1. Introduction

The deadly and infectious coronavirus 2019 disease (known as COVID-19) brought the world to a standstill; caused stagnancy in all areas of life, including education [

1,

2]. Following the outbreak of COVID-19, Pakistan and many other countries urgently closed all educational institutes and suspended classes to prevent the spread of the disease. This massive and unexpected closure of educational institutes across the globe resulted in a stressful event for most of the stakeholders and became a top priority for institutions to quickly transition their traditional classes to online or virtual modes through cloud campuses, the media, or other digital learning environments [

3]. These rapid moves led to the testing and adoption of remote and technology-driven environments on an unprecedented scale and, as a result, opened several new avenues for teaching, such as mobile teaching (or the same in this study as teaching via mobile technology [

4,

5,

6].

While teachers from developed countries might find it easier to deploy or implement remote teaching arrangements to provide virtual learning opportunities; however, in developing countries contexts, the sudden change posed unprecedented challenges to teachers who are otherwise prone to typical teaching situations – (characterized by formal lecturing in a classroom setting) – and they are not familiar with the needs of modern education and the methods of technology integration in education. One such challenge, for example, surrounds teachers as they attempt to teach remotely on digital platforms whereby, they were confronted with the need to make a complex set of pedagogical decisions on the fly and to grapple with technological issues by rapidly adapting, consolidating, and/or embracing digital systems to offer alternative learning arenas [

7,

8].

Nevertheless, the widespread presence of technology and collective reactions from different actors in administrative positions, politicians, social media, and parents led the teachers to replace their conventional approaches and participate in ICT didactic innovations (especially mobile technology) to keep education running.

The attempt of this study is to provide additional perspectives on teachers’ experiences of the utilization of mobile technology, as an alternative teaching arena, to provide access to and continuation of education during the precarious times of the COVID-19 crisis in Pakistan. This study will be significant to inform authorities to investigate the experiences of teachers leveraging mobile technology to achieve teaching goals in emerging teaching conditions and to generate critical discourse for envisioning (mobile) pedagogy to deliver and augment education under normal conditions.

2. Mobile Learning Technology: An Unavoidable Switch

Mobile learning (or m-learning) refers to a “…learning strategy that supports the mobility of learners, as it facilitates learning at any time and place via the use of mobile devices” [

15,

16]. [

17] defined mobile learning as “…utilizing the ubiquity and unique capabilities of mobile devices, allowing teaching and learning to extend to spaces beyond the traditional classroom.” These definitions and discourse point to the emergence of a new teaching and learning modality to extend education beyond the physical confines of the classroom and that allows teachers to create new kinds of learning experiences and community learning ecosystems beyond the fixed time periods of the school day.

Existing studies in the broader literature have recognized the place and value of mobile learning in education settings; however, there is limited research conducted on whether mobile learning technologies build resilience into teachers’ pedagogy and whether they provide teachers with alternative pedagogical possibilities during the exceptional circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. The evidence [

9] shows that most teachers promptly tap into mobile technology, serving as a potential substitute for face-to-face teaching, amidst socially distanced, unpredictable, and emotionally charged circumstances. This rapid migration to mobile technology skyrocketed because of its potential and affordances that echo to quickly maintain a somewhat reasonable level of instructional continuity - anytime, anywhere – to better fit the education narrative in the face of the pandemic and as a digital response to fight against the COVID-19. Nevertheless, many questions arise about how teachers could capitalize on mobile technology and can produce engaging lessons.

The COVID-19 crisis, however, opened a state of exception that enabled teachers to utilize their mobile devices for continuing education delivery as quickly as possible, without the benefits of the usual planning time, appropriate resources, and pedagogical structure - needed to enrich this way of education [

10,

11,

12]. Such evidence evoked fear that mobile-mediated education amidst COVID-19 may offer quick fixes but not be as effective as face-to-face education [

13]. Arguably the evolution in teaching modalities, created by COVID-19, has had a high impact on the way teachers approach teaching and the creation of such modalities requires teachers to have modern (digital) pedagogical capabilities to meaningfully facilitate teaching and learning [

14]. Given that the "on the fly" circumstances present a nice window to look at ways teachers deal with the need to be flexible and resilient. For this reason, teachers’ utilization of mobile learning technologies to maintain education amidst COVID-19 has been chosen as the focus of this paper.

