1. Background

Globally, cyberbullying has become one of the leading forms of bullying in the workplace, schools and on the playing fields [

1,

2,

3]. Heiman and Olenik-Shemesh describe cyberbullying as a ‘negative activity aimed at deliberate and repeated harm through the use of a variety of electronic media’ [

4]. Nocentini et al., further discussed cyberbullying as three distinct characteristics : anonymity, flaming and public vs. private [

5]. Anonymity is when the bully makes sure that they do not reveal themselves and takes extreme measures to hide their identity from others by hiding behind an electronic device (e.g. a cellphone) while harassing and intimidating other people anonymously. Flaming occurs when the victim is known by the perpetrator (intentionally) and chooses to ridicule them publicly to gain popularity or ‘likes’ from observers. The public vs. private characteristic of cyberbullying occurs when the bully uses public or private forums, for example a webpage or email to victimize other people, with the intention of shaming or causing harm to the person. Eden, Heiman and Olenik-Shemesh pointed out that incidences of cyberbullying often occurs in online ‘chat rooms’, small text messaging (SMS), email and voting booths [

6]. Menesini and Nocentini state that the aspects of conventional bullying such as power imbalance, intentionality and repetition is evident in most cases of cyberbullying [

7]. Power imbalance between the perpetrator and the victim is another characteristic of cyberbullying, as it increases the likelihood of the severity of the bullying (i.e., physical, verbal, social and cyberbullying).

Literature show that cyberbullying has devastating effects on victims [

3,

8]. In particular, Obrien and Moules found a strong positive correlation between cyberbullying and depression, anxiety and self-harming behaviours among participants [

9]. Similarly, a multi-country study conducted by Wright et al., in China, India and Japan found that some of the teenagers who experienced cyberbullying reported low levels of peer attachments, self-esteem and confidence [

10]. Recent literature show the emergence of COVID-19 and restrictions imposed by countries to curb the spread of the virus by confining people to their homes in 2019 and 2020 also meant many activities such as work and learning moved to online format, thus increasing incidences of cyberbullying [

11,

12,

13].

Over the years, there have been evidence suggesting cyberbullying is emerging in educational institutions [

14]. A study undertaken in Malawi schools found 50% of 2, 264 school learners reported being bullied by their peers [

15]. The learners being bullied learners ended up resorting to negative coping strategies such as substance abuse and withdrawing from their peers in the school. Similarly, Farhangpour et al., reported 52% of Grade 8’s in a Cape Town school were being bullied, while 36.3% of learners in grade 8 and 11 in a Durban school were found to be suffering from the aftereffects of cyberbullying [

16]. The majority of the learners in schools are poorly equipped to defend themselves from cyberbullies. This means that educators need to be adequately equipped with training and knowledge on how to manage cases of cyberbullying in schools.

In 2019, South Africa did not have any laws/policies specific to e-safety and cyberbullying to help schools prevent and manage cases of cyberbullying amongst learners. Instead, educators had to rely on the ubiquitous South African School Act No. 84 of 1996 and Children’s Act No. 38 of 2005 to address learner-related conflicts in schools. The School Act 84 of 1996 lists a set of rules for learner behaviour and discipline through mutual respect. The Act further outlines how learner misbehaviour must be dealt with using the Act and the school code of conduct. Furthermore, the Children's Act 38 of 2005 focuses on the protection of children against abuse, neglect, maltreatment and promotes the best interest of the child [

17]. Any form of bullying is regarded as abuse and although these Acts are not explicit about steps to be taken by educators when confronted with cases of cyberbullying, they remain reliable and valuable legal instruments to discipline perpetuators of this type of abuse.

In light of the prevalence of cyberbullying in school settings, the researchers sought to explore educators’ knowledge of cyberbullying and the intervention strategies they have put in place in response to incidences of bullying. It was anticipated that these findings will help inform other educators and social services workers about this form of bullying and encourage them to develop context-specific interventions strategies to deal with the problem.

