Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

The impacts of seasonal shifts on environments and human behaviors

The impacts of seasonal shifts on climate and peptic ulcers

The impacts of seasonal shifts on work/occupations and industry

The impacts of seasonal shifts on vacation and peptic ulcers

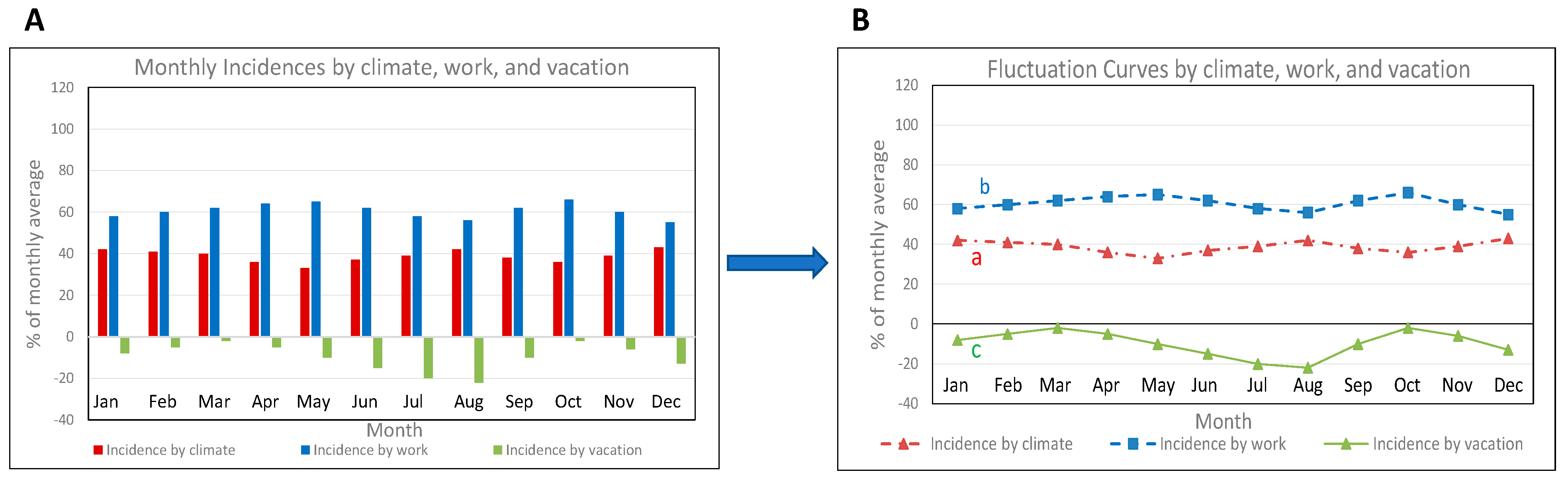

The fluctuation curves caused by individual environmental factors

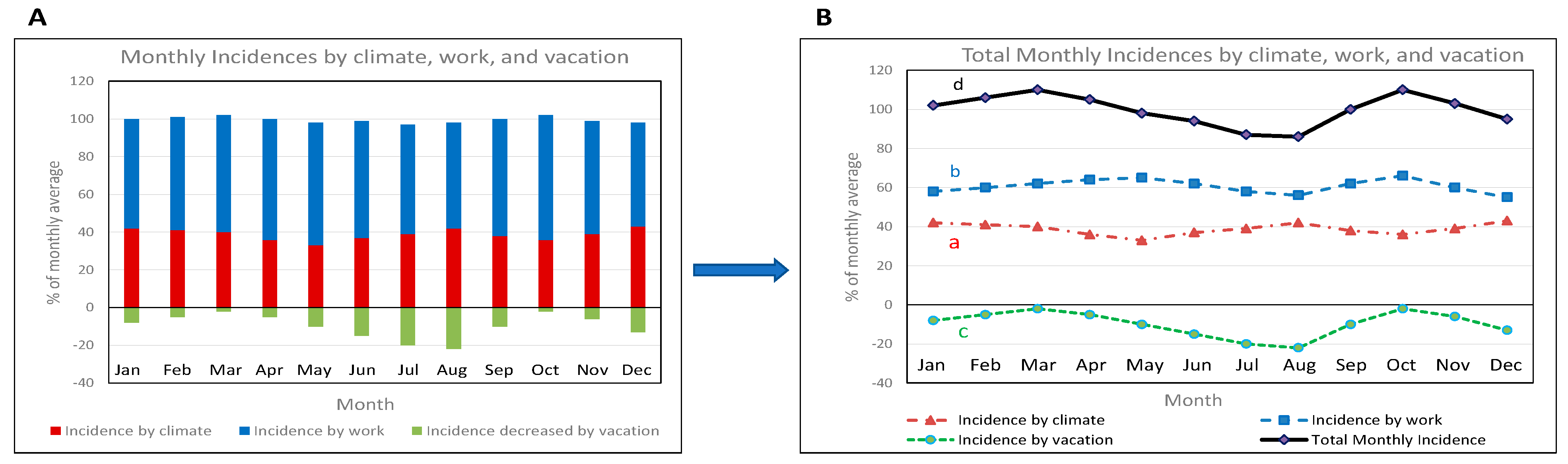

Reproducing the fluctuation curve of a weak seasonal variation

Reproducing the fluctuation curve of the seasonality observed by Sonnenberg

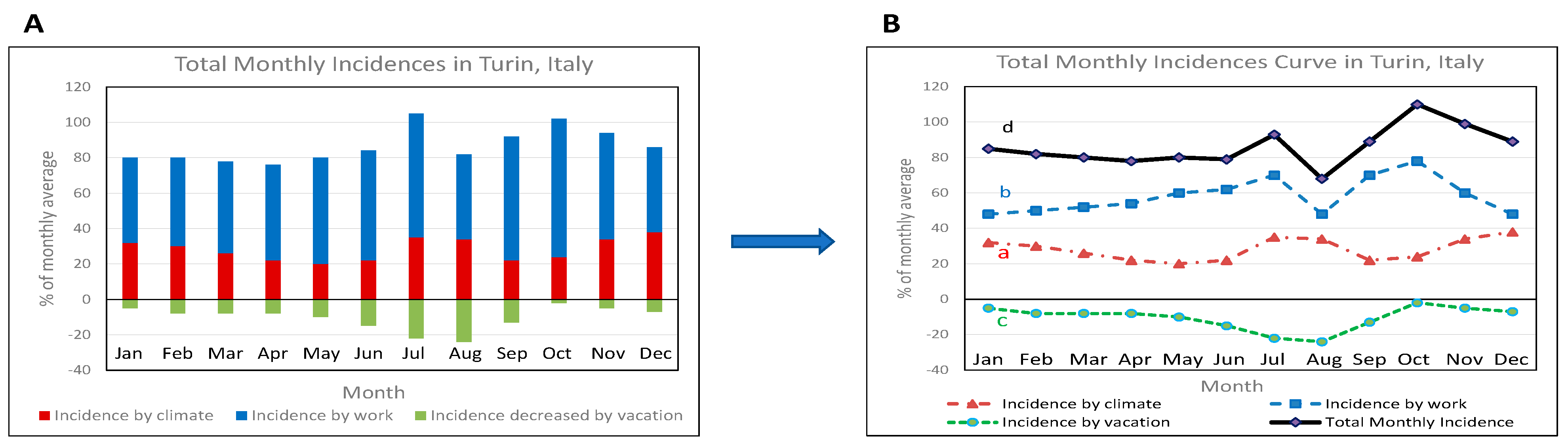

Reproducing the fluctuation curve of the seasonal variation observed by Palmas

Comparison between the birth-cohort phenomenon and seasonal variation

Discussion

The widely believed H. pylori infection may not be the cause of peptic ulcers

A viable analytical method is indispensable to elucidate the seasonal variation

Multiple environmental factors cause the seasonal variation by Superposition Mechanism

Regional differences in environmental factors lead to diverse patterns and controversy

Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibiński, K. A Review of Seasonal Periodicity in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Chronobiol Int, /: 1987 Jan 21;4(1):91–99. Available from: http, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sonnenberg A, Wasserman IH, Jacobsen SJ. Monthly variation of hospital admission and mortality of peptic ulcer disease: A reappraisal of ulcer periodicity. Gastroenterology, /: Oct;103(4):1192–1198. Available from: https, 1192.

