1. Introduction

Innovativeness is one of the main components of the entrepreneurial and strategic orientation of a company (Gomes, Seman, Berndt, & Bogoni, 2022). It refers to the receptivity and inclination of an organisation to adopt new ideas that lead to the development and launch of new products and services in order to increase customer satisfaction, as well as to create a competitive advantage for the company (Rubera & Kirca, 2012). Innovation is the measure of an organisation's propensity to innovate (Salavou, 2004).

From a strategic perspective as recognised, firm performance is a function of the internal capabilities of the firm but also the behaviour of the external environment, such as the environmental dynamism in which the firm operates (Fu, et al., 2021). For example, it is widely recognised that political stability, constantly changing market supply and demand, unpredictable competitor behaviour, technological change, etc. have a significant effect on the impact of the firm's internal capabilities on its performance.

Since the 1980s, developing countries have adopted policies to improve the efficiency of their markets. Led by institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, these reforms aimed, among other things, to harmonise the business climate and develop competitiveness to improve the efficiency of domestic firms. However, in some countries such as the DRC, these structural reforms and business climate harmonisation appear to have had limited effect or negative effect on firm performance (Saul & Adeline, 2018).

Nevertheless, as Davis et al. (2010) point out, there has been little research on how strategic orientation would influence the performance of firms competing in a competitive and changing economic environment. Thus, there is a need to study how the dynamism of the business environment affects the links between innovative capability and firm performance in developing countries. Indeed, this study explicitly examines this relationship among manufacturing firms operating in the north-eastern part of the DRC. These companies face a strong wave of imports of the same locally manufactured products, thus compromising the competitiveness of Congolese products.

This study contributes to the literature on strategic orientation and the behaviour of the firm's external environment in order to enrich the theory of strategic orientation of manufacturing firms in the DRC in particular. This study empirically examines the adoption of innovation as an integral component of entrepreneurial orientation by MSMEs in the north-eastern region of the DRC comprising the provinces of Ituri and Nord Kivu. This contribution provides information and insight to stakeholders in the Congolese manufacturing industry, including policy makers and managers of these firms, to improve the performance of manufacturing MSMEs by improving the environment in which these firms operate.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Innovativeness

Innovativeness (INN) is one of the key components of company strategic orientation (Hernández-Perlines, Cisneros, Ribeiro-Soriano, & Mogorrón-Guerrero, 2020). It is the propensity of companies to come up with newness in their products and services (Nair, Guldiken, Fainshmidt, & Pezeshkan, 2015). INN demonstrates the tendency of being creative and constantly testing new ideas, in order to bring to the market new products, new services, new production methods or finding new market (Covin & Wales, 2012), in order to improve the consumer’s well-being and the company’s survival (Meissner & Kotsemir, 2016, p. 1).

The notion of innovation in entrepreneurship was popularised by Joseph Schumpeter (Singh & Hanafi, 2020). Schumpeter (1934) defined innovation as the “creative destruction” mechanism companies use to create wealth by converting resources. This resources conversion can lead to the creation of new products, new processes or new technological innovations (Alharbi, Jamil, Mahmood, & Shaharoun, 2019). According to Vyas (2009), such INN is exhibited within companies in five ways namely (1) creation of new products or qualitative improvements in existing products, (2) use of a new industrial process, (3) new market openings, (4) development of new raw-material sources or other new inputs and (5) new forms of industrial organisations.

Product and service innovation is the creation of different new products and services through upgrading the quality of current products and services in order to improve customer experience, and customer satisfaction as well (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Singh & Hanafi, 2020). INN in technology is the fact of companies’ orientation towards embracing new working techniques, processes, tools and skills (Covin & Wales, 2012; Lechner & Gudmundsson, 2014; Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, & Frese, 2009). This leads to competitive advantage improvement, since it enhances products’ quality and the nature of the services delivered to the consumers (Garvin, 1987; Singh & Hanafi, 2020). Innovation is also exhibited through the new market creation (Wan & Lee, 2005; Singh & Hanafi, 2020). This means that an innovative company is the one that searches for new markets, new clients for their products and services. They design new products and services that attracts more new clients. This leads to the increase of their market shares with subsequent consequences on their performance.

The literature recognises the presence of several barriers such as weak enabling factors, lack of innovation leadership at all levels within the company, limited knowledge of innovation processes and methods, etc. as factors that hinder INN with companies (Bocken & Geradts, 2020). Consequently, businesses that need to gain more performance have the burden of overcoming those barriers that hinder their innovation capabilities.

