Submitted:

10 February 2023

Posted:

17 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Vascular Health for Reserve

Vascular Supply Mediates Brain Vascular Health

Vascular Supply of the Medial Temporal Lobe

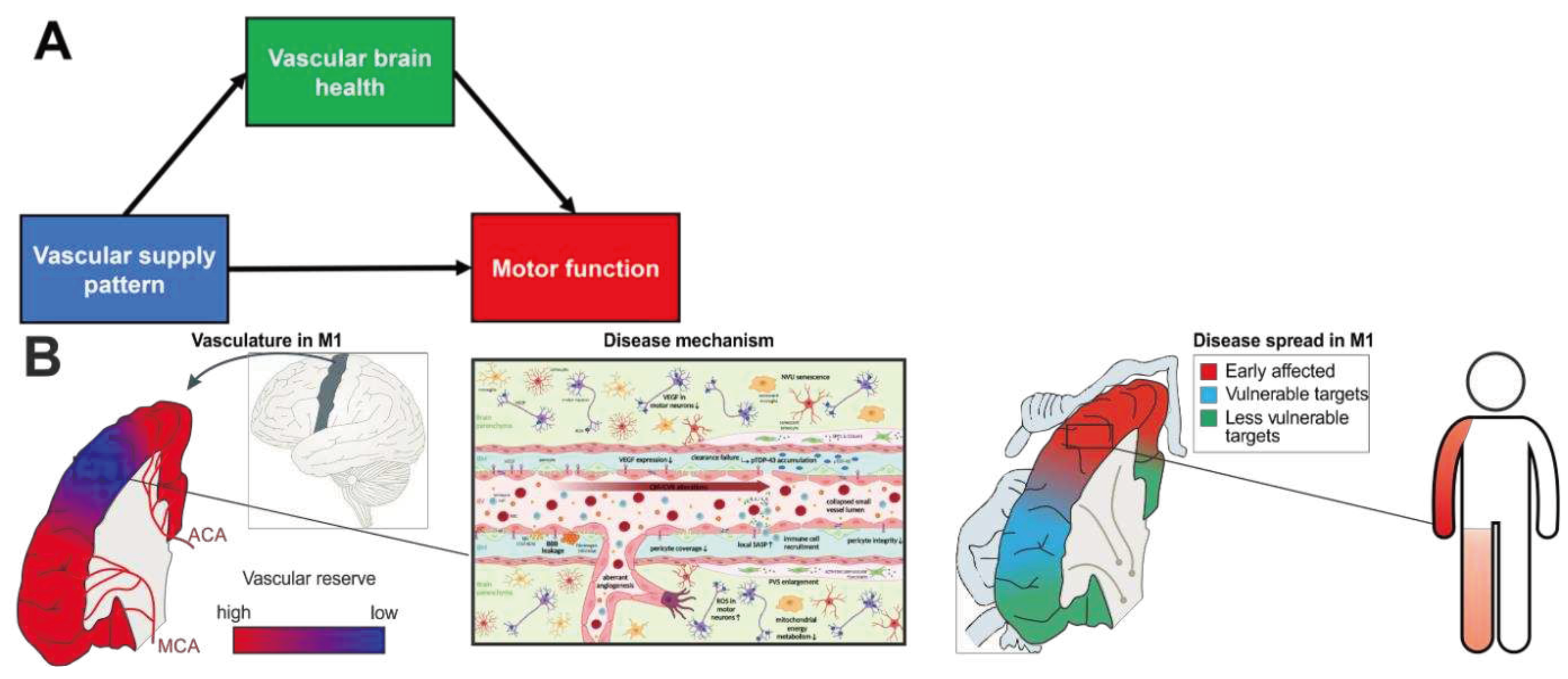

Vascular Supply of the Motor Cortex

Vascular Supply - Molecular and Cellular Underpinnings in ALS

Factors Downstream of Cell Activation in the Neurovascular Unit

