Discussion

As mentioned in the introduction, there are many elements of analysis and conceptualisation of the Aymara. This analysis, which focuses on the genesis, concept and development of this ethnic group within the territorial and spatial space of the Andean south of Peru, must be exposed as essential elements for a true understanding of what the Aymara ethnic component is, far from the history that distorts the historical complexity of this. However, in order to carry out this analysis, elements such as documentary sources, chronicles and linguistic distribution will be used. These will have to be contrasted with archaeological evidence in order to support or refute what is mentioned in the documentary records.

In this regard, it must be pointed out that much of the information gathered through primary documentary sources presents interpretations that are not very accurate, given that their source of information is born of oral components that may have been modified with the passage of time over two centuries, a period in which the Wari kingdom disintegrated until its penetration into Inca society in the second period after the "mythic Incas" (Cerrón Palomino, Rodolfo 2004, 13).

The historical analysis of Aymara as a linguistic component is fundamental to delimit its spatial origin, as well as, from the archaeological aspect, to evidence its presence and conceptual influence in surrounding populations. In this way, we can clarify whether aymara, as a culture, had a real iconographic and semiological representativeness, the same that can be taken as its own cultural component or whether it was only a mere linguistic process of initially commercial and later social exchange, as mentioned by (Cerrón Palomino, Rodolfo et Kaulicke, Peter 2010, 10), (Renfrew, Colin. 2010, 25), (Heggarty, P., & Beresford-Jones, D. 2010, 33,44.), (Burguer; Richard, 2014, 139), et al. Notwithstanding this element, it should be noted that all archaeologists and studies agree on a pattern of germination of the protoaimara—influenced by the Jaqu Aru and Cauqui —, in the Central Andean region of Peru and not in the southern Andes.

However, until now, in archaeo-linguistics it has not been possible to effectively determine which linguistic component is the predecessor, that is, if it was first Aimara or Quechua that was composed of Jaqu Aru elements, even though they share these -CFR. Aimara and Quechua-, temporal elements correlative to the great social displacements subsequent to the state implosions of the formative kingdoms of the Peruvian central Andean region. In this sense, it is difficult to establish the temporal origin and unique component of the Aimara in this process.

During the pre-Inca period, the Aimara language was confined to the Central Andes (Quesada Castillo, Félix) 2012, 79-81), (R. Cerrón Palomino 2000, 135-136), (Parsons, J., Hastings, C., & M., R. 1997, 319) and (Burguer; Richard 2014, 134). The development process of integration of Jaqu Aru components in the Peruvian Central Andes resulted in the conformation of linguistic processes close to what we know today as: Aimara.

The transfer of populations due to the development of social mobility for commercial and silvopastoral purposes in this region caused these Protoquechua and Proto-Aimara populations to create a linguistic form that allowed an easy and accessible exchange of livestock and agricultural products for the subsistence (Quesada Castillo, Félix. 2012, 81) and (Parsons, J., Hastings, C., and M., R. 1997, 319) during the Early and Middle Horizon.

Culturally, the Aymara language and ethnic group derives from the settlements of northern central Peru.

This issue concerns the medullary data on the expansive process of Aymara as a phonetic component towards the Central Andes and the coastal region of northern Peru during the Chavín period towards the Early Formative. (Burguer; Richard 2014, 141). However, in this linguistic development, a phonological and semantic conjunction of aymara with protoquechua can be evidenced, in such a way that this initial integration does not evidence a preponderance of what is purely Aymara. Therefore, this semantic drift makes it difficult to define in a tangential and open way what is and what is not Aymara. However, both phonetic and linguistic components would have roots in Jaqu Aru and Cauqui as a linguistic-cultural base.

From a semiotic perspective, the pictorial and iconographic representation, as the basis of the cultural and linguistic expression of these territories -Cfr. Central Andes-, shows that the patterns of the populations of the Chillón and Cañete valley, as well as the north central and south central Andean from Peru, have a mixture of cultural and iconographic expressions consistent with the Wari expansion process, therefore, an expansion of the Aymara linguistic base; based on the “Global Culturization” (Jennings, Justin. 2012, 38).

In addition, Cerrón Palomino (2010) shows that this Jaqu Aru component would have been concentrated in a proto-Quechua in the headwaters of the Chillón basin, but that, however, these dialects would have shared bases with Aymara, thus giving a predominance towards the valleys to the south of this a predominance of the Aru derivation towards Aymara, but without leaving the consubstantial base of quechua. Both elements during the Formative period show that aymara was not limited to southern Andean Peru during this period; rather, it was a later cultural imposition.

