Submitted:

04 February 2023

Posted:

06 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Myocarditis

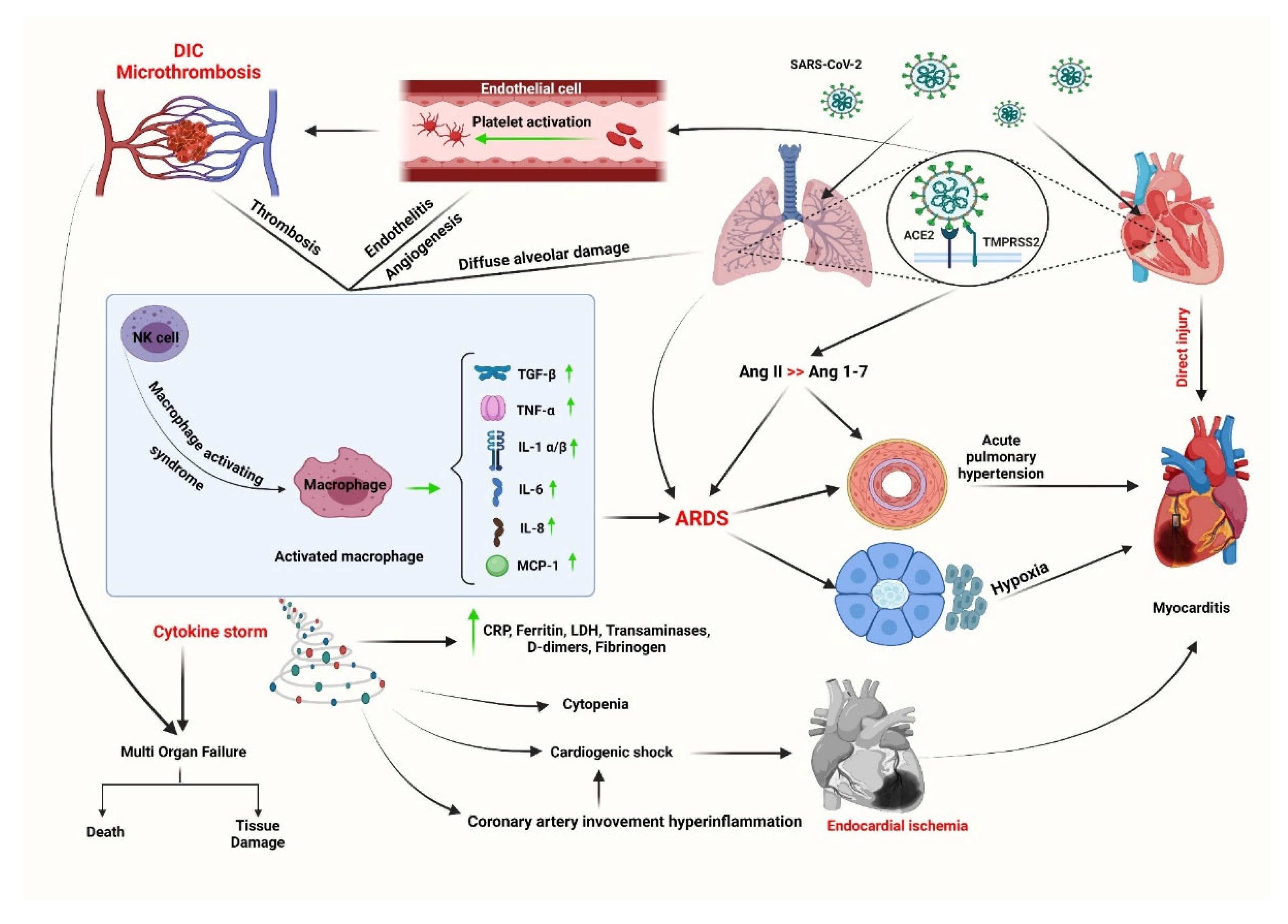

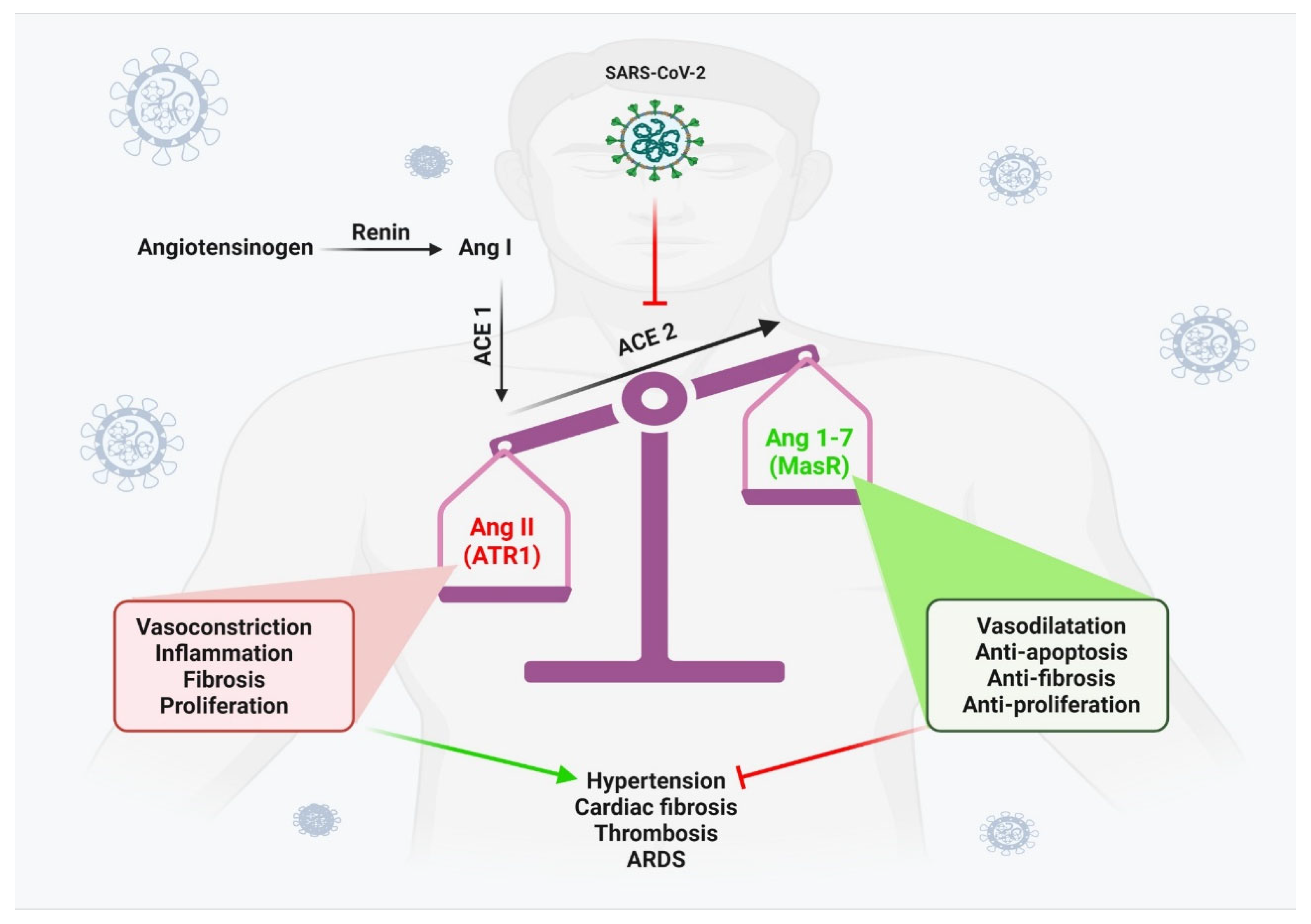

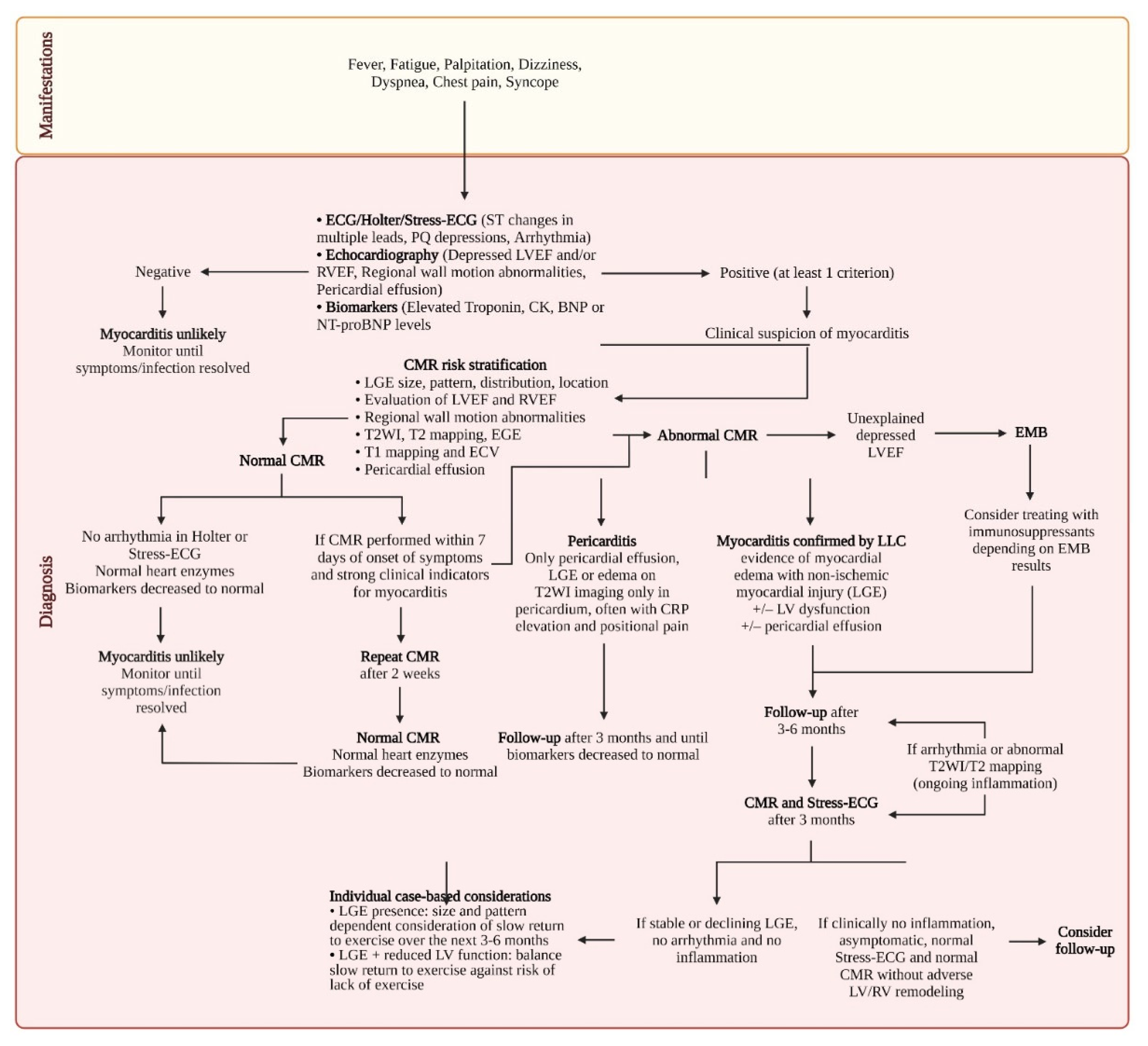

2.1. COVID-related myocarditis

3. COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis

3. Pericarditis

4. COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

References

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, M.R.; Bularga, A.; Hahn, R.T.; Bing, R.; Lee, K.K.; Chapman, A.R.; White, A.; Salvo, G.D.; Sade, L.E.; Pearce, K. Global evaluation of echocardiography in patients with COVID-19. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging 2020, 21, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntmann, V.O.; Carerj, M.L.; Wieters, I.; Fahim, M.; Arendt, C.; Hoffmann, J.; Shchendrygina, A.; Escher, F.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Zeiher, A.M.; et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiology 2020, 5, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahranavard, M.; Rezayat, A.A.; Bidary, M.Z.; Omranzadeh, A.; Rohani, F.; Farahani, R.H.; Hazrati, E.; Mousavi, S.H.; Ardalan, M.A.; Soleiman-Meigooni, S. Cardiac complications in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Iranian medicine 2021, 24, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.-C.; Wang, P. Cardiovascular complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in cardiovascular medicine 2021, 22, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiology 2020, 5, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation 2022, 146, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuvali, O.; Tshori, S.; Derazne, E.; Hannuna, R.R.; Afek, A.; Haberman, D.; Sella, G.; George, J. The Incidence of Myocarditis and Pericarditis in Post COVID-19 Unvaccinated Patients—A Large Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 2219. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, B.J.R.; Harrison, S.L.; Fazio-Eynullayeva, E.; Underhill, P.; Lane, D.A.; Lip, G.Y.H. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of myocarditis and pericarditis in 718,365 COVID-19 patients. Eur J Clin Invest 2021, 51, e13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, L.; Morgan, M.; Harrell, S.; AlJaroudi, W.; Berman, A.E. Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19 related myocarditis: clinical and imaging considerations. World Journal of Radiology 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripanthong, B.; Nazarian, S.; Muser, D.; Deo, R.; Santangeli, P.; Khanji, M.Y.; Cooper, L.T., Jr.; Chahal, C.A.A. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart rhythm 2020, 17, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.B. SARS-CoV-2 Myocarditis in a High School Athlete after COVID-19 and Its Implications for Clearance for Sports. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardiology, E.S.o. ESC Guidance for the Diagnosis and Management of CV Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic; 10 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Doyen, D.; Moceri, P.; Ducreux, D.; Dellamonica, J. Myocarditis in a patient with COVID-19: a cause of raised troponin and ECG changes. Lancet 2020, 395, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardari, A.; Tabarsi, P.; Borhany, H.; Mohiaddin, R.; Houshmand, G. Myocarditis detected after COVID-19 recovery. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2021, 22, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.F.; Charles, P.; Richaud, C.; Caussin, C.; Diakov, C. Myocarditis revealing COVID-19 infection in a young patient. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 21, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, Q.; Brillat-Savarin, N.; Ducrocq, G.; Ou, P. Case report of an isolated myocarditis due to COVID-19 infection in a paediatric patient. European Heart Journal: Case Reports 2020, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Most, Z.M.; Hendren, N.; Drazner, M.H.; Perl, T.M. Striking Similarities of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and a Myocarditis-Like Syndrome in Adults. Circulation 2021, 143, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Porritt, R.A.; Cheng, M.H.; Bahar, I.; Arditi, M. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Long COVID: The SARS-CoV-2 Viral Superantigen Hypothesis. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; Kelleman, M.; West, Z.; Peter, A.; Dove, M.; Butto, A.; Oster, M.E. Comparison of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children-Related Myocarditis, Classic Viral Myocarditis, and COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Myocarditis in Children. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e024393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inciardi, R.M.; Lupi, L.; Zaccone, G.; Italia, L.; Raffo, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Cani, D.S.; Cerini, M.; Farina, D.; Gavazzi, E.; et al. Cardiac Involvement in a Patient With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.X.; Wu, W.B.; Li, J.X.; Wang, L.F.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Dong, C.F.; et al. First case of COVID-19 complicated with fulminant myocarditis: a case report and insights. Infection 2020, 48, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siripanthong, B.; Nazarian, S.; Muser, D.; Deo, R.; Santangeli, P.; Khanji, M.Y.; Cooper Jr, L.T.; Chahal, C.A.A. Recognizing COVID-19–related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart rhythm 2020, 17, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Han, K.; Suh, Y.J. Prevalence of abnormal cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in recovered patients from COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2021, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussner, W.; DeRosa, A.P.; Haussner, D.; Tran, J.; Torres-Lavoro, J.; Kamler, J.; Shah, K. COVID-19 