1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

The human hand with its opposable thumb is a unique feature of

Homo sapiens [

1,

2]. The hand is an essential tool to handle and manipulate all types of objects, but also to communicate with other humans or machines. To utilize all these features for medical and technical applications, the measurement of the exact kinematics or at least knowledge of certain gestures of the hand with its high degree of freedom (DoF) gains more and more interest. Therefore, a rising number of wearable electronics – especially as part of e-textile systems – are developed with a promising outlook in market perspective [

3]. Just in the healthcare wearable market, a volume of 46.6 Billion USD is predicted for the year 2025. Additional fields of application like robot control and teleoperation [

4,

5,

6,

7], medicine and rehabilitation [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] or to translate sign language [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] and more (cp. [

21]) increasing that volume.

1.2. Related Work

A broad variety of wearable devices has been developed for the use at the human hand [

3,

21]. Very often the main focus is an active, actoric support of the hand with exoskeleton systems [

8,

9,

10,

12,

13,

22], the provision of haptic feedback [

7] or non-kinematic parameters like the measurement of pressure [

23,

24] or the use of electromyography (EMG) [

9,

11,

25] are examined. Especially for the use of EMG, the wearable has to be extended at least to the lower arm [

25]. For the measurement of kinematic parameters very often vision based systems are used [

20,

26,

27], but with the focus on mobile body-bound systems they are not further investigated for this article. Non-visual acquisition of kinematic parameters of the hand – especially the angle of the finger joints – are done using fibre-optic sensors [

28], Hall effect sensors [

29], inertial measurement units (IMU) [

13,

30,

31,

32,

33] or bending sensors [

34]. To store additional hardware (e.g. actoric components or battery packs) bag packs [

9], belts [

35,

36] or cuffs [

7] are used. Furthermore, smart textiles or sensors [

37,

38] or the use of soft robotic concepts [

9,

12,

22,

35,

36] are discussed in literature.

1.3. Our Contribution

In this study, we propose a modular sensorized glove (SenGlove) to measure kinematic parameters of the hand as main functionality. To reduce the number of measurement parameters, the complexity of the hand is reduced from DoF 23 [

39] to DoF 15 applying biomechanic assumptions and concepts. Anthropometric data of the hand is analyzed to secure the applicability of the SenGlove concept to a broad range of individuals, as well as to introduce a possible sizing system. The use of commercially available components is supposed to reduce cost and to achieve a high proximity to a later product development. The concept of a biomechatronic system [

40] forms the basis for the design process, helps to achieve a high degree of user acceptance and to measure without interference of the future user. Basic concepts of the mechatronic design process [

41] like a domain specific development and modularization are utilized to gain an optimized design and to reach a high flexibility of the system in regard to different applications in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, basic assumptions and requirements for SenGlove as well as elements of the domain specific development following VDI 2206 "Design methodology for mechatronic systems" [

41] are described. Only the final design is shown in detail. Design variants discussed during the development are shown briefly in

Appendix A.

2.1. Basic Assumptions and Requirements/aims of the design

The proposed wearable is supposed to be used unrestricted and autonomously in daily life activities by both women in the 5th percentile and men in the 95th percentile (size adaption of the concept). Donning and doffing shall be done be the user on his own. SenGlove is supposed to measure "absolute" angular information on the finger joints (kinematic measurements) in the first place. In regard to the human perception threshold for angular resolution in the finger joints [

42] the measurement accuracy of SenGlove is demanded to be below 2.5°. Additional measuring parameters are pressure information at the fingertips (contact pressure measurements) as well as general information on the movement of the hand (inertial measurements). SenGlove is not intended to be used while handling objects. Therefore, measured contact pressure at the fingertips is regarded as finger-finger or finger-palm contact. No visual analysis is used.

2.2. Simplified Hand Model

An anatomical model of the human hand has a DoF of 23 [

1,

39]. In order to take a first prototypical approach of a wearable for measuring kinematic data of the human hand, a simplified kinematic model of the hand with a DoF of 15 was applied (see

Figure 1). Fingers were numbered from thumb (I) to pinkie finger (V) (in anatomy defined as Digiti DI to DV). To achieve a reduction of DoF abduction and adduction in the

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of each finger and in the

Carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of finger I are neglected. The model depicts the finger joints as mechanical hinge joints with a DoF of 1. In addition, the CMC joints of finger IV and V are neglected, as they only allow minimal movement [

1,

39]. To further reduce the model’s DoF a constraint based on the anatomy and tendon apparatus of the hand is applied [

1]. It describes the coupling between the flexion and extension movements of the

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) and

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the fingers II to V with the linear equation (

1).

where

refers to the flexion angle of the DIP joint, and

refers to the flexion angle of the PIP joint [

43].

The resulting model is shown in

Figure 1. The coordinate system with the axes

,

and

was defined as a global coordinate system [

43]. It is located in the center of the wrist of the hand model. In addition, each joint axis

has a local coordinate system

, where

j refers to the

jth finger at which the considered joint is located, and

i donates the considered axis of a joint.

2.3. Denavit-Hartenberg Method

The coordinate systems

follow the rules of Denavit-Hartenberg-convention [

43,

44]. With the Denavit-Hartenberg method (DH method) it is possible to determine the relative position and orientation of two neighbouring coordinate systems within a kinematic chain in three-dimensional space with only four instead of the usual six parameters – e.g. used in [

4,

13]. Following parameters (DH parameter) are used for implementation of the DH method [

43,

44]:

joint angle of the joint axis describes the angle of rotation from the axis to the axis around the axis

joint distance describes the translation of the origin of the coordinate system along the axis , so that the distance between the origins of and becomes minimal

link length describes the translation of the origin of the coordinate system along the axis , so that the distance between the origins of and becomes minimal

link twist angle describes the angle of rotation from the axis to the axis around the axis

Figure 2 shows the open kinematic chain of fingers II to V. The kinematic chain of finger I is analogous to the CMC, MCP and

Interphalangeal (IP) joints. The DH parameters of the fingers are shown in

Appendix C.

In order to transform a local coordinate system

into the neighbouring coordinate system

, the homogeneous transformation matrix

, also called Denavit-Hartenberg-matrix, from equation (

2) can be applied [

44]:

This homogeneous transformation matrix

describes the position and orientation of the local coordinate system

at the tip of the finger

j with respect to the base coordinate system

[

44]. The matrix is calculated from the product of all Denavit-Hartenberg-matrices of the kinematic chain according to equation (

3):

2.4. Hand Size Examination

The anthropological parameters of the hand, especially the lengths of the fingers, have been examined to lay out the size of SenGlove. Thereby, it must be taken into account that the dorsal skin at the joints stretches when the fingers are flexed [

43,

45]. The maximum possible length of the fingers and phalanges is relevant for the selection of sensors for the developed sensor concept (see

Section 2.6). For the following investigations and estimations, the middle finger is used as a reference, as it is usually the longest finger of the hand [

46].

Table A1 contains the values of middle finger lengths for women and men for different percentiles as determined by [

46]. Length of the middle finger was measured as the distance from the tip of the finger to the midpoint of MCP joint, with the finger fully extended. The stretching of the skin when the middle finger is bent results in an increase in length

of the skin along the longitudinal axis of the finger, which is decisive for the choice and placement of sensors on the hand [

43,

45]. The anatomy of finger joints shows that the articulating surfaces of a joint have different radii of curvature [

47]. Accordingly, the axis of rotation of the finger joints is not a fixed axis, but a helical axis [

48] that shifts during flexion and extension of the joint. According to [

43], these displacements are negligible compared to the dimensions of the finger. [

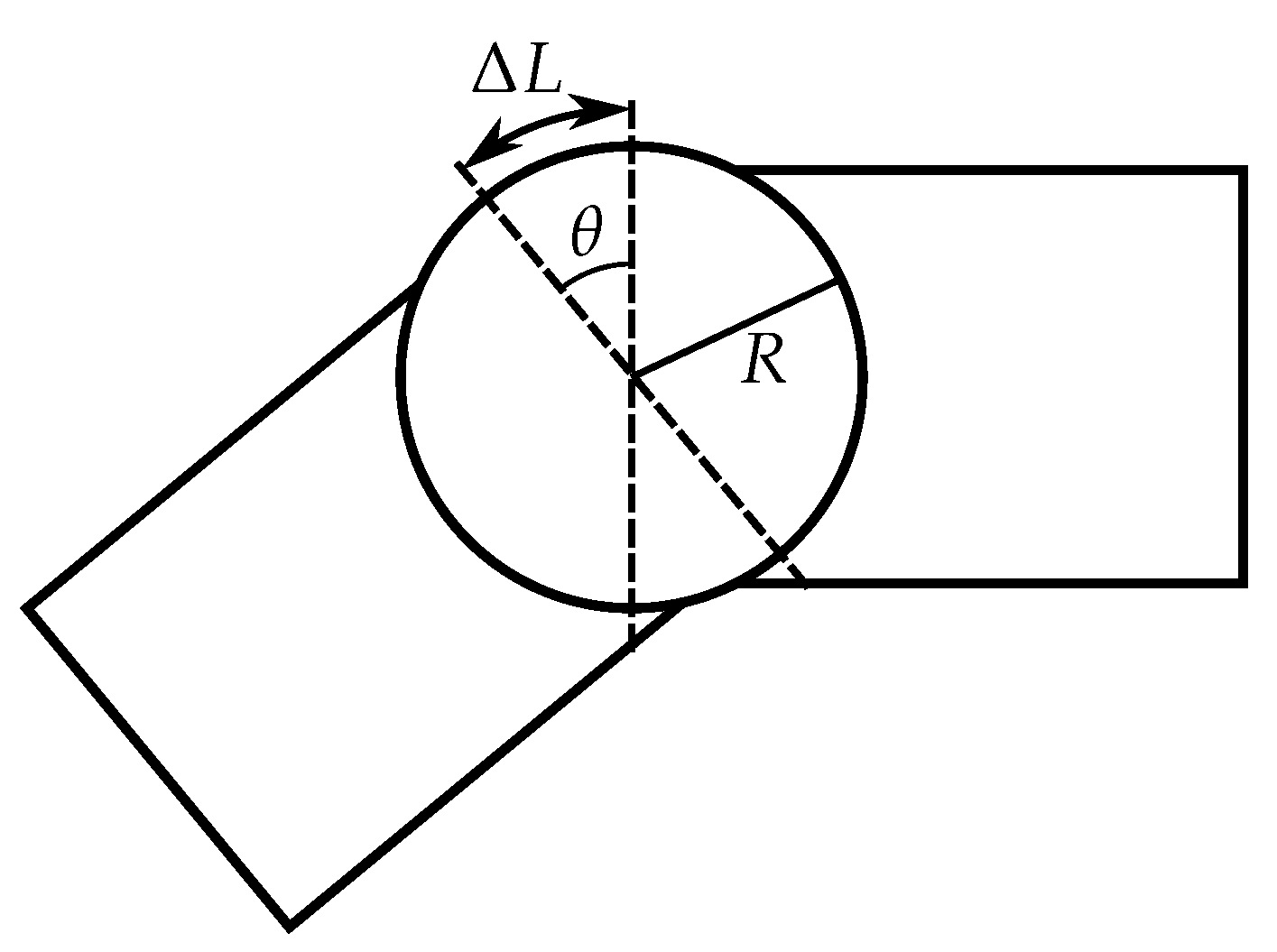

47] determined maximum displacements of the axes of rotation of 1 mm in the MCP joint,

mm in the PIP joint, and

mm in the DIP joint. This allows to assume the axis of the rotation of the finger joints to be stationary, and to model the rotation of the joints by rotating a circular disc of constant radius

R (see

Figure 3).

The increase in length

can be calculated with the deflection angle

, and the radius

R of the joint as the arc length according to equation (

4):

Following equation (

4), the maximum increase in length for the MCP, PIP and DIP joints of a middle finger is calculated for different percentiles in men and women. For

, the angular data of maximum flexion according to [

39] are used (see

Table A2). Radius

R is derived from the anthropometric studies on finger thickness at the location of the joints, according to [

46]. Results are given in

Table A3.

Adding the increase in length

for each joint to the length of the extended middle finger (see

Table A1) gives the length of skin that spans the middle finger when it is flexed actively to the maximum (see

Table A4).

In order to validate the sensor concept chosen, it is necessary to determine the distance between MCP and PIP joint of the middle finger for different percentiles. In the course of literature review for this paper, no study was found which provides absolute values for the lengths of the individual phalanges. Instead, [

49] gives ratios for distances between finger joints.

For the distance

between the centers M of the PIP and MCP joints, and the distance

between the centers M of the DIP and MCP joints, the relationship according to equation

5 applies:

The constant is the averaged ratio between the distances. It has a standard deviation of . For an approximate calculation of the joint distances, the unknown distance is assumed to be the total length of the relaxed finger. This allows the lengths of phalanges to be estimated upwards.

Table A5 presents the calculated results according to equation (

5) for the distance between the PIP and MCP joint, with the middle finger extended. The distance between the PIP and MCP joint with the middle finger flexed was determined by adding the increase in length for both joints from

Table A3. The results are shown in

Table A6.

2.5. Measurement Parameters

Using the proposed model of the hand (see

Figure 1), it is possible to define measurement parameters that the wearable can record and that can be used to describe the kinematics of the hand. They are listed in

Table 1.

Apart from the CMC joint in finger I, flexion and extension angles of all joints considered in the simplified kinematic model may be determined.

In addition, SenGlove can detect contact pressure at all fingertips. While the handling of objects is not intended with SenGlove this information can be used to determine whether the fingertips of individual fingers touch the palm of the hand or the thumb. If contact pressure is detected for all four long fingers, this is evidence that the wearer’s hand has been closed. In case of finger I this means, that the thumb is in opposition position. Angular velocity and linear acceleration are measured in all three axes, each at the back of the hand, to determine the movement of the whole hand.