At this point, it comes into debate based on archaeological evidence and theoretical proposals; since, according to the same description of (Torero 1972), the Puquina and Uru quilla, which were languages of the Qullasuyu, expanded towards the limits of the cultural influence of Wari and the semantic cultural tributary of the Jaqu Aru, being found in the slopes of Ica, Nazca the presence of these linguistic and cultural elements. These linguistic components were those found by the Spanish conquerors on their journey to Cuzco (Mariño de Lobera 1865 (1552), 27). In this sense, from an archaeological perspective, there is no evidence of an Aymara component as such. In this phase of development between cultural elements and semiological and semantic patterns, the pictographic correspondence between the Aymara element and the Quechua or Tiawanaku element cannot be defined.

The geometric pictorial patterns of trapezoids and quadrangles do not allow making such differentiation, since such cultural elements were appreciated in textile and pottery components much older than the Wari process; besides, they are predominant in the Qullasuyan region as well as in the Chinchaysuyo region, reason why these elements would not be patronymic components of the Aymara, but rather a cultural appropriation of them.

From the analysis of the pictographic and iconographic patterns, we can infer that these cultural elements have a cultural influence of Moche and Chimú; elements that are consistent with the evaluation of textiles and iconography associated with these, which also contain iconographic elements developed by the Aymara speakers (Surette, Flannery K. 2015, 74) and (Quequezana Lucano, Gladys Cecilia; Yépez Álvarez, Willy J. y López Hurtado, Marko Alfredo. 2012, 121).

These geometric patterns represented in the Wari elements are consistent with the cultural elements of the Moche and Chimú cultures, which were adopted by cultural developments throughout the western Andes of the Central Andean region of Peru. This pattern, evidence that the iconography of the Chinchas—Aimaras, had direct influence from predecessor cultural developments, such as Chavín, Moche and Virú; these patterns, interpreted by the “Aymara nation” as their own were in reality, cultural integrations of other social components (Carlson 2019, 236).

This interculturalization on the Central Andes, evidences that, many of the elements of pictographic representation of social components after the Chavín, Chimú, Moche processes and all those that coexisted between the Early Horizon and the Middle Horizon (900 BC—1200 AD), making that, such integrations (cultural appropriations) formed the Wari composition. However, all these elements do not constitute a foundational and agglutinating element of the “aymara”. In addition, (Pérez Calderón, Zacarías Ismael 2016), adds that, during the expansion of the coastal populations of the Peruvian Andean Center, they were settled towards the region of the Central South Andean Andes of Peru.

This immigration of the Wari, evidenced a new integration of cultural components of the protoquechua and the Jaqu Aru of the coastal populations of Nazca, Ica and Lima (Pérez Calderón, Zacarías Ismael 2016, 40).

Likewise, the sequential composition at the architectural level of the Wari during the Middle Horizon evidences that, many nuclei of commercial confluence, developed architectural, commercial and ceremonial sites from Lambayeque to the southern end of Arequipa, as well as towards the Andean foothills of Ayacucho and Apurimac. This study demonstrates that, although these elements have Wari influences, they maintain their Yungas-Puquina (Tiawanakota) cultural components (Sullca Huarcaya 2022, 18-19).

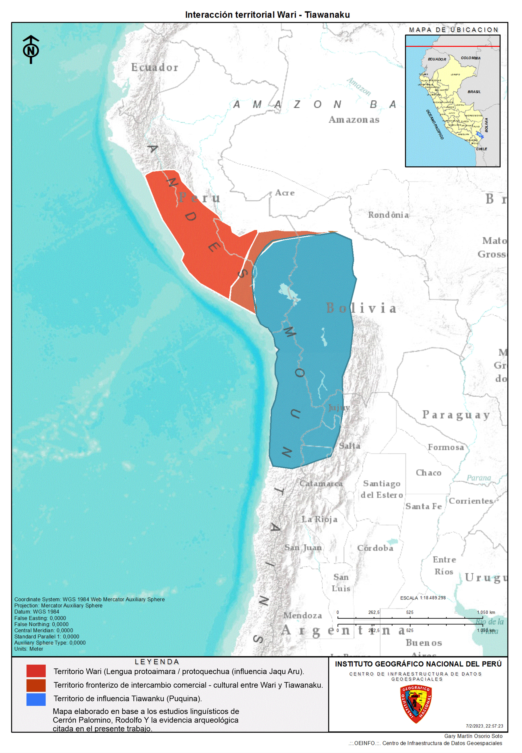

Figure 1.

