1. Background

As a critical source of human capital investment, health plays a vital role in human development and improves human well-being[

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, over the past few decades, China has suffered heavy environmental pollution due to rapid economic growth and relaxed environmental protection policies. The resulting ecological deterioration has yielded negative monetary impacts and abundant non-monetary losses, such as residents' physical and mental health and human capital damages via multiple channels concerning water, land, and air [

5,

6,

7,

8]. For example, air pollution data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China suggested that 338 cities experienced heavy pollution for 2,311 days in 2017. Only 27.2% of these cities reached the standard of good air quality. Moreover, a report published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016 stated that about 140 out of every 100,000 people in China died from ambient and household air pollution. This is consistent with numerous field and lab experiments that have confirmed environmental pollution as one of the critical reasons for the continuous deterioration of human health and mortality [

9,

10]. Despite enacting national and local environmental policies to improve the well-being of communities, environmental pollutants continue to threaten the health of urban and rural residents in China [

11].

1.1. Rural women in farming

Over the past decade, urban and rural residents’ livelihoods in China have notably improved due to economic growth and development. Yet, there is still a disparity in employment opportunities, medical services, and household income for those in rural areas [

12,

13]. This has led to a preponderance of young and middle-aged farmers migrating to cities over recent decades, seeking improved employment opportunities and higher income. This, in turn, has led to several women and children being left in rural areas, so-called “left-behind” women and children. This places strain on women in rural areas who must then provide household public goods (e.g., caring for the elders and children) while simultaneously engaging with greater frequency in agricultural production activities. In fact, rural women are now playing a crucial role in the agriculture systems. Data from the Third National Agricultural Census of China described that over 149 million female farmers were involved in agricultural practice, accounting for more than 47% of the total number of farmers in China by the end of 2016. This has been a more recent transition than in traditional agricultural structures where men dominated the workforce. Scholars have described the phenomenon of numerous rural women participating in agricultural production as "agricultural feminization" [

14,

15].

Previous studies have documented that female farmers are more vulnerable than male farmers [

16,

17]. Typically, female farmers may be less informed about environmental health risks and knowledge [

16]. And with the increasing frequency of engaging in agricultural activities for rural women, their exposure to farm point and non-point source pollution (such as pesticide exposure and excess fertilizers) increases exponentially. As a result, the left-behind female farmers in rural China are more vulnerable to severe health risks and less medical care. The National Health Commission of China revealed that chronic diseases among rural women in China increased from 13.5% to 32.3% between 2003 and 2013. The inadequacy of essential medical facilities in rural areas remains problematic. For example, the number of health professionals per thousand people in urban areas was 11.10 in 2019, while that of their rural counterparts was only 4.96 [

18,

19]. Thus, there is a gap between the supply of medical and health public goods versus the demand for such public goods in rural China [

20].

1.2. Environmental pollution and health risks

The extant literature indicates that those suffering from illness, regardless of income level, will likely suffer from fewer opportunities concerning welfare, freedom, and capability [

21]. Moreover, those with lower health status often confront more diseases, increasing the household's financial burden and leaving some in poverty, i.e., the "health-poverty" trap [

11]. In addition to these considerations, environmental pollution can bring both physical (somatic) health problems and disease and mental health problems such as depression [

22]. However, fewer empirical studies have considered both of these two types of health problems simultaneously(e.g., [

23]).

Previous studies have shown that environmental pollution has increased public health risks, especially for rural residents [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Complicating these risks is that, compared to their urban counterparts, the per capita income for rural residents is relatively lower despite having a higher risk of medical expenditure and pension. In addition, historically, long-term investments into fundamental public health facilities in rural areas have been scarce and unequally distributed [

30]. To address the increasingly severe health risks of rural residents, since 2003, China’s government has gradually established a series of public health systems, such as the new rural cooperative medical system (NRCMS) and the new rural social endowment insurance (NRSEI). The NRCMS is the most comprehensive coverage system, covering 95% of rural residents since 2010 [

5]. Many studies have demonstrated the positive effects of the NRCMS on public health. [

22] found that NRCMS has improved service availability and has reduced disease economic burden. However, despite these documented improvements, others have argued that NRCMS’s effectiveness is not ideal and has a limited capability for reducing the expenditures of severe diseases and the poverty induced by such diseases[

31,

32]. In fact, even the above-cited studies that reported on NRCMS’ improvements on health have also reported its lower impacts on reducing the economic risk of illness and promoting equity in health services [

22].

