Submitted:

23 February 2023

Posted:

24 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Cubic Fe3O4 (C-Fe3O4) NP Synthesis.

2.3. Silica and HPG Coating of C-Fe3O4 NPs and Ethylenediamine Coupling

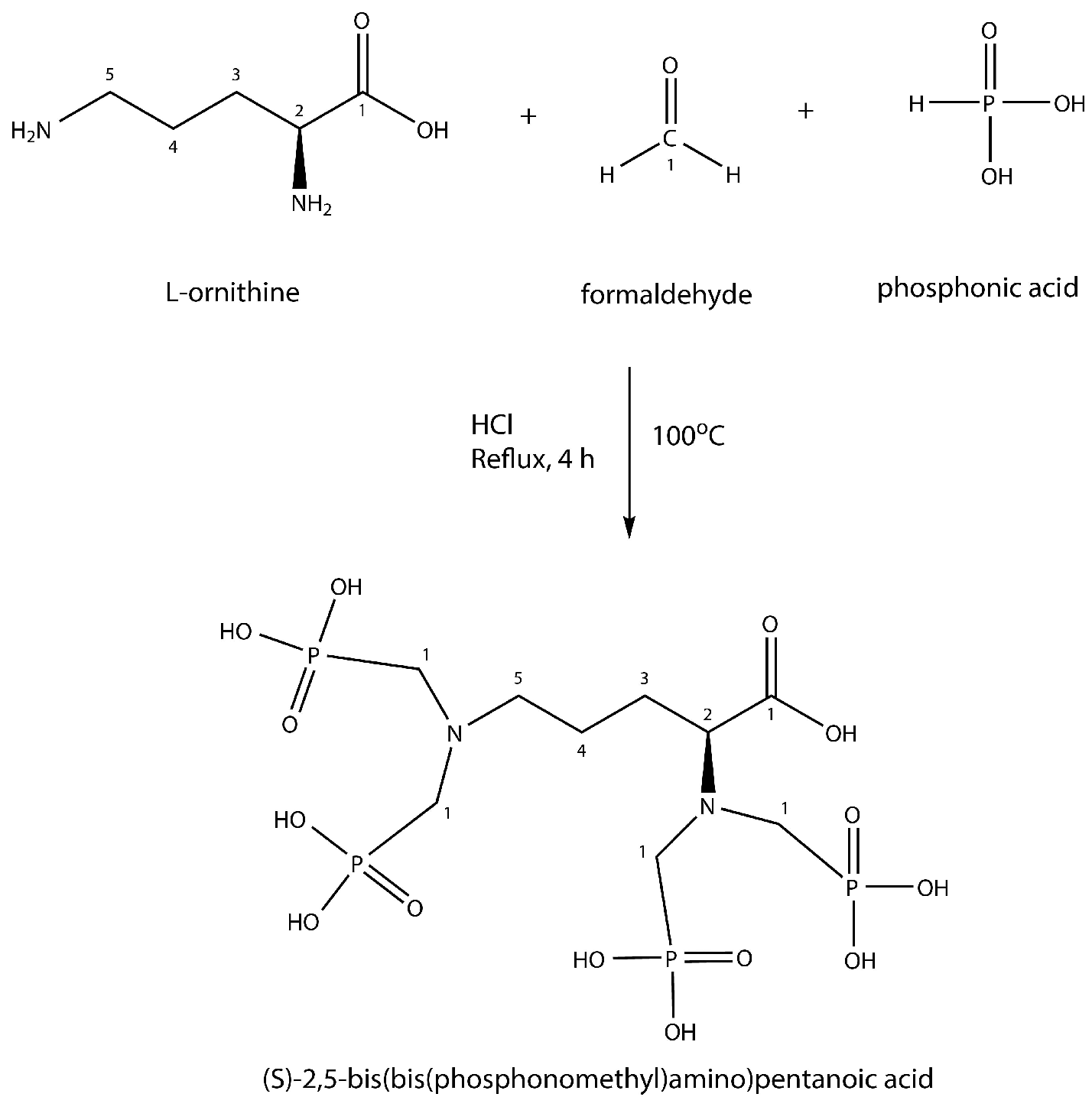

2.4. Synthesis of DPAPA and Conjugation with Fe3O4-SiO2-HPG-NH2

2.5. Production of 44/47Sc

2.6. Separation Procedure

2.7. Radiolabeling with 44/47Sc

