Submitted:

18 February 2023

Posted:

20 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

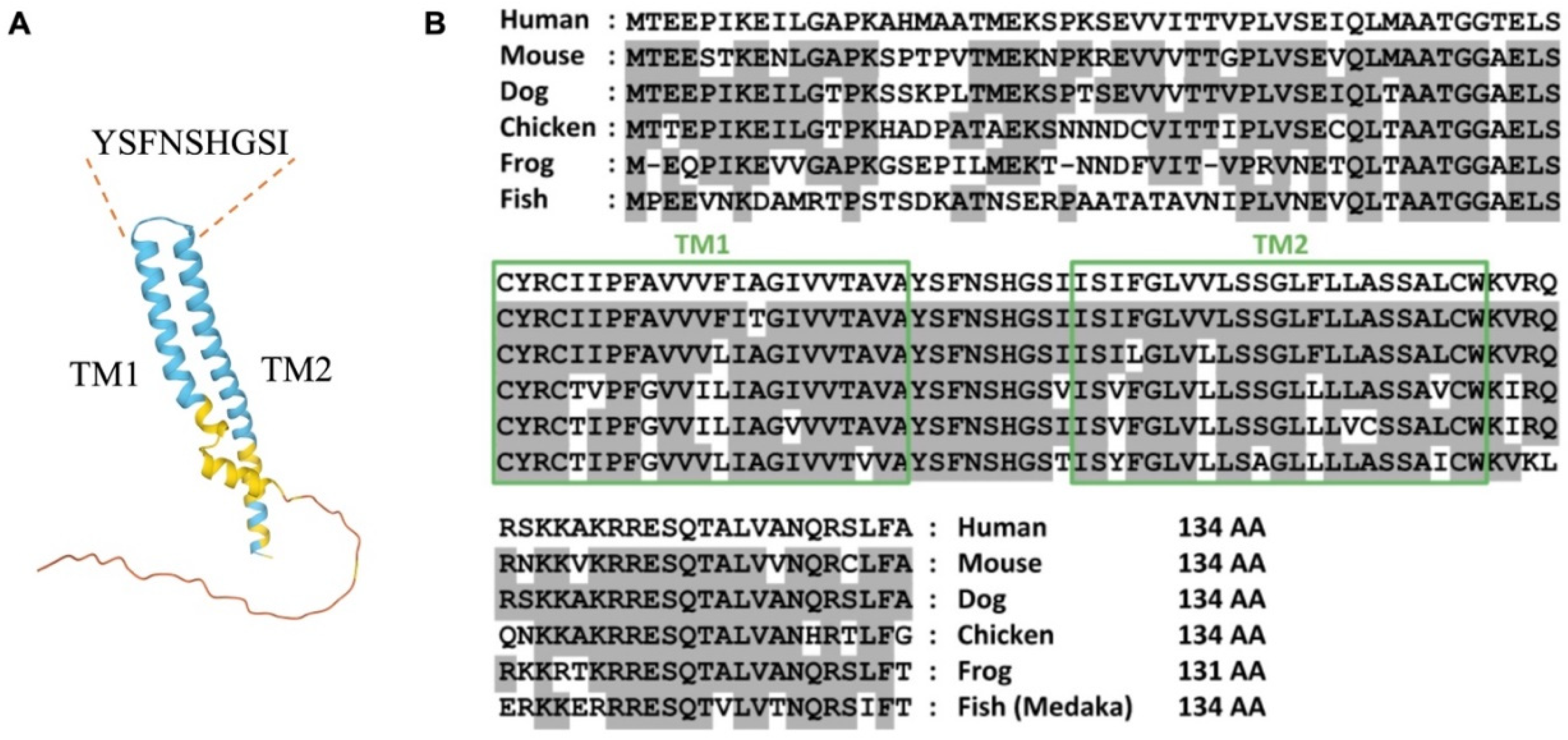

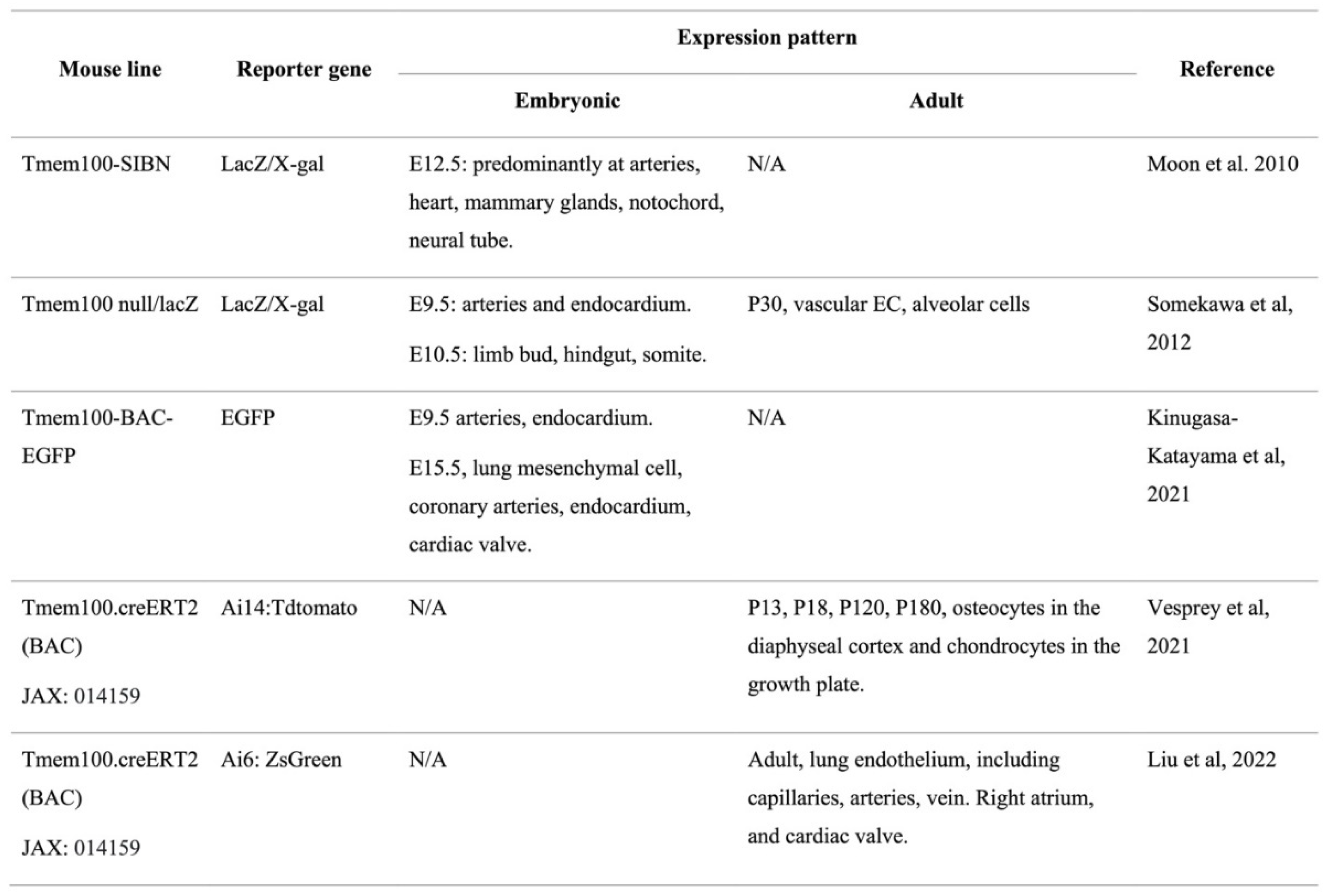

2. TMEM100 and its expression pattern

3. Role of TMEM100

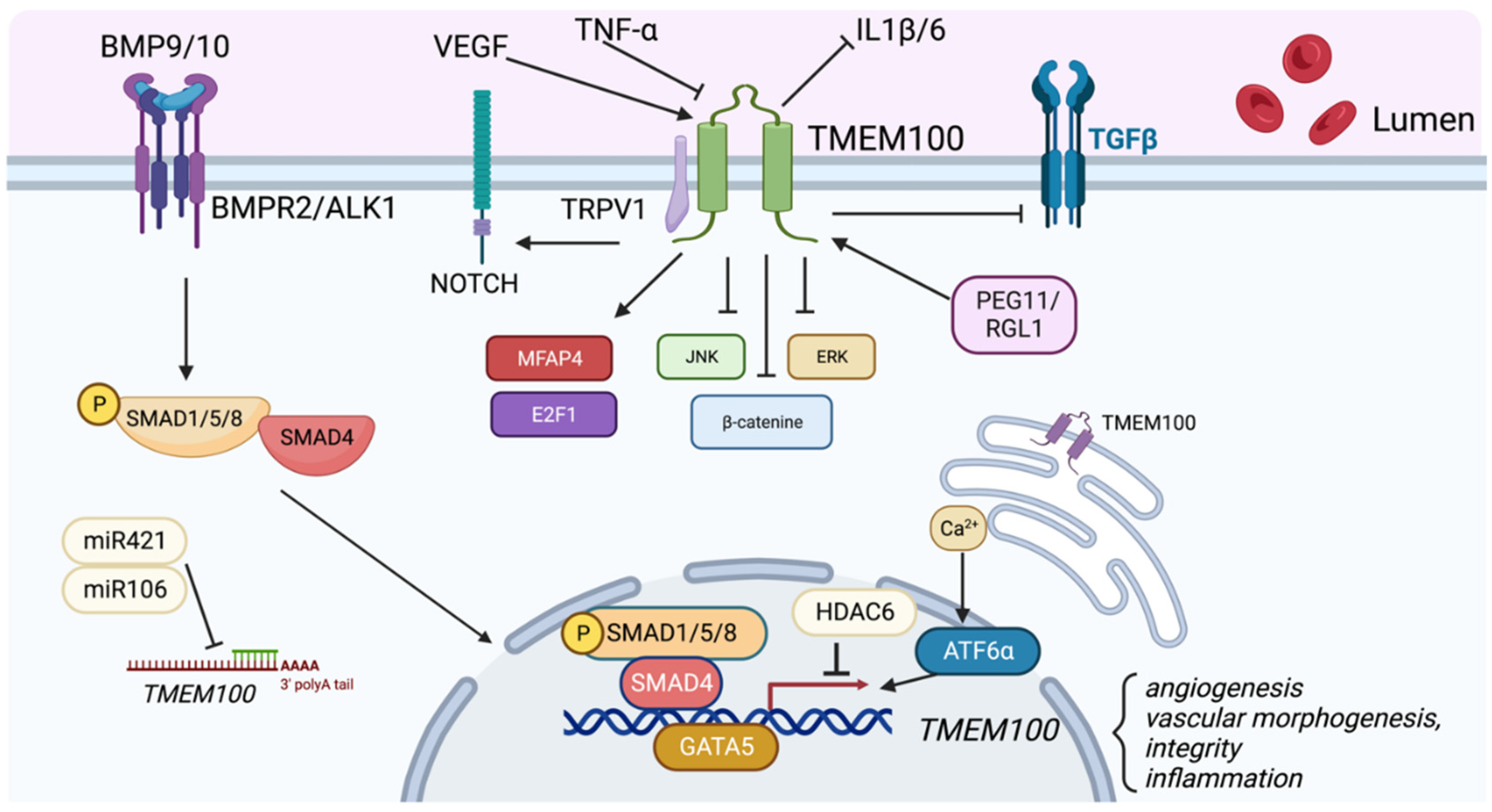

4. Molecular Signaling Affected by TMEM100

5. Regulation of TMEM100 Expression

6. Therapeutic Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1. Rafii S, Butler JM, Ding BS. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature, 2016.