1.3. Purpose of the study and contribution to the literature

The present study examined the relationship among environmental knowledge (EK), pollution, health investment, and health status of women residing in rural regions in China. This research contributes to the body of knowledge by addressing a number of limitations identified in the extant literature. First, previous studies [

33,

34] have only assessed the impact of health investment represented by NRCMS on residents' physical and mental health from the public perspective but have not examined this relationship from a personal health investment perspective. Second, prior research on residents' health has primarily focused on adolescents, infants, middle-aged and older people [

22,

35,

36]. Less attention, however, has been paid to rural women. Thirdly, fewer studies have investigated the role of EK on public health [

16,

37,

38]. Awareness and cognition are fundamental prerequisites for ensuring behavior [

39]. Hence, the present study aimed to explore the association of EK and public health with a nationally representative sample of rural women in China and investigated the mediating effects of public and personal health investments.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and sample

Data for this study came from the 2013 Chinese General Social Survey (2013CGSS), a nationally representative dataset of Chinese households (Xiang et al., 2020). CGSS datasets are publicly available and can be downloaded via

http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/. The Chinese General Social Survey program started in 2003 and has been implemented yearly, save for 2007. The 2013CGSS employs a nationwide stratified sampling method, collecting from 11,438 urban and rural residents in 28 provinces in China. Specifically, we used the 2013 wave because it was the only year the dataset contained a set of 10 items measuring respondents’ EK and questions regarding physical and mental health variables. After retrieving the dataset, we conducted several data cleaning and preparation methods. We delimited the data to the population of interest—female respondents residing in rural areas—and removed missing values for the main variables of interest. The resulting sample used for analysis was composed of 1,930 women in rural China.

2.2. Variables and Measures

2.2.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study was defined as health status. Based on the literature and data availability [

22,

40], we divided this variable into two dimensions: physical and mental health. Women's physical health was measured using a 5-point Likert scale question (i.e., "What is your health status?"), where 5 indicated very good health, and 1, very poor. For the purpose of this study’s analysis, a dummy variable was created, where response choices “very poor” and “poor” were set as 0 (“poor physical health”) and 1 (“good physical health”), otherwise. Next, we used question A17 in the 2013CGSS codebook to measure rural women's mental health. The question asked respondents about the frequency to which they have felt depressed in the last four weeks—previous studies have used similar questions as a proxy for mental health[

22,

41]. The question was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where a score of 5 points denoted “always,” and 1 meant “never.” A dummy variable was created using response choices: “often” and “always” were combined and represented “poor mental health” and otherwise denoted “good mental health.”

2.2.2. Independent variable

The current study used EK as the primary independent variable. We calculated EK scores based on women’s responses to ten questions (See

Appendix A for the list of questions). In terms of scoring, we assigned 1 point for correct answers, 0 for incorrect responses, and for those who selected “don’t know”—this scoring process and method is informed by [

42]. The sum of scores received for all ten questions was used to generate the variable EK.

2.2.3. Covariates

Our literature review identified a set of influential physical and mental health factors among rural communities and women in particular [

22,

32,

43,

44]. For example, [

45] found that climate variables (e.g., high temperature and reduced rainfall), social-demographic factors, and economic variables affected farmers' mental health in Australia. Similarly, [

46] showed that rural women's physical and mental health were also determined by education and employment. In this study, we classified covariates into three categories: personal characteristics, family characteristics, and health-related variables. The respondents’ personal characteristics included age, educational attainment, and party affiliation. We hypothesized that the elder respondents, those with higher education, would be more likely to exhibit good health [

22,

46]. In rural China, residents who are members of the communist party tend to show higher social status, which often translates to a better quality of life and health[

47]. The second category of covariates is family characteristics. Our study uses the household income variable to describe family characteristics. Generally, more household income denotes more healthcare choices and a higher capacity to pay medical bills [

48]. We use the logarithm form for this variable to reduce the model's heteroscedasticity [

49].

We anticipated that the social network would benefit women's health, especially mental health in rural China, because the more frequency of social contact with neighbors or relatives, the higher the possibility of limiting their mental problems [

50,

51]. Additionally, our covariates also contain the variables of health investments, such as medical system participation, commercial insurance purchasing, and physical exercise [

51]. The definition and descriptive statistics of variables are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

| Variables |

Item (Question number in the codebook) |

Operationalization |

Number of Obs. |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Min |

Max |

| Self-reported health |

In your opinion, what is your health status? (A15)

|

1=very good, good, or fair; 0= poor or very poor. Binary variable. |

1930 |

0.748 |

0.434 |

0 |

1 |

| Mental health |

In the past four weeks, what frequency do you feel depressed? (A17) |

1=often or always; 0=never, rarely, or sometimes. Binary variable |

1929 |

0.104 |

0.305 |

0 |

1 |

| Environmental Knowledge |

See appendix A for the complete list of items (B25)

|

Calculated by ten questions, 1 point for the correct answer, 0 points for “don’t know” and wrong answer. Continuous variable. |

1929 |

3.184 |

2.505 |

0 |

10 |

| Age |

What is your birthdate? (A3)

|

Calculated by the answer minus 2013 from respondents, Continuous variable |

1930 |

49.336 |

15.462 |

18 |

90 |

| Education level |

What is your highest education level? (A7a) |

High school or more =1, less than high school=0; Binary variable |

1930 |

0.070 |

0.256 |

0 |

1 |

| Party affiliation |

What is your political status? (A10) |

Party member=1; No party member=0; Binary variable. |

1930 |

0.017 |

0.130 |

0 |

1 |

| Household income |

What was your family income in 2012?

