Introduction

Orthodontics is a recognized clinical dental

specialty and undergraduate dental programs worldwide aim to equip

undergraduate students with the core knowledge and skills in orthodontics to be

able to provide safe dental care to patients. However, there appear to be

significant variations in the scope of orthodontics in undergraduate dental

education not only globally but also amongst universities in the same country.

These variations may lead to marked differences in the curriculum content,

teaching methods and competency assessments (1). Consequently, dental graduates

from different dental schools may demonstrate considerable disparities in the

skills to assess, manage and refer orthodontic patients in general dental

practice settings.

General dental practitioners (GDPs) act as

gatekeepers for provision of specialist dental services as GDPs are the main

source of referral to dental specialists (2). In addition, it has also reported

that up to 72% of the general dentists surveyed were performing some form of

orthodontics, and that 38% of those cases involved clear aligners (3).

Therefore, the recognition, timely referral, and optimal management of

orthodontic patients is heavily dependent on GDPs. Amongst other factors,

undergraduate dental education in orthodontics, has a huge influence on the

approach of GDPs to deal with orthodontic patients and it is crucial to achieve

a broad consensus on orthodontic curricula for optimal and safe patient care by

the GDPs.

Regulators of dental education in different regions

of the world have outlined the learning outcomes (LOs) for undergraduate

orthodontic education. The Association for Dental Education in Europe (ADEE)

expects graduating European dentists to be competent in diagnosing orthodontic

treatment needs and contemporary treatment techniques (4).The Commission on

Dental Accreditation (CODA) on standards of malocclusion and space management

formed by the American Dental Association (ADA) requires pre-doctoral graduates

to be able to provide comprehensive care experiences to patients commensurate

with competence in all components of general dentistry practice (https://coda.ada.org/standards).

The generic description of Los by ADEE and CODA leave a considerable room for

interpretation which may lead to variations in which academic programs develop

and deliver their undergraduate orthodontic curricula and assessments.

There is limited published literature on the

content, structure and delivery of orthodontic curricula by dental schools

worldwide which makes it difficult to evaluate the variations at the level of

individual programs. Evidence from dental schools in the US suggests that the

knowledge and clinical experience of students tend to vary programs, and,

presumably, so do competencies and outcomes assessment (5). The General Dental

Council in the United Kingdom appears to provide a more focused description of

the Los for undergraduate orthodontic curriculum. In the UK, dental graduates

are expected to be competent in assessing orthodontic treatment needs, provide

emergency orthodontic treatment, refer patients to orthodontic specialists and

be able to explain contemporary orthodontic treatment options to patients (https://www.gdc-uk.org/).

In spite of clearly defined undergraduate orthodontic LOs by the GDC, studies

on UK dental students have reported lack of clinical experience in assessing

patients, applying the index of orthodontic treatment needs (IOTN) and making

referrals (6).

Given the apparent lack of consistency in

undergraduate orthodontic curricula, a fundamental question to inform the

refinement of orthodontic curricula is “What knowledge and skills must a

general dentist have to properly manage their patients with malocclusion and/or

skeletal problems?” (7, 8). Opposing views on the scope of undergraduate

orthodontic education are reported in the literature ranging from those who

favor restricting undergraduate orthodontic teaching to the basics (9) to those

who support a more comprehensive teaching and training (10).

The present scoping review was aimed at

investigating commonalities and variations in the learning outcomes, curriculum

content, assessment methods and competencies in undergraduate orthodontic

curricula globally.

Methods

Study protocol and registration

This scoping review adopted the updated

methodological guidance proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute and reported in

accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and

Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The protocol was

registered in Open Science Framework (Registration DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/6AWSEI)

Research Question

This review posed the following question:

What are the learning outcomes, curriculum content

and competency assessment methods for undergraduate curricula in Orthodontics?

A population, concept, context (PCC) framework was

used to answer the research question as explained below:

Population: Content experts from university

setting, Undergraduate dental students and newly graduated dental

practitioners.

Concept: Orthodontic curriculum, learning outcomes

and methods of assessments.

Context: Orthodontic competencies of undergraduate

students

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria applied for this scoping

review was based on studies PCC strategy and is summarized below:

Inclusion criteria

Studies that included Undergraduate dental students, general dental practitioners with a pre-doctoral degree and teaching experts as participants.