2. Theoretical Framework

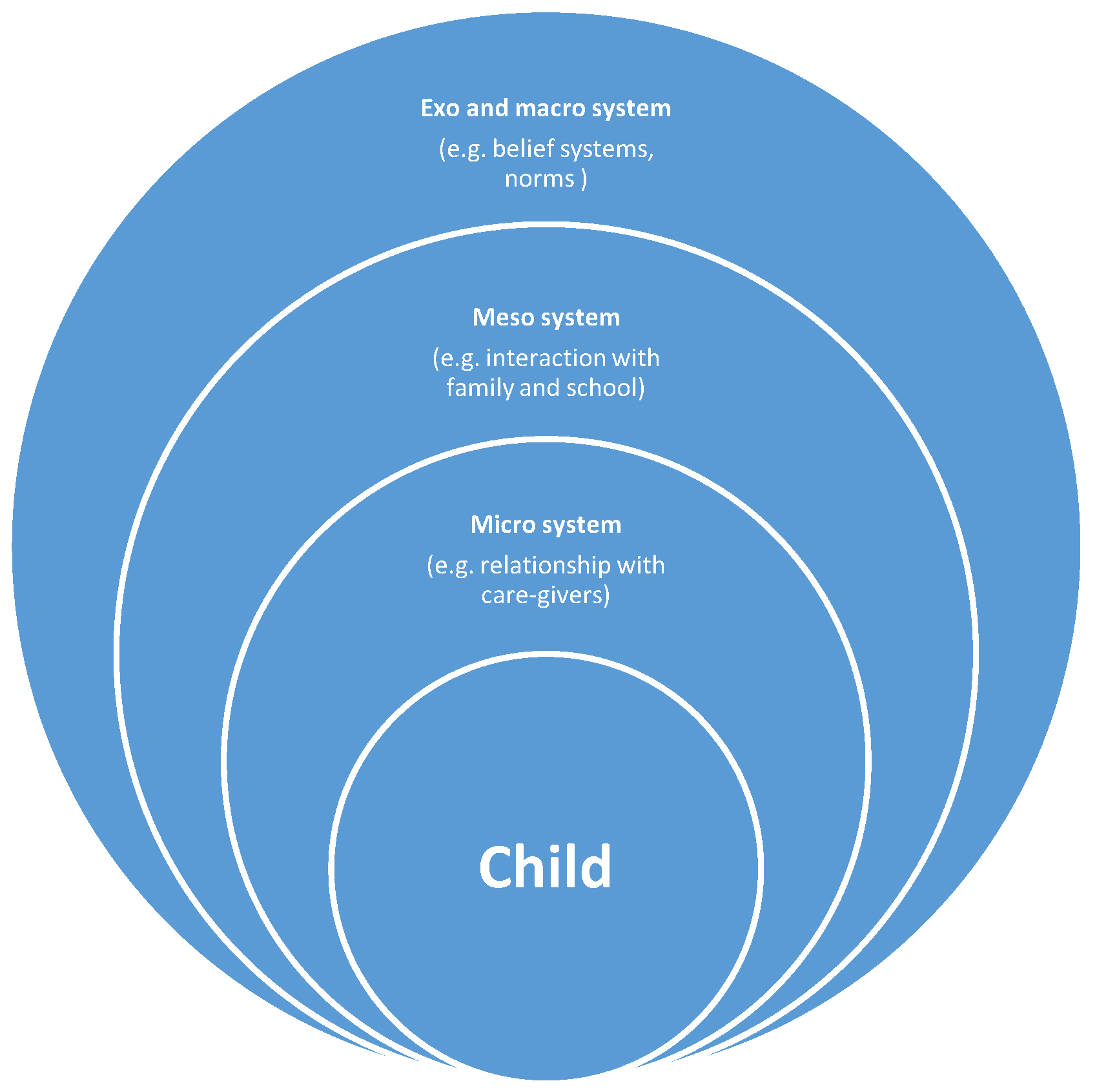

The research was guided by the Ecological Theory. Bronfenbrenner (1980) understands that children are in the centre of a broader system and their interaction with the systems shapes their behaviour [

18]. Within the ecological environment, there are various factors that influence child’s behaviour such as child’s age, impulsivity, defiance, attitudes and exposure to bullying affect other systems they interact with [

18,

19]. In the context of the research, the theory looks at five unique and interrelated systems 1) child, 2) microsystem 3) mesosystem 4) exosystem and 5) macrosystem (see

Figure 1). These systems are significant in understanding the prevalence of socio-economic issues such as bullying, domestic violence, substance abuse etc.

