2. Materials and Methods

The “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Standards” was adopted to carry out the review [

7]. The research team used secondary sources such as online databases to retrieve conference papers, journal articles, theses, research reports, etc. Multiple searches were performed using themes and phrases related to SD to retrieve the papers. The search covered the economic, social, and environmental spheres of sustainability and the broader goal of sustainable development. Time constraints were not imposed on the search because the significance of the items to the SD conversation was valued more than their age. As much recent literature as possible was incorporated into the study to emphasize the relevance and significance of the subject.

Materials that did not contribute to our understanding of development and sustainability were eliminated. To ensure we didn’t miss anything, we also checked the selected articles’ reference lists for additional resources on our topic of interest. The search was conducted by examining the titles and abstracts of various articles and books. The review included other information if they were relevant to the topic at hand and satisfied other inclusion and exclusion criteria. Customarily, materials needed to meet relevance, authority, and currency standards to be included [

8]. Relevance to the SD debate was evaluated, and the content’s authority was bolstered by its publication in a neutral forum that put it through a thorough review process before it was made public.

On the other hand, currency was measured by how relevant the material was to the current state of the SD debate, as evidenced by things like citations [

8]. From

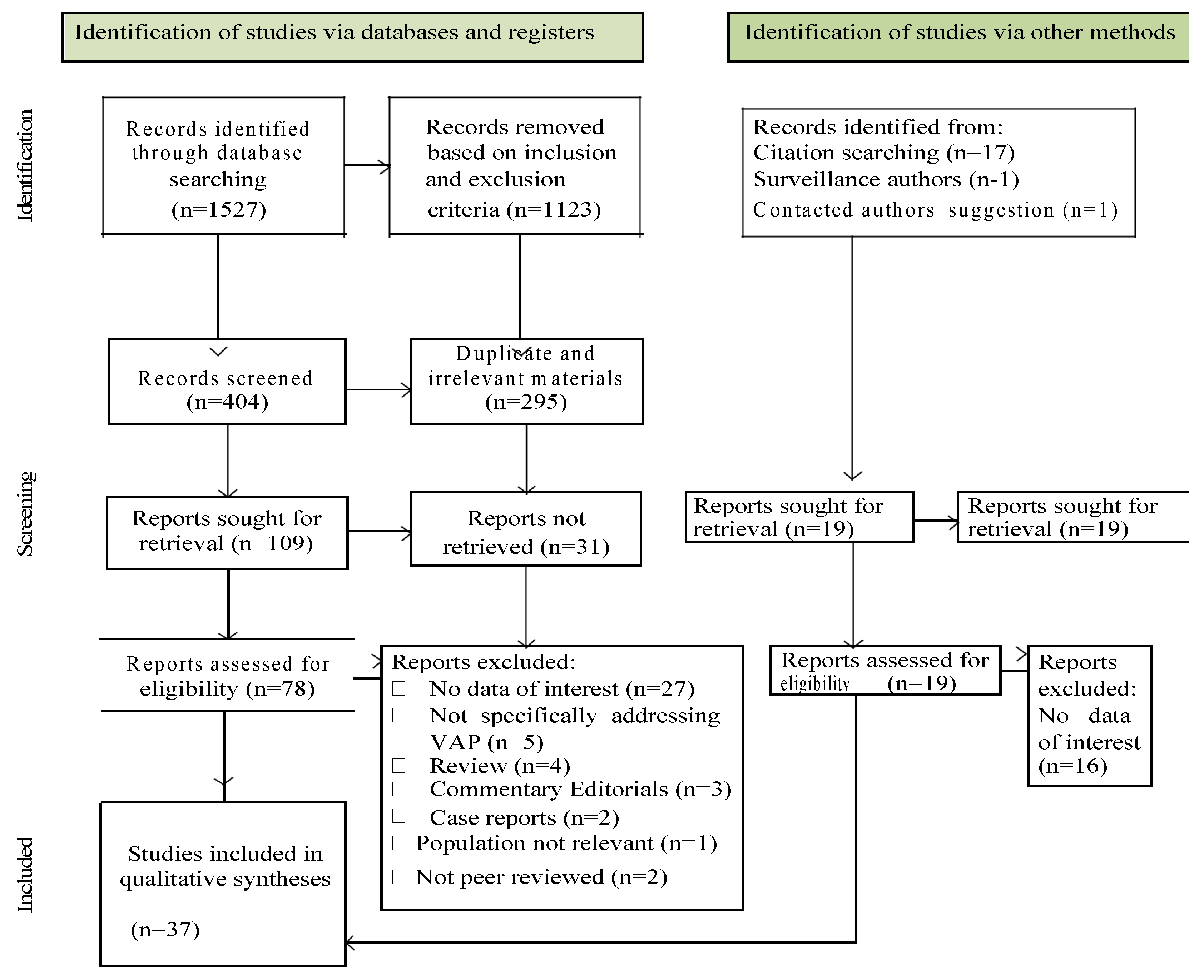

Figure 1, there were 1527 references found using the basic search parameters, and 19 records were also identified via other methods such as citation searching, surveillance, and contacting of authors. However, using the earlier screening and eligibility procedures, 78 articles from basic search parameters and 19 from other methods were eligible for full-text retrieval, as depicted in

Figure 1. Out of that, 34 from basic search parameters and three from other methods matched the final inclusion requirements. Thus, a total of 37 materials were included in the qualitative synthesis.

Relevant information was extracted after a careful inspection of the entire text. Data analysis was performed using a hybrid of the techniques of recursive abstraction [

9] and qualitative content analysis [

10]. Notes, rather than codes, were used to categorize the data; in this case, the relevant details were gradually assembled using the aforementioned keywords. The purpose of the series of summarizing tasks, all completed by hand, was to highlight the most critical findings from each input data source and eliminate any inconsistencies or superfluous details. While compiling each summary result, the reasons for excluding certain data points were recorded. The material was gathered using summaries, then synthesized, connected, and paraphrased to make the information more understandable, brief, coherent, and condensed without losing the original meaning in merging the themes.

Figure 1.

Material Selection algorithm.

Figure 1.

Material Selection algorithm.

The Concept of Sustainability

Technically, sustainability means the capacity to preserve an object, result, or procedure over time [

11]. However, in development literature, most academics, researchers, and practitioners use the term to mean improving and sustaining a healthy economic, ecological, and social system for human development [

4,

12]. Stoddart et al. [

13] opined that Sustainability is the equitable and efficient distribution of resources across different eras and social and economic activities undertaken within the limits of a limited ecosystem. Conversely, Mensah [

5] defines sustainability as an evolving equilibrium in the interactions between the inhabitants and the utilization rate of its surroundings, in which the community evolves to convey its maximum capability without worsening the bearing ability of the environment. According to Thomas [

14], in this view, sustainability stresses choices and their ability to fulfill wishes and preferences without expending available means of production. This offers recommendations about how people should approach their economic and social lives to maximize the ecological resources available for human advancement.