Studies that included Orthodontic curriculum, Orthodontic learning outcomes, Assessment methods as objectives of interest.

Cross sectional studies, expert panel opinions

Published from 1998 to 2022

Published in English

Exclusion criteria

Studies that included Post-graduate or graduate students or those focused on post graduate or graduate education, specialty practices

Studies not including orthodontic discipline

Studies published in languages other than English

Search strategy

The search strategy comprised of a combination of

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords for PubMed and index terms

pertaining to the other databases. The detailed search string is (((clinical

competence) AND (orthodontics)) AND (education*)) AND (teaching).

Selection of sources of evidence

All the identified articles were imported into a reference management software (desktop version of EndNote®, version X9; Clarivate Analytics, London UK). After removal of duplicates, two reviewers (S.R and E.A) independently screened the articles based on title and abstracts using Rayyan Systematic Review Screening Software (

https://www.rayyan.ai). The studies whose abstracts fit the eligibility criteria were selected for full text reading for the final selection. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data charting process

Data charting was performed by 2 reviewers (S.R and E.A) independently using a standardized data charting sheet to capture the essential data items.

Data items

The data items included the author’s name, year of publication, title, study design, setting, objectives, sample size, population, data collection tool and conclusion.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was not applicable to this scoping review as no new data was generated for this study.

