1. Introduction

The international crisis of toxic unregulated drug-related morbidity and mortality is well documented[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Regions identified as suffering from significant impacts, such as North America, have produced a growing body of literature that calls attention to the high incidence of drug poisoning-related deaths secondary to the increasingly toxic supply of unregulated drugs[

6]. In the United States, 136 people die daily from opioid-related drug poisoning events[

7], while in British Columbia, Canada, illicit drug toxicity is now the leading cause of unnatural death in the province, responsible for more deaths than suicides, homicides, motor vehicle incidents, drownings, and fire-related deaths combined[

8].

Due to the frequency at which paramedics provide care to people who use drugs (PWUD), and the fact that they deliver care in varying contexts (e.g., in patients’ homes, communities) paramedics may be uniquely positioned to reduce drug-related harm. Previous research has largely focused on the emergency response to drug poisoning events, with less emphasis on the holistic and preventative role of paramedics in reducing drug-related harms. Such lack of emphasis on the holistic role results in patient care delivery that is lifesaving, but not necessarily life-extending. The sharp increase in drug poisoning-related deaths warrants an innovative approach, one that is proactive, and centered around a patient's autonomy over their drug use.

To inform and realize the impact that paramedics can have in caring for PWUD, their role must be better understood and explored. Despite the importance of the relationship between paramedics and PWUD, little literature examines the patient experience of paramedic care and how this influences each encounter.

As such, this scoping review aimed to answer the following research questions:

What is known about paramedics and their role in caring for PWUD?

What current opportunities and gaps exist in the literature regarding the primary research question?

How may the implications of this research inform contemporary and future paramedic practice?

Objective

The objective of this review was to gain an understanding of how the existing body of literature describes the paramedic role in caring for PWUD by discovering themes, and gaps for further recommended areas of research focus[

9]. A scoping review was deemed the most appropriate methodology for satisfying the research questions due to its strategically broad and open-ended nature. This methodology was chosen over a systematic review as specific interventions, or comparisons were not evaluated or conceptualized in the aim of the study.

Population

The population of the study included PWUD. To ensure the full scope of the literature was captured, stigmatizing terms no longer accepted as patient-centric were used in the search strategy (see Appendix 1), this was informed by a suggested list of search terms related to addiction[

10].

Concept

The concept was drug-related substance use, with a focus on illicit substances linked to the global overdose/toxic drug/drug poisoning crisis. Drug-related substances included opioid and non-opioid central nervous system (CNS) depressants and stimulants.

Context

The context was paramedic delivered care. This review encompasses the entire scope of the paramedic role where “paramedic” is representative of the paramedic profession and includes all practice levels and settings.

2. Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with JBI Scoping Review Guidance[

11]. The protocol was created in March 2022 and later registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) (

https://bit.ly/3V32ehD). We reported our process and findings according to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews[

12]. No ethics approval was required for this scoping review as no human participants were involved. A preliminary search of MEDLINE, PROSPERO, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted, and no current or in-progress systematic or scoping reviews on the topic were identified.

Identification of Relevant Studies

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished studies. An initial limited search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to further inform the search strategy keywords. The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was further adapted for each database and/or information source (see appendix 1).

We searched EMBASE via Ovid, CINAHL via EBSCO, and MEDLINE via Ovid in April 2022 with supplemental searches in June 2022. We searched for grey literature by screening the first 1,000 results returned by the search engine Google, as well as the first 1,000 results from Google Scholar[

13,

14].

Study Selection

Peer-reviewed empirical studies of any design as well as grey literature were selected if the study objective or articles’ body discussed the care of PWUD from an out-of-hospital, and paramedic-focused lens. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they pertained specifically to the paramedic's role in caring for PWUD and were published in English since 2002. This limit was set with the aim of appreciating the evolution of the paramedic role by capturing the past two decades and was informed by the literature related to the drug poisoning crisis. Articles were excluded if their primary focus was isolated alcohol use, suicidality, excited delirium, clinical drug efficiency, occupational risks, substance use by paramedics, non-illicit drug poisonings, ethnography of PWUD, or geospatial analyses. Although these areas intersect with the toxic drug crisis in salient ways, they do not inform the research questions posed.

The review process consisted of two levels of screening: (1) a title and abstract review and (2) a full-text review. For the first level of screening, a title/abstract screening form was developed by the primary author (JB) informed by the JBI Scoping Review guidance[

11], using Covidence (Veritas Health, Melbourne, Australia) and reviewed by two co-authors (RA and AB). The screening criteria were tested on a sample of abstracts prior to beginning the abstract review to ensure that they were sensitive enough to capture any articles that may relate to the review question. Conflicts were resolved by discussion with co-authors and criteria were refined until agreement was reached.

In the second step, four of the authors (JB, MOT, ML, and RA) independently assessed the full texts of screened articles in duplicate to determine if they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Data Charting

Data were extracted by at least one reviewer (JB, MOT, ML, or RA), using a data extraction form created by the primary researcher (JB), informed by the JBI Scoping review guidance[

11] (see Appendix 2). Informed by restricted review methodology[

15], a 20% quality check was then completed by the most experienced reviewer (AB) who did not partake in the data extraction stage. Data extracted included article title, author name and year of publication, country of study, study aim/objective, study design, key findings in the study results, discussion, conclusions about the paramedic role, and iterative categorization. The extracted data were exported from Covidence into Excel 365 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) for collation, analysis, and synthesis.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

Extracted data were organized and used to report on the included articles' findings. Descriptive statistics were used for quantitative data analysis, and an analysis of study characteristics was used to explore and report qualitative data[

16].

