1. Introduction

In recent years, entrepreneurship has become an important research topic worldwide. It is considered an important source of economic growth and a prominent factor in socioeconomic well-being [

1]. The main implications of entrepreneurship for society include: creating jobs, reducing poverty, leading innovation, promoting social development, and enhancing economic competitiveness [

2]. At present, China attaches great importance to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship-related activities. The report of the 19th National Congress in 2017 clearly stated the need to promote employment and entrepreneurship for college graduates, proposing to "encourage entrepreneurship to drive employment" and multifaceted measures to help "promote multiple channels of employment and entrepreneurship for college graduates and other youth groups." In 2020, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee again emphasized the need to "improve the guarantee system for promoting entrepreneurship-led employment and multi-channel flexible employment." With the introduction of innovation and entrepreneurship policies, the importance of entrepreneurship education for college students in higher education institutions has also been raised to an unprecedented level. However, the lack of a common understanding of the educational objectives, content, methods, and resources required to develop university students as entrepreneurs has hindered policies and efforts to improve the entrepreneurial intentions and actions of higher education students [

3,

4].

Entrepreneurship can be viewed as the type of planned behavior for which the intention model fits. In the last decade, some authors have noted that entrepreneurship education is a relatively new concept and practice, and research to date has reached conflicting conclusions about its effectiveness and value [

5,

6,

7,

8]. It has been argued that the positive effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions should be given high priority [

9]. In comparison, others have argued that the effect of entrepreneurship education on students' entrepreneurial intentions is not significant or even negative [

10]. Moreover, most existing literature only explores the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions in general terms, failing to distinguish the specific ways entrepreneurship education enhances entrepreneurial intentions. Such research is not rigorous enough.

