Submitted:

03 February 2023

Posted:

10 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Workload of Nurses

1.2. Nursing Care for a Patient with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Purpose and Research Hypotheses

- 1.

- H0 The workload of a nurse in the care of a patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, determined on the basis of TISS–28, is higher than 46 points.

- 2.

- H0 The workload of a nurse in the care of a patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, determined on the basis of NEMS, is higher than 46 points.

- 3.

- H0 The workload of a nurse in the care of a patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, determined on the basis of NAS, is higher than 100 points.

- 4.

- H0 The ratio of nursing care for a patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia of 1:2 is sufficient.

- 5.

- H0 There is a correlation of results for TISS–28 & NEMS and TISS–28 & NAS.

- 6.

- H0 There is a correlation of results for NEMS and NAS.

3. Results

3.1. The Workload of a Nurse in the Care of a Patient with CDH in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit on the Basis of TISS–28

3.3. The Workload of a Nurse in the Care of a Patient with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia on the Basis of NEMS

3.4. The Workload of a Nurse in the Care of a Patient with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia on the Basis of NAS

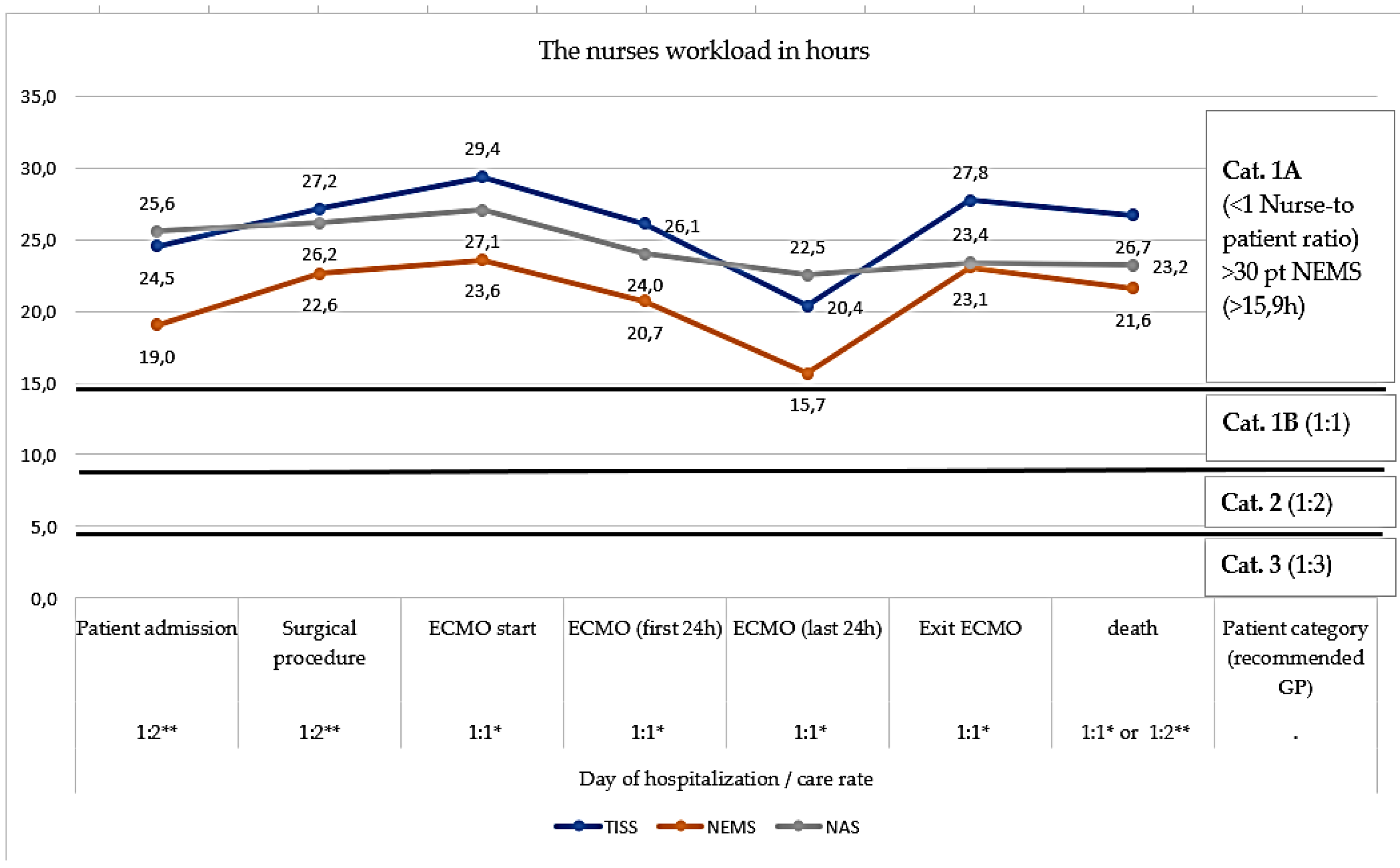

3.5. Demand for Nursing Care for a Patient with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia on the Basis of TISS–28, NEMS and NAS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- A nurse-to-patient ratio >1:1 is recommended over a patient with CDH from the first day of hospitalization.

- 2.

- A patient with CDH should receive the care they need, so it is recommended to use standardized tools of TISS–28, NEMS and NAS to measure the workload of nurses.

- 3.

- Use of TISS–28, NEMS and NAS tools can help to increase the level of patient safety in ICU.

- 4.

- Development of a model for the use of TISS–28, NEMS and NAS tools to measure the workload in neonatal intensive care units is the goal of further research.

- 5.

- It is necessary to implement a model for measuring the workload of nurses in neonatal intensive care units, taking into account the evaluation of work and its optimization.

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | By calculating 46 points per daily workload (46 points x 10.6 minutes x 3 / 60 = the result is the number of hours worked during 24 hours of work), a result of 24.38 h/24h hours during 24 hours of work of a nurse was obtained. |

References