Results

Study Selection

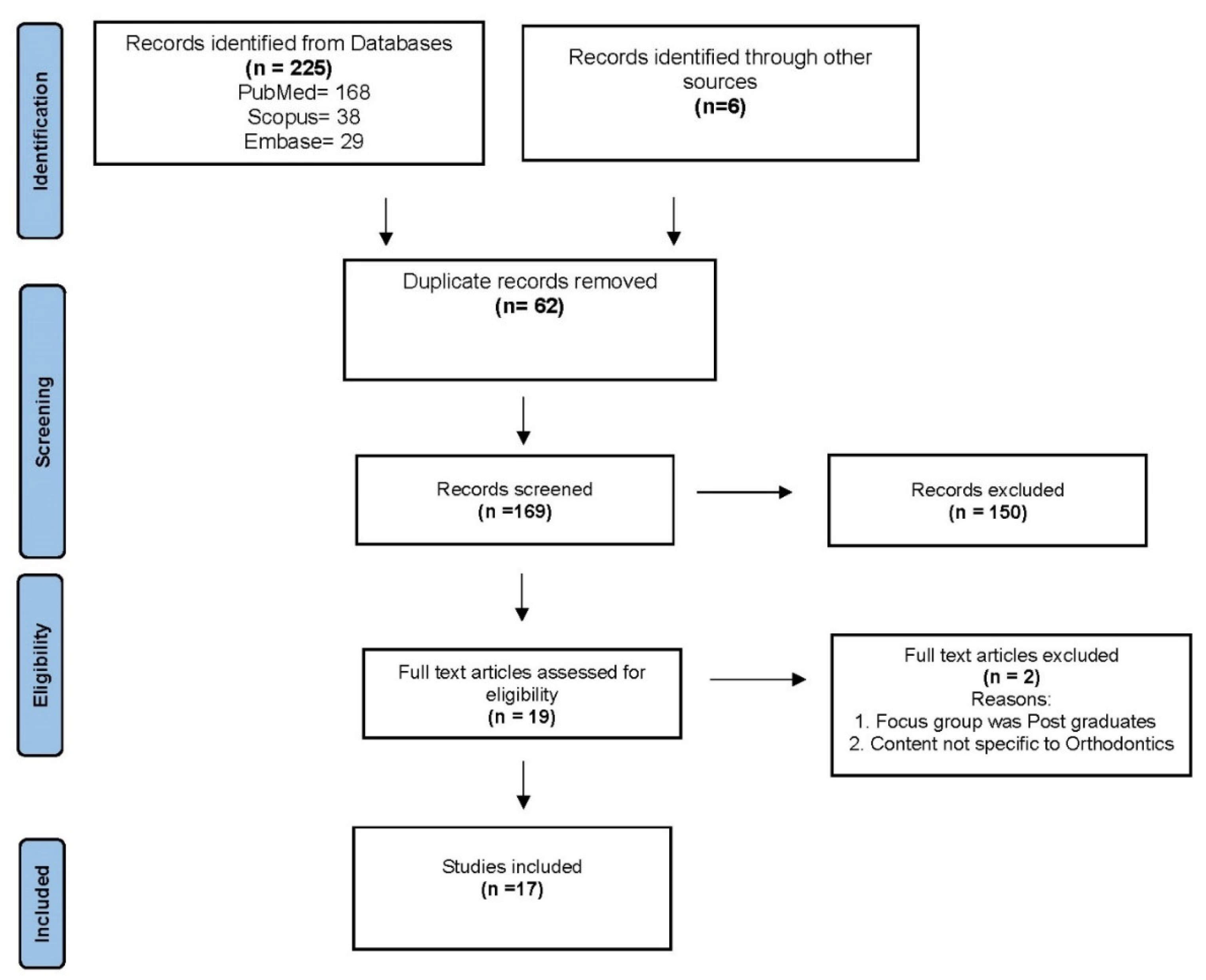

The results of search and study selection are shown in

Figure 1. The total number of reports identified was 231 (225 from the databases and 6 reports from grey literature). After removal of 62 duplicates, 169 reports were included in the title and abstract screening. Of these, 147 from the databases and 3 from grey literature were excluded, and only 19 reports (13 from the databases and 3 grey literature) were considered for full text screening. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were assessed for inclusion by the two reviewers, of which 2 (from the databases) were excluded for various reasons. The following studies were excluded:

Reason for exclusion: The article focusses on post graduate educational assessments

- 2.

Patel et al. (2018) (12) “Assessment in a global context: An international perspective on dental education”.

Reason for exclusion: The article does not specifically relate to Orthodontics

Finally, 17 articles (1, 5, 13-27) were included for qualitative analysis.

Study Characteristics

This scoping review included 13 cross-sectional surveys (1, 13, 14, 16-19, 21-25, 27), three expert panel proceedings (2, 5, 26) and one discussion paper (20). Seven of the included studies investigated undergraduate orthodontic learning outcomes and course content (1, 5, 15, 23, 25-27) , eight studies investigated competency of undergraduate dental students (13, 17-19, 21-24), three studies investigated assessment tools as primary outcome (14, 16, 20), one study investigated LOs as primary outcome and assessment tools as an additional outcome (1) while another study evaluated learning outcomes and course content in addition to competency of dental students (23). The main characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. The main findings of the studies included in this review are discussed under three themes below.

Theme I: Undergraduate orthodontic curricula: Learning outcomes and course content

Article 1:-The current state of predoctoral orthodontic education in the United States (Kwo et al., 2011) (1)

This study assessed predoctoral orthodontic education in the United States. Twenty-nine program directors (53 percent) completed an online survey. The outcome of this survey showed that the number of curriculum hours devoted to teaching orthodontics during the predoctoral years varies greatly between schools. Also, variations in curriculum content in predoctoral orthodontic programs was observed. Less than one half (48 percent) of the programs require students to treat orthodontic patients (56 percent fixed appliances, 41 percent functional and 51 percent clear aligners). Two-thirds of the responding programs considered the current time allocated for predoctoral orthodontic clinical education at their institutions to be adequate.

Article 2: Expert Consensus on Growth and Development Curricula for Predoctoral and Advanced Education Orthodontic Programs (Ferrer et al. 2019) (15)

This study aimed to obtain expert consensus on growth and development topics in predoctoral education programs in orthodontics and to determine the level of cognition on the subtopics necessary to demonstrate learner competence. They determined the mean level of cognition for predoctoral education was understand.

Articles 3: Expert consensus on Didactic Clinical Skills Development for orthodontic curricula (Ferrer et al., 2021) (5)

This study aimed to determine the curriculum content and competency in predoctoral orthodontic programs. A focus group, composed of five full-time faculty members from three orthodontic programs was formed to develop a predoctoral orthodontic curriculum using a modified Delphi approach. Their results identified that all topics proposed by a focus group were necessary, except for appliances. They concluded that be deemed competent, new graduates must demonstrate knowledge in the cognitive domain of “understand” including the principles of application of orthodontic appliances.

