Introduction

Gingival enlargement or gingival hyperplasia is a gingival disease which involves an increase in the size of the gingiva. Gingival enlargement is a multifactorial disease and is often attributed to several etiological factors such as plaque, pregnancy, drug-induced, systemic hormonal imbalances, leukemias, thrombocytopenia, blood dyscrasias and idiopathic gingival fibromatosis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Recently, an association between orthodontic therapy and gingival enlargement has been identified [

7]. This has been linked to various reasons like the incapability to maintain good oral hygiene due to the presence of the orthodontic brackets and wires, plaque retention due to poor oral hygiene, prolonged orthodontic therapy and allergy to the nickel in the orthodontic wires or appliances [

8].

The frequency of the occurrence of nickel allergy is 1-2% in males and 10% in females [

9,

10,

11]. In order to elicit an allergen response from nickel in the mucosal tissues, the concentration of nickel should be 5-12 times higher than the nickel allergy produced in contact with the skin structure [

12]. The primary component of the elastic Nitinol arch wires employed for the initial tooth aligning phase is nickel with a concentration of 47-50% [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Depending upon its concentration, the mechanism behind the epithelial proliferation in response to the nickel may probably be the initiation of the amalgamation of the inflammatory cytokines and the up modulation of the keratinocyte growth factor expression in keratinocytes [

17]. The nickel allergy usually manifests as a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction and is mediated via the T-cells and occurs in two phases [

18].The first phase is an initial sensitization phase in which no response is produced upon contact. However, in the second phase, a delayed hypersensitivity reaction is triggered which may produce clinical signs and symptoms within a couple of days or rarely up to two weeks [

19].

After a diagnosis is made, and if there is an absence of any symptoms, then generally no treatment is required. However, these Nitinol wires can be replaced by low concentration nickel-stainless steel wires. The patient can then be re-evaluated and if the condition persists, surgical intervention may be required [

20].

There are a very limited number of documented cases on Nickel allergy induced gingival enlargement probably because of the difficulty in diagnosing these cases and the unknown pathogenicity involved. The aim of this paper was to enable the clinician to recognize and arrive at a definitive solution in order to treat these cases.