- Amiri, A., & Solankallio-Vahteri, T. (2020). Analyzing economic feasibility for investing in nursing care: Evidence from panel data analysis in 35 OECD countries. 7(1), 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P., Recio-Saucedo, A., Dall’Ora, C., & Briggs, J. (2018). The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: A systematic review. 74(7), 1474–1487. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Wojcik, B., Gaworska-Krzemińska, A., J Owczarek, A., & Kilańska, D. (2020). In-hospital mortality as the side effect of missed care. 28(8), 2240–2246. [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P., & P. Gurses, A. (2008). Nursing Workload and Patient Safety—A Human Factors Engineering Perspective.

- Cisek, M., Przewoźniak, L., Kózka, M., & Tomasz Brzostek, T. (2013). Obciążenie pracą podczas ostatniego dyżuru w opiniach pielęgniarek pracujących w szpitalach objętych projektem RN4CAST (T. 11).

- Yatsue Conishi, R. M., & Gaidzinski, R. R. (2007). Nursing activities score (NAS) como instrumento para medir carga de trabalho de enfermagem em UTI adulto. Rev Esc Enferm. 41(3), 346–354. [CrossRef]

- Sprung, C. L., Artigas, A., Kesecioglu, J., & Pezzi, A. (2012). The Eldicus prospective, observational study of triage decision making in European intensive care units. Part II: intensive care benefit for the elderly. 40(1), 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Panunto, M. R., & Guirardello, E. de B. (2012). Carga de trabalho de enfermagem em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva de um hospital de ensino. 25(1), 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L. A., & Padilha, K. G. (b.d.). Fatores associados à carga de trabalho de enfermagem em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva. 41(4), 645–652. [CrossRef]

- Wiskow, C. (2006). Pomiar obciążenia pracą w określaniu potrzeb kadrowych. Przegląd piśmiennictwa. Opracowanie dla Międzynarodowej Rady Pielęgniarek. http://www.ptp.na1.pl/pliki/ICN/ICN_pomiar_obciazenia_praca_ 03_11_2009.pdf.

- Ball, J. E., Murrells, T., Rafferty, A. M., Morrow, E., & Griffiths, P. (2014). Care left undone’during nursing shifts: Associations with workload and perceived quality of care. 23(2), 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Guccione, A., Morena, A., Pezzi, A., & Iapichino, G. (2004). The assesment of nursing workload. 70(5), 411–416.

- Canabarro, S. T., Velozo, K. D. S., Eidt, O. R., Piva, J. P., & Garcia, P. C. R. (2010). Nine Equivalents of Nursing Manpower Use Score (NEMS): A study of its historical process. 31(3), 584–590. [CrossRef]

- Kelly Dayane Stochero Velozo, Pedro Celiny Ramos Garcia, Jefferson Pedro Piva, & Humberto Holmer Fiori,. (2017). Scores TISS–28 versus NEMS to size the nursing team in a pediatric intensive care unit. 15(4), 470–475. [CrossRef]

- Irimagawa, S., & Imamiya, S. (1993). Industrial hygienic study on nursing activities investigation on heart rate and energy expenditure of cranial nerves and ICU ward nurses. 65, 91–98.

