Introduction

While the study of “material dhāraṇī”1 has attracted much scholarly attention over the last decade, explorations of such dhāraṇī practices in early Korea2 have been limited by the insufficiency of extant materials from the Unified Silla (676–935), the period when the material dhāraṇī practice gained popularity in China. As studies on material dhāraṇīs gradually opened new avenues of research, especially in the field of Chinese Buddhism, Buddhist incantations that were used in their material forms—inscribed, stamped, and woodblock-printed on paper and silk, or carved on stone monuments—have become essential objects of Buddhist studies. Among the material dhāraṇīs, those carried on the person functioned as a sort of amulet that was believed to bring various efficacies for the bearers.

One of the Buddhist incantations most significant to the study of material dhāraṇīs was the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment (Ch. Suiqiu jide tuoluoni 隨求卽得陀羅尼, Sk. Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī).3 This incantation played an important role in the material culture of medieval Chinese dhāraṇī practice (ca. 600–1000)4 due to the unique practices it created. Handwritten or xylographed, the incantation was often sealed in an armlet. Some such armlets have been found in Tang-period tombs.5 While dozens of amulet sheets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment have been excavated from China, which were made in the Tang (618–907) and the early Song (960–1279) periods, and cases of written Incantations of Wish-Fulfillment have been reported from Japan (Okusa 2012), no such traces from the contemporaneous Korean Peninsula have been found.6 This absence is all the more striking in light of the fact that Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms, one of the two major historical sources of early Korean history, recorded that this particular incantation was recited by Bocheon 寶川 (7th–8th century?), a Silla prince who left the royal court to practice Buddhism on Mount Odea 五臺7 in his later days (Ok Nayeong 2016b, pp. 179-183).8

This incomprehensible absence of Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets in Silla Buddhism has left a gap in our understanding of the medieval East Asian dhāraṇī practice. Last year, however, rare objects were finally discovered that help us to fill this lacuna. In the spring of 2022, one of this paper’s authors, found two amulet sheets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment, long forgotten, in the storage room of the National Museum of Korea (hereafter, NMK).

These newly (re-)discovered amulets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment, one handwritten in Chinese and the other in Indic script, force us to revise our understanding of the dhāraṇī practice in early Korean Buddhism. Hitherto, all known material dhāraṇīs from early Korean Buddhism, with just a few exceptions, were related to the Sūtra of the Pure Light Incantation (Wugoujingguang da tuoluoni 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經). In the Silla kingdom, copies of this sutra were enshrined in pagodas to serve as textual relics since the eighth century (Ju Gyeongmi 2004), a practice unique to the Korean Peninsula and unwitnessed in China until the end of the Tang. Other than the Pure Light Incantations found in the relic crypts of pagodas, little is known about material dhāraṇī practices in early Korea.

The NMK amulets, therefore, offer a rare glimpse into the material dhāraṇī practices of early Korea from a different perspective, one that connects the Korean practice with the broader religious landscape of East Asia in the late medieval period. Probably produced between the eighth and ninth centuries, the amulets suggest that the Silla kingdom formed part of the pan-Asian Buddhist amulet practice that encompassed contemporaneous Asia. At the same time, as will be shown in this paper, the religious context in which these amulets were used was quite different from the Chinese context where the amulets were entombed with the dead for mortuary function. In Silla, the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets were buried in pagodas while keeping their mortuary function of blessing the dead.

Purchase of the Amulets during the Colonial Period

In the spring of 2021, while browsing through the NMK’s digital archive of dry plate photographs from the colonial period (1910–45), we noticed something unusual in one entitled “Fragments of Sanskrit letters from inside the gilt-bronze amulet container excavated from Mount Nam in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province (慶北 慶北 慶州 南山 出土 金銅護符容器 內 梵字文片)” (

Figure 1). Visible in the photograph is a handscroll pasted with two heavily fragmented sheets of paper. The scroll’s left side bears an inscription that reads, “On the right are two kinds of

dhāraṇīs, [each] written in Sanskrit and Classical Chinese script, laid down [on this handscroll] in the seventh year of the Taishō reign” (右梵漢陀羅尼二種立大正七年). The inscription indicates that the

dhāraṇī sheets were mounted into the handscroll in 1918. In the photographed

dhāraṇī sheet written in Chinese, we found the partly remaining title, “

Suiqiu jide da zizai tuoluoni” 隨求卽得大自在陀羅尼, which indicated that the

dhāraṇī was an amulet of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. At Han’s request, the NMK searched for the amulet sheets from the photograph and eventually found them in storage. After our discovery, these rare Buddhist amulets began to attract scholarly attention. The Gyeongju National Museum is currently conducting conservation on the amulets and preparing a special exhibition.

According to our research, the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets entered the collection of the Museum of the Government-General of Korea (Jp. Chōsen sōtokufu hakubutsukan 朝鮮總督府博物館) in 1919, when Korea was under colonial rule. During the colonial period, a large number of ancient artifacts and artworks were acquired by the Museum of the Government-General in Gyeongseong 京城 (present-day Seoul). The Government-General of Korea’s documents related to the museum, now archived in the NMK collection, reveal how the amulets entered the museum. According to the document entitled “The Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Year of Taishō, Documents of Collection Object Requests (大正八,九,十年度 陳列物品請求書),” the museum purchased the “dhāraṇīs written in Sanskrit and Classical Chinese script” (梵漢陀羅尼)” and a “gilt-bronze box” (金銅函) on the eighth day of the eighth month of the eighth year of Taishō (1919).9 This is in line with the indication in the title of the aforementioned photograph that the amulet sheets came from a gilt-bronze box. The Government-General’s document further records that, for the amulets and the box, the museum paid a person named Kim Hanmok 金漢睦2,000 won for each.10

The fact that the amulets were photographed during the colonial period suggests that they attracted some interest from scholars at the museum. During the colonial era, Japanese scholars took dry plate photographs of artifacts from the Museum of the Government-General of Korea and local monasteries for research and publication. Photography at the time, using dry glass plates pre-coated with light-sensitive gelatin, was complex and costly. As was the case for many of the dry plate photographs, it was probably Fujita Ryosaku 藤田亮策 (1892–1960) who ordered the photograph of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets.11 Fujita Ryosaku, an erudite archaeologist and historian, served the Museum of the Government-General from 1922 to 1945, while also working as a professor at Keijō Imperial University 京城帝國大學 in colonial Korea. Because only part of the museum’s collection was photographed during the colonial period, the dry plate photograph of the amulets shows that a Japanese scholar, probably Fujita Ryosaku, took an interest in the amulets.12 After the photograph was taken, however, it seems that no actual research was conducted on the amulets as no report on them was published, as far as we know.

After the purchase, the container, that is, the “gilt-bronze box,” was separated from the amulets sheets, which made us take time to located it. Fortunately, a book entitled

Illustrated History of Korean Art (

Zusetsu Chōsen bijutsushi 図説朝鮮美術史),

13 published in 1941 by Kushi Takushin 久志卓真 (1898–1973), provided clues for finding this “gilt-bronze box.” Kushi Takushin was a connoisseur of fine art, collector, and musician. He published more than a dozen books on East Asian artwork, including Buddhist art, ceramics, antiques and crafts.