Case report

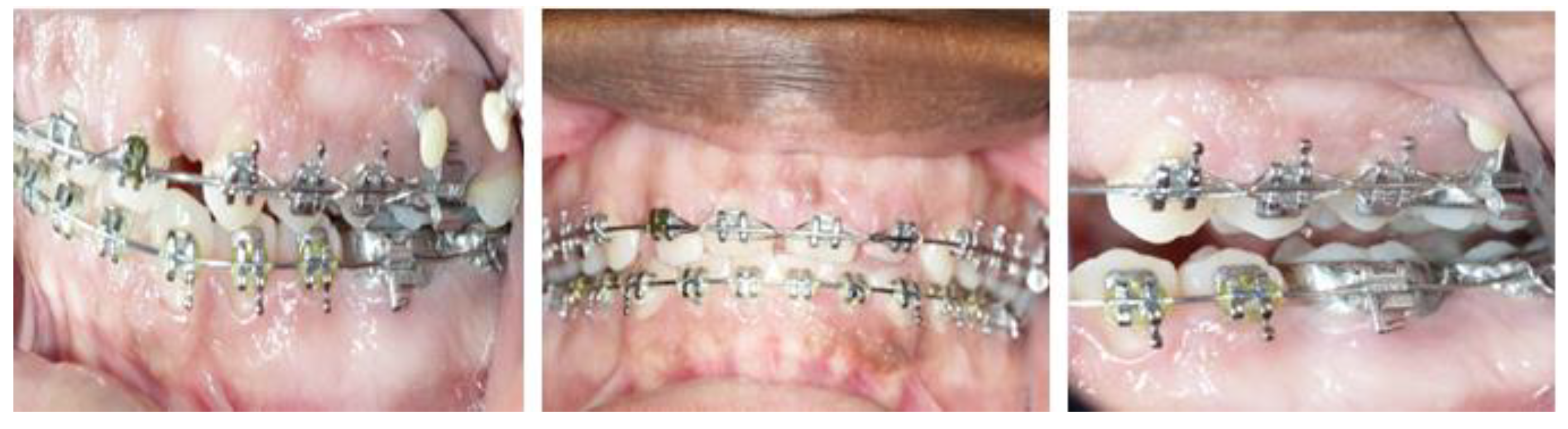

A 34 year old Afro-American female undergoing fixed orthodontic therapy had presented with a chief complaint of swollen gums (

Figure 1&2). The patient mentioned that she first noticed the enlargement a week after the Nitinol wires were placed. Upon clinical examination, it was noted that the gingiva, particularly in the maxillary anterior region was inflammatory and enlarged in size (