A child’s microsystem involves the relationship that children form with their caregivers, educators and friends [

19]. Studies have shown children’s development is influenced by significant others such as caregivers, educators and friends, and the influence can be positive or detrimental to their development [

20]. For example, parental disengagement/lack of attachment or lack of knowledge around issues of cyberbullying may result in mischievous behaviours, which could include bullying by children.

The mesosystem is the connection between two or more microsystems [

19]. When a child enters the schooling system, the child becomes the primary link between their family and school [

20,

21]. In support of their education, parents often need to communicate with educators and vice versa. Studies have shown lack of parental involvement in children’s education contributes to children/learners poor academic performance and leads to an increase in mischievous behaviours including cyberbullying of other learners [

20,

21,

22].

The exosystem is the environment that the child is not directly located but they have indirect interaction with [

19,

20]. A caregiver’s professional working hours may have detrimental effect on a child, particularly when the caregiver is regularly absent due to long working hours. Consequently, a child who has limited parental or caregiver supervision may be tempted to engage in cyberbullying.

Lastly, the macrosystem focuses on the dominant belief systems, culture and norms that the child learn from the community and broader society [

22]. Children who come from a violent neighbourhood tend to display some of the same bullying behaviours due to the absence of positive role models.

The Ecological Theory enabled the researchers to explore cyberbullying in schools, and how different role-players (i.e. parents and educators) can play a role in addressing it. For example – when parents limit their children access to cellphones for leisure and educators putting in place support systems at school level to ensure both the perpetrator of bullying and victims receives support.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1. Research approach

We made use of a qualitative approach to explore the extent of secondary (FET) educators’ knowledge of cyberbullying as well as their intervention strategies used in a secondary school setting. Aspers and Corte describe qualitative research as a method based upon the need to understand the experiences and perceptions of participants regarding a particular phenomenon [

23]. This approach was suitable to the focus of this study as it created an opportunity for the researchers to engage at a deeper level with each of the educators about their experiences, knowledge and perceptions of cyberbullying in a school setting, and what they doing to prevent and manage this unpleasant social issue.

3.2. Study setting, population and sample

The participants were recruited from a private secondary school located in Johannesburg, South Africa. Purposive sampling technique was used to recruit eight experienced secondary (FET) educators to share their insights on cyberbullying (see

Table 1). Etikan and Bala describe purposive sampling as a technique that allows researchers to select participants based on the desired characteristics (e.g. age and work experience) [

24].

Table 1 present the participants’ characteristics.

3.3. Data collection and analysis method

We collected data from semi-structured one-on-one interviews. The interview questions explored the educators’ experiences and perceptions of cyberbullying, contributing factors, strategies they have put in place to respond to cases of cyberbullying. The interviews were conducted in English, with each interview lasting approximately 45 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded with each participant’s consent. To analyse the data, the researchers made use of thematic analysis method as described by Braun [

25]. The audio files were transcribed verbatim, the researchers then coded transcripts line-by-line to identify emergent themes in line with the study objectives (see

Table 2).

4. Findings

The findings are presented using the study objectives namely:

(1) to explore educators’ knowledge of cyberbullying among learners,

(2) to identify educators’ intervention strategies aimed at addressing cyberbullying and

(3) to identify the challenges faced by educators when implementing the intervention strategies (see

Table 2).

5. To explore educators’ understandings of cyberbullying among learners

Three themes emerged from this objective:

1.1 cyberbullying as an online event,

1.2 asynchronous and anonymous communication and

1.3 cyberbullying causes harm.

6. Cyberbullying as an online event

The majority of the educators agreed that cyberbullying occurs through online communication medium such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. This theme was captured when the educators said:

“So, the idea is that cyber-bullying is around bullying a student through the use of internet, messaging or technology over computers, Wi-Fi, that kind of thing” (Educator 7).