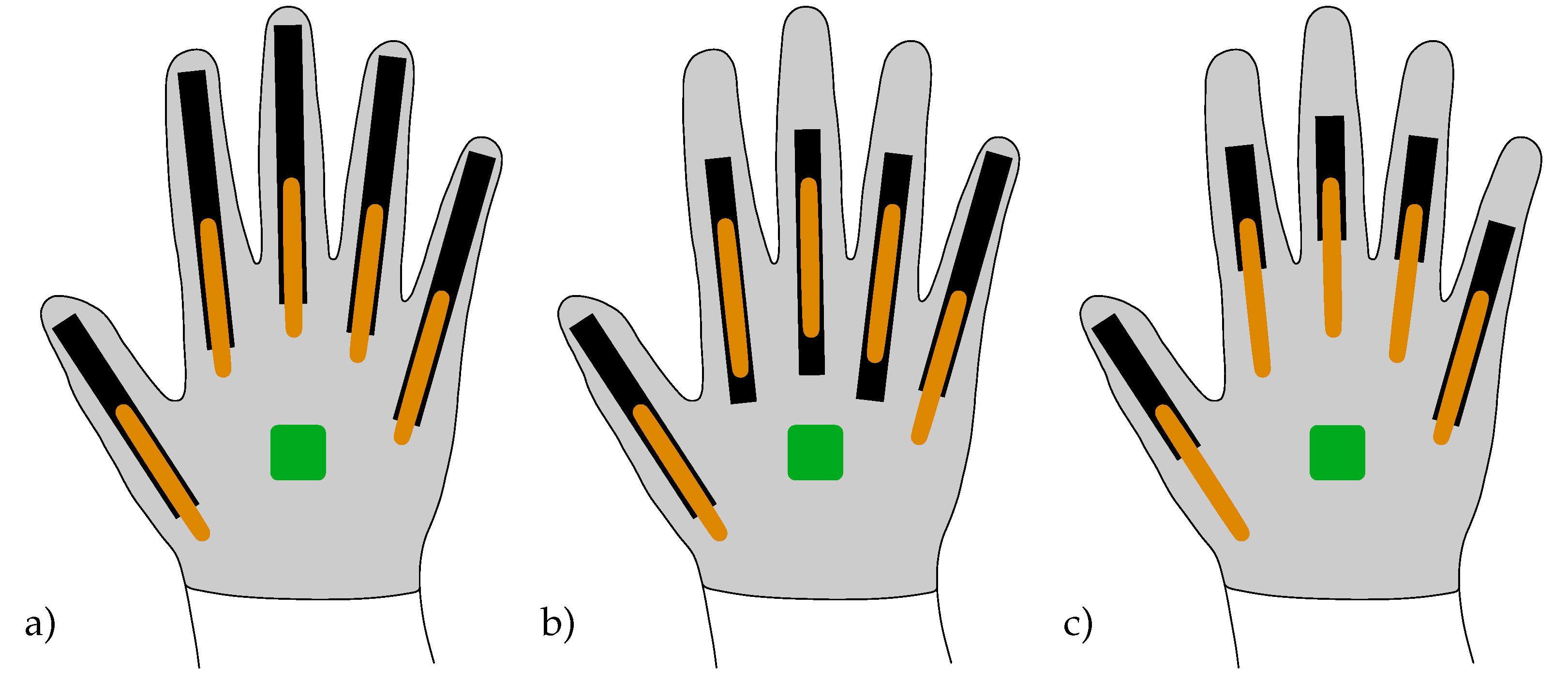

2.6. Sensor concept

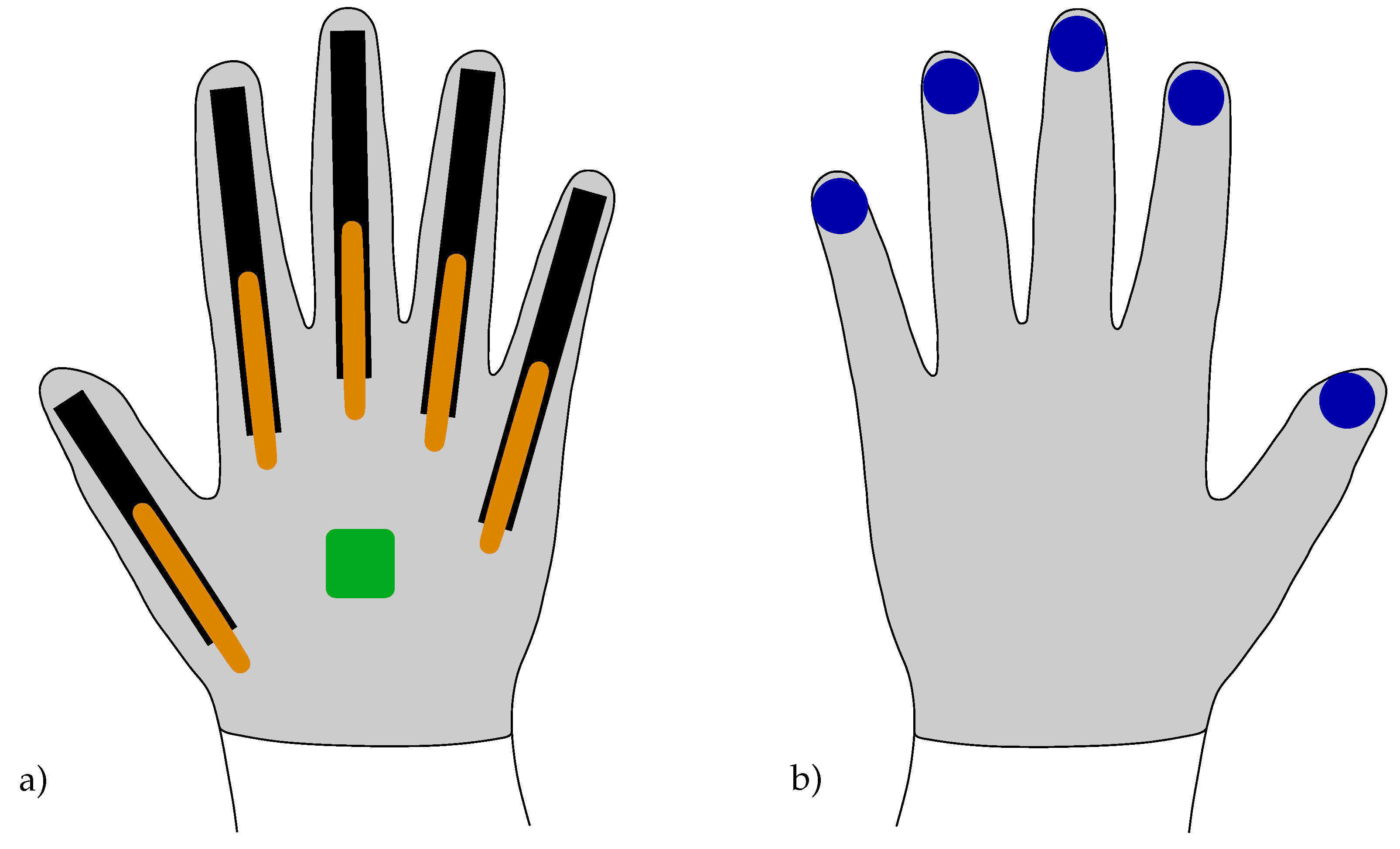

The sensor principle of SenGlove is based on a total of ten flex sensors, five pressure sensors, and one IMU (see

Figure 4). There are five long and five short flex sensors, two sensors for each finger. The long sensors are realized with 1-Axis Soft Flex Sensors from Bend Labs

®, and the short sensors with flex sensors (FS-L-0055-253-ST) from Spectra Symbol

®. Both sensor models are used to measure the flexion and extension angles of the finger joints. The Spectra Symbol

® sensors are placed over each MCP joint. They have an active length of 55 mm, and therefore are long enough to cover the joint for every hand size (see

Table A6). Due to their limited permitted active length of 130 mm, three different position variants of the Bend Labs

® sensors are chosen, depending on the size of the user’s hand (see

Figure A2). The variants consider the increase in length while bending the finger joints and the calculated distances between PIP and MCP joints (see

Table A6). With the linear constraint according to equation (

1) and the two measured angles per finger, flexion and extension angles of each joint of a finger can be determined.

The variant for small-sized hands provides that the Bend Labs

® sensors span the MCP, PIP and DIP joints of the fingers II to V and the MCP and IP joints of finger I (see

Figure A2 a). They measure the combined flexion and extension angles of three and two joints, respectively. This variant even is suitable for women of the first percentile.

In the variant for medium-sized hands, the Bend Labs

® sensors span the MCP and PIP joints of Finger II to V (see

Figure A2 b). This variant fits men up to the 99th percentile. From the fifth percentile for men and the 95th percentile for women, a stretching of the sensors is necessary to compensate for the increase in length.

The variant for large-sized hands is suitable, on the one hand, for wearers whose hands are larger than those of the 99th percentile of men. On the other hand, it offers an alternative for users of the variant for medium-sized hands, where the sensors stretch when the fingers are flexed. With this variant, the Bend Labs™ sensors span the PIP joint of the fingers II to V and the IP joint of finger I (see

Figure A2 c).

Pressure sensors are installed on the wearable’s fingertips to detect the touch of the fingers with the palm and the opposition position of the thumb. The force sensing resistors (FSR) are used as digital switches. Those switches are toggled when the electrical resistance of the sensors has reached a threshold value.

The IMU sensor is mounted on the back of the wearable’s hand to detect the orientation of the user’s hand in space.

2.7. Mechanical structure

For SenGlove, a support structure consisting of a textile glove was selected (cp. design variants in

Appendix A). The chosen glove is a ReliefGrip™ from Bionic Glove Technologies [

50]. The glove chosen is equipped with movement zones made of thin breathable fabric, which are placed above each finger joint, to minimize the restriction of freedom of movement of the fingers (see

Figure 10). A Velcro strap prevents the glove from slipping off the hand (see

Figure 9). The glove is commercially available for both men and women in six different sizes. Each version can be used for the wearable.

Two different attaching methods for the sensors are used. On the one hand, the pressure sensors were put into tubes made of elastic fabric, which were glued directly onto the glove (see

Figure 10). On the other hand, in addition to the elastic tubes, Velcro strips were used for the flex sensors and the IMU sensor (see

Figure 9). All electronic components can be detached from the glove so that it is machine washable.

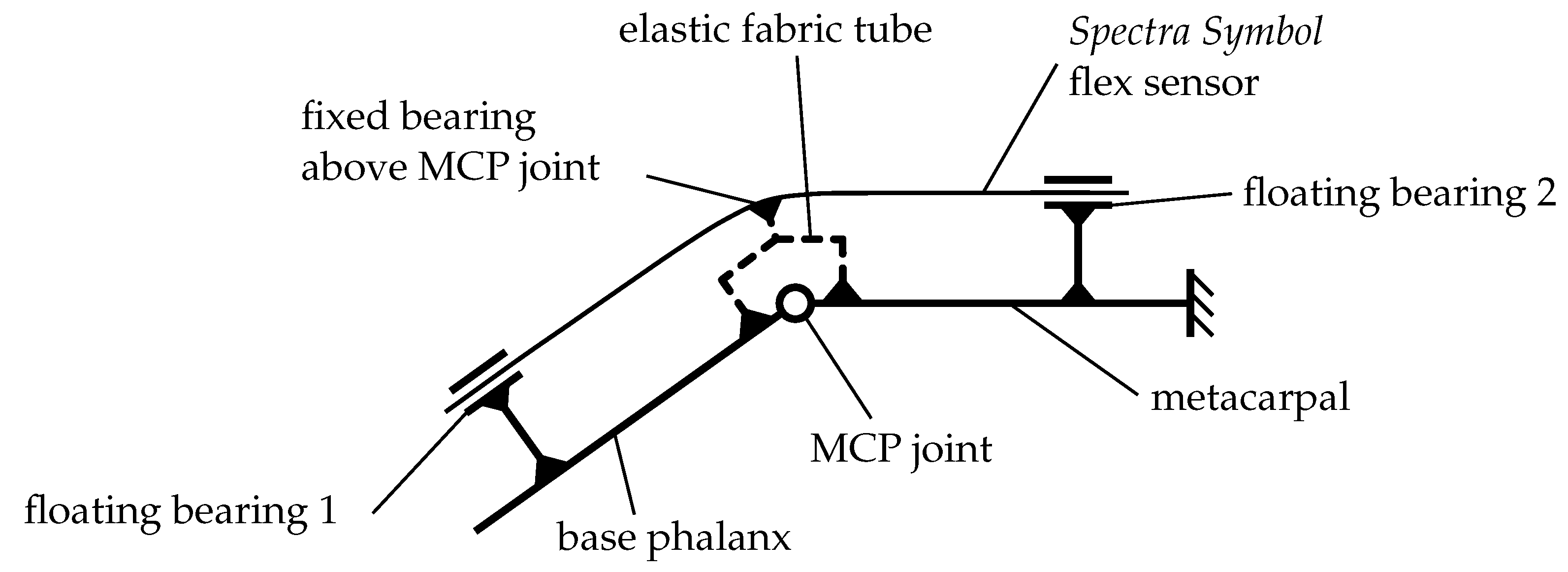

The electrical connectors of the two flex sensors on each finger are stacked on each other. Nevertheless, the mountings of the two sensor types differ. Fixed and floating bearings are used for the Spectra Symbol

® sensor (see

Figure 5). The fixed bearing is located exactly above the MCP joint of a finger. It consists of a tube of elastic fabric glued to the glove. The diameter of the hose is selected in a way that the sensor is clamped in it and can not slide. The position of the fixed bearing guarantees that the axis of rotation of the flex sensor has a constant position above the MCP joint. The sensor is inserted into the fixed bearing in such a way that the bearing is in the center of the sensor. As a result, the bending of the sensor is symmetrical to its center and over the entire active length. The floating bearings of the sensor mounting are located at the sensor ends. They consist of inelastic material, through which the sensor is pushed, and which have no clamping effect. The tube for the distal sensor end is directly glued onto the glove. The tube for the proximal sensor end is fixed with a Velcro strap, so that its position is easily adjustable. Due to the two floating bearings at the ends of the sensor, the sensor can move relatively to the glove when the fingers are bent, compensating for the increase in length

during finger flexion.