14 His

Illustrated History of Korean Art, includes a black-and-white photograph of a square metal box (

Figure 2). According to the explanation that accompanies the photograph, the metal box is a sutra container excavated from Mount Nam, and the box initially contained two sheets of paper, each scribed with

dhāraṇī in Indic and Chinese script and painted with images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas in red pigment (Kushi 1941, p. 190).

15 This suggests that the metal box in the photograph is the “amulet container excavated from Mount Nam” that was purchased together with the two amulet sheets by the Museum of the Government-General of Korea in 1919.

The photograph published in

Illustrated History of Korean Art shows that the metal box’s longitudinal side was engraved with an image of a guardian deity. Dressed in armor with a long fluttering scarf, the deity holds a sword. A halo encircles his head, indicating his divine status. Faintly visible on the lid are engraved patterns of auspicious flowers (

baoxianghua 寶相花/寶相華). The empty background of the box’s entire surface is densely filled with tiny circles of the fish-egg pattern (

eojamun 魚子紋). It turns out that a small gilt-bronze box recently on display in the NMK’s permanent exhibition gallery after conservation and restoration bears exactly the same engravings (

Figure 3), which confirms that is is the NMK amulet sheets’ original container.

Here, a question is raised by the different fates of the amulets and the gilt-bronze container. Why did the amulet sheets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment gradually drift into oblivion after the purchase in 1919, whereas their container was publicly displayed and appeared in publications? One reason is probably the lack of interest in dhāraṇī amulets in the past. As explained above, it is only in recent years that “material dhāraṇīs” have begun to draw scholarly attention. Before the recent “material turn” in academia, scholars of Buddhism usually regarded paper sheets written with dhāraṇīs as superstitious trifles far from the essence of Buddhist teaching. As for the field of Buddhist art history, before art historians’ interest expanded to encompass overall “material culture” in the last few decades, art historians primarily studied fine arts instead of seemingly insignificant amulet pieces. The second reason is the long inaccessibility of the dry plate photographs from the colonial period. After Korea’s liberation in 1945, the dry plate photographs from the colonial period entered the NMK collection. But it was only in 2019 that the NMK made high-resolution digital copies and made a digital archive available to the public.16 As a result, after the liberation of Korea, it took more than a half-century for the existence of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets to finally gain scholarly attention and recognition.

Locating the Two Amulets on East Asian Amulet Culture

Approximately two dozen amulet sheets of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment have been discovered in China, which helps us situate the two amulet sheets from Gyeongju, Korea on the larger map of the material culture of

dhāraṇī in the medieval period. The Chinese amulet sheets, as will be shown in due course, usually feature an image of a deity at their center, sometimes accompanied by a kneeling devotee. The Indic-script amulet from Gyeongju, although heavily fragmented, also shows a standing deity and a kneeling devotee painted in the amulet’s center (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Due to damage to the amulet, the head of the standing deity did not survive, but the

vajra in his right hand remains clearly visible, which indicates that the deity is either

vajrapāṇi bodhisattva or a vajra-warrior. Also discernable is a round necklace around the deity’s neck and a long scarf fluttering along the shoulders and arms. The deity’s bare feet are exposed under his red skirt. The deity is benevolently touching the head of a man in a red robe and a

futou 幞頭, headwear often worn by a court official.

The deity and the man in the amulet from Gyeongju are quite similar to the two figures in the center of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet excavated in Xi’an, China in 1967 (

Figure 6).

17 This amulet from Xi’an is also known as “Jing Sitai’s 荊思泰 amulet” due to the intended beneficiary’s name inscribed on it. The center of Jing Sitai’s amulet features a standing vajra warrior placing his right hand on the head of a man who kneels before him. A fairly large vajra, the attribute of the vajra warrior, is held in his left hand. Just like the standing deity with a vajra in the amulet from Korea, he also wears a round necklace and a billowing scarf, and is dressed in a

dhotī skirt which leaves his bare feet exposed. The figure kneeling before him wears a robe and a

futou headwear, as does the kneeling man in the Korean amulet. Among the scriptures that expounded the efficacies and usages of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment,

18 the scriptural basis of the vajra-holding deity painted in the amulets can be found in the

Scripture Preached by the Buddha on the Dhāranī Spirit-Spell of Great Sovereignty of Immediate Wish Fulfilling translated in 693 by the Kashmiri monk Baosiwei 寶思惟 (Maṇicintana,

19 d. 721) (hereafter, Baosiwei’s scripture) (Copp 2014, p. 112).

20 This scripture explains that a “

vajra deity” (

jingang shen 金剛神) benignly touching the head of a kneeling monk should be drawn in the center of the amulet (T. 20, no. 1154: 642a).

21 Jing Sitai’s amulet bears no inscribed date, but its date has been inferred between the mid to late eighth century based on its iconography, shape, and method of production (An and Feng 1998, Ma 2004, Tsiang 2010, Copp 2014, Kim Bomin 2021).

The Indic-script amulet from Korea has many characteristics that are found in earlier, as opposed to later, amulets of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in China. The dates of the amulets of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment excavated in China range from the mid-eighth to early-eleventh century. However, the earlier ones have no inscribed dates, and those with production dates included in the amulets’ prayer texts mostly appear after the tenth century. The ways in which previous scholarship has inferred the production dates of undated amulets vary. Some scholars have dated them primarily based on their iconography and shape, while others more seriously considered the method of production—whether handwritten, printed, or stamped—for ascertaining their dates. As a result, there is a significant difference of opinion among scholars regarding the inferred date of each amulet (Kim Bomin 2021; Copp 2014; Tsiang 2010; Ma 2004). Nevertheless, differences between earlier and later amulets can be summarized as below (

Table 1).

By comparing this table with the Indic-script amulet excavated from Mount Nam in Gyeongju, Korea, we can see that the Korean amulet possesses more characteristics of the earlier amulets than of the later ones. First, the Indic-script amulet from Korea bears in its center a deity holding the vajra, which usually appeared in earlier amulets, such as Jing Sitai’s discussed above (

Figure 6). On the other hand, in later amulets from China, such as Xu Yin’s 徐殷

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet (926) excavated in Shijiawan 史家灣, Luoyang, and the amulet commissioned by Li Zhishun’s 李知順 in 980, the Bodhisattva of Wish Fulfillment (Dasuiqiu bodhisattva 大隨求菩薩) tends to appear in the amulet’s center, replacing the vajra warrior and the vajra bodhisattva. In these amulets from the tenth century, the eight-armed Bodhisattva of Wish Fulfillment is seated on the lotus. Each hand of the bodhisattva holds a different attribute, such as a sword, a dharma wheel, and a vajra. As an even later example, on the amulet made in 1001 during the Song dynasty, Vairocana Buddha appears in the center, where he forms the wisdom fist mudrā (

zhiquan yin 智拳印) with his two hands, an iconographic sign unique to Vairocana Buddha.