Over the years, the advancement of computer technology in South Africa mean that many people have gained access to these communication platforms. This explains why this type of bullying is occurring in almost all the communication platforms as alluded by the educators. There were some educators who highlighted there is a distance between the cyberbully and the one being bullied.

7. Asynchronous and anonymous bullying

Cyberbullying happens at a distance where there is a screen instead of face-to-face or direct human interaction. The lack of direct engagement encourages the bully to continue with the abuse, harassment and intimidation of the other person. In addition, anonymity often means that he or she is less likely to be identified and held accountable. This theme was captured when the educators said:

“It’s not the full contact. You are not seeing the person. You know kids are embolden in their private space to be harmful. So, I think the soft approach of it. The way access of doing it” (educator 2).

and

“Cyberbullying is the protection of a screen. So instead of a shield in front of you, people use the distance that even social media, for example, can create” (Educator 3).

Furthermore, Educator 3 argued the cyberbullies uses technological device such as a cellphone to anonymously initiate contact with their victims and harass them. As a result, the bullies feel protected while they interact with their victims.

“People can log on with pseudo accounts or ghost accounts and create a lot of havoc without having to be held accountable” (Educator 3).

From the above participant’s account, it is evident cyberbullying is worsened by the asynchronous and anonymous communication between perpetrators and victims. The perpetrators find the courage to initiate and continue with the abuse of their victims due to the perceived absence of accountability created by online interaction. Other educators mentioned some bullies created pseudo online accounts to bully their victims.

8. Cyberbullying causes harm

The educators agreed that cyberbullying is harmful as it often involves the use of insensitive and vulgar language, which could have detrimental effects on victims’ mental health. The intention of the cyberbully is to hurt and humiliate their victims.

“It [cyberbullying] is any kind of behaviour, whether it’s something written down, something posted, that causes emotional or psychological harm to the person at whom the message is intended” (Educator 5).

Other educators elaborated that cyberbullying is worse than physical bullying as this type of bullying leave victims with emotional scars, and unless the victim speaks out it is difficult to know that they are being bullied and in need of support.

“The harmful nature of it [cyberbullying] is probably worse than the physical bullying – in my experience” (Educator 2).

In the next section of the paper, we highlight some of the steps taken by the educators to respond to cases of bullying the school.

9. To identify educators’ strategies aimed at preventing and managing cyberbullying

In relation to this objective, four themes emerged: (1) evidence collection, (2) disciplinary processes, (3) Grade Controllers and (4) monitoring systems.

10. Intervention strategy: evidence collection

Before the perpetrator can be charged, educators are expected to collect evidence for use. The evidence gathered is used to charge and initiate disciplinary process against the perpetrator of the abuse.

“Typically, what happens in a case of cyberbullying, is there has to be evidence. That is always key because a child can come to us and say: “Ah, I was bullied”, but where is the evidence of it? We cannot go to somebody and say, “You bullied this child” if there is no evidence of it” (Educator 7).

However, the educators contended it is not always possible to gather information about bullying, as it often occurs in a private space such as personal communication over the phone. Furthermore, the victim in the ‘complaint-registering phase’ may be asked to provide the evidence. The evidence could take different forms, if the bullying occurred in a platform such as on Facebook where he or she may have to provide screenshot of the offensive communication.

“They (complainant) need to keep a ‘screenshot’ or thread of the conversation or what’s happening on Facebook” (Educator 7).

The collected evidence is then able to be used as part of disciplinary hearing that will be initiated following a formal complaint/investigation.

11. Intervention strategy: disciplinary processes

The school has established a committee that handles learner related conduct, cases of bullying are also handled by the committee. Once evidence of the bullying has been collected, a disciplinary process is initiated by the school. This theme was captured when the educators said:

“We have a committee that deals with learners’ discipline. We have a gentleman who deals with boys’ discipline and a lady who deals with girls’ discipline” (Educator 7).

There are procedures to be followed after a learner had laid a complaint of bullying. The procedure entails calling in the affected learners (i.e. the learner alleged to be the bully and the alleged victim) to give their statement/affidavit of the incident. The parties can also be interviewed further to gather additional information about the alleged incident.

“So, we have a formal procedure to go through that. You call the learner in. You get the story. You call the witnesses, you call the bully. You get evidence, and then you make a decision” (Educator 5).