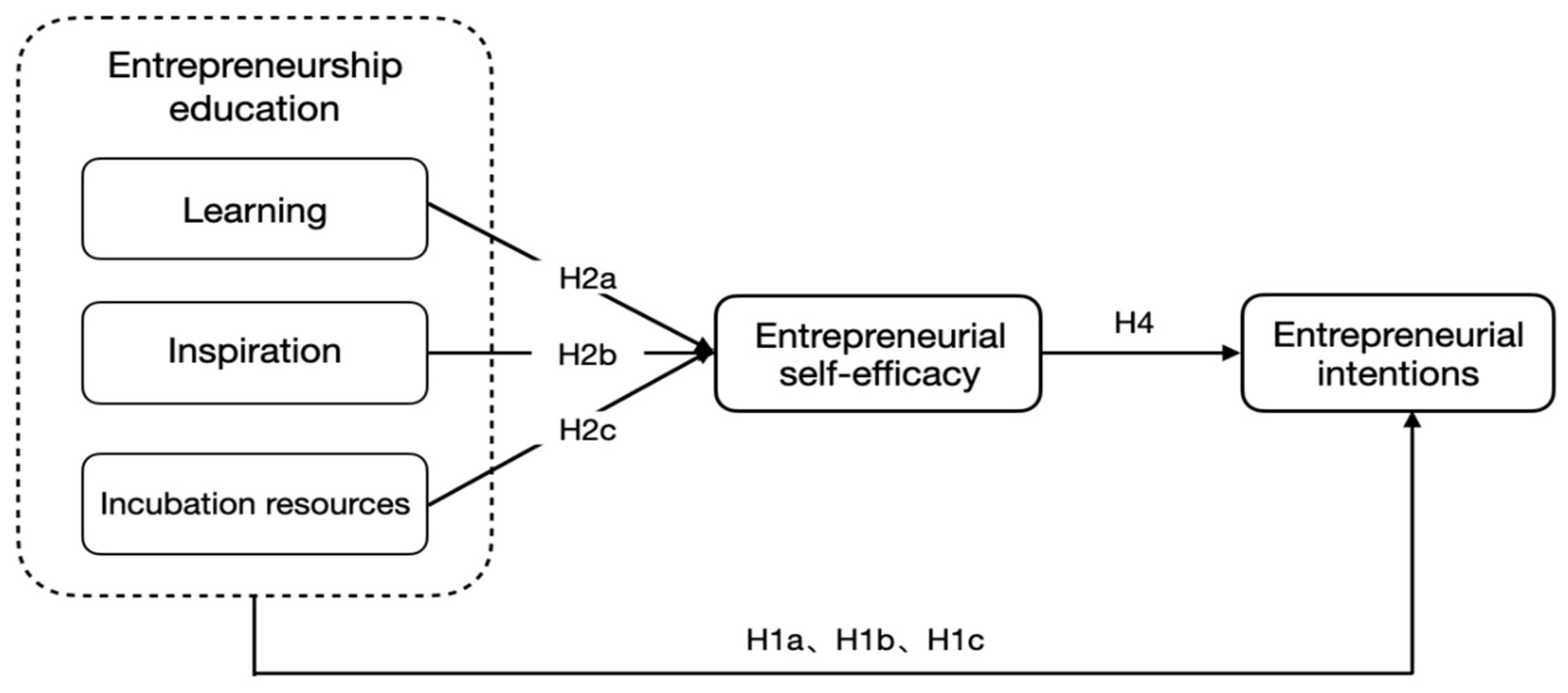

In summary, this study constructs an empirical model of the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students. Since entrepreneurship education is a complex system, a multidimensional division of entrepreneurship education is required. This thesis focuses on the effects of entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources on students' entrepreneurial intentions in higher vocational institutions. In addition, entrepreneurial efficacy is analyzed as a mediating variable to examine the mechanism of its role in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions. The study's findings help expand the scope of entrepreneurship education research and promote the development of an innovative and entrepreneurial economy.

2. Theoretical and Hypothesis

2.1. Entrepreneurship education

Two main theoretical perspectives are used to study the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: human capital and entrepreneurial efficacy theories. The human capital theory emphasizes the skills and knowledge individuals acquire through schooling, vocational training, and other types of experience as determinants of entrepreneurial intentions [

11]. Entrepreneurial efficacy theory links entrepreneurship education to entrepreneurial self-efficacy, suggesting that developing stronger beliefs about one's ability to perform various entrepreneurial roles and tasks successfully increases entrepreneurial intentions [

12]. A review of the literature on entrepreneurship education by Nabi et al. identifies several ways entrepreneurship education may enhance entrepreneurial intentions [

6]. Theoretical evidence and empirical observations suggest that entrepreneurship education positively influences higher education students' sense of efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions in all three areas: entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources.

2.1.1. Entrepreneurial learning

Entrepreneurial learning refers to the acquisition of entrepreneurial knowledge by students in the context of entrepreneurship education [

13]. Entrepreneurship education allows students to engage with a task repeatedly, understand it and learn how to carry it out, and develop confidence in their future success in carrying out the task in question [

12]. For example, students completing entrepreneurship coursework through market analysis, proposing an idea, or writing a business plan, and by learning how to perform these entrepreneurial tasks, they, in turn, develop a greater sense of self-efficacy based on their respective performance. These results have been described as the benefits of entrepreneurial learning. Liang and Shen (2022) confirmed that entrepreneurial learning had a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions through a sample of surveys from the National Assessment of Undergraduate Competencies (NACC, 2016) and that the effect of different entrepreneurial learning styles was similar [

14]. Darmawan and Soetjipto, through a split-class test with students at Santa Natadama University, showed that implementing project-based learning in entrepreneurial learning increased students' entrepreneurial intentions and improved students' entrepreneurial learning outcomes [

15]. Based on this, hypotheses were made:

H1a : Entrepreneurial learning positively affects the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

H2a : Entrepreneurial learning positively influences entrepreneurial efficacy among higher education students.

2.1.2. Entrepreneurial Inspiration

Inspiration is often defined as "the infusion of some idea or purpose instilled into the mind that awakens or creates some impulse" [

16]. While at the entrepreneurial level, Souitaris et al. defined entrepreneurial inspiration as a change of mind (emotion) and thought (motivation) caused by a triggering event or educational input and directed toward considering becoming an entrepreneur [

17]. Triggers can be people (role models, school teachers, guest speakers, entrepreneurs, etc.) or events (educational activities, idea presentations, etc.) [

7]. Nguyen (2021) used a structured model to study 640 students from 11 universities in Vietnam empirically and showed that entrepreneurial extracurricular activities and entrepreneurial inspiration were significantly associated with students' entrepreneurial intentions, while entrepreneurial efficacy partially moderated these relationships [

18].

