Ratanachu-Ek, T.; Isayama, H. When should we perform endoscopic drainage and necrosectomy for walled-off necrosis? J Clin Med 2020, 9, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikudanathan, G.; Tawfik, P.; Amateau, S.K.; Munigala, S.; Arain, M.; Attam, R.; et al. Early (<4 weeks) versus standard (> 4 weeks) endoscopically centered step-up interventions for necrostizing pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsmark, C.E. Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2022–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, P.A. The role of needle-aspiration bacteriology in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis. In Acute Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Therapy; Editor Bradley E.L. III,. Raven: New York, 1993; pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Conwell, D.L. Thompson C.C. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy versus step-up approach for walled-off pancreatic necrosis; comparison of clinical outcome and health care utilization. Pancreas 2014, 43, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, A.; Taghizadeh, N.; Ishikawa, T.; Gonzalez-Moreno, E.; Bass, S.; Cole, M.J.; et al. Endosonography-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: Comparative outcomes by stent type. Surg Endosc 2021, 35, 2698–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemato, Y.; Attam, R.; Arain, M.A.; Trikudanathan, G.; Mallery, S.; Beilman, G.J.; et al. Interventions for walled off necrosis using an algorithm based endoscopic step-up approach: outcomes in a large cohort of patients. Pancreatology 2017, 17, 663–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Santvoort, H.C.; Besselink, M.G.; Bakker, O.J.; Hofker, H.S; Boermeester, M.A.; Dejong, C.H.; et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2010, 362, 1491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, O.J.; van Santvoort, H.C.; van Brunschot, S.; Geskus, R.B.; Besseling, M.G.; Bollen, T.L.; et al. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis. JAMA 2012, 307, 1053–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.Y.; Navaneethan, U.; Hasan, M.K.; Sutton, B.; Hawes, R.; Varadarajulu, S. Non-superiority of lumen-apposing metal stents over plastic stents for drainage of walled-off necrosis in a randomized trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1200–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluck, M.; Ross, A.; Irani, S.; Lin, O.; Gan, S.I.; Fotoohi, M.; et al. Dual modality drainage for symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis reduces length of hospitalization, radiological procedures, and number of endoscopies compared to standard percutaneous drainage. J Gastrointest Surg 2012, 16, 248–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkolfakis, P.; Petrone, M.C.; Tadic, M.; Tziatzios, G.; Karoumpalis, I.; Francesco, S. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: a retrospective multicentre European study. Ann Gastroenterol 2022, 35, 654–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxhoorn, L.; Fockens, P.; Besselink, M.G.; Bruno, M.J.; van Hooft, J.E.; Verdonk, R.C.; et al. Endoscopic management of infected necrotizing pancreatitis: an evidence-based approach. Curr Treat Options Gastro 2018, 16, 333–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, S. Comparison between lumen-apposing metal stents and plastic stents in endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collection: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pancreas 2021, 50, 571–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Brunschot, S.; Hollemans, R.A.; Bakker, O.J.; Beeseling, M.G.; Baron, T.H.; Beger, H.G.; et al. Minimally invasive and endoscopic versus open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis: a pooled analysis of individual data for 1980 patients. Gut 2017, 67, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluck, M.; Ross, A.; Irani, S.; Lin, O.; Hauptmann, E.; Siegal, J.; et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis reduced hospital stay and radiologic resources. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010, 8, 1083–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Kowalski, T.E.; Loren, D.E.; Khalid, A.; Soomro, A.; Mazhar, S.M.; et al. Fully coverd self-expanding metal stents versus lumen-apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stent versus plastic stents for endoscopic drainage of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: clinical outcomes and success. Gastrointest Endosc 2017, 85, 758–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, T.B.; Chahal, P.; Papachristou, G.I.; Vege, S.S.; Petersen, B.T.; Gostout, C.J.; et al. A comparison of direct endoscopic necrosectomy with transmural endoscopic drainage for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc 2009, 69, 1085–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2018, 28, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.A, Adler, D.G., Nieto, J., Shah, J.N., Binmoeller, K.F., Kane, S., et al. EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis by using a novel lumen-apposing stent: a large retrospective, multicentre U.S. experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016, 83, 699-707. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.P., Madhu, D., Toy, G., Chandan, S., Khan, S.R., Kassab, L.L., et al. Hydrogen peroxide-assisted endoscopic necrosectomy of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2022, 95, 1060-6.e7. [CrossRef]

- Oblizajek, N.; Takahashi, N.; Agayeva, S.; Bazerbachi, F.; Chandrasekhara, V.; Levy, M.; et al. Outcomes of early endoscopic intervention for pancreatic necrosis collections: a matched case-control study. Gastrointest Endosc 2020, 91, 1303–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.S., Verma, S., Kang, M., Gorsi, U., Sharma, R., Gupta, R. Comparison of endoscopic versus percutaneous drainage of symptomatic pancreatic necrosis in the early (< 4 weeks) phase of illness. Endosc Ultrasound 2020, 9, 402-9. [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.S.; Young, J.Y.; Jirapinyo, P. Comparative study evaluating lumen apposing metal stents versus double pigtail plastic stents for treatment of walled-off necrosis. Pancreas 2020, 49, 236–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).