The school also acknowledges bullying can result in emotional hurt on the victims. Therefore, measures have been put in place to provide emotional support to victims.

“The disciplinary process is open on both sides. It also considers the emotional needs of the victim as well as the bully” (Educator 2).

The school had employed an educational psychologist to provide psychosocial support to learners. The study did not establish the role of the psychologist in the prevention and management of cyberbullying in the school.

Furthermore, it is also important to highlight that the school has also made efforts to prevent the occurrence of learners’ misconduct by appointing Grade Controllers. The role of Grade Controllers is to report learner related issues to educators timeously.

12. Intervention strategy: Grade Controllers and monitoring systems

The Grade Controllers are learners appointed in each grade to monitor learning-related challenges in the classroom. Learners experiencing any discomfort such as bullying are encouraged to report to the Grade Controllers who ensure their issues are communicated to relevant educators for assistance.

“The grade controllers intervention does go a long way, because of their closeness and relationship with other learners unlike when it’s a teacher they have to report their case to” (Educator 6).

The educators are of the view that learners are more open about their learning-related challenges to the Grade Controllers.

“when a learner is reluctant to give you any details, for example - they won’t give you names, they won’t give dates, they won’t provide any evidence – that is when I hand over to the Grade Controllers for intervention” (Educator 3).

The Grade Controllers have been empowered by the school management to help the school find solutions to learning issues, especially in cases were the Grade Controllers can negotiate with learners and find solution without educators’ involvement.

“You know we have got processes on how to deal with all these things, so to some effect we get involved and other times we don’t get involved – for some cases I receive I report it to the relevant grade controller so they can take effective action” (Educator 2).

However, the study was not able to establish if the Grade Controllers received training to effectively detect and manage cases of cyberbullying in the classroom. Without dedicated training and support the Grade Controllers may find it difficult to mediate between victims and perpetrators of this form of bullying.

Furthermore, to stop cyberbullying from occurring, educators are part of learners’ WhatsApp groups. Learners in the schools are members of various groups (i.e sport and subject related groups). Educator’s role in the groups is to moderate learners’ behaviour and improve accountability when something goes wrong.

“We have now implemented a rule, any WhatsApp group that has a school name, has to have a educator on it. Because we cannot be held responsible for something we can’t control” (Educator 7).

“…. if there is there is a group of whatever (e.g. soccer boys), and they are WhatsApping each other and it gets out of hand, but there is no educator on that group, how can we be held accountable? We have made a rule now to try and combat that; that if there is any group that has the school name on it, it has to have an educator in there to moderate participant’s behaviour” (Educator 7).

Many learners have access to social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp, it is commendable that the school has found a way to participate in these platforms with the primary goal of moderating learner’s interactions. In next section of the paper, we identify the challenges educators faces in implementing these strategies to curb cyberbullying in the school.

13. To identify the challenges educators faces in implementing the strategies to curb cyberbullying

Three themes emerged in relation to the challenges educators face when implementing the strategies intended to curb cyberbullying in the school: (1) the home context/environment, (2) monitoring and tracking of cyberbullying and (3) …? Mitigating the fear of reprisal.

Challenge 1: uncooperative parents/ lack of collaborative between school and parents

Some educators complained that parents do not want to work with educators to prevent and manage cyberbullying in the school. The educators were concerned parents expect them to be responsible for all areas of their children’s conduct.

“It is not our job to parent other people’s children. We can provide a safe learning space for them, which I think we do. We will take steps to help children if they are feeling fearful or alone or bullied. We can be help in those contexts, but I don’t feel that we are here to replace a parent. At some point a parent has to parent. I think in many cases we are dealing with the consequences of parents not parenting effectively” (Educator 7).

Some of the educators were also concerned that parents defend their children when found to be mischievous thus making it difficult for educators to enforce the school disciplinary rules.

“It does become difficult when parents are unreasonable in their demands and willing to take a bit of responsibility and accountability from their side” (Participant 2).

“When there is a case of bullying, the school phones the parent and says this is what your child has done... in some cases the parent immediately takes their child side… I think that parents are more trying to be mates, friends or fitting in with their children rather than teaching and disciplining them (Educator 6).