(A62) |

Continuous variable. |

1930 |

33940.07 |

37541.71 |

0 |

645000 |

| Family size |

How many people live in your household unit? (A63) |

Continuous variable. |

1930 |

3.277 |

1.491 |

1 |

11 |

| Social network |

How often have you socialized in your free time in the past year? (A31) |

1=never; 2=rarely; 3=sometimes; 4=often; 5=always. Ordinal variable |

1930 |

3.119 |

1.024 |

1 |

5 |

| NRCMS participation |

Did you or your family participate in the new rural cooperative medical system in the past year? (A61) |

1=yes; 0=others; Binary variable |

1930 |

0.939 |

0.239 |

0 |

1 |

| Physical exercise |

What is the frequency of exercise in your free time in the past year? (A30) |

1=never; 2=rarely; 3=sometimes; 4=often;5=always. Ordinal variable. |

1924 |

1.401 |

0.944 |

1 |

5 |

| Commercial Insurance |

Did you buy some commercial health insurance in the past year? (A61) |

1=yes; 0=others; Binary variable |

1930 |

0.036 |

0.187 |

0 |

1 |

| Television |

In the past year, what is the frequency of your television use? (A28) |

1=never; 2=rarely; 3=sometimes; 4= often; 5=always. Ordinal variable. |

1929 |

4.073 |

0.976 |

1 |

5 |

| Internet |

In the past year, what is the frequency of your internet use? (A28)

|

1=never; 2= rarely; 3=sometimes; 4=often; 5=always. Ordinal variable |

1929 |

1.474 |

1.055 |

1 |

5 |

| Body Mass Index |

Weight and height; (A13-A14) |

The ratio of weight to the square of height. Continuous variable. |

1912 |

22.101 |

4.586 |

13.672 |

142.399 |

As shown in table 1, the means of self-reported and mental health of respondents in the sample were 0.748 and 0.104, respectively. In other words, most respondents reported having good physical and mental health status. As for the variable EK, the mean was 3.184 (out of ten possible points) with a standard deviation of 2.505, indicating that female residents in rural China scored low in the environmental knowledge index. The health investment variables suggested that the majority of respondents (93.9%) in rural China had participated in the New Rural Cooperative Medical System (NRCMS), which is consistent with the participation rate provided in official governmental data [

52]. Importantly, only 3.6% of respondents indicated having purchased commercial insurance. Also, females in our samples exhibited low levels of physical exercise activities. Finally, rural women were unlikely to be party members, and their average social network was 3.119, suggesting a low involvement in social activities.

2.3 Model selection

The present study aimed to explore the impacts of rural women's EK on health status in China. As such, the dependent variable is the self-reported health status of rural Chinese women, including subjective physical health and mental health, and the leading independent is EK. In addition, we controlled for a set of covariates: household income, age, and education level. Previous studies have deemed the control variables significant health status predictors [

51,

53]. The multi-linear regression model can be represented as follows:

Where, denotes the ith women's health status in rural China, which involves two dimensions, namely, self-reported health and mental health. We estimated these two variables separately; refers to the score of the ith respondent's EK. And the represents a vector of control variables influencing women's health in rural China. Lastly, represents the error term for the model.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of EK on health status among rural women

We hypothesized that EK, directly and indirectly, impacted rural women's physical and mental health. To empirically test such hypotheses, we employed a series of regressions.

Table 2 shows the logit model results for EK and self-reported and mental health.

As expected, the results in table 2 showed that both self-reported health and mental health were positively affected by women's EK, significant at a 0.1% significance level. The marginal effects of EK on women's physical health and depression were 0.016 and -0.012, respectively. In addition, the respondents' age was negatively correlated with health status. Women's social network and household income were positively associated with self-reported and mental health and were significant at a 1% significance level. Contrary to previous findings [

52,

54], we found no evidence that NRCMS participation and holding commercial insurance influenced women's health in rural areas.

3.2. The endogeneity and robustness

3.2.1. Instrumental variable methods for endogeneity

Our basic model examined the associations between EK and women's health status. However, the model did not allow for verifying causal effects for these two variables because of the potential endogeneity. Theoretically, the endogeneity of a regression model has at least three sources[

55]. First, the simultaneity implies that the dependent variables (X) cause the independent variable (Y), while Y also causes X. Second, the omitted variables, or covariates related to the error term. Lastly, the measurement error. The measurement error describes the observation errors on variables or data collection errors. The data is retrieved from the CGSS2013, a nationally representative dataset with a rigorous sampling procedure [

44,

53]. The probability of measurement error in this dataset is reasonably low. Thus, the present study only focuses on the endogenous problems caused by omitted variables and simultaneity.

In our study, the simultaneity of rural women's EK and health status may exist, suggesting that higher EK improves women's physical and mental health. Meanwhile, women with chronic health conditions may pay more attention to the reasons related to their health (e.g., exposure to environmental pollution) and, thus, have greater awareness and knowledge of environmental issues. Likewise, our regression models may also omit influential variables that affect women’s health status. Hence, we employed instrumental variable (IV) methods to re-estimate the regression model and corrected the estimation bias from potential endogeneity.