Innovative companies are also firms that back and encourage their employees to create new ideas, bring in new changes in their ways of designing products, services and processes (Khaleel, Al-shami, Majid, & Adel, 2017). Innovative companies favour a strong emphasis on R&D, technology leadership and innovation in the industry. That is why, as confirmed by previous studies (Atalaya & Sarvan, 2013; Chen, et al., 2022; Zand & Rezaei, 2020), innovation does positively impact on the business performance.

Innovativeness is, therefore, a strategic tool that companies operating in a competitive environment rely on in order to improve their performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formulated:

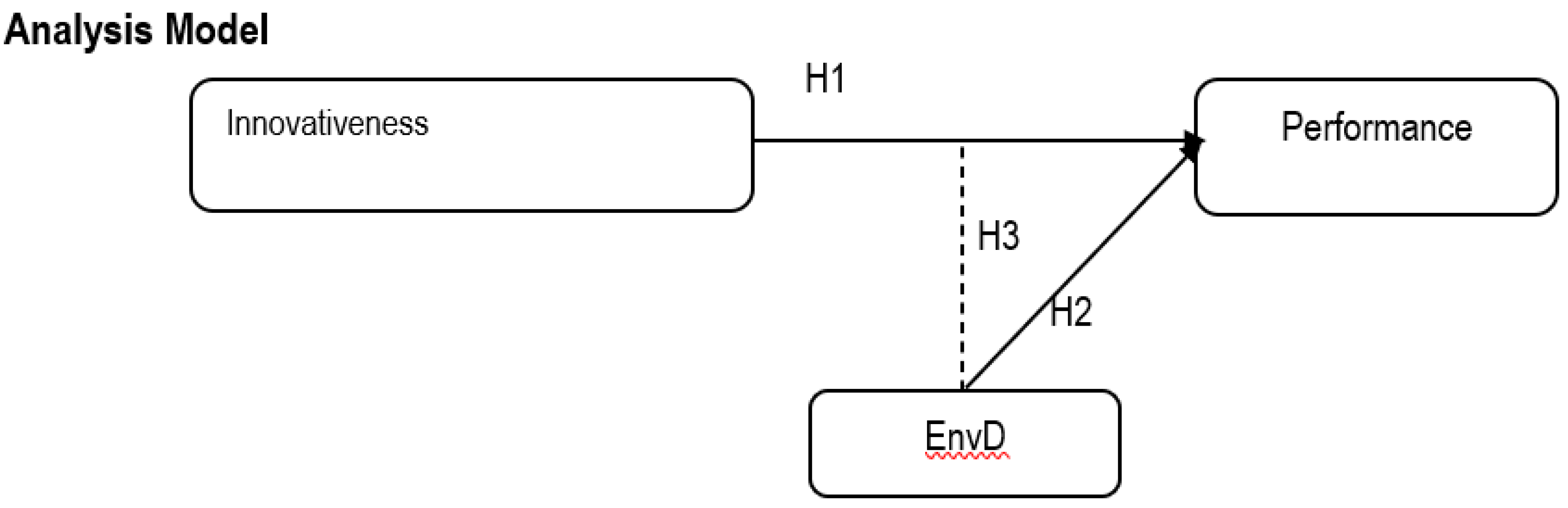

H1.

Innovativeness has a positive significant effect on company performance.

Environment Dynamism

Environmental dynamism (ED) is the extent of unpredictable and instable variations in a business environment. Such unpredictability is usually constant in the business environment (Goll & Rasheed, 2004, p. 44). ED is the level of uncertainty or volatility observed in a business environment. According to the literature (Feyen, Frost, Gambacorta, Natarajan, & Saal, 2021; Gazzola, Pavione, Pezzetti, & Grechi, 2020; Thai, 2015) there are different factors that act as sources of environment dynamism such as the level of shifts in technology adoption in an industry, advent of advanced technologies, the changes in culture and consumers’ tastes, economic factors, the actions of competitors, political and security stability, government policy, etc. These factors can make the environment of an industry unstable and make predictions difficult to make in a given industry.

Economic Factors

Economic factors are fundamentals that derive from the business environment and that affect businesses or investments’ value. These dynamics can be the size of the economy, the country risk, labour costs, and openness to international trade, etc. (Janicki & Wunnava, 2004). These economic factors are grouped into two broad sets namely microeconomic and macroeconomic factors. Macroeconomic factors are broad economic factors that affect the entire economy and all of its participants. These are the fluctuations in the country’s GDP. A high and constant rate GDP reflects the country’s economy performance. It insures companies about the future demand, since the GDP per capita reflects the population living standards, their purchasing power, as well it determines the country attractiveness (Liu, Tang, Chen, & Poznanska, 2017; Shah, Kamal, Hasnat,, & Jiang, 2019). The ED is also influenced by inflation and unemployment rates. These two economic indicators act as external factors to impact the company’s strategic effort towards performance.

