Submitted:

10 February 2023

Posted:

14 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Solutions

2.2. Methods and Sample Preparation

3. Results

3.1. Electrochemistry

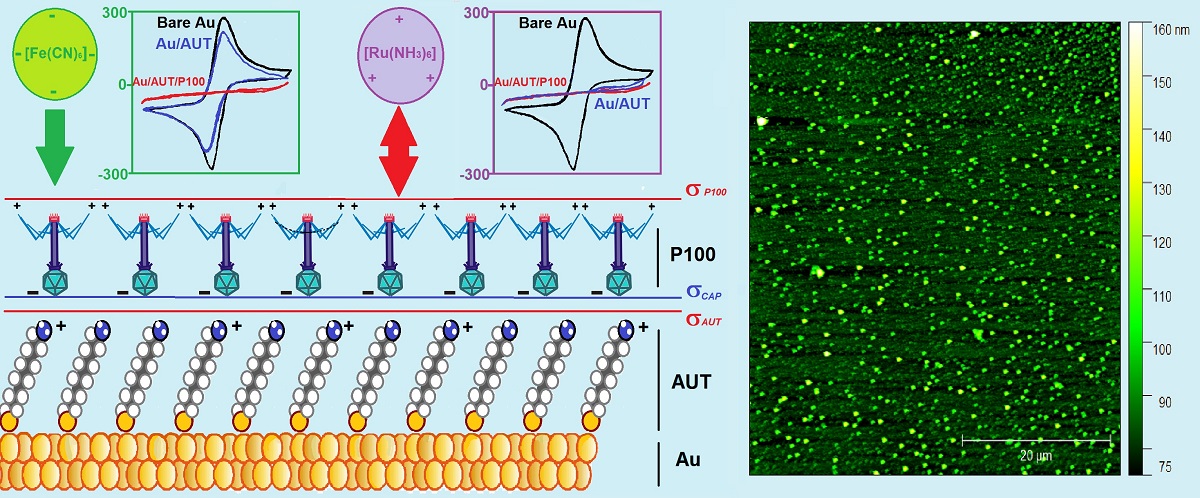

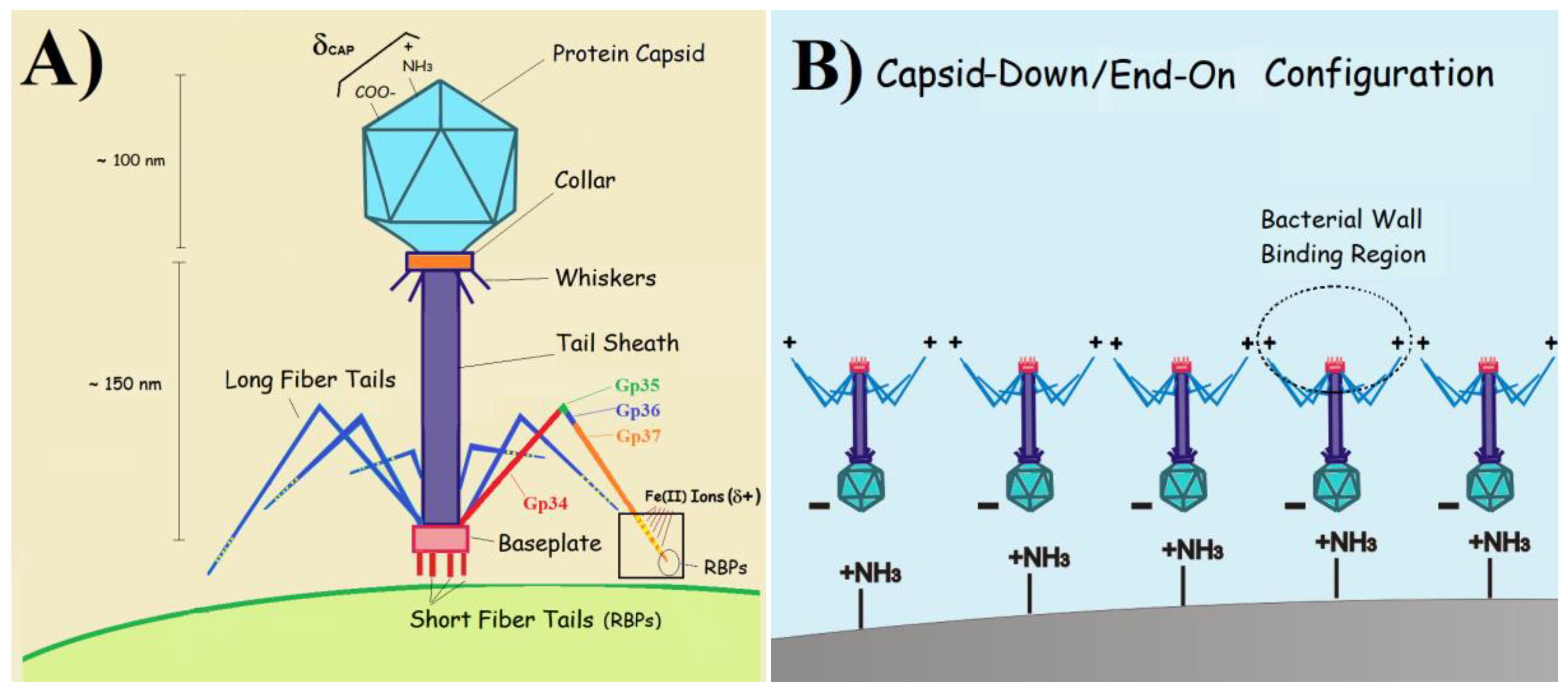

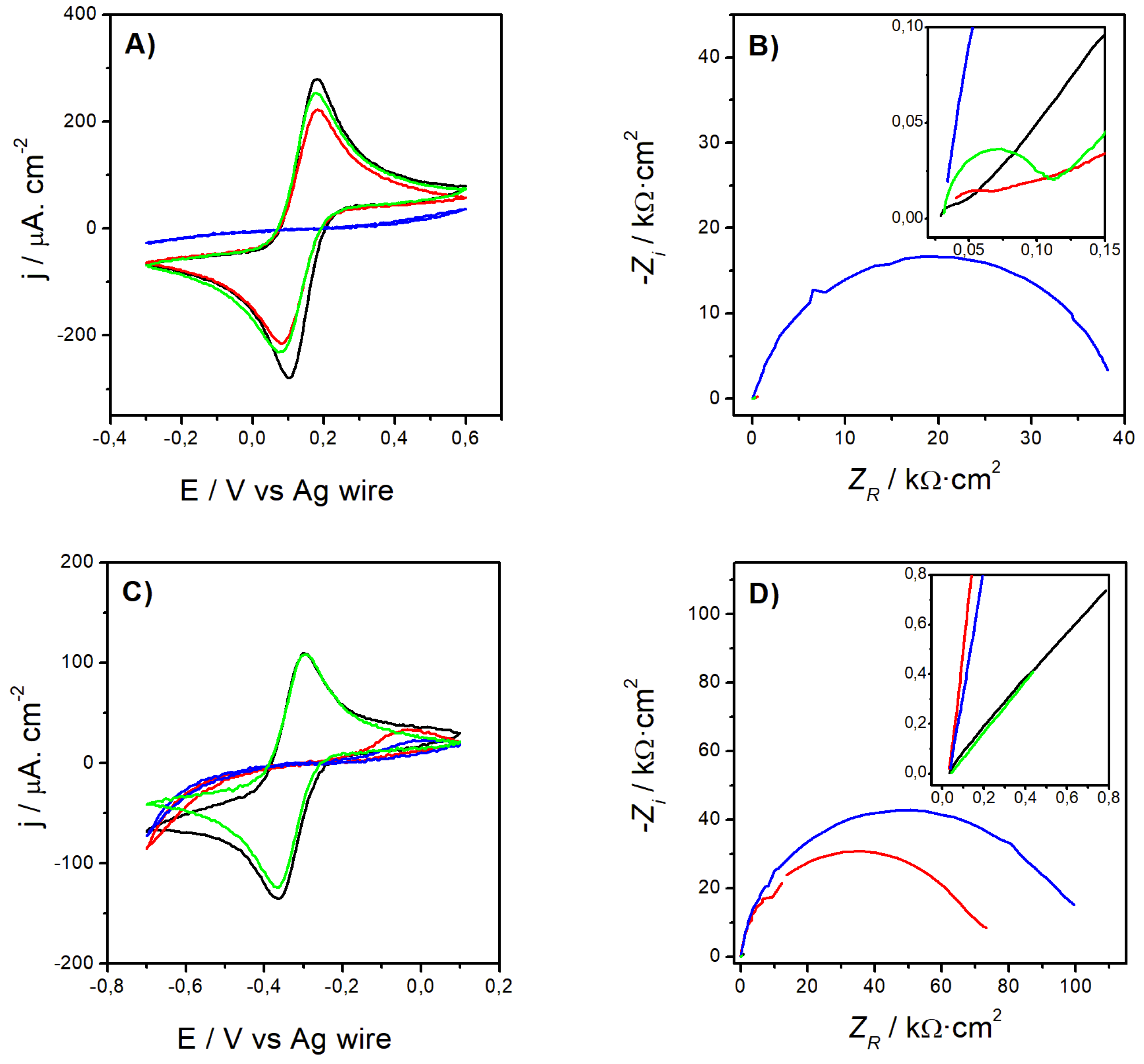

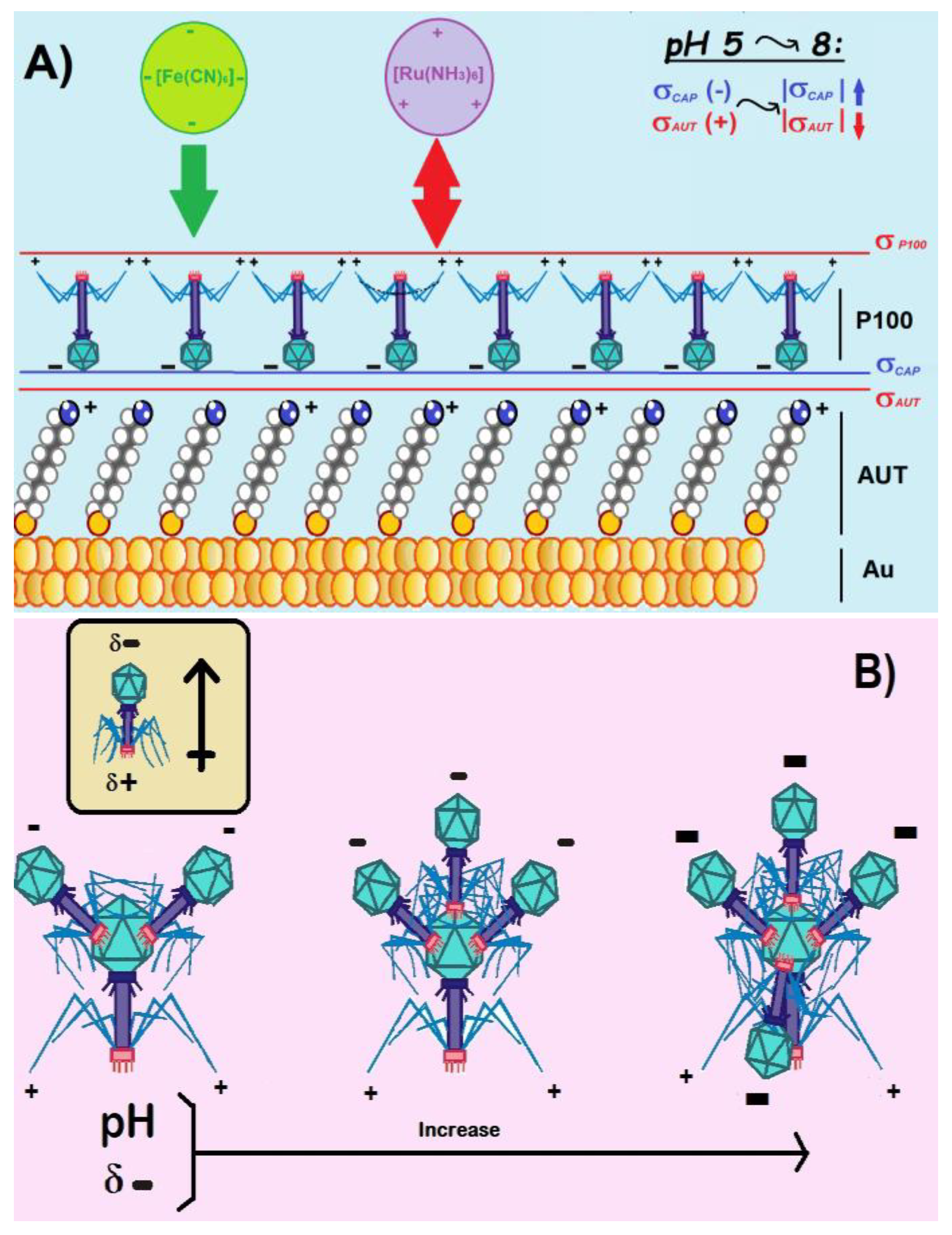

3.1.1. Electrode Characterization

- Excellent Probe Reversibility at Bare Au. As found in FE8, the CV recorded for bare Au (Figure 1C) featured the most intense Faradaic peaks (|jPA| & |jPC| both around 130 µA·cm2, Table 3) and a low ∆EP of only 64 mV (very close to the 59 mV expected for an ideal reversible pair). Its Nyquist plot (Figure 1D) also exhibited the smallest semicircle in the series and the calculated R2 was almost negligible.

- Partially Hindered Response at Au/AUT. Unlike registered in FE8, the CV recorded in RU8 exhibited very weak peaks (only the anodic can be truly discerned) and the impedance data revealed a massive growth of both the semicircle´s diameter and R2 (up to 1186 kΩ).

- Strongly Blocked Response for Au/AUT/P100. The further deposition of P100 phages led