The basic idea of the IV method is to find one or more reasonable IVs, which should satisfy the following properties: First, the IVs should be exogenous, indicating no correlation with the error term,

.; the second property is relevance, in other words, the IVs must be correlated with the independent variables,

X [

55]. Based on data availability in 2013CGSS, we used two variables as the IVs: television and internet use (see table 1 for description). Previous research has shown that television and the internet are crucial channels for rural residents to access information about health [

56]. Yet, these channels may not be directly associated with their health status. Thus, we can reasonably infer that rural women who watch television or use the internet with a higher frequency may have a higher level of EK because information related to environmental pollution can be accessed through these two channels. However, using and accessing these two communication channels do not directly determine their physical and mental health status.

Table 3.

the results of the IV-probit model.

Table 3.

the results of the IV-probit model.

| Variables |

Self-reported health |

Marginal effects |

Mental health |

Marginal effects |

| Environmental knowledge |

0.393*** |

0.189*** |

-0.312*** |

-0.065*** |

| (0.025) |

(0.041) |

(0.067) |

(0.024) |

| Control variables |

Control |

- |

Control |

|

| Constant |

-0.899** |

|

0.810 |

|

| (0. 318) |

- |

(0.438) |

- |

| Wald test |

35.17*** |

6.83** |

|

| Log-likelihood |

-5199.87 |

-4855.51 |

|

| F statistic |

44.04*** |

44.02*** |

|

| N |

1916 |

1915 |

|

The results for the estimated IV-probit model are presented in table 3. The values of the Wald test of exogeneity were 35.17 and 6.83 for self-reported and mental health, respectively. The results were significant at the 0.1% and 1% significance levels. The results of the Wald test rejected the null hypothesis that all variables are exogenous, supporting the need to use the IV methods to correct the potentially biased results [

57]. Also, we tested the strength of our instrument variables. The values of F-statistic were 44.03 and 44.02 for the two models, which are larger than the criteria of 10 and significant at a 0.1% significance level. These results suggested that the IVs were valid [

58]. Women's EK had significant positive effects on their self-reported and mental health. The marginal effects of EK were 0.189 and -0.065 on women's physical and mental health, respectively; these results are significant at a 0.1% level. When comparing these results with the logit model results, the effects in the IV-probit model are greater; in other words, the logit model may have underestimated the impact of EK on physical and mental health when endogeneity issues are unaccounted for [

55].

3.2.2 Robustness check

Prior studies showed that individuals' self-reported health might be a highly subjective measure and thus may not truly mirror respondents’ health status. The mismatch between perceived health status and actual health status may lead to unreliable results and conclusions (Crossley & Kennedy, 2002). Hence, to assess the reliability and robustness of our results, we used the body mass index (BMI) variable as a proxy of health status. BMI was calculated by dividing the body mass (weight) by the square of the body height. Consistent with the definition and thresholds provided by the World Health Organization [

59], we defined healthy individuals as those with BMI values between 18.5 and 23.9. Respondents with BMI values lower than 18.5 (malnourished) or higher than 23.9 (overweight and obese) were deemed unhealthy. A binary variable was created using this framework. Furthermore, considering the variables of self-reported and mental health were measured by 5-point Likert scales, we then estimated an ordered logit model to check the robustness of our results.

Table 4 provides the results of robust tests. The second and third columns of

Table 4 describe the results of the ordered logit model with the dependent variable of self-reported physical and mental health, measured by five-point Likert scales. The last column in table 4 shows the results of the robust test with the dependent variable of BMI. Consistent with the results in the basic model and the IV-probit model, the robustness check models showed that EK had a significant and positive effect on women's health status in rural China. In other words, an increase in EK is associated with improved health status among women in rural China.

3.3 Further exploration: the mediation effects of health investment

The previous sections examined the direct connections between EK and physical and mental health for women in rural China. However, these results do not capture the pathways for the effects of EK on women's health. Hence, in this section, we examined how EK may influence women's physical and mental health through the mediating effects of health investments. Individuals' environmental cognition may affect their behavior [

39]. EK can increase women's cognition and awareness about environmental pollution and incidentally lead to health investment and pro-environmental behaviors [

42].

A set of mediation models was estimated to analyze the mediating effects of health investments. This study mainly explored the mediation effects of health investments in rural China: public health investment (e.g., rural women's participation in the NRCMS) and private health investment (e.g., physical exercise and commercial medical insurance).