Research has shown that students can be exposed to entrepreneurial role models through guest speakers and real-life entrepreneurial examples, which motivates them to start their businesses. The role model effect can provide confidence in the obstacles and dilemmas they may encounter in the entrepreneurial process. Entrepreneurship education can inspire students to start their businesses, thus translating into greater entrepreneurial intent. Based on this, hypotheses were made:

H1b : Entrepreneurial inspiration positively impacts the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

H2b : Entrepreneurial inspiration positively influences entrepreneurial efficacy among higher education students.

2.1.3. Entrepreneurial incubation resources

Students can also benefit from business incubation resources, which can help them evaluate their business ideas and develop them into enterprises [

5,

19,

20]. For example, as part of a taught course, students can form a team with a group of students who also have an entrepreneurial idea. This can also be extended to observing and participating in practice through competitions, internships, staying in incubators, and even receiving seed funding from the university. Souitaris et al. show that entrepreneurial incubation resources can stimulate students' entrepreneurial intentions. In contrast, entrepreneurial attitudes mediate before incubation resources and entrepreneurial intentions [

17]. Xu and Wang also validate that the positive effect of resources on the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students [

21]. Using entrepreneurship incubation resources as part of entrepreneurship education and through practice can influence students' perceptions and confidence in entrepreneurship, thus increasing their entrepreneurial intentions. Based on this, the hypothesis was made:

H1c : Entrepreneurship incubation resources positively influence the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

H2c : Business incubation resources positively influence higher education students' sense of entrepreneurial efficacy.

2.2. Entrepreneurial efficacy

Bandura and Cliffs’s (1986) concept of self-efficacy has been considered an important antecedent of entrepreneurial intention [

22,

23,

24]. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy refers to a person's ability to successfully perform the entrepreneurial task role and their expectation of the consequences of creating a new venture [

13]. Entrepreneurial efficacy has a crucial role in explaining entrepreneurial behavior as it plays an influential role in determining an individual's entrepreneurial choices, level of effort, and perseverance. Previous research has also identified entrepreneurial efficacy as a key contributor to entrepreneurial intentions, with Isiwu and Onwuka (2017) examining the impact of psychological factors, including work engagement, self-efficacy, and goal orientation, on female entrepreneurial intentions [

25]. Cross-cultural research found (Pruett et al., 2013) that in an analysis of 1000 university students in the USA, Spain, and China, students had broadly similar perceptions of different aspects of entrepreneurship [

26], but there were interesting and significant differences. Although entrepreneurial intentions were less influenced by cultural and social dimensions, students' self-efficacy strongly predicted entrepreneurial intentions [

26]. Based on this, the hypothesis was made:

H4 : Entrepreneurial efficacy positively influences entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students.

H3a : Entrepreneurial efficacy mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

H3b : Entrepreneurial efficacy mediates between entrepreneurial inspiration and entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

H3c : Entrepreneurial efficacy mediates between entrepreneurial incubation resources and students' entrepreneurial intentions.

In summary, the following theoretical model is proposed (

Figure 1).

3. Research Design

3.1. Research subjects

A web-based questionnaire was used to randomly select college students from seven higher vocational colleges in Zhejiang Province for the study. The schools involved included Zhejiang College of Economics and Technology, Zhejiang Institute of Mechanical and Electrical Technology, Zhejiang College of Tourism Technology, Hangzhou Vocational and Technical College, Wenzhou Vocational and Technical College, Yiwu College of Industry and Commerce, and Zhejiang Institute of Industry and Trade Technology, and the electronic questionnaires were all administered in consultation with teachers were conducted through the e-group after consultation. The survey period is from March to May 2022. A total of 635 university students participated in the survey. After excluding unreasonable data and data that did not comply with the statistical rules, the number of valid questionnaires was 614, with an effective rate of 96.69%, which is extremely representative. The sample was selected by random sampling method, and the survey respondents were regulated in terms of major, grade, and gender to meet the normal distribution of the data.