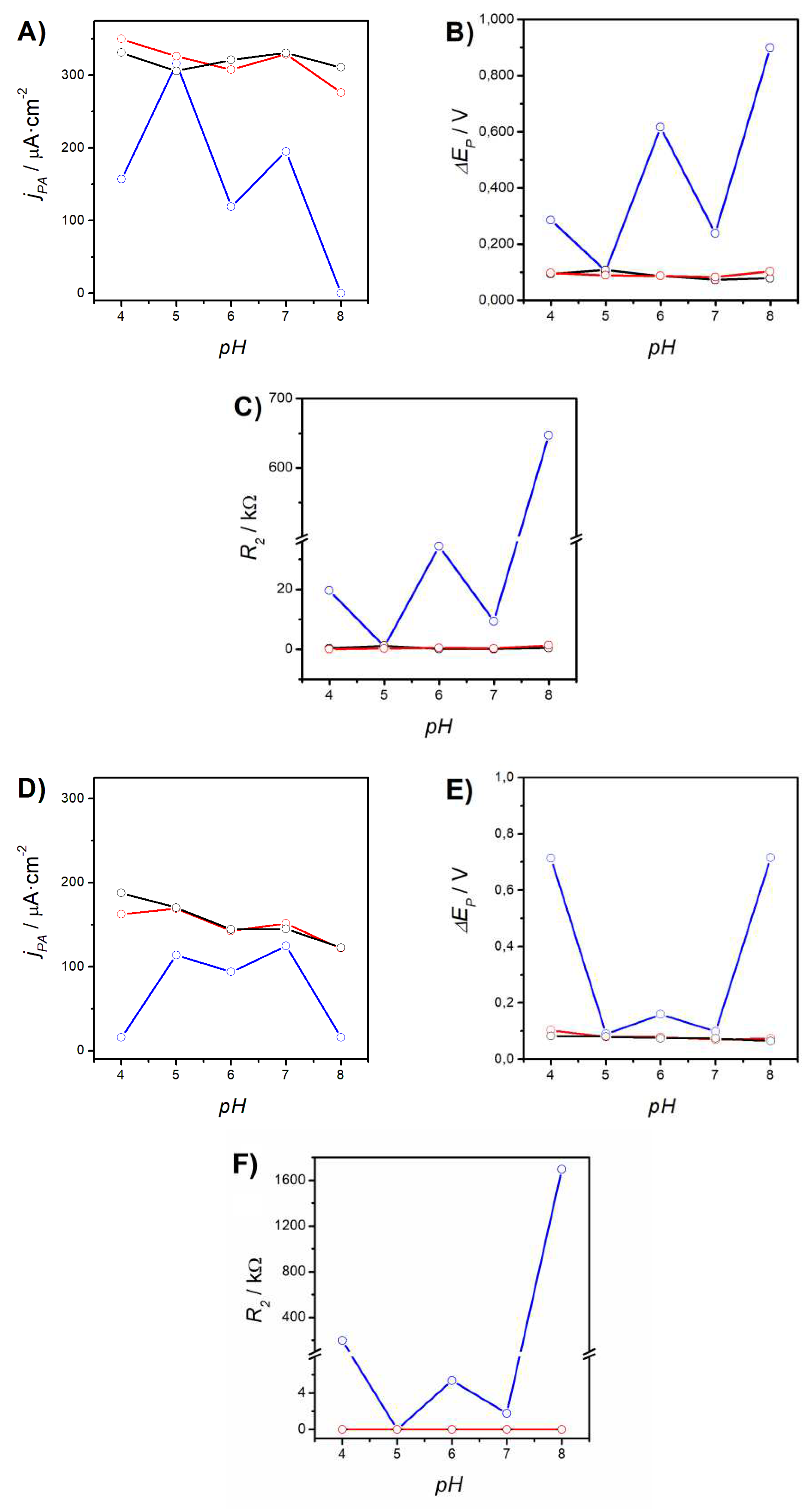

3.1.2. Role of the Electrolyte pH

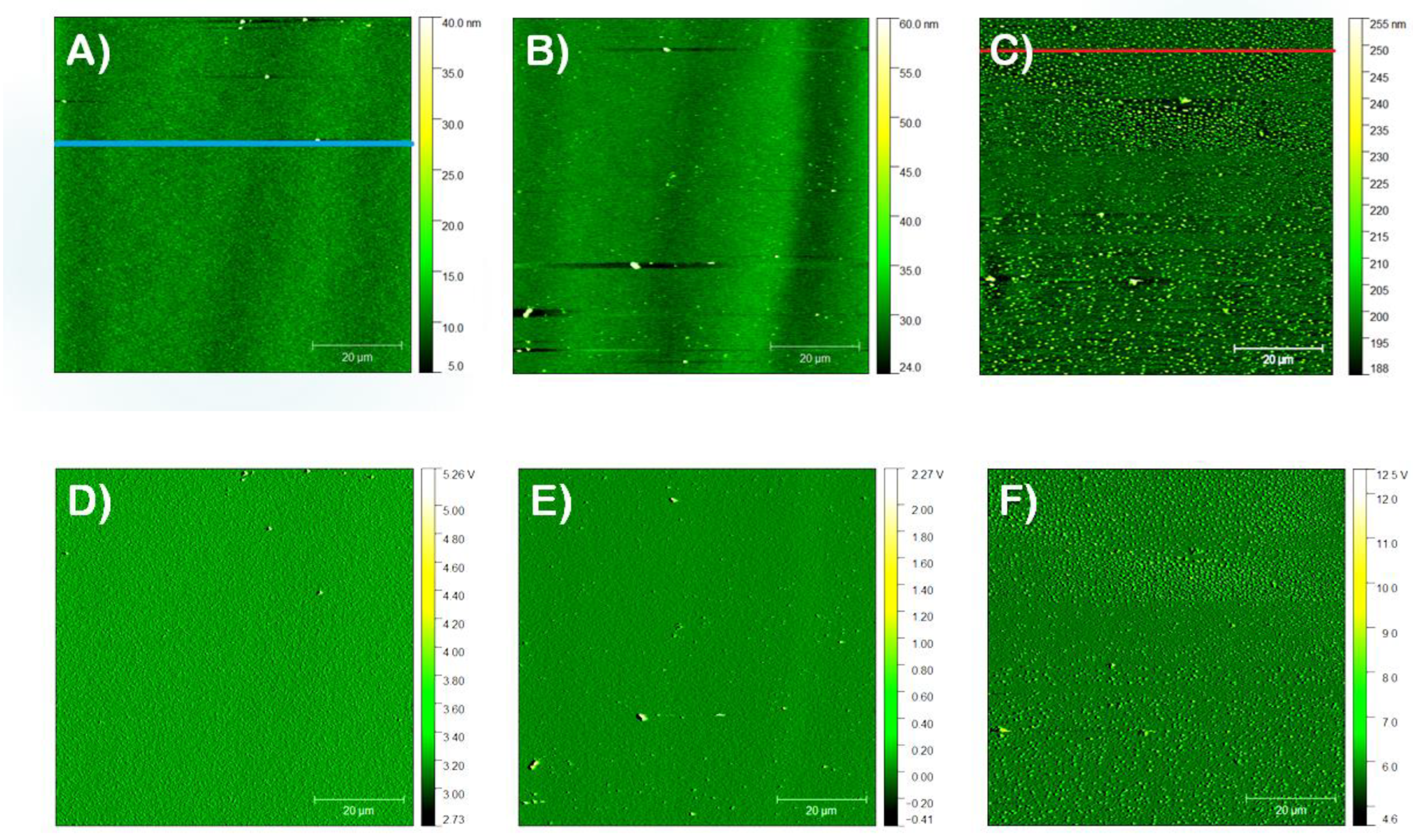

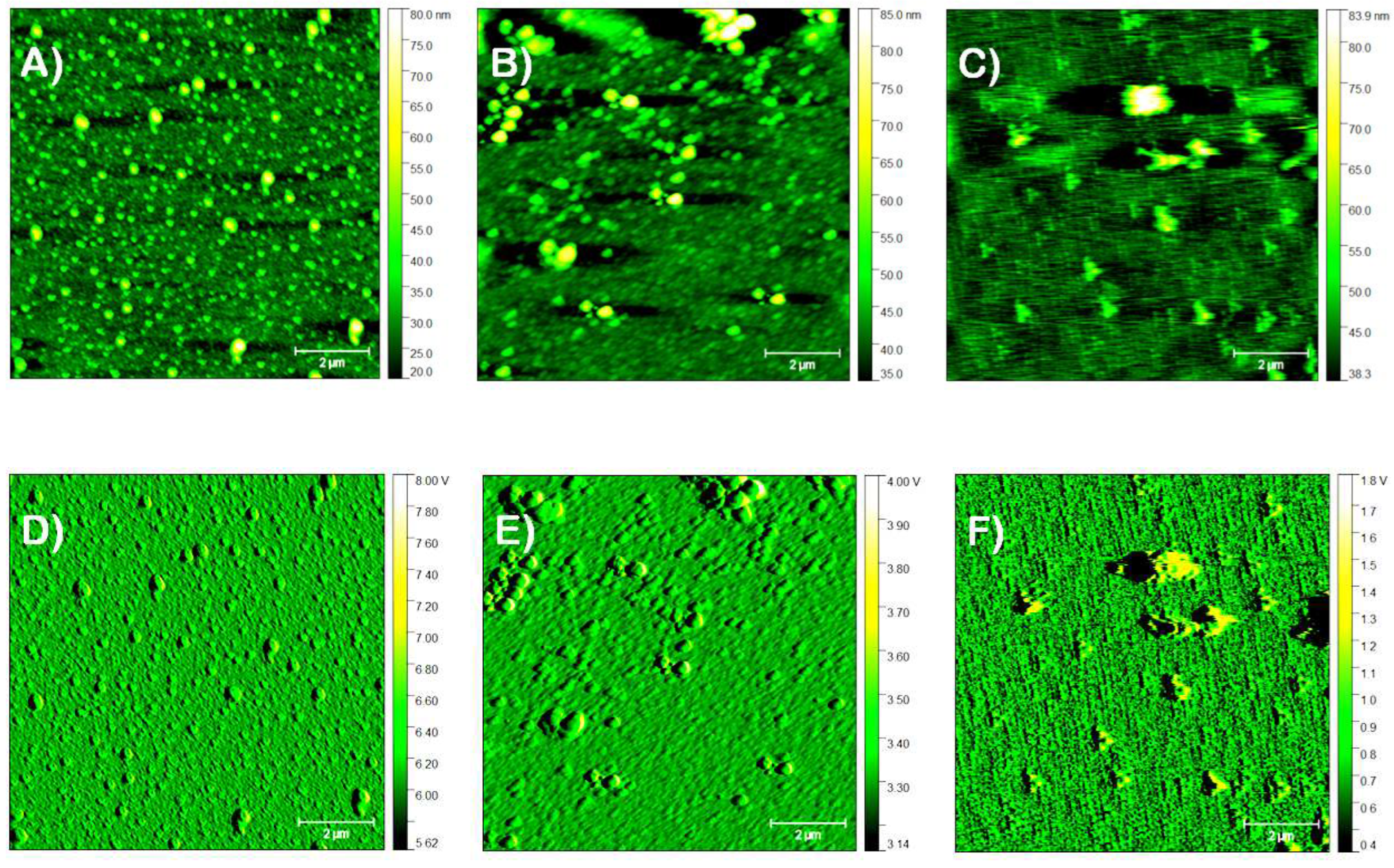

3.2. AFM Studies

3.2.1. Film Morphology

3.2.2. Precursor Dispersion pH

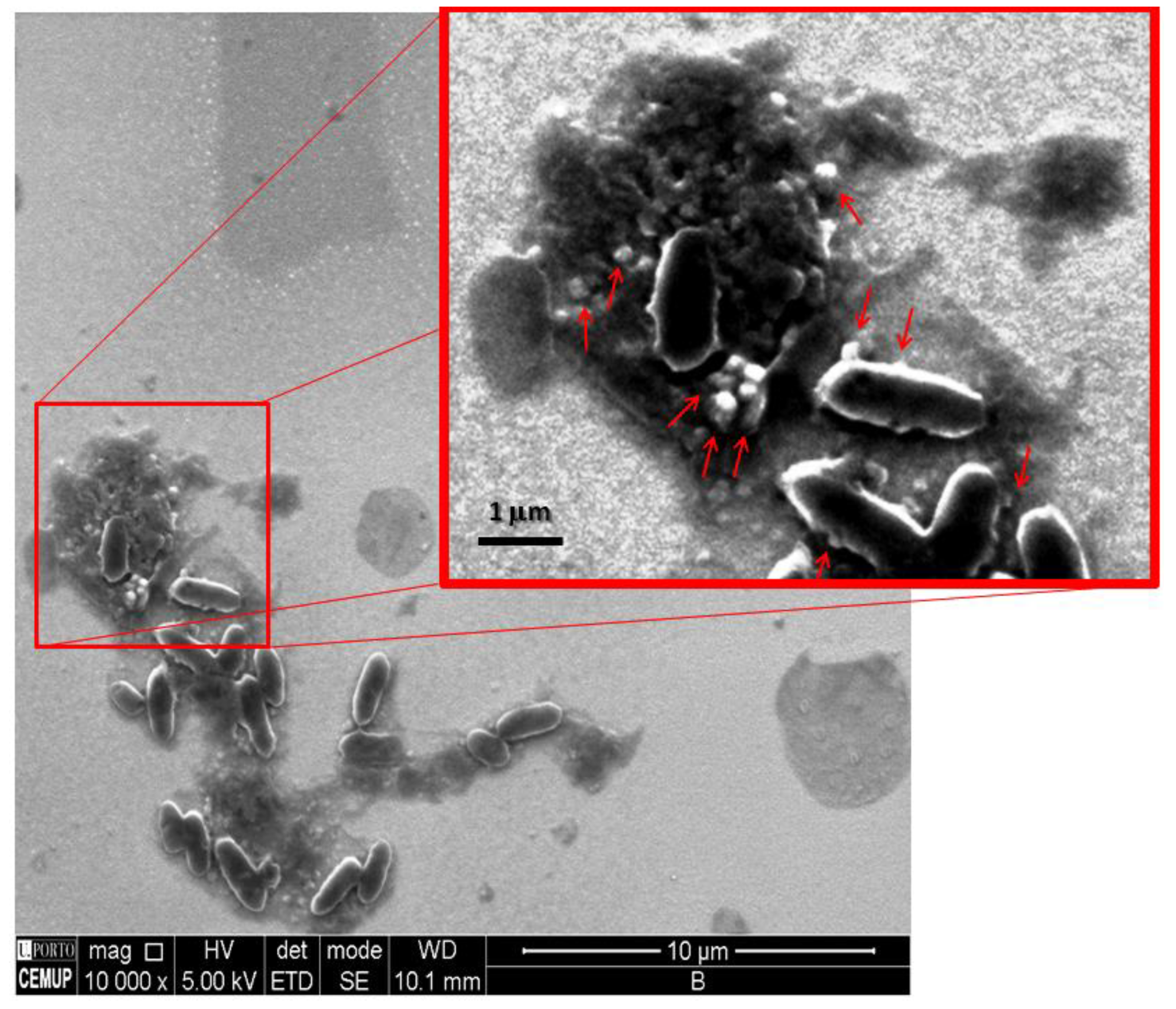

3.3. FE-SEM Studies

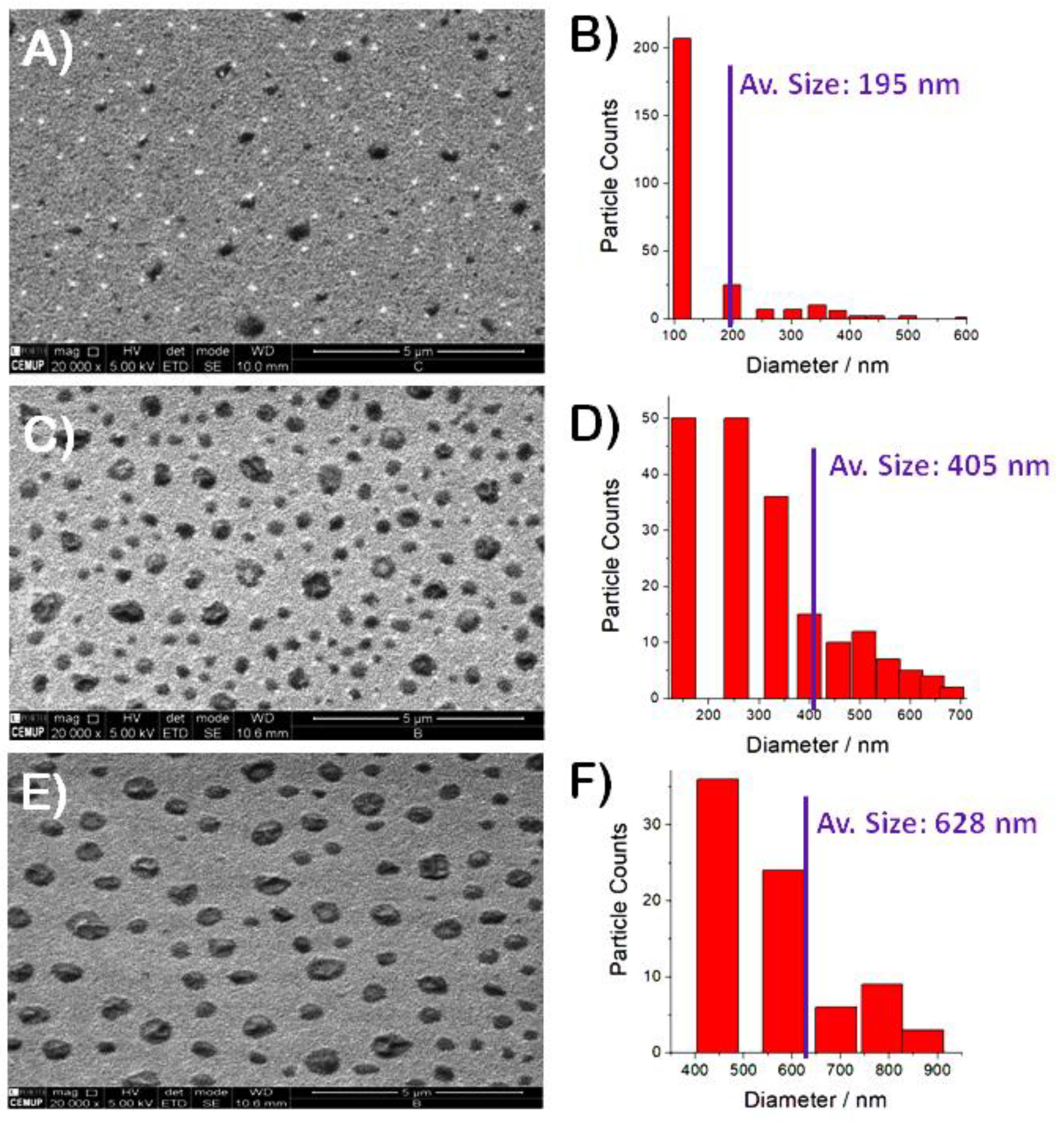

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klumpp, J.; Dorscht, J.; Lurz, R.; Bielmann, R.; Wieland, M.; Zimmer, M.; Calendar, R.; Loessner, M.J. The Terminally Redundant, Nonpermuted Genome of Listeria Bacteriophage A511: a Model for the SPO1-Like Myoviruses of Gram-Positive Bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5753–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barylski, J.; Kropinski, A.M.; Alikhan, N.F.; Adriaenssens, E.M. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Herelleviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 362–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Wu, Y. Colorimetric Sensor Array Based on Gold Nanoparticles with Diverse Surface Charges for Microorganisms Identification. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 10639–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-McCarthy, L.R; Mijalis, A.J.; Filsinger, G.T.; de Puig, H.; Donghia, N.M.; Schaus, T.E.; Rasmusen, R.A.; Ferreira, R.; Lunshof, J.E.; Chao, G.; Ter-Ovanesyan, D.; Dodd, O.; Kuru, E.; Sesay, A.M.; Rainbow, J.; Pawlowski, A.C.; Wannier, T.M.; Yin, P.; Collins, J.J.; Ingber, D.E.; Church, G.M.; Tam, J. M. Anomalous COVID-19 Tests Hinder Researchers. Science 2021, 371, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiaux, A.D.; Pinger, C.W.; Hayter, E.A.; Bunn, M.E.; Martin, R.S.; Spence, D.M. PolyJet 3D-Printed Enclosed Microfluidic Channels without Photocurable Supports. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 6910–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.F.; Almeida, C.M.; Magalhães, J.M.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Freire, C.; Delerue-Matos, C. Development of a disposable paper-based potentiometric immunosensor for real-time detection of a foodborne pathogen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y. Functional Nucleic Acid Based Biosensor for Microorganism Detection. In Functional Nucleic Acid Based Biosensors for Food Safety Detection. Springer: Singapore, China, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Malekzad, H.; Jouyban, A.