3. Theoretical Framework

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, various educational institutes opted to cancel all face-to-face classes and immediately started delivering education through remote teaching arrangements. Whilst remote teaching practices have been occurring for many years now, however, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted an emergency transition which is termed “emergency remote teaching (ERT)” [

12,

18]. Divergent to the experiences that are planned, [

12] defines ERT as a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate mode of delivery in critical situations like COVID-19. It encompasses the use of various fully remote teaching solutions that utilize alternative instructional methods such as online/hybrid/mobile-based, audio/visual, and internet-based courses to continue education in crisis circumstances. Such remote teaching options are put in place to provide quick access to education as [

12] terms ‘creative problem solving’, not to create a robust education system.

Regardless of their level of preparedness, the crisis event that resulted in a transition to remote and mobile teaching options - whether it be through asynchronous or synchronous modes - has been challenging for novice teachers because it requires substantial changes in pedagogical strategies, content, and context to get full credit of remote and mobile learning technologies. This unsettledness makes the teachers more hesitant to uptake or deploy mobile technology for crisis response teaching [

19] due largely to not possessing the necessary established pedagogical approaches and technological competence. We construe those teachers working within, or outside school inevitably confront crises. They must be effectively trained and ready to respond by re-establishing the pre-crisis capacity of teaching and pedagogical adaptations through comprehensive school crisis and prevention support [

20].

In view of this, the dynamic model of educational effectiveness (DMEE) shares a focus on the complexity of teaching effectiveness that may be affected by a variety of interrelated factors (including student, teacher, school context, and educational policies). Among these factors, teachers’ work is pivotal in that it might affirm the effectiveness of the educational process. For instance, if the teacher is not effective then it would be difficult to achieve student outcomes and excellence. Thus, educational excellence for students is deeply nurtured by quality teachers.

[

21] rightly pointed out that central to effective teaching is what teachers need to know and be able to use technology in education. Similarly, [

22] the case study reported that the use of inappropriate teaching strategies results in ‘depersonalized’ learning and insufficient interaction among students and teachers. It is, therefore, important to consider the contextual factors – social, cultural, and technical – that could be in the shape of resources, administrative support, mobile pedagogies, and technical skills for a successful transition to remote learning environments. Moreover, the massive and sudden move to remote and mobile operations, sparked by COVID-19, invites us to consider crisis response teaching as an opportunity for transformational change and academic innovation. It is, therefore, necessary to develop teachers’ multidimensional competencies required for crisis teaching mediated by mobile technology [

23] and to prepare them for successful navigation in unexpected events [

24].

4. Method

4.1. Design

The present study employed an interpretivist paradigm [

25] to understand how schoolteachers (in Sindh, Pakistan) experience, construct, and what meanings are attributed to their mobile teaching experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak. Under the umbrella of the interpretivist paradigm, a qualitative exploratory design was used to achieve an in-depth understanding of how teachers interpret experiences, responded to, and portray their shared voices on mobile teaching challenges posed by the COVID-19 situation. This design enabled us to gain greater insight and in-depth exploration of the phenomenon from the participants’ perspectives rather than the researchers – insider’s perspective.

4.2. Participant Recruitment

Initially, 20 teachers were purposely selected to share insights and experiences of mobile-based teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, 7 teachers withdrew and 13 agreed to participate in the study. All the teachers were teaching at public and private schools in the Sindh province of Pakistan with no or very little experience in teaching through mobile technology. Before the commencement of the study, all the participants were informed of the research objectives, methods, and possible risks experienced by the participants. In addition, the confidentiality of participants was ensured by using pseudonyms.

Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic information.