- Garlanda C, Dejana E. Brief Reviews Heterogeneity of Endothelial Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1193–1202.

- Pasut A, Becker LM, Cuypers A, Carmeliet P. Endothelial cell plasticity at the single-cell level. Angiogenesis. 2021;24:311–326.

- Jambusaria A, Hong Z, Zhang L, Srivastava S, Jana A, Toth PT, Dai Y, Malik AB, Rehman J. Endothelial heterogeneity across distinct vascular beds during homeostasis and inflammation. eLife. 2020;9:1–32.

- Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: I. Structure, function, and mechanisms. Circulation Research. 2007;100:158–173.

- Vila Ellis L, Chen J. A cell-centric view of lung alveologenesis. Developmental Dynamics. 2020;1–15.

- Liu B, Peng Y, Yi D, Machireddy N, Dong D, Ramirez K, Dai J, Vanderpool R, Zhu MM, Dai Z, Zhao Y-Y. Endothelial PHD2 deficiency induces nitrative stress via suppression of caveolin-1 in pulmonary hypertension. The European respiratory journal. 2022;33.

- Yi D, Liu B, Wang T, Liao Q, Zhu MM, Zhao YY, Dai Z. Endothelial autocrine signaling through cxcl12/cxcr4/foxm1 axis contributes to severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22:1–11.