3. Results

Identification of Potential Studies

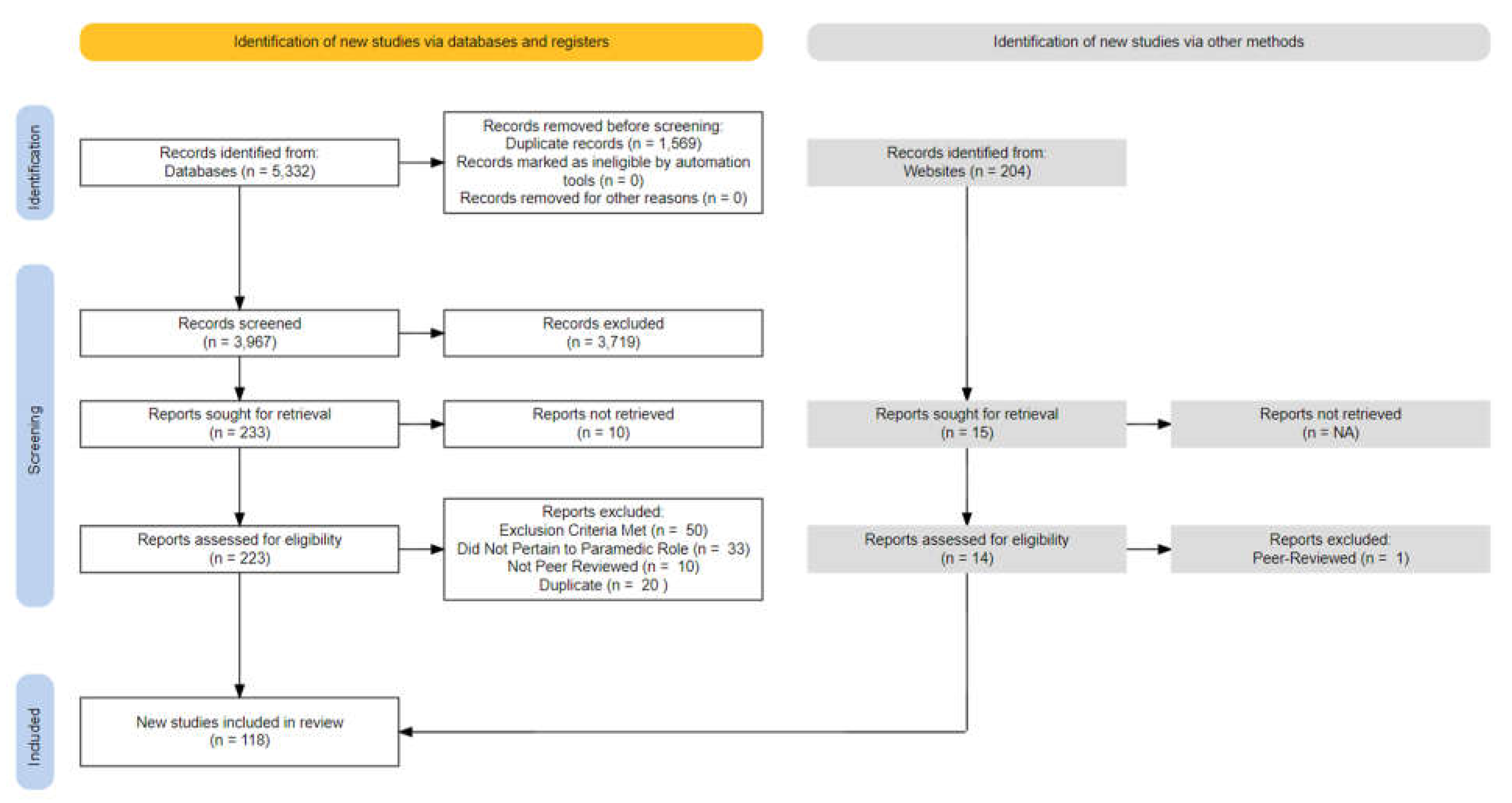

Searches from three databases yielded a total of 5,332 records (Embase: 1,943, CINAHL: 1,765, MEDLINE: 1,530) which led to the removal of 1,569 duplicates. The remaining 3,967 abstracts were screened (see

Figure 1). A manual search of Google Scholar and Google yielded 204 grey-literature articles for abstract screening. The full-text screening phase led to the inclusion of 104 peer-reviewed and 14 grey literature articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Figure 1.

