1. Introduction

The number of entities that determine the diagnosis of a disease or an abnormal condition was nearly 55,000 on the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and jumped up to 85,000 by its current revision (ICD-11) [

1]. In accordance with recent advances in medicine, life expectancy, quality of life, and overall public health across the globe have been improved. Public awareness of mental health raises gradually. However, the prevalence of mental disorders has significantly increased in recent decades worldwide [

2]. One in eight people in the world has been diagnosed with a mental disorder. One in five people who were not diagnosed with psychiatric or neurological disorders may have mental distress or mental health problems. Mental distress decreases the quality of life, causes disability, and increases mortality [

3,

4,

5]. Therefore, mental distress is an important public health burden and needs early detection and intervention.

There are several strongly validated questionnaires to assess mental distress, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [

6,

7,

8]. These instruments detect psychological symptoms of mental distress, such as depressive mood, loss of interest, fatigue, diminished energy, and anxiety. Thus, they are useful for identifying mental disorders, accordingly. However, some people deny any emotional or behavioral symptoms or do not readily express their emotional state in questionnaires. Particularly, people with alexithymia do not easily recognize their mental distress [

9]. Therefore, questionnaires that detect psychiatric symptoms using emotional words may not work for such people.

Furthermore, some people complain of mainly physical symptoms and deny mental symptoms. They are usually referred to non-psychiatric wards and end up with a diagnosis such as a condition with unknown origin, medically unexplained symptoms, or a functional somatic syndrome because their subjective symptoms cannot be explained by conventional medical examinations and tests. Common characteristics of those patients are that they recover after antidepressants and anxiolytics. This suggests that the etiopathology of mental distress is associated with chronic stress-induced dysfunctions of brain activity [

10,

11,

12]. Taken together, identifying mental distress is often complicated and there is no screening tool that particularly identifies both physical and mental symptoms of mental distress in people without any clinical diagnosis.

Since Selye postulated his stress theory based on his surprising findings that nonspecific response of the body to any demand results in adrenal hyperactivity, lymphatic atrophy, and peptic ulcer (called as a classic triad), the effects of stress on brain functions are well recognized. He distinguished acute stress from chronic stress or response to chronically applied stressors, termed as “general adaptation syndrome”, by introducing a basic concept of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis as a main mediator that influence brain activity to maintain the homeostasis in response to any challenges [

13]. At present, a diversity of stress mediators in addition to the corticotropin-releasing hormone response, including but not limited to the catecholaminergic pathway or sympathetic-adrenomedullary axis, the acetylcholinergic pathway or parasympathetic nervous system, and a recently emerging neuroimmune pathway was established [

14,

15,

16]. However, so far, a direct biomarker that determines how strongly the nervous system copes with mental distress does not exist. Thus, untangling the fundamental problem of how psychological stress can produce various mental and somatic symptoms or even diseases has not been well described yet. Therefore, we hypothesized that chronic stress might cause restless overwork of brain activity. Any psychological event that induces mental distress may be associated with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral alterations. To cope with mental distress, brain activity increases, particularly the sympathetic nervous system is activated. If not solved, it causes exhaustion or overwork of the brain activity and eventually results in mental disorders. Aging, alexithymia, alexisomia, and other predispositions make vulnerable to mental overwork and further complications leading to diseases, both mental and physical disorders. In accordance with our hypothesis, previous studies suggested that people who have recurrent mental symptoms have typical characteristics of neuroticism, including a symptom called “thinking too much” [

17,

18]. We proposed that mental distress can be characterized by subjective symptoms of excessive thinking, hypersensitivity, restless behavior, social withdrawal, and minor problems in daily life, which constitute an abnormal condition called brain overwork syndrome.

This study aimed to develop a novel tool for assessing mental distress that could be useful for both clinicians and the public. The objectives of this study were (1) to develop a novel scale that measures brain overwork symptoms; (2) to determine the psychometric properties of the novel scale in the general population.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and response distributions

This study comprised 739 participants aged 16–65 years with a mean age and standard deviation of 37.42 ± 14.7 years (

Table 1).

Among them, 524 (70.9%) were females, 593 (80.2%) were residents out of the Ulaanbaatar city, 488 (66%) were married, and 411 (55.6%) graduated high school or below, 287 (38.8%) were employed, and 500 (67.7%) had low income.