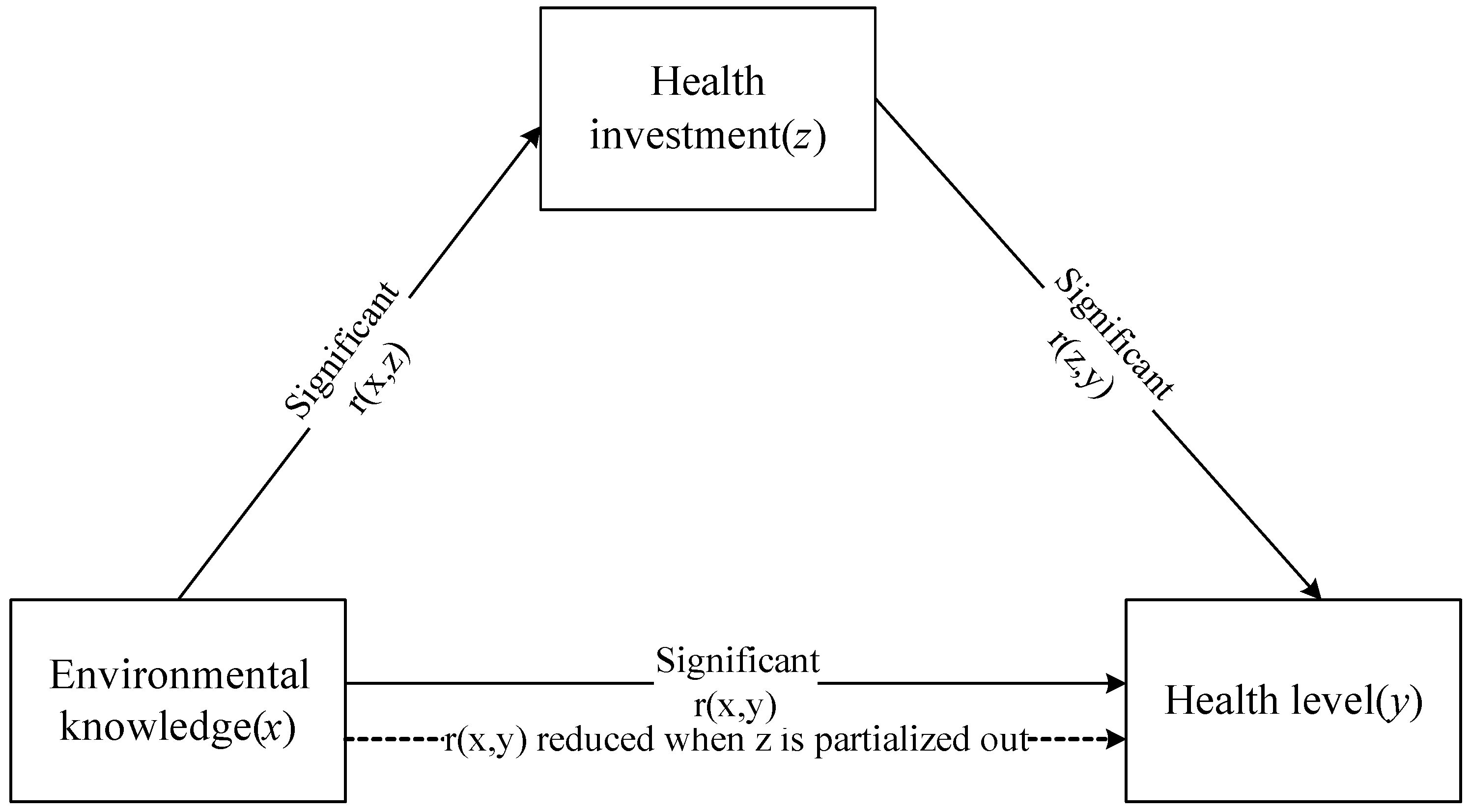

Figure 1 illustrates the paths explored in the mediation models.

The mediation effects can be examined using a Sobel test (Baron &Kenny, 1986; Preacher& Hayes, 2008).

Table 5 shows the results of the Sobel test for the mediation effects of health investments.

Table 5 indicates that physical exercise significantly mediated EK and women's mental health. Still, the mediation effects of physical activity on EK and self-reported health were not significant. As shown, the regression coefficients of EK were reduced after adding the mediator, decreasing from 0.053 to 0.051 and from -0.038 to -0.035, respectively. The mediation effect of physical exercise was significant at a significance level of 1%. Moreover, physical activity has a significant impact on women's mental health.

Table 6 shows the mediation effects of NRCMS participation on EK and self-reported physical and mental health for women in rural China. However, the mediation effects were not significant, suggesting that public health investments (i.e., NRCMS) may not influence women's physical and mental health in rural China. This paper also examined the mediation effects of commercial insurance (See

Appendix B). The results also showed that there is no evidence to support that commercial insurance impacts women's health in rural China.

4. Concluding remarks

Rural China has undergone a profound economic transformation over the past decades [

60]. While China has made several developments in terms of poverty alleviation since 2020, there are still several social issues in rural China that need to be addressed, including environmental pollution, health care disparities, and residents' welfare. Using the data from the 2013CGSS, our study investigated the relationship between rural women's EK and their physical and mental health. We posited that environmental knowledge positively influences rural women's physical and mental health. Our findings, including the robustness checks, also confirmed these conclusions. Nevertheless, contrary to prior studies[

61,

62], we did not find any evidence to support that the participation of NRCMS and purchasing of commercial insurance significantly impacted women's physical and mental health. In other words, our results suggested that public health programs, such as NRCMS, did not provide a remarkable and direct impact on women's health status. Moreover, the mediation analysis indicated that women's EK did not influence their health status through the pathway of public health investments. In contrast, personal health investments, such as physical exercise, benefit women's mental health; while purchasing private, commercial insurance did not appear to affect health status. Finally, our study indicated that social networks might help promote women's health, particularly mental health. Thus, our findings have implications for formulating public health and wellness programs in China, and by extrapolation, in other developing nations. First, women remain among the most vulnerable population with greater health risks from environmental pollution exposure and relatively less medical care in the rural areas of the developing world (e.g., [

63]). Though China has executed a relatively comprehensive public health system since 2003, our study found that this system might not fully address the health needs of women, particularly those living in rural settings.