“[If] the parents aren't prepared to work with us and check their children’s phones every day, it is not going to be monitored or managed… they are absent parents. You know, they don't care” (Educator 4).

The educators felt the school environment and home environment are not working together which places great strain on the educators as pseudo-parents (in loco parentis) and which decreases the effectiveness of the interventions they have put in place to curb cyberbullying.

“With cyberbullying, learners would say ‘this is my private social media account. It didn’t happen at school’. As an educator what do you if the bullying occurs outside school hours? This gives you an idea of how the school sometimes doesn’t know how to judge the boundary between what happens at school and what happens at home” (Educator 5).

Challenge 2: monitoring and tracking cyberbullying

The educators further explained that it is difficult to monitor and track incidences of cyberbullying in the school, since keeping close eye on learners’ interactions can be regarded as invasion of their privacy.

“Cases are better managed when there is a physical contact, things that are said over WhatsApp or Instagram or which happened at home, there is less we can do. We would need to get a police search warrant from Police in order to search the phone. There are so many limitations” (Educator 3).

The educators explained that they do not have the powers to request to search learners’ cellphones, let alone monitor their private/personal social media accounts. It is easier to identify cases of physical abuse as the victim will normally present with physical markings to show abuse took place.

“The physical abuse you can monitor because the kid will come back and say you know he/she has hit me again, but cyber bullying is – I feel it’s like – to a certain extent not controllable” (Educator 2).

The educators expressed the point that parents do not want to collaborate with the school in identifying and preventing cases of cyberbullying. They felt parents are unfairly delegating part of their parental responsibility, which is to instil discipline, onto them as educators.

Challenge 3: fear of reprisal

Some educators explained some learners in the school do not report cases of cyberbullying as they do not want to get themselves or others in trouble.

“They don’t like being whistle blowers. They don’t like being snitches at all” (Educator 5).

“Learners are reluctant to give the details of bullying, they typically don’t want to get involved. They will tell you the outcome of something which is “some of the girls have been saying mean things about me” and then you go “Well, how did that happen?” and they go “Mmmm”. They want you to deal with the results not the methodology” (Educator 3).

The educators explained that learners believe if they report their experience of cyberbullying to educators or be a witness, it may put them in a place of danger with the bully.

“I think it is a bit of a ‘catch-22’ situation because if they report it, that means we have to go to the perpetrator. The perpetrator is going to know who reported it. So, it is a lot to do with “I’m protecting myself” rather than “we aren’t doing our job properly”. They don’t want to come forward because they are fearful. Some kids are strong enough, they come and talk to us about it” (Educator 7).

It was evident learners’ unwillingness to report cases of cyberbullying to educators or Grade Controllers make it difficult for the school to identify and respond to incidences of cyberbullying in the school. In the next section, the researchers discuss the findings in relation to literature.

14. Discussion and Recommendations

We studied educator’s knowledge of cyberbullying among school learners and the intervention strategies they have put in place to curb this problem. Educators were found to be knowledgeable about the manifestation of cyberbullying and the effects it on victims. This finding is collaborated by literature, Cillers and Chinyamurindi study in Eastern Cape primary and secondary schools found educators to have sufficient knowledge of cyberbullying, particularly how it occurs [

26]. However, some of the educators felt less is being done to elevate the discussions about cyberbullying as one of the issues affecting learners and educators in schools. Scholars argues cyberbullying if not addressed could have detrimental effects on learners in particular, poor grades, low self-esteem and suicidal thoughts [

27]. In the current study, we found educators to be appreciative of knowing about the effects of cyberbullying on learner’s education and taking steps to remedy the problem.

Educators sought more proactive measures to manage cases of cyberbullying. However, the invisible nature of cyberbullying occurrence made it difficult for educators to timeously identify and address cases. In 2020, of the 58.93 million population in South Africa, 22 million people were active on social media platforms such as Facebook and Whatsapp. As a result of the increasing access to social media platforms, instant /near real-time communication is one button click away for many people. Unfortunately, some people as shown by available literature, use social media networking to spread hatred, abuse and harm other users. Furthermore, our participants reported because this type of abuse occurs in closed spaces and often after school hours, it is near impossible for them to track and discipline the perpetrators.