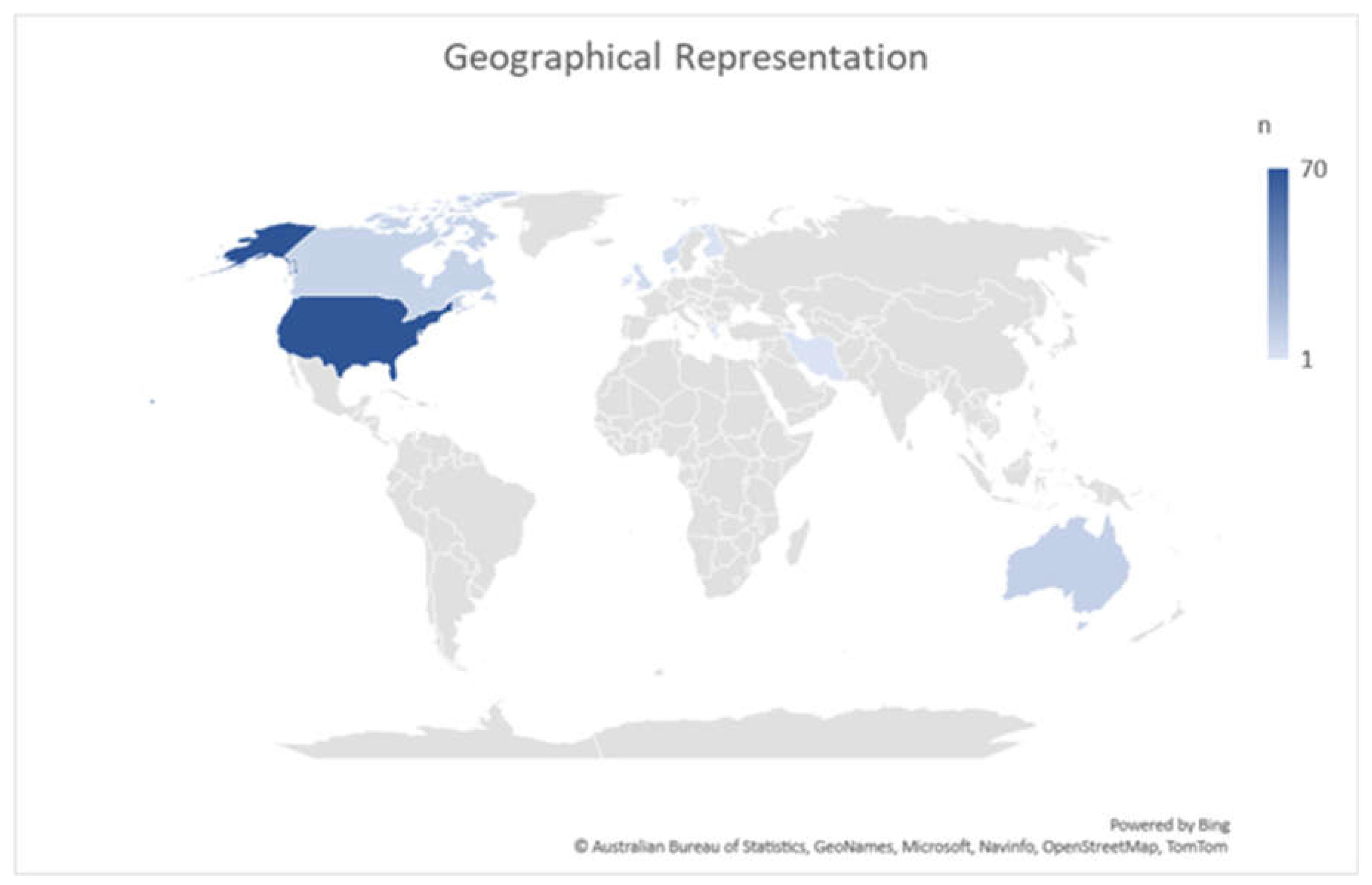

Geographic Representation of Literature.

Figure 1.

Geographic Representation of Literature.

Figure 2.

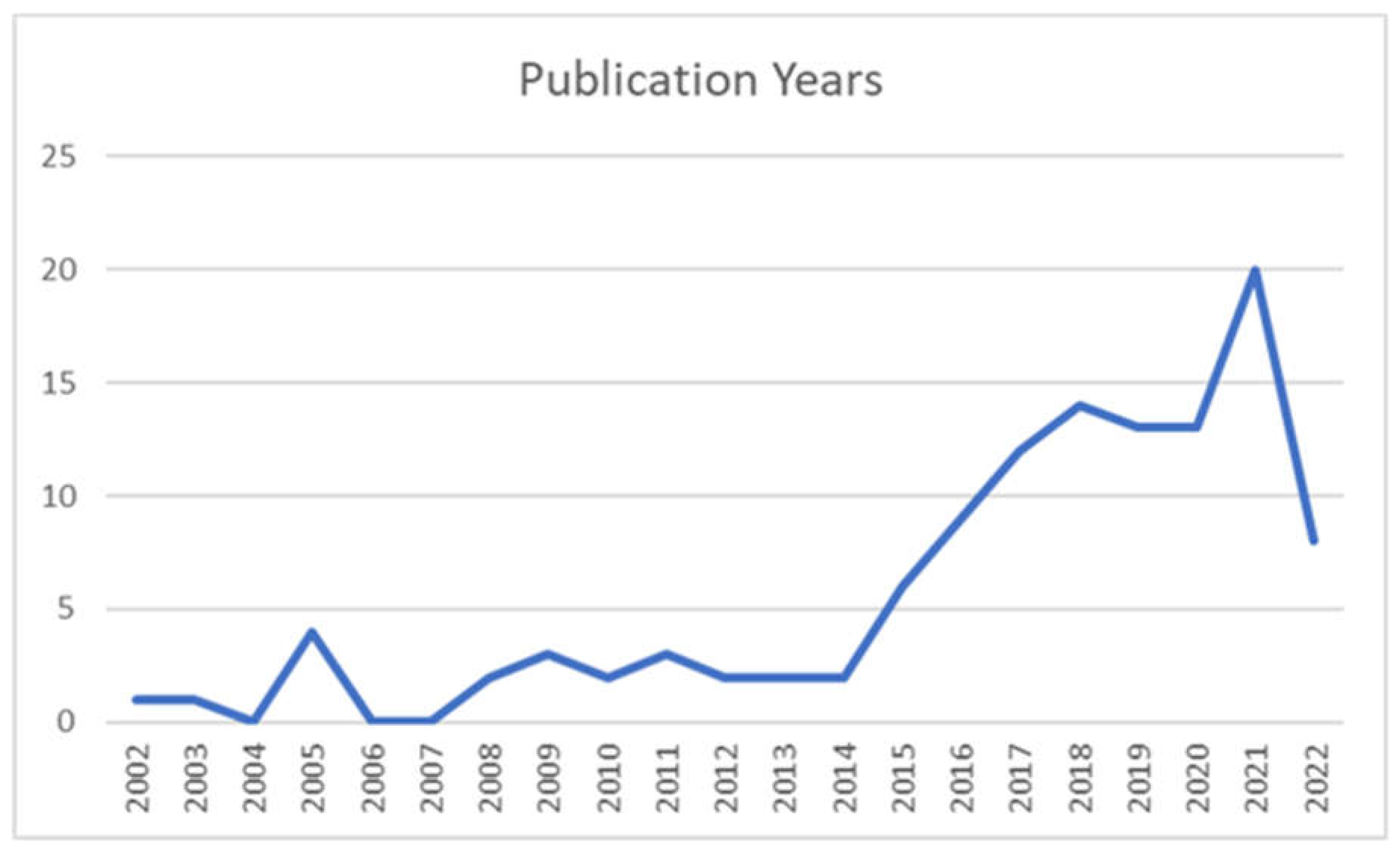

Studies by Publication Year.

Figure 2.

Studies by Publication Year.

Figure 3.