Early Intermediate Period. Initial sites of the major languages of ancient Peru (drawing: Nicanor Domínguez Faura, October 2011). Source: Cerrón Palomino R. Contacts and linguistic displacements in the Central-Southern Andes: Puquina, Aimara and Quechua, 2010, p. 259.

Figure 1.

Early Intermediate Period. Initial sites of the major languages of ancient Peru (drawing: Nicanor Domínguez Faura, October 2011). Source: Cerrón Palomino R. Contacts and linguistic displacements in the Central-Southern Andes: Puquina, Aimara and Quechua, 2010, p. 259.

Evidently, these processes of cultural influence in the phonetic, pictorial and architectural components were promoted by commercial exchange, without this necessarily representing a pattern of belonging to that social group; rather, this would correspond to models of functionality that were occurring throughout the territory of the Chinchanysuyo and part of the Contisuyo. Given these cultural elements, it is predictably difficult to identify the “original” component of the Aymara, especially during the pre-Inca period of the Middle Horizon.

Such articulation has led to debate in academic circles that certain onomastics components of Hanan Cuzco were attributed to Aymara, but, however, as researchers point out, this could have originated as part of the semantic and phonetic integration between Jaqu Aru and the initiators of Aymara and the Quechua language, so that it cannot be determined with certainty whether the presence of these onomastics components north of Cuzco correspond directly to an Aymara component or to an interaction of Jaqu Aru.

The work of (Glowacki, Mary et McEwan, Gordon. 2001) confirms the occupation of a component associated with the Wari around Pikallacta and Huaro. This site -according to the words of the researchers- was an adaptation of the Late Intermediate period (Late Horizon), but that, nevertheless, archaeological evidence from the area indicates that the local inhabitants maintained elements of the local pictographs; therefore, the ceramic pictographic expression in the pre-Inca Cuzco period laid the groundwork for a cultural association (influence) (Glowacki, Mary et McEwan, Gordon. 2001, 36-39).

However, it cannot be determined whether this influence is the product of an occupation process or of an economic-productive interrelationship, which gave way to a cultural influence. Similarly, to what (Glowacki, Mary et McEwan, Gordon. 2001). The research conducted by archaeologists (Bélisle, Véronique et Quispe-Bustamante, Hubert. 2017) would add another component, which is that, evidently a Wari behavior can be observed in ceramic pattern in the Cuzco regions of Hurcos, Pikallacta, Chanapata, Muyu Urqu, Ak’awillay and Minaspata influenced by a Wari cultural element, but that, nevertheless, such patterns maintain a primordial component, which can be identified as Quechua or protoquechua of the Early Intermediate Jaqu Aru period

i. Therefore, this component of overlapping cultural variants demonstrates a broad and productive exchange in the border area between Ayacucho and Cuzco.

To complement the archaeological work previously developed, a new component to be analyzed is added, such as that provided by the investigation of (Bélisle, Verónique et Galiano Blanco, Vicentina. 2010), their refer that such a non-integration pattern did not affect the cultural autonomy of Ak’awillay and Pikallact, adding that this cultural boundary may have served as a border between Tiawanaku and Wari in Cuzco, which is why it can be deduced that these cultural integrative elements served as a transition between the sphere of the Wari state and the Tiawanakota macro society; as was also the case of Cerro Baúl in the extreme south of Peru (Bélisle, Verónique et Galiano Blanco, Vicentina. 2010, 143) and (Williams, Isla y Nash 2001, 75-78). Given this evidence of bordering areas and cultural-commercial exchange between the Wari and Tiawanaku processes, we can infer that in this process of joint cultural assimilation.

The toponymic, phonetic and onomastics patterns in the regions promote a diffuse component of determination between what we know today as Aymara language or quechua language, but nevertheless, in the case of Qullasuyu Puquina, there was a more heterogeneous patronymic component with minimal variations between the Yunga and Altiplano derivation. However, this process—in the case of the Wari—is much more complex, given that the cultural drift between the Yunga zone of the western Andes of north Central and south-Central Peru, involves much closer elements, for which reason, to make a theoretical development of differentiation between the Quechua and the Aymara within the formative context of the Jaqu Aru is impossible to determine. In that context, it could be established that the aymara was not a phonetic base Aru, the same that in the spatial and temporal development of the process of occupation and habitability of these ethnically distinct ethnic groups, in complement of union is the semiological and linguistic integration.