2.8. Stability Tests of 44/47Sc

2.9. In Vitro Studies

2.9.1. Cell Binding of 44Sc Labeled Bioconjugates

2.9.2. MTT Assay

2.9.3. MTS Assay

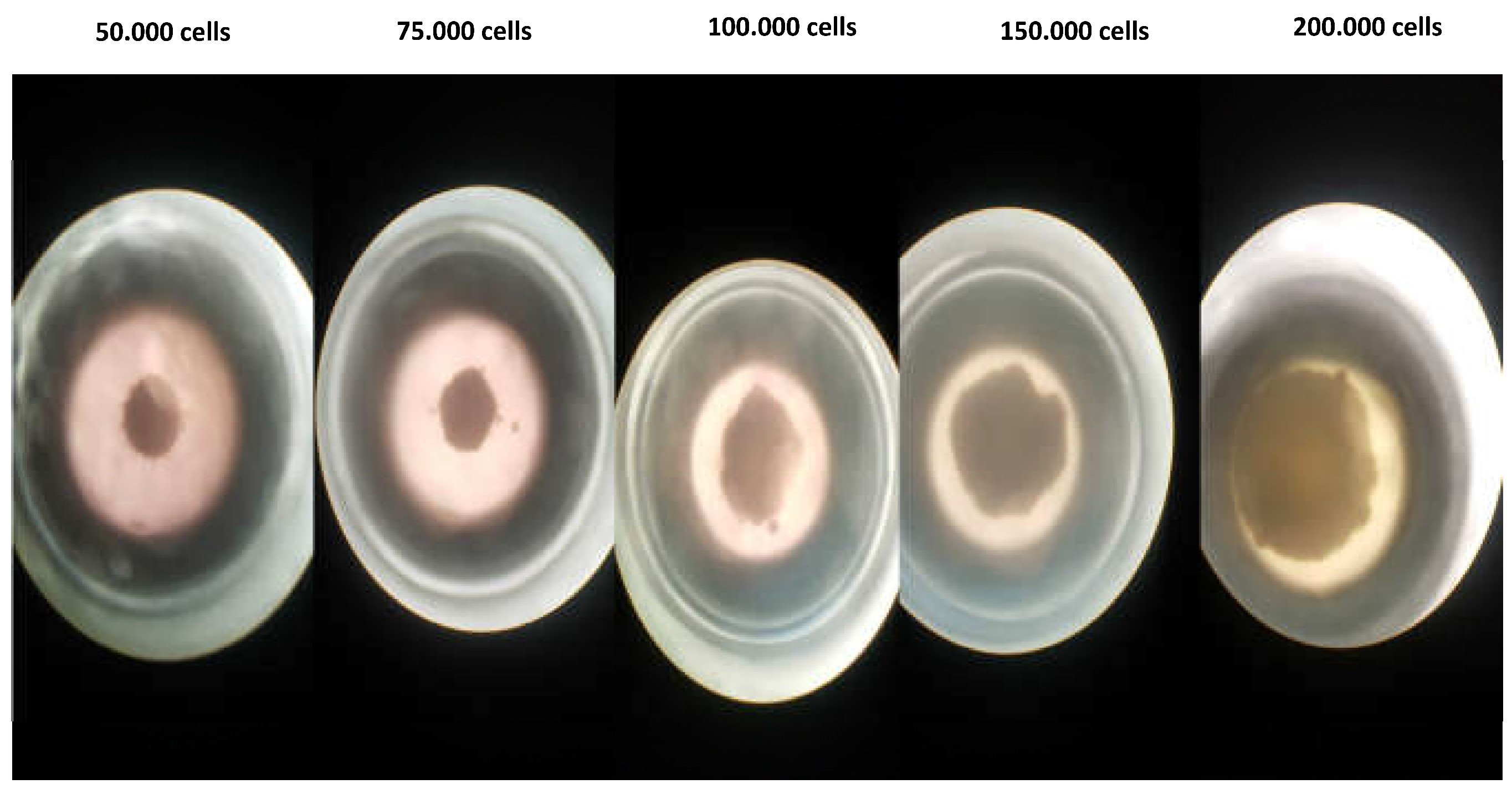

2.9.4. 3D Cell Culture Studies