- Debergh, D., Myny, D., Van Herzeele, I., Van Maele, G., & Reis Miranda, D. (2012). Measuring the nursing workload per shift in the ICU. 38(9), 1438–1444. [CrossRef]

- Campagner, A. O. M., Pedro Celiny Ramos Garcia, P. C. R., & Piva, J. P. (2014). Aplicação de escores para estimar carga de trabalho de enfermagem em unidade de terapia intensive pediátrica. 26(1), 36–43.

- Monroy, J. C., & Hurtado Pardos, B. (2002). Utilization of the nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS) in a pediatric intensive care unit. 13(3), 107–112.

- Moore, K. L., Persaud, T. V. N., & Torchia, M. G. (2021). Embriologia i wady wrodzone. Od zapłodnienia do urodzenia. Urban & Partner.

- Bohosiewicz, J. (2013). Diagnostyka i terapia wad płodu aktualny stan wiedzy i praktyki (5. wyd., T. 67). Ann. Ac. Silea.

- Program kompleksowej terapii wewnątrzmacicznej w profilaktyce następstw i powikłań wad wrodzonych i chorób dziecka nienarodzonego – jako element poprawy stanu zdrowia dzieci nienarodzonych i noworodków na lata 2018–2020. (2018). Program Polityki Zdrowotnej Ministra Zdrowia ‘. https://www.gov.pl/attachment/85de995a-ab00-4df0-9dea-f32400311e9d.

- Bösenberg, A. T., & Brown, R. A. (2008). Management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008. 21(3), 323–331.

- de Buys Roessingh, A. S., & Dinh-Xuan, A. T. (2009). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Current status and review of the literature. 168(4), 393–406. [CrossRef]

- Logan, J., Rice, H., Goldberg, R., & Cotten, C. (2007). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: A systematic review and summary of best-evidence practice strategies. 27(9), 535–549. [CrossRef]

- Deprest, J. A., Gratacos, E., Nicolaides, K., & Done, E. (2009). Changing perspectives on the perinatal management of isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe. 36(2), 329–347. [CrossRef]

- Lango, R., Szkulmowski, Z., Maciejewski, D., & Kusza, K. (2009). Protokół zastosowania pozaustrojowej oksygenacji krwi (ECMO) w leczeniu ostrej niewydolności oddechowej. 51(4).

- Mugford, M., Elbourne, D., & Field, D. (2008). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe respiratory failure in newborn infants. 16(3), CD001340.

- Bryner, B. S., West, B. T., Hirschl, R. B., & Drongowski, R. A. (2009). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Does timing of repair matter? 44(6), 1165–1171. [CrossRef]

- Ducci, A. J., Zanei, S. S. V., & Whitaker, I. Y. (2008). Nursing workload to verify nurse/patient ratio in a cardiology ICU. 42(4), 673–680.

- Velozo, K. D. S., Costa, C. A. D., Tonial, C. T., Crestani, F., Andrades, G. R. H., & Garcia, P. C. R. (2021). Comparison of nursing workload in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit estimated by three instruments. 55. [CrossRef]

- Queijo, A., & Padilha, K. (2004). Instrumento de medida da carga de trabalho de enfermagem em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva: Nursing Activities Score (N.A.S). 23, 114–122.

- Castro MCN, Dell’Acqua MCQ, Corrente JE, Zornoff DCM, Arantes LF. (2009). Aplicativo informatizado com O nursing activities score: Instrumento para gerenciamento da assistência em unidade de terapia intensiva. Texto Contexto Enferm. 18(3), 577–585. [CrossRef]

- Katia Grillo Padilha, Regina M Cardoso Sousa, Miako Kimura, & Ana Maria Kazue Miyadahira. (2007). Padilha KG, Sousa RM, Kimura M, et al. Nursing workload in intensive care units: A study using the Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System–28 (TISS–28). [CrossRef]

- Cudak, E., & Dyk, D. (2007). Ocena nakładu pracy pielęgniarek na oddziale intensywnej terapii na podstawie skali Nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS). 15(1), 7–12.