Therefore, to agree on an “original” axis between Aymara and Quechua in the region of the southern-central Andes of Peru is impossible to determine. However, in the areas of cultural exchange between the Tiawanaku and the Wari. The process of culturization and interculturization has much more clearly defined differential patterns, since the pictographic, onomastic, architectural, linguistic and cultural representational evidence is much more visible and decisive when it comes to seeing the state or territorial development of these communities, which are predominantly Tiawanaku.

The Puquine societies of the Tiawanakota macro-consolidation; and of which the proto-aymara were not a part during the Early and Late Intermediate Period (Williams, et al. 2009, 624-626).

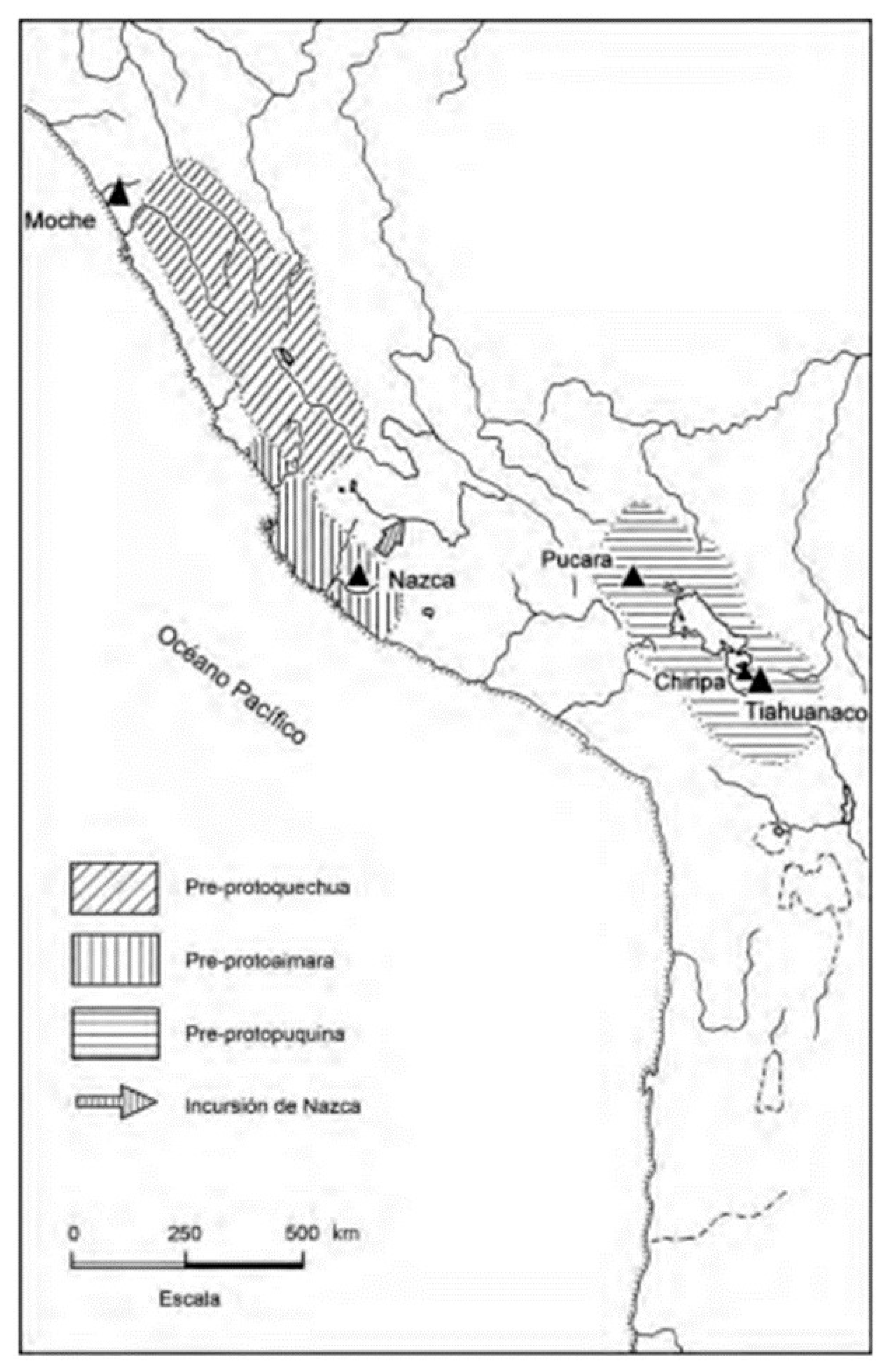

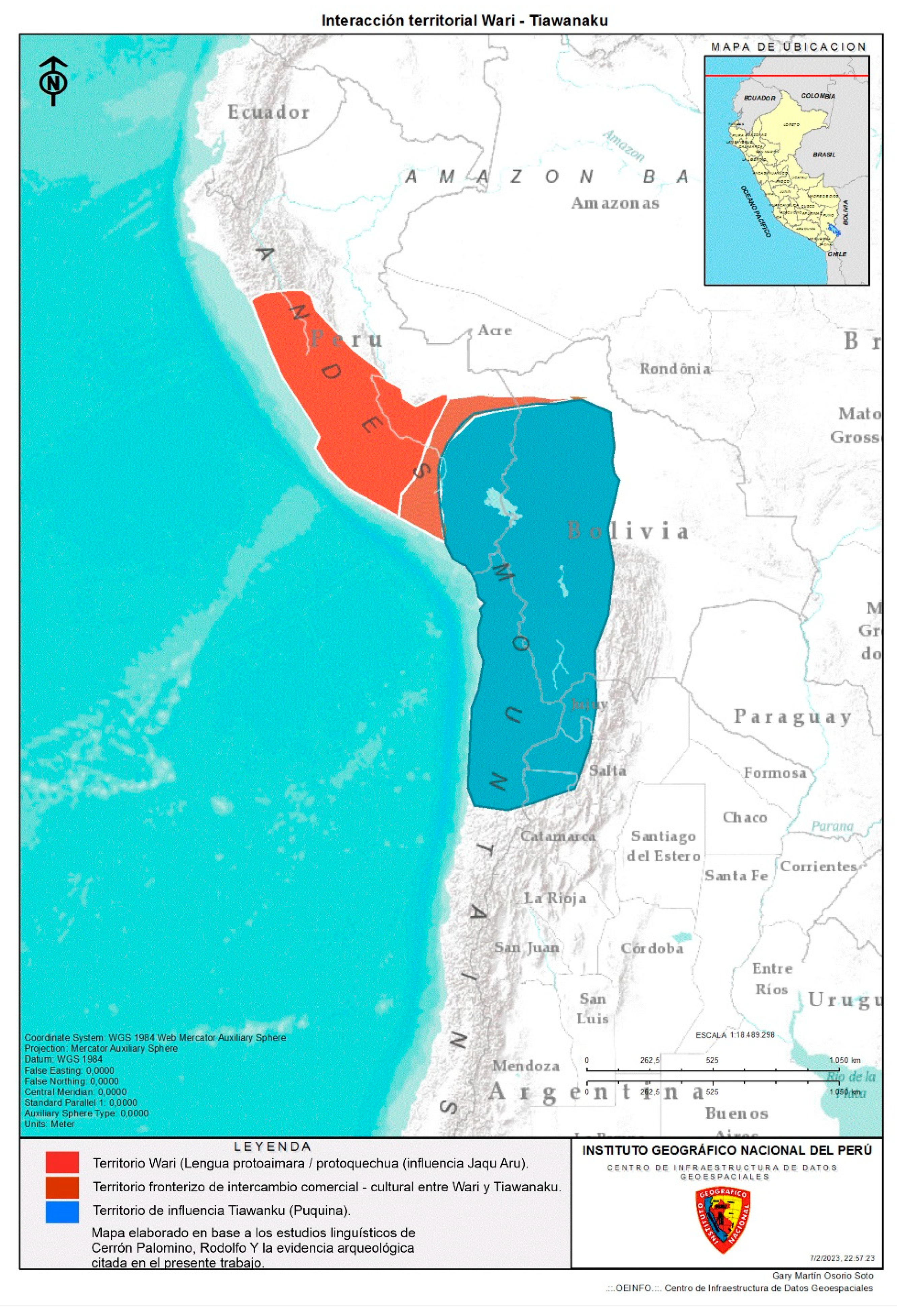

Figure 2.

Map of Wari and Tiawanaku territorial influence during the Middle Horizon in the Pre-Inca period with border articulation zones Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Map of Wari and Tiawanaku territorial influence during the Middle Horizon in the Pre-Inca period with border articulation zones Source: Own elaboration.