No floating bearings are required for the Bend Labs® sensors, as their flexibility allows them to stretch and compress. Fixed bearings made of elastic tubes are used at both sensor ends. The bearings are fixed with Velcro straps. The distal bearing is placed directly on the glove. The proximal bearing is on top of the electrical connector of the Spectra Symbol® sensor. The sensors are placed in such a way that they do not stretch, when the fingers are flexed to the maximum extent. Instead, the sensors are compressed and lift off the fingers in an arc when the fingers are stretched.

For optimized wearing comfort, the components of the wearable with the largest mass are worn proximally on the arm. The Arduino and the battery pack are stowed in a carrying bag that is strapped around the upper arm.

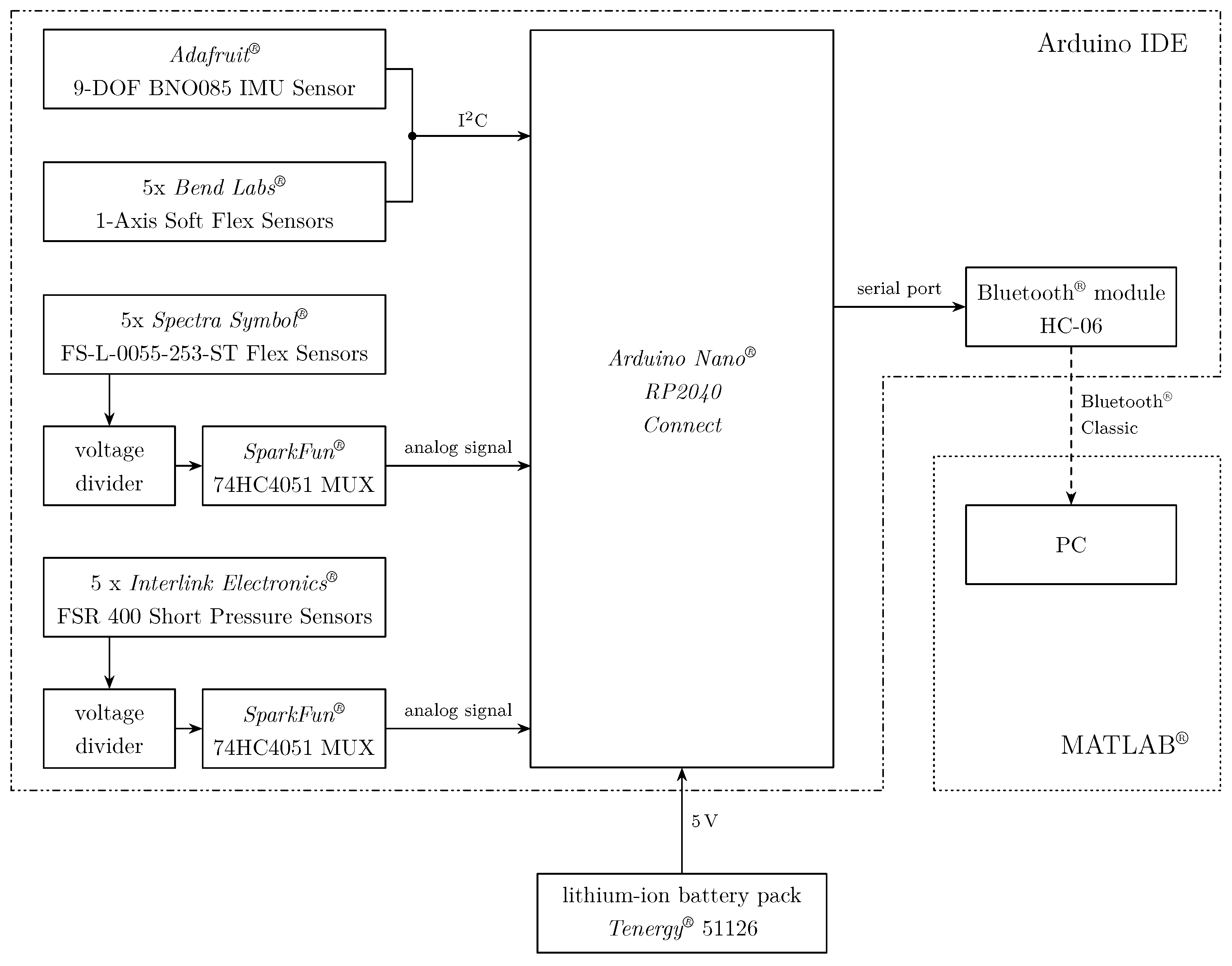

2.8. Electronical structurce

Further electronic components of the proposed wearable are the following:

microcontroller (Arduino Nano® RP2040 Connect)

Bluetooth® module (HC-06)

pressure sensors (Interlink Electronics® FSR 400 Short)

IMU sensor (Adafruit® 9-DOF Orientation IMU BNO085)

low current lithium-ion battery pack (Tenergy® 51126)

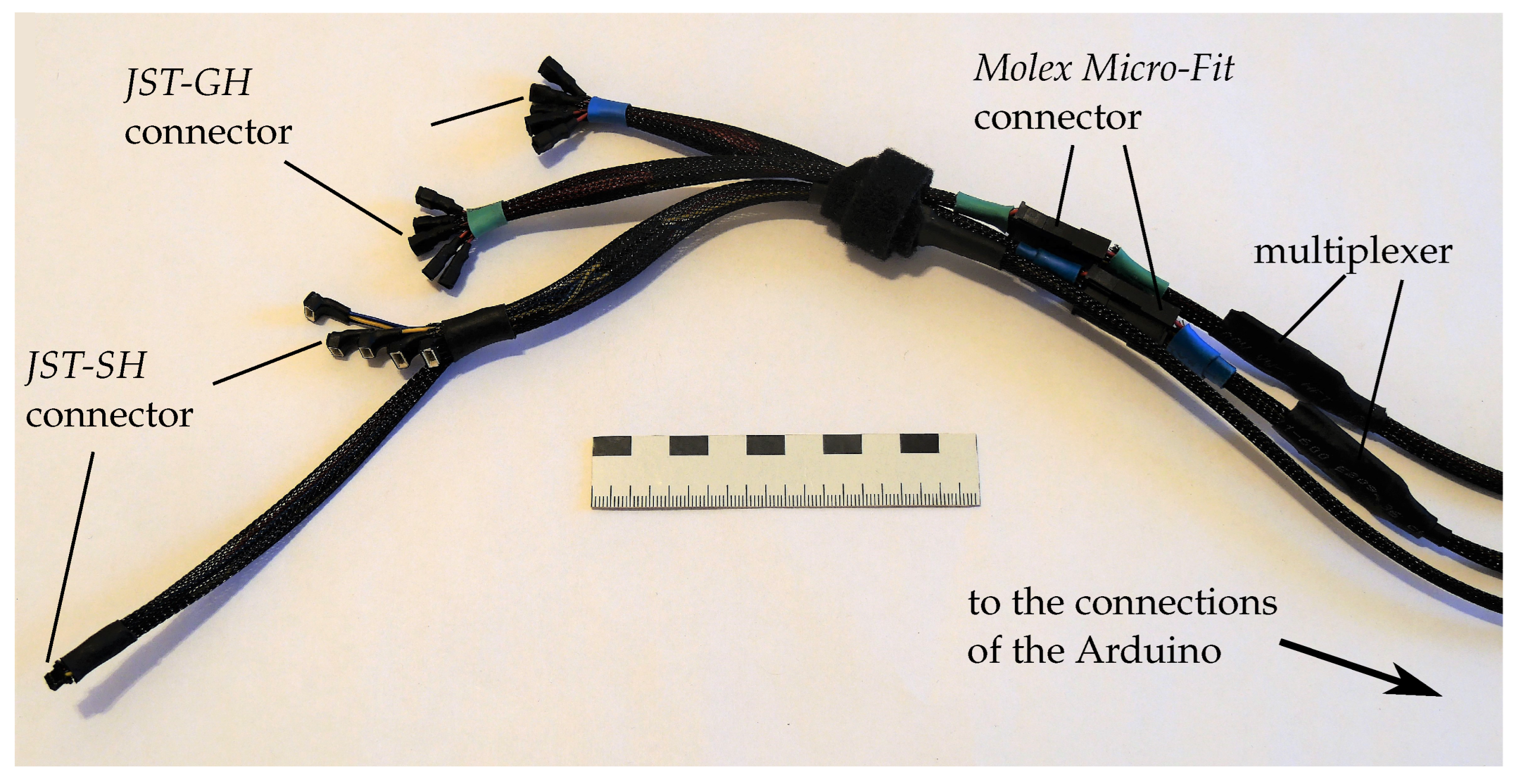

All sensors of SenGlove are connected to the Arduino via a three part wiring harness (see

Figure 6). The Arduino microcontroller is used to read out the sensors and to send their measurement data wirelessly to a personal computer (PC) using an additional Bluetooth

® module. All connections between the electric components are shown in

Figure 7. The Bluetooth

® module uses the Bluetooth

® classic protocol. With this protocol, a higher transmission rate could be achieved compared to the Bluetooth

® Low Energy (BLE) protocol used by the Bluetooth

® module onboard of the Arduino Nano

® RP2040 Connect.

Voltage dividers and the internal analog-digital converter (ADC) of the Arduino are used to read out the analog signals of each Spectra Symbol® sensor and pressure sensor, respectively. Since the Arduino has a total of eight analog inputs, the five bend and pressure sensors can not be connected directly to the Arduino. Therefore, two multiplexers are installed, which are used to read the signals successively via one analog input each.

The Bend Labs™ sensors have a direct interface to a bus, and do not require further electronic components to be read out.

All electronic components of the wearable are powered by a lithium-ion battery pack, which is connected to the USB port of Arduino. The battery pack provides a maximum current of 1 at a voltage of 5 . The Bend Labs® sensors, the IMU sensor and the Arduino work with an operating voltage of . The onboard step-down converter of the Arduino is used to convert 5 to . The Spectra Symbol sensors, the pressure sensors and the corresponding voltage dividers are powered by 5 .

2.9. Software

Two kind of programs are implemented for the wearable. One is an Arduino sketch which is running on the Arduino. The other one is a MATLAB® script which is running on a PC that is connected to the Bluetooth® module.

The Arduino sketch is written with the Arduino IDE (version 1.8.15). The program is used to read the sensors of SenGlove, perform the necessary operations to calculate the angles of each finger joint, and send the data of all sensors to a PC via the Bluetooth

® module. The electronic components associated with each program are marked in

Figure 7.