Creating a sustainable society, environment, and economy within the earth’s carrying capacity limits is one of today’s most significant challenges. As reported by Hák, Janouková, & Moldan [

15]. The World Bank [

16] stressed the importance of developing novel approaches to these problems. To back up this assertion, Mensah [

5],) argues that the greatest goal of the idea of sustainability is to encourage the best alignment and equilibrium between social, economic, and the ecosystem, given the existing potential of the earth’s natural systems to regenerate. According to Gossling-Goidsmiths [

17], any proper definition of sustainability must revolve around this kind of ever-evolving harmony and cohesion.

Mensah and Enu-Kwesi [

4] suggested that the terminology should also promote the idea of intergenerational goodwill, which is undoubtedly an integral concept and poses difficulties since it is difficult to define and evaluate the needs of future generations. Consistent with the preceding, transient definitions of sustainability aim to highlight and incorporate economic, ecological, and social frameworks for the long-term benefit of humanity’s management of human challenges [

18]. In this way, financial models aim to amass and employ economic resources sustainably, ecological models prioritize the health of ecosystems and biodiversity, and social models work to strengthen a range of systems (ideological, institutional, wellness, and academic) to ensure that human rights, wellness, and sustainable development are always protected [

19,

20].

3.3. Sustainable Development

According to Kates et al. [

21], numerous researchers have emphasized the need for an impartial definition of SD. Elliott [

22] asserts that definitions are essential for laying the groundwork for the future development of a strategy to achieve SD. Currently, there are numerous interpretations of SD, most based on previous discussions of various global trends and scholarly publications. According to some studies, there are over 200 readily available definitions of SD [

23]. According to Pezzey [

24], the variety of definitions demonstrates that everyone agrees SD is a concept, but no one defines it consistently.

Since it has been connected with various definitions, meanings, and interpretations, “sustainable development” has become the most frequently used term in the development debate. If SD were to be defined literally, it means development that can be maintained for a particular period or forever [

13]. The term is composed of the words “sustainable” and “development” from a structural standpoint. The words “sustainable” and “development,” which are combined to form the concept of SD, have each been defined differently from a variety of perspectives, and the concept of SD itself has been viewed from a variety of perspectives, resulting in a variety of definitions of the concept.

The WCED publication presents a definition of SD that differs from those most commonly employed. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) envisioned an alternative growth that maintained human advancement in less localized areas within a few periods and the whole world in the near future. The alternative was described as “development that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” [

25].

After initial conception, the definition has seen frequent revision, misrepresentation, and alterations [

26], resulting in a rise in excessive arguments, condemnations, and various strategy documents. The most cited responses talk about how monotonous and vague the definition is. Despite this, several studies have demonstrated that this response is typically attributable to the content’s subjective analysis [

26]. Notably, the sections of the document that follow the above-stated definition reveal the complexity and far-reaching of the team’s conception of SD [

26].

The WCED’s effort is explained as a strategy for impeding and valuing the growing skepticism among advancing territories regarding the environmental considerations of advanced countries [

27]. Consequently, the WCED’s publication has been applauded for efficiently incorporating socioeconomic significance into an agenda previously deemed dependent [

28].

Another way to explain SD is to use economic or financial terminology. As a result, Pearce et al. [

29] posited that sustainability is analogous to “non-declining capital”. This notion is expanded by Dresner [

26] to represent a spectrum range of sustainable development dimensions spanning from weak to strong. Strong Sustainability allows natural capital depletion if it is replenished by manufactured assets (for example, using the funds from oil extraction to develop renewable energy). Weak Sustainability implies that resources can be swapped for inorganic wealth indefinitely. A variety of variables have contributed to the success of this cost-effective way of defining SD. Generally, this technique allows the concept to be thoroughly articulated quantitatively, attempting to overcome an often-noted impediment to its execution. This technique makes it easier to identify the conditions required for sustainable growth and to construct evaluation measures [

30].

According to Hopwood et al. [

31], the approach’s fundamental shortcoming is its focus on natural environmental challenges at the expense of socioeconomic outcomes. Furthermore, while this technique is applicable at the country level (and is used successfully at that level), its utility in analyzing SD efficacy at the sector level is doubted [

30].