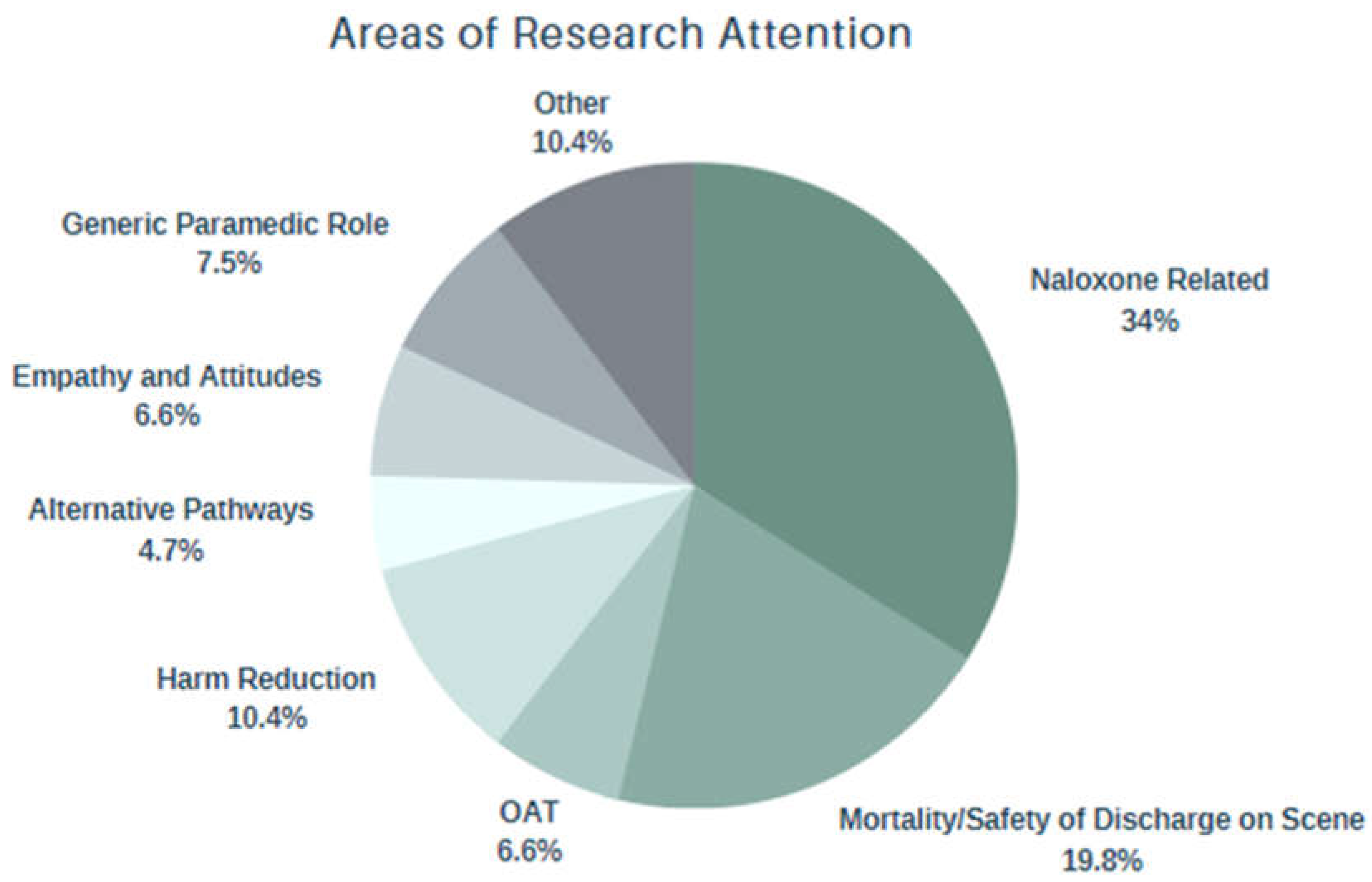

Areas of Research Attention.

Figure 3.

Areas of Research Attention.

The majority of reports included in this review were from the United States (n=87), followed by Australia (n=10), Canada (n=10), and the United Kingdom (n=5) (See

Table 1).

The prevalent methodology utilised in the included peer-reviewed articles were retrospective chart analysis (n=46), followed by qualitative analysis (n=21), literature review (n=10), prospective cohort studies (n=9), non-randomized control trials (n=5), randomized control trials (n=4), mixed methods (n=3), editorial (n=2), consensus guideline (n=1), and case series (n=1). Of the included studies, a small number incorporated the perspectives of PWUD (n=3). Full study characteristics can be found in Appendix 3. The majority of included studies were published in the last decade. In 2021, the most studies were conducted (n=21), and prior to 2017, less than 10 studies per year were produced (see Appendix 4).

Four areas of research attention were iteratively identified in this review: Naloxone access and utilization in the prehospital setting; safety of discharge on scene following a drug poisoning event as well as the incidence of mortality thereafter; the empathy and attitudes of paramedics regarding their role in caring for PWUD; and the expanding contexts of paramedic practice that lend to opportunities for harm reduction.

Naloxone administration

Naloxone access and utilization was the predominant subject of research attention in this review, where 38 articles were included, 29 of which were from the United States. Several studies focused on paramedic utilization of naloxone, all of which concluded that naloxone is a safe and effective treatment modality that should be accessible to all levels of care[

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. 26 articles pertaining to the dose and route of paramedic naloxone administration were included[

22,

23,

24]. Dose-related themes included the sharp increase in which paramedics are administering multiple doses of naloxone[

25,

26]. Findings suggest that one large intramuscular (IM) (1.6mg) or intranasal (IN) (2mg) dose may be sufficient in reversing an opioid-related drug poisoning event, where less than 10% required subsequent dosing upon arrival at the emergency department[

27]. With respect to adverse effects, lower dosages of 0.4mg IM/IN appear to cause less unpleasant symptoms associated with acute withdrawal and have similar effectiveness to higher IN/IM doses[

28]. Relating to sex, paramedics were 18% less likely to administer naloxone to women experiencing a drug poisoning event than their male counterparts[

29].

Naloxone route of administration studies focused on the intranasal route as an efficient, safe, and needleless alternative to parenteral administration, highlighting the nasal cavity as being readily available, pain-free, and faster[

30,

31,

32,

33]. Several included studies found that IN was effective in reversing 74-93.65% of cases, despite the likelihood of requiring re-dosing which was higher than in IV administration[

34,

35]. Despite incidence of re-dosing, cases of complete reversal after one IN dose remained as high as 91% in some studies. Further, the decision to re-dose based on qualitative analysis appears to be subjective and may reflect the practitioner’s reluctance to wait for the desired effects of the drug to take effect[

24].

Mortality Trends and Safety of Discharge on Scene

Safety of discharge on scene and mortality trends following a paramedic-attended drug poisoning event was the second most researched area discovered in this review. 27 articles were included for data extraction, predominantly from the United States (n=18). 12 studies involved the evaluation of mortality trends following an out-of-hospital drug poisoning at as short as 12 hours and as long as five years following the initial encounter. Relevant articles outlined that drug poisoning deaths following a paramedic encounter are more likely due to subsequent use rather than rebound toxicity[

36,

37,

38]. Historical consensus exists that discharge on scene following a drug poisoning event is safe if vital signs are normal, with rare complications arising as a result[

39,

40]. However, more recent studies illustrated that as high as 6.5% (n=787) of people died on the same day as paramedic naloxone administration, and as high as 8.3% (n=807) died within three days. Mortality at 30 days after a drug poisoning increases the risk of death ten-fold and continues to climb thereafter[

41]. Several studies focused on mortality at one year, all of which concluded that incidence of death one year following paramedic administration of naloxone is unacceptably high[

42]. Of the multiple studies that evaluated one year mortality trends, the lowest incidence was 9.9% and the highest was 15.5%.