- 3. Shih SC, Lin TH, Kao CR. Seasonal variation of peptic ulcer hemorrhage. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei), /: Oct;52(4):258–61. Available from: http, 8258.

- 4. Yoon JY, Cha JM, Kim H Il, Kwak MS. Seasonal variation of peptic ulcer disease, peptic ulcer bleeding, and acute pancreatitis. Medicine (Baltimore), /: ;100(21):e25820. Available from: https, 28 May 2582.

- 5. Dal F, Topal U. Seasonal Pattern of Peptic Ulcer Perforation in Central Anatolia. J Evol Med Dent Sci, /: Aug 2;10(31):2451–2455. Available from: https, 2451.

- 6. Manfredini R, Giorgio R De, Smolensky MH, et al. Seasonal pattern of peptic ulcer hospitalizations: analysis of the hospital discharge data of the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. BMC Gastroenterol, /: Dec 15;10(1):37. Available from: https, 1186.

- 7. Bekele A, Zemenfes D, Kassa S, Deneke A, Taye M, Wondimu S. Patterns and Seasonal Variations of Perforated Peptic Ulcer Disease: Experience from Ethiopia. Ann African Surg, /: Mar 15;14(2):86–91. Available from: https, 1682.

- 8. Yawar B, Marzouk AM, Ali H, et al. Seasonal Variation of Presentation of Perforated Peptic Ulcer Disease: An Overview of Patient Demographics, Management and Outcomes. Cureus, /: Nov 16;13(11). Available from: https, 7708.

- 9. Palmas F, Andriulli A, Canepa G, et al. Monthly fluctuations of active duodenal ulcers. Dig Dis Sci, /: Nov;29(11):983–987. Available from: http, 1007.

- 10. Archimandritis A, Tjivras M, Tsirantonaki M, Kalogeras D, Fertakis A. Symptomatic Peptic Ulcer (PU). J Clin Gastroenterol, /: Apr;20(3):254–256. Available from: http, 0000.

- 11. Kanotra R, Ahmed M, Patel N, et al. Seasonal Variations and Trends in Hospitalization for Peptic Ulcer Disease in the United States: A 12-Year Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Cureus, /: Oct 30;8(10):1–14. Available from: http, 5568.

- 12. Breen FJ, Grace WJ. Bleeding peptic ulcer: seasonal variation. Am J Dig Dis.

- Cohen, MM. Perforated peptic ulcer in the Vancouver area: a survey of 852 cases. Can Med Assoc J, /: 1971 Feb 6;104(3):201–5. Available from: http, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Tzagournis, M. Seasonal and Monthly Incidence of Peptic Ulcer. JAMA J Am Med Assoc, /: 1965 Sep 13;193(11):972. Available from: http, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sezgin O, Altintaş E, Tombak A. Effects of seasonal variations on acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and its etiology. Turk J Gastroenterol, /: Sep;18(3):172–6. Available from: http, 1789.

- 16. Kurata JH, Nogawa AN, Abbey DE, Petersen F. A prospective study of risk for peptic ulcer disease in seventh-day adventists. Gastroenterology, /: Mar;102(3):902–909. Available from: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=1537526&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks%5Cnpapers2, 1537.

- Selye, H. The physiology and pathology of exposure to stress. Oxford, England: Acta; 1950.

- Wolowitz, HM. Oral involvement in peptic ulcer. J Consult Psychol, /: 1967;31(4):418–419. Available from: http, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Susser M, Stein Z. Civilization and Peptic Ulcer. Lancet, /: Jan 20;279(7221):116–119. Available from: http, 7221.