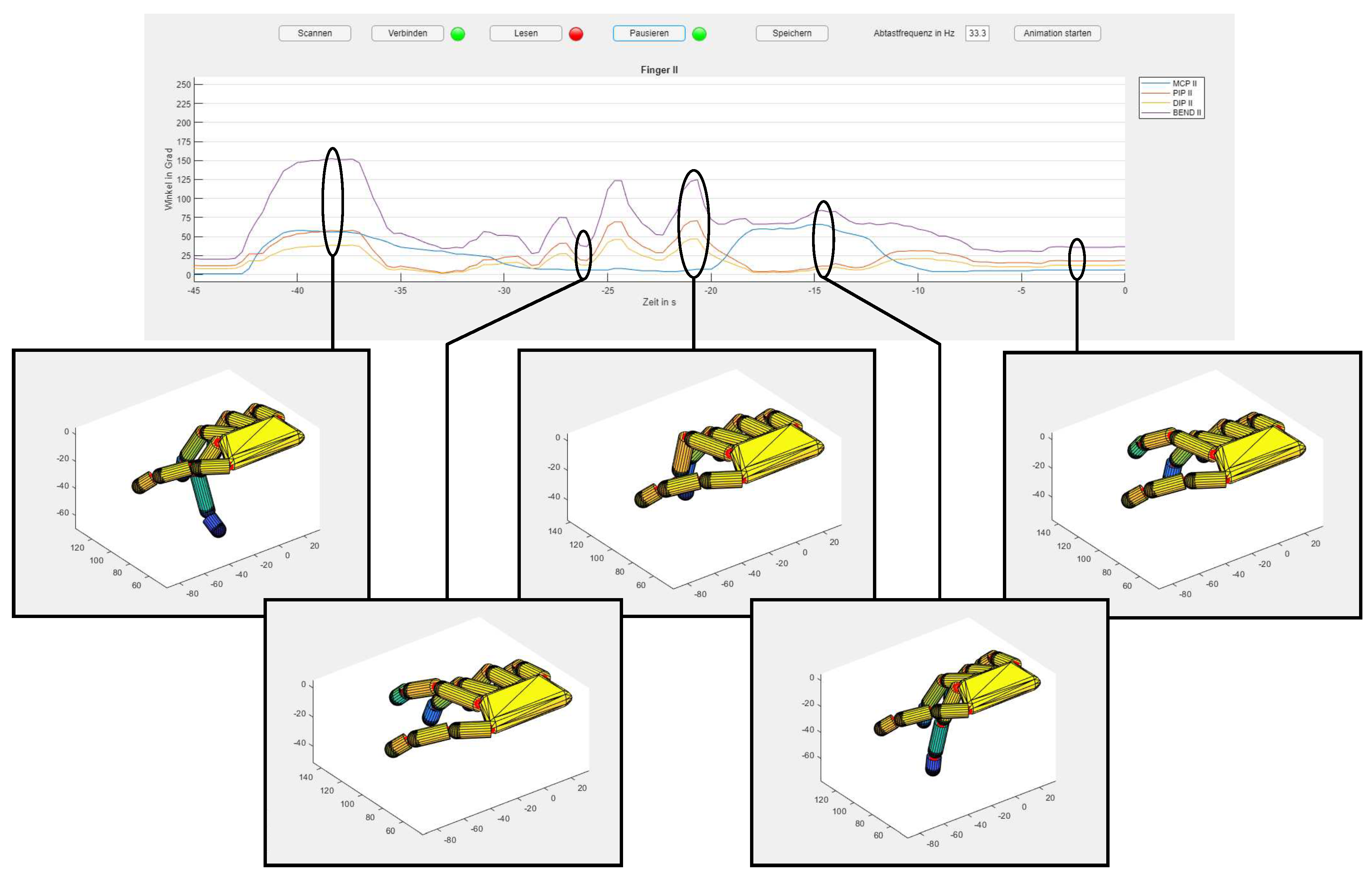

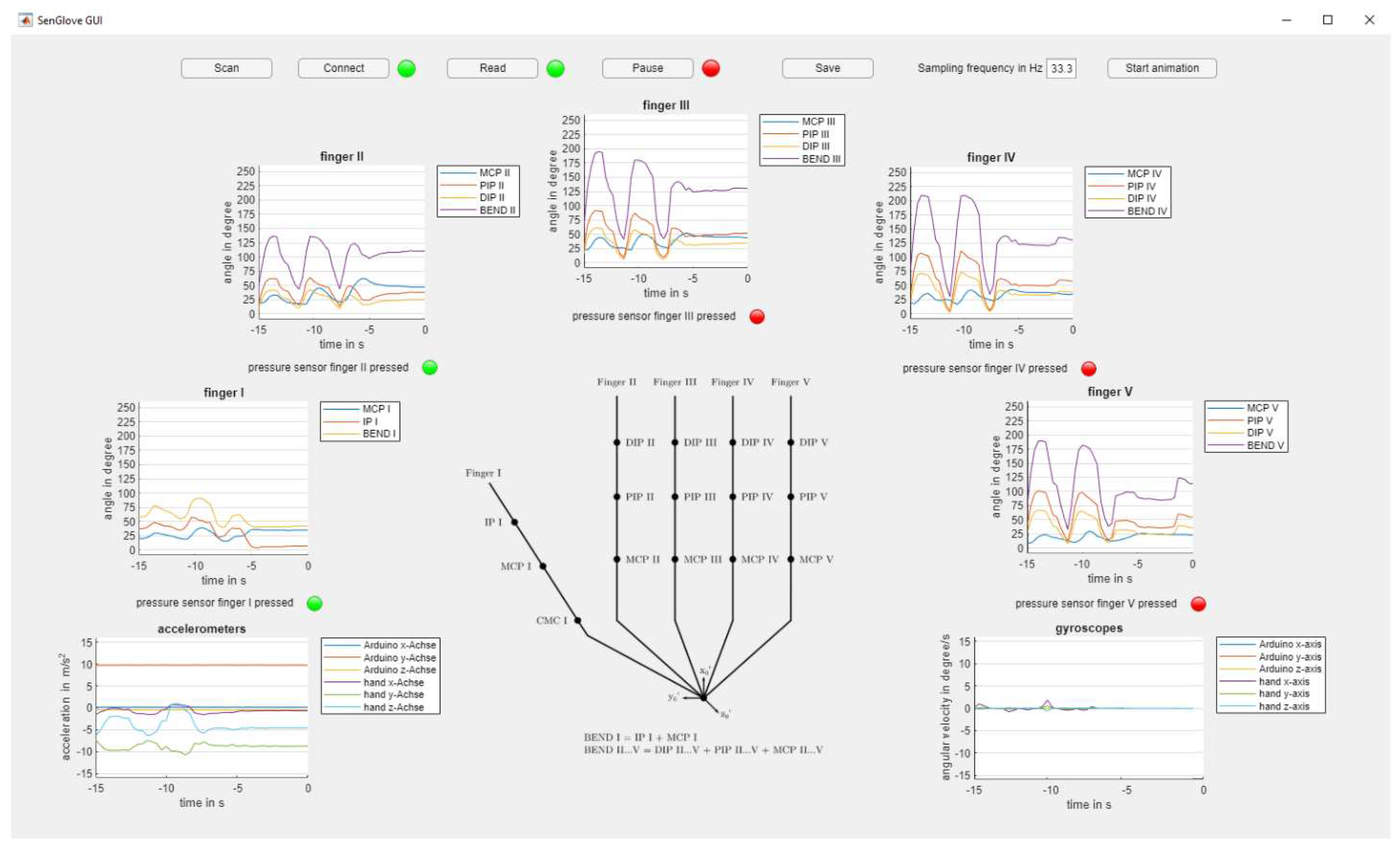

The MATLAB

® script is written with MATLAB

® version R2021a. The script creates a graphical user interface (GUI) through which the collection of the measurement data can be controlled. For each of the five fingers, for the accelerometer and the gyroscope of the IMU there are plots provided in which the corresponding data is displayed. The GUI can also be used to save the data. Besides the plots, there is the option to animate the temporal progression of the angle changes by a 3D model of a hand (see

Figure 14). The MATLAB

® Toolbox

SynGrasp is used to implement the animation [

51].

Measurement accuracy

To validate the measurement accuracy of SenGlove, several measurements were performed with a setup were fingers I to III were sensorized. During the measurements, the wearable was connected to a PC via cable and the USB interface of the Arduino. All angle measurements were performed according to the neutral-zero method [

39].

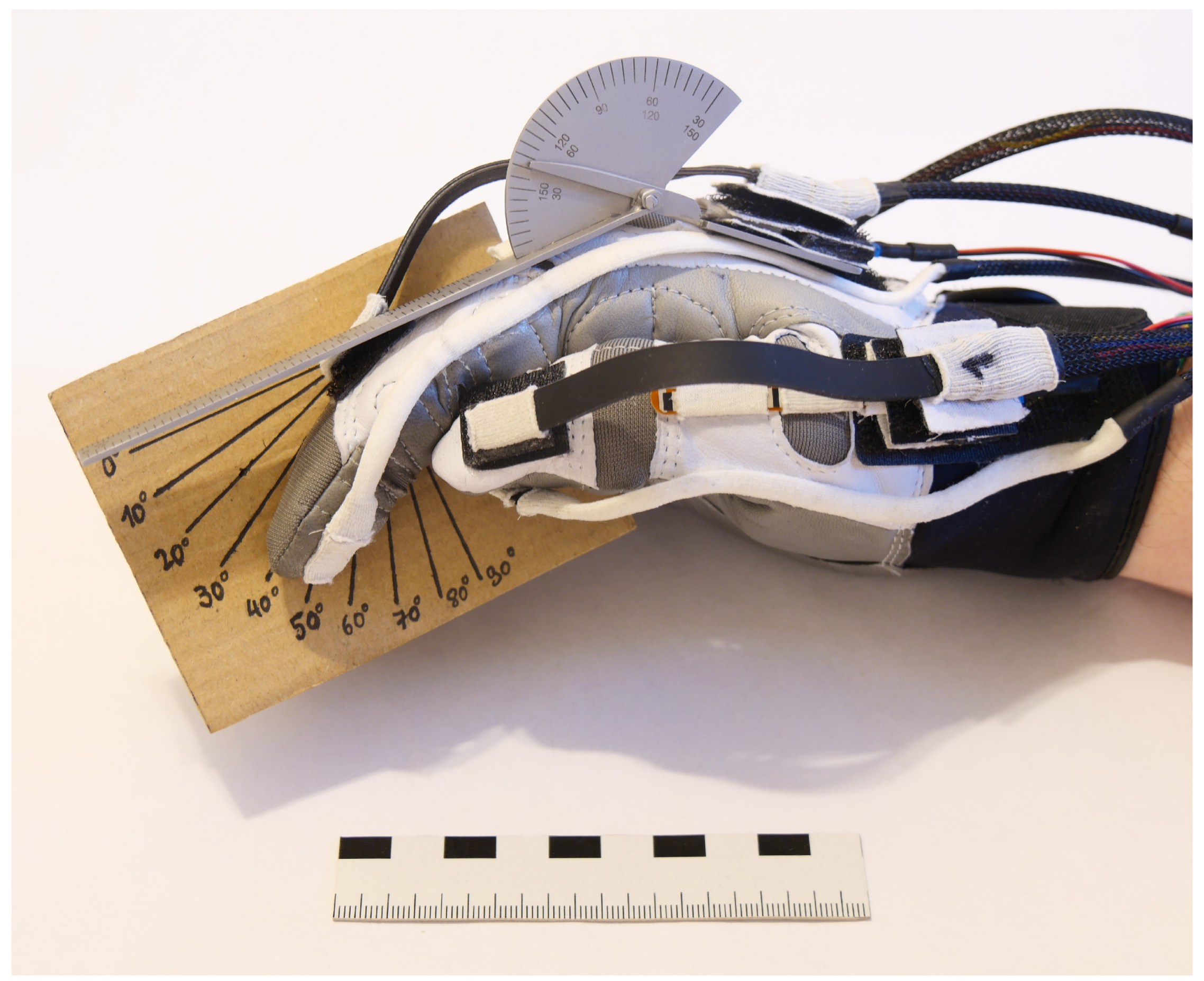

For finger I, the MCP joint of the thumb is flexed at an angle

, which remains unchanged throughout the series of measurements. The value of the angle can assume multiples of ten in a measurement range from 0° to 50°. Subsequently the IP joint is flexed in 10° steps in a range from 0° to 90°. At each step, the wearer keeps the position of his thumb constant while the wearable takes 50 measurements at 100 ms intervals. An analog finger goniometer was used to set the angles (cp.

Figure A3).

For finger II and III the procedure was analogue to finger I. The measuring range for the MCP joint is between 0° and 70° and 0° and 80°, respectively. The angle was increased in 10° steps for each new measurement series. The angle of the PIP joint was increased from 0° to 90° in 10° increments. The angle was initially set with an analog finger goniometer and controlled by an angle template during the measurement (see

Figure A3). To complete the series of measurements, the angle of the DIP joint was measured. Since the DIP and PIP joints are coupled with each other, no angle

was specified for this joint. Instead, the angle of the DIP joint was assumed after

was set, which was directly measured with an analog finger goniometer.

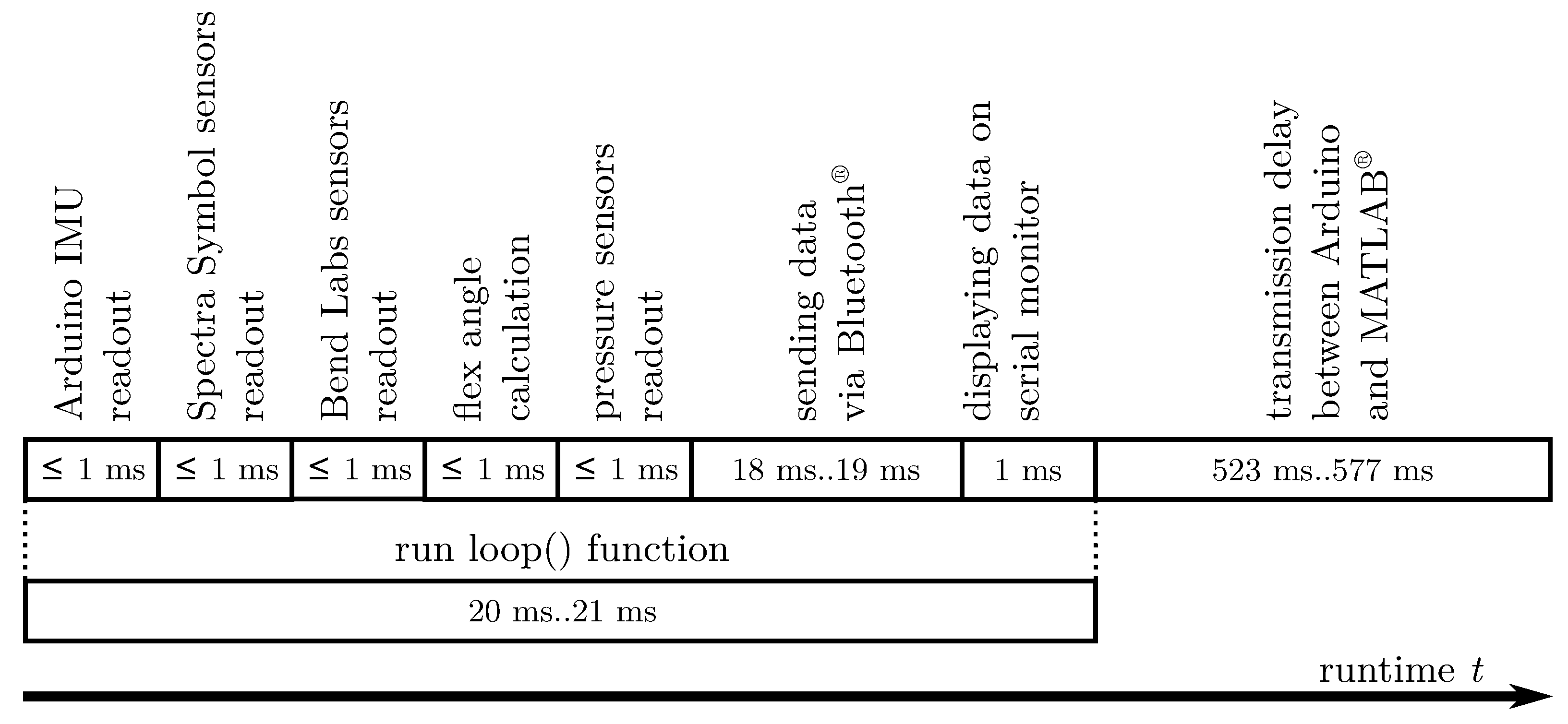

Runtime

Runtime measurements for the Arduino sketch were performed to validate the software. The Arduino was connected with the receiver PC via Bluetooth® Classic and the sensor data sent were received by the MATLAB® script. A transmission confirmation message was implemented in the Arduino sketch to measure transmission delay between the Bluetooth® module and the receiver PC. This message is displayed on the serial monitor when the transmission of a data packet via Bluetooth® is completed. In addition, the MATLAB® script sends a message to the Arduino confirming the receipt of the packet as soon as a data packet has been read out from the serial port. This receipt confirmation is also displayed on the serial monitor. The Arduino will not give out a new sent confirmation until it has received a confirmation of receipt. The time difference between the two messages can be determined with the time stamps of the serial monitor. Transmission delay is half of this time difference, assuming that the transmission of the data packet takes the same time as the transmission of the confirmation.