Article 4: Orthodontic teaching practice and undergraduate knowledge in British dental schools (Rock et al., 2002) (23)

This study was conducted to evaluate current orthodontic teaching practice in the undergraduate curricula at British dental schools and to test the abilities of undergraduate students according to the requirements of the GDC regulations. Data was collected by means of a questionnaire sent to each dental school in 1998 was compared with similar data from 1994. The orthodontic knowledge and treatment planning ability of students was assessed by a multiple-choice examination paper completed by a random 10% sample of students from each dental school. They reported that the teaching of fixed appliances had increased considerably between 1994 and 1998. Students scored well on questions that tested basic knowledge but much less well when they were required to apply that knowledge. They concluded that undergraduate orthodontic training should concentrate on diagnosis and recognition of problems rather than on providing limited exposure to treatment techniques

Article 5: A Survey of Undergraduate Orthodontic Education in 23 European Countries (Adamidis et al 2000) (25)

This paper reports on a survey of teaching contents of the undergraduate orthodontic curriculum in European countries in 1997, and on whether or not these countries set a formal undergraduate examination in orthodontics. A questionnaire was mailed to all members of the EURO-QUAL BIOMED II project (23 countries). The results showed that the time allocated to orthodontic teaching including theory, clinical practice, laboratory work, diagnosis, and treatment planning varied widely. In general, clinical practice and theory were allocated higher number of hours, whilst diagnosis, laboratory work, and treatment planning were reported as receiving relatively less time. Removable appliances were reported to be taught in 22 of the 23 countries, functional appliances in 21 countries and fixed appliances in 17 countries. An undergraduate examination in orthodontics was reported by 20 countries.

Article 6: Developing Faculty Consensus for Undergraduate Orthodontic Curriculum (Bashir et al 2017) (26)

This is a qualitative study aimed to develop faculty consensus of orthodontic learning outcomes associated with knowledge and skills of “Treatment” required for undergraduate students in Pakistan. Learning outcomes related to skills were formulated in the form of a questionnaire and sent to study participants. Using a five-point Likert scale. The orthodontic faculty agreed that undergraduate students must have skills of history taking, oral examination, x-ray, and removable appliances.

Article 7: Orthodontic curriculum in Saudi Arabia: Faculty members’ perception of clinical learning outcomes ( Al Gunaid et al. 2021) (27)

This study aimed to assess the perception of orthodontic staff members around clinical LOs of the undergraduate orthodontic curriculum with a focus on dental schools in Saudi Arabia. Twenty-three LOs were formulated, all of which were associated with skills required in the undergraduate orthodontics course. Orthodontic staff members were invited to provide their opinion regarding the curriculum using a Likert scale, whereby participants could answer each question on a scale from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” Sixty-one teaching staff members agreed to partake in this study. The highest level of agreement among the participants pertained to conducting systematic orthodontic intraoral and extraoral examinations (100%), followed by explaining causes for space loss (98.3%). Around 67.1% of the academics did not support dental students to undertake fixed appliance therapy.

Theme II: Assessment methods in undergraduate orthodontic curricula

Article 1:-The current state of predoctoral orthodontic education in the United States (Kwo et al., 2011) (1)

This study assessed predoctoral orthodontic education in the United States. Marked variations in methods of assessment in predoctoral orthodontic programs was found. All schools reported using written examination for assessment. Laboratory and clinical examinations were reported to assess undergraduate students in 74 percent and 65 percent respectively. Only 27 percent of schools were using the OSCE in orthodontics.

Article 2:- A Process for Developing Assessments and Instruction in Competency-Based Dental Education (Lipp 2010) (20)

This paper describes the process of assessments in competency-based dental education using an orthodontic module as an example. However, this paper is related to strategic planning of competency-based assessments rather than orthodontic assessments per se.

Article 3:- Test-Enhanced Learning in Competence-Based Pre-doctoral Orthodontics: A Four-Year Study (Freda 2016) (16)

This study evaluated the impact of test-enhanced instructional approach on competence in diagnosis and management of dental and skeletal malocclusion among third year dental students at the New York University College of Dentistry. It reported improved performance of students in terms of’ diagnosis of malocclusion and treatment planning with the test-enhanced instructional method despite the pass rates being the same.

Article 4:- Recognition of malocclusion: An education outcomes Assessment (Brightman 1999) (14)

This paper aimed at assessing the outcome of undergraduate orthodontic education in School of Dentistry at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. A test tool was employed to ascertain the abilities of predoctoral students in diagnosing malocclusion by presenting records of seven children with malocclusion. In addition, students’ knowledge was tested using orthodontic questions chosen from national board examinations. The results revealed only slight differences among the fourth year and first year undergraduate students, demonstrating the current assessments methods are not appropriate to measure dental students’ diagnostic and referral skills . This study underscores the need for increased clinical training to develop competence in the diagnosis and referral of malocclusions.