- 20. Doll R, Jones FA, Buckatzsch MM. Occupational Factors in the Aetiology of Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers, with an Estimate of their Incidence in the General Population. Br J Ind Med, /: H. M. Stationery Office; 1951 Oct 1;8(4):308–309. Available from: https, 1951.

- Wretmark, G. The peptic ulcer individual; a study in heredity, physique, and personality. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand Suppl, /: 1953;84:1–183. Available from: http, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, H. Aetiology and pathology of gastric and duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterology, 4: Gastroenterology, 2nd Edition; 1953;1, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feldman M, Weinberg T. Healing of peptic ulcer. Am J Dig Dis, /: Oct;18(10):295–6. Available from: http, 1487.

- 24. Feldman M, Walker P, Green JL, Weingarden K. Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease: a multidimensional case-controlled study. Gastroenterology, /: Dec;91(6):1370–9. Available from: http, 1370.

- 25. Levenstein S, Prantera C, Scribano ML, Varvo V, Berto E, Spinella S. Psychologic predictors of duodenal ulcer healing. J Clin Gastroenterol.

- 26. Carey G, DiLalla DL. Personality and psychopathology: Genetic perspectives. J Abnorm Psychol, /: Available from: http, 1037.

- 27. Tennant C, Goulston K, Langeluddecke P. Psychological correlates of gastric and duodenal ulcer disease. Psychol Med.

- 28. Magni G, Salmi A, Paterlini A, Merlo A. Psychological distress in duodenal ulcer and acute gastroduodenitis. Dig Dis Sci, /: Dec;27(12):1081–1084. Available from: http, 1081.

- Levenstein, S. Stress and peptic ulcer: life beyond helicobacter. Bmj, /: 1998;316(7130):538–541. Available from: http, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Spinella S, Arcà M, Bassi O. Life events, personality, and physical risk factors in recent-onset duodenal ulcer: a preliminary study. J Clin Gastroenterol, l: Apr;14(3):203–210. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP, 0000.

- 31. Bruce Overmier J, Murison R. Anxiety and helplessness in the face of stress predisposes, precipitates, and sustains gastric ulceration. Behav Brain Res.

- 32. Ciacci C, Mazzacca G. The history of Helicobacter pylori: A reflection on the relationship between the medical community and industry. Dig Liver Dis, /: Oct;38(10):778–780. Available from: https, 1590.

- Marshall, BJ. Peptic Ulcer: An Infectious Disease? Hosp Pract, /: 1987 Aug;22(8):87–96. Available from: http, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dong SXM, Chang CCY, Rowe KJ. A collection of the etiological theories, characteristics, and observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers in existing data. Data Br, Inc.; 2018 Aug;19:1058–1067. Available from, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Holcombe, C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut, /: 1992 Apr 1;33(4):429–431. Available from: http, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Savarino V, Mela GS, Zentilin P, et al. Are Duodenal Ulcer Seasonal Fluctuations Paralleled by Seasonal Changes in 24-Hour Gastric Acidity and Helicobacter Pylori Infection? J Clin Gastroenterol, /: Apr;22(3):178–181. Available from: http, 0000.

- 37. Raschka C, Schorr W, Koch HJ. Is There Seasonal Periodicity in the Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori? Chronobiol Int, /: Jan 7;16(6):811–819. Available from: http, 3109.

- Lam, SK. Differences in peptic ulcer between East and West. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, /: 2000 Feb;14(1):41–52. Available from: https, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nomura T, Ohkusa T, Araki A, et al. Influence of climatic factors in the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, /: Jun;16(6):619–623. Available from: http, 1046.

- 40. Liu D-Y, Gao A-N, Tang G-D, et al. Relationship between onset of peptic ulcer and meteorological factors. World J Gastroenterol, /: Available from: http, 1463.

- 41. Yuan X-G, Xie C, Chen J, Xie Y, Zhang K-H, Lu N-H. Seasonal changes in gastric mucosal factors associated with peptic ulcer bleeding. Exp Ther Med, /: Jan;9(1):125–130. Available from: https, 3892.