Expanding opportunities for Paramedic-led harm reduction

Three major paramedic-led harm reducing initiatives discovered in this review were alternative care pathways, paramedic delivered take home naloxone, and paramedic-initiated opioid agonist therapy (OAT). 19 articles discussed novel and holistic approaches to care, 16 of which were from the United States. Emerging evidence indicates that paramedics can help address the crisis by potentially preventing drug poisoning events before they occur[

43,

44]. Several included studies in this review conclude that paramedics are uniquely positioned to offer alternative care options that reduce and prevent drug-related harm[

45,

46].

In addition to alternative care pathways, Naloxone Leave Behind (NLB) programs were reported as promising. Despite some barriers, notable findings included that patients who were offered and accepted a kit were 2.47 times more likely to seek out support services than those that did not accept a kit, and 5.6 times more likely to seek out services when their family was given the NLB kit[

47]. In areas where naloxone is left behind, there was as high as a six-fold likelihood of naloxone being administered prior to paramedic arrival[

48].

Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) is described in this review as an emerging novel treatment option for paramedic care of PWUD. Although results are limited, early findings from pre-hospital OAT trials have been promising, illustrating that 100% of patients who were administered prehospital buprenorphine had an improvement of their opioid withdrawal symptoms, and many remained engaged in OAT at 30 days[

49,

50]. Although buprenorphine is reported as a good “first step”, the emphasis reported in these studies remains on the days following initial administration of OAT, ensuring patients are connected to continuing treatment and or support services[

51]

Further harm reduction opportunities for paramedics identified in this review include specialised community paramedicine, and oral fluid test illicit substance screening[

52,

53]. Community paramedicine has become a highly effective vehicle for harm reduction offering many opportunities for harm reduction including education on needle use, follow-up care following a drug poisoning, and widespread naloxone education and distribution[

54]. Oral fluid testing for substances was reported as being a valuable diagnostic tool in the assessment of unconscious patients due to an unknown cause or intoxication, results expressed that a patient’s treatment was modified based on results of the oral fluid test in 38% of cases[

52].

Empathy and attitudes

A total of seven studies investigated paramedic attitudes and empathy towards their role in caring for PWUD. Regarding harm reduction initiatives, paramedic attitudes towards them are polarized, some refusing to participate in programs altogether. Of all patient demographics, substance use was associated with the lowest mean empathy scores by a large margin[

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Some paramedic students went as far as relaying a perception that PWUD are unworthy of medical treatment, and a burden on the medical system. Further reported is the degree at which student empathy levels appear to decline (in general) over the course of their education, whereas students with previous addiction and substance use education were significantly less likely to stigmatize this population[

60].

Five major themes identified by a study of paramedic attitudes in Vancouver, BC included: connecting with patients’ lived experiences; occupying roles as clinicians and patient advocates; navigating on-scene hazards; difficulties with transitions of care; and emotional burden of the toxic drug crisis[

61]. The core category discovered from this study was one’s capacity to help, identified by a limited capacity to follow up on patients, to emotionally process stressful encounters, and to address the needs of a patient who experiences a drug poisoning event. Despite paramedics feeling highly confident in their role as clinical care provision, their capacity to treat the underlying drug use is described as much more limited.

4. Discussion

This scoping review sought to explore what is known about the paramedic role in caring for PWUD. Our searches highlighted 118 articles from 10 countries between 2002 and 2022. Our findings illustrate that people who experience an out-of-hospital drug poisoning have extremely high mortality rates, and the literature is largely focused on responsive models of patient care. Despite calls for a move towards more holistic care[

62], little guidance on how paramedicine may transition to said models of care was discovered. We observed stigma associated with drug use, and diverging perspectives of harm mitigation among paramedics, which present a barrier to implementing harm reduction programs. Finally, and perhaps of greatest concern, our study revealed a significant lack of engagement with the perspectives of PWUD in the existing literature.

The traditional role of the paramedic at a drug poisoning event is a responsive and reactive one, focused on rapid emergency response, resuscitation, and reversal of the opioid toxidrome. This traditional role has positioned paramedics as the first point of medical contact with the health care system for PWUD for decades[

63]. Prior to the beginning of the toxic drug crisis, paramedics were able to reverse opioid toxicity with relative ease, and the subsequent care after reversal did not involve paramedics. However, in recent years the steady increase in drug toxicity has complicated the traditional response[

64]. Paramedics spend significantly more time on scene with patients in the resuscitation phase, struggling to reverse a drug poisoning complicated by potent and co-intoxicating substances that may not respond to naloxone administration. Further complicating traditional response is the significant decrease in emergency department conveyance following a drug poisoning, coupled with a marked decrease in 911 calling at the event[

65]. Given the correlation between ED non-conveyance and increased mortality, there is now a narrowing window of opportunity for paramedics to positively influence a patient’s journey through the health care system and reduce drug related harm. Despite a decrease in 911 calling, the rate at which paramedics encounter PWUD continues to surge, further positioning them to offer alternative models of care that do not necessitate ED conveyance.

Throughout all contexts of practice within paramedicine, the focus of the paramedic role is shifting from one that is somewhat responsive and linear, to a holistic “system navigator”. Today, paramedics advocate for a patient’s wants, needs, and rights which can involve alternative destination pathways, outreach and referral, community care, and more. Despite an awareness that this shift will benefit patients, and may benefit paramedics, this shift in the paramedic role in caring for PWUD specifically remains unexplored.