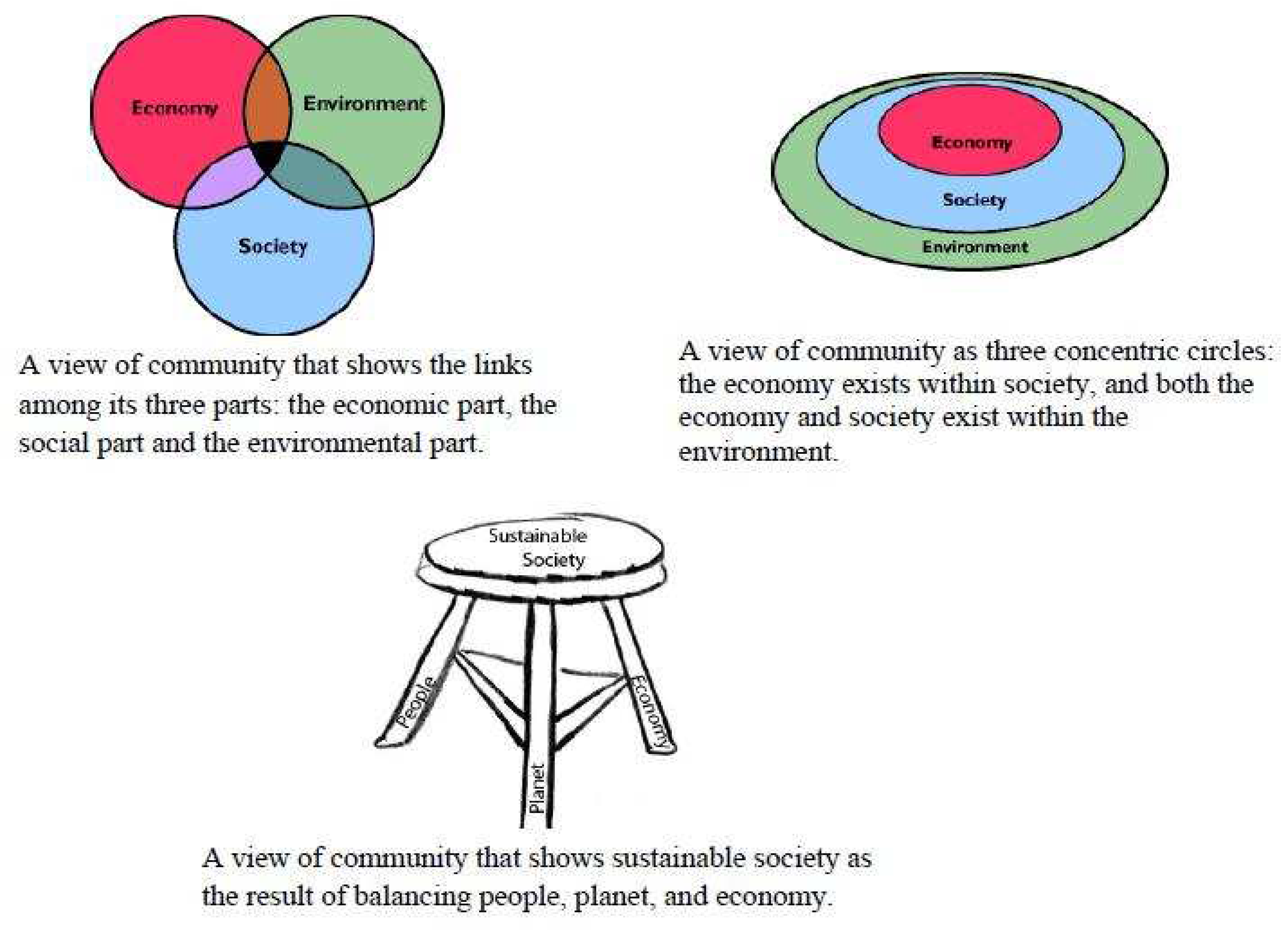

SD, according to Barbier, stands on “three legs” [

32]. This viewpoint, which expands on the WCED’s definition of SD, demonstrates a desire to balance sustainable development’s social, environmental, and financial elements. These three legs, generally drawn in a Venn diagram as three intersecting circles, are currently one of the most prevalent approaches for determining SD.

The three-legged model of SD has its skeptics criticized this SD example for four fundamental reasons. He claimed that such a technique might improve the current situation by allowing the state and other institutions to legitimize their SD-related goals. Furthermore, separating “social” and “economic” issues separates economic difficulties from a broader societal framework. He noted that considering SD could provide a misleading sense of harmony between the three elements, exposing flaws in the element relationships. According to Lehtonen [

33], the three-legged worldview does not instruct how to effectively examine the balance and collaboration between possibly conflicting economic, environmental, and social aims. His conclusive argument is predicated on the assertion that the three legs are not innately comparable.

Consequently, he acknowledged the contradictions in the sequence of the three components. To remedy these shortcomings, Lehtonen proposed utilizing the drawing in

Figure 1 to illustrate the three legs. This model for depicting sustainable development recognizes that acts related to humanity’s social context should be carried out within environmental limitations, and economic tasks should be carried out for the benefit of society [

33].

Figure 1.

The 3-legged Method to SD [

33].

Figure 1.

The 3-legged Method to SD [

33].

There have been several attempts to categorize the numerous SD explanations [

31]. Mebratu [

34] delineated the meanings of SD and classified them into three broad categories based on their origin, functionality, and conceptualization. He proposed a hypothetical assessment of these different definitions.

Cerin [

35] and Abubakar [

36] point out that SD is a crucial term in international development policies and programs, recognizing the ubiquity of WCED’s definition. It gives society a way to engage with the environment without jeopardizing the sustainability of the resources. Consequently, it is both a development paradigm and an ethos that inspires growing living standards without jeopardizing the earth’s natural ecosystems or causing ecological issues such as habitat destruction and water and air pollution that can contribute to species extinction and climate change [

37].

SD is a development model that utilizes resources to ensure their viability for future generations [

37]. Evers [

20] associates the notion with the organizing principle for accomplishing human development goals while conserving natural systems’ potential to continue supplying critical natural resources and ecosystem services to the economy and society. From this vantage point, SD seeks to accomplish social progress, environmental balance, and economic expansion [

17,

39]. Ukaga et al. [

1] emphasized the necessity to renounce harmful socioeconomic activities in favor of those having favorable effects on the environment, economy, and society in examining SD’s criteria.

It is argued that the necessity of sustainable development (SD) grows with each passing day because, despite the expanding population, the natural resources available to satisfy human wants and desires are not. As a result of this occurrence, there has always been a call for careful resource management to ensure that the needs of the present generation are always addressed without jeopardizing future generations’ ability to do the same, according to Hák et al. [

15]. SD aims to create a balance between social welfare, environmental protection, and economic progress. This supports the claim that SD includes trans-generational justice, which recognizes the immediate and long-term implications of Sustainability and SD [

13,

41]. According to Kolk [

42], this is feasible by merging economic, environmental, and social aspects into decision-making. Sustainability and social development are sometimes confused as synonyms and parallels, but they can be separated. According to Diesendorf [

43], sustainability is the goal or end result of the sustainable development process. Gray [

44] argues that whereas sustainability refers to a condition, SD relates to obtaining this condition.

3. Evolution of the Concept of Sustainable Development

Multiple studies have identified SD as a game changer and a significant global challenge [

45]. As a result, long-term development has been a top priority for nations worldwide [

46]. Despite this expanded scope of the evaluation, there are still gaps between SD and the goal it aims to attain. To comprehend this idea entirely, it is necessary to be familiar with the beginnings and significant development of SD [

47]. SD is misinterpreted when the concept’s dynamism is not recognized [

22]. There has been much discussion about the genesis and evolution of SD to acquire a more precise grasp of the concept.

Even though SD has grown in popularity and importance, in theory, its origins and history are typically disregarded or minimized. Even if some individuals feel evolution is meaningless, it may still be used to forecast future paths and defects, which is essential today and in the future [

48]. According to Pigou [

49], the concept of SD arose from economic research. According to the Malthusian population theory, the idea of the earth’s restricted land and resources supporting an ever-increasing population surfaced in the early 1800s [

50,

51]. Malthus prophesied in 1789 that human population growth would follow an astronomical pattern.