- Lucchini, A., Elli, S., De Felippis, C., Greco, C., Mulas, A., Ricucci, P., Fumagalli, R., & Foti, G. (2019). The evaluation of nursing workload within an Italian ECMO Centre: A retrospective observational study. 55. [CrossRef]

- Rothen, H. U., Küng, V., Ryser, D. H., Zürcher, R., & Regli, B. (1999). Validation of “nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score’on an independent data sample. 25, 606–611. [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, I., & Gotlib, J. (2018). Czym jest racjonowanie opieki pielęgniarskiej? 7(2), 40–47.

- VanFosson, C. A., Jones, T. L., & Yoder, L. H. (2016). Unfinished Nursing Care: Am Important Performance Measure for Nursing Care. 64(2), 124–136. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M., Ausserhofer, D., Desmedt, M., Schwendimann, R., Lesaffre, E., Li, B., & De Geest, S. (2019). Schubert M, Ausserhofer D, Desmedt M, et al. Levels and correlates of implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals – a cross sectional study. 50, 230–239. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R., & Scott, P. A. (2018). Missed care: A need for careful ethical discussion. 25(5), 549–551. [CrossRef]

- Gibbon, B., & Crane, J. (2018). The impact of ‘missed care’on the professional socialisation of nursing students: A qualitative research study. 66, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-H., Kim, Y.-S., Yeon, K. N., You, S.-J., & Lee, I. D. (2015). Effects of increasing nurse staffing on missed nursing care. 62(2), 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Tubbs-Cooley, H. L., Mara, C. A., Carle, A. C., Mark, B. A., & Pickler, R. H. (2019). Association of Nurse Workload With Missed Nursing Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. 173(1), 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, B. J., & Xie, B. (2014). Errors of Omission: Missed Nursing Care. 36(7).

- Carvalho de Oliveira, A., Garcia, P. C., & Nogueira, L. de S. (2016). Nursing workload and occurrence of adverse events in intensive care: A systematic review. 50(4), 679–689. [CrossRef]

- Obwieszczenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 18 stycznia 2022 r. W sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu rozporządzenia Ministra Zdrowia w sprawie standardu organizacyjnego opieki zdrowotnej w dziedzinie anestezjologii i intensywnej terapii. (2022). MIN. ZDROWIA.

- WHO. (b.d.). STATE OF THE WORLD’S NURSING. Pobrano 8 grudzień 2022, z https://apps.who.int/nhwaportal/Sown/Files?name=POL.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 28 grudnia 2012 r. W sprawie sposobu ustalania minimalnych norm zatrudnienia pielęgniarek i położnych w podmiotach leczniczych niebędących przedsiębiorcami. (2012). MIN. ZDROWIA.

- Borzuchowska, M., Kilańska, D., Kozłowski, R., Ilchev, P., Czapla, T., Marczewska, S., & Marczak, M. (2022). The Effectiveness of Healthcare System Resilience during the COVID–19 Pandemic: A Case Study (Nr 2022120242). Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Nurses: A force for change: Improving health systems’resilience. (b.d.). NTERNATIONAL NURSES DAY 2016. https://www.thder.org.tr/uploads/files/icn-2016.pdf.

- Building health systems resilience for universal health coverage and health security during the COVID–19 pandemic and beyond: WHO position paper. (b.d.). Pobrano 31 grudzień 2022, z https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-UHL-PHC-SP-2021.01.

- COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION On effective, accessible and resilient health systems. (2014). EUROPEAN COMMISSION.

| No. | Variable | Nurse-to-patient ratio | Average number of working hours in 24 hours | SD | N | Min | Max | Me |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 1:2** | 24.5 | 3.69 | 33 | 15.3 | 29.1 | 25.2 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 1:2** | 27.1 | 3.22 | 25 | 19.6 | 32.3 | 27.5 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 1:1* | 29.4 | 2.00 | 15 | 25.9 | 33.4 | 29.7 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 1:1* | 26.1 | 1.75 | 12 | 24.1 | 29.4 | 25.9 |

| (5) | Last day ECMO | 1:1* | 20.4 | 7.45 | 17 | 5.8 | 30.2 | 22.0 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 1:1* | 27.8 | 1.86 | 12 | 23.8 | 30.7 | 27.8 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 1:1* or 1: 2** | 26.7 | 1.92 | 27 | 22.8 | 30.2 | 26.5 |

| No. | Variable | Test of averages against a fixed reference value | |||||||

| Me | SD | N | S. E. | t | df | Cohen’s d | P | ||

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 19.0 | 2.82 | 33 | 0.49 | 6.41 | 32 | 1.12 | 0.000000 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 22.6 | 2.71 | 25 | 0.54 | 12.44 | 24 | 2.49 | 0.000000 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 23.6 | 1.76 | 15 | 0.45 | 16.99 | 14 | 4.39 | 0.000000 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 20.7 | 1.22 | 12 | 0.35 | 13.76 | 11 | 3.97 | 0.000000 |