4.3. Data Collection

The data were collected through semi-structured individual interviews with the participants. Considering the lockdowns and safety of the participants and researchers, the interviews were conducted online via video conferencing facilities such as WhatsApp, Zoom and Google Meet. These interviews were based on open-ended questions, allowing participants to share their experiences with mobile technology, the challenges they faced, and what is ‘needed’ to make teaching through mobile technology successful. In general, the data were classified into four themed findings, namely, (1) Crisis-response teaching via mobile technology, (2) teacher capacity and pedagogical adaptation to mobile technology, (3) critical factor for mobile teaching with the lens of DMEE, and (4) organizational and national policy support for facilitating mobile teaching strategies. The interview responses were recorded with the participants’ consent which lasted for approximately 30-40 minutes each.

4.3. Data analysis

The collected data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic content analysis [

26]. As a flexible qualitative analysis tool, NVivo-version 12 was used to produce rich and detailed data reports. In doing so, open coding was made before identifying and reviewing key themes. Each theme was examined to gain an in-depth understanding of the participant’s experiences with mobile teaching.

5. Findings and Discussion

The following themes have emerged in this study which are summarized with relevant quotes from the participants.

5.1. Crisis-Response Teaching via Mobile Technology

The sudden transition to mobile or remote teaching is regarded as a necessity rather than a choice. Considering the COVID-19 situation, mobile or remote teaching arrangements were the only option that works in the crisis despite having pros and cons. Among various necessities, teachers delve into these alternative teaching arenas to respond to broken education via the available (mobile) technology and the internet at home or school. This evidence is seen from the interview data with Meh, Yar, Ahm, and Nur. They shared that

“I use my mobile phone with internet access, which I always carry everywhere, to send learning material to my students”.

(Meh#1, Zoom Interview, May 05, 2021)

“The use of mobile devices for learning and development is truly a wise choice. As a teacher, you should consider the fact that there are a rising number of mobile device owners”.

(Yar#2, Zoom Interview, May 05, 2021)

“Technology, especially mobile phones, can surely be one of the solutions to provide and maintain education access to students in crises and emergency situations”.

(Ahm#3, Zoom Interview, May 06, 2021)

“Whether mobile technology is effective or not: it is the only workable solution in COVID-19 situation”.

(Nur#4, Zoom Interview, May 07, 2021)

To make learning available to primary pupils in crises situation, most teachers find teaching through smartphones a good and easy option, as teachers carry their smartphones everywhere and remain more skilled in its use. Some teachers who already used mobile devices in their traditional classrooms are eager to teach through mobile technologies. Interestingly, these teachers are motivated by the students who seem to be technology-friendly in this 21st century. Data from a variety of studies also support the idea that mobile devices have the potential to support teaching and learning. Suki & Suki (2009) assert that mobile devices are intriguing from an educational perspective since they allow several communication channels on one device, are less expensive, have a similar capability to desktops or laptops, and offer wireless access to educational resources.

Different technologies, though, have unique characteristics; however, mobile technologies, such as smartphones and tablets, are now widely used as teaching and learning tools [

25]. They can provide teachers with more innovative ways to deliver instructions from anywhere [

12,

14]. In the COVID-19 situation, teaching through mobile technologies stands out for a variety of reasons, including mobility, ubiquity, adaptability, interaction collaboration, context awareness, and seamlessness [

26,

27,

28]. Due to these distinctive features and affordances, mobile technology has become a viable educational continuity and recovery instrument. In short, mobile technologies could drastically lessen people's reliance on permanent places and have the potential to completely transform how people work and learn.

5.2. Teacher Capacity and Pedagogical Adaptation to Mobile Technology

Alternative teaching arrangements in this global pandemic needed more than ever before, urged teachers to rethink their role, the nature of content to be taught, and the needs of students to facilitate education provision [

24,

27,

28,

29]. Teachers have undergone a variety of mobile teaching experiences and adapted to new methods for facilitating educational access at a very urgent time. These teachers, intrinsically motivated, try to do things to be successful, particularly to be connected with their students during this pandemic. For instance, Meh (interviewee) stated that

“…it is my responsibility as a teacher to continue to explore and implement suitable teaching options to combat Coronavirus time.” Bux (interviewee), therefore, expresses that

“…it is a new experience for me to manage mobile classes. It becomes interesting with some new patterns and adaptations that require students and myself to be better prepared to face the challenges of an ever-changing era.”