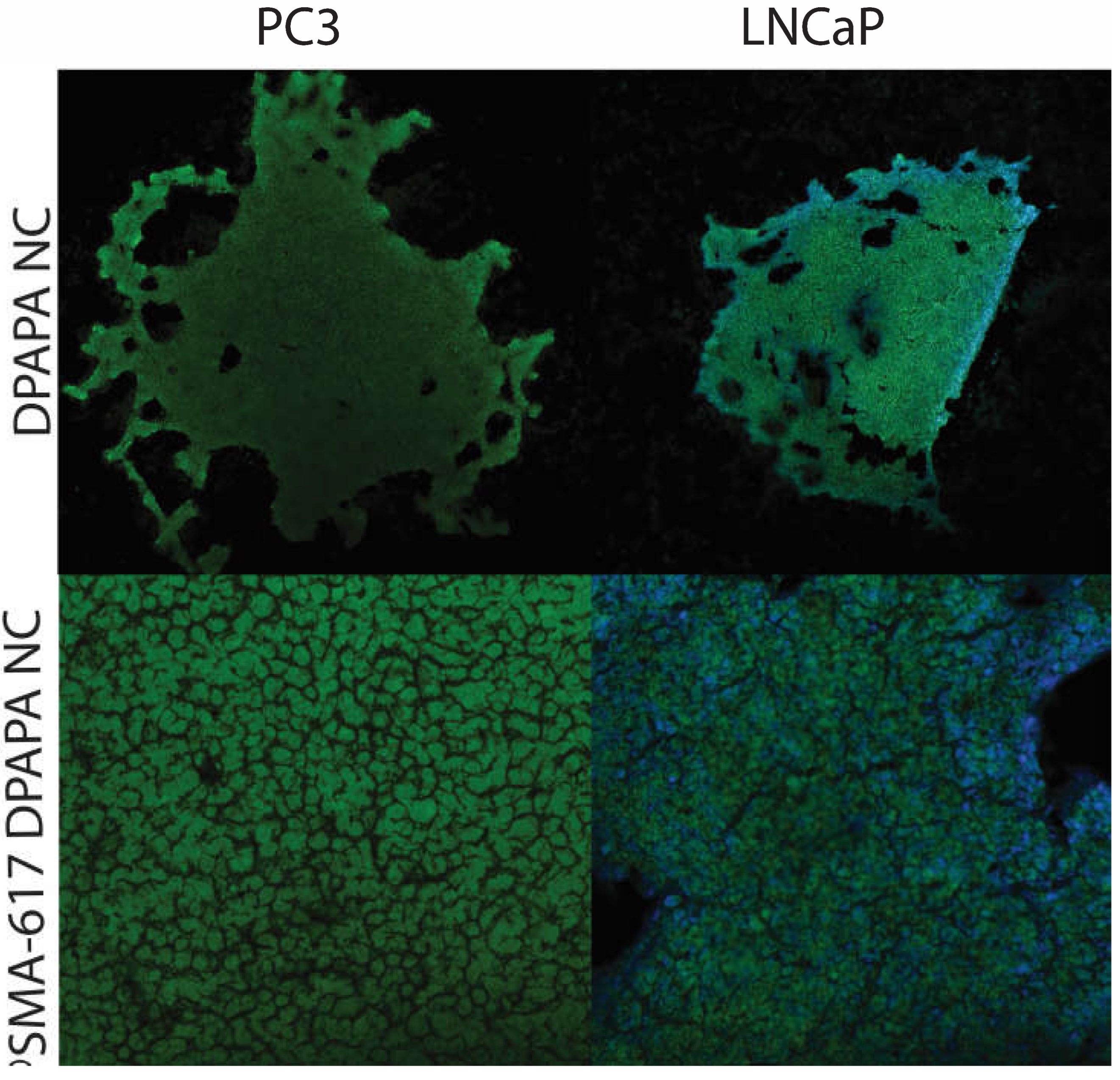

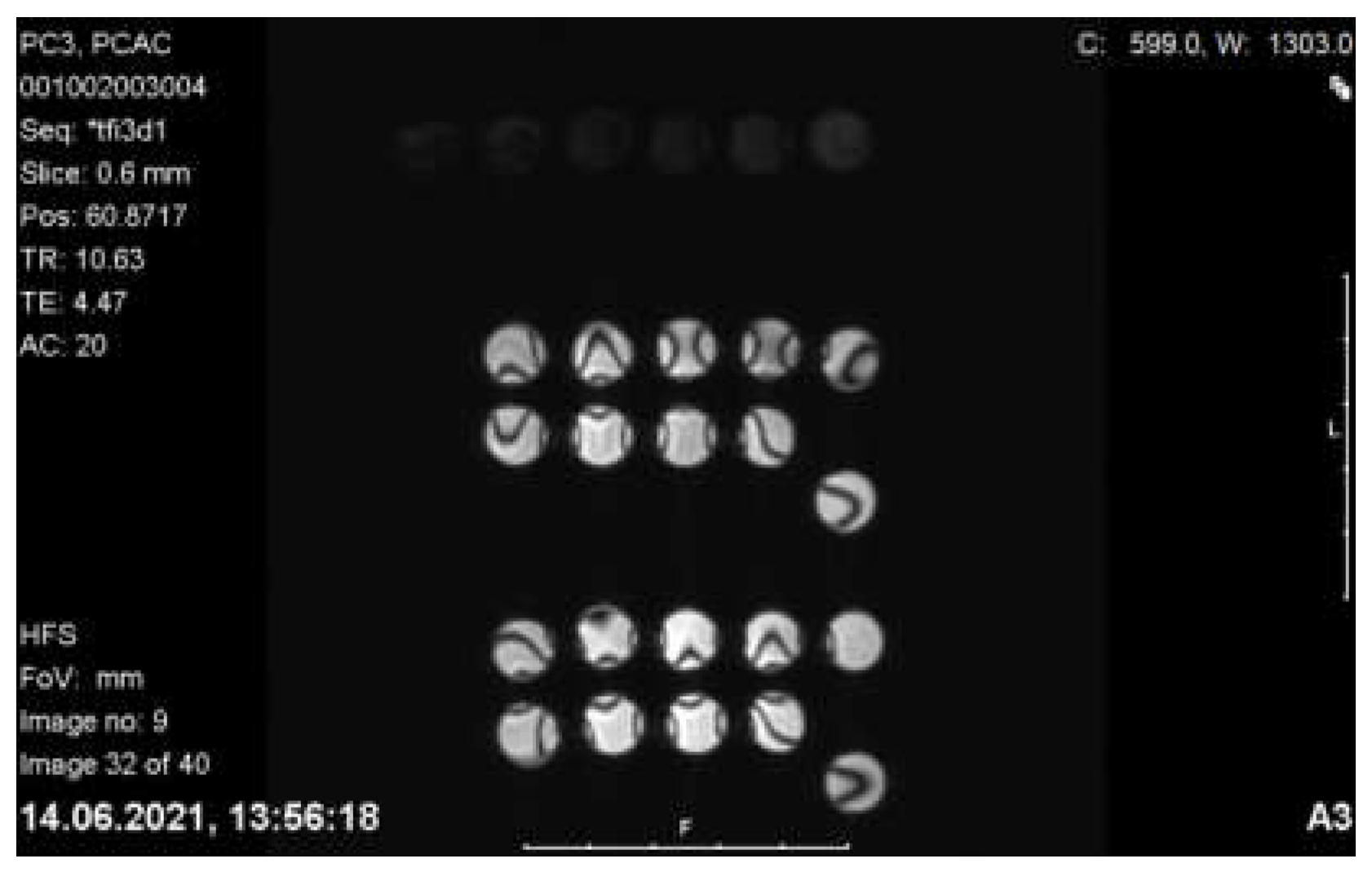

2.9.5. MRI Imaging of PC-3 and LNCaP Cells with Nanoconjugates

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