associated myocarditis: A systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 2022, 51, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, D.; Flamigni, F.; Rapezzi, C.; Ferrari, R. Myocarditis in COVID-19 patients: current problems. Intern Emerg Med 2021, 16, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagana, N.; Cei, M.; Evangelista, I.; Cerutti, S.; Colombo, A.; Conte, L.; Mormina, E.; Rotiroti, G.; Versace, A.G.; Porta, C.; et al. Suspected myocarditis in patients with COVID-19: A multicenter case series. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e24552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivara, M.B.; Bajwa, E.K.; Januzzi, J.L.; Gong, M.N.; Thompson, B.T.; Christiani, D.C. Prognostic significance of elevated cardiac troponin-T levels in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imazio, M.; Klingel, K.; Kindermann, I.; Brucato, A.; De Rosa, F.G.; Adler, Y.; De Ferrari, G.M. COVID-19 pandemic and troponin: indirect myocardial injury, myocardial inflammation or myocarditis? Heart 2020, 106, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kociol, R.D.; Cooper, L.T.; Fang, J.C.; Moslehi, J.J.; Pang, P.S.; Sabe, M.A.; Shah, R.V.; Sims, D.B.; Thiene, G.; Vardeny, O. Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e69–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeboye, A.; Alkhatib, D.; Butt, A.; Yedlapati, N.; Garg, N. A Review of the Role of Imaging Modalities in the Evaluation of Viral Myocarditis with a Special Focus on COVID-19-Related Myocarditis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nensa, F.; Kloth, J.; Tezgah, E.; Poeppel, T.D.; Heusch, P.; Goebel, J.; Nassenstein, K.; Schlosser, T. Feasibility of FDG-PET in myocarditis: Comparison to CMR using integrated PET/MRI. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology 2018, 25, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozieranski, K.; Tyminska, A.; Kobylecka, M.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Sobic-Saranovic, D.; Ristic, A.D.; Maksimovic, R.; Seferovic, P.M.; Marcolongo, R.; Krolicki, L.; et al. Positron emission tomography in clinically suspected myocarditis - STREAM study design. Int J Cardiol 2021, 332, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, I.; Sathekge, M. F-18 FDG PET/CT imaging of cardiac and vascular inflammation and infection. British Medical Bulletin 2016, 120, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luetkens, J.A.; Faron, A.; Isaak, A.; Dabir, D.; Kuetting, D.; Feisst, A.; Schmeel, F.C.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Thomas, D. Comparison of Original and 2018 Lake Louise Criteria for Diagnosis of Acute Myocarditis: Results of a Validation Cohort. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2019, 1, e190010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.M.