On the other hand, the sudden transition to mobile or remote teaching calls for ‘redefining professional identity,’ because most teachers attempt to replicate traditional practices without adequate training [

30]. For instance, some participants believed

“delivering courses with poor instruction can have disastrous consequences on student’s future.” In the participants’ view, gaining knowledge and expertise in technological skills is of prime importance to successfully deliver their instructions through mobile mediums. As Muh (interviewee) explains that

“it is a critical consideration for alternative teaching and learning mechanisms such as mobile teaching that we must be trained to the best of institute capacity with the basic knowledge and skills to operate this service.” Although most of the teachers lack technological skills and proper use of mobile modes, still they seem to embrace

“whether it is effective or not: it is the only workable solution in COVID-19 situation.” The participants in the study stated that gaining knowledge and expertise in technology is critical to delivering quality education through mobile devices. Teachers acknowledge that mobile technology is not necessarily the most effective solution, but it is the only workable solution in the COVID-19 situation.

5.3. Critical Factors for Mobile Teaching with the lense of DMEE

The success of mobile teaching is highly dependent on the willingness, motivation, and commitment of the teachers. According to Rehman (Interviewee), dedication and a strong desire to make alternative teaching methods work is crucial in ensuring the success of mobile teaching, especially during the global pandemic where health risks are a concern. Similarly, Maryam (interviewee) emphasized the importance of intrinsic motivation and willingness, stating that even with technical knowledge, success may not be achieved without the drive to make it work.

Pedagogical knowledge and technical competencies are also crucial in successful mobile teaching. The success of remote teaching is dependent on teachers' TPACK knowledge and skills, and the support received from the management [

44]. However, in the Pakistani context, most teachers lack technological skills due to a lack of proper training or a positive attitude towards technology [

45,

46]. In such cases, access to available resources and training programs is essential for improving the quality of alternative teaching-learning environments for students.

Moreover, the respondents emphasized that monetary support, up-to-date hardware and software, flexible planning time, instructional design support, and funding are essential for the successful implementation and use of technological tools. In conclusion, the success of mobile teaching is attributed to the pedagogical and technical competencies of the teachers, as well as monetary support. Nevertheless, the quality of mobile learning technology in education can be undermined without proper instruction on how to use the technology.

5.4. Organizational and National Policy Support for Facilitating Mobile Teaching Strategies

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the unpreparedness of government and regulatory bodies in Pakistan to provide support and facilities for alternative teaching methods. The shift to remote teaching was sudden and many teachers faced various technical, conceptual, and methodological challenges. Technical challenges included poor internet connectivity and the use of mobile tools, while conceptual and methodological challenges included a lack of understanding of remote teaching processes, unfamiliar mobile learning tools, and difficulties in content delivery and classroom management. As Abdullah (interviewee) elaborates that “because slow internet connectivity and server-side failures created difficulties to interact and engage students”. Likewise, Jacob (interviewee) states that “there is a predetermined schedule of student’s presentations as an assignment which is disrupted when he/she does not have the stable internet at that time.” Aforementioned view is complimented by Sajid (interviewee) as “in 60 minutes’ mobile class, almost 20 minutes of I and my students spend on ‘can you hear me?’ asking a question, students respond: sorry sir I have lost my connection.” The study participants also reported behavioral challenges, including difficulties in maintaining discipline and ensuring student engagement. These challenges highlight the need for explicit policies and guidelines to support teachers in effective mobile teaching. The provision of technical support and staff development can also help overcome some of these challenges, but without proper access to the internet, these resources may be insufficient. Thus, there is a need for government and regulatory bodies to provide more support and resources to ensure the smooth delivery of instruction during remote teaching.