- 42. FRIED Y, ROWLAND KM, FERRIS GR. The Physiological Measurement of Work Stress: A Critique. Pers Psychol, /: Dec;37(4):583–615. Available from: https, 1111.

- 43. Wu M, Lu J, Yang Z, et al. Ambient air pollution and hospital visits for peptic ulcer disease in China: A three-year analysis. Environ Res, Inc.; 2021 May;196(20):110347. Available from, 20 July 2021. [CrossRef]

- 44. Tom B, Brown M, Chang R. Peptic Ulcer Disease and Temperature Changes in Hawaii. J Appl Meteorol, P: Jun;3(3):311–315. Available from: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/1520-0450(1964)003%3C0311, 1175.

- 45. Kanamori M, Shrader C-H, George S St., et al. Influences of immigration stress and occupational exploitation on Latina seasonal workers’ substance use networks: a qualitative study. J Ethn Subst Abuse, & Francis; 2022 ;21(2):457–475. Available from, 2 May 2022. [CrossRef]

- 46. Huerta-Franco M-R, Vargas-Luna M, Tienda P, Delgadillo-Holtfort I, Balleza-Ordaz M, Flores-Hernande C. Effects of occupational stress on the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol, /: Available from: http, 2150.

- 47. Lin P-Y, Wang J-Y, Shih D-P, Kuo H-W, Liang W-M. The Interaction Effects of Burnout and Job Support on Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) among Firefighters and Policemen. Int J Environ Res Public Health, /: Jul 3;16(13):2369. Available from: https, 2369.

- Salleh, MR. Life event, stress and illness. Malays J Med Sci, /: 2008 Oct;15(4):9–18. Available from: http, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dong SXM, Chang CCY. Philosophical Principles of Life Science. Wunan Cult. Enterp. 2012.

- Xin Min Dong, S. A Novel Psychopathological Model Explains the Pathogenesis of Gastric Ulcers. J Ment Heal Clin Psychol, /: 2022 Sep 24;6(3):13–24. Available from: https, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dong SXM. The Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy of Gastrin and Parietal Cells Induced by Chronic Stress Explain the Pathogenesis of Duodenal Ulcers. J Ment Heal Clin Psychol, /: Aug 9;6(3):1–12. Available from: https.

- 52. Dong SXM. Novel data analysese explain the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers. Preprint, /: Available from: https, 2023.

- 53. Dong SXM. Novel Data Analyses Address the African Enigma and Controversies Surrounding the Roles of Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcers. Preprint, /: Available from: https, 2023.

- 54. Dong SXM. Painting a complete picture of the pathogenesis of peptic ulcers. Jounral Ment Heal Clin Psychol, /: Oct 26;6(3):32–43. Available from: https.

- 55. Tamm M, Jakobson A, Havik M, et al. The Compression of Perceived Time in a Hot Environment Depends on Physiological and Psychological Factors. Q J Exp Psychol, /: Jan 1;67(1):197–208. Available from: http, 1080.

- Fares, A. Global patterns of seasonal variation in gastrointestinal diseases. J Postgrad Med, /: 2013;59(3):203. Available from: http, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, RK. Study of changes in some pathophysiological stress markers in different age groups of an animal model of acute and chronic heat stress. Iran Biomed J, /: 2007 Apr;11(2):101–111. Available from: http, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Luo M, Lau N-C. Characteristics of summer heat stress in China during 1979‒2014: climatology and long-term trends. Clim Dyn, Berlin Heidelberg; 2019 Nov 6;53(9–10):5375–5388. Available from, 2019. [CrossRef]

- 59. Hammer-Helmich L, Linneberg A, Obel C, Thomsen SF, Tang Møllehave L, Glümer C. Mental health associations with eczema, asthma and hay fever in children: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, /: Oct 14;6(10):e012637. Available from: https, 0126.