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Shadjou, N.; de la Guardia, M. Ensuring Food Safety Using Aptamer Based Assays: Electroanalytical Approach. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2017, 94, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonczyk, E.; Klak, M.; Miedzybrodzki, R.; Gorski, A. (2011). The Influence of External Factors on Bacteriophages-Review. Folia Microbiol. 2011, 56, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Arya, S.K.; Glass, N.; Hanifi-Moghaddam, P.; Naidoo, R.; Szymanski, C.M.; Tanha, J.; Evoy, S. Bacteriophage Tailspike Proteins as Molecular Probes for Sensitive and Selective Bacterial Detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, M.; Minikh, O.; Brovko, L.Y.; Evoy, S.; Griffiths, M.W. Oriented Immobilization of Bacteriophages for Biosensor Applications. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.A.; Wang, Q. Adaptations of Nanoscale Viruses and other Protein Cages for Medical Applications. Nanomedicine 2006, 2, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.A; Niu, Z.; Wang, Q. Viruses and Virus-like Protein Assemblies-Chemically Programmable Nanoscale Building Blocks. Nano. Res. 2009, 2, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.K.; Singh, A.; Naidoo, R.; Wu, P.; McDermott, M.T.; Evoy, S. Chemically Immobilized T4-bacteriophage for Specific Escherichia coli Detection Using Surface Plasmon Resonance. Anal. The 2011, 136, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, H.; Gurczynski, S.; Jackson, M.P.; Mao, G. Immobilization and Molecular Interactions between Bacteriophage and Lipopolysaccharide Bilayers. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12095–12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Poshtiban, S.; Evoy, S. Recent Advances in Bacteriophage Based Biosensors for Food-Borne Pathogen Detection. Sensors 2013, 13, 1763–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanduri, V.; Sorokulova, I.B.; Samoylov, A.M.; Simonian, A.L.; Petrenko, V.A.; Vodyanoy, V. Phage as a Molecular Recognition Element in Biosensors Immobilized by Physical Adsorption. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntupalli, R.; Sorokulova, I.; Long, R.; Olsen, E.; Neely, W.; Vodyanoy, V. Phage Langmuir Monolayers and Langmuir–Blodgett Films. Colloids Surf. B 2011, 82, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, N.; Sacher, E.; Mandeville, R.; Meunier, M. Strategies for the Immobilization of Bacteriophages on Gold Surfaces Monitored by Surface Plasmon Resonance and Surface Morphology. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 6686–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Sela, D.A.; Nugen, S.R. Development of a Novel Bacteriophage based Biomagnetic Separation Method as an Aid for Sensitive Detection of Viable Escherichia coli. Anal. The 2016, 141, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Song, H.; Kim, C.; Moon, J.S.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.W.; Oh, J.W. Biomimetic Self-templating Optical Structures Fabricated by Genetically Engineered M13 Bacteriophage. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwer, P. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis of Bacteriophages and Related Particles. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1987, 418, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anany, H.; Chen, W.; Pelton, R.; Griffiths, M.W. Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Meat by Using Phages Immobilized on Modified Cellulose Membranes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6379–6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nap, R.; Božič, A.; Szleifer, I.; Podgornik, R. The Role of Solution Conditions in the Bacteriophage PP7 Capsid Charge Regulation. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lone, A.; Anany, H.; Hakeem, M.; Aguis, L.; Avdjian, A.C.; Bouget, M.; Atashi, A.; Brovko, L.; Rochefort, D.; Griffiths, M.W. Development of Prototypes of Bioactive Packaging Materials Based on Immobilized Bacteriophages for Control of Growth of Bacterial Pathogens in Foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 217, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonasek, E.; Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y.L.; Nitin, N. Bacteriophages Immobilized on Electrospun Cellulose Microfibers by Non-specific Adsorption, Protein–Ligand Binding, and Electrostatic Interactions. Cellulose 2017, 24, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Ullah, M.W.; Yang, Q.; Aziz, A.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S. High-Density Phage Particles Immobilization in Surface-Modified Bacterial Cellulose for Ultra-Sensitive and Selective Electrochemical Detection of Staphylococcus Aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 157, 112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, M.; Mine, K.; Tomonari, H.; Uchiyama, J.; Matuzaki, S.; Niko, Y.; Hadano, S.; Watanabe, S. Dark-Field Microscopic Detection of Bacteria using Bacteriophage-Immobilized SiO2@AuNP Core–Shell Nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 12352–12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, U.; Matuła, K.; Leśniewski, A.; Kwaśnicka, K.; Łoś, J.; Łoś, M.; Paczesny, J.; Hołyst, R. Ordering of Bacteriophages in the Electric Field: Application for Bacteria Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 224, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiña, J. M.; Souza, H. K.; Borges, J.; Martins, A.; Gonçalves, M. P.; Silva, F. (2010). Studies on the Interactions between Bovine β-lactoglobulin and Chitosan at the Solid–Liquid Interface. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 8779–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.; Campiña, J.M.; Silva, A.F. Chitosan Biopolymer–F(ab′)2 Immunoconjugate Films for Enhanced Antigen Recognition. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PhageGuard Listex GRAS approved for 10 years! – PhageGuard.com. Available online: https://phageguard.com/phageguard-listex-gras-approved-for-10-years/ (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Plaque Assay: A Method To Determine Viral Titer As Plaque Forming Units (PFU) – JoVE Science Education Database. Available online: https://www.jove.com/v/10514/plaque-assay-a-method-to-determine-viral-titer-as-plaque-forming-units-(pfu) (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Kropinski, A.M.; Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. (2009). Enumeration of Bacteriophages by Double Agar Overlay Plaque Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campiña, J.M.; Martins, A.; Silva, F. Selective Permeation of a Liquidlike Self-Assembled Monolayer of 11-Amino-1-undecanethiol on Polycrystalline Gold by Highly Charged Electroactive Probes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 5351–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Drab, M.; Mąkosa, M.; Zembala, M.; Barbasz, J.; Dąbrowska, K.; Boratyński, J. Aggregation/Dispersion Transitions of T4 Phage Triggered by Environmental Ion Availability. J. Nanobiotechnology 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.L.; Ralston, E.J.; Eiserling, F.A. Bacteriophage SPO1 Structure and Morphogenesis. II. Head Structure and DNA Size. J. Virol. 1983, 46, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López de Dicastillo, C.; Settier-Ramírez, L.; Gavara, R.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; López Carballo, G. Development of Biodegradable Films Loaded with Phages with Antilisterial Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fister, S., Mester, P., Sommer, J., Witte, A. K., Kalb, R., Wagner, M., Rossmanith, P. Virucidal Influence of Ionic Liquids on Phages P100 and MS2. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, R. S., Guntupalli, R., Hu, J., Kim, D. J., Petrenko, V. A., Barbaree, J. M., Chin, B. A. Phage Immobilized Magnetoelastic Sensor for the Detection of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 71(1), 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. Z. Fokine, A., Mahalingam, M., Zhang, Z., Garcia-Doval, C., van Raaij, M. J., Rossmann, M. G., Rao, V. B. Molecular Anatomy of the Receptor Binding Module of a Bacteriophage Long Tail Fiber. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartual, S. G., Otero, J. M., Garcia-Doval, C., Llamas-Saiz, A. L., Kahn, R., Fox, G. C., van Raaij, M. J. Structure of the Bacteriophage T4 Long Tail Fiber Receptor-Binding Tip. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107(47), 20287–20292. [CrossRef]