In Vivo Imaging of Brain Vascular Health in the Motor Cortex

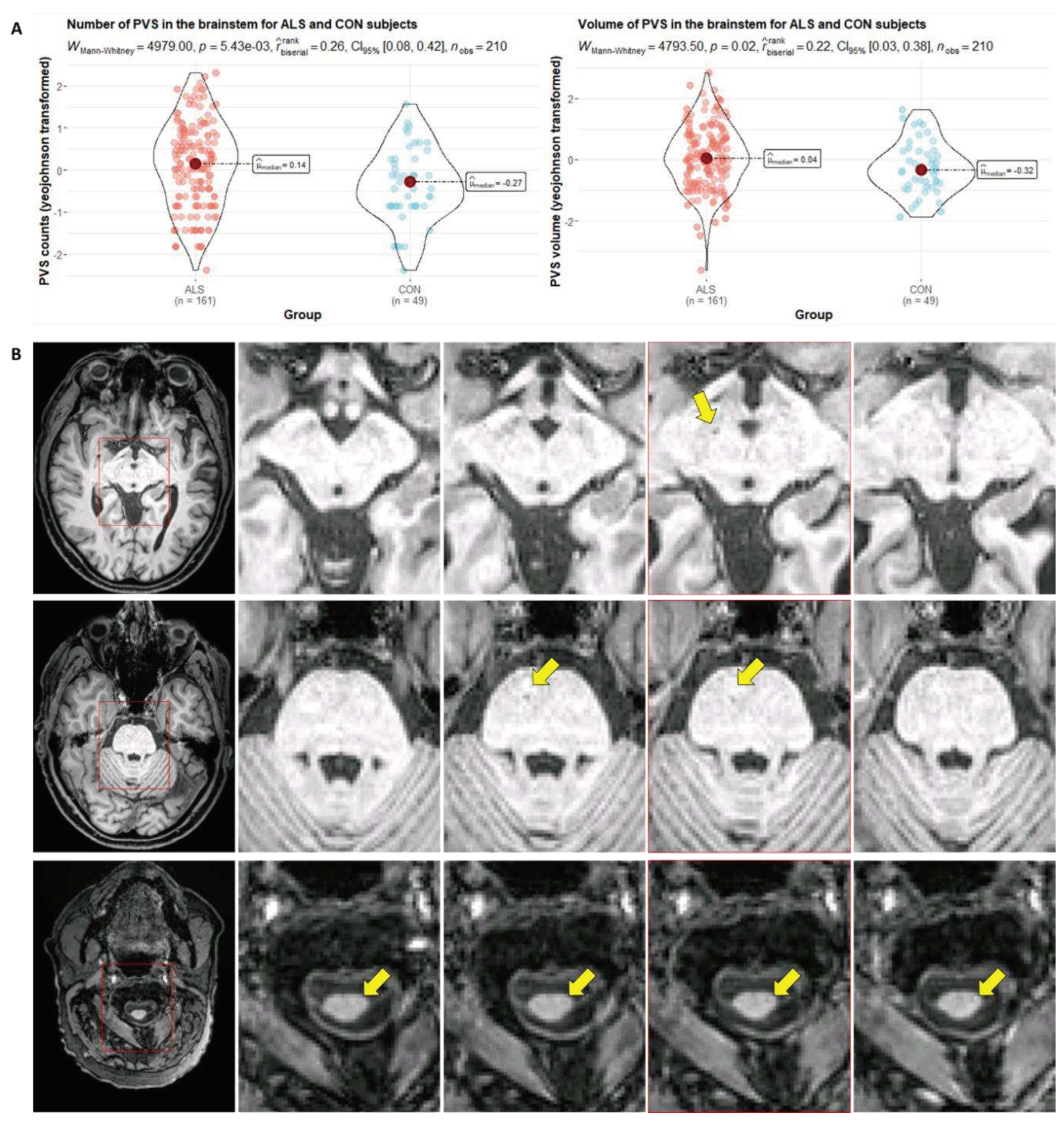

MR Markers of Microvascular Health

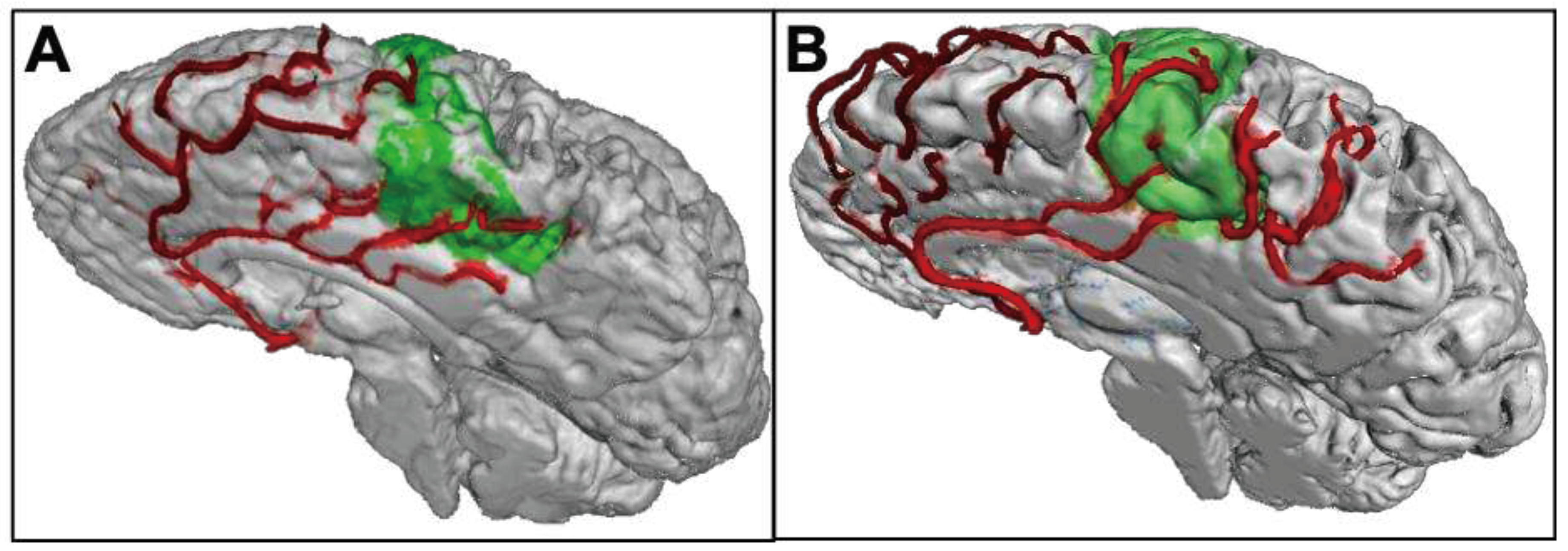

Ultra-High-Resolution MRI to Assess Vascular Supply Patterns

MR-Based Assessment of Resistance and Resilience in ALS

Targeting Brain Vascular Health to Preserve Microvascular Integrity in ALS - Emergent Concepts