3.2. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire was compiled by collecting and collating information from scholars at home and abroad, and according to their theoretical views combined with the actual situation of higher education institutions in China. The scale is based on the Likert 5-point scale, where "1~5" means from totally incompatible (totally disagree) to compatible (totally agree). The three dimensions of entrepreneurship education: entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources, are based on Ahmed et al.'s 12-item scale [

12]. The entrepreneurial efficacy of higher education students was measured by drawing on Kumar and Shukla's four-question scale [

24]. In contrast, the entrepreneurial intention of higher education students was measured by drawing on the four question items of Nguyen et al.'s Entrepreneurial Intention Scale [

27]. Typical questions such as "I will do my best to start my own business" and "I am confident in starting my own business," the higher the score, the stronger the intention to start a business and the more likely the student is to start a business in the future.

4. Results analysis

This study conducted a reliability analysis of the questionnaire using SPSS a model fit using AMOS software to validate the relationships, mainly exploring the relationship between the model-independent variables entrepreneurship education (entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources), the mediating variable (entrepreneurial efficacy), and the dependent variable (entrepreneurial intention).

4.1. Exploratory factor analysis

To better ensure the validity of the measurement structure of the data, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the data using the SPSS tool. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the five dimensions of entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, incubation resources, and entrepreneurial efficacy were 0.848, 0.880, 0.834, 0.872, and 0.872, respectively, with coefficients. The coefficients are all higher than 0.8, which shows that the consistency of the indicators is good. In addition, the KMO of the scale was 0.895, indicating that the questionnaire is suitable for factor analysis, Bartlett's sphericity test was significant, and the factor loading coefficients of each observed variable were above 0.6. The results of the factor structure measures in the text all met the requirements, and the whole scale showed good construct validity (

Table 1).

4.2. Validation Factor Analysis

The purpose of the validating factor analysis was to test the consistency of the theory with the data in terms of theoretical hypotheses, thus, to test and ultimately develop the theory.

Table 2 shows results for the standard values of the latent variables in the validated factor analysis for entrepreneurial intent, entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, incubation resources, and entrepreneurial efficacy. The mean-variance extracted (AVE) values are all above 0.5, with the highest AVE value of 0.763 for entrepreneurial intent. Thus, all the items in

Table 2 meet the theoretical criteria and have appropriate validity.

4.3. Correlation Analysis

The results of the correlation analysis are shown in

Table 3, which shows that entrepreneurial learning, inspiration, and incubation resources are significantly correlated with entrepreneurial efficacy and entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial efficacy is also significantly correlated with entrepreneurial intention. The lowest correlation coefficient value is 0.155 for entrepreneurial efficacy to incubation resources, and the highest is 0.550 for entrepreneurial efficacy to entrepreneurial intention. All of the above data passed the significance hypothesis, and the next step will be to conduct an AMOS test on the structural equation model.

4.4. Structural Model Analysis

The evaluation and modification of the model is a key part of the empirical analysis using the structural equation model. The next step was to analyze the fit of the model using AMOS 24.0 software, the results of which are detailed in

Table 4. where the cardinality to freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) was 4.471, which met the reference value, and RMSEA = 0.075, which was between 0.05 and 0.08, indicating a good fit. The NFI, RFI, TLI, CFI, and IFI indicators are all in the range of 0.879 to 0.918, which is ideal. In conclusion, the model fit is good according to the parameters of the model fit.

In addition, combined with the results of the empirical analysis in

Table 5, it can be seen that entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources are all significantly and positively related to entrepreneurial intentions, i.e., hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c hold. Hypotheses H2a and H2b are valid, while incubation resources have no significant effect on entrepreneurial efficacy, and hypothesis H2c is not valid. Hypothesis H4 holds.