- Stewart, I. Cold, Hungary and Stressed: The Impact of Poverty on Children this Winter. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hoła B, Topolski M, Szer I, Szer J, Blazik-Borowa E. Prediction model of seasonality in the construction industry based on the accidentality phenomenon. Arch Civ Mech Eng, London; 2022 Feb 21;22(1):30. Available from, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 62. Balestri M, Barresi M, Campera M, et al. Habitat Degradation and Seasonality Affect Physiological Stress Levels of Eulemur collaris in Littoral Forest Fragments. Kamilar JM, editor. PLoS One, /: Sep 17;9(9):e107698. Available from: https, 1076.

- 63. Alananzeh OA, Mahmoud RM, Ahmed MNJ. Examining the Effect of High Seasonality of Frontline Employees: A Case Study of Five Starts Hotels in Aqaba. Eur Sci J.

- 64. Huss-Ashmore R, Goodman JL. Seasonality of work, weight, and body composition. MASCA Res Pap Sci Archaeol, 2: Museum, University of Pennsylvania; 1988;5, 1988.

- 65. Elomaa M, Eskelä-Haapanen S, Pakarinen E, Halttunen L, Lerkkanen M-K. Work-related stress of elementary school principals in Finland: Coping strategies and support. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh, /: ;174114322110103. Available from: http, 3 May 1741.

- 66. Winkelman S, Chaney E, Bethel J. Stress, Depression and Coping among Latino Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health, /: ;10(5):1815–1830. Available from: http, 3 May 1815.

- 67. Arntz M, Wilke RA. Weather-related Employment Subsidies as a Remedy for Seasonal Unemployment? Evidence from Germany. LABOUR, /: Jun;26(2):266–286. Available from: https, 1111.

- 68. Pennino E, Ishikawa C, Ghosh Hajra S, Singh N, McDonald K. Student Anxiety and Engagement with Online Instruction across Two Semesters of COVID-19 Disruptions. J Microbiol Biol Educ, /: Society for Microbiology; 2022 Apr 29;23(1). Available from: https, 2022.

- 69. Colligan TW, Higgins EM. Workplace Stress: Etiology and Consequences. J Workplace Behav Health, /: Jul 25;21(2):89–97. Available from: http, 1300.

- 70. Levenstein S, Rosenstock S, Jacobsen RK, Jorgensen T. Psychological stress increases risk for peptic ulcer, regardless of helicobacter pylori infection or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, Inc; 2015;13(3):498-506.e1. Available from, 2015. [CrossRef]

- 71. Kondo MC, Gross-Davis CA, May K, et al. Place-based stressors associated with industry and air pollution. Health Place, 2014 Jul;28:31–37. Available from, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W. Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease in Wuhan area of China from 1997 to 2002. World J Gastroenterol, /: 2004 Nov 15;10(22):3377. Available from: http, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kühnel J, Sonnentag S. How long do you benefit from vacation? A closer look at the fade-out of vacation effects. J Organ Behav, /: Jan;32(1):125–143. Available from: http, 1883.

- 74. Chen C-C, Petrick JF. Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences. J Travel Res, /: Nov 17;52(6):709–719. Available from: http, 1177.

- 75. Bloom J de, Geurts SAE, Kompier MAJ. Effects of Short Vacations, Vacation Activities and Experiences on Employee Health and Well-Being. Stress Heal, /: Oct;28(4):305–318. Available from: https, 1002.

- Southard, BH. Vacation Time in Europe and America: An Inquiry into Varying Benefit Systems across Cultures. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 77. GilroyDispatch.com. The American vacation [Internet]. GilroyDispatch.com Gilroy California, Dec 07, 2009, /: http, 1580.

- Aron, CS. Working at play: A history of vacations in the United States. Oxford University Press on Demand; 2001.

- 79. Wikipedia. Economy of Turin [Internet]. Free Encycl. /: Aug 23]. Available from: https, 1090.

- 80. Rota MC, Pontrelli G, Scaturro M, et al. Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Rome, Italy. Epidemiol Infect, /: Oct 25;133(5):853–9. Available from: https, 0950.