Physical Activity & Exercise

Exerkines

Pericyte Restoration

Senotherapeutics

Cell-Based Therapies and Extracellular Vesicles

Concluding Remarks on Vascular Rethinking in ALS Management

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braak, H.; Brettschneider, J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Del Tredici, K. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis--a model of corticofugal axonal spread. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, K.; Handa, H.; Kawakami, K. Multi-phaseted problems of TDP-43 in selective neuronal vulnerability in ALS. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 4453–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravits, J.; Paul, P.; Jorg, C. Focality of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration at the clinical onset of ALS. Neurology 2007, 68, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walhout, R.; Verstraete, E.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Patterns of symptom development in patients with motor neuron disease. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2018, 19, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brettschneider, J.; Del Tredici, K.; Toledo, J.B.; Robinson, J.L.; Irwin, D.J.; Grossman, M.; Suh, E.; van Deerlin, V.M.; Wood, E.M.; Baek, Y.; et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, K.C.; Calvo, A.; Price, T.R.; Geiger, J.T.; Chiò, A.; Traynor, B.J. Projected increase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from 2015 to 2040. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.P.; Brown, R.H.; Cleveland, D.W. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 2016, 539, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganoni, S.; Deng, J.; Jaffa, M.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Wills, A.-M. Body mass index, not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westeneng, H.-J.; Debray, T.P.A.; Visser, A.E.; van Eijk, R.P.A.; Rooney, J.P.K.; Calvo, A.; Martin, S.; McDermott, C.J.; Thompson, A.G.; Pinto, S.; et al. Prognosis for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: development and validation of a personalised prediction model. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedlack, R.S.; Vaughan, T.; Wicks, P.; Heywood, J.; Sinani, E.; Selsov, R.; Macklin, E.A.; Schoenfeld, D.; Cudkowicz, M.; Sherman, A. How common are ALS plateaus and reversals? Neurology 2016, 86, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupillo, E.; Messina, P.; Logroscino, G.; Beghi, E. Long-term survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, R.; Albert, M.; Belleville, S.; Craik, F.I.M.; Duarte, A.; Grady, C.L.; Lindenberger, U.; Nyberg, L.; Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; et al. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: the cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Vemuri, P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: Clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 2018, 90, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Vogel, J.; Schwimmer, H.D.; Marks, S.M.; Schreiber, F.; Jagust, W. Impact of lifestyle dimensions on brain pathology and cognition. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 40, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCombe, P.A.; Garton, F.C.; Katz, M.; Wray, N.R.; Henderson, R.D. What do we know about the variability in survival of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2020, 20, 921–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sever, B.; Ciftci, H.; DeMirci, H.; Sever, H.; Ocak, F.; Yulug, B.; Tateishi, H.; Tateishi, T.; Otsuka, M.; Fujita, M.; et al. Comprehensive Research on Past and Future Therapeutic Strategies Devoted to Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Przybelski, S.A.; Lesnick, T.L.; Graff-Radford, J.; Machulda, M.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Schwarz, C.G.; Lowe, V.J.; Mielke, M.M.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The metabolic brain signature of cognitive resilience in the 80+: beyond Alzheimer pathologies. Brain 2019, 142, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, L.; Mahoney, E.R.; Mukherjee, S.; Lee, M.L.; Bush, W.S.; Engelman, C.D.; Lu, Q.; Fardo, D.W.; Trittschuh, E.H.; Mez, J.; et al. Genetic variants and functional pathways associated with resilience to Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2020, 143, 2561–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palta, P.; Albert, M.S.; Gottesman, R.F. Heart health meets cognitive health: evidence on the role of blood pressure. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Toth, P.; Tarantini, S.; Prodan, C.I.; Sorond, F.; Merkely, B.; Csiszar, A. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: from pathophysiology to public health. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, R.; Xu, Y.; Fitzgerald, O.; Aung, H.L.; Beckett, N.; Bulpitt, C.; Chalmers, J.; Forette, F.; Gong, J.; Harris, K.; et al. Blood pressure lowering and prevention of dementia: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4980–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.C.; Vest, R.T.; Kern, F.; Lee, D.P.; Agam, M.; Maat, C.A.; Losada, P.M.; Chen, M.B.; Schaum, N.; Khoury, N.; et al. A human brain vascular atlas reveals diverse mediators of Alzheimer's risk. Nature 2022, 603, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrits, E.; Giannini, L.A.A.; Brouwer, N.; Melhem, S.; Seilhean, D.; Le Ber, I.; Kamermans, A.; Kooij, G.; Vries, H.E. de; Boddeke, E.W.G.M.; et al. Neurovascular dysfunction in GRN-associated frontotemporal dementia identified by single-nucleus RNA sequencing of human cerebral cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, F.J.; Sun, N.; Lee, H.; Godlewski, B.; Mathys, H.; Galani, K.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, X.; Ng, A.P.; Mantero, J.; et al. Single-cell dissection of the human brain vasculature. Nature 2022, 603, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tada, M.; Cai, Z.; Andhey, P.S.; Swain, A.; Miller, K.R.; Gilfillan, S.; Artyomov, M.N.; Takao, M.; Kakita, A.; et al. Human early-onset dementia caused by DAP12 deficiency reveals a unique signature of dysregulated microglia. Nat. Immunol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, S.M. Vascular Contributions to Brain Health: Cross-Cutting Themes. Stroke 2022, 53, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraszkiewicz, B.; Goszczyńska, H.; Podsiadły-Marczykowska, T.; Piotrkiewicz, M.; Andersen, P.; Gromicho, M.; Grosskreutz, J.; Kuźma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Petri, S.; Stubbendorf, B.; et al. Potential Preventive Strategies for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L.; Goutman, S.A.; Petri, S.; Mazzini, L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2022, 400, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Emerging insights into the complex genetics and pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, K.