Second, the incantation text surrounding the central images is arranged in a square in both the Indic- and Chinese-script amulets from Korea. This is a trait of earlier amulets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment rather than later ones (see, e.g., Figure. 6). In the later ones, the texts tend to be written in a circular spiral (Kim Bomin 2021). Later Korean amulets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment from the Goryeo period (918–1392) also have texts arranged in a circular form,22 which further suggests that the amulets from Gyeongju were made earlier.

Third, both of the amulets from Korea are manuscripts completely inscribed and painted by hand. This is a feature observed in the earlier amulets. In later amulets, hand-drawn images are mixed with block printing and stamping, as in the amulet excavated in 1975 from a Tang-dynasty tomb found at the Xi’an Smelting Factory (西安冶金機械廠). In this amulet, the central images were painted and colored by hand, while the text of the surrounding incantation was printed by woodblock, as we can see in the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet excavated from a Tang-period tomb found at the Xi’an Smelting Factory. As time passed, both the images and texts in an amulet were printed by woodblock. Copp suggested that the manuscript amulets are from the eighth century, and the completely printed ones are from the ninth and tenth centuries (Copp 2014, pp. 233-237). This observation is notable in that the later Korean amulets from the Goryeo are also woodblock-printed,23 whereas the amulets under discussion here are purely handwritten.

Additionally, the amulets from Gyeongju have simpler designs than the later Chinese ones. For example, they do not have the four heavenly kings that typically appeared in the four corners of later Chinese amulets. Nor do they have the prayer texts framed in a square that we typically find in amulets from the tenth century.

All of these features suggest that the amulets from Mount Nam in Gyeongju were produced during the relatively early stages of this amulet’s development. The dates of the Chinese amulets that demonstrate more characteristics of the early stage than of the late stage (

Table 1) fall between the mid-eighth and ninth centuries, which helps us infer that the amulets from Mount Nam were probably made around that same era. Moreover, the Indic-script amulet from Korea has all four characteristics of the early stage, which suggests that it may have been made in the eighth century. These inferred production dates of the NMK amulets fall neatly into the Silla period, which continued until 935. This inference further conforms to the fact that these manuscript amulets differ greatly from those of the Goryeo in terms of their design and media.

One more factor that supports these NMK amulets’ inferred dates is the aforementioned gilt-bronze box in which the amulets were discovered (

Figure 3). It seems that the box was crafted between the late eighth and early ninth century, because it shares similar decorations and production methods with the gilt-bronze reliquary box excavated from the three-story stone pagoda at Bulguksa 佛國寺 (

Figure 7). The reliquary box from Bulguksa also has a square shape and is decorated with engraved images. Its front and rear panels each portray a three-story stone pagoda, as if representing the pagoda in which it was enshrined, as well as two standing bodhisattvas engraved with thin lines. The background is filled with a fish-egg pattern just like that of the amulet gilt-bronze box from Mount Nam. This pattern appeared on metal crafts in sixth-century Korea and became widespread starting from the eighth century during the Unified Silla. More notable is the way the edges of the amulet box and reliquary box were treated. The edges of both boxes are lined with an unadorned band (Yi Nanyeong 1991). Short diagonal lines were added to the corners of the bands to create the illusion of folded metal plates. The reliquary box from the Bulguksa pagoda was probably made around the late eighth century (Han Jeongho 2008). As the gilt-bronze box would have been crafted to encase the two amulet sheets, we can infer that the amulets were probably made around the same time as the gilt-bronze box, if not earlier.

In sum, we can make a grounded conclusion that both of the amulets excavated from Mount Nam were likely made in the eighth or possibly ninth century. In other words, the dates of the amulets coincide with the Unified Silla period of Korean history. However, this does not necessarily mean that the were crafted in the Silla kingdom, because we cannot rule out the possibility that they were made in China and then brought to the Silla. The possible provenance will be discussed later.

Mystery of the Amulet’s Vanished Image

Judging from the current state of the amulet and its Chinese script, there is no space in the center that could have contained images of a deity and a devotee. Its surviving central parts are densely filled with inscription. This is somewhat unusual, because most Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets have imagery in the center. Other sections of this amulet follow the typical design of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet from the eighth and early ninth centuries; the incantation texts were written to form a squarish spiral; and portrayed as illustrations along the margin of the amulet sheet is an array of ritual objects, weapons, vases, mudrās, and deities on lotuses.

Were the central images originally missing from this amulet? Indeed, careful examination of this heavily damaged amulet reveals that it did initially have images in the center. Before exploring the details of this amulet, though, we should note that the present arrangement of the amulet’s fragments is not quite right. Some pieces are obviously in the wrong position.

24 We should also note that the ink used to create this amulet has been transferred to additional surfaces through the folding of the amulet sheets. Because the amulet sheet was folded into multiple layers to be encased in the gilt-bronze box where it was kept for more than a millennium, the text and images have been transferred to the surfaces that were contacted through the folding. As a result, different Chinese characters overlap throughout the amulet. In order to better show this transference, for readers’ sake, I have captured a detail from the amulet in

Figure 8. The vertical red line in

Figure 8 indicates a fold. The illustration of the sword on the lotus flower was transferred along the fold, creating its mirror image. The Chinese letters were transferred from the right to the left side. I have marked the letters

di 帝 and

yang 洋 so that readers can easily follow how these letters were transferred. In

Figure 8, the left side of the red line is the margin of the amulet where initially only images were drawn on an empty background. This means that the characters transferred to the margin should overlap only with the images, not with other characters. However, some of the characters that have transferred to the margin likely overlapped with another character, as demonstrated by the way in which the letter

mu 暮 (marked in blue boxes) transferred to the left side (

Figure 8).

25 This means that in some places, the ink of the amulet was transferred through multiple layers of the folded paper.

The observation above indicates that the amulet’s center, which probably contained only images against an empty background, would have been imprinted by the text of the incantation transferred from other sections of the amulet, causing the image section to seem to disappear. In this context, a small fragment without any character or figure, marked by a yellow box in

Figure 9, is notable for our research. This fragment, with a height of 2.2 cm and length of 1.2 cm, is currently pasted between other fragments filled with Chinese characters. Upon close examination, this small fragment bears a horizontal black line along the top that seems to frame the central image section, as observed in the aforementioned Jing Sitai’s amulet (

Figure 6) and in others. The black line in this fragment does not continue onto the fragments pasted next to it. This abrupt ending of the line suggests that this small blank fragment was not pasted in the correct place when the amulet sheet’s fragments were reassembled in the colonial era. A similar line is visible below the transferred and overlapped letter, which is marked by an orange box in

Figure 9. The section below this line (marked by a green box) shows less overlapping of Chinese characters than other parts of the amulet, suggesting that this section was originally designed to hold an image against an empty background. Moreover, this section includes flowing curvy lines that are not parts of Chinese characters (marked with green lines in the green box in

Figure 9) and which may be parts of the images that cannot be recognized in this current state.