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, Meyer C, Kohl SAA, Ballard AJ, Cowie A, Romera-Paredes B, Nikolov S, Jain R, Adler J, Back T, Petersen S, Reiman D, Clancy E, Zielinski M, Steinegger M, Pacholska M, Berghammer T, Bodenstein S, Silver D, Vinyals O, Senior AW, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021.

- Eisenman ST, Gibbons SJ, Singh RD, Bernard CE, Wu J, Sarr MG, Kendrick ML, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Shen KR, Farrugia G. Distribution of TMEM100 in the mouse and human gastrointestinal tract - A novel marker of enteric nerves. Neuroscience. 2013;240:117–128.

- Somekawa S, Imagawa K, Hayashi H, Sakabe M, Ioka T, Sato GE, Inada K, Iwamoto T, Mori T, Uemura S, Nakagawa O, Saito Y. Tmem100, an ALK1 receptor signaling-dependent gene essential for arterial endothelium differentiation and vascular morphogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12064–12069.

- Kalucka J, de Rooij LPMH, Goveia J, Rohlenova K, Dumas SJ, Meta E, Conchinha NV, Taverna F, Teuwen LA, Veys K, García-Caballero M, Khan S, Geldhof V, Sokol L, Chen R, Treps L, Borri M, de Zeeuw P, Dubois C, Karakach TK, Falkenberg KD, Parys M, Yin X, Vinckier S, Du Y, Fenton RA, Schoonjans L, Dewerchin M, Eelen G, Thienpont B, Lin L, Bolund L, Li X, Luo Y, Carmeliet P. Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of Murine Endothelial Cells. Cell. 2020;180:764-779.e20.

- Liu B, Yi D, Yu Z, Pan J, Ramirez K, Li S, Wang T, Glembotski CC, Fallon MB, Oh SP, Gu M, Kalucka J, Dai Z. TMEM100, a Lung-Specific Endothelium Gene. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2022;2022.08.26.504609.

- Moon EH, Kim MJ, Ko KS, Kim YS, Seo J, Oh SP, Lee YJ. Generation of mice with a conditional and reporter allele for Tmem100. Genesis. 2010;48:673–678.

- Kinugasa-Katayama Y, Watanabe Y, Hisamitsu T, Arima Y, Liu NM, Tomimatsu A, Harada Y, Arai Y, Urasaki A, Kawamura T, Saito Y, Nakagawa O. Tmem100 -BAC-EGFP mice to selectively mark and purify embryonic endothelial cells of large caliber arteries in mid- gestational vascular formation. Genesis. 2021;59:1–10.

- Vesprey A, Suh ES, Göz Aytürk D, Yang X, Rogers M, Sosa B, Niu Y, Kalajzic I, Ivashkiv LB, Bostrom MPG, Ayturk UM. Tmem100- and Acta2-Lineage Cells Contribute to Implant Osseointegration in a Mouse Model. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2021;36:1000–1011.

- Vesprey A, Suh ES, Göz Aytürk D, Yang X, Rogers M, Sosa B, Niu Y, Kalajzic I, Ivashkiv LB, Bostrom MPG, Ayturk UM. Tmem100- and Acta2-lineage Cells Contribute to Implant Osseointegration in a Mouse Model. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2021;00:1–12.

- Mizuta K, Sakabe M, Somekawa S, Saito Y, Nakagawa O. TMEM100: A Novel Intracellular Transmembrane Protein Essential for Vascular Development and Cardiac Morphogenesis [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29787135.

- Li DY, Sorensen LK, Brooke BS, Urness LD, Davis EC, Taylor DG, Boak BB, Wendel DP. Defective angiogenesis in mice lacking endoglin. Science (New York, NY). 1999;284:1534–7.

- Urness LD, Sorensen LK, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations in mice lacking activin receptor-like kinase-1. Nature Genetics. 2000;26:328–331.

- Moon EH, Kim YS, Seo J, Lee S, Lee YJ, Oh SP. Essential role for TMEM100 in vascular integrity but limited contributions to the pathogenesis of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Cardiovascular Research. 2015;105:353–360.

- Moon EH, Kim YH, Vu PN, Yoo H, Hong K, Lee YJ, Oh SP. TMEM100 is a key factor for specification of lymphatic endothelial progenitors. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:339–355.

- Karolak JA, Deutsch G, Gambin T, Szafranski P, Popek E, Stankiewicz P. Transcriptome and Immunohistochemical Analyses in TBX4- and FGF10-Deficient Lungs Imply TMEM100 as a Mediator of Human Lung Development. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2022;66:694–697.