The role of the paramedic in the toxic drug crisis is complicated by increasing burnout, helplessness, and moral distress among paramedics. A once rewarding patient encounter for paramedics has evolved into one which may leave both parties (the patient and the paramedic) feeling dissatisfied. The consequences of being left on scene while experiencing acute withdrawal may lead to subsequent substance use to stave off undesirable symptoms, potentially leading to further drug poisoning events. The downstream effects of subsequent drug poisonings on paramedics can manifest as multiple resuscitations, sometimes of the same patient, lending to a sense of harbored helplessness[

66]. This has contributed to a notion described by paramedics as being confident in treating a drug poisoned patient, but lacking in the ability to treat the underlying cause. Further, introducing paramedic-led harm reduction programs such as referral pathways, take home naloxone programs, and treatment of acute withdrawal[

67] has the potential to not only break the drug poisoning cycle for patients, but also break the responsive cycle for paramedics and expand their capacity to help. Implementing such programs require the involvement of key stakeholders and harm reduction subject matter experts, as well as PWUD to ensure patient-centric, non-paternalistic approaches to develop trust. Program success however will depend on paramedic engagement, an apparent barrier to success discovered within this review.

Such divergent views related to harm reduction among paramedics is perhaps the greatest barrier to program success. Some paramedics describe harm reduction programs as enabling riskier drug use and being ineffective in reducing drug-related deaths. These misconceptions have influenced some paramedics to reject drug-related harm reduction as a context of practice. Compassion fatigue and cumulative stress are potential contributory factors. However, these constructs may begin to form as early as initial paramedic education. Multiple studies identified in this review revealed that paramedic students have the lowest levels of empathy for PWUD than any other patient population, and in some cases their empathy decreases throughout their education. To what extent paramedic education contributes to, or neglects to address provider-based stigma is not well understood and requires urgent research attention. In the absence of clinician buy-in towards harm reducing programs, evaluation of program success will be limited and misrepresented. Whether formal harm reduction programs are implemented or not, non-judgmental, and an empathetic approach that includes the use of non-stigmatizing language are harm reduction approaches that can be integrated into an individual paramedic’s practice instantly.

The relationship between paramedics and PWUD has historical underpinnings that have caused confused and at times hostile perceptions. By choosing to use language that embodies an empathetic approach towards PWUD, feelings of guilt and shame which can cause a person to isolate and use drugs alone, can be suppressed. The relationship between provider-based stigma or attitudes and decreased activation of the 911 system is not well understood. However, many PWUD perceive calling for paramedics as akin to calling for police. Decreasing police presence at a drug poisoning may have the potential to reduce on-scene tension bred from long-standing negative associations which may have stemmed from inter-generational trauma, criminalization, and stigma. Improving the relationship between PWUD and the 911 system must begin with and be sustained by the ethical engagement with PWUD in service design and delivery. It should be acknowledged that in some areas, due to delayed wait times and other complicating contributors, the relationship between PWUD and the 911 system is strained[

68]. The importance of the paramedic role in caring for PWUD however will simply not be fully realized without this collaborative approach. Despite three studies included in this review seeking perspectives of PWUD, only one focused on them. PWUD offered key insights towards the barriers of harm reduction, such as the willingness to call 911, as well as the opportunities, such as the sentiment that 911-initiated post-overdose interventions can be viewed as lifesaving[

69]. Success to a health care organization may not be defined as success to PWUD, and vice versa; thus, organizations that do not consult with PWUD will likely struggle with the success of patient-oriented outcomes within their programs.

Limitations

Our study needs to be considered in the context of its limitations. We may not have identified all relevant studies despite attempts to be comprehensive. While our search strategy included terms previously used to describe drug use, others may exist. The keywords used to index papers lack consistency and a wide variety of descriptive terms are used in abstracts. Our search and review were restricted to articles published in English, but this does not inherently bias a review. The Google Scholar search was limited to the first 1000 results. Studies included in this review predominantly focused on the use of opioids, with limited focus on illicit stimulants, and non-opioid CNS depressants. The role of the paramedic in caring for people who use stimulants and non-opioid CNS depressants is grossly underrepresented in the literature. Despite these limitations, we suggest our review offers a comprehensive overview of the role of paramedics in caring for PWUD, along with suggestions for future directions and research.

5. Conclusion

In caring for PWUD, paramedics play an understudied role in the patient’s journey through the health care system with multiple gaps in knowledge directed towards alternative and holistic models of care. This scoping review aimed to summarize the current literature surrounding drug-related substance use, and the paramedic role. Of upmost importance, patient perspectives must be included in future research involving system level changes that may influence and affect their care. PWUD interact with paramedics at a high rate, and this interaction may directly correlate to patient harm. This encounter presents an opportunity for paramedics to reduce harm at various stages throughout a patient’s journey outside of the reversal of a drug poisoning event alone. Strategies including alternative care referral pathways, NLB programs, community paramedic outreach, paramedic-initiation of OAT, and even harm-reducing and educational conversations are examples of non-traditional responsive models that have the potential to synergistically reduce harms on both sides of the paramedic encounter with PWUD. By giving paramedics the tools to provide holistic care that extends past the reversal of a drug poisoning event, we are theoretically building their resilience and sense of purpose, potentially improving paramedic wellness, job satisfaction, and empathy towards PWUD. Given the powerful influence of the paramedic role in a patient’s journey through the healthcare system, this review represents a highly understudied area that requires significant research attention.

Funding

No funding was obtained to complete this study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

Search results and screening information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

No ethics approval was required for this scoping review as no human participants were involved.

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Declared in title page.

References

- Greene, J.A.; Deveau, B.J.; Dol, J.S.; Butler, M.B. Incidence of mortality due to rebound toxicity after a 'treat and release' practices in prehospital opioid overdose care: A systematic review. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2019, 36, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2. McLeod KE, Slaunwhite AK, Zhao B, Moe J, Purssell R, Gan W, et al. Comparing mortality and healthcare utilization in the year following a paramedic-attended non-fatal overdose among people who were and were not transported to hospital: A prospective cohort study using linked administrative health data. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2021; 218, N.PAG–N.PAG.

- Weiner, S.G.; Baker, O.; Bernson, D.; Schuur, J.D. One year mortality of patients treated with naloxone for opioid overdose by emergency medical services. Substance abuse. 2022, 43, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburn NP, Ryder CW, Angi RM, Snavely AC, Nelson RD, Bozeman WP, et al. One-Year Mortality and Associated Factors in Patients Receiving Out-of-Hospital Naloxone for Presumed Opioid Overdose. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2020, 75, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barefoot EH, Cyr JM, Brice JH, Bachman MW, Williams JG, Cabanas JG, et al. Opportunities for Emergency Medical Services Intervention to Prevent Opioid Overdose Mortality. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021, 25, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, A.; Kumar, L.; Barhorst, B.; Braithwaite, S. The Role of Emergency Medical Services in the Opioid Epidemic. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021, 25, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics, N.C.f.D.A. Drug Overdose Death Rates 2022 [cited 2022 2022]. Available from: https://drugabusestatistics.org/drug-overdose-deaths/.