As for the reason why the small fragment is mostly empty and bears no traces of the drawn image, Han Joung Ho suggests that parts of the image may have been painted with a pigment that could have oxidized and decolorized easily. The pigment used here could have been made of niuhuang 牛黃, or calculus bovis. Also known as ox bezoar, calculus bovis comes from the dried gallstone of cattle and was a costly medicine in East Asia due to its strong sedative effect. As a matter of fact, the aforementioned Baosiwei’s scripture instructs women who want to have a baby boy to draw an image of a male child on the amulet sheet of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment:

If a married woman seeks to give birth to a boy, inscribe it on silk using niuhuang 牛黃; first, inscribe this divine incantation towards the four sides [of the amulet sheet], and in [the incantation text’s center] draw one male child adorned with treasury ornaments. (T. 20, no. 1154: 641c~642a)26

若有婦人求産男者 用牛黃書之於其帛上 先向四面書此神咒 內畫作一童子以寶瓔珞莊嚴

This passage appears in the last part of Baosiwei’s scripture, where the Buddha expounds to Brahma the methods for making inscribed amulets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. The Buddha explains that different images should be drawn on the amulet according to the gender and class of the intended beneficiary. In the above passage, the Buddha says that a woman wishing to have a baby boy should draw a child using pigment made of ox bezoar. The existing amulet sheets from China, however, do not always follow the instructions in the scriptures. By comparing the actual amulets with the scriptures, we can see that there are disparities as well as correspondences between them. In any case, we hope that fluorescence microscopy and further scientific investigations will reveal not only the original images that filled the center of the amulet but also its pigments.

Were They Produced in the Silla or Imported?

Now that we have located the two amulets from Korea within the broader landscape of East Asian amulet culture and inferred the approximate date of their creation, it is time to examine whether they were actually made in the Korean Peninsula. Although they were discovered in the former territory of the Unified Silla kingdom, one must not dismiss the possibility that the amulets were brought from China, because amulets were portable objects that could sometimes cross the frontier. The provenance of the amulets, therefore, should be carefully inferred based on various pieces of suggestive evidence.

Of the two amulets from Silla, the one written in Indic script offers more concrete clues that it was probably fashioned in Silla rather than Tang China. The first clue is the name of the intended beneficiary. Amulets from medieval China often bore the name of the intended beneficiary. In the manuscript and half-manuscript amulets, the beneficiary’s name was often handwritten next to a painted image of the devotee in the amulet’s center. The names were also inscribed in the margin or the incantation text (Copp 2014, pp. 103-139). Such a name, for example, also appears in the amulet in the Yale University Art Gallery collection (Figure 16). Made sometime between 744 and 758 (Ma 2004, p. 530),

27 it is the earliest known example of

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets (Copp 2014, p. 75). The vajra bodhisattva holding a vajra in his left hand is painted in the amulet’s central section, which has been reserved for the painted image. The bodhisattva is benignly resting his right hand on the head of a woman kneeling next to him. The woman probably represents the beneficiary and commissioner of this amulet. The inscription vertically inscribed above her head reads, “The bearer [of this amulet], Madame Wei, wholeheartedly makes an offering” (受持者魏大娘一心供養). It is thought that the kneeling woman representants Madame Wei, the amulet’s beneficiary mentioned in the inscription. At the upper right of the central section is another inscription, stating “Respectfully received [the amulet] at the age of 63” (奉持載六十三).

28 As for Jing Sitai’s amulet examined above, the name Jing Sitai was written multiple times on the amulet. A sizable inscription of the name appears in the right margin of the amulet (green box in

Figure 6). The same name written in Chinese was added in the nine empty pre-made spaces of the Indic-script amulet (two examples are marked with green boxes in

Figure 6).

29

We can also find a trace of the intended beneficiary’s name in the Indic-script amulet from Korea, but the name seems to be a Silla person’s. Originally, an inscription was written next to the aforementioned kneeling figure in the red robe and the futou, who represents the amulet’s intended beneficiary (Figures 5). Only the last three Chinese characters of the inscription survive, but the first one is illegible. The remaining two are jil (Ch. chii 叱) and ji (Ch. zhi 知). The character jil was frequently used when transliterating the names of Silla people in Chinese script. The character ji is an honorific suffix added after the name of a person of high official rank or noble class. The characters ji (Ch. zhi 知) and ji (Ch. zhi 智), used interchangeably, were the most common honorific suffix in epigraphic records from the Silla kingdom (Ju Bodon 1984; Yi Janghui 2003). Thus, the inscription strongly suggests that the kneeling devotee represents a Silla figure. The Silla court adopted Chinese-style official clothing and headwear in 649 during the reign of Queen Jindeok 眞德 (r. 647–654). By the time the amulet was made in the eighth century, or ninth century at the latest, it would have been natural to represent a Silla official dressed in a Chinese-style robe of a court official and a futuo.

Nevertheless, we should consider one more possibility—namely, that the central section’s image and the inscription were added to an amulet imported from abroad. In medieval China, an individual sometimes obtained a mass-produced amulet with an empty central section and had his name and image added to it (Bomin Kim 2018, p. 14). These amulets clearly show how the amulets were mass-printed using a woodblock and later individualized by whoever purchased or obtained the printed sheet. The Indic-script amulet from Korea, however, was not woodblock-printed in any part; it was entirely handwritten and hand-drawn. This decreases the possibility that only the image part and the devotee’s name were added later in Korea. As far as I know, archaeologists have yet to find a handwritten amulet of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment whose central section was left empty for the addition of an image by a later purchaser.

The Indic script amulet from Korea has one more feature that suggests its Korean provenance— the style of its Indic script. At the request of the Gyeongju National Museum, Dr. Han Jaehee, a specialist in early Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism, is currently translating the amulet’s text into Korean and English, which will be published by the museum in a book-length bilingual report. According to Han and the European epigraphists he consulted, the style of the letters in this amulet is different from any Indic script style known today. The calligrapher was not very skilled in writing Indic script, and some letters were done clumsily. These details suggest that the amulet’s letters were possibly made by a Silla monk who copied an Indic-script Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment without fully understanding the script.30

It seems that Indic script was much better calligraphed in Chinese

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets. For example, the Indic letters in the aforementioned Madame Wei’s amulet were written by a trained hand (

Figure 10). By comparing the characters on Madame Wei’s amulet and the amulet from Silla, we can clearly see the difference. Upon enlarging the photographs until the fibers of the silk and paper on which the amulets were written become visible, the difference in the calligraphy becomes obvious (

Figure 11). In Madame Wei’s amulet, we can see the elegant tapering at the ends of lines, which is the trace of quick hand movement. The thickening and thinning of the line shows the nuanced control of the brush. On the Silla amulet, by contrast, the characters do not show such nimble movement; the thickness of the line shows no variations. Some characters in the last line in

Figure 11 look like more like pseudo characters made of lumbering emulation.