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Holmvang, G.; Kramer, C.M.; Carbone, I.; Sechtem, U.; Kindermann, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Cooper, L.T.; Liu, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 3158–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, S.; Peretto, G.; Gramegna, M.; Palmisano, A.; Villatore, A.; Vignale, D.; De Cobelli, F.; Tresoldi, M.; Cappelletti, A.M.; Basso, C. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. European heart journal 2020, 41, 1861–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, N.R. Viral myocarditis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2016, 28, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia, L.; Tomasoni, D.; Bisegna, S.; Pancaldi, E.; Stretti, L.; Adamo, M.; Metra, M. COVID-19 and heart failure: from epidemiology during the pandemic to myocardial injury, myocarditis, and heart failure sequelae. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.D.; Millar, J.E.; Baillie, J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. The Lancet 2020, 395, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawalha, K.; Abozenah, M.; Kadado, A.J.; Battisha, A.; Al-Akchar, M.; Salerno, C.; Hernandez-Montfort, J.; Islam, A.M. Systematic Review of COVID-19 Related Myocarditis: Insights on Management and Outcome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2021, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Sun, Y.; Su, G.; Li, Y.; Shuai, X. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for acute myocarditis in children and adults a meta-analysis. International heart journal 2019, 60, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Ma, F.; Wei, X.; Fang, Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis treated with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. European heart journal 2021, 42, 206–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirzada, A.; Mokhtar, A.T.; Moeller, A.D. COVID-19 and myocarditis: what do we know so far? CJC open 2020, 2, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agdamag, A.C.C.; Edmiston, J.B.; Charpentier, V.; Chowdhury, M.; Fraser, M.; Maharaj, V.R.; Francis, G.S.; Alexy, T. Update on COVID-19 Myocarditis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020, 56, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, B.J.R.; Harrison, S.L.; Fazio-Eynullayeva, E.; Underhill, P.; Lane, D.A.; Lip, G.Y.H. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of myocarditis and pericarditis in 718,365 COVID-19 patients. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2021, 51, e13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mevorach, D.; Anis, E.; Cedar, N.; Bromberg, M.; Haas, E.J.; Nadir, E.; Olsha-Castell, S.; Arad, D.; Hasin, T.; Levi, N. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 2140–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, M.E.; Shay, D.K.; Su, J.R.; Gee, J.; Creech, C.B.; Broder, K.R.; Edwards, K.; Soslow, J.H.; Dendy, J.M.; Schlaudecker, E.; et al. Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US From December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.T.; Dionne, A.; Muniz, J.C.; McHugh, K.E.; Portman, M.A.; Lambert, L.M.; Thacker, D.; Elias, M.D.; Li, J.S.; Toro-Salazar, O.H.; et al. Clinically Suspected Myocarditis Temporally Related to COVID-19 Vaccination in Adolescents and Young Adults: Suspected Myocarditis After COVID-19 Vaccination. Circulation 2022, 145, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevorach, D.; Anis, E.; Cedar, N.; Bromberg, M.; Haas, E.J.; Nadir, E.; Olsha-Castell, S.; Arad, D.; Hasin, T.; Levi, N.; et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 2140–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, R.E.; Love, S.S.; Atwood, J.E.; Arness, M.K.; Cassimatis, D.C.; Campbell, C.L.; Boyd, S.Y.; Murphy, J.G.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Collins, L.C.; et al. Incidence and follow-up of inflammatory cardiac complications after smallpox vaccination. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004, 44, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Halsey, N.A.; Omer, S.B.; Orenstein, W.A.; O'Leary, S.T.; Limaye, R.J.; Salmon, D.A. The state of vaccine safety science: systematic reviews of the evidence. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20, e80–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, M.E. Overview of Myocarditis and Pericarditis: ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force, June 23 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mevorach, D.; Anis, E.; Cedar, N.; Bromberg, M.; Haas, E.J.; Nadir, E.; Olsha-Castell, S.; Arad, D.; Hasin, T.; Levi, N.; et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymans, S.; Cooper, L.T. Myocarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination: clinical observations and potential mechanisms. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2022, 19, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.A.; Tingle, A.J.; MacWilliam, L.; Horne, C.; Keown, P.; Gaur, L.K.; Nepom, G.T. HLA-DR class II associations with rubella vaccine-induced joint manifestations. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1998, 177, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiak, M.; Zawadzka-Starczewska, K.; Lewiński, A. Significance of HLA Haplotypes in Two Patients with Subacute Thyroiditis Triggered by mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, 10, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolze, A.; Mogensen, T.H.