Because sustenance could only rise in arithmetic progression, population expansion was projected to surpass natural resource capacity to fulfill the needs of the rising population [

52]. As a result, if no steps were made to slow the population growth rate, natural resources would run out or be depleted, making people’s lives unpleasant [

53]. Because of the school of thought that innovation could be produced to prevent such an occurrence, the significance of this thesis was frequently overlooked. Challenges concerning the non-renewability of certain environmental assets occur worldwide, posing a threat to productivity and future economic growth due to environmental degradation and pollution [

54]. This raised questions about the viability of the intended development route and re-awakened awareness of the danger of Malthus’ prediction coming true [

55].

The highly regarded Brundtland Commission document was frequently cited in discussions of sustainable development. Although the team’s action plan catapulted SD to global prominence, the notion’s roots date back several decades. According to a group of specialists, inconsistencies involve advancement, and the role and relevance of biodiversity are essential to the argument’s evolution [

26].

Mebratu [

34] outlined a systematic view of human evolution and how much it affects the relationship between humans and their environment. The author emphasized the evolution of humanity’s fundamental values throughout history, which diminished ecology’s early significance. Industrialization, which began primarily in Europe, brought about dramatic changes in population distribution and social organization. This realization led to significant pressure on the planet regarding a steady supply of natural resources and the capacity of the environment to absorb waste (natural sinks) [

34]. Malthus and his contemporaries emphasized several issues in his 1798 work on the aspects of population increment and the sufficiency of food supply [

34]. Bell and Morse [

56] despised the hazards and abuse of innovations and materials that harm the environment.

The disparity between these concerns, such as environmental devastation, population growth, and technological development, is that until recently, these changes have all occurred reasonably, making them generally undetectable during an extensive period [

57]. In addition, the casual pace of change suggested there was enough time for the issues to vanish or be [

58]. In contrast, this is not the case over the past decade. As the magnitude of the abovementioned transformations surpasses the world’s maximum response rate, SD’s popularity grows. It is widely known that development policies are the fundamental culprits of the ongoing degradation of the planet and the escalation of global poverty. According to Elliot [

22], it is highly questionable whether the current societal and economic growth provisions can provide answers to present and future challenges. Mainly, sustainable development goes beyond a conventional ecological campaign and considers societal and financial concerns.

Moreover, several researchers view SD as an instruction of the planet and escalating global poverty. According to Elliot [

22], it is highly questionable whether the current societal and economic growth provisions can provide answers to present and future challenges. In this example, sustainable development extends beyond a traditional environmental initiative to include socioeconomic considerations. In addition, most researchers view SD as an alternative strategy to meet society's needs [

22].

Using the information on human population expansion, industrial expansion activities, and contamination, Meadows investigated in 1972 the limits to growth and whether the direction of global economic increment was sustainable [

52,

59]. Since the world is physically limited, Meadows concluded that the exponential growth of these three fundamental variables would eventually reach its limit [

60]. Nevertheless, according to several academics, researchers, and practitioners in the development field [

54,

61], the first significant worldwide recognition of the concept of sustainable development occurred in 1972 at the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm. According to Daly [

62] and Basiago [

63], previously treated as separate issues, development, and the environment can now be managed in a mutually rewarding manner.

The 1972 Stockholm Conference was the first to emphasize the difference in economic progress and ecological demands between industrialized and developing nations. According to Langhelle [

27], developing countries have been vocal about their unwillingness to recognize development restrictions that industrialized economies or governments have ignored. The conference was a massive success since it was the first time environmental problems were adequately conveyed to the rest of the globe [

21].

The notion of a sustainable society was conceived during the World Council of Churches-hosted meeting on Science and Technology for Human Development in 1974 [

26]. With a need for fair resource distribution, their principal emphasis was on social problems rather than environmental ones. Nonetheless, the Council recognized the need for sustainable development by recognizing the need to operate within the world’s finite resources [

26]. Many of the characteristics were approved and utilized to create the idea of sustainable development by the World Conference on Environment and Development (WCED).

The WCED was founded in 1984 with twenty-two (22) participants from developing and industrialized countries. The Commission was entrusted with creating a worldwide transformation strategy that included plans and suggestions for attaining SD, among other things [

25]. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) recommended a “new method of development” to support future human progress in “Our Common Future,” which has become the most generally recognized definition of sustainable development to date.

In the late 1990s, according to Elliot [

22], SD achieved widespread international recognition. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) increased SD’s popularity. The conference’s primary purpose was to identify the most critical activities to be carried out in the future concerning sustainable development. The recognition of the need for an international agreement to attain this resulted in the first-ever gathering of world leaders to deliberate on environmental issues [

22]. Consequently, a hundred and seventy-eight world leaders, including more than one hundred leaders and several nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), were in attendance. The meeting was also the first time that the need for long-term SD implementation guidelines for nations was discussed. The renowned “Agenda 21” [

22] was initiated at the meeting, where all governments were urged to develop nationalized SD guidelines.

In 1997, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) inspired the creation of the Kyoto Protocol, a legally binding agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). The presence of distinct but equal duties is fundamental to the convention. As a result, industrialized countries have received a lot of credit for recognizing that they are principally responsible for the high GHGs produced by more than 150 years of economic activity [

64]. Members of the Convention agreed to make efforts to reduce the economic, social, and environmental costs that environmental change and international commerce impose on their neighbors. The convention’s clear commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions is noteworthy.

South Africa hosted the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. The conference resulted in a political declaration, an action plan, and the institutionalization of several initiatives centered on the significant themes of water and sanitation, sustainable consumption and production, and energy [

65]. Following this, a succession of global summits, conventions, and plans were established. Rio+20, held in June 2012 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Earth Summit, was the most recent event. According to Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, the assembly emphasized the essential commitments associated with the Sustainable Development Goals (SD) [

66]. The summit’s final report, titled “The Future We Want,” advocated for a wide range of actions, including developing a system to identify SD objectives, hosting another SD discussion, and acknowledging the need for continual commitments to SD [

46].

Since the future of human civilization is in doubt, SD has been at the forefront of discussions on all continents. Because of this, all nations have been pressured to work together on a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the wake of the UN’s sustainable development summit (Rio + 20) in June 2012, all UN member nations dove headfirst into developing the SDGs. These goals were presented during a UN summit in New York in September 2015. To do this, the Sustainable Development Goals set forth a roadmap for development policy and finance over the next fifteen years. Seventeen goals comprise the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which seek to solve the world’s biggest environmental problems by 2030. The details of the SDGs are discussed in the subsequent sections.