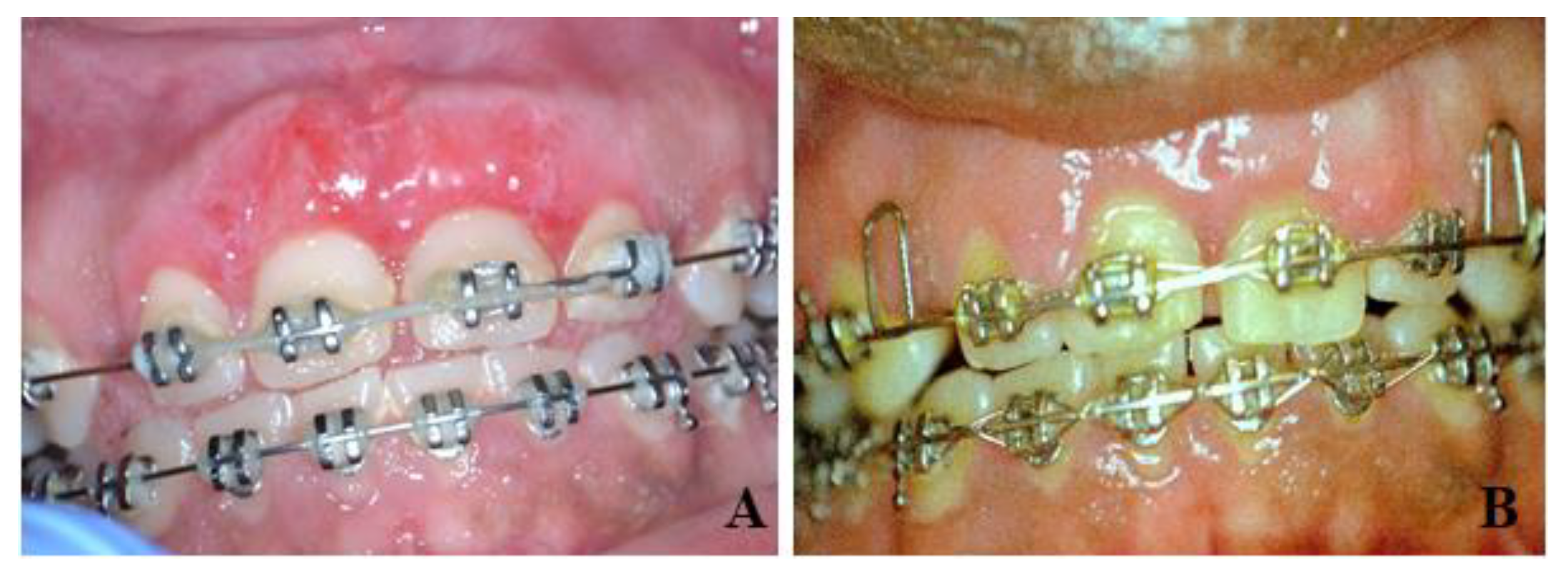

Figure 3). Bleeding on probing was also noted at several sites. The gingiva was fibrotic in consistency. The pocket depths of tooth no 7, 8, 9 and 10 was 7mm. However, the increase in pocket depths was due to the gingival enlargement and not due to the clinical attachment loss levels. Panoramic radiographs and full mouth intra oral radiographs were obtained to determine if any bone loss was present and complete blood examination was performed in order to rule out the differential diagnosis. The patient was also not on any medication and was not pregnant at that time. Finally, a diagnosis of nickel wire-induced gingival enlargement was made after ruling out all the possible etiological factors. The preliminary treatment plan involved performing an oral prophylaxis procedure to eliminate the plaque accumulation and the Orthodontist was advised to replace the Nitinol wires with stainless-steel wires. After the wires were replaced, the patient was re-evaluated after six weeks. At six weeks, there was a decrease in the inflammation of the gingiva and a significant reduction in the bleeding on probing at various sites. However, the decrease in the size of the gingiva was not adequate enough to be ignored. And hence, a treatment plan involving surgical intervention for the maxillary anteriors was drafted. Prior to the surgery, the patient was informed about the need for an additional surgery post commencement of the orthodontic therapy due to tissue rebound. After the informed consent was obtained, 2% xylocaine (1:100,000 epinephrine) was injected into the maxillary anterior region. Owing to the fibrotic consistency of the gingiva, it was predetermined that a gingivectomy was required to eliminate the excessive tissue. Using a 15C blade, the gingiva was scraped in an apical to coronal direction until the desired aesthetic outcome was achieved. 0.12% Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash was prescribed for the patient along with an analgesic for the post-operative pain relief (