- BCCS. BC Coroner's Service Death Review Panel: A Review of Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths. 2022.

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Library, J.A.L. Addiction: Keyword Suggestions for Searches: Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology 2022 [updated August 2022.

- Insitute, T.J.B. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2022 [Available from: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/jbi/docs/reviewersmanuals/scoping-.pdf.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 13. Neal Haddaway AC, Deborah Coughlin, Stuart Kirk. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10.

- Piasecki, J.; Waligora, M.; Dranseika, V. Google Search as an Additional Source in Systematic Reviews. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018, 24, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Langlois, E.V.; Straus, S.E.; Alliance for Health, P.; Systems, R.; World Health, O. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.M.K. Descriptive Statistics.

- Gulec, N.; Lahey, J.; Suozzi, J.C.; Sholl, M.; MacLean, C.D.; Wolfson, D.L. Basic and Advanced EMS Providers Are Equally Effective in Naloxone Administration for Opioid Overdose in Northern New England. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2018, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent K, Matthews P, Gissendaner J, Papas M, Occident D, Patel A, et al. A Comparison of Efficacy of Treatment and Time to Administration of Naloxone by BLS and ALS Providers. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine. 2019, 34, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wagner, K.D.; Marchand, C.; Klass, E.M.; Sullivan, B. Naloxone access for Emergency Medical Technicians: An evaluation of a training program in rural communities. Addictive Behaviors. 2018; 86, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman, J.M.; Robinson, K. National Systematic Legal Review of State Policies on Emergency Medical Services Licensure Levels' Authority to Administer Opioid Antagonists. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2018, 22, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 21. Davis CS, Southwell JX, Niehaus VR, Walley AY, Dailey MW. EMS access to naloxone-a national systematic legal review. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014; 21, S129.

- McDermott, C.; Collins, N.C. Prehospital medication administration: A randomised study comparing intranasal and intravenous routes. Emergency Medicine International. 2012, 2012((McDermott) Centre for Emergency Medical Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland(Collins) Medical Advisory Group, Pre-hospital Emergency Care Council in Ireland, Naas, Ireland):476161.

- Skulberg AK, Tylleskar I, Valberg M, Braarud AC, Dale J, Heyerdahl F, et al. Comparison of intranasal and intramuscular naloxone in opioid overdoses managed by ambulance staff: a double-dummy, randomised, controlled trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2022((Skulberg, Tylleskar, Dale) Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway(Skulberg, Braarud, Heyerdahl, Skalhegg, Mellesmo) Division of Prehospital Services, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo).

- Merlin MA, Saybolt M, Kapitanyan R, Alter SM, Jeges J, Liu J, et al. Intranasal naloxone delivery is an alternative to intravenous naloxone for opioid overdoses. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010, 28, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, M.; Lurie, P.; Kinsman, J.M.; Dailey, M.W.; Crabaugh, C.; Sasser, S.M. Multiple Naloxone Administrations Among Emergency Medical Service Providers is Increasing. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2017, 21, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.L.; Falaiye, O.; Foley, D.; Dunne, R. Factors associated with naloxone administration in an urban fire-based emergency medical services system. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018; 25, S177. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, K.; Dietze, P.; Flander, L. The relationship between naloxone dose and key patient variables in the treatment of non-fatal heroin overdose in the prehospital setting. Resuscitation. 2005, 65, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson J, Salter J, Bui P, Herbert L, Mills D, Wagner D, et al. Safety, Efficacy, and Cost of 0.4-mg Versus 2-mg Intranasal Naloxone for Treatment of Prehospital Opioid Overdose. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2022, 56, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettano, A.; Jones, K.; Fillo, K.T.; Ficks, R.; Bernson, D. Opioid-related incident severity and emergency medical service naloxone administration by sex in Massachusetts, 2013-2019. Substance abuse. 2022, 43, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 30. Yousefifard M, Vazirizadeh-Mahabadi MH, Neishaboori AM, Alavi SNR, Amiri M, Baratloo A, et al. Intranasal versus Intramuscular/Intravenous Naloxone for Pre-hospital Opioid Overdose: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Advanced Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 4.

- Robertson, T.M.; Hendey, G.W.; Stroh, G.; Shalit, M. Intranasal naloxone is a viable alternative to intravenous naloxone for prehospital narcotic overdose. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2009, 13, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, S.G.; Mitchell, P.M.; Temin, E.S.; Langlois, B.K.; Dyer, K.S. Use of Intranasal Naloxone by Basic Life Support Providers. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2017, 21, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, D.; Dietze, P.; Kelly, A. Intranasal naloxone for the treatment of suspected heroin overdose. Addiction. 2008, 103, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton ED, Colwell CB, Wolfe T, Fosnocht D, Gravitz C, Bryan T, et al. Efficacy of intranasal naloxone as a needleless alternative for treatment of opioid overdose in the prehospital setting. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2005, 29, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.M.; Tataris, K.L.; Hoffman, J.D.; Aks, S.E.; Mycyk, M.B. Can Nebulized Naloxone Be Used Safely and Effectively by Emergency Medical Services for Suspected Opioid Overdose? ? Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012, 16, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, S.S.; Jehu, G.; Nielsen, S.L.; Nielsen, K.; Siersma, V.; Rasmussen, L.S. Prehospital treatment of opioid overdose in Copenhagen-Is it safe to discharge on-scene? Resuscitation. 2011, 82, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wampler, D.A.; Molina, D.K.; McManus, J.; Laws, P.; Manifold, C.A. No deaths associated with patient refusal of transport after naloxone-reversed opioid overdose. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2011, 15, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stam, N.C.; Pilgrim, J.L.; Drummer, O.H.; Smith, K.; Gerostamoulos, D. Catch and release: evaluating the safety of non-fatal heroin overdose management in the out-of-hospital environment. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa). 2018, 56, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolinsky, D.; Keim, S.M.; Cohn, B.G.; Schwarz, E.S.; Yealy, D.M. Is a Prehospital Treat and Release Protocol for Opioid Overdose Safe? Journal of Emergency Medicine (0736-4679). 2017, 52, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willman, M.W.; Liss, D.B.; Schwarz, E.S.; Mullins, M.E. Do heroin overdose patients require observation after receiving naloxone? Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa). 2017, 55, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjersing, L.; Bretteville-Jensen, A.L. Are overdoses treated by ambulance services an opportunity for additional interventions? A prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2015, 110, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, S.G.; Baker, O.; Bernson, D.; Schuur, J.D. One year mortality of patients treated with naloxone for opioid overdose by emergency medical services. Substance Abuse.