Varied Perceptions and Criticisms of Sustainable Development

Scholarly writings showed several authors’ perspectives on SD. As described by Beckerman [

67], defenders of SD have portrayed it as a brilliant notion, a vital concept, and a purpose for global institutions to incorporate development and ecological problems effectively. On the other hand, critics see SD as nothing more than a hollow concept, lacking in solid content and including imposed philosophical views that are, at best, grandiose and overprotective [

68].

Mitcham [

69] identified a level of investigated or inventive ambiguity in the concept. This ambiguity concerning SD is a benefit rather than a disadvantage of the idea [

70]. He referred to it as ‘constructive ambiguity,’ arguing that it provides a chance to deepen comprehension of the word SD. O’Riordan [

71] expressed a similar viewpoint, admitting that the concept’s vagueness has contributed to the debate over its meaning [

22]. However, according to Parris and Kates [

72], the concept’s ambiguity lends an intriguing expression-like aspect, resolving what are seen to be factual disputes between the different components and varied temporary degrees of SD. This allows folks to pass off anything as SD, perhaps reducing the word to meaninglessness. This is especially evident in many SD definitions advocated by different organizations, which duplicate their own.

The link between SD and economic progress is uncertain in research publications. According to Shelbourn et al. [

73], sustainable development is primarily related to improving technology and economic progress while safeguarding the environment and natural resources. At first look, the notion of sustainable development seems to be concerned with the two incompatible aims of economic expansion and the prudent use of the earth’s natural resources [

74]. For example, the WCED statement proposes a five to ten-fold rise in economic growth while considering the world’s environmental restrictions. The uncertainty surrounding SD in this respect, according to Mitcham [

69], is vital for bridging any gap between “anti-development preservationists” and “pro-development developmentalists.”

According to Dresner [

26], SD has traditionally been used to refer to outmoded economic development, while environmental considerations have always been overlooked. Daly [

62] used a substantial difference in definition between the terms’ growth’ and ‘development’ to separate SD from sustainable growth. Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “grow” as gradually expanding in size by adding inorganic material. The same vocabulary defines ‘develop’ as generating or producing anything, particularly by purposeful effort over time [

75]. Daly [

62] proposed that growth refers to quantitative physical expansion, while development relates to qualitative advancement, particularly in potential. In terms of SD, he emphasizes qualitative rather than quantitative improvements.

According to Pezzey [

24], who defines “economic development” as the rising total use of produce, “development” is assessed in terms of monetary value rather than physical units. According to Pezzey [

24], economic yield growth should not relate to physical throughput increase. He admits, however, that ‘development’ still has shortcomings, such as ignoring environmental quality and other social factors and revenue distribution which development fixes.

Earlier talks indicate that SD is more concerned with the interaction between the ecological, equitable, and economic components of development rather than conserving the environment or controlling economic growth [

76]. Donella Meadows, a well-known academic expert on the subject, believes that the etymological disjunctions around SD are adequate, given the intricacy of all social developments [

26]. She contended that the situation should not remain stagnant despite differing and contradicting views about SD. Organizational objectives and political orientations versus unambiguous and unbiased scientific viewpoints [

34].

Furthermore, according to Dresner [

26], as mentioned earlier, the ambiguity or incoherence surrounding SD does not constitute a useless notion. As a result of SD’s obscurity, Jacobs [

77] refers to it as a controversial notion rather than a meaningless one. This implies that the SD translation is subject to several interpretations. As a result, Jacobs’ [

77] perspective on SD is analogous to notions like freedom or equality, whose fundamental meanings are broadly acknowledged despite persistent doubts about how they should be understood and applied. According to Mitcham [

69], SD is ideal, analogous to love or nationalism, something necessary and even noble that may become a term and be used by ideologues. Redclift has a similar stance, noting that, identical to fatherhood, it is unpleasant not to support SD [

22]. Regardless, the premise is plagued with flaws. Some even see it as an emerging meta-discipline proposing an entirely new area of study [

78].

The accompanying discussion shows no consistent definition of SD in the scientific literature. Despite the SD concept’s enormous popularity and extensive attention, most authors and academics agree that there is considerable uncertainty regarding its definition, aims, and implementation. One could claim that the absence of a continuous meaning constitutes a critical political potential since an exact meaning can exclude those whose perspectives are not considered in such a meaning [

70]. SD’s ideological, philosophical, and methodological importance is expanding. According to Robinson [

70], it is doubtful that a complete, understandable technique for dealing with SD will develop very soon. However, SD standards will continue to be adopted in multiple dimensions until this theoretical breakthrough happens.

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL)

The TBL is an SD model with three application aspects: society, environment, and economy. This is distinct from typical development techniques in that it considers both nature and society. TBL levels are also known as people, earth, and profits. Preservationists struggled with SD measures and models before Elkington articulated the SD concept as the “3Ps.” Over the past three decades, the number of scholarly papers on SD has grown. Individuals who have researched and implemented SD within and outside the academic community would broadly agree with Andrew Savitt and Jenning's [

79] definition of TBL. TBL captures the essence of SD by assessing the global impact of an organization’s activities, including the benefit and investor values, as well as social, human, and ecological capital.”

SD emphasizes a positive transformation trajectory focused on social, economic, and environmental issues as a forward-thinking and visionary development paradigm. Taylor [

80] sees sustainable development’s three most critical components as social equality, environmental protection, and economic growth. This implies that three conceptual pillars principally support the SD notion. These pillars of sustainability include economic, social, and ecological.

Economic Sustainability

Economic Sustainability involves a manufacturing system that meets current demand without jeopardizing future needs [

81]. Because it was assumed that natural resource supply was infinite, economic theory has traditionally overemphasized the market’s ability to allocate resources properly [

82]. They also believed that technological advancement and economic growth would go hand in hand, with technology ultimately replacing natural resources used in production [

83]. Natural resources are recognized today as finite, and not all can be restored or regenerated. The expansion of the economic system has put pressure on the availability of natural resources, necessitating a reconsideration of fundamental economic ideas [

59,

63,

82]. Consequently, many academics have questioned the possibility of uncontrolled consumption and progress.

Markets are the places in an economy where transactions take place. According to Dernbach [

61], decision-makers use guiding frameworks to analyze transactions and make economic activity judgments. The three basic economic activities are production, distribution, and consumption, but the accounting system used to control and assess the economy in connection to these activities considerably distorts values, which is bad news for society and the environment [

84]. According to Allen and Clouth [

85], the earth’s finite natural resources are utilized to sustain and protect human existence. Dernbach [

61] argued that although population expansion increases human requirements for food, clothes, and housing, the world’s means and resources cannot be grown endlessly to fulfill these needs.