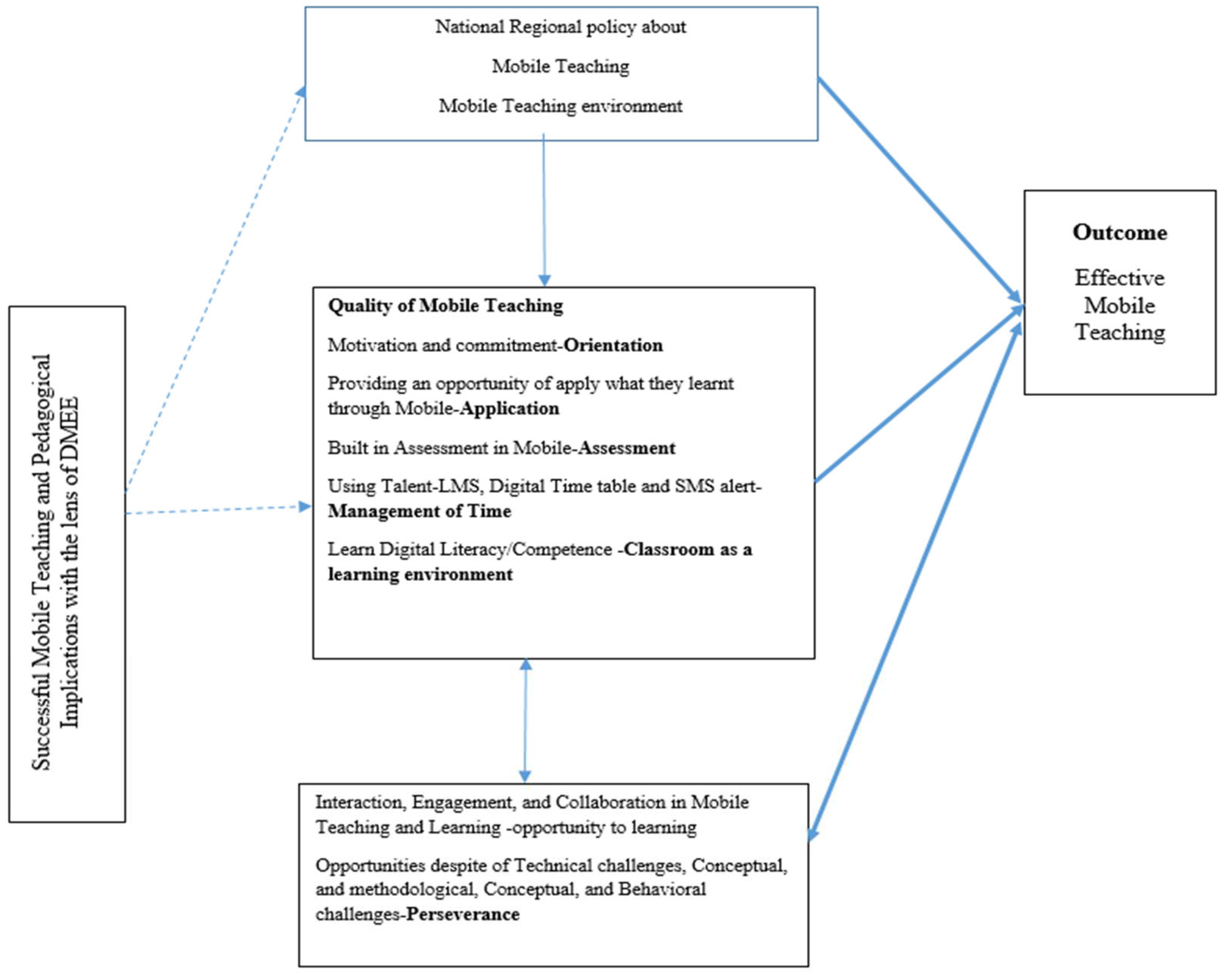

6. Proposed Model for Mobile Teaching with the Lens of DMEE

Based on the findings of the study and collected literature, we are proposing a model for mobile teaching (see