Government Policies

The economic dynamism results also from the variations in the government policies towards business environment. These changes can be the variations in government fiscal policy directed to favour or not companies’ competitiveness and performance. Such changes can also result from the instabilities perceived in the country’s economy. Hence, when there is country’s economy experiencing up and down economy unsteadiness, surge in prices, currency depreciation, etc., this can push companies to change the way they operate. In such business environments it turns out to be difficult in predicting even the immediate future of the economy developments.

Arrival and Exit of Companies from the Industry

The ED is also observed by the arrival and exit of new competitors in the industry. This movement of firms into and out of an industry is due to the fact that, in an unstable environment, firms are unlikely to survive due to multiple factors that change dramatically, often to the detriment of the firm. Thus, companies that start or enter the industry eventually leave it because they are not able to withstand it due to either competition, lack of environmental munificence, or the deterioration of working conditions in such an environment.

Constant Technological Changes and Adoption

The constant technological changes and their adoption by firms further affects the business environment (Ting, Wang, & Wang, 2012, p. 518). Adeoye (2013) understands technology as the use of scientific principles and mechanical arts in the performance of various tasks in a business. However, in this era, the rate of technological change is very high, but also access to the best technologies is costly for firms with such a high rate of attrition, so it becomes difficult for firms to adapt to it, especially small and low-income ones. The use of technology builds the competitive advantage of those firms that adopt it. Firms that are able to adopt new technologies are more likely to be offered a competitive advantage than their competitors (Blichfeldt & Faullant, 2021). New technologies have the capacity to reduce production costs, improve output quality and achieve economies of scale and facilitate communication and access to customers. Hence its place in building competitive advantage.

Political and Security Stability

The dynamism of the business environment is also observed through political and security stability. This refers to changes in political events such as insecurity and conflict, the adoption or rejection of laws and rules by a regime, or simply when government policies are not stable enough to maintain a stable business environment, this can lead to market instability and discourage investment. In addition to political stability, law and order and the quality of administrative processes may also significantly impact countries’ business environment, as well as the firms’ productivity (Volberda, Van der Weerdt, Verwaal, Stienstra, & Verdu, 2012). Taking the context of the DRC, particularly in the eastern part of the country, the business environment is highly unstable due to the high level of insecurity maintained by a multitude of armed groups and the inability of the Congolese state to eradicate them. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H2. Environmental dynamism has a negative significant effect on company performance.

Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism

Dynamic business environment plays a role vital role in influencing the effect of INN undertaken by organisations in enhancing company performance (Tajeddini, Martin, & Ali, 2020; Tajeddini & Mueller, 2018). From a contingency perspective, the dynamism and stability of the business environment are decisive elements that determining the company performance. For instance, Chemma (2021) and Lumpkin and Dess (2001) reported that competitive dynamics exert pressure and constrain companies to be innovative in order to survive and grow. It means, in a highly changing and unpredictable environment, the best way for companies to survive, is to develop a strong entrepreneurial posture, especially innovativeness.

Kraus et al. (2012) reported that innovative companies do perform better in turbulent environments. Thus uncertain business environment acts as a catalyst that pushes companies to engage more in innovation. Such INN leads them to gain competitive advantage by offering goods and services that are adapted to customer’s need and expectation (Palazzeschi, Bucci, & Di Fabio, 2018, p. 1). Hence, through innovations companies are able to produce and sell goods that meet consumer expectations. As they will continue to innovate out of fear of environmental uncertainty, companies build better position to expand their market by gaining more market share, selling more and consistently satisfying their customers. Therefore, the environmental uncertainty manifested through ED plays a crucial role in the development of innovation, in consequence it leads to the sustainable achievement of the company's performance.

A dynamic environment given its uncertainties, it forces companies working in such a context to make greater efforts to balance the discrepancy brought about by an unstable environment (Prajogo, 2016; Zehir & Balak, 2018). However, it is still advisable to minimise the level of risk to be taken by avoiding overly risky projects with unlikely economies.

However, some scholars have reported opposed conclusions. For instance, Agyapong et al. (2021) and Taghizadeh et al. (2021) stated that an over changing business environment does weaken the effect of product innovation on business performance. Which means that in a highly dynamic business environment, taking too much innovation initiatives may lead to counterproductive company performance.