- Randles, J. E. B. Kinetics of Rapid Electrode Reactions. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1947, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrolyte | Solvent | pH | Redox Probe | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE4 | AB 0.05 M | 4 | [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- | 2 mM |

| RU4 | AB 0.05 M | 4 | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ | 2 mM |

| FE5 | AB 0.05 M | 5 | [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- | 2 mM |

| RU5 | AB 0.05 M | 5 | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ | 2 mM |

| FE6 | PBS 0.05 M | 6 | [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- | 2 mM |

| RU6 | PBS 0.05 M | 6 | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ | 2 mM |

| FE7 | PBS 0.05 M | 7 | [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- | 2 mM |

| RU7 | PBS 0.05 M | 7 | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ | 2 mM |

| FE8 | PBS 0.05 M | 8 | [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- | 2 mM |

| RU8 | PBS 0.05 M | 8 | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ | 2 mM |

| Electrode | jPA / µA·cm2 | EPA / mV | jPC / uA·cm2 | EPC / mV | ∆EP / mV | R2 / kΩ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | 311 | 179 | -315 | 101 | 79 | 0.460 |

| Au/AUT | 246 | 179 | -241 | 81 | 99 | 0.857 |

| Au/AUT/P100 | - | - | - | - | >900 | 647.0 |

| Au/P100 | 276 | 179 | -255 | 76 | 104 | 1.324 |

| Electrode | jPA / µA·cm2 | EPA / mV | jPC / uA·cm2 | EPC / mV | ∆EP / mV | R2 / kΩ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | 123 | -295 | -135 | -365 | 64 | ≈0 |

| Au/AUT | 20 | -36 | - | - | >664 | 1186 |

| Au/AUT/P100 | 16 | 15 | - | - | >715 | 1697 |

| Au/P100 | 122 | -295 | -128 | -370 | 74 | ≈0 |

| Slide | RMS / nm | HAV / nm | HMP / nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare Au | 1.56 | 11 | 101 |

| Au/AUT/P100 | 8.52 | 145 | 282 |

| Au/P100 | 2.26 | 30 | 125 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).