Introduction

The birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers (including duodenal and gastric ulcers) was first reported by Susser and Stein in 1962 [

1], and amended in 2002 [

2]. They found that the mortality rates of gastric ulcers in England and Wales increased at the beginning of the 20

th century, reached a peak, and then began to fall in the early 1950s [

1,

2]. They also found that the trends for duodenal ulcers were similar but followed ~5 years behind [

1,

2]. Susser and Stein hypothesized that each generation carried its own particular risk throughout adult life and the fluctuations in the mortality rates of peptic ulcers represented a birth-cohort phenomenon [

1,

2]. Subsequent analyses from Western Europe, North America, and Asia confirmed the presence of this cohort pattern [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Susser and Stein speculated that the First World War and the unemployment in the 1930s roughly fit the fluctuation in this cohort pattern [

1,

2], but the mechanism has never been understood.

In total 13 etiological theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of peptic ulcers over the past 3 centuries [

7], such as ‘

No Acid, No Ulcer’ in 1910 [

8] and

Nerve Theory in 1913 [

9]. In 1950, Alexander proposed

Psychosomatic Theory [

10], where multiple psychosomatic factors, such as bad habits, poor lifestyle, and unhealthy environment, were the cause of peptic ulcers [

11]. Also in 1950, Selye proposed

Stress Theory [

12], in which psychological stress induced by social and natural events, etc. is the cause of peptic ulcers. Although each of the 4 major etiological theories was supported by numerous clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory observations, none of them has ever elucidated the birth-cohort phenomenon, along with many other characteristics and observations/phenomena of the diseases.

All the 4 major etiological theories in history were deemed to be out of date soon after the discovery of

Helicobacter pylori (

H. pylori) in 1982 [

13]. In 1987, Marshall proposed that peptic ulcers are an infectious disease caused by the infection of

H. pylori [

14]. As a result, currently peptic ulcers are widely believed to be an infectious disease caused by

H. pylori [

15]. However, this etiology is controversial and how the bacterium leads to ulceration remains unknown [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The etiological theory of peptic ulcers based on

H. pylori infection was designated as

Theory of H. pylori [

7]. Unfortunately,

Theory of H. pylori cannot explain most of the 15 characteristics and 81 observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers, including 30 of the 36 observations/phenomena associated with the bacterium itself [

7]. Moreover, the use of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and other medications is also considered a cause of peptic ulcers, but in

Theory of H. pylori, the roles of gastric acid and NSAIDs remain elusive [

21,

22,

23]. Marshall himself could not explain the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers [

24]. Starting from

Theory of H. pylori, Sonnenberg proposed a mathematical model to explain the birth-cohort phenomenon in 2006 [

25]. However, this model failed to explain the temporal difference between gastric and duodenal ulcers, along with several other issues [

25]. Thus, the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers has remained an unresolved mystery for 60 years.

In recent years, numerous studies have reported that multiple environmental factors may cause peptic ulcers by inducing psychological stress. In 2013, Kanno et al observed that after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, psychological stress significantly increased the incidence of peptic ulcers in

H. pylori-negative and non-NSAIDs users [

26]. Levenstein’s multivariable analysis in 2015 also found that life stressors, such as socioeconomic status, increased risk for peptic ulcers regardless of

H. pylori infection and NSAIDs use [

27]. Other studies found that peptic ulcers were caused not by

H. pylori [

28], but by environmental factors, such as climate [

29,

30], occupation [

31,

32], air pollution [

33], regional and ethnic differences [

28], industrialization [

28], vacation/holidays [

34], immigration [

35], religion [

36], smoking and alcohol abuse [

37], lifestyle, and recreational habits [

38]. However, the role of environmental factors in peptic ulcers remains unknown, and how they cause the birth-cohort phenomenon has never been elucidated.

To address the challenges, a recently published Complex Causal Relationship (CCR) with its accompanying methodologies [

39] was applied to analyze the existing data, resulting in the birth of a new etiological theory of peptic ulcers,

Theory of Nodes [

40,

41,

42]. This theory integrated

Psychosomatic Theory and

Stress Theory into a new etiology, where peptic ulcers are a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress [

41]. Neither

H. pylori nor NSAIDs are a cause of peptic ulcers but play a role secondary to gastric acid in only the late phase of peptic ulcerations [

40,

41,

42]. This etiology addressed all the controversies and mysteries of peptic ulcers in a series of 6 articles, including all 36 observations/phenomena related to

H. pylori. In the first three articles, 14 characteristics and 71 observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers were elucidated [

40,

41,

42]. This article is the fourth one of the series, focusing on the 72

nd observation/phenomenon, the birth-cohort phenomenon. Since the birth-cohort pattern is featured by the fluctuation curves, this retroactive analysis will deliberate on elucidating the mechanism of the fluctuation curves. Despite two different diseases [

43,

44], gastric and duodenal ulcers share similar mechanisms of the birth-cohort phenomenon. Thus herein, only the fluctuation curves of gastric ulcers are explored, and the temporal difference between gastric and duodenal ulcers will also be elucidated.