Theme III: Competency of undergraduate dental students

Article 1: Preparedness of undergraduate dental students in the United Kingdom: a national study (Ali et al., 2017) (13)

They evaluated the self-perceived preparedness of final year dental undergraduate students in the United Kingdom. An online preparedness assessment scale was sent to dental undergraduate students in their final year by email. The key finding relevant to the present study was that participants felt under-prepared to assess orthodontic treatment needs of patients.

Article 2: The undergraduate preparation of dentists: Confidence levels of final year dental students at the School of Dentistry in Cardiff (Gilmour 2016) (17)

This study investigated the self-reported confidence and preparedness of final year undergraduate students in undertaking a range of clinical procedures. A questionnaire was distributed to final year dental students at Cardiff University, six months prior to graduation. Eighty percent of dental students ‘felt unprepared for the clinical work presented’. Confidence was lowest for the ‘design/fit/adjustment of orthodontic appliances. The authors concluded that complex procedures that were least practiced scored the lowest in overall mean confidence.

Article 3: Does Reflective Learning with Feedback Improve Dental Students’ Self-Perceived Competence in Clinical Preparedness? (Ihm 2016) (18)

This study aimed to explore whether reflective learning with feedback enabled dental students to more accurately assess their self-perceived levels of preparedness on dental competencies. Over 16 weeks, all third- and fourth-year students at a dental school in the Republic of Korea took part in clinical rotations that incorporated reflective learning and feedback. Following this educational intervention, the participants self-reported on clinical competence. The results showed that the participants were least confident in providing orthodontic care.

Article 4: Dental students’ experiences of treating orthodontic emergencies – a qualitative assessment of student reflections (Jones, 2015) (19)

This study aimed to explore dental student experiences of treating orthodontic emergencies within a teaching institution. This study was designed as a single-center evaluation of teaching based in a UK university orthodontic department. The participants were fourth-year dental students who treated orthodontic emergency patients under clinical supervision as part of the undergraduate curriculum. Student logbook entries for one academic year detailing the types of emergencies treated were analyzed. The results showed that the majority of dental students (69%) were confident in managing orthodontic emergencies. The overall conclusion was that theoretical knowledge supplemented by exposure to a range of clinical problems within a supported learning environment made students feel more confident

Article 5: Undergraduate training as preparation for vocational training in England: a survey of vocational dental practitioners’ and their trainers’ views (Patel et al., 2006) (22)

This study aimed to identify areas of relative weakness in dental undergraduate education that could influence the future training needs of vocational trainees (VTs) using structured postal questionnaires. They found that a large proportion of VTs and their trainers felt that undergraduate training in orthodontics had not prepared them adequately for VT.

Article 6: Orthodontic competency in predoctoral education in American dental schools (Oesterle and Belanger 1998) (21)

The aim of the study was to investigate the impact of competency-based education approach in predoctoral orthodontic education. A questionnaire was mailed to orthodontic departments in 53 dental schools in USA. Only 61% schools evaluated the clinical competency in orthodontics mostly by daily clinical evaluations. Only 24% used a summative competency examination which consisted of a written examination, an oral examination, or both. Some schools also evaluated student performance on specific procedures such as fitting bands while others evaluated patient diagnoses, treatment planning. Approximately 16% of those responding did not evaluate orthodontic competency. The study recommended that predoctoral orthodontic education should focus more on skills to diagnose and “manage” orthodontic patients and less on providing active treatment.

Article 7: Competence profiles in undergraduate dental education: a comparison between theory and reality (Koole et al.) (24)

This study aimed to investigate whether a competence profile as proposed by academic- and clinical experts is able to represent the real clinical reality. A questionnaire was developed including questions about gender and age, perception about required competences. A total of 312 questionnaires were completed. All competences in the European competence profile were rated between 7.2 and 9.4 on a 10-point scale. Restorative dentistry, prosthodontics, endodontics, pediatric dentistry and periodontology were reported to be the most important domains in undergraduate education. In regard to orthodontics, assessment of patients’ treatment needs was the key skill required during undergraduate education.