Table 5.

Mediation test of physical exercise on EK and women's physical and mental health.

Table 5.

Mediation test of physical exercise on EK and women's physical and mental health.

| Variables |

Model 1

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

Model 2

Dependent variable: physical exercise |

Model 3

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

Model 4

Dependent variable: mental health |

Model 5

Dependent variable: physical exercise |

Model 6

Dependent variable: mental health |

| Environmental knowledge |

0.053***(0.011) |

0.051***(0.009) |

0.051***(0.011) |

-0.038***(0.009) |

0.051***(0.009) |

-0.035***(0.009) |

| Physical exercise |

- |

- |

0.042(0.027) |

- |

- |

-0.055*(0.023) |

| Control variables |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

| N |

1923 |

1923 |

1923 |

1922 |

1922 |

1922 |

| Adjusted R2 |

0.175 |

0.077 |

0.176 |

0.059 |

0.077 |

0.062 |

| F |

59.25*** |

23.75*** |

52.19*** |

18.34*** |

23.72*** |

16.79*** |

Table 6.

Mediation test of the medical system on EK and women's physical and mental health.

Table 6.

Mediation test of the medical system on EK and women's physical and mental health.

| Variables |

Model 1

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

Model 2

Dependent variable: the medical system |

Model 3

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

Model 4

Dependent variable: mental health |

Model 5

Dependent variable: the medical system |

Model 6

Dependent variable: mental health |

| Environmental knowledge |

0.053***(0.011) |

-0.001 (0.002) |

0.053***(0.011) |

-0.038***(0.009) |

-0.001(0.002) |

-0.038**(0.009) |

| NRCMS participation |

- |

- |

-0.081(0.101) |

- |

- |

-0.064(0.088) |

| Control variables |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

Control |

| N |

1929 |

1929 |

1929 |

1928 |

1928 |

1928 |

| Adjusted R2

|

0.175 |

0.004 |

0.175 |

0.059 |

0.004 |

0.059 |

| F |

59.60*** |

2.02* |

52.22*** |

18.17*** |

2.01 |

15.96*** |

Supplementary Materials

No supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Y.L. and J.R-M. contributed equally to this work. Y.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Validation. J.R.-M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing— Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Validation, Project administration, Funding acquisition. B.R.C.: Writing—Reviewing and Editing. M.L.: Writing—Reviewing and Editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Florida International Center (UFIC)’s Global Fellowship Award, the UFIC Collaborative Faculty Team Project, and the China Scholarship Council (No. 201906760081).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank the Renmin University of China and the CGSS program for providing the dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

We use data from the 2013 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). The CGSS employs a stratified multi-stage probability sample designed to produce a representative sample of Chinese residents.

Environmental Knowledge questions (response choices: a. True, b. False, c. Don’t Know):

1. Vehicle exhaust poses no threat to human health.

2. Excessive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides can cause environmental damage

3. The use of phosphorous washing powder will not cause water pollution

4. Fluorine discharge from refrigerators can be a factor that damages the ozone layer in the atmosphere

5. Burning coal does not affect acid rain

6. Species depend on each other, and the disappearance of a species has a ripple effect

7. In the air quality report, level III means better air quality than the level I

8. Single species of trees are more likely to cause diseases and pests

9. In the water pollution report, water quality V (5) means better than water quality I (1)

10. An increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could be a climate warming factor

Appendix B

Table 7.

Mediation test of commercial insurance on EK and women's physical health.

Table 7.

Mediation test of commercial insurance on EK and women's physical health.

| Variables |

Model 1

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

Model 2 Dependent variable: commercial insurance |

Model 3

Dependent variable: self-reported health |

| Environmental knowledge |

0.053***(0.011) |

0.004*(0.002) |

0.053***(0.011) |

| Commercial Insurance |

- |

- |

0.130(0.130) |

| Control variables |

Control |

Control |

Control |

| N |

1929 |

1929 |

1929 |

| Adjusted R2

|

0.175 |

0.020 |

0.175 |

| F |

59.34*** |

6.61*** |

52.27*** |

Table 8.

Mediation test of commercial insurance on EK and women's mental health.

Table 8.