Results

Theory of Nodes identified that peptic ulcers are not an infectious disease caused by

H. pylori; clinical observations also found that the infection of this bacterium was not essential for this disease [

20,

46,

47]. Herein the data analyses do not consider

H. pylori infection but focus on environmental factors that may induce psychological stress.

In

Theory of Nodes, peptic ulcers are identified as a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress [

40,

41,

42]. Therefore, there is always a proportion of individuals who are genetically predisposed to peptic ulcers in the population, and due to past life experiences/psychosomatic factors, many individuals have developed hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells in their stomach [

41], or have formed negative life-views [

40]. Thus, this proportion of individuals are “ready-to-ulcerate” individuals and may become ulcer patients if psychological stress is induced. In this case, the annual mortality rates are heavily impacted by stressors, including endogenous personality traits, and exogenous family, social, and natural environmental factors [

41]. Herein all the factors in the literature that may cause an annual mortality rate of peptic ulcers, are classified/differentiated into three categories according to their respective features (

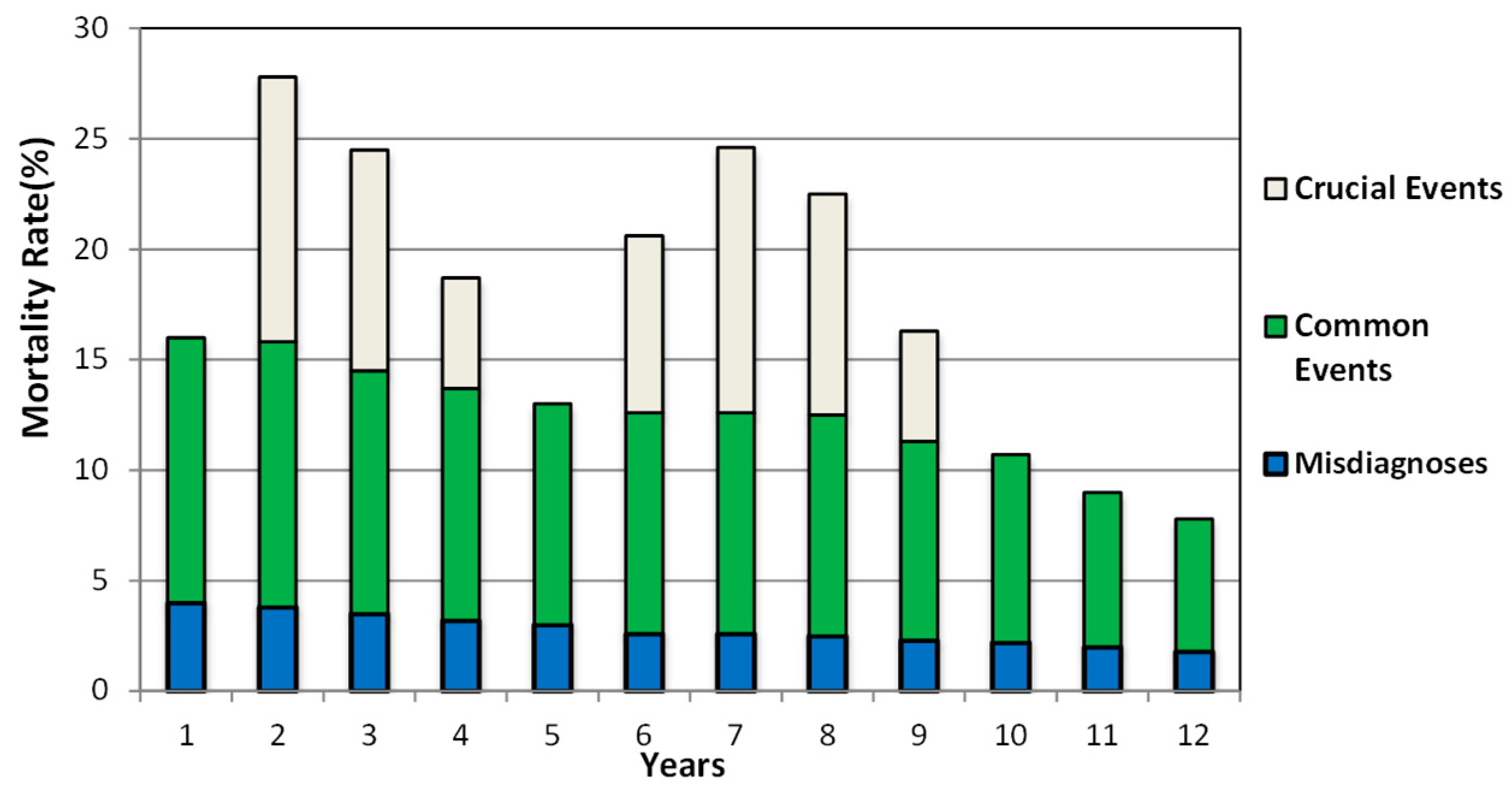

Table 1).

Clinical misdiagnoses occur at a certain frequency [

48,

49], but were more commonly seen in the early 20

th century because diagnostics were not as advanced as they are today. Misdiagnoses increased the overall mortality rate of gastric ulcers and affected statistical results. Therefore, it is regarded as the first category. The second category is termed common events, which may be caused by struggling with personality disorders [

50,

51] or ordinary social and natural environmental factors [

52,

53,

54], such as climate [

29,

30], air pollution [

33], and common life and social events [

55,

56,

57]. Common events arise at a certain rate and cause relatively consistent mortality rates from year to year. For example, there are always a proportion of individuals facing divorce, unemployment, or conflicts with neighbours or family members, resulting in a relatively consistent mortality rate. The third category is referred to as crucial events caused by extraordinary social and natural environmental factors, which happen sporadically and last for an indeterminate amount of time, leading to an uneven mortality/morbidity rate. For example, a war [

58] or an economic crisis [

59,

60] arises unpredictably and is resolved in a period of time. Another example is natural disasters, such as tsunamis or earthquakes [

61,

62], which have short duration but the effects may be felt long-term. All the 3 categories may cause their respective annual mortality rates of peptic ulcers.