4.5. Analysis of the mediating effect

The AMOS software was used to analyze the mediating effect of entrepreneurial efficacy to understand the mediating effect between the dimensions of entrepreneurship education (entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources) and entrepreneurial intentions in higher education. As shown in

Table 6-1, the direct effect of entrepreneurial learning on entrepreneurial efficacy was 0.367 (p=0.005), and the direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurial intention were 0.271 (p=0.002) and 0.141 (p=0.013), respectively, which were significant; the direct effect of entrepreneurial inspiration on entrepreneurial efficacy was 0.199 (p=0.013), and the direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurial intention 0.108 (p=0.015) and 0.077 (p=0.014) respectively, both significant; the direct effect of incubation resources on entrepreneurial efficacy was 0.024 (p=0.631, not significant), and the direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurial intention were 0.097 (p=0.007, significant) and 0.009 (p=0.597, not (not significant). Also, the direct effect of entrepreneurial efficacy on entrepreneurial intention was 0.385 (p=0.014, significant).

Table 6-1.

Results of the analysis of the mediating effect of entrepreneurial efficacy

Table 6-1.

Results of the analysis of the mediating effect of entrepreneurial efficacy

| Mediating Effect |

Learning |

Inspiration |

Incubation

Resources |

Self-efficacy |

| Self-efficacy |

Direct effects |

0.367(0.471)**

<0.005> |

0.199(0.253)**

<0.013> |

0.024(0.029)

<0.631> |

- |

| Indirect effects |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Total effects |

0.367(0.471)**

<0.005> |

0.199(0.253)**

<0.013> |

0.024(0.029)

<0.631> |

- |

| Intentions |

Direct effects |

0.271(0.347)**

<0.002> |

0.108(0.137)**

<0.015> |

0.097(0.115)**

<0.007> |

0.385(0.383)**

<0.014> |

| Indirect effects |

0.141(0.180)**

<0.013> |

0.077(0.097)***

<0.014> |

0.009(0.011)

<0.597> |

- |

| Total effects |

0.412(0.527)**

<0.003> |

0.185(0.234)**

<0.034> |

0.106(0.126)**

<0.009> |

0.385(0.383)**

<0.014> |

From

Table 6-2, the summary of the analysis of the direct, indirect, and total effects of entrepreneurial efficacy shows that the indirect effect of entrepreneurial efficacy between entrepreneurial learning and the entrepreneurial intention was 0.141. The indirect effect between entrepreneurial inspiration and the entrepreneurial intention was 0.077, both of which were partially mediated. At the same time, there was no mediating effect of entrepreneurial efficacy between incubation resources and entrepreneurial intention.

Table 6-2.

Summary of the mediating effects of entrepreneurial efficacy.

Table 6-2.

Summary of the mediating effects of entrepreneurial efficacy.

| Intermediary Effects |

Direct Effects |

Sense of Entrepreneurial Efficacy < Indirect Effect |

Total

Effect |

Type of

Intermediation |

| Learning → Intentions |

0.271 |

0.141

(0.367*0.385) |

0.412 |

Selected Agents |

| Inspiration → Intentions |

0.108 |

0.077

(0.199*0.385) |

0.185 |

Partial Agency |

| Incubation resources → Intentions |

0.097 |

- |

0.097 |

No agent |

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study contributed to social cognitive theory by confirming the influence of 'exogenous factors' on entrepreneurial intentions and testing the mediating role of entrepreneurial efficacy. The results suggest that entrepreneurship education positively impacts the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students and that the three dimensions of entrepreneurship education have different effects. Through the mediating role of over-entrepreneurial efficacy, entrepreneurial learning, and inspiration had a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions, while incubation resources had a direct impact on entrepreneurial intentions.

5.1 Conclusions

Firstly, the study's findings prove that entrepreneurial learning and inspiration gained by higher education students during the entrepreneurship education process can enhance entrepreneurial confidence. This is consistent with Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), according to which self-efficacy is influenced by external factors [

22]. Furthermore, the results validate that the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students are influenced by entrepreneurial self-efficacy and support the mediating role of entrepreneurial efficacy between entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial inspiration, and entrepreneurial intentions.