3. Results

3.1. Final Design

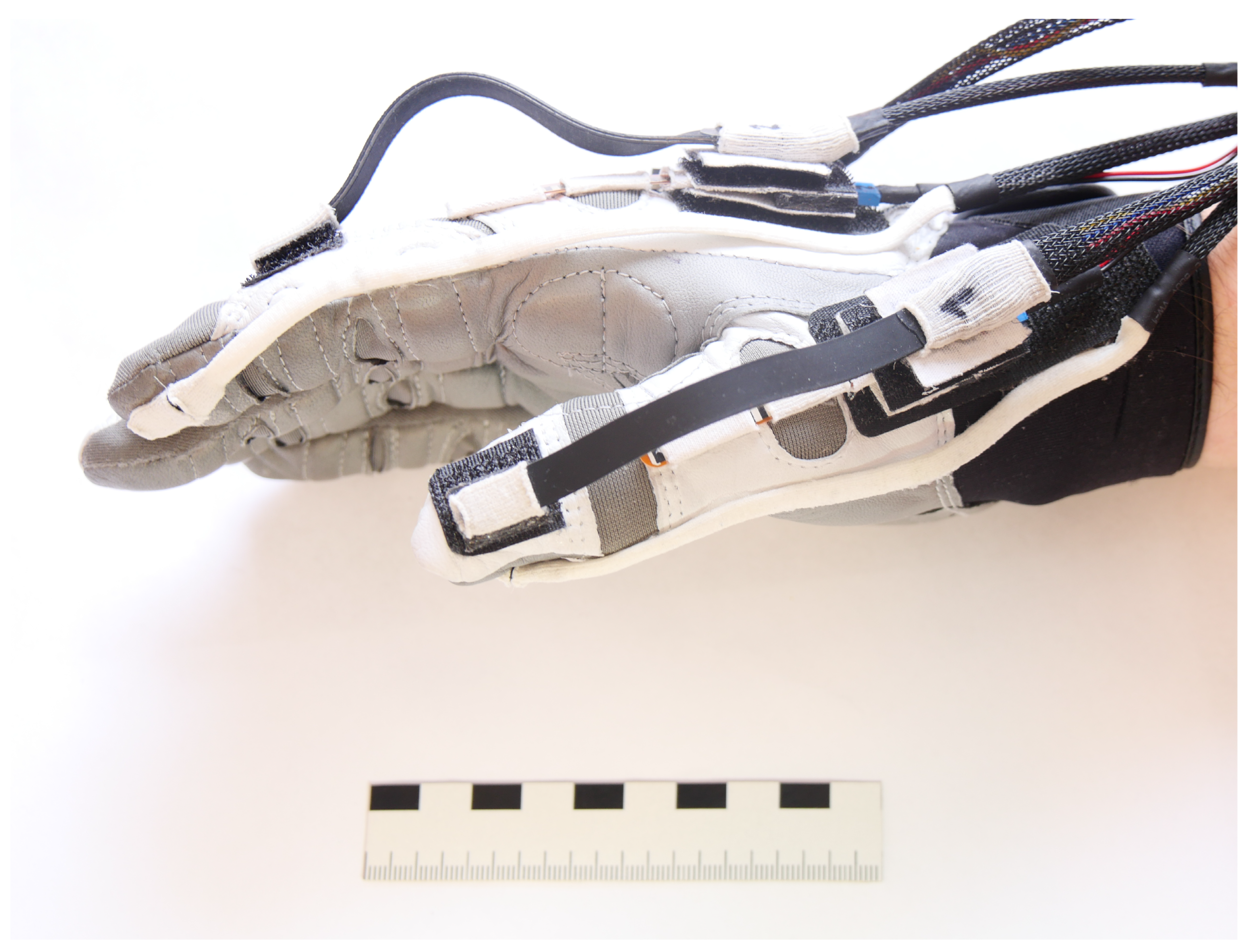

The final design of SenGlove – with sensors for fingers I and II – is shown in

Figure 8 to

Figure 11 for a medium-sized right hand (cp.

Section 2.6 and

Figure A2). It sensorizes the MCP and IP joints of finger I and the MCP, PIP and DIP joints of finger II. It can measure the flexion and extension angles of each of these joints with a maximum root-mean-square error (RMSE) of less than 2.4° - see

Section 3.3. In the full setup of SenGlove (see

Figure A7 to

Figure A9) ten flex sensors, five pressure sensors, and an inertial measurement unit with an accelerometer and a gyroscope are used. Fingers III to V are equipped and regarded analogue to finger II.

All sensors are connected to an Arduino microcontroller. The sensor data is transmitted via Bluetooth

® Classic to a PC, which runs a MATLAB

® Script. It generates a GUI and a plot for each finger, which displays the data as a livestream. The system is modular, so that only the sensors that are required for the specific task need to be installed. The sensors are attached to a glove that acts as a textile support structure. The size of the glove and the position of the sensors can be adjusted depending on the size of the wearer’s hand. The wearable can be fitted to a woman in the 5th percentile and a man in the 95th percentile. Data can be displayed as life plots in a GUI. As alternative to display the data, a 3D animation of the measured hand movement can be generated – see

Section 3.4.

Figure 8.

Overview over SenGlove. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors. Carrier bag used to store the battery pack and the Arduino can be strapped to the upper arm.

Figure 8.

Overview over SenGlove. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors. Carrier bag used to store the battery pack and the Arduino can be strapped to the upper arm.

Figure 9.

SenGlove in dorsal view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure 9.

SenGlove in dorsal view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure 10.

SenGlove in palmar view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure 10.

SenGlove in palmar view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure 11.

SenGlove in lateral view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure 11.

SenGlove in lateral view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with two fingers equipped with sensors.

3.2. Power consumption and mass

SenGlove is powered with 5 , supplied by the battery pack. The maximum current is 30 . Therefore, the power consumption of the wearable is 150 . The battery pack has a capacity of 2500 . Thus, battery life of the wearable is theoretically approximately 83 with a fully charged battery.

Total mass of the SenGlove with all its components is 270 . The highest part of the mass is provided by the components in the carrying bag on the wearer’s upper arm. Together with the surrounding bag, they weigh 177 . The glove with sensors attached but without the wiring harness weighs 58 .