- Karolak JA, Gambin T, Szafranski P, Maywald RL, Popek E, Heaney JD, Stankiewicz P. Perturbation of semaphorin and VEGF signaling in ACDMPV lungs due to FOXF1 deficiency. Respiratory Research. 2021;22:1–11.

- Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 Hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2α. Circulation. 2016;133:2447–2458.

- Dai Z, Dai J, Zhao Y-Y. Single-Cell Transcriptomes Identify Endothelial TMEM100 Playing a Pathogenic Role in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. In: ATS. 2020. p. A7863.

- Tada Y, Majka S, Carr M, Harral J, Crona D, Kuriyama T, West J. Molecular effects of loss of BMPR2 signaling in smooth muscle in a transgenic mouse model of PAH. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;292:1556–1563.

- Kim MJ, Min Y, Jeong SK, Son J, Kim JY, Lee JS, Kim DH, Lee JS, Chun E, Lee KY. USP15 negatively regulates lung cancer progression through the TRAF6-BECN1 signaling axis for autophagy induction. Cell Death and Disease. 2022;13:1–13.

- Frullanti E, Colombo F, Falvella FS, Galvan A, Noci S, De Cecco L, Incarbone M, Alloisio M, Santambrogio L, Nosotti M, Tosi D, Pastorino U, Dragani TA. Association of lung adenocarcinoma clinical stage with gene expression pattern in noninvolved lung tissue. International Journal of Cancer. 2012;131.

- Pan L xin, Li L yun, Zhou H, Cheng S qi, Liu Y min, Lian P pan, Li L yun, Wang L le, Rong S jie, Shen C pu, Li J, Xu T. TMEM100 mediates inflammatory cytokines secretion in hepatic stellate cells and its mechanism research. Toxicology Letters. 2019;317:82–91.

- Li H, Cheng C, You W, Zheng J, Xu J, Gao P, Wang J. TMEM100 Modulates TGF- β Signaling Pathway to Inhibit Colorectal Cancer Progression. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2021;2021.

- Han Z, Wang T, Han S, Chen Y, Chen T, Jia Q, Li BB, Li BB, Wang J, Chen G, Liu G, Gong H, Wei H, Zhou W, Liu T, Xiao J. Low-expression of TMEM100 is associated with poor prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. American Journal of Translational Research. 2017;9:2567–2578.

- Wang Y, Ha M, Li M, Zhang L, Chen Y. Histone deacetylase 6-mediated downregulation of TMEM100 expedites the development and progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Human Cell. 2022;35:271–285.

- Liu J, Lin F, Wang X, Li C, Qi Q. GATA binding protein 5-mediated transcriptional activation of transmembrane protein 100 suppresses cell proliferation, migration and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer DU145 cells. Bioengineered. 2022;13:7972–7983.

- Ye Z, Xia Y, Li L, Li B, Chen W, Han S, Zhou X, Chen L, Yu W, Ruan Y, Cheng F. Effect of transmembrane protein 100 on prostate cancer progression by regulating SCNN1D through the FAK/PI3K/AKT pathway. Translational Oncology. 2023;27:101578.

- Xie R, Liu L, Lu X, He C, Li G. Identification of the diagnostic genes and immune cell infiltration characteristics of gastric cancer using bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Frontiers in Genetics [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 10];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.1067524.

- TMEM100 expression suppresses metastasis and enhances sensitivity to chemotherapy in gastric cancer [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 14];Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/hsz-2019-0161/html.

- Park J, Shim J-K, Yoon S-J, Kim SH, Chang JH, Kang S-G. Transcriptome profiling-based identification of prognostic subtypes and multi-omics signatures of glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10555.

- Yu H, Shin SM, Wang F, Xu H, Xiang H, Cai Y, Itson-Zoske B, Hogan QH. Transmembrane protein 100 is expressed in neurons and glia of dorsal root ganglia and is reduced after painful nerve injury. Pain Rep. 2018;4:e703.

- Weng HJ, Patel KN, Jeske NA, Bierbower SM, Zou W, Tiwari V, Zheng Q, Tang Z, Mo GCH, Wang Y, Geng Y, Zhang J, Guan Y, Akopian AN, Dong X. Tmem100 Is a Regulator of TRPA1-TRPV1 Complex and Contributes to Persistent Pain. Neuron. 2015;85:833–846.