The lack of collaborative between the school and parents was seen as contributing to the spike in incidences of cyberbullying. Parental involvement can help reduce the chance of a child being bullied [

28]. For example – parents/ caregivers can use blocking or filtering software to enable them to monitor how their children interact with others on social media. On the contrary, Hoff and Mitchell explains some parents may not be aware about the prevalence of cyberbullying in schools, as their children hide their experiences due to the fear of losing their privileges (e.g. cellphone) or fear their parents will learn about their own online activity/behaviour [

29]. Furthermore, Rachoene and Oyedemi recommend children should take steps to avoid being bullied by disassociating themselves from known bullies or completely closing their social media accounts to minimise chances of cyberbullied [

30].

Moreover, learners were reported to be not complementing educators’ efforts in addressing cyberbullying. The learners were less interested in reporting or being a witness to a bullying incident. Literature show learners are less likely to report cases of bullying because of educator’s inaction when presented with information about a bullying incidents [

29,

31,

32]. Learners who are witnesses to bullying incidents also do not want to serve as witness in disciplinary committees due to the fear of being a target post the meeting. Hoff and Mitchell study found 65.35% of learners interviewed did not report cases of cyberbullying to school administrators as they believed the abuse would stop on its own without doing anything about it [

29]. This implies educators need to take proactive steps when presented with cases of cyberbullying (i.e. ensure the bullying stop, where the incident was reported by a third party protect their identify and offer continuous protection). Ngidi and Moletsane argue the lack of action by educators when presented with information about bullying could have detrimental effect on victim’s mental health and education outcomes [

33].

The introduction of Grade Controllers enabled victims of bullying to share learning challenges including experiences with cyberbullying with the Grade Controllers. Available literature recommends that learners do not play an active role in identifying and addressing incidences of cyberbullying. Instead, educators have the responsibility of managing incidences of cyberbullying. However, our findings clearly show that learners (through Graded Controllers) are better positioned to detect and report cases of cyberbullying, particularly when learners are reluctant to report the cases to their educators.

COVID-19 had detrimental effects on the education sector, at the height of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, many schools had to pause learning and invested in information technologies to teach remotely. However, the diversion to online teaching also meant learners spend most/more of their time online, thus creating potential spike in the number of cyberbullying incidences [

11,

13]. The South African Department of Basic Education (DBE) needs to equip educators with relevant knowledge and skills required to tackle cyberbullying beyond the classroom. Active cooperation between educators, caregivers, learners and community need to be established and prioritised in tackling bullying in schools. Studies have shown regular discussion between these parties about internet safety is beneficial in fostering learning, improving educational outcomes and address unhealthy social media conduct amongst learners [

34,

35].

15. Conclusions

While the findings are based on a one secondary school in Johannesburg, they offer a valuable glimpse into cyberbullying in schools and experiences of educators trying to tackle this problem. The findings have various implications lead to the following recommendations for educational context/schools, Firstly, there is need for the perpetrators of this type of bullying to be made aware of its effect on the victims. Secondly, the urgent need to ensure educators are properly equipped with knowledge and skills to deal with any form of bullying in schools is urgent. All educational role players (e.g. caregivers, educators and school management) need to work together to address this problem at multi-level of society (e.g. home, community and school).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.B. and H.M.; methodology, T.B. and H.M.; formal analysis, T.B., H.M. and R.P.; data curation, T.B.; writing – original draft preparation, T.B., H.M and R.P.; writing – review and editing, H.M., T.B. and R.P.; supervision, H.M. and R.P.; project administration, T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the submission of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The researchers obtained ethical clearance from the University of the Witwatersrand HREC (non-medical) reference number: SW/19/05/15 and written permission was obtained from the school management to engage the educators.