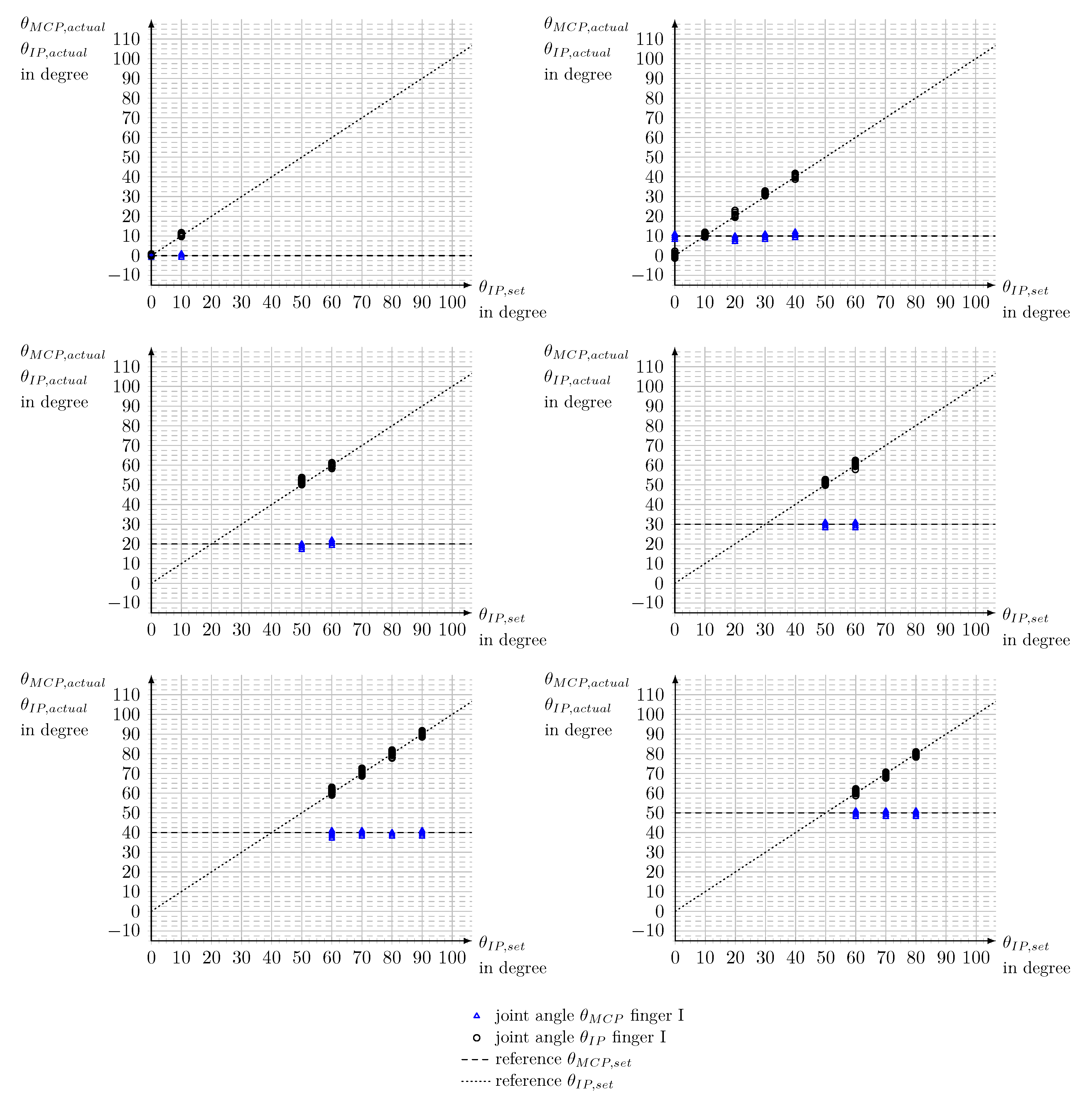

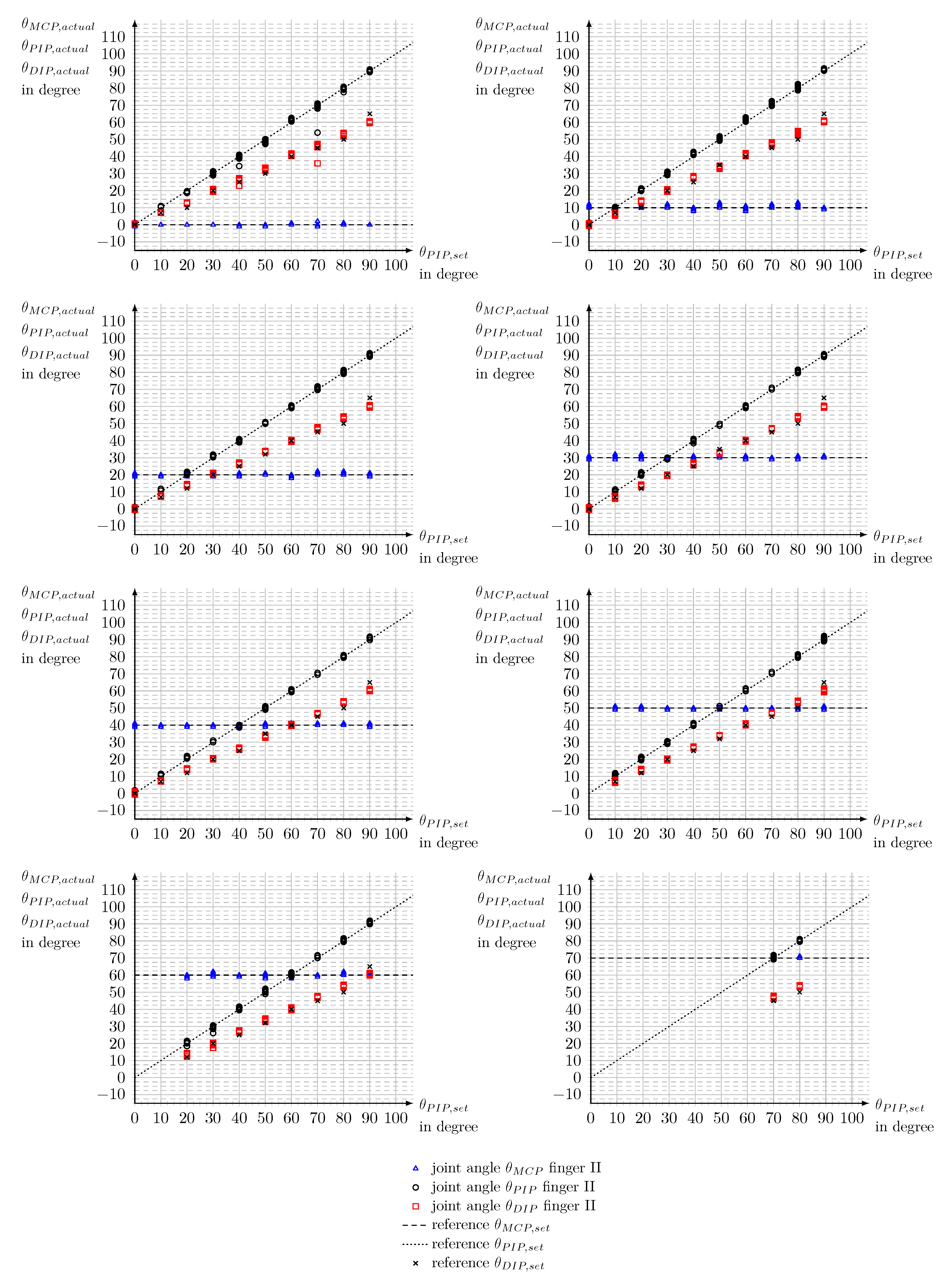

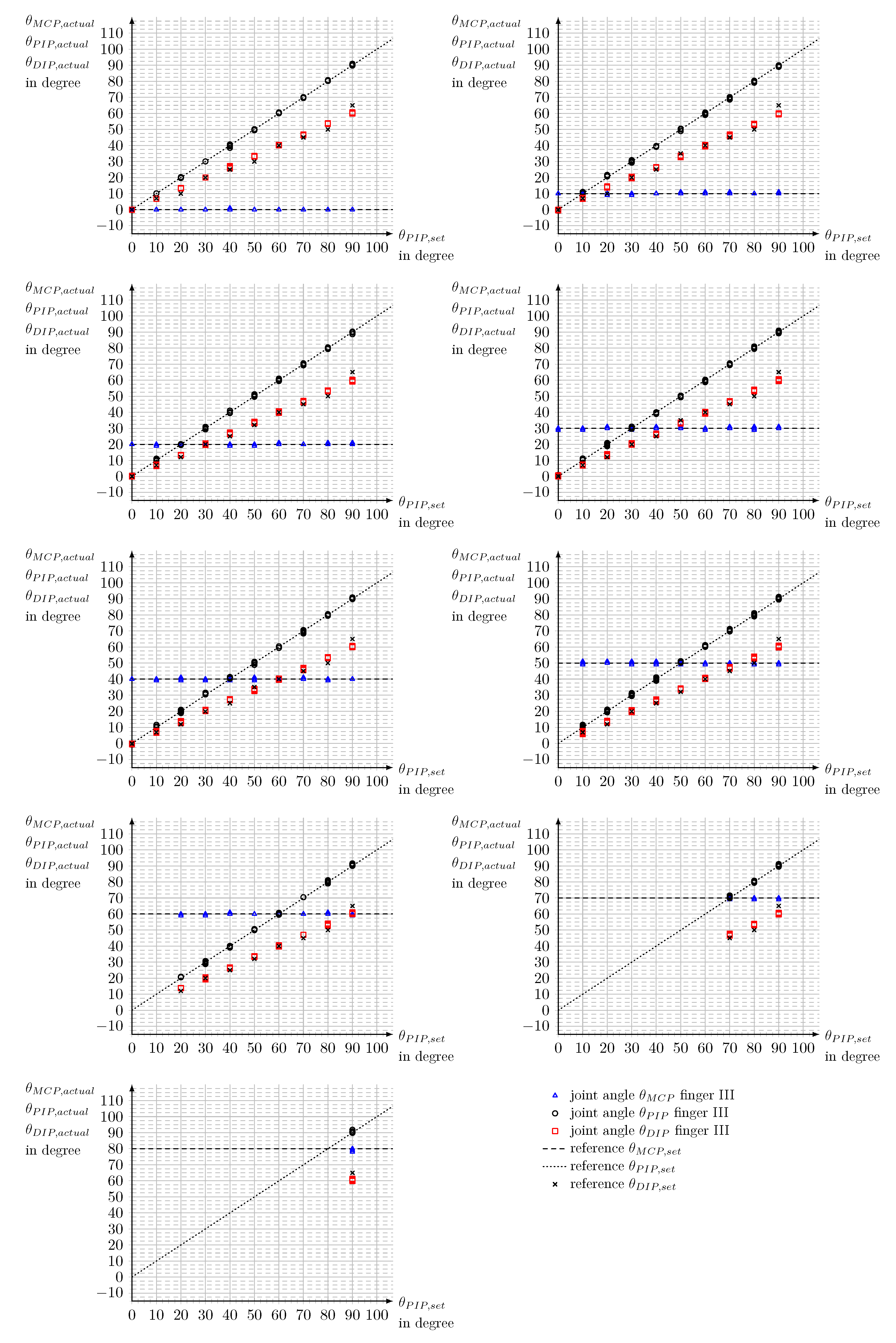

3.3. Measurement accuracy and runtime

The single results for the achieved measurement accuracy are shown in

Appendix E (Finger I),

Appendix F (Finger II) and

Appendix G (Finger III). The reference lines in the plots show the course of the data for an ideal measurement with no measurement deviation. Due to the stiffness of the ReliefGrip™ glove, not all angle combinations could be set while using the wearable. Therefore, the results do not cover the full range of values.

Table 2 illustrates the combined RMSE for finger I to III depending on the joint. Especially for finger I and the MCP and PIP joints of finger II and finger III low RMSE values of less than 1° can be shown. Only the measurements of the DIP joints and thereby the combined value for the MCP, PIP and DIP joint show a higher RMSE with values up to 2.39°.

Figure 12 shows a graphical illustration of the results of the runtime measurements (see

Section 2.10) as a timeline for each sensor read out, sending and displaying the data. All sensors value can be read out and calculate in less than 21 ms per loop. The longest time span of 523 ms to 577 ms appears as a transmission delay between Arduino and MATLAB

®. The achieved run time of 20 ms to 21 ms per loop, results in a sampling frequency of 47

to 50

for SenGlove in general.

3.4. Variants of Visualization

The implemented MATLAB

® script for SemGlove generates a GUI that offers two variants for visualizing the data. While running measurements, the GUI displays the data of the IMU sensor and the flex sensors in seven different live plots (see

Figure 13). The status of the pressure sensor at each fingertip is displayed via a lamp. If a sensor is pressed, the corresponding lamp lights up green, if not, it lights up red. Transmission delay between the Arduino and the PC which is running the MATLAB

® script is less than 600 ms (see

Figure 12). The data of the live plots can be stored for further investigation and visualization.

Based on the measured joint angles, a 3D animation of a moving hand can be generated. It displays the temporal progression of the angle changes in three-dimensional space (see

Figure 14).

4. Discussion

With the presented wearable SenGlove it is possible to measure 14 of 15 angular values of the simplified hand model (cp.

Section 2.2). Additionally, five contact pressures as well as inertial data of the whole hand with a DoF of 6 can be measured. With SenGlove it is possible to determine the angles of all finger joints of the hand digitally and simultaneously. The RMSE achieved for the joint angles on finger I is 0.99°, for finger II 1.53° degrees and for finger III 2.38°. The accuracy for the fingers IV and V are assumed to be comparable to the shown results for finger II and III. The results show that despite the simplifications made, a high measurement accuracy could be achieved. According to [

42], the human perception threshold for the angles of the finger joints is 2.5°. The results show that the wearable’s measurement accuracy for each joint is below this threshold. Accordingly, the wearable is able to measure the angles of the finger joints more accurately than a person can perceive them themselves.

In literature, there are only a few implementations that can measure all finger joints of the hand. Their measurement accuracy varies greatly. Most results are between 2 and 7 degrees [

29,

30,

31,

32,

34]. [

33] achieved the highest angular accuracy with an average error of 0.89. However, this result was only achieved on a mechanical test rig and only for one pair of sensors. The sensor concept was not validated with the designed wearable on a human hand. Compared with the investigated sources, SenGlove demonstrates the highest measurement accuracy for measuring finger joint flexion angles on a non-visual basis in an application without a test rig.

However, the measurement results obtained must be considered in relation to the validation method used. An analog finger goniometer was used, with a measuring scale divided into 5° sections. The basic assumption for the reading uncertainty of a measuring instrument corresponds to half of the smallest scale unit. In the case of the finger goniometer used, angle measurements can be performed with an uncertainty of 2.5° (without taking into account the compliance incoupling the device to the finger which is not to be dicussed here, since no goldstandard does exist). With the designed wearable, measured values can be specified with up to two decimal places. It is not possible with the analog finger goniometer to validate the measurement results of the wearable with certainty.

Since the proposed wearable is intended to be used by many people and only minimal individual adaptation to the wearer should be required, the approximated linear relationship from equation (

1) is used. This constraint condition can only be seen as a simplified approximation. Among others, [

45] investigated the relationship between the joints and was able to show that it can be described more precisely with a second-degree polynomial. Moreover, the coefficients of this polynomial are different for each person and, according to [

45] must be determined individually through experiments.

Figure 14.

Series of screenshots of the 3D animation of a handmodel using the MATLAB

® toolbox SynGrasp [

51]. Finger II has been flexed and extended. Data stream shown in the subplot at the top with angle value (in degree) for the

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP),

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint as well as overall bending of the finger (Bend II).

Figure 14.

Series of screenshots of the 3D animation of a handmodel using the MATLAB

® toolbox SynGrasp [

51]. Finger II has been flexed and extended. Data stream shown in the subplot at the top with angle value (in degree) for the

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP),

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint as well as overall bending of the finger (Bend II).

We proposed a modular design. The textile support structure can be adapted to the hand size of the wearer as well as the position of the sensors. The wearable can be equipped with sensors for any combination of fingers of the hand. This helps to save and adjust costs when not all fingers have to be measured.

Figure A7,

Figure A8 and

Figure A9 show the proposed wearable with sensors for five fingers attached (cp.

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). Furthermore, the results show that the used glove restricts the range of motion of the finger joints, due to the lower deformability of the support structure compared to the human skin.

5. Conclusions

In this contribution we could show, that – although using just commercial available components – (bio-)mechatronic principles can be utilized to create a cost-effective and size adaptable design for a wearable for the human hand with a high measuring accuracy. Despite this fact, SenGlove can only be seen as a technical prototype and functional model so far.

For future technical applications (cp.

Section 1.1) additional developments and optimizations have to be made – e.g. to document rehabilitation progress the range of motion of SenGlove has to be increased by using a more elastic and thinner support structure, for example made of rubber or silicone. To use SenGlove to translate sign language, problems like user acceptance, the number of different languages and the need for large libraries or training have to be addressed [

52]. Thus, the use of SenGlove as an input device for different technical applications, like the programming or control of robots, seems to be closest.

Furthermore, SenGlove can be used as platform for general technical developments or scientific research. E.g. the integration of additional sensor modalities or research on sensor fusion algorithms [

53], deep learning [

20] or different methods to determine specific gestures out of the raw data stream [

54]. It could also be considered to combine the support structure with the sensors and use e-textile technology for the wearable (cp. [

55,

56,

57,

58] or to discuss the integration of actoric components [

13,

24]. Additional challenges for such wearables like washability or the standardization of their development (cp. [

3]) also need to be adressed in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.D., T.H. and H.W.; software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, J.D.; data curation, J.D. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D. and T.H.; writing—review and editing, J.D., T.H. and H.W.; visualization, J.D.; supervision, T.H. and H.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For the technical development no ethical review and approval were obligatory.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Function tests and quantitative validations of the several developments were performed by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dipl.-Ing. Sebastian Köhring for his support during the manufacturing and assembly of SenGlove as well as the help procuring components. Additionally we want to thank neuroConn GmbH, especially Dipl.-Ing. Klaus Schellhorn and Dr.-Ing. Alexander Hunold for the kind exemption of J.D. during his regular labor hours to work on this publication. We acknowledge support for the publication costs by the Open Access Publication Fund of the Technische Universität Ilmenau.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC |

Analog-Digital-Converter |

| BLE |

Bluetooth® Low Energy |

| CMC |

Carpometacarpal |

| DH |

Denavit-Hartenberg |

| DIP |

Distal Interphalangeal |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| DoF |

Degree of Freedom |

| FSR |

Force Sensing Resistor |

| GUI |

Graphical User Interface |

| IDE |

Integrated Development Environment |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IP |

Interphalangeal |

| MCP |

Metacarpophalangeal |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MUX |

Multiplexer |

| PC |

Personal Computer |

| PIP |

Proximal Interphalangeal |

| USB |

Universal Serial Bus |

| VDI |

Verein Deutscher Ingenieure |

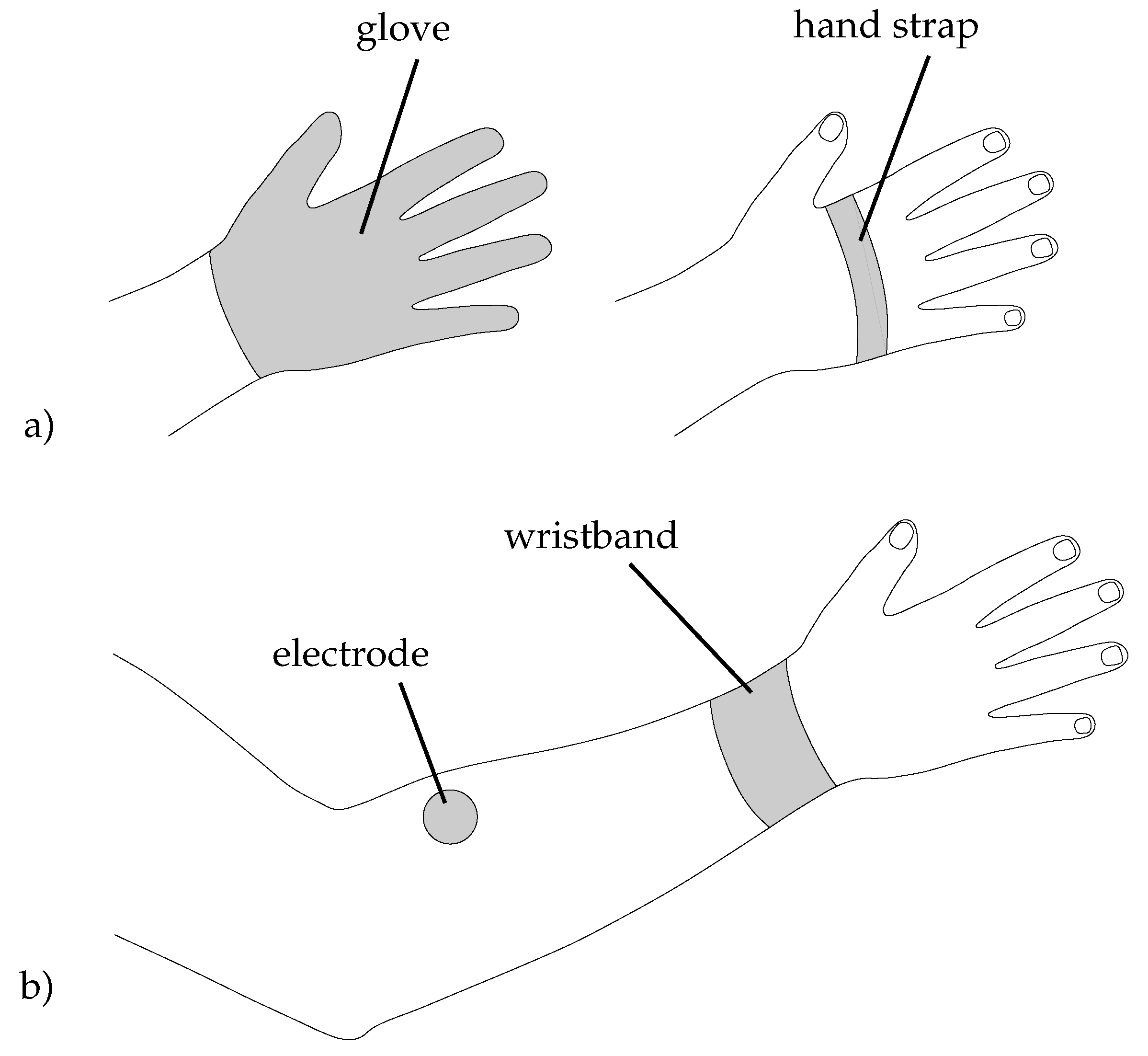

Appendix A — Design Variants

Figure A1.