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Abel, L.; Andreakos, E.; Arkin, L.M.; Borghesi, A.; Brodin, P.; Hagin, D.; Novelli, G. Decoding the Human Genetic and Immunological Basis of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis. Journal of Clinical Immunology 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.; Ferguson, I.D.; Lewis, P.; Jaggi, P.; Gagliardo, C.; Collins, J.S.; Shaughnessya, R.; Carona, R.; Fuss, C.; Corbin, K.J.E. Symptomatic acute myocarditis in seven adolescents following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination. Pediatrics 2021, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, C.M.; Genovese, L.; Tehrani, B.N.; Atkins, M.; Bakhshi, H.; Chaudhri, S.; Damluji, A.A.; de Lemos, J.A.; Desai, S.S.; Emaminia, A.; et al. Myocarditis Temporally Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination. Circulation 2021, 144, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, E.; Aurigemma, G.; Saucedo, J.; Gerson, D.S. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Radiol Case Rep 2021, 16, 2142–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voleti, N.; Reddy, S.P.; Ssentongo, P. Myocarditis in SARS-CoV-2 infection vs. COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 951314–951314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Kamat, I.; Hotez, P.J. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2021, 144, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Pabani, U.K.; Gul, A.; Muhammad, S.A.; Yousif, Y.; Abumedian, M.; Elmahdi, O.; Gupta, A. COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis: A Systemic Review and Literature Search. Cureus 2022, 14, e27408–e27408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooling, K.; Marin, M.; Wallace, M.; McClung, N.; Chamberland, M.; Lee, G.M.; Talbot, H.K.; Romero, J.R.; Bell, B.P.; Oliver, S.E. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Updated Interim Recommendation for Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 69, 1657–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondiaux, E.; Parisot, P.; Redheuil, A.; Tzaroukian, L.; Levy, Y.; Sileo, C.; Schnuriger, A.; Lorrot, M.; Guedj, R.; Ducou le Pointe, H. Cardiac MRI in Children with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated with COVID-19. Radiology 2020, 297, E283–E288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafil, T.S.; Tzemos, N. Myocarditis in 2020: Advancements in Imaging and Clinical Management. JACC Case Rep 2020, 2, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandeep, N.; Fairchok, M.P.; Hasbani, K. Myocarditis After COVID‐19 Vaccination in Pediatrics: A Proposed Pathway for Triage and Treatment. Journal of the American Heart Association 2022, 11, e026097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okor, I.; Sleem, A.; Zhang, A.; Kadakia, R.; Bob-Manuel, T.; Krim, S.R. Suspected COVID-19-Induced Myopericarditis. Ochsner J 2021, 21, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Panda, P.; Sharma, Y.P.; Handa, N. COVID-19 presenting as acute pericarditis. BMJ Case Reports 2022, 15, e243768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, W.A.M.; Ahmed, A.S.M.; Eljack, M.M.F.; Abbasher Hussien Mohamed Ahmed, K.; S. Haroun, M.; Abdelrahim Abdalla, Y. Acute pericarditis