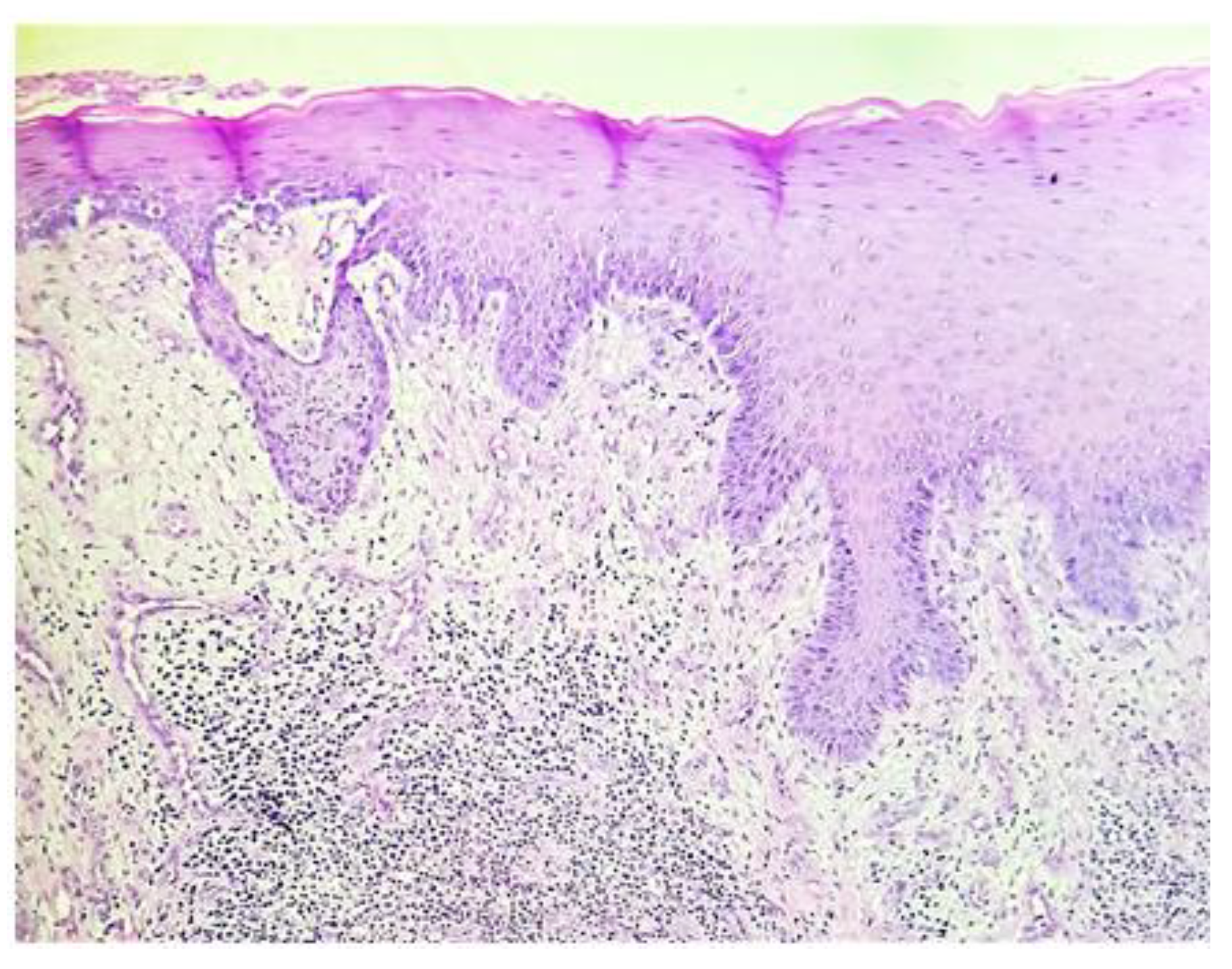

Figure 4). The excised specimen was sent for the histopathological evaluation. Histopathological examination revealed a hyperplastic parakeratinized epithelium overlying inflamed connective tissue. The underlying connective tissue showed numerous proliferating young fibroblasts admixed with aggregates of dense chronic inflammatory cells, budding capillaries were seen at few places. A histopathological diagnosis suggestive of inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia was given (

Figure 5). The patient was followed up after a week and was on a three month recall and was thereafter followed until a year and the gingiva showed no signs of re-enlargement (

Figure 6).

Discussion

Patients who undergo orthodontic treatment generally display several oral clinical manifestations such as sensitivity, increased caries risk, and gingival enlargement. However, gingival enlargement associated with orthodontic treatment generally begins as a plaque associated gingivitis due to the inability to maintain good oral hygiene, ultimately leading to an enlargement of the gingiva owing to the inflammation which is triggered by the corrosion of the orthodontic appliances and wires. The primary component of orthodontic wires is nickel and hence this condition is known as nickel allergy induced gingival enlargement. Gursoy et al [

17] reported that gingival enlargement associated with allergy depicts fragile gingiva with marginal gingival redness along with a histological description of an increase in epithelial thickness in conjunction with a significant increase in epithelial cell proliferation in response to low-dose nickel concentrations. On the other hand, Plaque induced gingival enlargement demonstrates a fibrous or thickened gingiva.

In this case, after rejecting the possible causative factors, a provisional diagnosis of nickel wire allergy induced gingival enlargement was arrived upon. The patient denied any previous allergic history and refused to undergo a patch(cutaneous sensitivity) test [

21]. The patch test is one of the most reliant diagnostic methods in order to affirm a nickel allergy. The amount of plaque present was too minimal in order to attribute the enlargement to it. Hence, a decision to have the Ni-Ti (Nickel Titanium) wire replaced with a stainless steel was decided upon. The immediate resolution of the inflammation, which was suggestive of an allergic contact mucositis reaction and the decrease in the size of the gingiva post replacement of the wire confirmed our diagnosis with histpathological evaluation.