In the areas of cultural exchange between Tiawanaku and Wari, the process of culturization and Interculturalization presents much more defined differential patterns, given that, from the pictographic, onomastics, architectural, linguistic and cultural representation evidence is much more visible and decisive when examining the state or territorial development of these communities that have predominance of the Tiawanaku, that is, of puquine societies of the Tiawanakota macro-consolidation; and of which the proto-Aymara did not form part during the Early and Late Intermediate periods.

This differentiation between pictographic elements among the Wari (proto-Aymara / protoquechua) is evident in the archaeological analysis made by (Horta 2004), where the pattern of symbolic representation differs from the symbolic content of the Wari populations, so that this allows a delimitation of the “aymara” component of the Tiawanakota component, mainly during the chronological period between 500 BC to 1,100 AD.

Therefore, from the archaeological perspective, the “aymara” does not correspond to the component of the Qullasuyu region in this period. In addition, as we have mentioned above, the analysis of the ethnic component would confirm that the “aymara” does not correspond to the ethnic elements of the Qullasuyu (Rothhammer, Francisco, Moraga, Mauricio, et al. 2003, 272-273). It is possible to develop the hypothesis that the agglutinating agent of the “aymara” (Wari) was purely linguistic components; even with the uncertainty that this represents. Since it is impossible to differentiate between linguistic elements of Aymara, Protoquechua or Jaqu Aru, a commercial and ceremonial interaction in these border areas between the Aymara (Wari) and Puquina (Tiawanaku) worlds is suggested (Horta 2004, [36], 2010, [28-35]).

The evidence of these pottery records shows a pictorial component typical of the Yunga Puquina communities during the Early Formative period, which is why, given this semiological record, it can be assumed that the cultural elements adopted by the Wari have had two branches of influence, the first from the interculturalization of the Central Andes, and a second one from the bordering areas of Integration of the Tiawanakota—Yunga component of the southern region of the Western Andes, by virtue of the antiquity that these have over the Wari chronological components.

In addition to this, the author makes a difference between the Pukara phenomena and those of the Altiplano region, which does not exclude that these cultural groups were dissociated from each other, but that the Yungas Puquinas groups maintained their own cultural process since the Early Formative period. This cultural component maintained its uniqueness even though they were integrated into the macro-consolidation of Tiawanaku. In this sense, chronologically, the geometric elements in the pictographic representations and cultural elements are older in the coastal settlements of the Qullasuyu than in the central-southern Peruvian Andes. Similarly, these representations with smooth geometric patterns (squares) are earlier than the curved representations of the “protoaimaras” (Horta 2004, 50) and (J. P. Gordillo Begazo 2019, 98-100).

The chronicler Cieza de León (1550) in his chronicle, refers that during the pre-imperial period of the Inca there was an invasion of the Chinchas (Aymara) towards the region of the Collao in the territories corresponding to the Lupacas territories (Cieza de León 1959 (1553), 246-248). This information, according to the description made by (Santa Cruz Pachacuti 1879 (1613)). These invasions would have originated during the intermediate period of the conformation of the government of Çuayna Çápac. The Chinchas (aymara) fought the Lupacas of Chucuito, who were under the local reign of Canchis (Santa Cruz Pachacuti 1879 (1613), 278-281). However, it is striking that, according to the chronicle, this invasion was carried out by a Çápac Inca against the ethnic groups of the Qullasuyu, since the conformation of the Inca originates and emerges from this region towards Cuzco (R. Cerrón Palomino 2013, 50-53, 68).

Therefore, it could be assumed that what the chronicles of this period refer to is a conflict of territorial organization in the face of a separatist uprising of a local ethnic group, given that the Qullasuyu by antonomasia and germination was the mother of the Inca Empire, mainly during the period of the “mythical Incas”. In addition to this we can show that in this period the development of the fortifications or Pucarás demonstrate that, during the implosion of Tiawanaku, the chaos and the struggle for power between some kingdoms for the political hegemony of the Qullasuyan region forged a series of local conflicts for resources and territories in the Collao region, a process that was ordered by the preponderant kingdoms of Lake Titicaca; from where, ethnohistoric evidence affirms, the first Inca emperors were forged (Cornejo Guerrero, Miguel Antonio. 2013, 136-139).

At this point, we cannot affirm an occupation of the “aymara” as an ethnic group within the Collao or the Qullasuyu region, on the contrary, there is evidence of a puquinization of the aymara, a process that lasted until 1420 AD, as long as the construction of a political-state axis, such as the Inca Empire, contributed to the establishment of phonetic components that facilitated the commercial exchange and government between the kingdoms of Chinchaysuyo, Contisuyo and Qullasuyu; reason why, from an anthropological perspective (Branca, Doménico. 2014, 12). Adding a new component to the discussion of: what was really Aymara?