Types of wearables for the human hand or lower arm in dorsal view. Mechanical support structures shown in grey. a) Wearables for the hand. Left: gloves. Right: hand straps. b) Wearables for the lower arm using wrist straps or additional elements, like electrodes for electromyography.

Figure A1.

Types of wearables for the human hand or lower arm in dorsal view. Mechanical support structures shown in grey. a) Wearables for the hand. Left: gloves. Right: hand straps. b) Wearables for the lower arm using wrist straps or additional elements, like electrodes for electromyography.

Figure A2.

Position variants of the flex sensors (black), depending on the size of the user’s hand in dorsal view. Additional elements shown: mechanical support structure (grey), inertial measurement unit (green), bending sensors for the flexion of the Metacarpophalangeal joint (orange). a) Variant for small-sized hands b) Variant for medium-sized hands c) Variant for large-sized hands

Figure A2.

Position variants of the flex sensors (black), depending on the size of the user’s hand in dorsal view. Additional elements shown: mechanical support structure (grey), inertial measurement unit (green), bending sensors for the flexion of the Metacarpophalangeal joint (orange). a) Variant for small-sized hands b) Variant for medium-sized hands c) Variant for large-sized hands

Appendix B — Finger Anthropometry

Table A1.

Finger length of extended middle finger for men and women according to [

46].

Table A1.

Finger length of extended middle finger for men and women according to [

46].

| |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| men |

102.0 mm |

105.0 mm |

114.0 mm |

123.0 mm |

127.0 mm |

| women |

89.0 mm |

92.0 mm |

101.0 mm |

110.0 mm |

114.0 mm |

Table A2.

Range of motion of the

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP),

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joints according to [

39].

Table A2.

Range of motion of the

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP),

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joints according to [

39].

| Flexion/Extension |

Finger II to V |

| MCP |

90°/0°/45° |

| PIP |

110°/0°/0° |

| DIP |

80°/0°/5° |

Table A3.

Radii of the middle finger joints

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) according to [

46] and resulting increase of skin length over them.

Table A3.

Radii of the middle finger joints

Distal Interphalangeal (DIP),

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and

Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) according to [

46] and resulting increase of skin length over them.

| men |

|---|

| joint radius |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| MCP |

14.0 mm |

14.7 mm |

16.5 mm |

18.3 mm |

19.0 mm |

| PIP |

8.5 mm |

8.9 mm |

10.0 mm |

11.1 mm |

11.5 mm |

| DIP |

6.5 mm |

6.9 mm |

8.0 mm |

9.1 mm |

9.5 mm |

| increase in length |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| MCP |

22.0 mm |

23.1 mm |

25.9 mm |

28.7 mm |

29.8 mm |

| PIP |

16.3 mm |

17.1 mm |

19.2 mm |

21.3 mm |

22.1 mm |

| DIP |

9.1 mm |

9.6 mm |

11.2 mm |

12.7 mm |

13.3 mm |

| women |

| joint radius |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| MCP |

12.0 mm |

12.6 mm |

14.0 mm |

15.4 mm |

16.0 mm |

| PIP |

7.5 mm |

7.8 mm |

8.5 mm |

9.2 mm |

9.5 mm |

| DIP |

5.5 mm |

5.8 mm |

6.5 mm |

7.5 mm |

8.0 mm |

| increase in length |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| MCP |

18.8 mm |

19.8 mm |

22.0 mm |

24.2 mm |

25.1 mm |

| PIP |

14.4 mm |

15.0 mm |

16.3 mm |

17.7 mm |

18.2 mm |

| DIP |

7.7 mm |

8.1 mm |

9.1 mm |

10.1 mm |

11.2 mm |

Table A4.

Total length of skin over the middle finger at maximum flexion.

Table A4.

Total length of skin over the middle finger at maximum flexion.

| |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| men |

149.4 mm |

154.8 mm |

170.3 mm |

185.8 mm |

192.2 mm |

| women |

129.9 mm |

134.9 mm |

148.8 mm |

161.9 mm |

168.5 mm |

Table A5.

Distance between the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint with extended middle finger.

Table A5.

Distance between the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint with extended middle finger.

| |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| men |

59,2 ± 3.6 mm |

60,9 ± 3.7 mm |

66,1 ± 4.0 mm |

71,3 ± 4.3 mm |

73,7 ± 4.5 mm |

| women |

51,6 ± 3.1 mm |

53,4 ± 3.2 mm |

58,6 ± 3.5 mm |

63,8 ± 3.9 mm |

66,1 ± 4.0 mm |

Table A6.

Distance between the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint with flexed middle finger.

Table A6.

Distance between the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint with flexed middle finger.

| |

1st percentile |

5th percentile |

50th percentile |

95th percentile |

99th percentile |

| men |

97,5 ± 3.6 mm |

101,1 ± 3.7 mm |

111,2 ± 4.0 mm |

121,3 ± 4.3 mm |

125,6 ± 4.5 mm |

| women |

84,8 ± 3.1 mm |

88,2 ± 3.2 mm |

96,9 ± 3.5 mm |

105,7 ± 3.9 mm |

109,4 ± 4.0 mm |

Appendix C — Denavit-Hartenberg-Parameters

Table A7.

Denavit-Hartenberg-parameters for fingers I to V according to the newly introduced simplified hand model. Joint angle , joint distance , link length and link twist angle for joint axis with finger number j and joint number i.

Table A7.

Denavit-Hartenberg-parameters for fingers I to V according to the newly introduced simplified hand model. Joint angle , joint distance , link length and link twist angle for joint axis with finger number j and joint number i.

| joint

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

|

0 |

|

0 |

Appendix D — Validation Setup

Figure A3.

Validation setup for SenGlove. Using an analog finger goniometer, the target angles and were set at the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the finger and kept constant during a series of measurements. In this figure a measurement for finger II with , is shown. Compliance with these angles was checked using the finger goniometer and an angle template. After completion of the validation measurement, the angle of the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint was measured with the finger goniometer, which was set due to the coupling to the PIP joint.

Figure A3.

Validation setup for SenGlove. Using an analog finger goniometer, the target angles and were set at the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the finger and kept constant during a series of measurements. In this figure a measurement for finger II with , is shown. Compliance with these angles was checked using the finger goniometer and an angle template. After completion of the validation measurement, the angle of the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint was measured with the finger goniometer, which was set due to the coupling to the PIP joint.

Appendix E — Measurement Accuracy of Finger I

Figure A4.

Accuracy of measurement for finger I. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Interphalangeal (IP) joint . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove.

Figure A4.

Accuracy of measurement for finger I. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Interphalangeal (IP) joint . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove.

Table A8.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger I. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Interphalangeal (IP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP).

Table A8.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger I. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Interphalangeal (IP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP).

| measurement series

|

|---|

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

1° |

1.69° |

1.69° |

|

0° |

-0.31° |

-0.31° |

| RMSE |

0.56° |

0.71° |

0.64° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

2° |

3.01° |

3.01° |

|

-3° |

-1.27° |

-3° |

| RMSE |

0.66° |

1.00° |

0.84° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

2° |

3.79° |

3.79° |

|

-3° |

-1.71° |

-3° |

| RMSE |

1.08° |

1.21° |

1.15° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

1° |

2.76° |

2.76° |

|

-2° |

-2.18° |

-2.18° |

| RMSE |

0.97° |

1.22° |

1.10° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

1° |

3.03° |

3.03° |

|

-3° |

-2.20° |

-2.20° |

| RMSE |

1.19° |

1.10° |

1.14° |

|

measurement series

|

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

1° |

2.23° |

2.23° |

|

-2° |

-2.34° |

-2.34° |

| RMSE |

1.13° |

0.87° |

1.01° |

| measured values of all measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

IP joint |

MCP a. IP joint |

|

2° |

3.79° |

3.79° |

|

-3° |

-2.34° |

-3° |

| RMSE |

0.96° |

1.03° |

0.99° |

Appendix F — Measurement Accuracy of Finger II

Figure A5.

Accuracy of measurement for finger II. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint . Reference for the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint calculated in dependence of . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove. calculated in dependence of .

Figure A5.

Accuracy of measurement for finger II. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint . Reference for the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint calculated in dependence of . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove. calculated in dependence of .

Table A9.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger II. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP).

Table A9.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger II. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP).

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

2° |

2.55° |

3.85° |

3.85° |

|

-1° |

-16.06° |

-5.42° |

-16.06° |

| RMSE |

0.46° |

1.15° |

2.43° |

1.57° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

3° |

2.90° |

4.87° |

4.87° |

|

-2° |

-1.91° |

-4.87° |

-4.87° |

| RMSE |

1.00° |

1.18° |

2.60° |

1.75° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

2° |

1.76° |

4.23° |

4.23° |

|

-2° |

-1.05° |

-5.57° |

-5.57° |

| RMSE |

0.71° |

0.81° |

2.25° |

1.44° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

2° |

1.54° |

4.36° |

4.36° |

|

-1° |

-1.52° |

-5.67° |

-5.67° |

| RMSE |

0.64° |

0.62° |

2.30° |

1.43° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.85° |

3.97° |

3.97° |

|

-1° |

-1.42° |

-5.15° |

-5.15° |

| RMSE |

0.65° |

0.81° |

2.24° |

1.42° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

2.15° |

4.30° |

4.30° |

|

-1° |

-1.00° |

-5.67° |

-5.67° |

| RMSE |

0.57° |

0.71° |

2.36° |

1.46° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

2° |

1.99° |

4.36° |

4.36° |

|

-2° |

-3.93° |

-5.11° |

-5.11° |

| RMSE |

0.89° |

0.92° |

2.49° |

1.62° |

| 5cmeasurement series

|

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.71° |

4.05° |

4.05° |

|

-1° |

-0.77° |

1.16° |

-1° |

| RMSE |

0.61° |

0.55° |

2.79° |

1.68° |

| measured values of all measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

3° |

2.90° |

4.87° |

4.87° |

|

-2° |

-16.06° |

-5.67° |

-16.06° |

| RMSE |

0.72° |

0.90° |

2.39° |

1.53° |

Appendix G - Measurement Accuracy of Finger III

Figure A6.

Accuracy of measurement for finger III. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint . Reference for the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint calculated in dependence of . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove. calculated in dependence of .

Figure A6.

Accuracy of measurement for finger III. Joint angles set for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint from to and for the Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint . Reference for the Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joint calculated in dependence of . Joint angles and measured with SenGlove. calculated in dependence of .

Table A10.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger III. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP).

Table A10.

Results of the measurement series on the measurement accuracy of the joint angles of finger III. Measurement series sorted in dependence of the predetermined angle for the Metacarpophalangeal joint. Results shown are the maximum positiv and negativ deviations, as well as the root-mean-square error (RMSE). Joints: Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP).

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

0.92° |

3.84° |

3.84° |

|

0° |

-1.51° |

-5.13° |

-5.13° |

| RMSE |

0.04° |

1.30° |

2.51° |

1.46° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.65° |

4.44° |

4.44° |

|

-1° |

-1.40° |

-5.68° |

-5.68° |

| RMSE |

0.20° |

0.47° |

2.44° |

1.44° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.23° |

3.63° |

3.63° |

|

-1° |

-1.38° |

-5.92° |

-5.92° |

| RMSE |

0.20° |

0.39° |

2.18° |

1.28° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.20° |

4.02° |

4.02° |

|

-1° |

-1.28° |

-5.52° |

-5.52° |

| RMSE |

0.35° |

0.44° |

2.12° |

1.27° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

2.64° |

3.63° |

3.63° |

|

-1° |

-1.62° |

-5.11° |

-5.11° |

| RMSE |

0.38° |

0.62° |

2.12° |

1.29° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

2.26° |

4.05° |

4.05° |

|

-1° |

-1.31° |

-5.27° |

-5.27° |

| RMSE |

0.50° |

0.68° |

2.19° |

1.36° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

1.55° |

4.05° |

4.05° |

|

-1° |

-1.21° |

-4.99° |

-4.99° |

| RMSE |

0.26° |

0.48° |

2.18° |

1.30° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

0° |

1.74° |

3.85° |

3.85° |

|

-1° |

-0.50° |

-5.28° |

-5.28° |

| RMSE |

0.33° |

0.57° |

2.69° |

1.60° |

| measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

0° |

1.85° |

-3.76° |

1.85° |

|

-2° |

-0.15° |

-5.10° |

-5.10° |

| RMSE |

0.47° |

0.46° |

4.87° |

2.83° |

| measured values of all measurement series |

| parameter |

MCP joint |

PIP joint |

DIP joint |

MCP, PIP a. DIP joint |

|

1° |

2.64° |

4.44° |

4.44° |

|

-2° |

-1.62° |

-5.92° |

-5.92° |

| RMSE |

0.32° |

0.50° |

2.34° |

2.38° |

Appendix H — Fully Sensorized Wearable

Figure A7.