Furthermore, Retchless and Brewer [

86] contend that while economic expansion seems to be the primary emphasis, key cost concerns such as the effect of pollution and depletion are overlooked. At the same time, increased demand for products and services drives markets and compromises environmental damage [

87]. To achieve economic sustainability, choices must be made in the fairest and financially responsible way possible while also considering other sustainability aspects [

88].

Social Sustainability

Social Sustainability includes justice, autonomy, access, inclusiveness, cultural image, and institutional consistency [

62]. People are essential because progress is about people (Benaim & Raftis, 2008). Littig and Grießler [

90] define social sustainability as a framework that eliminates poverty. However, in a broader sense, “social sustainability” refers to the interaction between social issues such as impoverishment and environmental harm [

91]. According to the social sustainability concept, eliminating poverty should not result in unwarranted environmental deterioration or unstable economic situations. Society should endeavor to decrease poverty within the restrictions of its present economic and natural resource base [

92].

According to Saith [

93], social sustainability must promote the evolution of people, communities, and civilizations while encouraging gender equality in education, healthcare, and other professions, as well as global peace and stability. According to Benaim and Raftis [

89], achieving social sustainability is challenging since it seems to be a complicated and overpowering societal component. In contrast to the natural and economic systems, where flows and cycles can be seen, the social system dynamics are exceedingly intangible and challenging to describe [

89,

94]. According to Everest-Phillips [

95], success in the social system occurs when “people are not exposed to situations that limit their potential to satisfy their needs.”

According to Kolk [

42], social sustainability does not include fulfilling everyone’s desires. Instead, it attempts to create conditions that enable everyone to meet their own needs if they want. Individuals, organizations, and communities must work together to remove any barriers to social sustainability to advance [

96]. From a systems perspective, understanding the nature of social dynamics and how these structures develop is crucial for social Sustainability [

97]. According to Gray [

44] and Guo [

98], social sustainability encompasses various issues such as human rights, gender equity and equality, public participation, and the rule of law, all of which promote peace and social stability in the long run.

Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustenance or sustainability refers to the natural environment’s resilience and production to support human existence. The link between ecosystem health, natural carrying capacity, and ecological Sustainability [

99]. It necessitates the long-term utilization of natural capital as both a waste sink and a source of economic inputs. The premise is that trash cannot be created faster than the environment can absorb it and that natural resources cannot be exhausted quicker than they can be restored [

20]. This is done to preserve balance within the constraints or limits of the earth’s systems.

However, since technological advancement may not support exponential expansion, the pursuit of unfettered growth places ever-increasing demands on the universe’s system and puts these constraints under strain. The evidence for eco-efficiency problems is growing [

100]. Climate change, for example, demonstrates the need for environmental sustainability. Climate change refers to long-term changes in the climatic system caused by natural climate variability or human intervention. The changes include warming the climate and seas, melting ice sheets, rising sea levels, rising ocean acidity, and increasing greenhouse gas concentrations [

82].

The changes in weather conditions have affected biodiversity. Higher temperatures, for example, have been shown to alter population numbers commonly, animal and plant species distributions, and animal and plant migratory patterns, according to Kumar et al. [

101]. While there are various apocalyptic forecasts, the full implications of global warming remain unknown, according to Ukaga et al. [

1]. According to Campagnolo et al. [

102], all civilizations must adapt to the new realities surrounding ecological management and physical constraints to development to assure sustainability.

The current pace of biodiversity loss surpasses the natural rate of extinction. Climate change is expected to cause species to migrate to higher latitudes and altitudes and affect the global plant cover. A species’s chances of survival are reduced if it cannot adapt to new geographic ranges. According to predictions, sea level rise might destroy around 20% of coastal wetlands by 2080. These are significant environmental sustainability challenges because they impact the environment’s capacity to stay resilient and productively stable to sustain human existence and progress.

Principles of Sustainable Development

SD necessitates the use of certain guiding concepts. However, when it comes to the basics of sustainable development, the economy, environment, and society are often prioritized [

4,

103]. They are particularly relevant to manufacturing systems, family planning, human capital management, contemporary cultural preservation, and public engagement. They also involve ecological and biodiversity conservation [

104].

Ecosystem preservation is a fundamental component of sustainable development. All living things will die unless the environment and biodiversity are preserved. The earth’s finite resources and methods are inadequate to fulfill everyone’s requirements. Resource consumption must not exceed the earth’s carrying capacity for sustainable development since the over-exploitation of resources has detrimental impacts on the environment [

105]. This implies that development efforts must be aligned with the earth’s potential. As a result, it is critical to have alternate energy sources, such as solar, rather than depending too much on hydroelectricity and petroleum-based goods [

104].

Furthermore, population management is essential to accomplish SD [

80]. People live by using the planet’s finite resources. Population expansion raises human requirements for food, clothes, and shelter, yet there are limitations to how much the world’s resources can be increased. As a result, SD requires population management and control.

According to Wang [

106], another critical SD tenet is effective human resource management. Individuals are responsible for ensuring that the values are followed. Individuals are accountable for environmental protection and use. Individuals’ activities determine whether there is peace. As a consequence, the value of human resources in the pursuit of SD is increasing. It means that people’s knowledge and abilities must be expanded to take better care of the environment, the economy, and communities [

107]. Because a sound mind dwells in a healthy body, this may be mainly accomplished via education and training and the provision of appropriate healthcare services. These variables may also aid in developing a favorable attitude toward nature. Education may also convince society to prioritize human values, environmental preservation, and ethical manufacturing practices.

Furthermore, it is claimed that involvement in the SD process is critical to its success and long-term viability [

98]. The foundation of the argument, which employs systems theory, is that SD cannot be accomplished via the efforts of a single person or organization. All relevant persons and organizations must share this obligation. SD is founded on participation, which necessitates that people adopt positive attitudes to achieve meaningful progress with responsibility and accountability for long-term sustenance.

Tjarve and Zemte [

12] argue that SD thrives through encouraging progressive social traditions, practices, and political culture. Advanced traditional and political culture must be established, fostered, and spread to keep society together and contribute to preserving and enjoying the environment for SD. In a nutshell, the fundamental premise of sustainable development is the systematic incorporation of environmental, social, and economic considerations into all decision-making across generations.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The SDGs provide a balanced agenda of economic, social, and environmental goals and objectives. To achieve the SDGs, governments must recognize the possibility of trade-offs, acknowledge their existence, and devise solutions to address them. They should also look for synergies to help them accomplish their real-world objectives.