complicated with pericardial effusion as first presentation of COVID-19 in an adult sudanese patient: A case report. Clinical Case Reports 2022, 10, e05570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, L.; Abed El Khaleq, Y.; Storrar, W.; Scheuermann-Freestone, M. COVID-19 myopericarditis with cardiac tamponade in the absence of respiratory symptoms: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2021, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariyanna, P.T.; Sabih, A.; Sutarjono, B.; Shah, K.; Peláez, A.V.; Lewis, J.; Yu, R.; Grewal, E.S.; Jayarangaiah, A.; Das, S. A Systematic Review of COVID-19 and Pericarditis. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, Y.; Charron, P.; Imazio, M.; Badano, L.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Bogaert, J.; Brucato, A.; Gueret, P.; Klingel, K.; Lionis, C.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal 2015, 36, 2921–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Lu, L.; Cao, W.; Li, T. Hypothesis for potential pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection–a review of immune changes in patients with viral pneumonia. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2020, 9, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermani-Alghoraishi, M.; Pouramini, A.; Kafi, F.; Khosravi, A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and severe pericardial effusion: from pathogenesis to management: a case report based systematic review. Current Problems in Cardiology 2021, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, U.; Schumann, C.; Schmidt, K. Current aspects of colchicine therapy--classical indications and new therapeutic uses. European journal of medical research 2001, 6, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Molad, Y. Update on colchicine and its mechanism of action. Current rheumatology reports 2002, 4, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, S.; Huang, S.; Liu, F.; Shao, W.; Mei, K.; Ma, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhu, W.; et al. Prevalence of NSAID use among people with COVID-19 and the association with COVID-19-related outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2022, 88, 5113–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadeniz, H.; Yamak, B.A.; Ozger, H.S.; Sezenoz, B.; Tufan, A.; Emmi, G. Anakinra for the Treatment of COVID-19-Associated Pericarditis: A Case Report. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2020, 34, 883–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazio, M.; Brucato, A.; Lazaros, G.; Andreis, A.; Scarsi, M.; Klein, A.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Adler, Y. Anti-inflammatory therapies for pericardial diseases in the COVID-19 pandemic: safety and potentiality. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2020, 21, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Roper, M.H.; Sperling, L.; Schieber, R.A.; Heffelfinger, J.D.; Casey, C.G.; Miller, J.W.; Santibanez, S.; Herwaldt, B.; Hightower, P. Myocarditis, pericarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy after smallpox vaccination among civilians in the United States, January–October 2003. Clinical infectious diseases 2008, 46, S242–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntz, J.; Crane, B.; Weinmann, S.; Naleway, A.L.; Vaccine Safety Datalink Investigator, T. Myocarditis and pericarditis are rare following live viral vaccinations in adults. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ebrahim, E.K.; Algazzar, A.; Qutub, M. Reactive Pericarditis post Meningococcal Vaccine: First Case Report in the Literature. International Journal of Cardiovascular Sciences 2020, 34, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishay, Y.; Kenig, A.; Tsemach-Toren, T.; Amer, R.; Rubin, L.; Hershkovitz, Y.; Kharouf, F. Autoimmune phenomena following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 99, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, F.; Cerasuolo, P.G.; Bosello, S.L.; Verardi, L.; Fiori, E.; Cocciolillo, F.; Merlino, B.; Zoli, A.; D'Agostino, M.A. Adult-onset Still's disease following COVID-19 vaccination. Lancet Rheumatol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tano, E.; San Martin, S.; Girgis, S.; Martinez-Fernandez, Y.; Sanchez Vegas, C. Perimyocarditis in Adolescents After Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, J.W.; Wallace, M.; Hadler, S.C.; Langley, G.; Su, J.R.; Oster, M.E.; Broder, K.R.; Gee, J.; Weintraub, E.; Shimabukuro, T. Use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine after reports of myocarditis among vaccine recipients: update from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, June 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2021, 70, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Updated Lake Louise Criteria (2 out of 2) |

Diagnostic Targets |

|---|---|

| Main criteria | |

| T2-based imaging | Myocardial edema |

| Regional* high T2 SI | |

| or | |

| Global T2 SI ratio ≥ 2.0† in T2WI CMR images | |

| or | |

| Regional or global increase in myocardial T2 relaxation time† | |

| T1-based imaging | ↑ T1: Edema (intra-or extracellular), hyperemia/capillary leak, necrosis, fibrosis LGE: Necrosis, fibrosis, (acute extracellular edema) ↑ ECV: Edema (extracellular), hyperemia/capillary leak, necrosis, fibrosis |

| Regional or global increase of native myocardial T1 relaxation time or ECV†, ‡ | |

| or | |

| Areas with high SI in a nonischemic distribution pattern in LGE images | |

| Supportive criteria | |

| Pericardial effusion in cine CMR images | Pericardial inflammation |

| or | |

| High signal intensity of the pericardium in LGE images, T1-mapping or T2-mapping | |

| or | |

| T1 mapping or T2 mapping | |

| Systolic LV wall motion abnormality in cine CMR images | LV dysfunction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).