SenGlove in dorsal view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure A7.

SenGlove in dorsal view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure A8.

SenGlove in lateral view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure A8.

SenGlove in lateral view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure A9.

SenGlove in palmar view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

Figure A9.

SenGlove in palmar view. Realization shown for a medium-sized right hand with all five fingers equipped with sensors.

References

- Hirt, B.; Seyhan, H.; Wagner, M.; Zumhasch, R. Anatomie und Biomechanik der Hand; Thieme, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, B.; Collard, M. The Meaning of Homo. Ludus Vitalis 2001, 9, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, S.u.; Tao, X.; Cochrane, C.; Koncar, V. Smart E-Textile Systems: A Review for Healthcare Applications. Electronics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarov, D.; Veneva, I.; Tsveov, M. A New Upper Limb Exoskeleton for Human Interaction with Virtual Enviroments and Rehabilitation Tasks. Engineering 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tawk, C.; in het Panhuis, M.; Spinks, G.M.; Alici, G. Soft Pneumatic Sensing Chambers for Generic and Interactive Human–Machine Interfaces. Advanced Intelligent Systems 2019, 1, 1900002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, M.; Lee, C. Progress in the Triboelectric Human–Machine Interfaces (HMIs)-Moving from Smart Gloves to AI/Haptic Enabled HMI in the 5G/IoT Era. Nanoenergy Advances 2021, 1, 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A.C.; Reid, D.; Ranasinghe, A. A Novel Untethered Hand Wearable with Fine-Grained Cutaneous Haptic Feedback. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Klein, J.; Burdet, E. Robot-assisted rehabilitation of hand function. Current opinion in neurology 2010, 23, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delph, M.A.; Fischer, S.A.; Gauthier, P.W.; Luna, C.H.M.; Clancy, E.A.; Fischer, G.S. A soft robotic exomusculature glove with integrated sEMG sensing for hand rehabilitation. In 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR); 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lambercy, O.; Ranzani, R.; Gassert, R. Chapter 15 - Robot-assisted rehabilitation of hand function. In Rehabilitation Robotics; Colombo, R., Sanguineti, V., Eds.; Academic Press, 2018; pp. 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semprini, M.; Cuppone, A.; Squeri, V.; Konczak, J. Muscle innervation patterns for human wrist control: Useful biofeedback signals for robotic rehabilitation? 2015 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR); 2015; pp. 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, D.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y. Design of Guided Bending Bellows Actuators for Soft Hand Function Rehabilitation Gloves. Actuators 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Chen, X.; Chang, X.; Liu, C.; Guo, L.; Xu, X.; Lv, F.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J. Hand Exoskeleton Design and Human-Machine Interaction Strategies for Rehabilitation. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, K.; Sun, C.; He, Q.; Fan, W.; Fan, E.; Lin, Z.; Tan, X.; Deng, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, J. Sign-to-speech translation using machine-learning-assisted stretchable sensor arrays. Nature Electronics 2020, 3, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allela, R.; Muthoni, C.; Karibe, D. Sign-IO. 2019. Available online: http://www.sign-io.com.

- Chen, X.; Gong, L.; Wei, L.; Yeh, S.C.; Da Xu, L.; Zheng, L.; Zou, Z. A Wearable Hand Rehabilitation System With Soft Gloves. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewska, E.; Kania, M.; Zawiślak, R. Textronic Glove Translating Polish Sign Language. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; Liu, J.; Shimamoto, S. Recognition of Japanese Sign Language by Sensor-Based Data Glove Employing Machine Learning. 2022 IEEE 4th Global Conference on Life Sciences and Technologies (LifeTech); 2022; pp. 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Bae, J. Real-Time Gesture Recognition in the View of Repeating Characteristics of Sign Languages. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 8818–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, S. Vision-based hand gesture recognition using deep learning for the interpretation of sign language. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 182, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipietro, L.; Sabatini, A.M.; Dario, P. A Survey of Glove-Based Systems and Their Applications. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2008, 38, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, O.; Múnera, M.; Moazen, M.; Wurdemann, H.; Cifuentes, C.A. Assessment of Soft Actuators for Hand Exoskeletons: Pleated Textile Actuators and Fiber-Reinforced Silicone Actuators. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Vu, C.C.; Kim, J. Single-Layer Pressure Textile Sensors with Woven Conductive Yarn Circuit. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Asami, Y.; Endo, Y.; Tada, M.; Ogihara, N. Prediction of anatomically and biomechanically feasible precision grip posture of the human hand based on minimization of muscle effort. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardis, D.; Barsotti, M.; Loconsole, C.; Solazzi, M.; Troncossi, M.; Mazzotti, C.; Castelli, V.P.; Procopio, C.; Lamola, G.; Chisari, C.; Bergamasco, M.; Frisoli, A. An EMG-Controlled Robotic Hand Exoskeleton for Bilateral Rehabilitation. IEEE Transactions on Haptics 2015, 8, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, A.; Bebis, G.; Nicolescu, M.; Boyle, R.; Twombly, X. Vision-based hand pose estimation: A review. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2007, 108, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Mustafa, M.B.; Jomhari, N. A Review of the Hand Gesture Recognition System: Current Progress and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157422–157436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, M.; Watanabe, K. Wearable Sensing Glove With Embedded Hetero-Core Fiber-Optic Nerves for Unconstrained Hand Motion Capture. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2009, 58, 3995–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipietro, L.; Sabatini, A.M.; Dario, P. Evaluation of an instrumented glove for hand-movement acquisition. Journal of rehabilitation research and development 2003, 40 2, 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.T.; Chang, J.Y. Sensor Glove Based on Novel Inertial Sensor Fusion Control Algorithm for 3-D Real-Time Hand Gestures Measurements. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 67, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortier, H.G.; Sluiter, V.I.; Roetenberg, D.; Veltink, P.H. Assessment of hand kinematics using inertial and magnetic sensors. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2013, 11, 70–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.S.; Lee, I.J.; Yang, S.Y.; Lo, Y.C.; Lee, J.; Chen, J.L. Design of an Inertial-Sensor-Based Data Glove for Hand Function Evaluation. Sensors 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, P.C.; Yang, S.Y.; Lin, B.S.; Lee, I.J.; Chou, W. Data glove embedded with 9-axis IMU and force sensing sensors for evaluation of hand function. 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 4631–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggio, G.; Bocchetti, S.; Pinto, C.A.; Orengo, G.; Giannini, F. A novel application method for wearable bend sensors. 2009 2nd International Symposium on Applied Sciences in Biomedical and Communication Technologies; 2009; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polygerinos, P.; Wang, Z.; Galloway, K.C.; Wood, R.J.; Walsh, C.J. Soft robotic glove for combined assistance and at-home rehabilitation. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2015, 73, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, H.K.; Ang, B.W.K.; Lim, J.H.; Goh, J.C.H.; Yeow, C.H. A fabric-regulated soft robotic glove with user intent detection using EMG and RFID for hand assistive application. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2016; pp. 3537–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppa, M.; Chiolerio, A. Wearable Electronics and Smart Textiles: A Critical Review. Sensors 2014, 14, 11957–11992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.T.; Shen, C.L.; Tang, C.F.; Chang, S.H. A wearable yarn-based piezo-resistive sensor. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2008, 141, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumüller, G.; Aust, G.; Conrad, A.; Engele, J.; Kirsch, J. Duale Reihe Anatomie; Thieme: Duale Reihe, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, H.; Schilling, C. The concept of biomechatronic systems as a means to support the development of biosensors. International Journal of Biosensors & Bioelectronics 2017, 2, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (VDI), V.D.I. Entwicklungsmethodik für mechatronische Systeme (VDI 2206): Design methodology for mechatronic systems; VDI, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Virtual Reality: Scientific and Technological Challenges; Durlach, N.I., Mavor, A.S., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.J. A Sign-Component-Based Framework for Chinese Sign Language Recognition Using Accelerometer and sEMG Data. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012, 59, 2695–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W. Industrieroboter: Methoden der Steuerung und Regelung; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Lee, J.; Bae, J. Development of a Wearable Sensing Glove for Measuring the Motion of Fingers Using Linear Potentiometers and Flexible Wires. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2015, 11, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, A.; Associates, H. The Measure of Man and Woman: Human Factors in Design Interior design.industrial design. 2002.

- Burfeind, H. Zur Biomechanik des Fingers unter Berücksichtigung der Krümmungsinkongruenz der Gelenkflächen; Cuvillier, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- de Monsabert, B.G.; Visser, J.M.A.; Vigouroux, L.; Van der Helm, F.C.T.; Veeger, H.E.J. Comparison of three local frame definitions for the kinematic analysis of the fingers and the wrist. JOURNAL OF BIOMECHANICS 2014, 47, 2590–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, E.; An, K.; Conney, W.; Linscheid, R. Biomechanics Of The Hand: A Basic Research Study; World Scientific Publishing Company, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bionic Gloves | ReliefGrip™ Golf Gloves. 2021. Available online: https://www.bionicgloves.com/reliefgrip?quantity=1&custcol3=14.

- Malvezzi, M.; Gioioso, G.; Salvietti, G.; Prattichizzo, D. SynGrasp: A MATLAB Toolbox for Underactuated and Compliant Hands. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2015, 22, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. Do deaf communities actually want sign language gloves? Nature Electronics 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, D.; Riener, R. A survey of sensor fusion methods in wearable robotics. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2015, 73, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, E. Articulated Hand Pose Estimation Review. CoRR 2016, abs/1604.06195. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Yang, L.; Gravina, R.; Fortino, G. Soft Wrist-Worn Multi-Functional Sensor Array for Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 17505–17514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, L.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Gu, G.; Shull, P.B. Stretchable e-Skin Patch for Gesture Recognition on the Back of the Hand. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 67, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, S.; Shull, P.B.; Gu, G. SkinGest: artificial skin for gesture recognition via filmy stretchable strain sensors. Advanced Robotics 2018, 32, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, R.; Kadomoto, J.; Shizuki, B. A Sensing Technique for Data Glove Using Conductive Fiber. Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume CHI EA ’19, pp. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Simplified kinematic model of a human hand with a degree of freedom of 15. Fingers numbered I (thumb) to V (pinkie finger). Joints: Carpometacarpal (CMC), Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Interphalangeal (IP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP). Global coordinate system with the axes , and . In anatomical terms: points distal, points radial, points palmar.

Figure 1.

Simplified kinematic model of a human hand with a degree of freedom of 15. Fingers numbered I (thumb) to V (pinkie finger). Joints: Carpometacarpal (CMC), Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Interphalangeal (IP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP). Global coordinate system with the axes , and . In anatomical terms: points distal, points radial, points palmar.

Figure 2.

Open kinematic chain of finger II to V () with the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joints. For better distinction, the axes of the local coordinates of each joint are colored red and the axes are colored blue. The distances correspond to the functional lengths of phalanges of the fingers.

Figure 2.

Open kinematic chain of finger II to V () with the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) and Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joints. For better distinction, the axes of the local coordinates of each joint are colored red and the axes are colored blue. The distances correspond to the functional lengths of phalanges of the fingers.

Figure 3.

Increase in length of the skin over the finger joint due to flexion. Depending on radius of the joint R and deflection angle .

Figure 3.

Increase in length of the skin over the finger joint due to flexion. Depending on radius of the joint R and deflection angle .

Figure 4.

Final sensor concept of SenGlove. Variant shown: small-sized hands with a textile support structure for the hand (grey). a) dorsal view with inertial measurement unit (green), bending sensors for the flexion of an entire finger (black), bending sensors for the flexion of the MCP joint (orange), b) palmar view with pressure sensors (blue).

Figure 4.

Final sensor concept of SenGlove. Variant shown: small-sized hands with a textile support structure for the hand (grey). a) dorsal view with inertial measurement unit (green), bending sensors for the flexion of an entire finger (black), bending sensors for the flexion of the MCP joint (orange), b) palmar view with pressure sensors (blue).

Figure 5.

Principle of sensor mounting for the Spectra Symbol® flex sensor. A mixture of fixed and floating bearings secure a symmetrical bending of the sensor over the joint. Shown for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint.

Figure 5.

Principle of sensor mounting for the Spectra Symbol® flex sensor. A mixture of fixed and floating bearings secure a symmetrical bending of the sensor over the joint. Shown for the Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint.

Figure 6.

Wiring harness of SenGlove.

Figure 6.

Wiring harness of SenGlove.

Figure 7.

Electronic components and signal structure of SenGlove.

Figure 7.

Electronic components and signal structure of SenGlove.

Figure 12.

Timeline with runtime measurement results for the Arduino sketch.

Figure 12.

Timeline with runtime measurement results for the Arduino sketch.

Figure 13.

GUI of the MATLAB® script for SenGlove. Menue at the top to scan for devices (Scan), connect to a device (Connect), start reading data (Read), pause reading data (Pause), store read data (Save), display of the current sampling frequency (Sampling frequency) and to start the 3D animation of the hand (Start animation). In center: Simplified kinematic model of a human hand with a degree of freedom of 15. Fingers numbered I (thumb) to V (pinkie finger). Joints: Carpometacarpal (CMC), Distal Interphalangeal (DIP), Interphalangeal (IP), Metacarpophalangeal (MCP), Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP). Global coordinate system with the axes , and . Subplots (from left to right) for linear acceleration of the hand (accelerometers), angle in degree for Finger I to V with pressure information for each finger underneath (green = threshold exceeded, red = threshold not exceeded), angular velocity of the hand (gyroscopes).

Figure 13.