The devotee’s name and the Indic letters’ clumsy style, therefore, suggest that this amulet was made in the Silla dynasty rather than brought from abroad. In addition, the objects painted along the amulet’s margin are also rather unique. They are portrayed as if placed on a pole stemming from a rectangular red pedestal (

Figure 4 left). This type of pedestal is not found in amulets from China, including the Turfan area. The size of the amulet from Silla is also larger than contemporaneous Chinese amulets. While the Indic script amulet from Mount Nam has inscriptions and relatively clear features that suggests its Silla provenance, the provenance of the other amulet is harder to judge due to the heavy transference of images and texts (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). The inference of the latter’s provenance will have to wait until its restoration and scientific analyses offer more information.

31

From the Tomb or the Pagoda?

It is fortunate that the gilt-bronze box which contained the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets from the Silla remains in the NMK collection, as it enables us to better understand the Buddhist amulet practices of the period (

Figure 4). Why were the amulets placed in a container? Was this practice unique to the Korean peninsula, or were there similar practices in China where the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment was circulated earlier? Does the practice have any scriptural basis? In order to better understand the NMK amulets, we should locate them in the larger landscape of Buddhist practice surrounding the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment by examining the amulet sheets from cross-cultural perspectives. Unlike the great majority of other material

dhāraṇī used in China, amulets of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment have often been found sealed in an armlet. Wearing an inscribed incantation on one’s body in an armlet was a distinctive practice unique to the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. Some were worn on the arm of a tomb occupant to wish for good rebirth (Copp, 2014, pp. 59-140). Yet, as we will explore below, the amulets from Silla seem to have been used in a modified context, because they probably came from a pagoda’s relic crypt. At the same time, even when placed in pagodas, the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets in Silla still had a mortuary function, as did the Chinese amulets buried in tombs.

In China, the great majority of the surviving containers of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets are armlets (and some are necklace pendants). For example, the Monk Shaozhen’s 丘僧少貞 amulet excavated in 1999 from Sanqiao Town 三橋鎮 near Xi’an was discovered folded and encased in a bronze armlet. The armlet was engraved with vine and fish-egg patterns (Huo 1867, p. 87; Zhou 2000, p. 146; Tsiang 2010, pp. 227-229). A silk amulet of a person named Jiao Tietou 焦鉄頭, excavated in 1983 from a Tang-dynasty tomb west of Xi’an, was also encased in an armlet. A tube-shaped container with a lid was attached to the gilt-bronze armlet so that the amulet could be more conveniently placed inside (Li and Guan, 1984; Tsiang 2010, pp. 229-231). In 2000, another Tang-dynasty tomb west of Xi’an yielded a gilt-bronze armlet containing a heavily damaged amulet sheet. The armlet’s tube-shaped container was found to hold the fragments of the amulet sheet (Huo 1867, p. 88; Zhou 2000, p. 147; Tsiang 2010, p. 231).

Because armlets containing amulet sheets have only recently begun to receive scholarly attention, their locations in the tomb have rarely been noted in excavation reports. The silver armlet from a tomb found at the Sichuan University campus in Chengdu, however, was well documented, and the drawing of the tomb shows that the silver armband was worn on the upper right arm of the tomb occupant. A folded and rolled amulet printed by woodblock was found inside the silver armband (Feng 1957 pp. 48-51; Tsiang 2010, pp. 225-227; Copp, 2014, pp. 59, 77). The discovery of this tomb helps us understand how the amulet armband was actually used in the funerary context.

The popularity of this incantation’s mortuary function and bodily practice is partly explained by Buddhist scriptures. Several different versions of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment are found in the scriptures translated into Chinese between the seventh and eighth centuries.32 Representative scriptures include the aforementioned Baosiwei’s scripture,33 which is one of the earliest texts among dhāraṇī scriptures to encourage the making of material dhāraṇī (Copp, 2014, p. 67); the Scripture of the Great Wish-Fulfilling Incantation of the Great Invincible Luminous King of the Universally Radiant, Immaculate, Incandescent Wish-Granting Precious Seal Essence, translated by Amoghavajra (Bukong 不空, 705-774) (hereafter, Amoghavajra’s scripture);34 and the Ritual Manual of the Immediate Wish-Fulfilling Incantation for Accomplishment of Numinous Empowerment which is the Ultimate Secret Yoga of Adamantine-Crown of Attaining Buddhahood, also translated by Amoghavajra (hereafter, Amoghavajra’s ritual manual).

Both Baosiwei’s scripture and Amoghavajra’s scripture repeatedly state that one should wear a written Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment on one’s body, especially on the arm or neck.35 In these scriptures, the Buddha explains to Brahmā the various efficacies of the incantation and methods for activating the incantation’s power. At the beginning of his preaching, the Buddha says,

If one ably writes down and carries [the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment] on the neck or arm, the person will achieve all the meritorious deeds and obtain the most superb purity. This will make all the heavenly gods and the dragon kings always protect the person and make the Buddha and bodhisattvas remember him/her. Vajra Wielders, the Great Four Heavenly Kings . . . will, day and night, follow and protect the person who carries the incantation.36

若能書寫帶在頸者若在臂者 是人能成一切善事最勝清淨。常爲諸天龍王之所擁護 又爲諸佛菩薩之所憶念。金剛密跡四天大王 。。。晝夜而常隨逐擁護持此呪者。37

Following this passage, we encounter several episodes and instructions in the scriptures related to wearing the incantation on the body. For example, both scriptures narrate the stories of several figures: the king of Magadha who had his queen wear the amulet on her neck in hopes of conceiving a baby boy (T. 20, no. 1154: 641a; T. 20, no. 1153: 621c-622a); a sinner whose body was protected from all kinds of punishments by wearing the incantation amulet on his right arm (T. 20, no. 1154: 641b-c; T. 20, no. 1153: 623a-b);38 and a king named Fanshi 梵施 who defeated the invading troops through the spiritual power of an incantation amulet kept on his body (T. 20, no. 1154: 640b, T. 20,. no. 1153: 620c).

Although the scriptures do not directly mention an armlet when proscribing that a written incantation be worn on the arm, the meaning of the “armlet” (or necklace) was already implied in the title of the original Sanskrit version. The term

pratisarā, the keyword in the scripture’s Sanskrit title,

Mahāpratisarā dhāranī sūtra, is thought to have promoted the practice of using an armlet for wearing the incantation (Copp 2014, pp. 61-63). The basic meaning of the term

pratisarā is “a cord or ribbon used as an amulet worn round the neck or wrist at nuptials; a bracelet; a line returning into itself, circle; a form of magic or incantation; ornament, adorning” (Monier-Williams, 1899; Bhattacharya, 1900).

39 As for

dhāraṇī amulets worn on the body in the ancient Gandhara region, the charm boxes on the long necklaces that cross the chest of Gandharan bodhisattva images are thought to hold

dhāraṇī amulets. These charm boxes (i.e.,

pratisarā) on the bodhisattva statues probably reflect the contemporaneous

dhāraṇī practice of the royalty who wore similar adornments (Pal 2006) (

Figure 12).