Furthermore, it is said that involvement in the SD process is critical to its effectiveness and Sustainability [

98]. The argument’s assumption, which draws on systems theory, is that a single person or organization cannot accomplish SD. All relevant persons and organizations must share this commitment. SD is founded on the principle of participation, which requires positive attitudes to achieve genuine growth with responsibility and accountability for long-term sustainability.

According to Tjarve and Zemte [

12], SD flourishes through advocating for progressive social traditions, practices, and political culture. An advanced political and traditional culture is required, fostered, maintained, and promoted in SD to sustain social cohesiveness and contribute to preserving and enjoying the environment. Integrating environmental, social, and economic issues into all areas of intergenerational choice is the core concept of sustainable development. The SDGs provide a well-balanced mix of economic, social, and environmental aims and objectives. To accomplish the SDGs, countries must understand the potential of trade-offs, admit their presence, and devise methods to resolve them. They should also seek synergies that might help them achieve real-world goals.

Although not legally binding, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a normative framework for development. Governments and other interested parties must develop a national and regional implementation plan. The 2030 Agenda is neither a roadmap for implementing specific actions nor a strategy for coping with the inevitable challenges and trade-offs during implementation.

The Sustainable Development Goals seek to improve human dignity and prosperity while protecting the vital biophysical processes and ecological services that keep life on earth alive. They recognize that providing basic social needs like education, health, social protection, and job opportunities must coexist with methods that promote long-term economic development, peace, and justice. Furthermore, they recognize the need to tackle climate change and improve environmental preservation.

Although governments have emphasized the SDGs’ integrated, indivisible, and corresponding character [

108], substantial linkages and interdependencies are seldom apparent in descriptions of the goals and accompanying targets. In 2015, the International Council for Science (ICSU) discovered strong connections between SDGs goals and targets. To support a more strategic and integrated execution, it is now critical to analyze the main links that exist within and between these goals and their respective targets. This article describes a methodology for characterizing the spectrum of positive and negative interactions across various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and evaluates it by applying it to an initial set of four SDGs: SDG2, SDG3, SDG7, and SDG14. This list of critical SDGs for human well-being, ecological services, and natural resources is not prioritized.

Despite the scientific community’s emphasis on the importance of a systems approach to sustainable development, policymakers are now faced with the challenge of implementing the SDGs concurrently to achieve progress in the economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Agenda 2030 splits the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into five critical themes known as the five Ps: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnerships [

6,

39,

98]. They aim to address the underlying causes of poverty by addressing issues such as hunger, health, education, gender equality, water and sanitation, energy, economic growth, industry, innovation & infrastructure, inequalities, sustainable cities & communities, consumption & production, climate change, natural resources, peace & justice. According to the SDGs, sustainable development seeks social progress, environmental balance, and economic growth.

4. Discussion

The systemic review revealed some underlying themes and patterns in the various aspects of the SD discourse. The meaning and how stakeholders understand SD and its principles are inconsistent and continue to evolve. Especially in applying the SD concept and its principles in other practical fields. Kates et al. [

21], however, are of the view that the definition and application of the SD concept and principles must be consistent and without any form of bias. This situation results from the background or perspectives from which various stakeholders view and understand the idea. Dresner [

26] and other researchers refer to this as ‘bias analysis’ of the concept.

Though the principle of SD keeps evolving, and new ones are being introduced, the majority of these principles are still classified under the three pillars (environmental, social, economic) of SD. Ji [

103] and Mensah and EnuKwesi [

4] opined that most proponents of the SD concept tend to place a considerable emphasis on the economy, environment, and society when it comes to the principle and fundamentals of the SD concept.

Although the concept of SD was indirectly proposed more than a century ago, it wasn’t until roughly 50 years ago that it was formally introduced and approved. The UN has convened numerous conferences to explore the SD idea and develop various working documents and policies to support and spread the concept across all UN member states. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals by all member nations is the current strategy the UN uses to promote the SD concept and persuade all countries to use it in all areas of their development. Though the SDGs have received relatively minor criticism, most experts agree that they represent one of the most effective efforts to advance the SD notion. According to Fukuda-Parr [

109], the SDGs integrate a more significant and transformative agenda that better reflects the complex issues of the 21st century and the need for structural reforms in the global economy. They also address several of the MDGs’ significant flaws.

One of the most important findings of this study is that, up until 2010, the SD concept was heavily criticized for focusing too much attention on the environmental pillar at the expense of society and the economy. This gave rise to the notion of striking a balance or making a trade-off in applying the SD concept. After 2010, the focus appears to have shifted from the environment to society, with the three pillars being balanced. The emphasis on societal issues concerning the SDGs supports this. Gupta and Vegelin [

110] reviewed the SDGs and concluded that while the text does quite well in terms of social inclusivity, it does less in terms of ecological and relational inclusivity. They also implied that there was a risk that implementation processes would also focus more on social inclusivity than on environmental and relational inclusivity.

As stated above, the main initiative that is championing the implementation of the SD concept is the SDGs implementation. Globally, all UN member countries have agreed to implement the various SDGs in the development agenda. The SDGs are distinguished because their development goals and objectives are essentially autonomous but interrelated [

111]. According to the SDGs, trade-offs or conflicts, as well as interrelations or efficiencies, have global and national implications. Complementarities imply that accomplishing one aim might help others achieve theirs. Addressing climate change problems, for example, may benefit the security of energy sources, human health, biodiversity, and oceans [

112]. According to Fasoli [

113], it is critical to recognize that the SDGs are not stand-alone goals. They are linked, indicating that completing one lead to gaining another, and as such, they should be viewed as critical pieces of a large and complicated jigsaw puzzle [

101]. Taylor [

80] proposes that different countries investigate the various goals to determine which ones are more likely to be catalytic and have multidimensional effects while also aiming to fulfill the complete agenda. This is done to capitalize on the complementarities of the SDGs. According to Meurs and Quid [

114], this decision must consider each nation’s resources and ambitions. It’s also worth noting that because many of the target regions and objectives overlap, a single indicator may be used to measure progress toward some of them.

Aside from duplication and synergy, the SDGs face conflicts and trade-offs that need difficult decisions that may result in temporary winners and losers. For example, Espey [

115] says that removing trees to boost agricultural productivity for food security may jeopardize biodiversity, while Mensah and Enu-Kwesi [

4] believe that food security may be undermined if food crops are transferred to biofuel production for energy security. Consequently, achieving a balance between rapid economic progress that reduces poverty and environmental preservation is challenging.