Table 2 presents the distribution of responses for each BOS item in three domains.

The response distributions were skewed toward better conditions indicating floor effects(>29%), but responses to items in excessive thinking tended to have none. A full range of responses to all items had no ceiling effects.

3.2. Reliability

Item analyses included inspecting means, standard deviations, item-to-total correlations, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω to determine internal consistency (

Table 3).

McDonald’s ω coefficients of the Mongolian version of the BOS questionnaire were as follows: overall BOS, 0.861; excessive thinking domain, 0.908; hypersensitivity domain, 0.909; and restless behavior domain, 0.889. The overall Cronbach’s α coefficient of the BOS questionnaire was 0.859. The component scores of each item were significantly correlated with the rest, which were 0.520–0.628.

ICC was calculated using a three-factor mixed-effects model with a 95% CI to determine external reliability (

Table 4).

A test-retest study was carried out on 366 participants, with an interval of 16 ± 2.3 days between two time points. Participants were aged 16 to 29, and the mean age was 21.55 ± 1.94; 194 (53%) were females. Results from ICC analyses showed that the total score of BOS was 0.75, which indicates moderate reliability. The ICC values of the domains were: excessive thinking domain, 0.73; hypersensitivity, 0.69; restless behavior domain, 0.65.

3.3. Validity

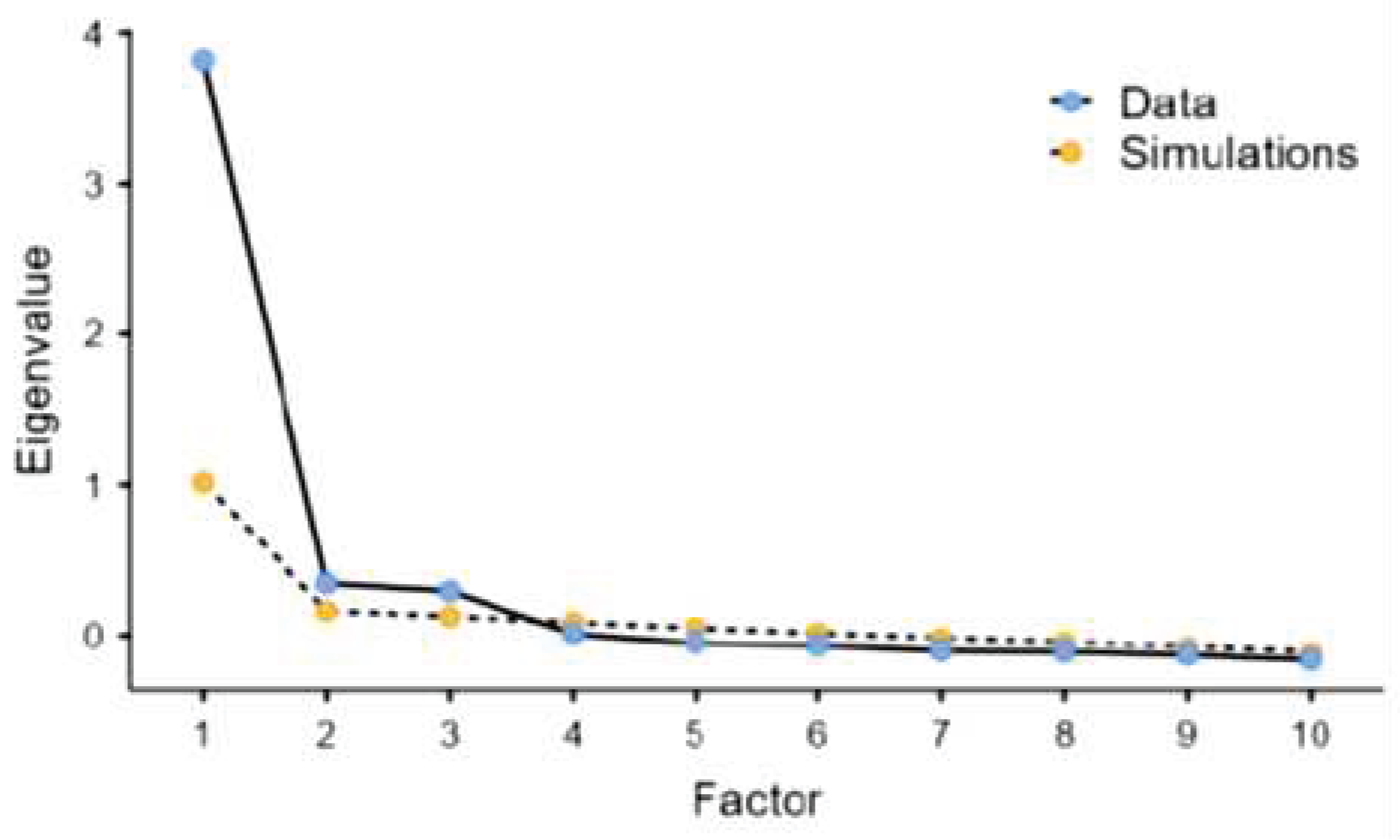

PCA using the varimax rotation method for 10 items of data identified three components with eigenvalue greater than 1, as presented by the scree plot in

Figure 1.

PCA using the varimax rotation method for 10 items of data identified three components with eigenvalue greater than 1.

The three components account for 22.9%, 20.3%, and 20% of variance, resulting in 63.2% of the total variance (

Table 5).

The KMO value was 0.908 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (P<0.001), which indicate that the data set was adequately sampled and that factor analysis of the data was appropriate.