- Upregulation of DRG protein TMEM100 facilitates dry-skin-induced pruritus by enhancing TRPA1 channel function [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 14];Available from: https://www.sciengine.com/ABBS/doi/10.3724/abbs.2022180;JSESSIONID=0c361193-dc6b-4214-9cdc-447e5779b08b.

- Muley A, Kim Uh M, Salazar-De Simone G, Swaminathan B, James JM, Murtomaki A, Youn SW, McCarron JD, Kitajewski C, Gnarra Buethe M, Riitano G, Mukouyama Y suke, Kitajewski J, Shawber CJ. Unique functions for Notch4 in murine embryonic lymphangiogenesis. Angiogenesis [Internet]. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ren D, Ju P, Liu J, Ni D, Gu Y, Long Y, Zhou Q, Xie Y. BMP7 plays a critical role in TMEM100-inhibited cell proliferation and apoptosis in mouse metanephric mesenchymal cells in vitro. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology - Animal. 2018;54:111–119.

- Zheng Y, Zhao Y, Jiang J, Zou B, Dong L. Transmembrane Protein 100 Inhibits the Progression of Colorectal Cancer by Promoting the Ubiquitin/Proteasome Degradation of HIF-1α. Frontiers in Oncology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 16];12. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.899385.

- Kinugasa-Katayama Y, Watanabe Y, Hisamitsu T, Arima Y, Liu NM, Tomimatsu A, Harada Y, Arai Y, Urasaki A, Kawamura T, Saito Y, Nakagawa O. Tmem100-BAC-EGFP mice to selectively mark and purify embryonic endothelial cells of large caliber arteries in mid-gestational vascular formation. Genesis. 2021;59:1–11.

- Chen X, Orriols M, Walther FJ, Laghmani EH, Hoogeboom AM, Hogen-Esch ACB, Hiemstra PS, Folkerts G, Goumans MJTH, ten Dijke P, Morrell NW, Wagenaar GTM. Bone morphogenetic protein 9 protects against neonatal hyperoxia-induced impairment of alveolarization and pulmonary inflammation. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017;8:1–17.

- Kitazawa M, Tamura M, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F. Severe damage to the placental fetal capillary network causes mid- to late fetal lethality and reduction in placental size in Peg11/Rtl1 KO mice. Genes to Cells. 2017;22:174–188.

- Li T, Conroy KL, Kim AM, Halmai J, Gao K, Moreno E, Wang A, Passerini AG, Nolta JA, Zhou P. Role of MEF2C in the Endothelial Cells Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2023;sxad005.

- Li Y, Cho H, Wang F, Canela-Xandri O, Luo C, Rawlik K, Archacki S, Xu C, Tenesa A, Chen Q, Wang QK. Statistical and Functional Studies Identify Epistasis of Cardiovascular Risk Genomic Variants From Genome-Wide Association Studies. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9:e014146.

- Kadonaga T, Sakabe T, Kidokoro Y, Haruki T, Nosaka K, Nakamura H, Umekita Y. Gene expression profiling using targeted RNA-sequencing to elucidate the progression from histologically normal lung tissues to non-invasive lesions in invasive lung adenocarcinoma. Virchows Archiv. 2022;480:831–841.

- Zhuang J, Huang Y, Zheng W, Yang S, Zhu G, Wang J, Lin X, Ye J. TMEm100 expression suppresses metastasis and enhances sensitivity to chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Biological Chemistry. 2020;401:285–296.

- Hong Y, Si J, Xiao B, Xiong Y, Dai C, Yang Y, Li S, Ma Y. circ_0000567/miR-421/TMEM100 Axis Promotes the Migration and Invasion of Lung Adenocarcinoma and Is Associated with Prognosis. Journal of Cancer. 2022;13:1540–1552.

- Ma J, Yan T, Bai Y, Ye M, Ma C, Ma X, Zhang L. TMEM100 negatively regulated by microRNA-106b facilitates cellular apoptosis by suppressing survivin expression in NSCLC. Oncology Reports. 2021;46:1–13.

- Hong Y, Si J, Xiao B, Xiong Y, Dai C, Yang Y, Li S, Ma Y. circ_0000567/miR-421/TMEM100 Axis Promotes the Migration and Invasion of Lung Adenocarcinoma and Is Associated with Prognosis. J Cancer. 2022;13:1540–1552.

- Kuboyama A, Sasaki T, Shimizu M, Inoue J, Sato R. The expression of Transmembrane Protein 100 is regulated by alterations in calcium signaling rather than endoplasmic reticulum stress. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2018;82:1377–1383.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).