Article 8:- Orthodontic teaching practice and undergraduate knowledge in British dental schools (Rock et al. 2002) (23)

The orthodontic knowledge and treatment planning ability of students was assessed by a multiple-choice examination paper completed by a random 10% sample of students from each dental school. Students scored well on questions that tested basic knowledge, but scores were low for questions testing application of knowledge to clinical problem-solving. The findings of this study suggest that undergraduate orthodontic training should be focused on recognition and diagnosis of problems rather than on providing limited exposure to treatment techniques.

Discussion

There is limited research on the structure and delivery of orthodontic curricula in undergraduate dental education. The results of this study highlight marked variations in the LOs, curriculum content, competencies and assessments of undergraduate orthodontic curricula not only at a global level and regionally but also in individual countries with institutions working under a single regulator. These findings underscore the need to revisit undergraduate orthodontic curricula to improve consistency and improve public confidence regarding the remit and competence of GDPs in providing orthodontic assessment and management. Dental institutions and regulators need further work to achieve constructive alignment in the orthodontic curricula and the intended outcomes, the teaching methods used, and the methods used to assess competence of undergraduate dental students (28) .Such an approach can help to achieve parity in the scope of orthodontic services provided by GDPs in primary care settings.

The findings of this scoping review corroborate with previous studies on predoctoral students in the USA which have identified marked variations in the orthodontic curricula, teaching methods, clinical exposure, competencies and assessments of students in dental schools across the USA (1, 21). Similar findings have been reported in a previous study involving 23 European dental schools (25). The orthodontic competencies for European dentists outlined by ADEE require dental graduates to be able to diagnose orthodontic treatment need and be “competent with contemporary treatment techniques” (4).Orthodontics is a specialized field and it may be unrealistic to achieve competence in contemporary orthodontic treatment needs during undergraduate dental education. It may be argued that specialized postgraduate training in orthodontics is also aimed at achieving the competence in contemporary orthodontic treatment techniques and expecting the undergraduates to achieve the same appears to blur the boundaries between the remit of GDPs and specialist orthodontists. It may be difficult for dental institutions to achieve the orthodontic LOs defined by ADEE in the limited time available for clinical training in undergraduate dental programs. It is suggested that ADEE may revisit the LOs related to orthodontics and elaborate further on competence in contemporary treatment techniques to enhance clarity for education providers.

The orthodontics LOs for undergraduate dental students defined by the GDC appear to be focused and easy to interpret (GDC, 2015). However, previous studies on UK dental students and new graduates have shown that a significant proportion of the participants were not confident to assess the orthodontic treatment needs of patients (13) and managing orthodontic appliances (17). In recent years, similar findings are reported by studies on dental graduates from other countries (29). Al Gunaid et al reported consensus among orthodontic staff to include orthodontic intraoral and extraoral examinations (100 percent) in the undergraduate curriculum with 67 percent of the academics refused to allow dental students to select and bond orthodontic brackets (27). Surveys show that most dentists do not feel prepared by their predoctoral education to apply orthodontic knowledge to clinical situations where one survey reported no significant improvement in clinical diagnostic skills from year one to year four (14). Another study found that recent graduates did not recognize or refer a number of malocclusions in their general practice (30). Foster-Thomas et al. found that there is a lack of confidence in undertaking orthodontic assessments in a cohort of newly qualified dentists who graduated from universities across the UK and overseas (31)

The need for achieving consistency in undergraduate orthodontic education is evidenced by several Delphi studies to develop consensus on orthodontic teaching in undergraduate programs (5). A common message emanating from the available studies on undergraduate orthodontic education seems to emphasize a focus on assessment and diagnosis of orthodontic treatment needs of patients and a basic understanding of contemporary treatment options to facilitate patient referral (23, 27). Undergraduate dental programs may find it challenging to train their students in providing orthodontic treatments apart from dealing with orthodontic emergencies (24) . Previous studies on preparedness of dental graduates have also identified assessment and diagnosis of orthodontic treatment needs as the core skill required by new dental graduates (13, 32).