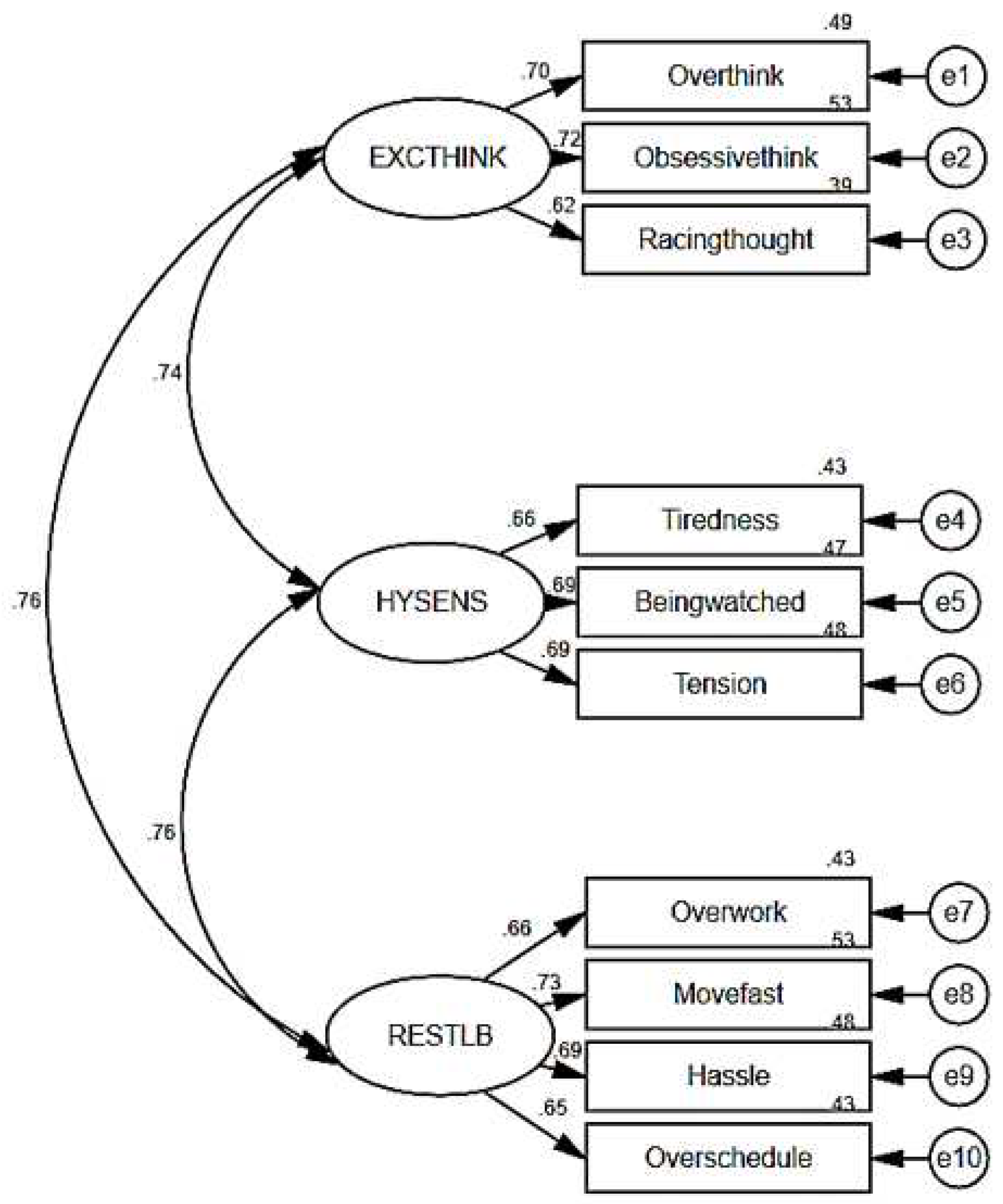

We tested the three-component model including 10 items to evaluate how well the three domains were combined to identify the underlying construct of BOS using CFA.

Figure 2 presents the factor correlations and loading.

The model had excellent fit indices (RMSEA=0.0332, CFI=0.989, TLI=984) and a test for exact fit showed a significant difference (

χ2=58.1, p=0.003). The arrows in

Figure 2 are the factor loadings, representing direct effects of the indicators on the latent BOS. The value ranged from 0.74–0.76 for the correlation coefficients between the domains and from 0.62–0.73 for the standardized regression weights. The squared multiple correlations were 0.43–0.53, whereas the measurement errors were represented from e1 to e10.

To determine convergent validity, we analyzed the correlation of each item with its corresponding domain (corrected item-total correlations) and inter-item correlations between the domains (

Table 6).

Each item was strongly correlated (≥0.4) with its corresponding domain than the other domains. There was no item correlated more strongly with another domain than with its corresponding domain. Therefore, 10 out of 10 items (100%) met the criterion for item convergence. These results supported the three-domain structure.

To determine criterion validity, we calculated the correlations of the BOS total score and domain scores with the HADS and WHOQOL-BREF total score and domain scores (

Table 7).

The BOS total score correlated with the HADS scores (Anxiety r=0.429, p<0.001; Depression r=0.288, p<0.001), which indicates that BOS identifies anxiety and depression. In contrast, the total BOS scores inversely correlated with the WHOQOL-BREF domain scores (physical health: r=-0.396, p<0.001; psychological health r=-0.277, p<0.001; Social relations r=-0.161, p<0.001; environmental health r=-0.323, p<0.001), which suggests that BOS indicates poor QOL. Each BOS domains had the similar results in the correlation to HADS and WHOQOL-BREF, an only exception was the restless behavior domain of BOS did not correlate with the social relationship domain of WHOQOL-BREF.

4. Discussion