| (5) | Last day ECMO | 15.7 | 7.08 | 16 | 1.77 | -0.14 | 15 | -0.04 | 0.890314 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 23.1 | 2.05 | 12 | 0.59 | 12.15 | 11 | 3.51 | 0.000000 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 21.6 | 1.60 | 27 | 0.31 | 18.57 | 26 | 3.57 | 0.000000 |

| No. | Clinical pathway | Nurse-to-patient ratio | Avg no of working hours in 24 hours | SD | Me | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 1:2** | 19.0 | 2.82 | 20.7 | 14.3 | 23.3 | 33 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 1:2** | 22.6 | 2.71 | 23.3 | 17.0 | 29.7 | 25 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 1:1* | 23.6 | 1.76 | 23.3 | 20.7 | 26.5 | 15 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 1:1* | 20.7 | 1.22 | 20.7 | 18.0 | 22.3 | 12 |

| (5) | Last day in ECMO | 1:1* | 15.7 | 7.08 | 18.4 | 1.59 | 23.9 | 12 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 1:1* | 23.1 | 2.05 | 23.6 | 20.1 | 26.5 | 12 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 1:2* * or 1:1* | 21.6 | 1.60 | 20.7 | 20.1 | 26.5 | 27 |

| Variable | Test of averages against a fixed reference value | ||||||||

| No. | M | SD | N | S. E. | t | df | Cohen's d | P | |

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 19.05 | 2.82 | 33 | 0.49 | -10.86 | 32 | -1.89 | 0.000000 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 22.64 | 2.71 | 25 | 0.54 | -3.21 | 24 | -0.64 | 0.003762 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 23.60 | 1.76 | 15 | 0.45 | -1.71 | 14 | -0.44 | 0.108538 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 20.74 | 1.22 | 12 | 0.35 | -10.36 | 11 | -2.99 | 0.000001 |

| (5) | Last day in ECMO | 15.65 | 7.08 | 16 | 1.77 | -4.93 | 15 | -1.23 | 0.000182 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 23.10 | 2.05 | 12 | 0.592408 | -2.1621 | 11 | -0.62 | 0.053510 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 21.63 | 1.60 | 27 | 0.31 | -8.90 | 26 | -1.71 | 0.000000 |

| No. | Variable | Nurse-to-patient ratio | Avg no of working hours in 24 hours | SD | Me | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 1:2** | 25.6 | 1.90 | 26.2 | 17.4 | 28.9 | 33 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 1:2** | 26.2 | 1.94 | 26.8 | 19.7 | 28.9 | 25 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 1:1* | 27.1 | 0.77 | 27.3 | 25.7 | 28.9 | 15 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 1:1* | 24.0 | 2.96 | 24.8 | 19.6 | 29.0 | 12 |

| (5) | Last day in ECMO | 1:1* | 22.5 | 3.27 | 21.3 | 19.0 | 29.0 | 12 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 1:1* | 23.4 | 4.25 | 24.0 | 15.0 | 29.6 | 12 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 1:2** or 1:1* | 23.2 | 4.82 | 23.7 | 13.1 | 29.6 | 27 |

| Day of hospitalization | Test of averages against a fixed reference value | ||||||||

| No. | Avg | SD | N | SE. | T | df | Cohen's d | P | |

| (1) | Patient admission to the ward | 25.60 | 1.90 | 33 | 0.33 | 4.84 | 32 | 0.84 | 0.000032 |

| (2) | Surgical procedure | 26.16 | 1.94 | 25 | 0.39 | 5.59 | 24 | 1.12 | 0.000009 |

| (3) | Entry to ECMO | 27.10 | 0.77 | 15 | 0.20 | 15.53 | 14 | 4.01 | 0.000000 |

| (4) | 1 day ECMO | 24.00 | 2.96 | 12 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 11 | 0.00 | 0.996353 |

| (5) | Last day in ECMO | 22.53 | 3.27 | 12 | 0.95 | -1.56 | 11 | -0.45 | 0.146988 |

| (6) | exit ECMO | 23.39 | 4.25 | 12 | 1.23 | -0.49 | 11 | -0.14 | 0.629811 |

| (7) | Patient's death | 23.24 | 4.82 | 27 | 0.93 | -0.82 | 26 | -0.16 | 0.417825 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).