It is acknowledged that some degree of variation in orthodontic teaching and assessments at the level of individual institutions is inevitable. Nevertheless, there is merit in evaluating the alignment of LOs outlined by the regulators and dental education bodies and existing undergraduate orthodontic curricula used by dental education providers. In contrast to orthodontics, there appears to be a greater consistency in undergraduate curricula of other major clinical dental disciplines such as, restorative dentistry, periodontics, endodontics, oral surgery etc. (33-36). Relevant stakeholders need to critically evaluate the LOs which can be achieved realistically and focus on consolidating core skills rather than attempting to follow plans which are over-ambitious and unlikely to be feasible. In this regard, meaningful consultations are required amongst dental education providers, regulators, dental education associations such as, ADEE, ADA and specialist orthodontic associations such as the European and American orthodontic associations and similar organizations in individual countries. Last but not the least, it is important to reiterate that dental students are the key stakeholders and must be represented appropriately in review of undergraduate curricula (37, 38). Such consultations may help achieve clarity and a broad-based consensus regarding the LOs and competencies in undergraduate orthodontic curricula.

The main limitation of this review is that it only explored published literature on undergraduate orthodontic education and did not attempt to dissect orthodontic curricula of individual dental institutions. Although the latter exercise may have provided additional information to answer the research question in this study, given the fact that there over a thousand dental schools worldwide, it was not feasible to explore individual curricula. It is also acknowledged that some studies included in this review are more than 20 years old, and the findings may not accurately reflect the current education in respective institutions. Nevertheless, the review included studies done in Europe, USA and Asia Pacific regions and identified common messages from key stakeholders in orthodontic education including dental education regulators, education providers, students, trainees, as well as professional dental education associations.

Conclusions

Marked variations exist in the LOs, curriculum content, expected competencies and assessment methods in undergraduate orthodontic education. Dental education providers, regulators and professional bodies need to work closely to review existing undergraduate orthodontic curricula to align the LOs with teaching and assessments and achieve consistency in the design and delivery of undergraduate orthodontic education.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. Open access funding for the publication provided by XXX XXXXX XXXXXX.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable; the manuscript is a scoping review. No new data was collected for this study and ethics approval/consent to publish are not relevant.

References

- Kwo, F.; Orellana, M. The Current State of Predoctoral Orthodontic Education in the United States. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bondt, B.; Aartman, I.H.; Zentner, A. Referral patterns of Dutch general dental practitioners to orthodontic specialists. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, E.M.; English, J.D.; Johnson, C.D.; Swearingen, E.B.; Akyalcin, S. Perceptions of orthodontic case complexity among orthodontists, general practitioners, orthodontic residents, and dental students. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowpe, J.; Plasschaert, A.; Harzer, W.; Vinkka-Puhakka, H.; Walmsley, A.D. Profile and competences for the graduating European dentist – update 2009. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, V.L.S.; Van Ness, C.; Iwasaki, L.R.; Nickel, J.C.; Venugopalan, S.R.; Gadbury-Amyot, C.C. Expert consensus on Didactic Clinical Skills Development for orthodontic curricula. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouskandar, S.Y.; Al Muraikhi, L.; Hodge, T.M.; Barber, S.K. UK dental students' ability and confidence in applying the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need and determining appropriate orthodontic referral. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 27, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R. Ten-year study of strategies for teaching clinical inference in predoctoral orthodontic education. J. Dent. Educ. 1988, 52, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Lowe, A. Undergraduate and continuing education in orthodontics: a view into the 1990s. 1987, 37, 91–7.