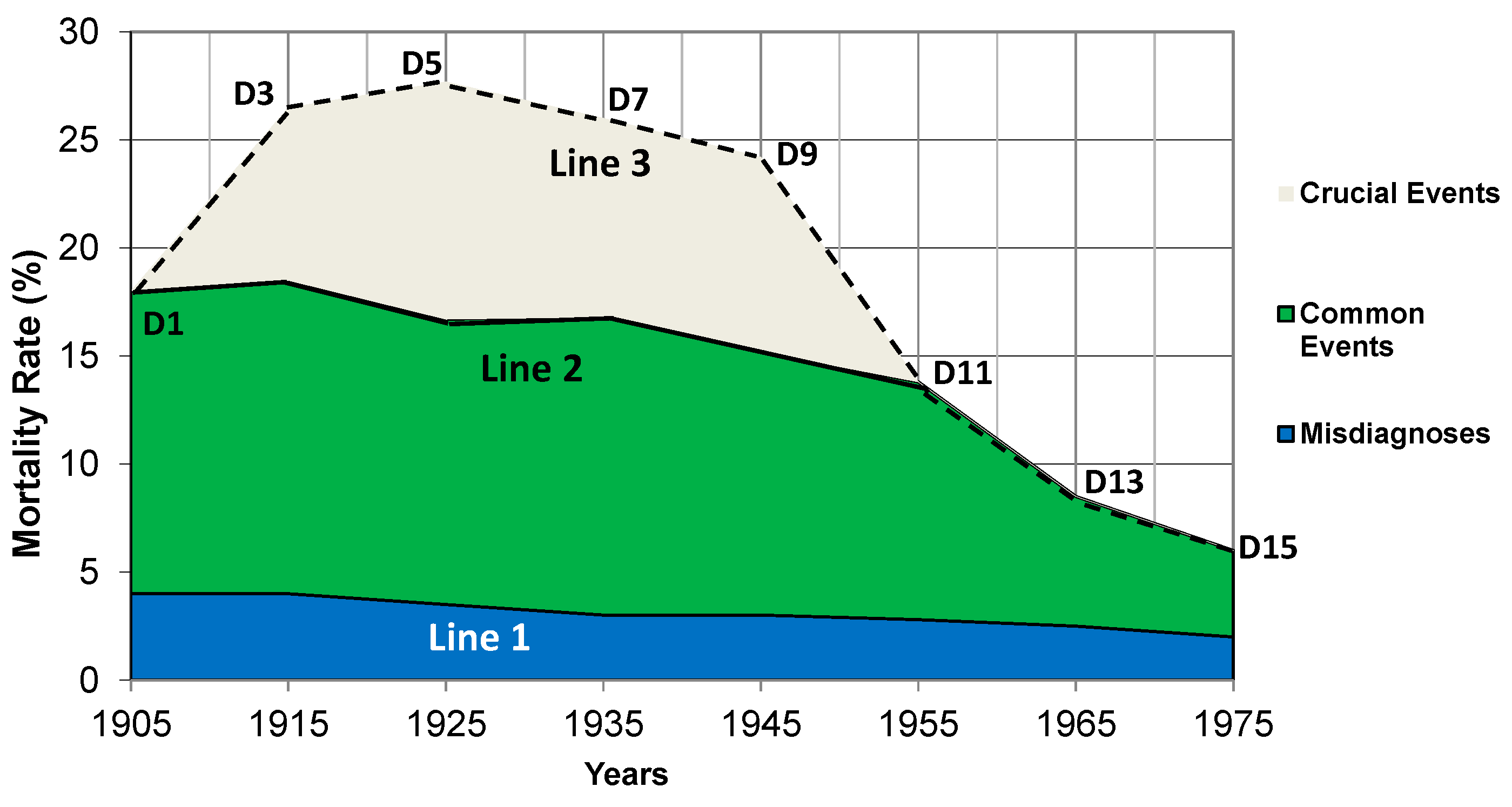

- 2.

Vertical Superposition of the Mortality Ratesof Gastric Ulcers

According to the features of the 3 categories listed in

Table 1, the annual mortality rates caused by clinical misdiagnoses and common events are relatively consistent but declined very slowly due to gradually improved medical conditions, living and sociopolitical environments. In contrast, the annual mortality rates caused by crucial events fluctuate markedly: the presence of a crucial event results in a high annual mortality rate in the year, whereas the absence of a crucial event leads to a zero mortality rate.

The CCR dictates that a life phenomenon is usually the result of additive effects caused by multiple individual factors [

39,

41]. Therefore, a new methodological concept,

Superposition Mechanism, has been derived to elucidate the mechanisms of life phenomena [

39,

41]. Based on this concept, the annual mortality rates (AM) caused by all the three categories are vertically superposed/integrated to calculate the total annual mortality rate of gastric ulcers by the formula AM

Total = AM

Misdiagnoses + AM

Common Events + AM

Crucial Events as illustrated in

Figure 1, where each bar is a sum of the mortality rates on an annual basis of a hypothetical scenario. Notably,

Figure 1 performs differentiation twice (studies annual mortality rates separately and classifies environmental factors into 3 categories) but integration only once (the

Vertical Superposition).