We developed a new self-assessment scale, the BOS, which is presented as a reliable instrument for screening mental distress in the general population. The results indicate that the BOS has excellent internal consistency and moderate external reliability. Explorative PCA obtained three constructs including 10 items which was confirmed by CFA indicating good construct validity. These three dimensions, including Excessive Thinking (ET), Hypersensitivity (H), and Restless Behavior (RB), constitute the final version of the BOS (BOS-10) that have been shown to be a valid measure of the severity of mental distress in healthy subjects with no diagnosis. The results of criterion validity suggest that the BOS-10 scores estimate the severity of mental distress, particularly anxiety and depression. The BOS-10 total score and subscale scores were moderately associated with anxiety, whereas only H showed relatively strong correlation with depression. The BOS-10 also depicts a decreased quality of life. The results suggest that the BOS-10 scores indicate a decrease in physical, psychological, social and environmental health, except RB.

Out of five main dimensions we initially hypothesized in our conceptual framework, ET, H, and RB were confirmed by PCA and CFA. ET is the core symptom of the brain overwork syndrome that reflects exhaustion of brain activity due to rumination thinking. We carefully selected the items for ET based on clinical observations. Also, previous studies indicated that people with symptoms such as “thinking too much”, “too much thinking” or “too much use of brain” complain that they feel unrelated to what their world is right now within their neurotic mind indicating brain activity was affected with neuroticism and hypersensitivity [

17,

18,

24,

25]. Many studies indicated that life events, childhood maltreatment, negative feedback from parents, and family history of psychiatric diseases were related to the establishment of rumination thinking, which might be a critical pathology of depression and anxiety disorders [

26,

27]. Furthermore, it’s suggested that rumination thinking is associated with neuroticism and physical diseases, such as diabetes, arthritis, stomach/gallbladder diseases, and chronic cough, in many clinical investigations [

28,

29,

30,

31]. On the other hand, some patients tend to pay exert attention to subtle thoughts that might be associated with past psychological events or future worries. Therefore, we proposed to use excessive thinking as it covers not only rumination but also obsessive thinking.