Hence, it should be recognised that the business environment of in the north-eastern DRC as in the entire country is highly instable and seems to create more constraints than new opportunities to companies; which though are called upon to respond creatively and innovatively (Shah, Shah, & El-Gohary, 2022), are experiencing tough working conditions. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H3. Environmental dynamism has a negative significant effect in the relationship between innovativeness and company performance.

Figure 1.

Analysis Model.

Figure 1.

Analysis Model.

3. Methodology

The survey questionnaire was distributed to 344 owner-managers of Congolese micro, small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises operating in north-eastern DRC. Respondents included owners, senior managers including CEOs, production managers, marketing managers, finance managers and others with these responsibilities. These respondents constituted the target group for our study, given their knowledge of the subject matter and their experience in their companies. Of the 344 questionnaires issued, only 178 were returned and were usable for the analyses, i.e. a response rate of 51.7%, which is adequate as it is recognised in the literature that surveying executives leads usually to a low response rate of around 30% (Cycyota and Harrison, 2006; Baruch and Holtom, 2008). A response rate of above 30% minimises the non-response bias risk in a survey (Geyer et al., 2020).

The research location for this study is the north-eastern region of the DRC, consisting of the provinces of Ituri and North Kivu. The study units of analysis, i.e. the whole units that are being studied (Kumar, 2018), are the manufacturing companies operating in the North-eastern DRC, whereas the study units of observation, meaning the individuals from whom the data are collected, are the owner-managers of those manufacturing enterprises operating in the region. The study used multiple respondents per company in order to reduce the risk of bias due to the consideration of a single perspective. This approach provided much more precision in respondents’ answers. It avoids biases linked to the use of single respondent’s desired perspective (Ried, Eckerd, & Kaufmann, 2022, p. 5). Self-reported items by a single respondent may be affected by bias (Kreitchmann, Abad, Ponsoda, Nieto, & Morillo, 2019, p. 2).

The data collected was analysed using SPSS 25 to test the study hypotheses. The questionnaire used for data collection was adapted from previous work by the authors (e.g. Covin and Slevin,1989; Lumpkin and Dess, 2001, Miller and Friesen, 1982) which addressed the same variables considered in the present study. The questionnaire was constructed using a 5 level Likert scale where 1 = "strongly disagree" to 5 = "strongly agree".

To ensure the quality of the research tool, the reliability of the internal consistency of the scale was checked through Cronbach's alpha. This has guaranteed that the same latent trait on the same scale is being measured (Taber, 2018). The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the three constructs ranged from .712 to .862 (innovativeness .808, environmental dynamism .712, company performance .862) which confirms that the questionnaire was sufficiently (Ponterotto & Ruckdeschel, 2007; Crutzen & Peters, 2017). The study’s detailed results are depicted in the following paragraphs.

4. Results

Descriptive Statistics

In regard to data analysis the study made recourse to the ordinary least square regression approach and descriptive statistics to answer the study questions. 9.6% of the respondents were owners of the surveyed companies, the remaining 84% were managers or equivalent. Only 1.7% among the respondents have the Master’s degree as the highest educational qualification. 78.7% among the respondents were males and 21.3% females.

The results testing the relation between innovativeness and firm performance and the moderating effect of environmental dynamism in innovativeness-firm performance relationship are summarised in the

Table 1 In two models.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis

Model 1 in

Table 1 depicts the results of the multiple regression analysis that examines the main effect of INN on company performance. It includes the moderating factor (ED) and the control variables. As predicted, INN has positive and significant effect on company performance (

β =.283; p<.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. The moderating factor, ED has positive but weakly significant (

β = .128; p= .077) effect on manufacturing company performance. Thus the study Hypothesis 2 is rejected; ED exhibits a positive effect on company performance. In relation to the control variables of the Model 1, firm location has a positive and significant effect (

β =.571; p<.001) on performance, while firm age has a negative and significant effect (

β = -.020; p<.001) on performance and firm size shows no relationship with company performance.

Model 2 shows the INN having a significantly positive effect on company performance (β =.263; p= .001). The interaction term INN*ED has a negative but weakly significant effect (β = -.151; p=.068)) on company performance, thus supporting Hypothesis 3, suggesting that ED has a negative effect in INN-company performance relationship. Regarding the control variables of the Model 1, firm location (β= .542; p<.001) was positively related to performance, while firm age (β= -.021; p< .001) was negatively related to performance and firm size did not have relationship with performance.