Mediation test of commercial insurance on EK and women's mental health.

| Variables |

Model 4

Dependent variable: mental health |

Model 5

Dependent variable: commercial insurance |

Model 6

Dependent variable: mental health |

| Environmental knowledge |

-0.038***(0.009) |

0.004(0.002) |

-0.038***(0.009) |

| Commercial Insurance |

- |

- |

-0.081(0.113) |

| Control variables |

Control |

Control |

Control |

| N |

1928 |

1928 |

1928 |

| Adjusted R2 |

0.059 |

0.020 |

0.059 |

| F |

18.17*** |

6.60*** |

15.98*** |

References

- Grossman, M. On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health. Journal of Political Economy 1972, 80, 223–255. [CrossRef]

- Graham, C. Happiness And Health: Lessons—And Questions—For Public Policy. Health Affairs 2008, 27, 72–87. [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Will Raising the Incomes of All Increase the Happiness of All? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 1995, 27, 35–47. [CrossRef]

-

World Happiness Report 2013; John, H., Richard, L., Jeffrey, S., Eds.; New York, 2015;

- Yang, M. Demand for Social Health Insurance: Evidence from the Chinese New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme. China Economic Review 2018, 52, 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Song, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Meng, J.; Sweetman, A.J.; Jenkins, A.; Ferrier, R.C.; Li, H.; Luo, W.; et al. Impacts of Soil and Water Pollution on Food Safety and Health Risks in China. Environment International 2015, 77, 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Sawut, R.; Kasim, N.; Maihemuti, B.; Hu, L.; Abliz, A.; Abdujappar, A.; Kurban, M. Pollution Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in the Vegetable Bases of Northwest China. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 642, 864–878. [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Mannucci, P.M. Impact on Human Health of Climate Changes. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2015, 26, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, P.; Yang, F.; Sun, D.; Zhang, D.-X.; Zhou, Y.-K. Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution and Human Health Risks in Urban Soils around an Electronics Manufacturing Facility. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 630, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J. Air Pollution and Health. The Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e4–e5. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, W. Does Air Pollution Affect Public Health and Health Inequality? Empirical Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 203, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Österle, A. Rural-Urban Disparities in Unmet Long-Term Care Needs in China: The Role of the Hukou Status. Social Science & Medicine 2017, 191, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, L.; Liang, H.; Ding, G.; Xu, L. Urban-Rural Disparities in Health Care Utilization among Chinese Adults from 1993 to 2011. BMC Health Services Research 2018, 18, 102. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; MacPhail, F.; Dong, X. The Feminization of Labor and the Time-Use Gender Gap in Rural China. Feminist Economics 2011, 17, 93–124. [CrossRef]

- Altenbuchner, C.; Vogel, S.; Larcher, M. Effects of Organic Farming on the Empowerment of Women: A Case Study on the Perception of Female Farmers in Odisha, India. Women’s Studies International Forum 2017, 64, 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Gong, H. Gender Differences in Pesticide Use Knowledge, Risk Awareness and Practices in Chinese Farmers. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 590–591, 22–28. [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, S.I.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Osei-Asare, Y.B. Gender Dimension of Vulnerability to Climate Change and Variability: Empirical Evidence of Smallholder Farming Households in Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2018, 11, 195–214. [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China China Statistical Yearbook 2019 Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Mu, R.; van de Walle, D. Left behind to Farm? Women’s Labor Re-Allocation in Rural China. Labour Economics 2011, 18, S83–S97. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, S.; Rizzo, J.A. The Expansion of Public Health Insurance and the Demand for Private Health Insurance in Rural China. China Economic Review 2011, 22, 28–41. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press, 2001; ISBN 978-0-19-102724-6.

- Chen, S.; Oliva, P.; Zhang, P. Air Pollution and Mental Health: Evidence from China 2018.

- Sankoh, A.I.; Whittle, R.; Semple, K.T.; Jones, K.C.; Sweetman, A.J. An Assessment of the Impacts of Pesticide Use on the Environment and Health of Rice Farmers in Sierra Leone. Environment International 2016, 94, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Cropper, M.L. Measuring the Benefits from Reduced Morbidity. The American Economic Review 1981, 71, 235–240.

- Gerking, S.; Stanley, L.R. An Economic Analysis of Air Pollution and Health: The Case of St. Louis. The Review of Economics and Statistics 1986, 68, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz, A.A. The Demand for Health and Health Concerns after 30 Years. Journal of Health Economics 2004, 23, 663–671. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, D. Exposure to Outdoor Air Pollution and Its Human Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216550. [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8.

- Hu, B.; Shao, S.; Ni, H.; Fu, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Min, X.; She, S.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; et al. Current Status, Spatial Features, Health Risks, and Potential Driving Factors of Soil Heavy Metal Pollution in China at Province Level. Environmental Pollution 2020, 266, 114961. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, W.; Hou, Z.; He, L.; Ma, X.; Meng, Q. Increased Inequalities in Health Resource and Access to Health Care in Rural China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 49. [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Hsiao, W.C. Non-Evidence-Based Policy: How Effective Is China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Reducing Medical Impoverishment? Social Science & Medicine 2009, 68, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sleigh, A.C.; Carmichael, G.A.; Jackson, S. Health Payment-Induced Poverty under China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Rural Shandong. Health Policy and Planning 2010, 25, 419–426. [CrossRef]