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Piotrkiewicz, M.; Gromicho, M.; Grosskreutz, J.; Andersen, P.M.; Carvalho, M. de; Uysal, H.; Osmanovic, A.; Schreiber-Katz, O.; et al. Impact of comorbidities and co-medication on disease onset and progression in a large German ALS patient group. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2130–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Ji, H.; Hu, N. Cardiovascular comorbidities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 96, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian, T.H.; Boddy, S.; Islam, M.; Kurz, J.; Whittaker, K.J.; Moll, T.; Harvey, C.; Zhang, S.; Snyder, M.P.; McDermott, C.; et al. A review of Mendelian randomization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2022, 145, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandres-Ciga, S.; Noyce, A.J.; Hemani, G.; Nicolas, A.; Calvo, A.; Mora, G.; Tienari, P.J.; Stone, D.J.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B.; et al. Shared polygenic risk and causal inferences in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Ou, R.; Wei, Q.; Shang, H. Shared genetic links between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and obesity-related traits: a genome-wide association study. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 102, 211.e1–211.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandrioli, J.; Ferri, L.; Fasano, A.; Zucchi, E.; Fini, N.; Moglia, C.; Lunetta, C.; Marinou, K.; Ticozzi, N.; Drago Ferrante, G.; et al. Cardiovascular diseases may play a negative role in the prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Ji, H. Medications on hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 5189–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhak, A.; Hübers, A.; Böhm, K.; Ludolph, A.C.; Kassubek, J.; Pinkhardt, E.H. In vivo assessment of retinal vessel pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, A.F.; Bossen, E.H. Skeletal muscle microvasculature in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 72, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolde, G.; Bachus, R.; Ludolph, A.C. Skin involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 1996, 347, 1226–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, J.; Hutchins, E.; Reiman, R.; Saul, M.; Ostrow, L.W.; Harris, B.T.; van Keuren-Jensen, K.; Bowser, R.; Bakkar, N. Global alterations to the choroid plexus blood-CSF barrier in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coon, E.A.; Castillo, A.M.; Lesnick, T.G.; Raghavan, S.; Mielke, M.M.; Reid, R.I.; Windham, B.G.; Petersen, R.C.; Jack, C.R.; Graff-Radford, J.; et al. Blood pressure changes impact corticospinal integrity and downstream gait and balance control. Neurobiol. Aging 2022, 120, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, M.; Iijima, M.; Shirai, Y.; Toi, S.; Kitagawa, K. Association Between Cerebral Small Vessel Disease and Central Motor Conduction Time in Patients with Vascular Risk. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, D.A.; Mutsaerts, H.J.; Hilal, S.; Kuijf, H.J.; Petersen, E.T.; Petr, J.; van Veluw, S.J.; Venketasubramanian, N.; Yeow, T.B.; Biessels, G.J.; et al. Cortical microinfarcts in memory clinic patients are associated with reduced cerebral perfusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmazer-Hanke, D.; Mayer, T.; Müller, H.-P.; Neugebauer, H.; Abaei, A.; Scheuerle, A.; Weis, J.; Forsberg, K.M.E.; Althaus, K.; Meier, J.; et al. Histological correlates of postmortem ultra-high-resolution single-section MRI in cortical cerebral microinfarcts. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.D.; Castanho, P.; Bazira, P.; Sanders, K. Anatomical variations of the circle of Willis and their prevalence, with a focus on the posterior communicating artery: A literature review and meta-analysis. Clin. Anat. 2021, 34, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, A.; Yaşargil, G.; Roth, P. Microsurgical anatomy of the hippocampal arteries. J. Neurosurg. 1993, 79, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akashi, T.; Taoka, T.; Ochi, T.; Miyasaka, T.; Wada, T.; Sakamoto, M.; Takewa, M.; Kichikawa, K. Branching pattern of lenticulostriate arteries observed by MR angiography at 3.0 T. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2012, 30, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Yuan, C.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Zhao, X. Association Between Incomplete Circle of Willis and Carotid Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 2744–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perosa, V.; Priester, A.; Ziegler, G.; Cardenas-Blanco, A.; Dobisch, L.; Spallazzi, M.; Assmann, A.; Maass, A.; Speck, O.; Oltmer, J.; et al. Hippocampal vascular reserve associated with cognitive performance and hippocampal volume. Brain 2020, 143, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perosa, V.; Düzel, E.; Schreiber, S. Reply: Heterogeneity of the circle of Willis and its implication in hippocampal perfusion. Brain 2020, 143, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vockert, N.; Perosa, V.; Ziegler, G.; Schreiber, F.; Priester, A.; Spallazzi, M.; Garcia-Garcia, B.; Aruci, M.; Mattern, H.; Haghikia, A.; et al. Hippocampal vascularization patterns exert local and distant effects on brain structure but not vascular pathology in old age. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.P.; Brott, T.G.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Meschia, J.F.; Sam, K.; Gottesman, R.F. Collateral Recruitment Is Impaired by Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke 2020, 51, 1404–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tao, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, M.; Wu, B. Circle of Willis Morphology in Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 2022, 13, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugur, H.C.; Kahilogullari, G.; Coscarella, E.; Unlu, A.; Tekdemir, I.; Morcos, J.J.; Elhan, A.; Baskaya, M.K. Arterial vascularization of primary motor cortex (precentral gyrus). Surg. Neurol. 2005, 64 Suppl 2, S48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.; Conti, G.; Jenny, P.; Weber, B. The severity of microstrokes depends on local vascular topology and baseline perfusion. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubart, A.; Benbenishty, A.; Har-Gil, H.; Laufer, H.; Gdalyahu, A.; Assaf, Y.; Blinder, P. Single Cortical Microinfarcts Lead to Widespread Microglia/Macrophage Migration Along the White Matter. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C.C.P.; Lima, N.S. de; da Cruz Pereira Bento, D.; da Silva Santos, R.; da Silva Reis, A.A. A strong association between VEGF-A rs28357093 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a brazilian genetic study. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9129–9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrechts, D.; Storkebaum, E.; Morimoto, M.; Del-Favero, J.; Desmet, F.; Marklund, S.L.; Wyns, S.; Thijs, V.; Andersson, J.; van Marion, I.; et al. VEGF is a modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and humans and protects motoneurons against ischemic death. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, A.; Wharton, S.B.; Fernando, M.; Gelsthorpe, C.H.; Baxter, L.; Ince, P.G.; Lewis, C.E.; Shaw, P.J. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in the central nervous system in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuyse, B.; Moons, L.; Storkebaum, E.; Beck, H.; Nuyens, D.; Brusselmans, K.; van Dorpe, J.; Hellings, P.; Gorselink, M.; Heymans, S.; et al. Deletion of the hypoxia-response element in the vascular endothelial growth factor promoter causes motor neuron degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Hucha, S.; Pastor, A.M.; Morcuende, S. Neuroprotective Effect of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor on Motoneurons of the Oculomotor System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzouz, M.; Ralph, G.S.; Storkebaum, E.; Walmsley, L.E.; Mitrophanous, K.A.; Kingsman, S.M.; Carmeliet, P.; Mazarakis, N.D. VEGF delivery with retrogradely transported lentivector prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Nature 2004, 429, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storkebaum, E.; Lambrechts, D.; Dewerchin, M.; Moreno-Murciano, M.-P.; Appelmans, S.; Oh, H.; van Damme, P.; Rutten, B.; Man, W.Y.; Mol, M. de; et al. Treatment of motoneuron degeneration by intracerebroventricular delivery of VEGF in a rat model of ALS. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Damme, P.; Tilkin, P.; Mercer, K.J.; Terryn, J.; D'Hondt, A.; Herne, N.; Tousseyn, T.; Claeys, K.G.; Thal, D.R.; Zachrisson, O.; et al. Intracerebroventricular delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a phase I study. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbuzova-Davis, S.; Hernandez-Ontiveros, D.G.; Rodrigues, M.C.O.; Haller, E.; Frisina-Deyo, A.; Mirtyl, S.; Sallot, S.; Saporta, S.; Borlongan, C.V.; Sanberg, P.R. Impaired blood-brain/spinal cord barrier in ALS patients. Brain Res. 2012, 1469, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, E.A.; Sengillo, J.D.; Sullivan, J.S.; Henkel, J.S.; Appel, S.H.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown and pericyte reductions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustenhoven, J.; Jansson, D.; Smyth, L.C.; Dragunow, M. Brain Pericytes As Mediators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Korte, N.; Nortley, R.; Sethi, H.; Tang, Y.; Attwell, D. Targeting pericytes for therapeutic approaches to neurological disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S. Alterations of the blood-spinal cord barrier in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathology 2015, 35, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamadera, M.; Fujimura, H.; Inoue, K.; Toyooka, K.; Mori, C.; Hirano, H.; Sakoda, S. Microvascular disturbance with decreased pericyte coverage is prominent in the ventral horn of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2015, 16, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Deane, R.; Ali, Z.; Parisi, M.; Shapovalov, Y.; O'Banion, M.K.; Stojanovic, K.; Sagare, A.; Boillee, S.; Cleveland, D.W.; et al. ALS-causing SOD1 mutants generate vascular changes prior to motor neuron degeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatti, G.C.; Frangini, M.; Valadares, M.C.; Gomes, J.P.; Lima, N.O.; Cavaçana, N.; Assoni, A.F.; Pelatti, M.V.; Birbrair, A.; Lima, A.C.P. de; et al. Pericytes Extend Survival of ALS SOD1 Mice and Induce the Expression of Antioxidant Enzymes in the Murine Model and in IPSCs Derived Neuronal Cells from an ALS Patient. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2017, 13, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månberg, A.; Skene, N.; Sanders, F.; Trusohamn, M.; Remnestål, J.; Szczepińska, A.; Aksoylu, I.S.; Lönnerberg, P.; Ebarasi, L.; Wouters, S.; et al. Altered perivascular fibroblast activity precedes ALS disease onset. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xie, Y.-Z.; Liu, Y.-S. Accelerated aging-related transcriptome alterations in neurovascular unit cells in the brain of Alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 949074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelke, C.; Schroeter, C.B.; Pawlitzki, M.; Meuth, S.G.; Ruck, T. Cellular senescence in neuroinflammatory disease: new therapies for old cells? Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, L.R.; Rentscher, K.E.; Carroll, J.E. Stress-induced biological aging: A review and guide for research priorities. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 104, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunnane, S.C.; Trushina, E.; Morland, C.; Prigione, A.; Casadesus, G.; Andrews, Z.B.; Beal, M.F.; Bergersen, L.H.; Brinton, R.D.; La Monte, S. de; et al. Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 609–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, V.A.; Patani, R. Decoding the relationship between ageing and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a cellular perspective. Brain 2020, 143, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Imai, T.; Munakata, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kanda, F.; Hashimoto, K.; Yamano, T.; Shimizu, N.; Nagao, K.; Yamauchi, M. Collagen abnormalities in the spinal cord from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998, 160, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Andrés-Benito, P.; Carmona, M.; Assialioui, A.; Povedano, M. TDP-43 Vasculopathy in the Spinal Cord in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (sALS) and Frontal Cortex in sALS/FTLD-TDP. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 80, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio, F.; Loon, A.R.; Smeltzer, S.; Benyamine, K.; Navalpur Shanmugam, N.K.; Stewart, N.J.F.; Lee, D.C.; Nash, K.; Selenica, M.-L.B. TDP-43 mediated blood-brain barrier permeability and leukocyte infiltration promote neurodegeneration in a low-grade systemic inflammation mouse model. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapser, J.D.; Spangenberg, E.E.; Barahona, R.A.; Arreola, M.A.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Green, K.N. Microglia facilitate loss of perineuronal nets in the Alzheimer's disease brain. EBioMedicine 2020, 58, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansley, S.; Gu, N.; Guzmán, A.U.; Cai, W.; Wong, C.; Lister, K.C.; Muñoz-Pino, E.; Yousefpour, N.; Roome, R.B.; Heal, J.; et al. Microglia-mediated degradation of perineuronal nets promotes pain. Science 2022, 377, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suttkus, A.; Rohn, S.; Weigel, S.; Glöckner, P.; Arendt, T.; Morawski, M. Aggrecan, link protein and tenascin-R are essential components of the perineuronal net to protect neurons against iron-induced oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morawski, M.; Brückner, M.K.; Riederer, P.; Brückner, G.; Arendt, T. Perineuronal nets potentially protect against oxidative stress. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 188, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemarchant, S.; Pomeshchik, Y.; Kidin, I.; Kärkkäinen, V.; Valonen, P.; Lehtonen, S.; Goldsteins, G.; Malm, T.; Kanninen, K.; Koistinaho, J. ADAMTS-4 promotes neurodegeneration in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forostyak, S.; Forostyak, O.; Kwok, J.C.F.; Romanyuk, N.; Rehorova, M.; Kriska, J.; Dayanithi, G.; Raha-Chowdhury, R.; Jendelova, P.; Anderova, M.; et al. Transplantation of Neural Precursors Derived from Induced Pluripotent Cells Preserve Perineuronal Nets and Stimulate Neural Plasticity in ALS Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirian, A.; Moszczynski, A.; Soleimani, S.; Aubert, I.; Zinman, L.; Abrahao, A. Breached Barriers: A Scoping Review of Blood-Central Nervous System Barrier Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 851563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Zhao, Z.; Montagne, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 21–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnenfeld, H.; Kascsak, R.J.; Bartfeld, H. Deposits of IgG and C3 in the spinal cord and motor cortex of ALS patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 1984, 6, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.R.; Modo, M. Advances in the application of MRI to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 2010, 4, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grolez, G.; Moreau, C.; Danel-Brunaud, V.; Delmaire, C.; Lopes, R.; Pradat, P.F.; El Mendili, M.M.; Defebvre, L.; Devos, D. The value of magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J. Cerebrovascular-Reactivity Mapping Using MRI: Considerations for Alzheimer's Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Nation, D.A.; Kisler, K.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. Imaging subtle leaks in the blood-brain barrier in the aging human brain: potential pitfalls, challenges, and possible solutions. Geroscience 2022, 44, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.; Bright, M.G.; Bulte, D.P.; Figueiredo, P. Cerebrovascular Reactivity Mapping Without Gas Challenges: A Methodological Guide. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 608475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, E.; Stringer, M.S.; Marshall, I.; Wardlaw, J.M.; Thrippleton, M.J. Cerebrovascular Reactivity Measurement Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 643468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.Y.; Woodward, A.; Fan, A.P.; Chen, K.T.; Yu, Y.; Chen, D.Y.; Moseley, M.E.; Zaharchuk, G. Reproducibility of cerebrovascular reactivity measurements: A systematic review of neuroimaging techniques. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2022, 42, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickie, B.R.; Parker, G.J.M.; Parkes, L.M. Measuring water exchange across the blood-brain barrier using MRI. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2020, 116, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Günther, M.; Düzel, E.; Schreiber, S. Microvascular Impairment in Patients With Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Assessed With Arterial Spin Labeling Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Pilot Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 871612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.R.; Benhatzel, C.M.; Stern, L.J.; Hopper, O.M.; Lockwood, M.D. Pilot study utilizing MRI 3D TGSE PASL (arterial spin labeling) differentiating clearance rates of labeled protons in the CNS of patients with early Alzheimer disease from normal subjects. MAGMA 2020, 33, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absinta, M.; Ha, S.-K.; Nair, G.; Sati, P.; Luciano, N.J.; Palisoc, M.; Louveau, A.; Zaghloul, K.A.; Pittaluga, S.; Kipnis, J.; et al. Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.W.J.; Sharp, M.M.; Albargothy, N.J.; Fernandes, R.; Hawkes, C.A.; Verma, A.; Weller, R.O.; Carare, R.O. Vascular basement membranes as pathways for the passage of fluid into and out of the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldea, R.; Weller, R.O.; Wilcock, D.M.; Carare, R.O.; Richardson, G. Cerebrovascular Smooth Muscle Cells as the Drivers of Intramural Periarterial Drainage of the Brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringstad, G.; Eide, P.K. Cerebrospinal fluid tracer efflux to parasagittal dura in humans. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, T.; Naganawa, S. Glymphatic imaging using MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsop, D.C.; Detre, J.A.; Golay, X.; Günther, M.; Hendrikse, J.; Hernandez-Garcia, L.; Lu, H.; MacIntosh, B.J.; Parkes, L.M.; Smits, M.; et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015, 73, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Kisler, K.; Montagne, A.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Abrahao, A.; Heyn, C.C.; Bethune, A.J.; Huang, Y.; Pople, C.B.; Aubert, I.; Hamani, C.; Zinman, L.; Hynynen, K.; et al. Glymphatics Visualization after Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Humans. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 86, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Lirng, J.-F.; Ling, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-F.; Wu, H.-M.; Fuh, J.-L.; Lin, P.-C.; Wang, S.-J.; Chen, S.-P. Noninvasive Characterization of Human Glymphatics and Meningeal Lymphatics in an in vivo Model of Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; John, A.-C.; Werner, C.J.; Vielhaber, S.; Heinze, H.-J.; Speck, O.; Würfel, J.; Behme, D.; Mattern, H. Counteraction of inflammatory activity in CAA-related subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, P.K.; Vatnehol, S.A.S.; Emblem, K.E.; Ringstad, G. Magnetic resonance imaging provides evidence of glymphatic drainage from human brain to cervical lymph nodes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Benveniste, H.; Nedergaard, M.; Zlokovic, B.V.; Mestre, H.; Lee, H.; Doubal, F.N.; Brown, R.; Ramirez, J.; MacIntosh, B.J.; et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Miller, R.G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T.L. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischl, B.; van der Kouwe, A.; Destrieux, C.; Halgren, E.; Ségonne, F.; Salat, D.H.; Busa, E.; Seidman, L.J.; Goldstein, J.; Kennedy, D.; et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2004, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Brady, M.; Smith, S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2001, 20, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, J.; Valdés-Hernández, M.D.C.; Escudero, J.; Duarte, R.; Ballerini, L.; Bastin, M.E.; Deary, I.J.; Thrippleton, M.J.; Touyz, R.M.; Wardlaw, J.M. Assessment of perivascular space filtering methods using a three-dimensional computational model. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022, 93, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, S.; Mattern, H.; Bernier, M.; Robinson, S.D.; Park, D.; Speck, O.; Polimeni, J.R. Imaging of the pial arterial vasculature of the human brain in vivo using high-resolution 7T time-of-flight angiography. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattern, H.; Sciarra, A.; Godenschweger, F.; Stucht, D.; Lüsebrink, F.; Rose, G.; Speck, O. Prospective motion correction enables highest resolution time-of-flight angiography at 7T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-K.; Park, C.-A.; Park, C.-W.; Lee, Y.-B.; Cho, Z.-H.; Kim, Y.-B. Lenticulostriate arteries in chronic stroke patients visualised by 7 T magnetic resonance angiography. Int. J. Stroke 2010, 5, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikse, J.; Zwanenburg, J.J.; Visser, F.; Takahara, T.; Luijten, P. Noninvasive depiction of the lenticulostriate arteries with time-of-flight MR angiography at 7.0 T. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2008, 26, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohmann, R.; Speck, O.; Scheffler, K. Signal-to-noise ratio and MR tissue parameters in human brain imaging at 3, 7, and 9.4 tesla using current receive coil arrays. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 75, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüsebrink, F.; Mattern, H.; Yakupov, R.; Acosta-Cabronero, J.; Ashtarayeh, M.; Oeltze-Jafra, S.; Speck, O. Comprehensive ultrahigh resolution whole brain in vivo MRI dataset as a human phantom. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, M.E.; Bachert, P.; Meyerspeer, M.; Moser, E.; Nagel, A.M.; Norris, D.G.; Schmitter, S.; Speck, O.; Straub, S.; Zaiss, M. Pros and cons of ultra-high-field MRI/MRS for human application. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2018, 109, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feekes, J.A.; Hsu, S.-W.; Chaloupka, J.C.; Cassell, M.D. Tertiary microvascular territories define lacunar infarcts in the basal ganglia. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrikse, J.; Petersen, E.T.; Chng, S.M.; Venketasubramanian, N.; Golay, X. Distribution of cerebral blood flow in the nucleus caudatus, nucleus lentiformis, and thalamus: a study of territorial arterial spin-labeling MR imaging. Radiology 2010, 254, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Garcia, B.; Mattern, H.; Vockert, N.; Yakupov, R.; Schreiber, F.; Spallazzi, M.; Perosa, V.; Speck, O.; Duzel, E.; Maass, A.; et al. Vessel distance mapping: a novel methodology for assessing vascular-induced cognitive resilience. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, H.; Speck, O. ESMRMB 2020 Online, 37th Annual Scientific Meeting, September30–October 2: Lightning Talks / Electronic Posters / Clinical ReviewPosters / Software Exhibits. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 2020, 33, 69–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, H.; Schreiber, S.; Speck, O. Vessel distance mapping for deep gray matter structures. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. virtual meeting. ISMRM. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, C.K.; Yoo, T.; Hiner, B.; Liu, Z.; Grutzendler, J. Embolus extravasation is an alternative mechanism for cerebral microvascular recanalization. Nature 2010, 465, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sances, S.; Ho, R.; Vatine, G.; West, D.; Laperle, A.; Meyer, A.; Godoy, M.; Kay, P.S.; Mandefro, B.; Hatata, S.; et al. Human iPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells and Microengineered Organ-Chip Enhance Neuronal Development. Stem Cell Reports 2018, 10, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsitkanou, S.; Della Gatta, P.; Foletta, V.; Russell, A. The Role of Exercise as a Non-pharmacological Therapeutic Approach for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Beneficial or Detrimental? Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Bello-Haas, V.; Florence, J.M. Therapeutic exercise for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD005229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, P. Physical Activity and Sports in the Prevention and Therapy of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Dtsch Z Sportmed 2020, 71, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Benzi, G.; Dossena, M.; Mutani, R.; Mora, G. Severely increased risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among Italian professional football players. Brain 2005, 128, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, E.J.; Hein, M.J.; Baron, S.L.; Gersic, C.M. Neurodegenerative causes of death among retired National Football League players. Neurology 2012, 79, 1970–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupillo, E.; Messina, P.; Giussani, G.; Logroscino, G.; Zoccolella, S.; Chiò, A.; Calvo, A.; Corbo, M.; Lunetta, C.; Marin, B.; et al. Physical activity and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a European population-based case-control study. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zügel, M.; Weydt, P. Sports and Physical Activity in Patients Suffering from Rare Neurodegenerative Diseases: How Much is too Much, how Much is too Little? Dtsch Z Sportmed 2015, 2015, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Tsang, R.C.C.; Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Gao, Q. Effects of Exercise in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.S.; Gerszten, R.E.; Taylor, J.M.; Pedersen, B.K.; van Praag, H.; Trappe, S.; Febbraio, M.A.; Galis, Z.S.; Gao, Y.; Haus, J.M.; et al. Exerkines in health, resilience and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, T.-I.; Park, H.; Chou, S.-C.; van Vranken, J.G.; Mittenbühler, M.J.; Kim, H.; A, M.; Choi, Y.R.; Biswas, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Amelioration of pathologic α-synuclein-induced Parkinson's disease by irisin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, e2204835119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, H. Irisin improves BBB dysfunction in SAP rats by inhibiting MMP-9 via the ERK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell. Signal. 2022, 93, 110300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, M.; Tan, J.; Pei, X.; Lu, C.; Xin, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhao, F.; Gao, Y.; Gong, Y. Irisin ameliorates neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis through integrin αVβ5/AMPK signaling pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, M.V.; Frozza, R.L.; Freitas, G.B. de; Zhang, H.; Kincheski, G.C.; Ribeiro, F.C.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Clarke, J.R.; Beckman, D.; Staniszewski, A.; et al. Exercise-linked FNDC5/irisin rescues synaptic plasticity and memory defects in Alzheimer's models. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaletto, K.B.; Lindbergh, C.A.; VandeBunte, A.; Neuhaus, J.; Schneider, J.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Honer, W.G.; Bennett, D.A. Microglial Correlates of Late Life Physical Activity: Relationship with Synaptic and Cognitive Aging in Older Adults. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Valaris, S.; Young, M.F.; Haley, E.B.; Luo, R.; Bond, S.F.; Mazuera, S.; Kitchen, R.R.; Caldarone, B.J.; Bettio, L.E.B.; et al. Exercise hormone irisin is a critical regulator of cognitive function. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xuan, R.; Huang, J.; István, B.; Fekete, G.; Gu, Y. Mixed Comparison of Different Exercise Interventions for Function, Respiratory, Fatigue, and Quality of Life in Adults With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 919059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keifer, O.P.; O'Connor, D.M.; Boulis, N.M. Gene and protein therapies utilizing VEGF for ALS. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 141, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Feng, W.; Cai, J.; Gao, J.; Ge, F.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z.; Ding, F.; Marshall, C.; et al. Drainage of senescent astrocytes from brain via meningeal lymphatic routes. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 103, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthiaume, A.-A.; Schmid, F.; Stamenkovic, S.; Coelho-Santos, V.; Nielson, C.D.; Weber, B.; Majesky, M.W.; Shih, A.Y. Pericyte remodeling is deficient in the aged brain and contributes to impaired capillary flow and structure. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omote, Y.; Deguchi, K.; Kono, S.; Liu, N.; Liu, W.; Kurata, T.; Yamashita, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Abe, K. Neurovascular protection of cilostazol in stroke-prone spontaneous hypertensive rats associated with angiogenesis and pericyte proliferation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 92, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Kim, T.-Y.; Yoon, Y.H.; Koh, J.-Y. Pyruvate and cilostazol protect cultured rat cortical pericytes against tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)-induced cell death. Brain Res. 2015, 1628, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.; Zachrisson, O.; Varrone, A.; Almqvist, P.; Jerling, M.; Lind, G.; Rehncrona, S.; Linderoth, B.; Bjartmarz, H.; Shafer, L.L.; et al. Safety and tolerability of intracerebroventricular PDGF-BB in Parkinson's disease patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, T.V.; Williams, A.; Montagne, A. Interplay between Brain Pericytes and Endothelial Cells in Dementia. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1917–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximova, A.; Werry, E.L.; Kassiou, M. Senolytics: A Novel Strategy for Neuroprotection in ALS? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ya, J.; Kadir, R.R.A.; Bayraktutan, U. Delay of endothelial cell senescence protects cerebral barrier against age-related dysfunction: role of senolytics and senomorphics. Tissue Barriers 2022, 2103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsour, M.; Garbuzova-Davis, S.; Borlongan, C.V. Patching Up the Permeability: The Role of Stem Cells in Lessening Neurovascular Damage in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 1196–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandan, N.; Lee, J.-Y.; Garbuzova-Davis, S. Extracellular vesicle-based therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Circ. 2021, 7, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, L.; Gelati, M.; Profico, D.C.; Sorarù, G.; Ferrari, D.; Copetti, M.; Muzi, G.; Ricciolini, C.; Carletti, S.; Giorgi, C.; et al. Results from Phase I Clinical Trial with Intraspinal Injection of Neural Stem Cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Long-Term Outcome. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahao, A.; Meng, Y.; Llinas, M.; Huang, Y.; Hamani, C.; Mainprize, T.; Aubert, I.; Heyn, C.; Black, S.E.; Hynynen, K.; et al. First-in-human trial of blood-brain barrier opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzas, E.I.; György, B.; Nagy, G.; Falus, A.; Gay, S. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, B.; Corduan, A.; Plé, H.; Duchez, A.-C.; Cloutier, N.; Boilard, E.; Provost, P. Activated platelets can deliver mRNA regulatory Ago2•microRNA complexes to endothelial cells via microparticles. Blood 2013, 122, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S.; Talbot, K.; McDermott, C.J.; Hardiman, O.; Shefner, J.M.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Huynh, W.; Cudkowicz, M.; Talman, P.; et al. Improving clinical trial outcomes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, I.; Villate-Beitia, I.; Saenz-Del-Burgo, L.; Puras, G.; Pedraz, J.L. Therapeutic Opportunities and Delivery Strategies for Brain Revascularization in Stroke, Neurodegeneration, and Aging. Pharmacol. Rev. 2022, 74, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140, e596–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.-M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.T.; Williamson, J.D.; Whelton, P.K.; Snyder, J.K.; Sink, K.M.; Rocco, M.V.; Reboussin, D.M.; Rahman, M.; Oparil, S.; Lewis, C.E.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.D.; Pajewski, N.M.; Auchus, A.P.; Bryan, R.N.; Chelune, G.; Cheung, A.K.; Cleveland, M.L.; Coker, L.H.; Crowe, M.G.; Cushman, W.C.; et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappelli, J.; Adhikari, B.M.; Kvarta, M.D.; Bruce, H.A.; Goldwaser, E.L.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Ament, S.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Mitchell, B.D.; et al. Depression, stress, and regional cerebral blood flow. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2023, 271678X221148979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.L.; Poffenberger, C.N.; Elkahloun, A.G.; Herkenham, M. Analysis of cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by chronic social defeat in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.-T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, K.; Murphy, A.; McDonnell, E.; Shapiro, J.; Simpson, E.; Glass, J.; Mitsumoto, H.; Forshew, D.; Miller, R.; Atassi, N. Improving symptom management for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2018, 57, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, M.E.; Nadali, J.; Parouhan, A.; Azarafraz, M.; Tabatabai, S.M.; Irvani, S.S.N.; Eskandari, F.; Gharebaghi, A. Prevalence of depression among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, L.H.; Atkins, L.; Landau, S.; Brown, R.G.; Leigh, P.N. Longitudinal predictors of psychological distress and self-esteem in people with ALS. Neurology 2006, 67, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Moglia, C.; Canosa, A.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; Brunetti, M.; Barberis, M.; Corrado, L.; D'Alfonso, S.; Bersano, E.; et al. Cognitive impairment across ALS clinical stages in a population-based cohort. Neurology 2019, 93, e984–e994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.L.; Thompson, B.J.; Rawlinson, C.; Kumar, P.; White, D.; Serfaty, M.A.; Graham, C.D.; McCracken, L.M.; Bursnall, M.; Bradburn, M.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy plus usual care compared to usual care alone for improving psychological health in people with motor neuron disease (COMMEND): study protocol. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).