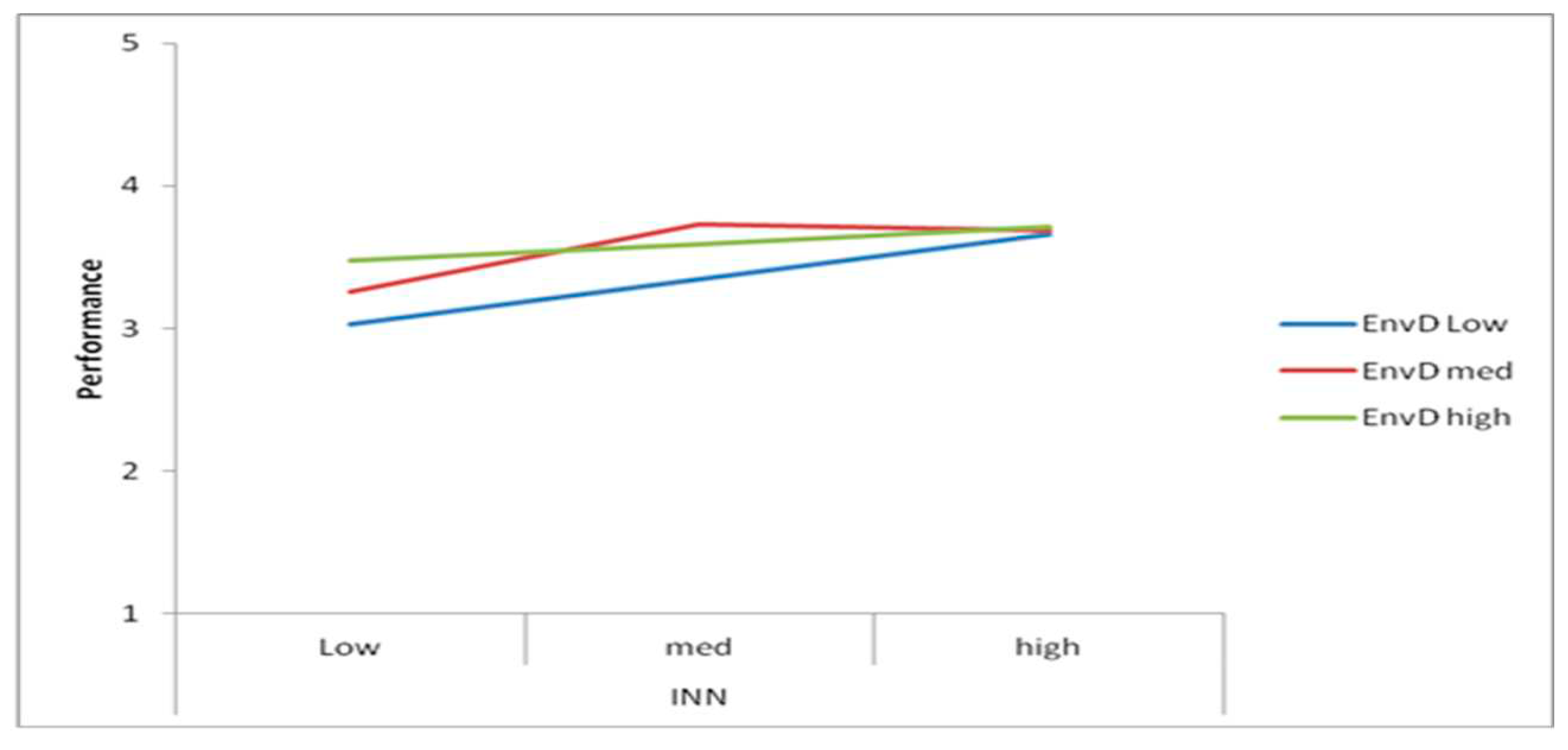

From the

Figure 2 it is observed that lowly innovative companies have the highest level of their performance when the environmental dynamism is high. However, moderately innovative companies have the best level of performance when the dynamism of the environment is medium; nevertheless, when a company is a highly innovative the business environmental dynamism does not affect its performance at all.

5. Discussions and Implications

The literature (Chemma, 2021; Ramdani, Binsaif, & Boukarmi, 2019) devotes a lot of attention to innovation as an inescapable mechanism in the competition because it can be used as a tool to disrupt competitors and chase their products from the market. But also companies use it to survive and grow. The present result is in line with this same perspective admitting the positive contribution of innovation on the performance of companies (Canh, Liem, Thu, & Khuong, 2019). This is further in line with the findings of Fu et al. (2021) who reported a significant association between innovation and company performance.