Evidently at this point of the historical process of the “aymara” during the Inca, it is unclear, the conjunction of these linguistic elements makes researchers interpret an aimarization of Quechua or a Quechuaization of aymara, without this being corroborated in a certain way as there is no record of these languages in a concrete way, to determine a chronological component that allows to establish which came first.

However, as for Puquina, the situation is a little clearer, since we know that this language was constant in the development of the Qullasuyu until the middle of the Inca imperial period, where for a practicality of governance, this language was maintained in circles of the Inca imperial elite, while the language of the common people was coupled to the elements of the Jaqu Aru (Aimara and Quechua). However, the onomastics of the Qullasuyu region -as well as its cultural and ritual components-, maintained little altered patterns in terms of cultural and semiological integration of the Aimara-speaking groups; who coupled many cultural elements through cultural appropriation, without generating their identity (Cerrón Palomino, Rodolfo 2004, 11). This cultural drift of the Aymara continued until the final succession of the Inca, without this necessarily meaning that the vernacular language spoken by the common people established a cultural pattern oriented towards a semiological heterogeneity towards the Aymara.

The practicality of a commercial language that allowed for linguistic integration did not necessarily generate its identity or an incipient concept of a “Tahuantinsuyan nation” under the Aymara linguistic domain, as could be seen during the civil wars for the Inca throne and the process of the Conquest.

During the process of conquest of Peru, two components of integration in favor of the company developed by the Spaniards were evidenced, the first one, the collaborationism of the Tumpiz and Chinchas, Tacames and Punas ethnic groups to the conquerors during the siege of Cajamarca and the first trip of Pizarro to Pachacmac and the Chinchas to go to Cuzco, and a second one, the party affiliation to one of the imperial members suppressed by Atabalipa, as it was his brother Huáscar. This collaborationism and social fragmentation within the Empire can mean two concepts close and dissimilar to each other; and simultaneously, which are: A cultural vindication towards the oppression of the Inca Empire, which would result in a sociopolitical support to one of the members of this pre-war diarchy within the Inca imperial structure, that is, a division between the followers of the Qullasuyu, supporters of Huáscar, and another intrinsically linked to Atabalipa, which was composed of elements of the Chinchaysuyo and the Antisuyu (Xerez and Astete 1534, 39-41).

These population elements are difficult to identify due to the diverse processes of mitayaje (mitmacunas) and cultural imposition in the imperial phase, since, territorially, many ethnic groups coexisted under the imperial power of the Inca. Therefore, it is not known in an objective way, which were mitma elements and who were not, in these territorial spaces

iiiii. However, if it is known that during the journey of the first expeditions of the Spaniards to the heart of the empire many of these social groups supported these; as also, and simultaneously, they offered resistance to these (Osorio Soto 2022, 248).

In this sense, it is difficult to establish which of these social components were gravitating to the Aymara and which were not. In addition, we can find references that the heirs of the puquine legacy of Huayna Çápac supported one of the factions of the conquerors, as was the case of Paullu Inca, who was freed from the kidnapping of Atabalipa in one of the temples of the Island of the Sun in the Titicaca, for which reason he—referring to Paullu – supported Almagro during the second phase of the conquest.

Paullu, with his ascent to the throne in Cuzco, reestablished the old puquina order of the empire, an order that came from the period of the “mythical Incas”. The granting of the Royal Tassel to Almagro in a certain way served so that Almagro could be recognized as the representative of the Inca in the territories of Qullasuyu; nevertheless, in this period, Manco Inca, in co-governance with Paullu, chose to support Pizarro

iv, generating again a dispute between the Incas of Qullasuyu and those of Vilcabamba. From the chronicle of Mariño de Lobera (1552) we know that, Almagro had a force of war Indians that corresponded to the territories where the Aymara developed from the time of the Intermediate Horizon

vvi.

These forces of support to the conquest that came from territories of the Aymara speech were immobilized during the expedition of Almagro by the General Order of Almagro, which motivated Almagro to go with a small group of people toward Cañete and of there to Cuzco. This information is known from the expedition made by Diego de Almagro in 1534

viiviii. This marked the first incursions into the territories of southern Peru (Qullasuyu) of linguistic components of the Jaqu Aru (Aymara).