On the other hand, incubation resources have a direct rather than an indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention. Explaining this, it is understood that entrepreneurial efficacy and intention represent two stages in the cognitive process. The existing literature suggests that entrepreneurial efficacy is a key contributor to entrepreneurial intention [

28]. Therefore, higher education students' perceptions of the importance of incubation resources may play a role in the later stages of entrepreneurship, i.e., when individuals move from entrepreneurial intentions to genuine entrepreneurial behavior, they actively seek resources and become more sensitive to them to succeed in business.

5.2 Implications

Based on the above study, to effectively and efficiently enhance the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions, we should stimulate students' sense of entrepreneurial efficacy and thus enhance their entrepreneurial intentions. Firstly, we should strengthen the entrepreneurial learning of higher education students. Based on the empirical research, it is found that the entrepreneurial learning process of higher vocational students has a significant impact on entrepreneurial intention and self-confidence of successful entrepreneurship. On the one hand, there is a need to provide students with more purposeful and effective entrepreneurship education training to improve their understanding of entrepreneurship and their ability to take on entrepreneurial roles. To this end, entrepreneurship education programs can be designed to engage students in various entrepreneurial learning opportunities, such as business plan writing, business model development, role modeling, and case studies. On the other hand, entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions should be integrated with practice and improve traditional classroom-based entrepreneurial learning. Strengthen the practical training of course teachers, guide them to go deeper into enterprises to understand the cultivation needs of innovative and entrepreneurial professionals, and improve the construction of the curriculum system. Establish an entrepreneurial mentor system and strengthen cooperation between schools and enterprises. Select external mentors to come to campus to provide practical guidance on entrepreneurship to enhance the entrepreneurial self-efficacy of higher vocational students with a richer and more targeted entrepreneurial teaching mode.

Second, inspire students to start their businesses. As an alternative experience, role models can enhance students' sense of entrepreneurial efficacy. When students see similar classmates and entrepreneurs around them achieve success, it inevitably enhances their confidence in entrepreneurship. In other words, entrepreneurial inspiration has more of an impact on entrepreneurial efficacy through teaching techniques and other inspirational activities that make students believe they, too, can become entrepreneurs, rather than students imagining what it would be like to be an entrepreneur. On the one hand, teaching techniques are optimized to build up students' alternative experiences, for example, through case studies, group discussions, and other interactive and communicative approaches to contextual integration and hands-on experience. On the other hand, schools can invite famous entrepreneurs and share their entrepreneurial experiences through activities such as presentations or lectures by distinguished alums and exchange and guidance by outstanding innovation and entrepreneurship mentors inside and outside the university, to inspire students to think about their entrepreneurial ideals and guide them to empathize and self-reinforce, thus enhancing the entrepreneurial intentions of university students in higher education institutions.

Thirdly, fully exploit incubation resources. The empirical results show that incubation resources only impact entrepreneurial intentions but not entrepreneurial efficacy, which is consistent with earlier studies, and that higher education students' awareness of the importance of incubation resources may play a role in the later stages of entrepreneurship. Only a minority of the survey sample had started or were preparing to start a business. Most students were still in the imagination stage of entrepreneurship. While they understood the importance of incubation resources to the success of entrepreneurship, they were not sensitive to the links that run through the whole process of entrepreneurship. By actively using incubation resources as part of entrepreneurship education, on the one hand, higher education institutions should invest more in entrepreneurial practice and bring in a large number of SMEs to participate in practical activities, such as mentoring and leading students on field trips to enterprises and participating in work placements, where students can observe, and even experience to some extent, what it is like to be an entrepreneur by practicing alongside entrepreneurs. On the other hand, the creation of business incubation bases, strengthening the propagation of entrepreneurial policies, increasing the awareness of preferential policies, escorting the entrepreneurial activities of higher education students, and encouraging students to participate in innovation and entrepreneurship practice competitions, through theory combined with practice, which in turn stimulates students' entrepreneurial intentions.