However, previous studies have neglected the link between innovation and the instability of the business environment and company performance. This has led to little light shed on the overall effect of the intensity of unstable business environment on the relationship between innovation and company performance. In order to contribute to the understanding of this phenomenon, the present study was interested in analysing the moderating effect of environmental dynamism in the innovation-performance relationship of companies.

The result of the study showed a negative moderating effect of ED in the INN- company performance relationship. These findings are in line with previous studies such as Agyapong et al. (2021) and Taghizadeh et al. (2021) who reported negative interaction between innovation and (market) ED on firm performance. However, this result is in contrast with other studies such as Rodriguez-Pena (2021) and Fadlilah et al. (2021) who have found significant positive effect of environmental dynamism in the innovation-performance relationship.

These research findings suggest that in the context of high market uncertainties characterised by unpredictable competitors’ behaviour, the struggle for market share, change and adoption of new technologies can have perverse negative effects on innovation, thereby destroying company performance. However, as depicted in the

Figure 2 this environmental pressure does only influence the performance of low and medium innovative companies, with no effect of highly innovative ones. This results states that by trying to adapt to the competition pressure, companies can end up making wrong decisions, for example investing a lot of money in marketing, in the acquisition of new knowledge and technologies, which in the short term can generate more perverse results for the company, mostly for less and medium innovative companies.

The uncertainty of the environment can also result from constraints created by the government itself by imposing regulations and or abandoning the industry in administrative chaos, or simply by the inability to secure the business environment from diverse factors which can compromise it (UNIDO and GTZ, 2008), as experienced in the DRC context. The lack of government assurance undermines confidence in the business environment.

Incentive intervention by the government can create a significant leverage effect for businesses. Tax facilities, simplification of business administrative procedures, law enforcement and order, as well as the availability of production infrastructure would encourage innovation within companies and lead to significant effect on company performance. However, when governments cease or act laxly in carrying out these tasks, a hostile business environment arises that discourages internal entrepreneurial posture within companies, with destructive consequences for companies’ performance and competitiveness. In other words, in an uncertain economic environment that is bathed in widespread instability, as is the case in the DRC, innovation will tend to have little or no effect on the company.

Although business environment challenges serve as an incentive for enterprises to deploy more resources and adaptation strategies to survive, the excess of such a high level of instability in the economic environment can be harmful. It may condemn companies operating in such context to perish or leave the industry. The challenges, the exciting constraints should not be more than the opportunities and resources that the environment offers. Otherwise, the business environment becomes suffocating for the companies and opens the door to their exit from the market.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

Manufacturing companies play significant role in DRC economy through employment and economy growth. The managerial effort in terms of innovativeness has significant influence on their performance. However, the poor supporting business environment characterised by high level of uncertainties and instability where they operate creates damaging effects on their performance as it weakens the innovation efforts deployed by their management teams. To better escape from the business environment instability pervasiveness, companies need to adapt their level and strategies for innovation to the nature of their business environment. Otherwise their performance will drop as the business environment remains unsteady.

This study raises limitations that should be of interest for further research. First, the results of this study are based on subjective measures obtained from the opinions of the owner-managers of the manufacturing companies in DRC’s north-eastern region. Further studies can be carried out using objective measures available as captured in the financial statements of those companies. Secondly, having used a cross-sectional approach to data collection from companies, this study fails to capture the effect of strategic changes related to temporary change in companies of the region. Cross-sectional studies can help to understand how, over time, environmental dynamism influences the relationship between innovation and performance of these companies. On the other hand, the data considered in this study only concerned the north-eastern part of the DRC, future studies may look at other regions or the whole country. Nevertheless, the present research offers a starting point for further studies on innovation under uncertainty to further illuminate the decisions of managers of manufacturing companies operating under high uncertainty.

References

- Adeoye, M. O. (2013). The impact of business environement on entrepreneurship performace in Nigeria. Computing, Information Systems, Development Informatics & Allied Research, 4 (4 ), 59-64.