Nevertheless, the report of Alonso Pérez Roldán Rascón (1583) delimits the Aimara language at the moment of the elaboration of the dictionary of the “Aimara Language” made by Alfonso de Xerez (1560-1565) to the territory of Mamara, in the region of Apurimac and the Chinchas

ix, not finding previous elements of this language in the region of the Collao and the Qullasuyu.

Likewise, it is worth mentioning that the reference made by Garci Diez de San Miguel (1567) who indicates that the llactayoc (native to the area) were different from those that had been introduced after the conquest, mainly in the parishes of Sama, Ilabaya, Tarata and Moquegua. The Lupacas of Chucuito did not speak the Aymara language either, but spoke (Sic) "a different dialect"

x.

In the same way, in the report made by Alonso Diez de Ledesma (1578), nephew of Garci Diez de San Miguel, refers that, knowing that his uncle was in the towns of Tarata and “Chiquito” (Chucuito), Juli and Pomata, the Christian doctrine needed to be reinforced, since the local Indians were very different from those who had arrived in the campaigns of Gonzalo Pizarro and Vaca de Castro, who, if they spoke Aymara

xi (Cristóbal Vaca de Castro (Res/262/103) 1542)].

Evidently, the information between 1540-1578, evidences that the incursion of the Aymara in the territory of the Qullasuyu is contemporary to the Spanish presence in these territories; and not, in an “original” way. Furthermore, the emphasis that the doctrines make in pointing out a (sic) different language, the same one that would correspond to Puquina as the linguistic articulatory of this period, calls our attention; besides, the development of the dictionaries of Aymara language for the doctrine were developed mainly for the territories of Pachacamac, Lima, Ayacucho and Apurimac, and not for the Qullasuyu; which allows us to establish a model of linguistic development prominently Puquina, and especially of Puquina Yunga, but not of Aymara (R. Cerrón Palomino 2016, 12). Considering these elements, it can be affirmed that, until the XVI century, the Aymara did not occupy the territory of the Qullasuyu; moreover, as it has become evident, the Aymara is consistent with a linguistic integration, and not with a heterogeneous cultural ethnicity; on the contrary, this linguistic integration cannot be differentiated from other derivations of the Jaqu Aru, nor can it be established which is the patronymic and cultural component that encompasses them (Adelaar, Willem F. H., and Pieter C. Muysken. 2004, 34-38).

As has been developed throughout this work, we cannot establish an “aymara” ethnic-racial component, since there is no aymara nation or culture, but rather a social component that articulates a diversity of cultural elements of other social groups from the formative period to the present. This situation does not ignore or detract from the formative continuum, as an axis of social evolution; however, in the case of the Aymara, it does not seem to be the unifying or forging element of an identity as such.

The dialectic creation of an Altiplano origin of the Qullasuyo, evidences an intentionality of territorial and cultural attribution of a social component that speaks the aymara language and its derivations; especially, when until now, pure elements of aymara have not been registered at a linguistic level, as well as at a cultural level. In such a way that the historical, ethnographic and cultural evidence makes it unfeasible to sustain an “Aymara culture” as well as an “Aymara nation”. The argumentative gaps in aymara history have been filled from dialectical perspectives attached to an ideological segment, even though they currently share territory with the original inhabitants of the Qullasuyu territory, this territory belonged to the puquinas. The cultural appropriation, as the inconsistency of an “Aymara slope” is evidenced from the onomastics and cultural patterns of the Southern Western Andes, especially in the western yungas areas that gravitate to the Titicaca ollada and the Aullaguina region (Espezúa Salmón, Dorian. 2020, 97-98), (Cerrón Palomino, Rodolfo. 2011, 128) y (Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse 2010, 294-296).

The difference on the components cultural-ritual and social, is still visible today, since the misnamed “coastal Aymara” differs from that spoken by the populations transferred from the colonial period to the present. In this sense, the Aymara lacks true elements to sustain its own cultural identity; product of the same inconsistency that its members present regarding the historical process of migration and settlement they suffered, systematically ignoring the linguistic evidence that marks the border between the aymara, the Tiawanaku and the Puquina. This difference is not so visible in the elements between Quechua and Aymara, since, as mentioned, both gravitate to the linguistic elements of the Jaqu Aru.

The contemporaneity of the Aymara, responds to other social elements, the same that did not have a real basis, beyond the story and dialectics; in contrast to the original populations of the Qullasuyu, which do have corroborable and tangible elements from a linguistic, cultural and even biological perspective, scientific elements that transcend the mere story.