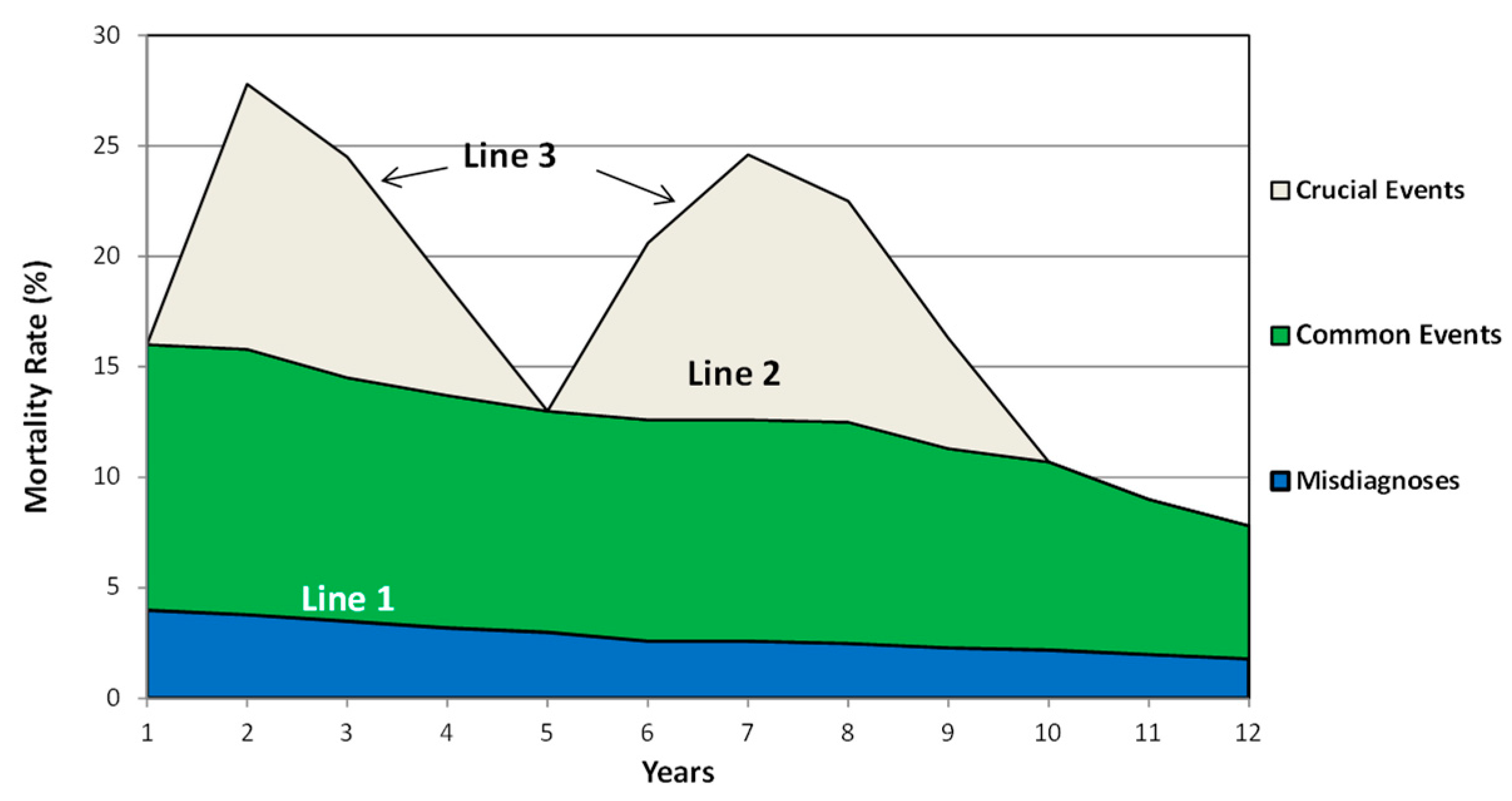

- 3.

Horizontal Superposition to Determine the Trends of Annual Mortality Rates Over Time

Once all the annual mortality rates were calculated, they were horizontally superposed to simulate the temporal trend in the mortality rates of gastric ulcers as shown in

Figure 2. Alternatively, this figure can also be derived by converting the bar graph

Figure 1 into a line graph to provide a chronological view of the annual mortality rates of gastric ulcers. Notably, herein

Figure 2 performed the second integration that has not been completed in

Figure 1 to generate the fluctuations curve caused by all the three categories in

Table 1. The annual mortality rates caused by misdiagnosis and common events fluctuate slightly and therefore, the fluctuations of the total annual mortality rates are primarily due to the rise and fall of the annual mortality rates caused by crucial events (extraordinary social and natural environmental factors), whereas the slight decline after the tenth year is due to the sustained improvements in medical condition and living environment, which result in fewer misdiagnoses and psychological stress. The fluctuation curve with two noticeable peaks in

Figure 2 suggests that, if peptic ulcers are considered a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress [

41], the occurrence and resolution of crucial events (extraordinary environmental factors) dominate the rise and fall trends of the annual mortality rates, signifying a parallel relationship between the psychological impacts of individual environmental factors and the annual mortality rates of gastric ulcers.