Nickel from the wires is leached into the plaque and saliva of the patients[

22]. However, it has been reported that a concentration of 50% nickel in wires does not produce any cytotoxic reached when leached. Low dose nickel acts by increasing the cellular proliferation thus leading to the gingiva hyperplasia [

23]. In orthodontic treatment, austenitic stainless steel that contains 18% chromium and 8% nickel is often used. This material is known as the material most frequently causes hypersensitivity. The concentration of nickel in stainless steel wires is approximately 15%. Other alternatives include the use of fiber-reinforced composite archwires. Additionally, wires such as TMA (Titanium-Molybdenum alloy), pure titanium, and gold-plated wires may also be used without risk. Ion-implanted nickel-titanium arch wires are corrosion resistant due to a non-crystalline surface layer, thus decreasing the risk of an allergic response [

20,

24]. Moreover, it has been stated that hypersensitivity towards nickel shows greater predilection in females particularly because of their exposure to allergen or materials triggering hypersensitive, e.g. jewelry, more often.

Orthodontic treatment–induced gingival hyperplasia depicts a typical fibrous and reddened appearance of the gingiva, which is seen in inflammatory gingival lesions [

25]. Fibrous gingival enlargements associated with fixed orthodontic appliances are determined to be transitory Several studies have stated that upon removal of the wires, there is a complete resolution of the hyperplasia and generally no surgical intervention is required. However, studies by Ramadan suggested the need for a surgical intervention which was in accordance with our case [

26].When inflammatory gingival enlargements involve a fibrotic component that does not resolve completely, surgical removal is the treatment of choice. Depending on the amount of bone loss, the surgical treatment may either involve the need for performing a gingivectomy or an aesthetic crown lengthening procedure. There is only 1 reported case in literature to the best of our knowledge, by Counts et al [

27]and ours is the second case (

Table 1). As per zigante M et al (2022), the gingiva of patients with metal allergic sensitisation had a stronger degree of inflammation, a milder degree of fibrosis, mild hyperplasia and colliquation of the basal layer, exocytosis, and band-like inflammatory infiltrates compared to that of non-sensitised patients. [

28,

29]

Conclusion

This report helps to highlight the significance of patient compliance in treatment planning. The patient should be made aware of the allergy at the initial visit and oral hygiene instructions should be reinforced at every visit. The importance of a regular periodontal maintenance and patient compliance is important in the success of these cases.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding.

Abbreviations

Ni-Ti: Nickel Titanium; TMA: Titanium-Molybdenum alloy

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The patient gave her consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr Robert Cohen and Dr Michael Levine for their assistance with this case as well as the Department of Orthodontics and Oral Diagnostic sciences for the co-operation.

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no competing interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- Lv, Z., H. Yao, and G. Zhuang, A rare case of idiopathic multiple hyperplasia of inflammatory granulation in the oral cavity. Quintessence Int, 2014. 45(2): p. 109-13. [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, M.L., D. Bencivenni, and R.E. Cohen, Drug-induced gingival enlargement: an overview. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2013. 34(5): p. 330-6.

- McLeod, D.E., et al., Severe postpartum gingival enlargement. J Periodontol, 2009. 80(8): p. 1365-9. [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, J.A., et al., Severe phenytoin-induced gingival enlargement associated with periodontitis. Gen Dent, 2008. 56(2): p. 199-203; quiz 204-5, 224.

- Anil, S., et al., Gingival enlargement as a diagnostic indicator in leukaemia. Case report. Aust Dent J, 1996. 41(4): p. 235-7. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, H., Y. Kameyama, and I. Ishikawa, Unusual gingival enlargement with rapidly progressive periodontitis. Report of a case. J Periodontol, 1993. 64(10): p. 1008-12. [CrossRef]

- Kouraki, E., et al., Gingival enlargement and resolution during and after orthodontic treatment. N Y State Dent J, 2005. 71(4): p. 34-7.