- Agyapong, A., Mensah, H., & Akomea, S. (2021). Innovation-performance relationship: The moderating role of market dynamism. Small Enterprise Research, 28(3), 350-372. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, I., Jamil, R., Mahmood, N., & Shaharoun, A. (2019). Organizational innovation: A rReview paper. Open Journal of Business and Management, 7(1), 1196-1206. [CrossRef]

- Atalaya, M., & Sarvan, F. (2013). The relationship between innovation and firm performance: An empirical evidence from Turkish automotive supplier industry. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 75, 226-235. [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y., & Holtom, B. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), 1139-1160. [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, H., & Faullant, R. (2021). Performance effects of digital technology adoption and product & service innovation – A process-industry perspective. Technovation, 105, 102275. [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N., & Geradts, T. (2020). arriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 53(4), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Canh, N., Liem, N., Thu, P., & Khuong, N. (2019). The impact of innovation on the firm performance and corporate social responsibility of Vietnamese manufacturing firms. Sustainability, 11(13), 3666. [CrossRef]

- Chemma, N. (2021). Disruptive innovation in a dynamic environment: a winning strategy? An illustration through the analysis of the yoghurt industry in Algeria. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(34), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Shu, W., Wang, X., Sial, M., Sehleanu, M., & Badulescu, D. (2022). The impact of environmental uncertainty on corporate innovation: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(1), 334. [CrossRef]

- Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The Measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory& Practice, 677-702. [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, R., & Peters, G.-J. (2017). Scale quality: alpha is an inadequate estimate and factor-analytic evidence is needed first of all. Health Psychology Review, 11(3), 242-247. [CrossRef]

- Cycyota, C., & Harrison, D. (2006). What (not) to expect when surveying executives. A meta‐analysis of top manager response rates and techniques over time. Organizational Research Methods, 9 (2), 133-160. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J., Bell, G., Payne, G., & Kreiser, P. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The moderating role of managerial power. American Journal of Business, 25(2), 41-54. [CrossRef]

- Fadlilah, A., Ramadhany, A., Nabella, S., Mustika, I., & Richmayati, M. (2021). The effect of green innovation on financial performance with environmental dynamism as moderating variable. Psychology and Education, 58(1), 5228-5234. [CrossRef]

- Feyen, E., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., Natarajan, H., & Saal, M. (2021). Fintech and the digital transformation of financial services: implications for market structure and public policy. BIS Papers(177).

- Fu, Q., Sial, M., Arshad, M., Comite, U., Thu, P., & Popp, J. (2021). The inter-relationship between innovation capability and SME performance: The moderating role of the external environment. Sustainability, 13, 9132. [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D. A. (1987). Competing on the eight dimensions of quality. Harvard Business Review, 65(6), 101-109.

- Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R., & Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the fashion industry. The Perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability, 12(7). [CrossRef]

- Geyer, E., Miller, R., Kim, S., Tobias, J., Nafiu, O., & Tumin, D. (2020). Quality and Impact of Survey Research Among Anesthesiologists: A Systematic Review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 587-599. [CrossRef]

- Goll, I., & Rasheed, A. A. (2004). The Moderating Effect of Environmental Munificence and Dynamism on the Relationship between Discretionary Social Responsibility and Firm Performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 49(1), 41-54.

- Gomes, G., Seman, L., Berndt, A., & Bogoni, N. (2022). The role of entrepreneurial orientation, organizational learning capability and service innovation in organizational performance. Revista de Gestão, 29(1), 39-54. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F., Cisneros, M., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Mogorrón-Guerrero, H. (2020). Innovativeness as a determinant of entrepreneurial orientation: analysis of the hotel sector. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 33(1), 2305-2321. [CrossRef]

- Janicki, H. P., & Wunnava, P. V. (2004). Determinants of foreign direct investment: empirical evidence from EU accession Candidates. Applied Economics, 36, 505-509. [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, A. J., Al-shami, S. A., Majid, I., & Adel, H. (2017). The effect of entrepreneurial orientation of small firms’ innovation. Journal of Technology Management and Technopreneurship, 5 (1), 37-49.

- Kraus, S., Rigtering, J., Hughes, M., & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: a quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev Manag Sci, 6, 161–182. [CrossRef]

- Kreitchmann, R., Abad, F., Ponsoda, V., Nieto, M., & Morillo, D. (2019). Controlling for response biases in self-report scales: forced-choice vs. Psychometric modeling of Likert items. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2309), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2018). Understanding different issues of unit of analysis in a business research. Journal of General Management Research, 5(2), 70-82.