- Babiarz, K.S.; Miller, G.; Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Rozelle, S. New Evidence on the Impact of China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme and Its Implications for Rural Primary Healthcare: Multivariate Difference-in-Difference Analysis. BMJ 2010, 341, c5617. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, J.M. Local Health and Social Services Expenditures: An Empirical Typology of Local Government Spending. Preventive Medicine 2017, 105, 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Luechinger, S. Air Pollution and Infant Mortality: A Natural Experiment from Power Plant Desulfurization. Journal of Health Economics 2014, 37, 219–231. [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, N.; Junger, W.L.; Romieu, I.; Cifuentes, L.A.; de Leon, A.P.; Vera, J.; Strappa, V.; Hurtado-Díaz, M.; Miranda-Soberanis, V.; Rojas-Bracho, L.; et al. Effects of Air Pollution on Infant and Children Respiratory Mortality in Four Large Latin-American Cities. Environmental Pollution 2018, 232, 385–391. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Rameezdeen, R.; Hagger, M.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, Z. Dust Pollution Control on Construction Sites: Awareness and Self-Responsibility of Managers. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 166, 312–320. [CrossRef]

- Okumah, M.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Novo, P. Effects of Awareness on Farmers’ Compliance with Diffuse Pollution Mitigation Measures: A Conditional Process Modelling. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 36–45. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y. Can Self-Governance Tackle the Water Commons? — Causal Evidence of the Effect of Rural Water Pollution Treatment on Farmers’ Health in China. Ecological Economics 2022, 198, 107471. [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Cianconi, P.; Mucci, F.; Foresi, L.; Chiarantini, I.; Della Vecchia, A. Climate Change, Environment Pollution, COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 773, 145182. [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Sheng, J. How Can Environmental Knowledge Transfer into Pro-Environmental Behavior among Chinese Individuals? Environmental Pollution Perception Matters. J Public Health 2018, 26, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.M.C.; Rineetha, T.; Sreeharshika, D.; Jothula, K.Y. Health Care Seeking Behaviour among Rural Women in Telangana: A Cross Sectional Study. J Family Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 4778–4783. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhao, X. Impact of Internet Use on Multi-Dimensional Health: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS 2017 Data. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9.

- Daghagh Yazd, S.; Wheeler, S.A.; Zuo, A. Understanding the Impacts of Water Scarcity and Socio-Economic Demographics on Farmer Mental Health in the Murray-Darling Basin. Ecological Economics 2020, 169, 106564. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, M.S.; Karkada, S.N.; Somayaji, G. Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life among Indian Women in Mining and Agriculture. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.H.; Kendig, H.; He, X. Factors Predicting Health Services Use among Older People in China: An Analysis of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study 2013. BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 63. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Income Inequality, Unequal Health Care Access, and Mortality in China. Population and Development Review 2006, 32, 461–483.

- Bellemare, M.F.; Wichman, C.J. Elasticities and the Inverse Hyperbolic Sine Transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 2020, 82, 50–61. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Bian, F.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y. The Impact of Social Support on the Health of the Rural Elderly in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, N.; Fu, M.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.L.; Guo, J. Relationship Between Risk Perception, Social Support, and Mental Health Among General Chinese Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2021, 14, 1843–1853. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Development of the New Rural Cooperative Medical System in China. China & World Economy 2007, 15, 66–77. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lyu, S.; Dai, Z. The Impacts of Socioeconomic Status and Lifestyle on Health Status of Residents: Evidence from Chinese General Social Survey Data. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 2019, 34, 1097–1108. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, A.; FitzGerald, G.; Si, L.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, D. Who Benefited from the New Rural Cooperative Medical System in China? A Case Study on Anhui Province. BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 195. [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. Econometric Analysis; 8th edition.; Pearson: New York, NY, 2017; ISBN 978-0-13-446136-6.

- Gunn, K.M.; Barrett, A.; Hughes-Barton, D.; Turnbull, D.; Short, C.E.; Brumby, S.; Skaczkowski, G.; Dollman, J. What Farmers Want from Mental Health and Wellbeing-Focused Websites and Online Interventions. Journal of Rural Studies 2021, 86, 298–308. [CrossRef]

- Rivers, D.; Vuong, Q.H. Limited Information Estimators and Exogeneity Tests for Simultaneous Probit Models. Journal of Econometrics 1988, 39, 347–366. [CrossRef]

- Staiger, D.; Stock, J.H. Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments 1994.

- World Health Organization. Body Mass Index (BMI). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/body-mass-index (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- The World Bank. Four Decades of Poverty Reduction in China: Drivers, Insights for the World, and the Way Ahead. 2022; ISBN 978-1-4648-1877-6.

- Sun, J.; Lyu, S. Does Health Insurance Lead to Improvement of Health Status Among Chinese Rural Adults? Evidence From the China Family Panel Studies. Int J Health Serv 2020, 50, 350–359. [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, T.; Qi, X. Can China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical System Improve Farmers’ Subjective Well-Being? Front Public Health 2022, 10, 848539. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fei, Y.; Shen, H.; Xu, B. Gender Difference in Knowledge of Tuberculosis and Associated Health-Care Seeking Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Rural Area of China. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 354. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).