5.3 Limitations

As with all research, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, this study deals with entrepreneurial efficacy and intentions, not actual entrepreneurial behaviors. In social cognitive theory, the intention is the cognitive state that immediately precedes the act of execution. Although many studies have established a plausible link between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behavior, entrepreneurial intention does not imply that actual entrepreneurial behavior will result, and subsequent studies will conduct further longitudinal research on the factors associated with entrepreneurial intention and whether respondents start a business. Secondly, this study selected entrepreneurship education as a prerequisite for entrepreneurial efficacy to test the effect on entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students. Future research could consider other factors, such as background factors, family role models, and barrier factors, which may directly or indirectly affect the entrepreneurial intentions of higher education students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and Z.L.M.; methodology, Z.L.M.; validation, L.L. and Z.L.M.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L.; resources, Z.L.M.; data curation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.M.; supervision, Z.L.M.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. and Z.L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Special Talent Introduction Project "Investigation on the influencing factors and countermeasures of entrepreneurship of students in higher vocational colleges" (No.: R2021002); Zhejiang Federation of Social Science Circles Research Project Results (Project No.: 2023B020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Zhejiang Rural Revitalization Research Think Tank Alliance for helping to collect data of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McMullan, W.; Long, W.A.; Graham, J.B. Assessing economic value added by university-based new-venture outreach programs. Journal of Business Venturing 1986, 1, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.J.; Kuo, T.; Shen, J.P. Exploring social entrepreneurship education from a web-based pedagogical perspective. Computers in Human Behavior 2013, 29, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finardi, U. Clustering research, education, and entrepreneurship: Nanotech innovation at MINATEC in grenoble. Research-Technology Management 2013, 56, 16–20. [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; McNally, J.J.; Kay, M.J. Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing 2013, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. The Academy of Management Learning and Education 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Liñán, F.; Akhtar, I.; Neame, C. Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education 2018, 43, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hulsink, W. Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. The Academy of Management Learning and Education 2015, 14, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Anwar, I.; Saleem, I.; Islam, K.M.B.; Abid, S. Individual entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial motivations. Industry and Higher Education 2021, 35, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.E.; Xu, X.J.; Lin, J. Research on the mechanism of entrepreneurial education to entrepreneurial intention. Studies in Science of Science 2018, 36, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of business venturing 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Klobas, J.E.; Liñán, F.; Kokkalis, P. Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education 2020, 18, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C. Does entrepreneurship education matter students' entrepreneurial intention? A Chinese perspective[C]//The 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering. IEEE 2010, 2776–2779. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.X.; Shen, H. Effects of Entrepreneurial Learning on College Students' Entrepreneurial Intention: Empirical Analysis Based on National Undergraduate Ability Assessment. University Education Science 2022, 10, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Darmawan, I.; Soetjipto, B.E. The implementation of project-based learning to improve entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurship learning outcome of economics education students. Journal of Business and Management 2016, 18, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.A.; Weiner, S.C. (Eds). Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed, vol.7, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business venturing 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.P.; Phan, H.T.T.; Vu, A.T. Impact of Entrepreneurship Extracurricular Activities and Inspiration on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediator and Moderator Effect. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 2014, 38, 217–254. [CrossRef]

- Gaweł, A.; Pietrzykowski, M. Academic education in the perception of entrepreneurship and shaping entrepreneurial intentions. Problems of Management 2015, 13, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.C.; Wang, X.J. Research on the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurship Intention of Vocational College Students—Based on the empirical analysis of 634 samples of vocational college students in Zhejiang Province. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education 2018, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Cliffs, N. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986; pp. 523-582.

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 1994, 18, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shukla, S. Creativity, Proactive Personality and Entrepreneurial Intentions: Examining the Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy. Global Business Review 2019, 097215091984439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiwu, P.I.; Onwuka, I. Psychological factors that influences entrepreneurial intention among women in Nigeria: A study based in South East Nigeria. The Journal of Entrepreneurship 2017, 26, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2009, 15, 571–594. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen A T, Do T H H, Vu T B T, et al. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among youths in Vietnam. Children and Youth Services Review 2019, 99, 186-193.

- Rosique-Blasco, M.; Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Garcia-Perez-De-Lema, D. The effects of personal abilities and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. International entrepreneurship and management journal 2018, 14, 1025–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).