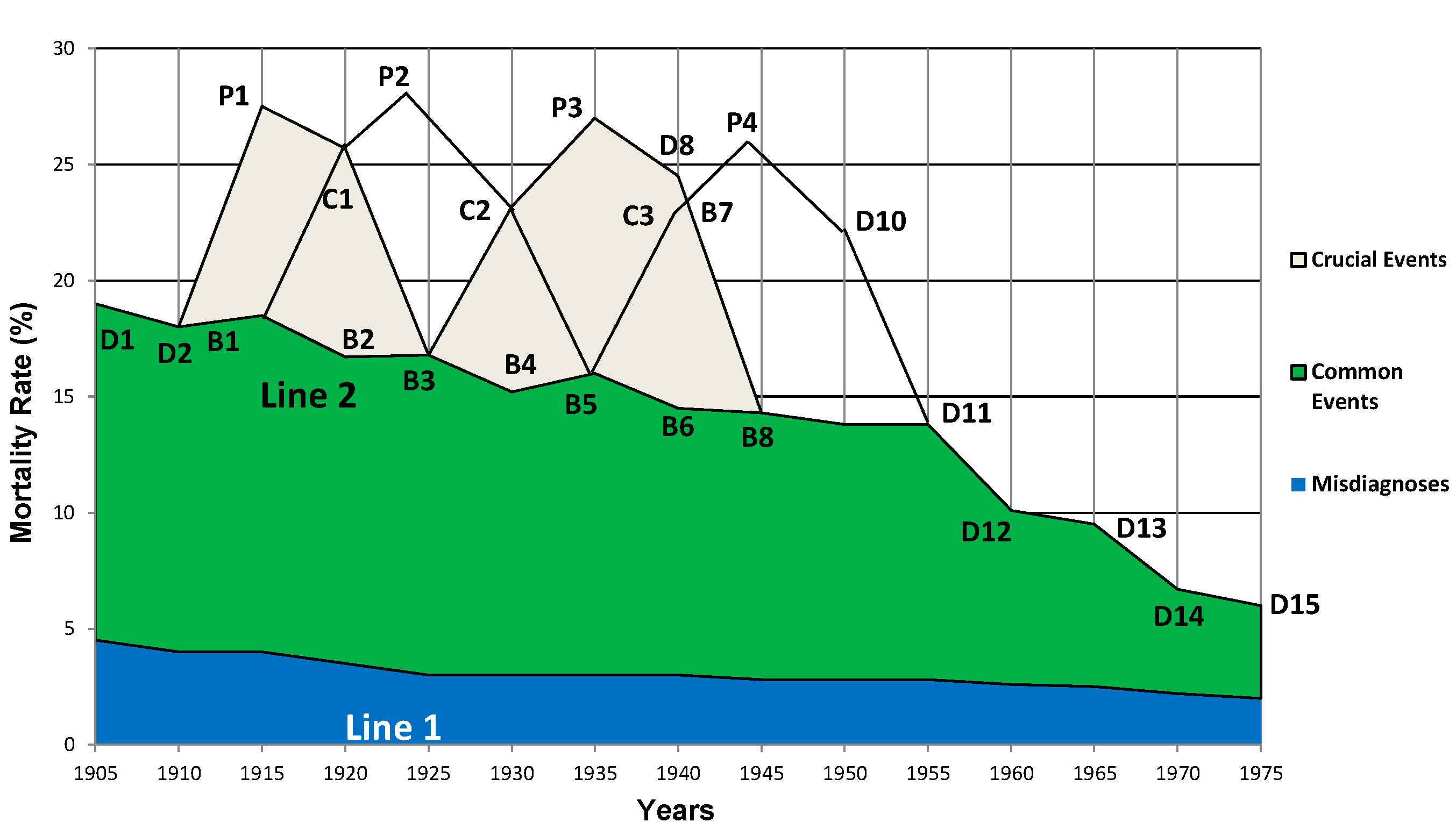

- 4.

Overlapping of Fluctuation Curves Caused by a Succession of Crucial Social Events

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 represent an ideal scenario. However, the reality is usually much more complicated. For instance, in the early 20th century, most European countries were affected by the First World War (1914-1918), rebuilding after the war, the unemployment caused by the economic crisis in the 1930s, and the Second World War (1939-1945), followed by another rebuilding after the War until the early 1950s. As a result, from the 1910s to 1940s, at least four crucial events occurred successively in many European countries, including England and Wales, where the data was collected by Susser and Stein for the birth-cohort phenomenon [

1,

2]. Similar to

Figure 2, each of the 4 individual crucial events caused its own fluctuation curves, and these curves overlap as shown in

Figure 3. Herein, the four curves epitomize the parallel relationship between the psychological impacts of individual environmental factors and the annual mortality rates of gastric ulcers, and they represent the third differentiation in the data analyses. Notably, since multiple crucial events occurred successively, the fall trend (decreased annual mortality rates) due to the resolution of a crucial event overlapped the rising trend (increased annual mortality rates) caused by another crucial event that followed.

- 5.

The calculation of the Total Annual Mortality Rates Caused by all 3 Categories

In the case of a succession of 4 crucial events, the

Vertical Superposition in

Figure 1 was repeated to calculate the total annual mortality rates of gastric ulcers from 1905 to 1975. If there were two crucial events in a given year, the annual mortality rates they caused were superposed by the formula AM

Crucial Events=AM

Crucial Event-1+AM

Crucial Event-2. Assume this scenario: In 1915, the mortality rate as a result of the First World War was 9%, but there were no effects from rebuilding, thus the total annual mortality rate caused by crucial events in this year was 9%. In 1920, the annual mortality rate of peptic ulcers caused by the residual effects of the First World War was 9%, and by rebuilding after the war was 9%, so the total annual mortality rate by crucial events was 9%+9%=18%. The total annual mortality rates caused by crucial events were calculated similarly for all the other years. Subsequently, the total annual mortality rate of a given year was calculated by the formula AM

Total = AM

Misdiagnoses + AM

Common Events + AM

Crucial Events. Then the

Horizontal Superposition described in

Figure 2 was iterated to generate the fluctuation curve on a five-year basis from 1905 to 1975 as shown in

Figure 4. Notably, herein the annual mortality rates caused by all three categories listed in

Table 1 are integrated/superposed three times in two ways (vertical and horizontal) to produce the fluctuation curve of a real scenario in England and Wales, where Susser and Stein collected the data for the birth-cohort phenomenon [

1,

2].

Figure 4 elucidates that after the superposition, the fall trend due to the resolution of a crucial event was counterbalanced by the rising trend caused by another crucial event that followed (as shown in

Figure 3). As a result, both the fall and rise trends caused by two successive crucial events become invisible, and thus, the annual mortality rates from the 1910s to 1940s were maintained at a higher level than other decades.

However, overestimations occurred when the

Vertical Superposition was applied to calculate the total annual mortality rates if there were two crucial events in a year. In 1920, 1930, and 1940, individuals might experience two crucial events and become ulcer patients but could also become patients if they experienced only one of the two events. Thus, some patients might have been counted twice, causing extremely high total annual mortality rates in 1920 (D4), 1930 (D6), and 1940 (D8) as shown in

Figure 4.