- Harzer, W. and Oliver, R. Undergraduate curriculum in orthodontics. J. Orthod. 2002, 29, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederquist, R. Thoughts on the future of orthodontic education and practice. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1987, 92, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, S.M.; Holsgrove, G.J. New developments in assessment in orthodontics. J. Orthod. 2009, 36, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.S.; Tonni, I.; Gadbury-Amyot, C.; Van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Escudier, M. Assessment in a global context: An international perspective on dental education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 22, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Slade, A.; Kay, E.; Zahra, D.; Tredwin, C. Preparedness of undergraduate dental students in the United Kingdom: a national study. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 222, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brightman, B.B.; Hans, M.G.; Wolf, G.R.; Bernard, H. Recognition of malocclusion: An education outcomes assessment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1999, 116, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, V.S.; Van Ness, C.; Iwasaki, L.R.; Dmd, V.-L.S.F.; Dds, M.L.R.I.; Gadbury-Amyot, C.C. Expert Consensus on Growth and Development Curricula for Predoctoral and Advanced Education Orthodontic Programs. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freda, N.M. and Lipp, M. J. Test-Enhanced Learning in Competence-Based Predoctoral Orthodontics: A Four-Year Study. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 80, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, A.S.M.; Welply, A.; Cowpe, J.G.; Bullock, A.D.; Jones, R.J. The undergraduate preparation of dentists: Confidence levels of final year dental students at the School of Dentistry in Cardiff. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihm, J.J. and Seo, D. G. Does Reflective Learning with Feedback Improve Dental Students' Self-Perceived Competence in Clinical Preparedness? J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 80, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.; Popat, H.; Johnson, I.G. Dental students' experiences of treating orthodontic emergencies – a qualitative assessment of student reflections. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 20, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, M.J. A Process for Developing Assessments and Instruction in Competency-Based Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 74, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterle, L.J.; Belanger, G.K. Orthodontic competency in predoctoral education in American dental schools. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 1998, 2, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Fox, K.; Grieveson, B.; Youngson, C.C. Undergraduate training as preparation for vocational training in England: a survey of vocational dental practitioners' and their trainers' views. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 201, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, W.P. , O'Brien, K. D. and Stephens, C.D. Orthodontic teaching practice and undergraduate knowledge in British dental schools. Br. Dent. J. 2002, 192, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koole, S.; Brulle, S.V.D.; Christiaens, V.; Jacquet, W.; Cosyn, J.; De Bruyn, H. Competence profiles in undergraduate dental education: a comparison between theory and reality. BMC Oral Heal. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamidis, J.P. , Eaton, K.A., McDonald, J.P., Seeholzer, H. and Sieminska-Piekarczyk, B. A survey of undergraduate orthodontic education in 2000, 23 European countries. J. Orthod. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, U. , Mahboob, U. and Yasmin, R. Developing Faculty Consensus for Undergraduate Orthodontic Curriculum. J. Islam. Int. Med. Coll. 2017, 12, 148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gunaid, T.; Eshky, R.; Alnazzawi, A. Orthodontic curriculum in Saudi Arabia: Faculty members' perception of clinical learning outcomes. J. Orthod. Sci. 2021, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Aligning teaching for constructing learning. High. Educ. Acad. 2003, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, M.Q.; Nawabi, S.; Bhatti, U.A.; Atique, S.; AlAttas, M.H.; Abulhamael, A.M.; Zahra, D.; Ali, K. How Well Prepared Are Dental Students and New Graduates in Pakistan—A Cross-Sectional National Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDuffie, M.; Kalpins, R. Predoctoral orthodontic instruction and practice of recent graduates in Florida. J. Dent. Educ. 1985, 49, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Thomas, E.; Curtis, J.; Eckhardt, C.; Atkin, P. Welsh dental trainees’ confidence and competence in completing orthodontic assessments and referrals. J. Orthod. 2021, 48, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Slade, A.; Kay, E.J.; Zahra, D.; Chatterjee, A.; Tredwin, C. Application of Rasch analysis in the development and psychometric evaluation of dental undergraduates preparedness assessment scale. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 21, e135–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Slade, A.; Kay, E.J.; Zahra, D.; Chatterjee, A.; Tredwin, C. Application of Rasch analysis in the development and psychometric evaluation of dental undergraduates preparedness assessment scale. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 21, e135–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yudin, Z.M.; Ali, K.; Ahmad, W.M.A.W.; Ahmad, A.; Khamis, M.F.; Monteiro, N. .B.G.; Aziz, Z.A.C.A.; Saub, R.; Rosli, T.I.; Alias, A.; et al. Self-perceived preparedness of undergraduate dental students in dental public universities in Malaysia: A national study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 24, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Cockerill, J.; Zahra, D.; Qazi, H.S.; Raja, U.; Ataullah, K. Self-perceived preparedness of final year dental students in a developing country—A multi-institution study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 22, E745–E750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; McCarthy, A.; Robbins, J.; Heffernan, E.; Coombes, L. Management of impacted wisdom teeth: teaching of undergraduate students in UK dental schools. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 18, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilodeau, P.A.; Liu, X.M.; Cummings, B.-A. Partnered Educational Governance: Rethinking Student Agency in Undergraduate Medical Education. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Winter, J.; Webb, O.; Zahra, D. Decolonisation of curricula in undergraduate dental education: an exploratory study. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).