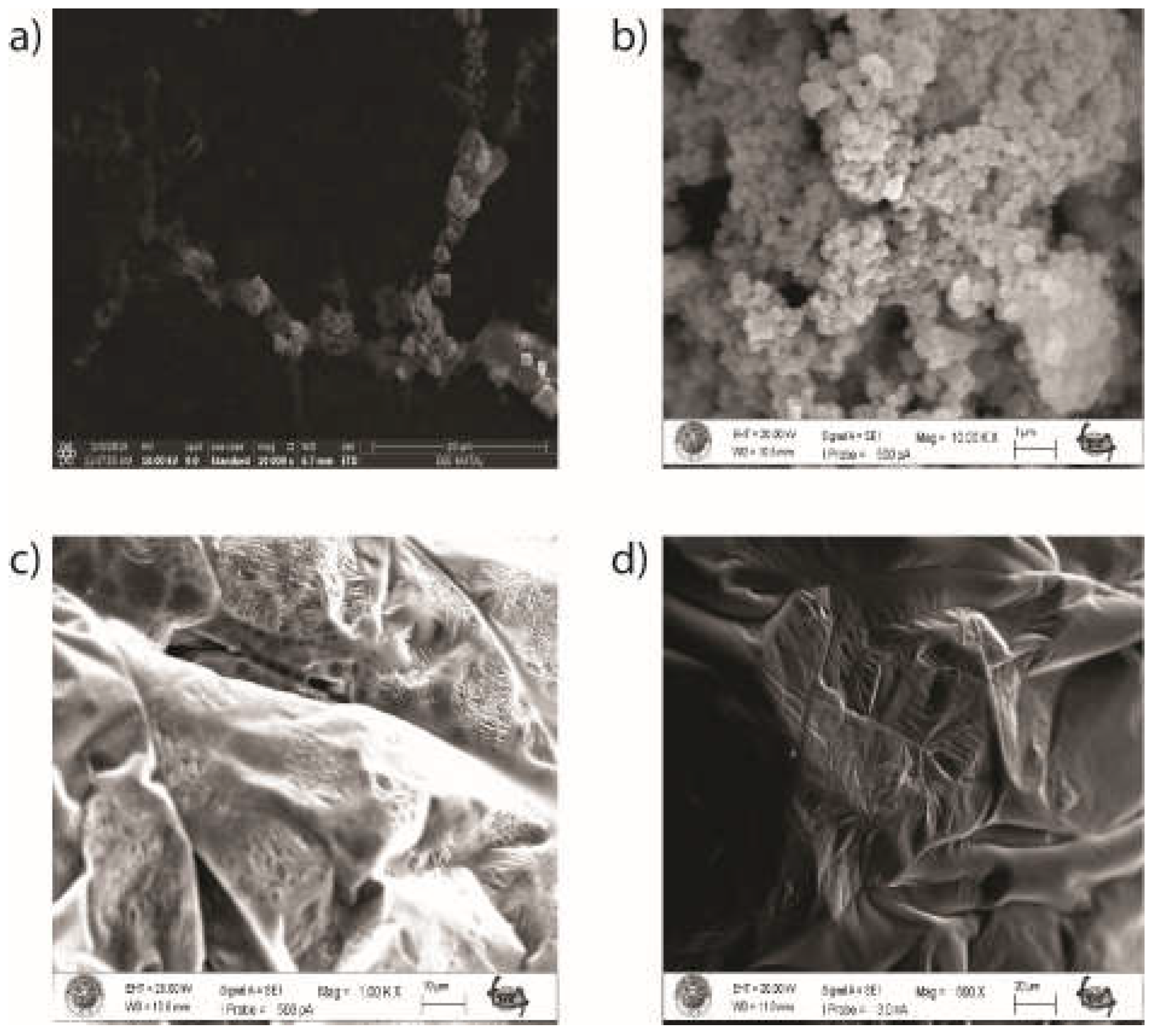

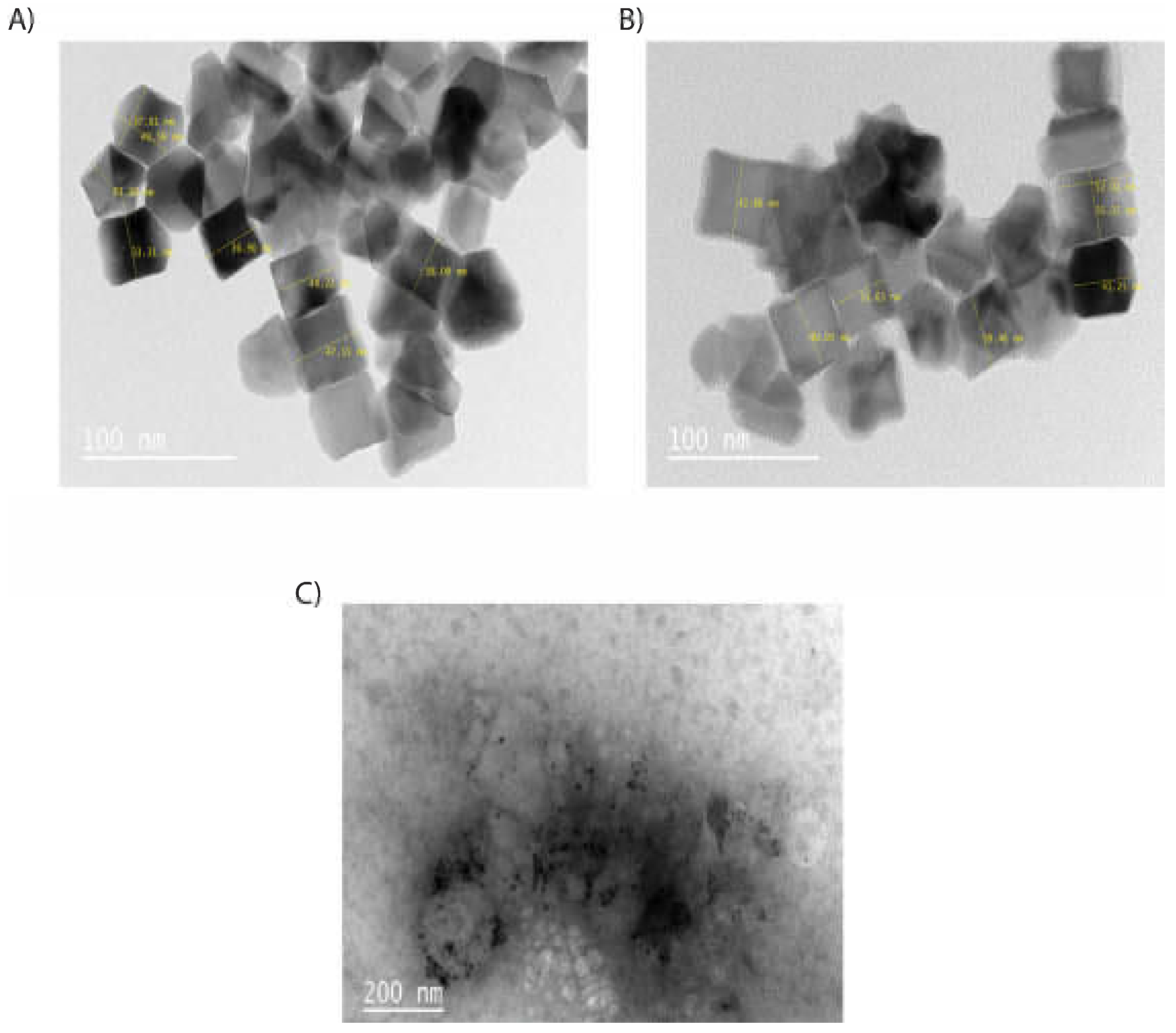

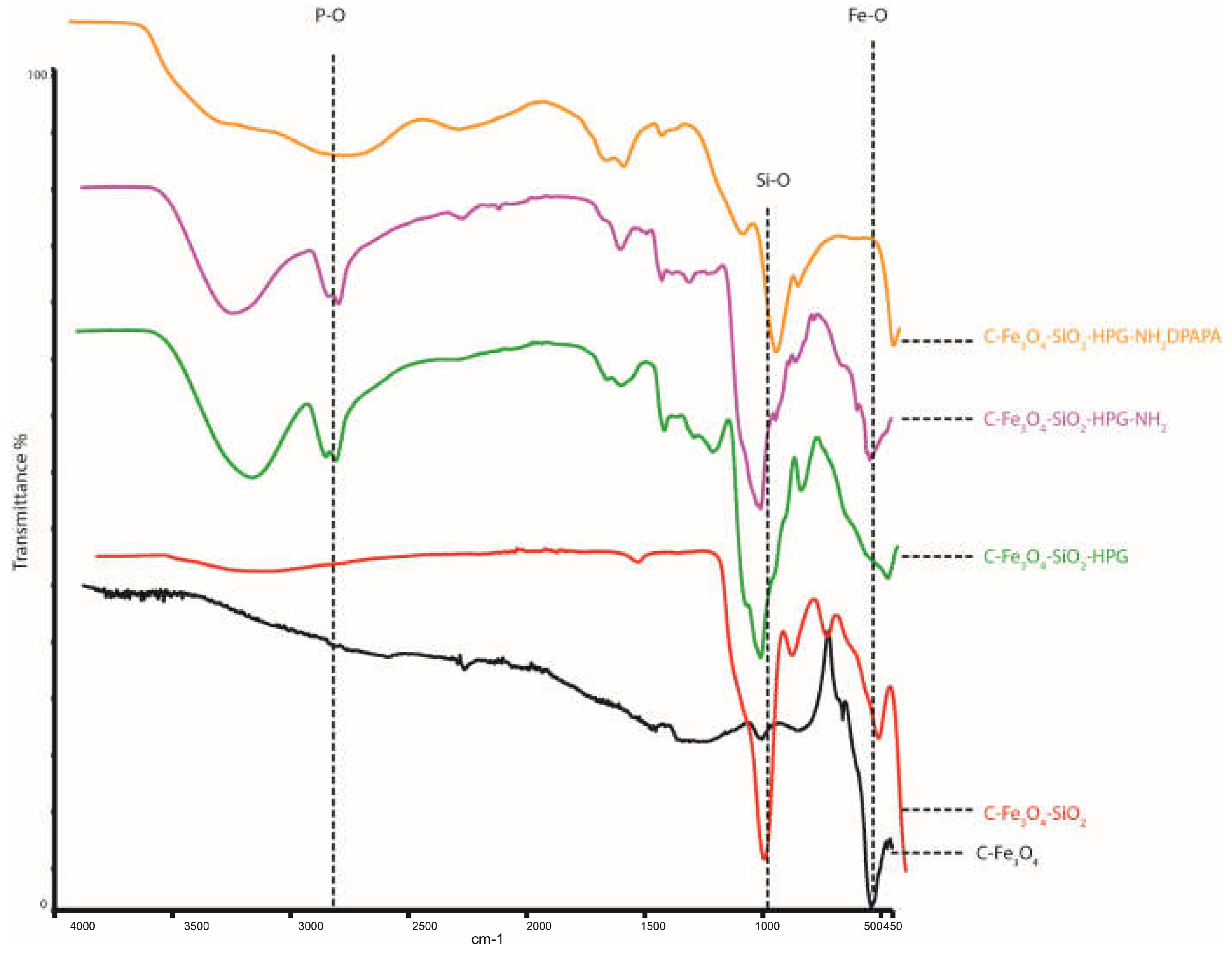

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Nanoparticles and Nanoconjugates