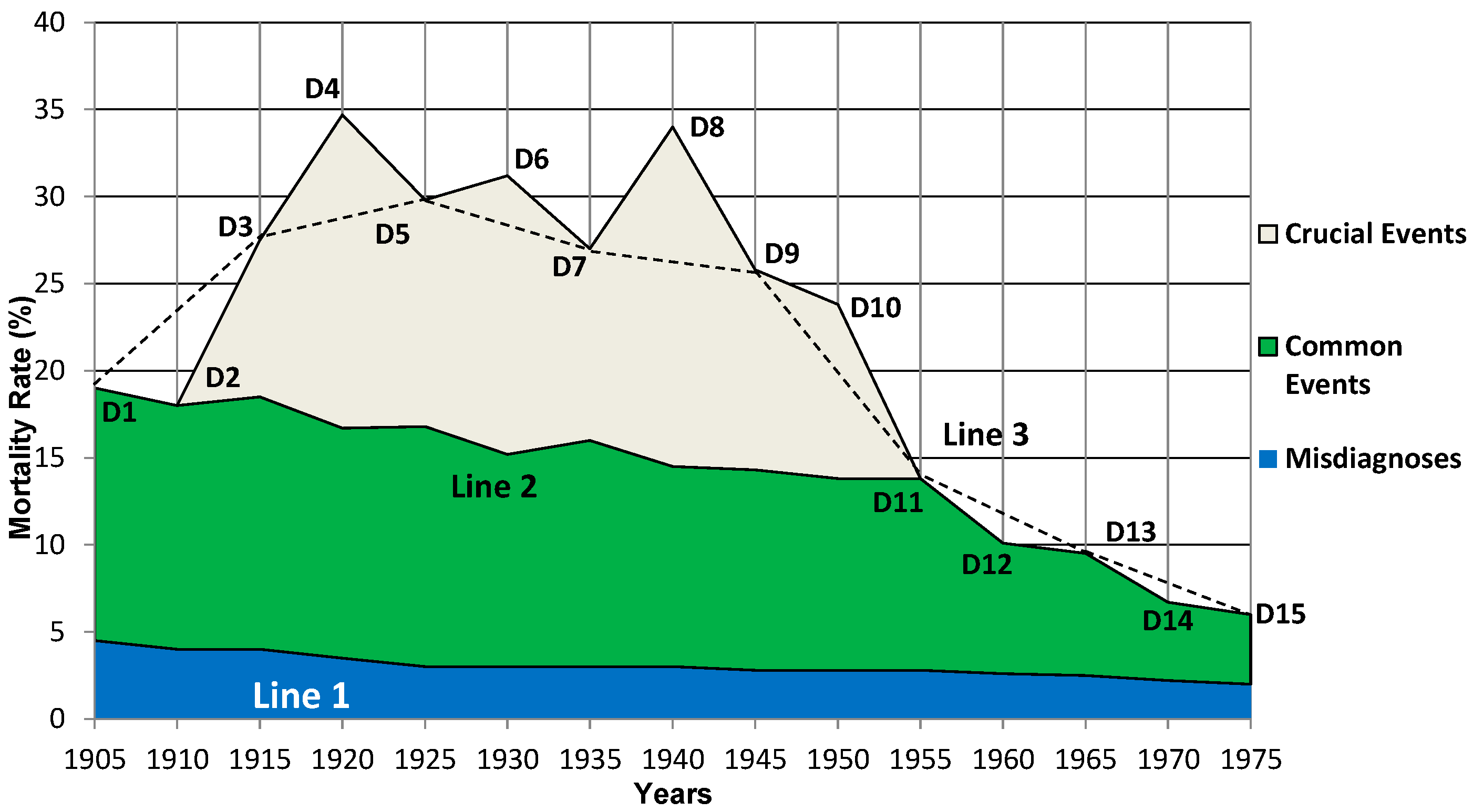

- 6.

Reproduction of the Mortality Fluctuation Curves of the Birth-Cohort Phenomena

Fortunately, Susser and Stein did not investigate the mortality rates in the years 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, and 1970. After the data for these years were removed from the theoretical curve in

Figure 4, one of the fluctuation curves in the birth-cohort phenomenon observed by Susser and Stein is reproduced as shown in

Figure 5. The evolutionary process from

Figure 3 to

Figure 5 suggests that an integration/superposition of the annual mortality rates caused by all the three categories in

Table 1 reproduced a fluctuation curve in the birth-cohort phenomenon. Conversely, a proper differentiation of the fluctuation curves in the birth-cohort phenomenon in

Figure 5 restored the fluctuation curves caused by multiple individual environmental factors as illustrated in

Figure 3, where the psychological impacts of individual extraordinary environmental factors are parallel with the annual mortality rates of peptic ulcers. However, after the integration/superposition, the counterbalance between two successive crucial events made the parallel relationships between the psychological impacts of individual extraordinary environmental factors and the annual mortality rates of peptic ulcers invisible (

Figure 4), indicating the parallel relationships were hidden in the fluctuation curves of the birth-cohort phenomenon. As a result, Susser and Stein observed a continuous high level of annual mortality rates from the 1910s to the early 1950s. In addition, similar to the analysis in

Figure 2, the relatively peaceful living and sociopolitical environments after the Second World War account for the steady decline of the annual mortality rates since the early 1950s.

Notably, the data analyses presented apply to all the age groups in the birth-cohort phenomena. In addition, the analyses can be applied to explain various parameters of peptic ulcers, such as morbidity rates, perforation rates, hospitalization rates, and disability pension rates. These parameters are all interrelated and affected by misdiagnoses, common events, and crucial events. Therefore, the fluctuation curves for all these parameters follow similar temporal trends.