The amulet armlets excavated from China show that Buddhist practitioners in medieval China not only wore them on the arm but also chose to be buried with such armlets. The reason for burying the armlet with the dead can also be found in the scriptures. Both Baosiwei’s and Amoghavajra’s scripture tell the story of a sinful monk who fell to hell but, thanks to the inscribed Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment placed on his body when buried, was soon reborn in the heavenly realm. The narrative is powerful and persuasive. According to the scriptures, the monk, due to his stealing of the monastic community’s property, fell to avīci, the deepest of the eight hells in the Buddhist cosmology; however, thanks to the incantation amulet on his body, the fires of hell were immediately extinguished and the prisoners of hell no longer felt pain. Surprised by this unusual phenomenon, Yama, the master of hell, dispatched his warden to the pagoda where the monk had been buried, who then reported to Yama that an amulet of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment had been placed on the monk’s body. With the power of the amulet that had been buried with his body, the monk soon was reborn in the Heaven of the Thirty-three Celestials (T. 20, no. 1154: 640c; T. 20, no. 1153: 621a-c). The amulets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment that have been excavated from tombs attest to the impact of this story in Tang China.

Unlike the great majority of containers in contemporaneous Chinese amulets, a gilt-bronze box, rather than an armlet, was used to hold the two amulet sheets from Mount Nam, Gyeongju. Are there cases in which Chinese amulets of

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment were discovered in similar metal boxes? Such cases are rare, but there are two notable examples. First, the aforementioned Madame Wei’s amulet came from a bronze box that entered the Yale University Art Gallery collection together with the amulet. The box is flat and round with a diameter of 4.13 cm. (

Figure 10 and

Figure 13) Although the bronze box is round rather than square, it shares commonalities with the Silla gilt-bronze box in that it is a lidded bronze container. Unfortunately, it is unknown whether this amulet container came from a tomb or a different context. The other notable case is the amulet excavated in 1975 from a Tang-dynasty tomb at the site of Xi’an Smelting Factory 西安冶金機械廠. This amulet came from a square bronze box; however, the bronze container was already badly corroded when excavated, and the restorers were unable to preserve it. The box measured 5 cm long by 6 cm wide (Tsiang 2010, pp. 236-237; Copp, 2014, p. 235). This is just a bit smaller than the Silla bronze box, which was 5.79 cm long by 8.63 cm wide. This informs us that sometimes the amulet was also placed in a bronze box when buried in a tomb in China.

Because the two amulets from Mount Nam are the only known cases of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment from Silla, it is harder to infer their context of placement on the mountain. Had they also been buried in a tomb, or enshrined in a totally different type of space? The only hint from which we can infer the original context of the amulets’ placement is that they were discovered on Mount Nam. Mount Nam was revered as a Buddha-land (foguotu 佛國土) realized on the territory of the Silla kingdom since Buddhism was transmitted to Silla in the early sixth century (Choe Minhui 2007). As a result, countless Buddhist statues and pagodas were erected and carved on this sacred mountain under the Silla kingdom.

If the gilt-bronze box holding the amulets came from this sacred mountain, it could have been enshrined in two different types of places. The first is the cinerary urns (

golho 骨壺) buried on Mount Nam. Although Mount Nam was a sacred Buddhist mountain—or because of it—some of Silla’s nobles chose to be buried on the mountain.

40 Archaeological excavations show that they were cremated following the Buddhist funerary method, and their ashes were placed in cinerary urns. Quite a few urns excavated from Mount Nam are now in the collection of the Gyeongju National Museum (Seok Byeongcheol 2007, p. 89) (

Figure 14).

41 Considering that Chinese amulets of

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment are often found in tombs, one might suggest that such burials of cinerary urns could have been the sites where the gilt-bronze case holding the amulets were found. Cinerary urns and their modest burial installations, however, rarely have burial goods for the dead. Thus, chances are low that the amulets came from cinerary urn burials.

The other possible enshrinement place of the “Silla amulets”42 is the relic crypts (sarigong 舍利孔) of the pagodas on Mount Nam. According to the research of Gyeongju Namsan Institute, the mountain still bears the remains of as many as 150 Buddhist temples and 99 pagodas (Gungnip Gyeongju Munhwajae Yeonguso 2002, p. 12). Unfortunately, most of the reliquaries and offerings enshrined in these pagodas’ relic crypts were lost during the Joseon dynasty’s persecution of Buddhism as well as the Colonial period when reliquaries were sought after as expensive “artworks” and cultural relics that could be sold on the market. For example, the three-story stone pagoda at the Yongjangsa 茸長寺 site on Mount Nam was plundered and destroyed in 1922. Although the pagoda was restored two years later, the whereabouts of the stolen reliquaries and the objects are still unknown.