Figure 1) underpinned by the design model for effective educational experience (DMEE). The Design Model for Effective Educational Experience (DMEE) is a comprehensive framework for creating impactful educational experiences. In the context of mobile teaching, it offers a roadmap for designing programs that are both effective and engaging for students. The first step in this process is to clearly define the learning objectives and desired outcomes for students. This ensures that every aspect of the mobile teaching program is aligned with these goals, providing students with a clear sense of purpose and direction. Next, educators must choose appropriate instructional strategies that leverage the unique features of mobile technology. This allows for truly immersive and engaging learning experiences, as students are able to interact with content in new and meaningful ways. Engaging activities that are relevant and designed to promote deep learning are also critical to the success of a mobile teaching program. These activities help to keep students motivated and engaged, ensuring that they are getting the most out of their mobile education journey. The framework also stresses the importance of ongoing assessment, as educators must continuously evaluate the effectiveness of the mobile teaching program and make data-driven decisions to optimize the design. This helps to ensure that students are getting the best possible educational experience. Finally, the mobile teaching program must be launched with confidence, knowing that it has been designed using the DMEE framework and is accessible and usable on a variety of devices and platforms. By taking a student-centric approach and following the DMEE framework, educators can create mobile teaching programs that are truly effective, engaging, and meaningful for learners of all ages and backgrounds.

7. Conclusions and Implications

Our study concludes that the sudden and largely unprepared transition to remote teaching (in our case – mobile teaching) calls for redefining the professional identity of teachers as a necessity rather than a choice - requiring teachers to be responsible for the effective delivery of instructions. This allows us to think that teachers with enough preparation and capacity would not fail to handle students distantly. The findings of the study suggest that the necessary ingredients for successful remote teaching through mobile technology need to be supported with multidimensional factors including professional development opportunities for teachers to develop digital competence/literacies; government and regulatory bodies’ continuous support in providing guidelines and framework; and teachers’ motivation, commitment, and positive attitude towards alternative teaching mechanisms. This study argues that teachers must possess mobile-enabled teaching competencies as they are performing a multi-dimensional role while teaching remotely. Thus, to prepare teachers, a redefined competency-based professional development programme should be designed focusing on developing teachers’ capacity for mobile teaching in areas related to instructional strategies, facilitation, and delivery, sustaining motivation and engagement, and managing technology, and learning resources. Overall, the study and results imply that teacher professional development programmes must equip teachers with the knowledge, tools, and resilience to help them effectively deal with COVID-19 and any uncertain education situation.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impey, C. Coronavirus: social distancing is delaying vital scientific research. Available online: https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-social-distancing-is-delaying-vital-scientific-research-133689 (accessed on 05-10-2021).

- Sun, L.; Tang, Y.; Zuo, W. Coronavirus pushes education online. Nature Materials 2020, 19, 687–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandrić, P.; Hayes, D.; Truelove, I.; Levinson, P.; Mayo, P.; Ryberg, T.; Monzó, L.D.; Allen, Q.; Stewart, P.A.; Carr, P.R. Teaching in the age of Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education 2020, 2, 1069–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikat, S.; Dhillon, J.S.; Wan Ahmad, W.F.; Jamaluddin, R.A.d. A Systematic Review of the Benefits and Challenges of Mobile Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education Sciences 2021, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorghiu, G.; Pribeanu, C.; Lamanauskas, V.; Šlekienė, V. Usefulness of mobile teaching and learning as perceived by Romanian and Lithuanian science teachers. Problems of Education in the 21st Century 2020, 78, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedotun, T.D. Sudden change of pedagogy in education driven by COVID-19: Perspectives and evaluation from a developing country. Research in Globalization 2020, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of educational technology systems 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.N.; Omar, M.N.; Don, Y.; Purnomo, Y.W.; Kasa, M.D. Teachers' Acceptance of Mobile Technology Use towards Innovative Teaching in Malaysian Secondary Schools. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 2022, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlden, S.; Veletsianos, G. Coronavirus pushes universities to switch to online classes–but are they ready. Available online: https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-pushes-universities-to-switch-to-online-classes-but-are-they-ready-132728 (accessed on 05-10-2021).

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital science and education 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review 2020.