3.2. 44Sc Radiolabeling of Nanoconjugates

3.3. Stability of the obtained radiobioconjugates

3.4. Cell Studies

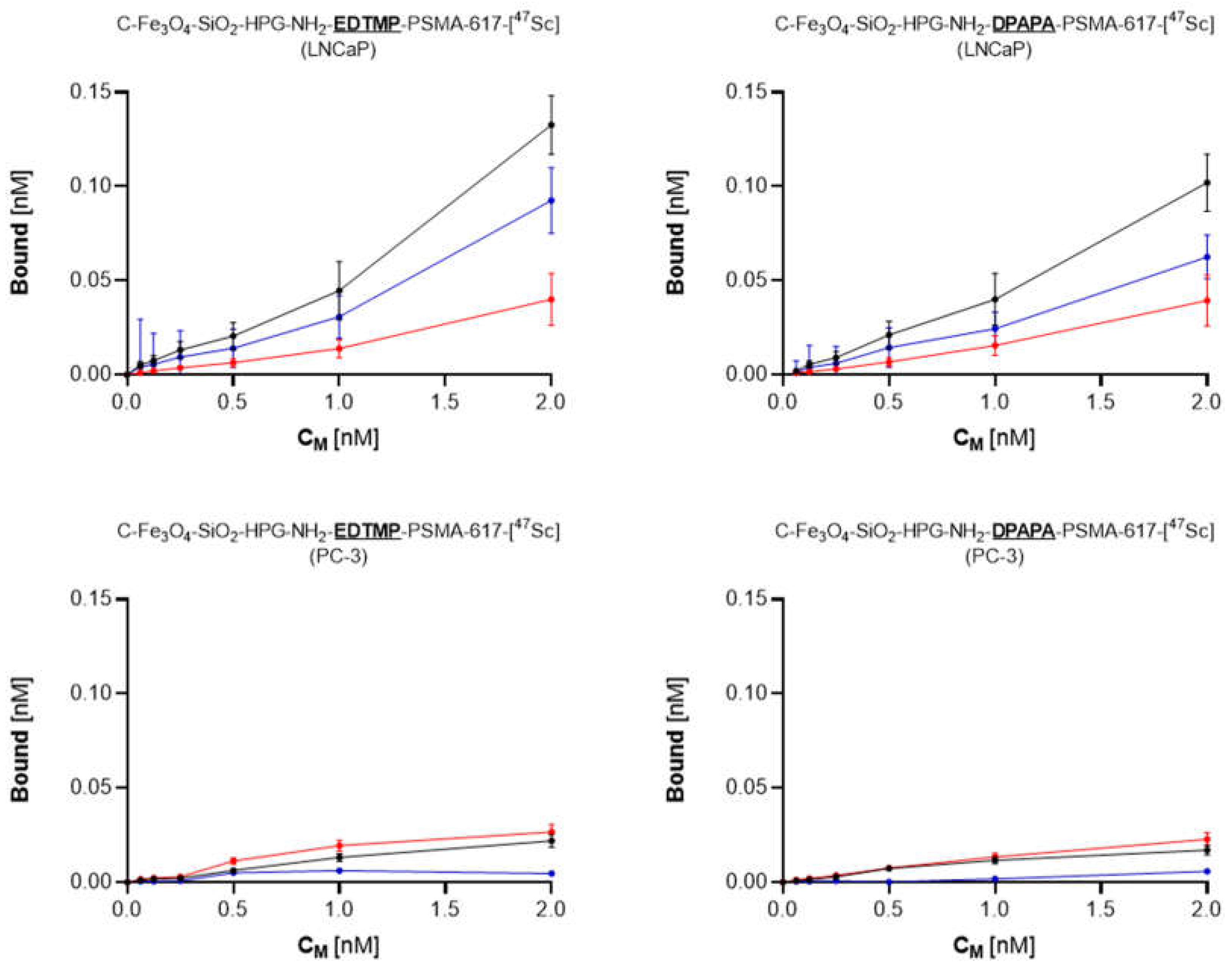

3.4.1. Cell Binding of 44Sc Labeled Bioconjugates

3.4.2. MTT Assay

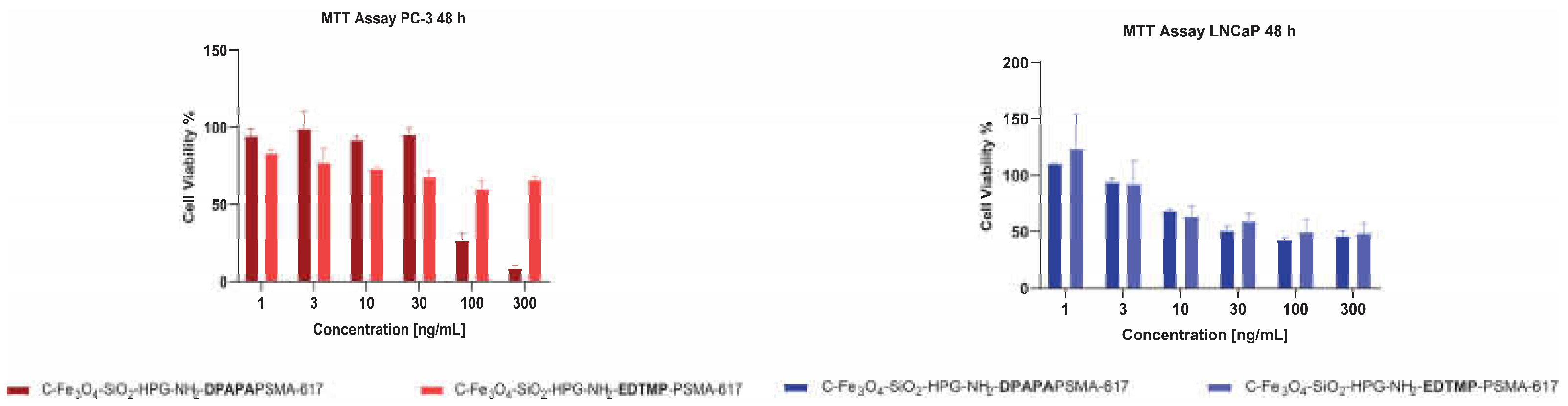

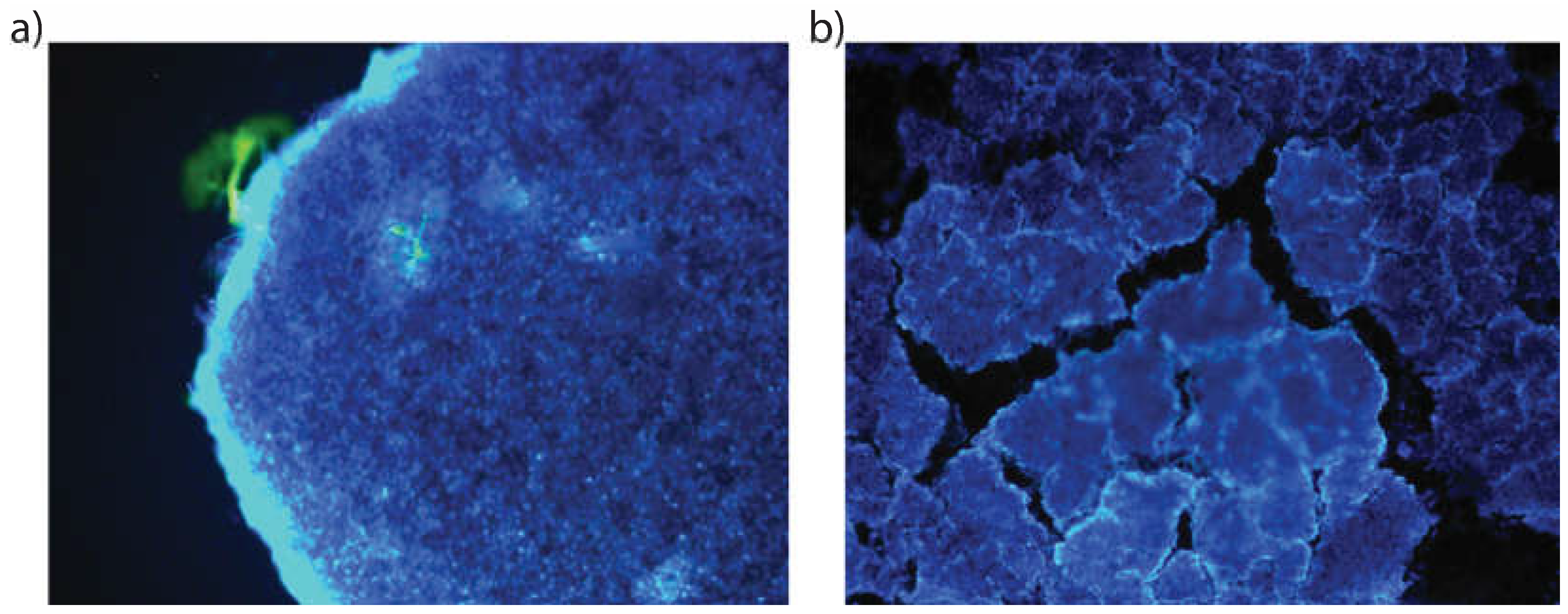

3.4.3. MTS Assay

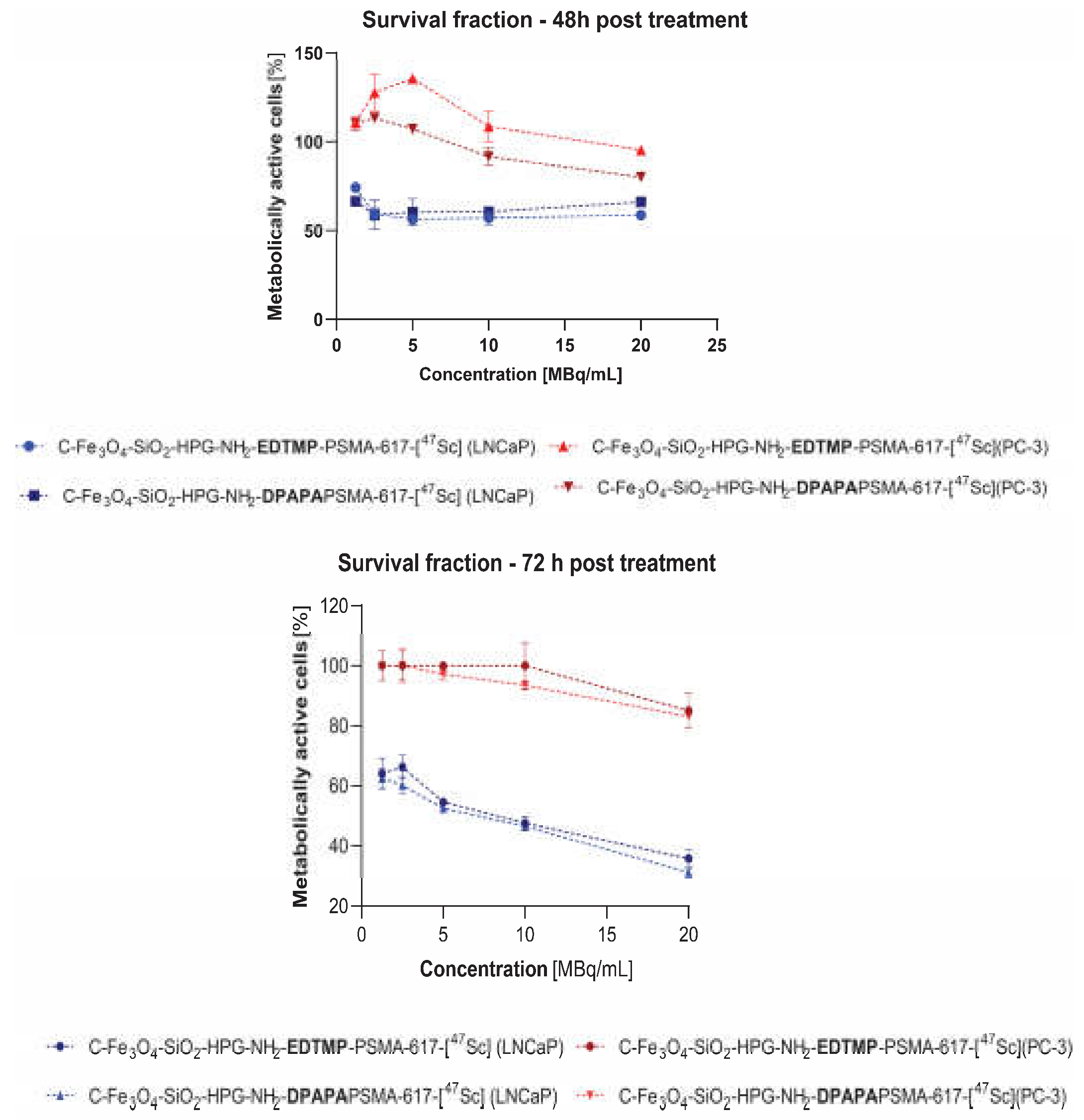

3.4.4. Three-dimensional (3D) Cell Culture Studies

3.4.5. MRI Imaging

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahandar, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Mousavi, H. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Polyglycerol Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles as a Nano-Theranostics Agent. Mater Res Express 2015, 2, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübbe, A.S.; Alexiou, C.; Bergemann, C. Clinical Applications of Magnetic Drug Targeting. J Surg Res 2001, 95, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cędrowska, E.; Pruszyński, M.; Gawęda, W.; Żuk, M.; Krysiński, P.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Karageorgou, M.