Informed Consent Statement

Each participant provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and appreciate the educators who formed part of the study and the academic editor Dr Guy Mcilroy at the University of the Witwatersrand for the time he took to critically review and edit the manuscript before submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Selkie, E.M., J. L. Fales, and M.A. Moreno, Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high school–aged adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment. Journal of Adolescent Health 2016, 58, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, C.D. and B. Roberts-Pittman, Cyberbullying among college students: Prevalence and demographic differences. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, M.P. , et al., Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: A scoping review of social media studies. JAMA pediatrics 2015, 169, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiman, T. and D. Olenik-Shemesh, Cyberbullying experience and gender differences among adolescents in different educational settings. Journal of learning disabilities 2015, 48, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A. , et al., Cyberbullying: Labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 2010, 20, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, S., T. Heiman, and D. Olenik-Shemesh, Teachers’ perceptions, beliefs and concerns about cyberbullying. British journal of educational technology 2013, 44, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E. and A. Nocentini, Cyberbullying definition and measurement: Some critical considerations. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 2009, 217, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, C.L. , Current perspectives: the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics 2014, 5, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, N. and T. Moules, The impact of cyber-bullying on young people’s mental health. 2010.

- Wright, M.F. , et al., Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015, 5, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P. , et al., Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Social Psychology 2021, 161, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y. and Y.-J. Choi, Comparison of Cyberbullying before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utemissova, G.U., S. Danna, and V. N. Nikolaevna, Cyberbullying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Journal of Guidance and Counseling in Schools: Current Perspectives 2021, 11, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cantone, E. , et al., Interventions on bullying and cyberbullying in schools: A systematic review. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH 2015, 11 (Suppl 1 M4). [Google Scholar]

- Kubwalo, H. , et al., Prevalence and correlates of being bullied among in-school adolescents in Malawi: results from the 2009 Global School-Based Health Survey. Malawi Medical Journal 2013, 25, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farhangpour, P., H. N. Mutshaeni, and C. Maluleke, Emotional and academic effects of cyberbullying on students in a rural high school in the Limpopo province, South Africa. South African Journal of Information Management 2019, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.J. , Advancing the Interests of South Africa's Children: A Look at the Best Interests of Children Under South Africa's Children's Act. Mich. St. U. Coll. LJ Int'l L. 2010, 19, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Härkönen, U. , The Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory of human development. 2001.

- Ryan, D.P.J. , Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Retrieved 01, 9 2012. 20 January.

- Lee, C.-H. , An ecological systems approach to bullying behaviors among middle school students in the United States. Journal of interpersonal violence 2011, 26, 1664–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.S. and D.L. Espelage, A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and violent behavior 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, D.U. , et al., A review of research on school bullying among African American youth: an ecological systems analysis. Educational Psychology Review 2013, 25, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, P. and U. Corte, What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative sociology 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I. and K. Bala, Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal 2017, 5, 00149. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. and V. Clarke, Thematic analysis. 2012.

- Cilliers, L. and W. Chinyamurindi, Perceptions of cyber bullying in primary and secondary schools among student teachers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 2020, 86, e12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabvurira, V. and D. Machimbidza, Cyberbullying among high school learners in Zimbabwe: Motives and effects. African Journal of Social Work 2022, 12, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K.L. , Cyberbullying: A preliminary assessment for school personnel. Psychology in the Schools 2008, 45, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, D.L. and S.N. Mitchell, Cyberbullying: Causes, effects, and remedies. Journal of Educational Administration 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachoene, M. and T. Oyedemi, From self-expression to social aggression: Cyberbullying culture among South African youth on Facebook. Communicatio 2015, 41, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekkes, M., F. I. Pijpers, and S.P. Verloove-Vanhorick, Bullying: Who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health education research 2005, 20, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustin, D.H., G. N. Zulu, and A. Basson, Bullying among secondary school learners in South Africa with specific emphasis on cyber bullying. Child Abuse Research in South Africa 2014, 15, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ngidi, N.D. and R. Moletsane, Bullying in school toilets: Experiences of secondary school learners in a South African township. South African Journal of Education 2018, 38 (Supplement 1), s1–s8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbert, J.B., D. Schultz, and L.M. Crothers, Bullying Prevention and the Parent Involvement Model. Journal of School Counseling 2014, 12, n7. [Google Scholar]

- Axford, N. , et al., Involving parents in school-based programmes to prevent and reduce bullying: What effect does it have? Journal of Children's Services.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).