- 7.

Understanding the Details of the Birth-Cohort Phenomenon of Gastric Ulcers

Line 3 in

Figure 5 suggests that if gastric ulcer is considered a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress and if the concept of ‘

Superposition Mechanism’ is used to analyze the existing data, the fluctuation curves in the birth-cohort phenomenon observed by Susser and Stein can be reproduced, especially the curve for the 25-34 age group who experienced the greatest effects from crucial events [

1,

2]. The etiology and methodology are also applicable to all the other age groups: the older the age, the more complex life experiences causing psychological stress, thereby the more susceptible to gastric ulcers. This elucidated Susser and Stein’s finding that ‘the risk of death from both gastric and duodenal ulcers can be seen to rise steadily with age’ [

1,

2].

Figure 5 explicitly elucidated the rise and fall in the mortality rates of gastric ulcers observed by Susser and Stein. The start of the First World War in 1914 explained the sharp rise in mortality rates of gastric ulcers in the early 20

th century. The continuing trend of increase in perforated gastric ulcers until the early 1950s was maintained by a succession of multiple crucial events. The decrease in annual mortality rates in the early 1950s was due to the end of the Second World War followed by the rebuilding after the War, and the steady decline in the late 1950s was a result of sustained improvements in medical treatments, living conditions, and sociopolitical environment. The start and end of crucial events explain the slope observed from 1905 to 1915 (the First World War) and from 1945 to1955 (the Second World War and rebuilding after the war). The generation born around 1885, especially the males, were in their 20s~30s when the First World War broke out in 1914. They experienced all the crucial events from 1914 to the early 1950s in their adult life and were most probably the direct participants, executors, and/or victims. Their unfortunate experiences explained Susser and Stein’s finding that ‘for gastric ulcer in males the generation born around 1885 carried the highest risk’ [

1,

2].

Figure 5 also confirmed Susser and Stein’s speculation that ‘the timing of the First World War and the unemployment of the 1930s roughly fit the fluctuations and the cohorts with the highest peptic ulcer death rates’ [

1,

2].

- 8.

The Mechanism of Temporal Difference between Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

In

Theory of Nodes, three factors, heredity, secondary stressors derived from crucial events, and the hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells in the stomach induced by chronic stress [

41], explain the temporal difference between gastric and duodenal ulcers observed by Susser and Stein [

1,

2].

The importance of heredity in peptic ulcers has been emphasized by clinical observations [

63]. In

Theory of Nodes, individuals susceptible to gastric and duodenal ulcers are two genetically different populations [

40,

41]. Thus, although the whole population experienced the same crucial events simultaneously, individuals with gastric ulcer predisposition may develop gastric ulcers, whereas individuals with duodenal ulcer predisposition may develop duodenal ulcers [

42]. However, stressors for gastric ulcers, such as wars, unemployment, financial crises, catastrophes, loss of family members, and divorce, which are usually short-term and acute, may cause gastric ulcers directly right after or during crucial events [

40]. In contrast, duodenal ulcers are caused by the secondary chronic stressors derived from crucial events, such as laborious work, poor work/living environments, lower social status, or strained family relations, which are usually long-term, cannot cause duodenal ulcers right away due to the chronic psychopathological process of the disease [

41]. As a response to chronic stress, it takes ~5 years to induce the hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells in the stomach [

64,

65], which in turn result in the hypersecretion of gastric acid and eventually, duodenal ulcers. On the other hand, unlike the easy-to-simulate acute stress that induces gastric ulcers [

66,

67], chronic stress that induces duodenal ulcers is difficult to duplicate in labs. As a result, all of the stress-induced ulcers in animal models were gastric ulcers [

63], further supporting the temporal differences between gastric and duodenal ulcers [

40].

Therefore, despite experiencing the same crucial events, some individuals developed gastric ulcers right away, causing increased mortality rates immediately, whereas some others developed duodenal ulcers ~5 years later, resulting in ‘the trends for duodenal ulcers were similar to gastric ulcers but followed approximately 5 years behind [

1,

2]’.

Discussion

Despite 13 etiological theories being proposed in history [

7], the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers has remained an unresolved mystery for 60 years. The application of the CCR with its accompanying methodology proposed in 2012 birthed

Theory of Nodes [

40,

41,

42], which addressed all the controversies and mysteries of peptic ulcers in a series of 6 articles, including the birth-cohort phenomenon in this fourth article [

40,

41,

42,

68,

69].

Theory of Nodes attributes its success to a definite etiology of peptic ulcers, as well as an innovative methodological concept,

Superposition Mechanism. Significantly, the explanation of the birth-cohort phenomenon herein identified a causal role of environmental factors in peptic ulcers.

Unequivocally, an etiological theory proposing the correct cause of peptic ulcers should be able to explain all the characteristics and observations/phenomena of the disease. However,

Theory of H. pylori cannot face the challenges of the 15 characteristics and 81 observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers [

7], indicating that

H. pylori infection may not be the cause of peptic ulcers. Interestingly, herein the birth-cohort phenomenon was elucidated without considering

H. pylori infection, further suggesting that this bacterium may not be the cause of peptic ulcers [

17,

20,

70,

71,

72]. The data analyses elucidated that it is not

H. pylori infection, but the psychological impacts induced by environmental factors that dominate the rise and fall trends of the annual mortality rates of peptic ulcers. Thus, it is not surprising that starting from

H. pylori infection, neither Marshall nor Sonnenberg could explain the birth-cohort phenomenon [

24,

25], along with the majority of the 15 characteristics and 81 observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers.

- 2.