- Wang, Z.; Qadir, A.; Asmat, A.; Mian, M.S.A.; Luo, X. The Advent of Coronavirus Disease 2019 and the Impact of Mobile Learning on Student Learning Performance: The Mediating Role of Student Learning Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsakdi, N.; Kortelainen, A.; Veermans, M. The impact of digital pedagogy training on in-service teachers’ attitudes towards digital technologies. Education and Information Technologies 2021, 26, 5041–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Traxler, J. Mobile learning. A handbook for educator and trainers 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.-H.; Wu, Y.-C.J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Kao, H.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Huang, S.-H. Review of trends from mobile learning studies: A meta-analysis. Computers & education 2012, 59, 817–827. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, C.; Vavoula, G.; Glew, J.; Taylor, J.; Sharples, M.; Lefrere, P.; Lonsdale, P.; Naismith, L.; Waycott, J. Guidelines for learning/teaching/tutoring in a mobile environment. 2005. Disponible en:. Acceso en 2012, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.P. COVID-19 and emergency eLearning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemporary Security Policy 2020, 41, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Staying the course: Online education in the United States, 2008; ERIC: 2008.

- Keengwe, J.; Kidd, T.; Kyei-Blankson, L. Faculty and technology: Implications for faculty training and technology leadership. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2009, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers college record 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.; Barnett, J. On-line learning: A quality experience. New review of information networking 2000, 6, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. Journal of Information Technology Education 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane*, K. Integrating face-to-face and online teaching: academics' role concept and teaching choices. Teaching in Higher Education 2004, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research methods for business students; Pearson education: Pearson education, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook; Sage publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, I.; Guasch, T.; Espasa, A. University teacher roles and competencies in online learning environments: a theoretical analysis of teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education 2009, 32, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawane, J.; Spector, J.M. Prioritization of online instructor roles: implications for competency-based teacher education programs. Distance education 2009, 30, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Ritzhaupt, A.; Kumar, S.; Budhrani, K. Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Course design, assessment and evaluation, and facilitation. The Internet and Higher Education 2019, 42, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, P. From face-to-face teaching to online teaching: Pedagogical transitions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings ASCILITE 2011: 28th annual conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education: Changing demands, changing directions; 2011; pp. 1050–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Roddy, C.; Amiet, D.L.; Chung, J.; Holt, C.; Shaw, L.; McKenzie, S.; Garivaldis, F.; Lodge, J.M.; Mundy, M.E. Applying best practice online learning, teaching, and support to intensive online environments: An integrative review. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Education; 2017; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Cornelious, L.F. Preparing instructors for quality online instruction. Online Journal of distance learning administration 2005, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, C.; Barbour, M.; Brown, R.; Diamond, D.; Lowes, S.; Powell, A.; Rose, R.; Scheick, A.; Scribner, D.; Van der Molen, J. Research Committee Issues Brief: Examining Communication and Interaction in Online Teaching. International Association for K-12 Online Learning 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bangert, A. The influence of social presence and teaching presence on the quality of online critical inquiry. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 2008, 20, 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, M.L. Increase Engaged Student Learning Using Google Docs as a Discussion Platform. Teaching & Learning Inquiry 2021, 9, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, A.G.; Mustafa, Y.; Ali, S. Integrating universal design for learning as a pedagogical framework to teach and support all learners in science concepts. International Journal of Innovation in Education 2018, 5, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The internet and higher education 1999, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The internet and higher education 2010, 13, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of distance education 2001, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, P. Reflection as an indicator of cognitive presence. E-Learning and Digital Media 2014, 11, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Beer, M.; Slack, F. E-learning challenges faced by academics in higher education. Journal of Education and Training Studies 2015, 3, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugar, W.; Martindale, T.; Crawley, F.E. One professor’s face-to-face teaching strategies while becoming an online instructor. Quarterly Review of Distance Education 2007, 8, 365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, B.; Ashford-Rowe, K.; Barajas-Murph, N.; Dobbin, G.; Knott, J.; McCormack, M.; Pomerantz, J.; Seilhamer, R.; Weber, N. Horizon report 2019 higher education edition; EDU19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-J.; Bonk, C.J. The future of online teaching and learning in higher education. Educause quarterly 2006, 29, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, I.; Ashraf, F.; Saeed, I.; Shah, K.; Azhar, N.; Anam, W. Teachers’ performance problems in higher education institutions of Pakistan. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Z.A.; Khoja, S.A. Role of ICT in shaping the future of pakistani higher education system. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 2011, 10, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).