- Lechner, C., & Gudmundsson, S. V. (2014). Entrepreneurial orientation, firm strategy and small firm performance. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 36–60. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Y., Tang, Y. K., Chen, X. L., & Poznanska, J. (2017). The Determinants of Chinese Outward FDI in Countries Along “One Belt One Road”. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 53(6), 1374-1387. [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172. [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 429–451. [CrossRef]

- Meissner, D., & Kotsemir, M. (2016). Conceptualizing the innovation process towards the ‘active innovation paradigm’ trends and outlook. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 5(14), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A., Guldiken, O., Fainshmidt, S., & Pezeshkan, A. (2015). Innovation in India: A review of past research and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 925–958. [CrossRef]

- Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., & Di Fabio, A. (2018). Re-thinking Innovation in Organizations in the Industry 4.0 Scenario: New Challenges in a Primary Prevention Perspective. Fronties in Psychology, 9(30), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, J., & Ruckdeschel, D. (2007). An overview of coefficient alpha and a reliability matrix for estimating adequacy of internal consistency coefficients with psychological research measures. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 105(3), 997-1014. [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D. (2016). The strategic fit between innovation strategies and business environment in delivering business performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 171(1), 241-249. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B., Binsaif, A., & Boukarmi, E. (2019). Business model innovation: A review and research agenda. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 2 (2), 1-20.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: Cumulative empirical evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761-787. [CrossRef]

- Ried, L., Eckerd, S., & Kaufmann, L. (2022). Social desirability bias in PSM surveys and behavioral experiments: Considerations for design development and data collection. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 28(100743), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pena, A. (2021). Assessing the impact of corporate entrepreneurship in the financial performance of subsidiaries of Colombian business groups: under environmental dynamism moderation. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(16). [CrossRef]

- Rubera, G., & Kirca, A. (2012). Firm innovativeness and its performance outcomes: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Marketing, 76, 130-147. [CrossRef]

- Salavou, H. (2004). The concept of innovativeness: should we need to focus? European Journal of Innovation Management, 7(1), 33-44. [CrossRef]

- Saul, E., & Adeline, P. (2018). Privatization in developing countries: What are the lessons of recent experience? The World Bank Research Observer, 33(1), 65-102. [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. (1934). Theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits,capital, credit, interest and the business cycle (Vol. 6). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. H., Kamal, M. A., H. H., & Jiang, L. J. (2019). Does institutional difference affect Chinese outward foreign direct investment? Evidence from fuel and non-fuel natural resources. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 24(4), 670-689. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., Shah, S., & El-Gohary, H. (2022). Nurturing Innovative work behaviour through workplace learning among knowledge workers of small and medium businesses. J Knowl Econ. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G. D., & Hanafi, N. (2020). Innovation and firm performance: Evidence from Malaysian small and medium enterprises. Management Research Journal , 9 (1), 51-59.

- Taber, K. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in scienceeducation. Research in Science Education, 48 , 1273-1296. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S., Nikbin, D., Alam, M., Rahman, S., & Nadarajah, G. (2021). Technological capabilities, open innovation and perceived operational performance in SMEs: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(6), 1486-1507. [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K., & Mueller, S. (2018). Moderating effect of environmental dynamism on the relationship between a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation and financial performance. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 9, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K., Martin, E., & Ali, A. (2020). Enhancing hospitality business performance: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and networking ties in a dynamic environment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90(102605), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Thai, M. (2015). Contingency Perspective. In C. L. Cooper, Wiley Encyclopedia of Management (3rd ed., Vol. 6, pp. 1-5). Wiley onlinelibrary. [CrossRef]

- Ting, H., Wang, H., & Wang, D. (2012). The moderating role of environmental dynamism on the influence of innovation strategy and firm performance. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 3(5).

- UNIDO and GTZ. (2008). Creating an enabling environment for private sector development in sub-Saharan Africa. Vienna: Vienna International Centre.

- Volberda, H. W., Van der Weerdt, N., Verwaal, E., Stienstra, M., & Verdu, A. J. (2012). Contingency Fit, Institutional Fit, and Firm Performance: A Metafit Approach to Organization–Environment Relationships. Organization Science, 23(4), 1040–1054. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V. (2009). Innovation and new product development by SMEs: An investigation of Scottish food and drinks Industry. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Edinburgh Napier University , Edinburgh.

- Wan, D. O., & Lee, F. (2005). Determinants of Firm Innovation in Singapore. Technovation, 25 (3), 261-8.

- Zand, H., & Rezaei, B. (2020). Investigating the impact of process and product innovation strategies on business performance due to the mediating role of environmental dynamism using structural equations modeling. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 17(2), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zehir, C., & Balak, D. (2018). Market dynamism and firm performance relation: The mediating effects of positive environment conditions and firm innovativeness. Emerging Markets Journal, 8(1). 45-51. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).