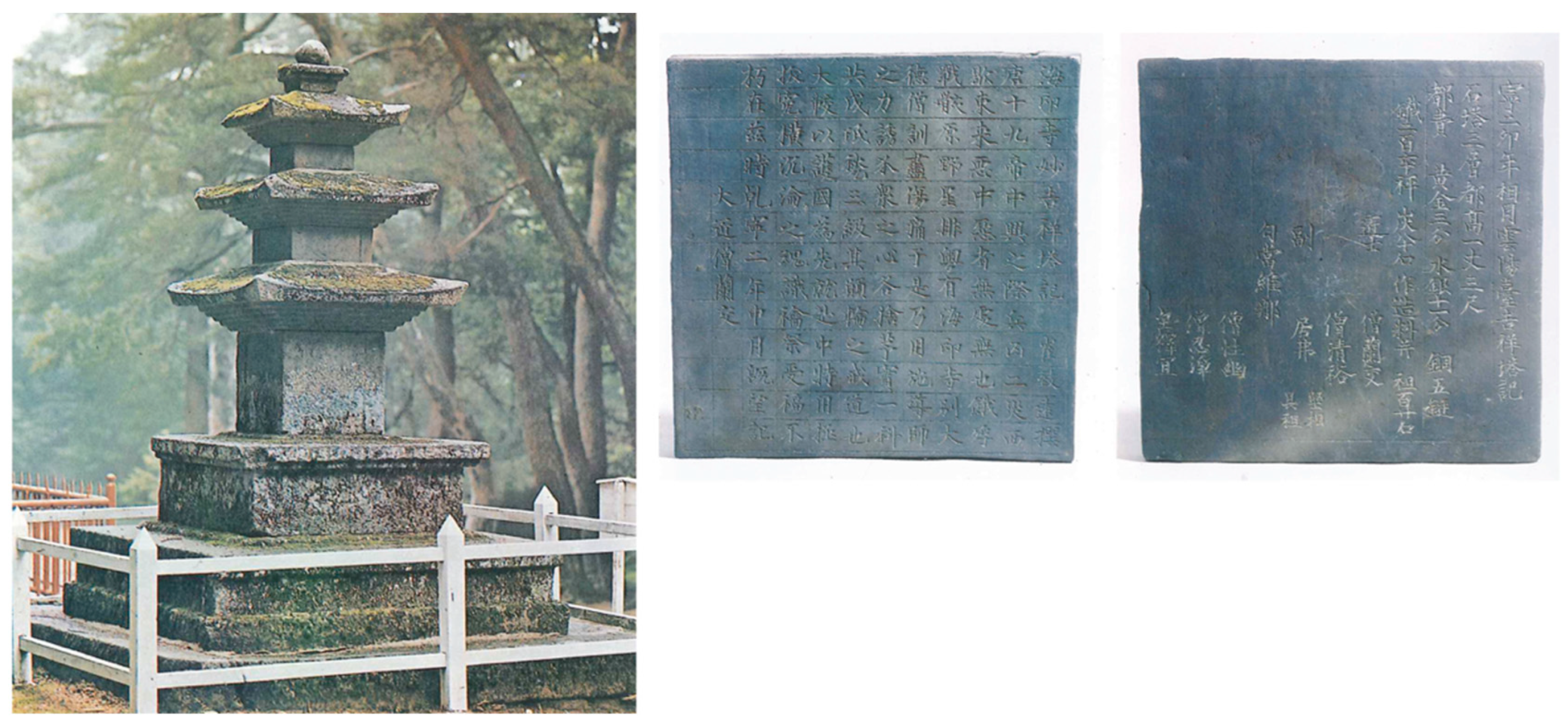

In this context, we should pay attention to an epigraph that shows the Silla kingdom indeed had a practice of enshrining the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in the pagoda’s relic crypt. In the 1960s, robbers plundered the relic crypt of Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa 海印寺妙吉祥塔. The objects stolen from the pagoda were retrieved in 1966. Among the retrieved objects were four panels of stone inscriptions dated to 895 that included the compositions of Choe Chiwon 崔致遠 (857–?), a famous writer and scholar of the Silla, and a monk named Sŭnghun 僧訓 (d.u.) (

Figure 15). What is relevant to our discussion is the inscription’s list of scriptures that were enshrined in the pagoda’s relic crypt. This list includes the

Pure Light Incantation Sūtra, the

Lotus Sūtra, the

Diamond Sūtra, and there is only one independent

dhāraṇī, which is none other than the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment (Ok Nayeong 2016b, pp. 183-185).

43 This epigraphic record from Silla clearly testifies that the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment was enshrined in the pagoda. It stands out because all the other texts enshrined in the pagoda were scriptures rather than independent incantations. Why was this incantation specifically chosen to be enshrined in this pagoda? Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa was a monument built for the posthumous blessing of the dozens of monk soldiers and laypeople who died in a local battle. The stone panel was also inscribed with the names of those who died in the battle, and Choe Chiwon’s description of the devastating war and consolation for the dead (Youn-mi Kim 2019, pp. 198-199). Considering the mortuary function of the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment, which was believed to have efficacy to save the dead from hell and guarantee rebirth in the heavenly realm, we can infer that the incantation was placed in the pagoda to wish for a good afterlife for the monk soldiers who died in the battle (Ok Nayeong 2016b, pp. 183-185). Buddhologists often assume that

dhāraṇīs and scriptures enshrined in a pagoda were simply used as textual relics (

fasheli 法舍利), but this case shows that the

Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment was placed in the pagoda for its mortuary function. This conforms to the recent observation that Korean and Chinese pagodas were often erected to make

zhuifu 追福 (offering blessings to the deceased) for the patron’s kin and community members by transferring the merit of building the pagoda to the dead (Youn-mi Kim 2019).

Considering that the Silla kingdom has a practice of enshrining the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in a pagoda, we can infer that the two amulets from Mount Nam came from one of the numerous pagodas built on this mountain during the Silla. It is also notable that Silla amulets entered the Museum of the Government-General of Korea collection during the colonial period because objects plundered from pagodas and tombs were often purchased by museums and collectors during that time.

One of the scriptural bases for placing the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in the pagoda may have been the aforementioned story of the sinful monk who was saved from hell by the amulet’s efficacy. According to both Baosiwei’s and Amoghavajra’s scripture, the body of the sinful monk, on which the amulet was placed, was not buried in a normal tomb but in a pagoda (T. 20, no, 1154: 640c; T. 20, no. 1153: 621a-c). In addition, Amoghavajra’s scripture includes instructions to write the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment on a palm leaf, wrap it with colorful silk of superb quality, and enshrine it in a pagoda (應以殊勝繒綵纒裹經夾安於塔中, T. 20, no. 1153: 621c15-16). Doing so, the scripture says, makes all of the wishes fulfilled (T. 20, no. 1153: 621c). Although the scriptural injunction is usually not the only shaping factor of religious practice, it can definitely serve as one. The mention of pagodas as the place for enshrining the written Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in the scriptures could have been one factor behind the Silla’s practice of enshrining the incantation in a pagoda.

As for China, the earliest, and the only, case of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets enshrined in a pagoda comes from the Song dynasty (960–1276). The excavation in 1978 of the pagoda at Ruiguangsi 瑞光寺in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, revealed two sets of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet prints, one in Chinese (1001 CE) and the other in Indic script (1005 CE). The amulets were found sealed in the central pillar of the reliquary that emulated the shape of the universe in Buddhist cosmology (Ma 2004, p. 575; Wang 2011).44 Although future excavations might find more cases, the Ruiguangsi pagoda is the only Chinese pagoda known to have yielded the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets in its relic crypt.

Considering that Silla was the dynasty that began the practice of enshrining the Pure Light Incantation in pagodas, long before that practice spread in China, it is possible that Silla Buddhists also began enshrining the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment in pagodas earlier than Chinese Buddhists. The Sūtra of the Pure Light Incantation and miniature pagodas based on this scripture were often placed in Silla pagodas since the eighth century (Ju Gyeongmi 2004). On the other hand, it was only in the eleventh century under the Liao dynasty (916–1125) that it became widespread in China, which suggests its connection to the previous Korean culture of enshrining scriptures, especially the Sūtra of the Pure Light Incantation, in pagodas (Shen 2001, p. 295).

The Incantation, the Dragon, and the Heavenly Kings in the Silla Culture

As examined above, the newly rediscovered amulets, and Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa’s epistemological record prove that Silla also had material dhāraṇī practices pertaining to the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. Ok Nayoung recently suggested that the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment was probably transmitted to Silla due to the increased cultural and political exchanges between the Unified Silla and the Tang during the reign of Emperor Daizong 代宗 (r. 762–779) (Ok Nayeong 2016b, p. 182). Considering the usage of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment by famed monks active in Tang, including Vajrabodhi (金剛智, 671–741), Amoghavajra, Huiguo 惠果 (746–805), Fazang 法藏 (643–712), as well as Emperor Suzong 肅宗 (756–762) (Huang 2006), it is plausible that the incantation came to be known to the elite circle of the Unified Silla.