The Birth-Cohort Phenomenon has Implicated a Causal Role of Environmental Factors in Peptic Ulcers

Notably, when the birth-cohort phenomenon was first observed in 1962, Susser and Stein speculated that the First World War (1914-1918) and the unemployment in the 1930s roughly fit the fluctuation curves [

1,

2], suggesting that this cohort pattern has implicated a causal relationship between extraordinary environmental factors/crucial events and peptic ulcers. However, modern medicine rarely attributes the cause of disease to the invisible, intangible, and incorporeal psychological stress caused by environmental factors. Instead, it gets used to attribute the cause of disease to visible, tangible, and corporeal structural abnormalities within the human body, such as gene mutations, infectious microbes, or other aberrant biological molecules. As a result, Susser and Stein’s finding was not supported by the mainstream of etiological concepts in modern medicine. In contrast, despite leading to more controversies and mysteries [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20],

Theory of H. pylori perfectly matched the etiological concepts of modern medicine, therefore

H. pylori infection was widely believed to be the cause of peptic ulcers soon after the discovery of the bacterium in 1982 [

73,

74,

75]. Consequently, very little progress has been made in peptic ulcer research over the past 35 years.

- 3.

Environmental Factors Cause the Birth-Cohort Phenomenon by Superposition Mechanism

The explanation of the birth-cohort phenomenon herein supported the etiology of peptic ulcers elucidated in

Theory of Nodes, where peptic ulcers are a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress [

41]. This etiology dictates that any factor inducing psychological stress, including various environmental factors, may cause peptic ulcers, suggesting environmental factors play a causal role in the disease. Therefore, the occurrence and resolution of crucial events (extraordinary environmental factors) dominate the rise and fall trend of the fluctuation curves of annual mortality rates. This parallel relationship reflects a causal role of extraordinary environmental factors in peptic ulcers, which was hidden in the fluctuation curves of the birth-cohort phenomenon and surfaced after 3 times of differentiations as illustrated in

Figure 3. Interestingly, a parallel relationship (between the psychological impacts of ordinary environmental factors and the monthly incidence of the disease) surfaced after differentiating the fluctuation curves in the seasonal variation of peptic ulcers twice in the fifth article of the series [

69]. Thus, ordinary environmental factors, such as climate, occupation, air pollution, regional and ethnic differences, industrialization, immigration, and religion, also play a causal role in peptic ulcers. In the birth-cohort phenomenon, although the ordinary social and natural environmental factors did not dominate the rise and fall trends of the fluctuation curves, the annual mortality rates they caused accounted for the steady decline in the fluctuation curves since the early 1950s. Therefore, both the birth-cohort phenomenon and seasonal variation are compelling evidence to support a causal role of environmental factors in peptic ulcers, which can be revealed by proper differentiation operations. Further, the fluctuation curves can be reproduced by integration operations, suggesting that multiple (ordinary and extraordinary) environmental factors caused the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers via

Superposition Mechanism.

It is worth mentioning that without pre-existing hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells in the stomach and the negative life-view caused by psychosomatic factors in early life, psychological stress induced by environmental factors alone cannot cause peptic ulcers. Thus, the explanation surrounding psychological stress in this research does not conflict with the etiology proposed in Theory of Nodes, where peptic ulcers are a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress.

- 4.

A Viable Analytical Method is Indispensable to Elucidate the Birth-Cohort Phenomenon

Although

Stress Theory proposed by Hans Selye in 1950 emphasized the causal roles of stressful life events in peptic ulcers [

7], it has never explained the birth-cohort phenomenon over the past 60 years, indicating that a correct etiology alone is inadequate to elucidate this phenomenon. The data analyses herein highlighted the significance of a viable analytical method. Newton’s success in calculus suggests that a complete analysis should include two inverse operations, namely differentiation and integration. However, due to a reductionist approach, which attempts to explain a system in terms of its parts [

76], modern medicine only differentiates/divides the human body into many small pieces and studies each piece separately, but rarely attempts to integrate the small pieces into the original whole human body, making numerous studies only half-way done. Consequently, the majority of life phenomena remain unresolved mysteries, including the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers. In contrast, this study performed both the differentiation and integration processes as Newton did in Physics: the differentiation revealed a causal role of environmental factors in peptic ulcers, whereas the integration elucidated that multiple environmental factors cause the birth-cohort phenomenon by

Superposition Mechanism, suggesting that both of the two inverse operations are indispensable methodology in life science and medical research. Further, surrounding the mechanism discovered herein, all the details of the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers were fully understood for the first time in history. The validity showcased herein suggests that the

Superposition Mechanism might be a significant complement to the current methodology in life science and medicine, and therefore, is indispensable for a full understanding of many life phenomena and diseases.

- 5.

Limitations

A potential limitation is that there might be many crucial events between the 1910s and 1940s in England and Wales, where the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers was observed by Susser and Stein. However, to simplify the data analyses, herein only four well-known crucial events were selected to exemplify the application of the Superposition Mechanism. The analyses suggest that, to elucidate the cohort patterns in a specific location, the greater the details of the local environmental factors are included, the more accurate the fluctuation curves that can be reproduced for a full understanding of the epidemiological observations.

Second, the key analytical method applied herein, Superposition Mechanism, is a thought process opposite to the routine reductionist approach in modern medicine. Although the application showcased herein is as easy as a simple addition, only factors with commonalities can be integrated/superposed/added up. In this study, all the mortality rates are of peptic ulcers and therefore, they can be superposed to generate fluctuation curves. Moreover, there might be many ways to superpose research data but, in this study, only the simplest two ways (vertical and horizontal) were performed for a full understanding of the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers. All these indicate that the application of this methodological concept is not a simple mathematical addition but demands greater intelligence.