- 81. Ford, Alexander C.; Tally NJ. Head to Head: Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? Yes. BMJ, /: Aug 14;339(aug14 1):b2784. Available from: https, 2784.

- 82. Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Bardhan KD, Holton J. Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? No. BMJ, /: Aug 14;339(aug14 1):b2788. Available from: https, 2788.

- 83. Record CO, Rubin PC. Controversies in Management: Helicobacter pylori is not the causative agent. BMJ, /: Dec 10;309(6968):1571–1572. Available from: https, 6968.

- 84. Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Tovey FI. Is Helicobacter pylori Infection the Primary Cause of Duodenal Ulceration or a Secondary Factor? A Review of the Evidence. Gastroenterol Res Pract, /: Available from: http, 2013.

- 85. Tovey FI, Hobsley M. Review: is Helicobacter pylori the primary cause of duodenal ulceration? J Gastroenterol Hepatol, /: Nov;14(11):1053–1056. Available from: http, 1053.

- 86. Fang FC, Casadevall A. Reductionistic and Holistic Science. Payne SM, editor. Infect Immun, /: Apr;79(4):1401–1404. Available from: https, 1401.

- 87. Gigch JP Van. Book review: Design of the modern inquiring system—i. r. descartes (1596–1650). Syst Res Behav Sci.

- Flaskerud, JH. Gastric Ulcers, from Psychosomatic Disease to Infection. Issues Ment Health Nurs, Taylor & Francis; 2020 Nov 1;41(11):1047–1050. Available from, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 89. Wikipedia. Emilia-Romagna [Internet]. Free Encycl. /: Aug 23]. Available from: https, 1105.

- Loeb S, Dynarski S, McFarland D, Morris P, Reardon S, Reber S. Descriptive analysis in education: A guide for researchers. (NCEE 2017–4023). Washington, DC: US Dep Educ Inst Educ Sci Natl Cent Educ Eval Reg Assist [Internet]. 2017;(March):1–40. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/? 5733.

| Birth-cohort Phenomenon[52] | Seasonal Variation | |

|---|---|---|

| Similar Features | 1. Important epidemiological observations/phenomena. | |

| 2. Compelling evidence for a causal role of environmental factors in peptic ulcers, which cause the disease by inducing psychological stress. | ||

| 3. Multiple environmental factors cause the phenomenon via Superposition Mechanism; fluctuation curves can be differentiated to reveal a parallel relationship between psychological impacts of individual environmental factors and the mortality/morbidity rates of peptic ulcers. | ||

| 4. Without considering H. pylori infection. | ||

| 5. Implicate that peptic ulcers are not an infectious disease caused by H. pylori infection, but a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress. | ||

| 6. Epitomize the exogenous psychological stress induced by environmental factors. | ||

| Different Features | 1. An epidemiological observation on an annual basis, in which the mortality rates increase and decrease sharply. | 1. An epidemiological observation on a monthly/seasonal basis, in which the incidences increase and decrease slightly. |

| 2. Fluctuation curves were primarily due to extraordinary environmental factors; the annual mortality rates fluctuate within a wide range. | 2. Fluctuation curves were caused by ordinary environmental factors; the monthly incidences fluctuate within a narrow range. | |

| 3. Less diversity: increased mortality rates are maintained by sudden and short-term extraordinary environmental factors. Not a rhythmic phenomenon. | 3. More diversity: increased incidences are maintained by periodic and predictable ordinary environmental factors, causing a rhythmic phenomenon. | |

| 4. Crucial events (extraordinary environmental factors) induce gastric ulcers in ‘ready-to-ulcerate’ individuals. Secondary stressors induce hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells in the stomach, resulting in duodenal ulcers after 3-5 years. | 4. Common events (ordinary environmental factors) induce both gastric and duodenal ulcers in ‘ready-to-ulcerate’ individuals. | |

| 5. Needs more data covering many years and is harder to study, resulting in relatively fewer reports in the existing literature. | 5. Data covering ≥ 3 years is sufficient and easier to study, resulting in many reports in the existing literature. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).