At the same time, the scriptures of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment offer further hints about why this Buddhist incantation gained popularity in the Silla kingdom. In the scriptures, dragons and the four heavenly kings appear multiple times, both of which were important in Silla’s religious landscape. The beginning section of Baosiwei’s scripture explains that the dragon kings and the four heavenly kings will protect the person who keeps the written Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment on their neck or arm (T. 20, no. 1154: 637c).45 Similar contents also appear in the verse in Amoghavajra’s scripture (T. 20, no. 1153: 617c). In addition, the scriptures mention how the incantation can appease the rage of the dragon kings, turn the dragon kings into compassionate beings, and have them make rain when necessary. The dragons and dragon kings were particularly important in Silla’s religious cosmology. The myths from Silla are replete with dragons, such as the golden dragon that appeared at the site where the Yellow Dragon Monastery was later built,46 and King Munmu 文武 (r. 661–681), who was believed to have been reincarnated as the dragon king for the protection of his kingdom (Youn-mi Kim 2019). In Silla, where the prior worship of dragons was subsumed into the Buddhism tradition, the incantation’s relationship with the dragon probably made the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment more appealing to Silla Buddhist practitioners.

The four heavenly kings, whose protection of the amulet bearers was promised by the scriptures, were tremendously important deities in Silla Buddhism because they were believed to be the protectors of the Silla kingdom. Due to the widespread worship of the four heavenly kings, their images were frequently represented on Silla pagodas, especially those built at the monastery associated with the state protection, and their reliquaries since the seventh century.47 In China, the scriptures’ emphasis on the four heavenly kings was reflected in the later designs of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets, such as the amulet from 1001 excavated from the Ruiguangsi pagoda. The scriptures' promise of the four heavenly kings’ protection may have been one more factor behind the Silla’s acceptance of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment practice.

Figure 1.

Dry-plate photographs from the colonial period (1910-45), catalog no. 건판034991. National Museum of Korea.

Figure 1.

Dry-plate photographs from the colonial period (1910-45), catalog no. 건판034991. National Museum of Korea.

Figure 2.

Illustration in Kushi, Zusetsu Chōsen bijutsu, p.109.

Figure 2.

Illustration in Kushi, Zusetsu Chōsen bijutsu, p.109.

Figure 3.

Gilt-bronze box. 5.79 cm × 8.63 cm × 3.55 cm. Silla period, Korea. National Museum of Korea [KOGL Korea Open Government License type 1. Image downloaded from e-Museum in Feb, 2023].

Figure 3.

Gilt-bronze box. 5.79 cm × 8.63 cm × 3.55 cm. Silla period, Korea. National Museum of Korea [KOGL Korea Open Government License type 1. Image downloaded from e-Museum in Feb, 2023].

Figure 4.

Left) Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam, Gyeongju, Korea. Ink and color on paper. Ca. 31.3 cm × 44 cm. National Museum of Korea; (Right) Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Chinese script from Mount Nam, Gyeong.

Figure 4.

Left) Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam, Gyeongju, Korea. Ink and color on paper. Ca. 31.3 cm × 44 cm. National Museum of Korea; (Right) Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Chinese script from Mount Nam, Gyeong.

Figure 5.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam. National Museum of Korea [Modified from Han Joung Ho’s photograph].

Figure 5.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam. National Museum of Korea [Modified from Han Joung Ho’s photograph].

Figure 6.

Jing Sitai’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script, excavate at Fengxi 灃西, Xi’an. Printed and hand drawn on paper. Ca. 32.3 cm × 28.1 cm. Eighth century, Tang period, China [Image modified from the plate in An and Feng, “Xi’an Fengxi chutu de Tang yinben fanwen tuoluoni jingzhou.”].

Figure 6.

Jing Sitai’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script, excavate at Fengxi 灃西, Xi’an. Printed and hand drawn on paper. Ca. 32.3 cm × 28.1 cm. Eighth century, Tang period, China [Image modified from the plate in An and Feng, “Xi’an Fengxi chutu de Tang yinben fanwen tuoluoni jingzhou.”].

Figure 7.

Gilt-bronze reliquary box excavated from the three-story stone pagoda at Bulguksa. 6.8 cm × 7 cm. Late eighth - early ninth century, Silla period, Korea [© Cultural Heritage Administration].

Figure 7.

Gilt-bronze reliquary box excavated from the three-story stone pagoda at Bulguksa. 6.8 cm × 7 cm. Late eighth - early ninth century, Silla period, Korea [© Cultural Heritage Administration].

Figure 8.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in the Chinese script from Mount Nam.

Figure 8.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in the Chinese script from Mount Nam.

Figure 9.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in the Chinese script from Mount Nam.

Figure 9.

Detail of the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in the Chinese script from Mount Nam.

Figure 10.

Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script. Handwritten printed and painted on silk. 21.5 cm × 21.5 cm. Eighth century, Tang period, China. Yale University of Art Gallery. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 10.

Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script. Handwritten printed and painted on silk. 21.5 cm × 21.5 cm. Eighth century, Tang period, China. Yale University of Art Gallery. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 11.

(Above)Letters in Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet; (below) letters in the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam.

Figure 11.

(Above)Letters in Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet; (below) letters in the Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulet in Indic Script from Mount Nam.

Figure 12.

Standing Bodisattva Maitreya from Gandhara. Schist. Ca. 3rd century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 12.

Standing Bodisattva Maitreya from Gandhara. Schist. Ca. 3rd century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 13.

Bronze case of the Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. Tang period, China. Yale University of Art Gallery. Yale University of Art Gallery. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 13.

Bronze case of the Madam Wei’s Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment. Tang period, China. Yale University of Art Gallery. Yale University of Art Gallery. Image in Public Domain.

Figure 14.

Cinerary urn with a hand and a lid, found in the Mount Nam area. Height 19.4 cm. Seventh - Eighth century, Silla period, Korea. Gyeongju National Museum [Gungnip Gyeongju Munhwajae Yeonguso, Gyeongju Namsan, p. 367].

Figure 14.

Cinerary urn with a hand and a lid, found in the Mount Nam area. Height 19.4 cm. Seventh - Eighth century, Silla period, Korea. Gyeongju National Museum [Gungnip Gyeongju Munhwajae Yeonguso, Gyeongju Namsan, p. 367].

Figure 15.

Record of Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa engraved on stone penal, excavated from the relic crypt of Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa, South Kyŏngsang Province. Each stone panel 23 cm x 23 cm. 895, Silla period, Korea. National Museum of Korea. [Gungnip jungang bangmulgwan, Bulsari jangeom].

Figure 15.

Record of Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa engraved on stone penal, excavated from the relic crypt of Myogilsang Pagoda at Haeinsa, South Kyŏngsang Province. Each stone panel 23 cm x 23 cm. 895, Silla period, Korea. National Museum of Korea. [Gungnip jungang bangmulgwan, Bulsari jangeom].

Table 1.

Characteristics of earlier and later Chinese Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets from the mid 8th to early 11th century.

Table 1.

Characteristics of earlier and later Chinese Incantation of Wish-Fulfillment amulets from the mid 8th to early 11th century.

| |

Amulets in the Early Stage |

Amulets in the Late Stage |

| Central Deity |

Vajra bodhisattva

or vajra warrior |

Bodhisattva of Wish Fulfillment

or Vairocana Buddha |

| Shape |

Square |

Circle |

| Production Method |

Handwritten and hand-drawn |

Woodblock printed or stamped |

| Complexity of Design |

Simpler |

More complicated |

| Donor’s Name |

Inscribed in an empty space |

Included in the printed prayer text |