Furthermore, it is claimed that the SDGs are tied to competing stakeholder interests. According to Le Blanc [

112], climate change mitigation (Goal 13) is a prime example of competing interests. In other words, individuals who may be harmed in the short term, such as fossil fuel businesses and their employees, may perceive themselves as “losers” if forced to adapt, even though society as a whole will ultimately “win” by avoiding the dangers and impacts of climate change [

111]. According to Keitsch [

116], trade-offs may offer governance issues in complex SDG contexts where the interests of several stakeholders conflict. Another significant challenge, according to Spahn (2018), is ensuring responsibility and accountability for the SDGs’ progress. Several critics, researchers, and academics [

80,

117,

118] argue that this needs the creation of proper metrics and procedures for tracking and analyzing SDG accomplishment, particularly at the national level [

105]). In this regard, it would be crucial to assess inputs and outputs to see whether nations are meeting their aims and monitoring outcomes to discover if they are spending what they promised to address the problems [

119,

120].

Fair work opportunities, energy, sustainable cities, food security and sustainable agriculture, water, oceans, and disaster preparedness are among the concerns that require immediate action. According to DESA-UN [

121], an additional 220 million hectares of land would be needed by 2030 to feed the world’s growing population. This is about food and farming. Attaining the SDGs in food and agriculture is expected to bring in

$2.3 trillion in savings and revenue. Reducing food waste, reforestation, and developing low-income food markets are the top three food system opportunities, and they are expected to generate 71 million jobs in the food sector, including 21 million jobs in Africa and 22 million jobs in India, where there is ample cropland and low productivity, creating favorable growth conditions [

121].

According to Ritchie and Roser [

122], two-thirds of the world’s population will reside in cities by 2050, up from 50% today This will have a number of socioeconomic costs and benefits Businesses may benefit from promoting livable and healthy communities by expanding operations and creating more jobs According to Jaeger, Banaji, and Calnek-Sugin [

123], achieving the SDGs in cities has a potential profit of

$3.7 trillion and would create around 166 million new jobs in construction, transportation, and other urban opportunity sectors Because of the potential benefits of circular business models, renewable energy, energy efficiency, and energy access, over 1.5 billion more energy consumers are predicted by 2030, producing an additional 86 million jobs and

$4.3 trillion in income Furthermore, according to Jaeger, Banaji, and Calnek-Sugin [

123], better healthcare that takes advantage of technological advancements and other advancements in the global health system could generate

$1.8 trillion in revenue, resulting in the creation of 46 million jobs through new business opportunities in the health sector.

Furthermore, environmentally responsible infrastructure is necessary to boost productivity and economic production [

124]. According to Kappelle et al. [

125], developing-country infrastructure investment must grow from

$0.9 trillion to

$2.3 trillion annually by 2020. This includes the

$200-

$300 billion in US dollars needed to guarantee that infrastructure emits fewer greenhouse pollutants and is more adaptable to climate change. According to the United Nations Environment Programme [

126],

$340 billion is a relatively modest estimate of the yearly expenses involved with preventing and adapting to climate change through 2030. It tackles just one hazard to the global environmental commons: global warming. Official development aid (ODA), at over

$130 billion per year, is a relatively minor source of support [

126]. Overexploitation risks and the massive quantities of money necessary for the various projects are two additional costs linked with SDG implementation. These highlight some socioeconomic expenses and advantages of sustainable development, although measures for assessing the SDGs’ effectiveness are still being debated [

102].

Given the debate about the costs and benefits of the SDGs, trade-offs, complementarities, and complexity, the main question is how the UN can compel governments to adopt them. It is advocated that the UN respect national policies and objectives while considering various national realities, capacities, and levels of development and ensuring that they are centered on sustainable development [

111]. Even though the SDGs fundamentally apply to poor and developed countries, the difficulties they confront may vary based on each country’s unique circumstances [

127]. To achieve its goals, the UN should emphasize universality while maintaining a country-specific perspective [

119]. The United Nations may exert pressure on wealthier nations like the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada to reform their own cultures and economies sustainably while assisting impoverished countries in accomplishing SD. The United States should help nations by encouraging initiatives that foster active involvement, engagement, conversation, and general national capacity building. While promoting good governance, the United States may aid all nations with inclusive education, legislation, and resource distribution [

107]. Because there is evidence that utilizing suitable technology, for example, might minimize trade-offs between environmental and economic repercussions, the UN may encourage innovation and appropriate technology. According to Breuer et al. [

120], the UN should engage not just governments but also other major players, such as industry, NGOs, and civil society, and create feedback loops to guarantee that the SDGs are genuinely executed.

5. Conclusions

Several governmental and nongovernmental organizations and all relevant stakeholders have endorsed it as a viable development model. This is because the majority, if not all, proponents and advocates of the paradigm seem to agree that adhering to the tenets and principles of SD can aid in addressing the problems that humanity is currently facing, such as climate change, ozone layer depletion, water scarcity, vegetation loss, inequality, insecurity, hunger, deprivation, and poverty.

SD’s ultimate objective is to establish a balance of environmental, economic, and social sustainability, and these pillars serve as the cornerstone for this purpose. Without taking a position, one may argue that the availability of adequate health systems, peace and respect for human rights, decent employment, gender equality, high educational standards, and the rule of law are all necessary for a society’s sustainability. Good physical design, land usage, and the preservation of ecology or biodiversity promote environmental sustainability. However, economic sustainability depends on adequate production, distribution, and consumption. Although the literature contains numerous definitions and interpretations of sustainable development (SD), intergenerational equity is implicit in the dominant perspectives on the concept. It recognizes both the short- and long-term implications of sustainability to meet the needs of both current and future generations.

To achieve SD, social, environmental, and economic factors must be considered through coordinated efforts at multiple levels. For the SDGs to be successfully implemented, intricate relationships between the goals and their targets must be untangled. The fundamental pillars of an integrated approach to sustainability must be implemented simultaneously, and the tensions, trade-offs, and synergies between them must be managed. International organizations and institutions such as the United Nations, national governments, nongovernmental organizations, and civil society organizations must play a pivotal role in resolving the contradictions between sustainability and sustainable development.

People’s commitment makes sustainable development work; therefore, greater public participation is required to put the concept into effect. Everyone must understand that ethical consumption, production, the environment, and progressive social goals are critical to their survival as well as the survival of future generations. Only by integrating the pillars, producing positive synergies, and removing negative synergies can significant SD be made. It implies that “sustainability” is a dynamic economic, social, and environmental system. For “SD” to be effective, they must be followed simultaneously; as a result, every choice should strive to foster natural system balance and development. Although everyone is responsible for promoting sustainable development, governments, civil society organizations, and global, regional, and national organizations are urged and expected to take responsibility, lead, and participate in society.