Although hypersensitivity is associated with abnormal reactions to physical stimuli such as drug, light, or noise, we used this symptom to describe an abnormal condition when someone gets highly sensitive to psychological stimuli such as, communication problems, eyesight, or voice. Hypersensitivity might be associated with mental fatigue or brain fatigue that results in mental disorders, including chronic fatigue syndrome, depressive disorders, or suicide [

32,

33].

Restless behavior covers those symptoms associated with resistance to stress, by the general adaptation syndrome perspective. Those people who have excessive thinking tend to move fast and to be occupied with time. Such people usually think too much and often hurry up in daily works.

This new tool might be helpful to detect mental distress in individuals who are difficult to assess with conventional questionnaires. The BOS is structured of items with simple and concrete expressions that are easily recalled from diverse daily life perspectives. Therefore, it might be useful to identify patients who have alexithymia and alexisomia. Alexithymia is a personality trait characterized by difficulties in the awareness and expression of own emotions. Sifneos introduced the term and indicated alexithymia is associated with psychosomatic diseases including ulcerative colitis and asthma [

9]. In clinical practice, many patients complain of physical symptoms that cannot be clearly explained even with appropriate medical examinations, and were usually diagnosed as having medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) or functional somatic syndrome (FSS). Those patients tend to show alexithymia traits including difficulty in identifying emotions, describing feelings to others, and externally-oriented thinking. Previous literature has shown that patients with alexithymia express their mental distress as relatively strong physical symptoms [

12]. Moreover, alexisomia is characterized by personality traits of difficulties in identifying and expressing somatic sensations, meaning that patients have no words to describe their bodily states [

32,

35]. Patients with alexisomia tend to have difficulties to express their mental and somatic symptoms making them hard to understand by clinicians. Taken together, patients with alexithymia or alexisomia are thought to have difficulty to aware and describe their feelings and troubles. The BOS is composed of items made easy to understand for subjects with alexithymia and alexisomia. In clinical settings, this tool might be useful for assessing mental distress in patients with MUS and FSS.

Currently, it is not fully understood how mental distress causes psychiatric disorders. Recent in vivo studies have demonstrated that psychological stress impairs brain structures, such as the hippocampus, extended amygdala, and midbrain raphe, and leads to memory impairment, maladaptive behaviors, and vulnerability to psychosocial stress [

36,

37,

38]. For example, repeated stress exposures decrease spinogenesis and spine stability in the dorsal CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus in mice, indicating cognitive deficits [

36]. In clinical studies, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and maladjustment of the gut microbiota might be involved in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders [

32]. Taken together, this study provided a new tool that measures different dimensions of mental distress distinct from anxiety or depression and validated it in a nonclinical population.

This study has several methodological limitations and shortcomings. First, as participants were recruited from the general population of Mongolia, the three-dimensional structure of the BOS-10 is only appropriate for the particular study population. It’s recommended to use the 37-item version of BOS with 5 dimensions if tested in a different population. We had to eliminate two dimensions, including social withdrawal and minor problems in daily life symptoms, out of the 37-item version for the BOS-10. Those dimensions were supposed to detect subjects who avoid asking for help from others and try to do everything themselves not to bother others. However, these characteristics were not typical of Mongolian adults, of whom half are nomadic herders in the countryside. Moreover, nomadic people live close to nature and are relatively free from intensive digital media use, in contrast to urban dwellers. Second, although construct, convergent, and criterion validities were assessed, this study did not examine the discriminant validity. Furthermore, as a cross-sectional study, it did not provide information regarding the persistence of mental distress over time.

To improve the validity of the instrument, future studies should compare with other relevant measurement tools. To further determine the sensitivity and specificity of the instrument, the assessment need to be conducted bot in clinical and nonclinical settings using a longitudinal design. Clinical studies are needed to explain the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the brain overwork syndrome.