- Kloehn, J.S. and J.S. Pfeifer, The effect of orthodontic treatment on the periodontium. Angle Orthod, 1974. 44(2): p. 127-34. [CrossRef]

- Meding, B., Epidemiology of nickel allergy. J Environ Monit, 2003. 5(2): p. 188-9. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, N.B., et al., Nickel contact hypersensitivity in children. Pediatr Dermatol, 2002. 19(2): p. 110-3. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, H., et al., Epidemiology of nickel allergy. Contact Dermatitis, 1987. 16(3): p. 122-8. [CrossRef]

- Mehulic, M., et al., Expression of contact allergy in undergoing prosthodontic therapy patients with oral diseases. Minerva Stomatol, 2005. 54(5): p. 303-9.

- Andreasen, G., A clinical trial of alignment of teeth using a 0.019 inch thermal nitinol wire with a transition temperature range between 31 degrees C. and 45 degrees C. Am J Orthod, 1980. 78(5): p. 528-37.

- Domokos, G. and J. Denes, [The Nitinol arch wire]. Fogorv Sz, 1980. 73(5): p. 129-30.

- Rubright, E., Nitinol wires: Serendipity and research. Iowa Dent Bull, 1976. 9(1): p. 13-5.

- Civjan, S., E.F. Huget, and L.B. DeSimon, Potential applications of certain nickel-titanium (nitinol) alloys. J Dent Res, 1975. 54(1): p. 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, U.K., et al., The role of nickel accumulation and epithelial cell proliferation in orthodontic treatment-induced gingival overgrowth. Eur J Orthod, 2007. 29(6): p. 555-8. [CrossRef]

- Pazzini, C.A., et al., Allergy to nickel in orthodontic patients: clinical and histopathologic evaluation. Gen Dent, 2010. 58(1): p. 58-61.

- Kolokitha, O.E. and E. Chatzistavrou, Allergic reactions to nickel-containing orthodontic appliances: clinical signs and treatment alternatives. World J Orthod, 2008. 9(4): p. 399-406.

- Rahilly, G. and N. Price, Nickel allergy and orthodontics. J Orthod, 2003. 30(2): p. 171-4.

- Menne, T., et al., Patch test reactivity to nickel alloys. Contact Dermatitis, 1987. 16(5): p. 255-9. [CrossRef]

- Fors, R. and M. Persson, Nickel in dental plaque and saliva in patients with and without orthodontic appliances. Eur J Orthod, 2006. 28(3): p. 292-7. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.C., et al., An in vitro comparison of nickel and chromium release from brackets. Braz Oral Res, 2009. 23(4): p. 399-406. [CrossRef]

- Vitalyos, G., et al., [Orthodontic treatment possibilities of allergic patients]. Fogorv Sz, 2007. 100(2): p. 71-6.

- Ozkaya, E. and G. Babuna, Two cases with nickel-induced oral mucosal hyperplasia: a rare clinical form of allergic contact stomatitis? Dermatol Online J, 2011. 17(3): p. 12.

- Ramadan, A.A., Effect of nickel and chromium on gingival tissues during orthodontic treatment: a longitudinal study. World J Orthod, 2004. 5(3): p. 230-4; discussion 235.

- Counts, A.L., et al., Nickel allergy associated with a transpalatal arch appliance. J Orofac Orthop, 2002. 63(6): p. 509-15. [CrossRef]

- Zigante, M.; Spalj, S.; Prpic, J.; Pavlic, A.; Katic, V.; Matusan Ilijas, K. Immunohistochemical and Histopathological Features of Persistent Gingival Enlargement in Relation to Metal Allergic Sensitisation during Orthodontic Treatment. Materials 2023, 16, 81. [CrossRef]

- Zigante M, Rincic Mlinaric M, Kastelan M, Perkovic V, Trinajstic Zrinski M, Spalj S. Symptoms of titanium and nickel allergic sensitization in orthodontic treatment. Prog Orthod. 2020 Jul 1;21(1):17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).