- Swayze, D. OVERDOSE PREVENTION: Managing the opioid epidemic with mobile integrated healthcare programs. JEMS: Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 2017, 42, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Taxel S, Nrp, Ba. 2018. Available from: https://www.jems.com/patient-care/beyond-naloxone-providing-comprehensive-prehospital-care-to-overdose-patients-in-the-midst-of-a-public-health-crisis/.

- Langabeer, J.R.; Persse, D.; Yatsco, A.; O'Neal, M.M.; Champagne-Langabeer, T. A Framework for EMS Outreach for Drug Overdose Survivors: A Case Report of the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021, 25, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.S.; Elliott, L.; Bennett, P.I.R.S.A.S.; Elliott, P.I.R.S.L. Naloxone's role in the national opioid crisis-past struggles, current efforts, and future opportunities. Translational Research: The Journal of Laboratory & Clinical Medicine. 2021, 234, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, B.M.; Sabat, D.J.; Brothers, J.M.; Margolis, A.M.; Levy, M.J. Best Practices for a Novel EMS-Based Naloxone Leave behind Program. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021, 25, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbridge, T.R.; Miller, S.N. Emergency Medical Services Buprenorphine: Just Because They Can? Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2021, 78, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zozula, A.; Neth, M.R.; Hogan, A.N.; Stolz, U.; McMullan, J. Non-transport after Prehospital Naloxone Administration Is Associated with Higher Risk of Subsequent Non-fatal Overdose. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2022, 26, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll GG, Wasserman DD, Shah AA, Salzman MS, Baston KE, Rohrbach RA, et al. Buprenorphine Field Initiation of ReScue Treatment by Emergency Medical Services (Bupe FIRST EMS): A Case Series. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021, 25, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, J. 2021. Available from: https://www.jems.com/operations/pittsburgh-pa-ems-begins-administering-buprenorphine-for-opioid-overdoses/.

- Söderqvist, M.; Virta, J.; Kämäräinen, A. Substance Abuse Among Emergency Medical Service Patients: A Pilot Study on the Clinical Impact of an On-site Oral Fluid Screening Test. Point of Care. 2018, 17, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, J.R.; Swayze, D. Community paramedics ad the Drug-Seeker. EMS World. 2016, 45, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Community Paramedicine and Harm Reduction for Substance Abuse. Julota. 2022.

- Pagano A, Robinson K, Ricketts C, Cundy-Jones J, Henderson L, Cartwright W, et al. Empathy Levels in Canadian Paramedic Students: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2018, 11, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Boyle, M.; Fielder, C. Empathetic attitudes of undergraduate paramedic and nursing students towards four medical conditions: A three-year longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today. 2015, 35, e14–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruis, N.E.; McLean, K.; Perry, P. Exploring first responders' perceptions of medication for addiction treatment: Does stigma influence attitudes? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021, 131:N.PAG-N.PAG.

- Brett W, Malcolm B, Richard B, Scott D, Peter H, Michael M, et al. An assessment of undergraduate paramedic students' empathy levels: A multi-institutional study. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine. 2013, 10, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, H.; Chloe, E.-V.; Malcolm, B.; Brett, W. Do first year paramedic have preconceived attitudes about patients with specific medical conditions? A four-year longitudinal study. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine. 2013, 10, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Kruis, N.E.; Choi, J. Exploring social stigma toward opioid and heroin users among students enrolled in criminology, nursing, and EMT/paramedic courses. Journal of Criminal Justice Education. 2020, 31, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Yuen J, Minaker G, Buxton J, Gadermann A, Palepu A. 'You're not just a medical professional': Exploring paramedic experiences of overdose response within Vancouver's downtown eastside. PloS one. 2020, 15, e0239559. [Google Scholar]

- Educating Paramedics for the Future: A Holistic Approach | Journal of Health and Human Services Administration.

- Canada, Go. Opioid-related Harms in Canada: Integrating Emergency Medical Service, hospitalization, and death data 2022 [Available from: Opioid-related Harms in Canada: Integrating Emergency Medical Service, hospitalization, and death data.

- Beaugard, C.A.; Hruschak, V.; Lee, C.S.; Swab, J.; Roth, S.; Rosen, D. Emergency medical services on the frontlines of the opioid overdose crisis: the role of mental health, substance use, and burnout. International Journal of Emergency Services. 2022, ahead-of-print.

- Rock P, Singleton M. EMS Heroin Overdoses with Refusal to Transport & Impacts on ED Overdose Surveillance. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2019, 11, e430. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, E.; Tillson, M.; Webster, J.M.; Staton, M. A mixed-methods assessment of the impact of the opioid epidemic on first responder burnout. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2019; 205, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll G, Solomon KT, Heil J, Saloner B, Stuart EA, Patel EY, et al. Impact of Administering Buprenorphine to Overdose Survivors Using Emergency Medical Services. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2022.

- Mamdani Z, Loyal JP, Xavier J, Pauly B, Ackermann E, Barbic S, et al. ‘We are the first responders’: overdose response experiences and perspectives among peers in British Columbia. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2022:1-14.

- Wagner KD, Harding RW, Kelley R, Labus B, Verdugo SR, Copulsky E, et al. Post-overdose interventions triggered by calling 911: Centering the perspectives of people who use drugs (PWUDs). PloS one. 2019, 14, e0223823. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Study Locations.

Table 1.

Study Locations.

| Country |

n |

% |

| United States |

10 |

67 |

| Australia |

10 |

10 |

| Canada |

9 |

9 |

| United Kingdom |

5 |

5 |

| Norway |

5 |

5 |

| Denmark |

1 |

1 |

| Finland |

1 |

1 |

| Greece |

1 |

1 |

| Iran |

1 |

1 |

| Ireland |

1 |

1 |

| Grey Literature Study Locations |

| United States |

14 |

100 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).