-A.; Bouziotis, P.; Bilewicz, A. Trastuzumab Conjugated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Labeled with 225Ac as a Perspective Tool for Combined α-Radioimmunotherapy and Magnetic Hyperthermia of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Molecules 2020, 25, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, W.; Pruszyński, M.; Cędrowska, E.; Rodak, M.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Gaweł, D.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Bilewicz, A. Trastuzumab Modified Barium Ferrite Magnetic Nanoparticles Labeled with Radium-223: A New Potential Radiobioconjugate for Alpha Radioimmunotherapy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żuk, M.; Podgórski, R.; Ruszczyńska, A.; Ciach, T.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Bilewicz, A.; Krysiński, P. Multifunctional Nanoparticles Based on Iron Oxide and Gold-198 Designed for Magnetic Hyperthermia and Radionuclide Therapy as a Potential Tool for Combined HER2-Positive Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, S.; Tong, L.; Li, J.; Chen, F.; Han, Y.; Zhao, M.; Xiong, W. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Mediated 131I-HVEGF SiRNA Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Growth in Nude Mice. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Duffy, B.A.; Badar, A.; Lythgoe, M.F.; Årstad, E. Bimodal Imaging of Inflammation with SPECT/CT and MRI Using Iodine-125 Labeled VCAM-1 Targeting Microparticle Conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2015, 26, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kumar, R.; Nagesha, D.; Duclos, R.I.; Sridhar, S.; Gatley, S.J. Integrity of 111In-Radiolabeled Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in the Mouse. Nucl Med Biol 2015, 42, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, B.; Afarideh, H.; Ghannadi-Maragheh, M.; Bahrami-Samani, A.; Yousefnia, H. Absorbed Doses in Humans from 188 Re-Rituximab in the Free Form and Bound to Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Biodistribution Study in Mice. Appl Radiat Isot 2018, 131, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrina, C.; Oppelt, A.; Mitzkus, M.; Berensmeier, S.; Schwaminger, S.P. Silica-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: New Insights into the Influence of Coating Thickness on the Particle Properties and Lasioglossin Binding. MRS Commun 2022, 12, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Malik, S.; Bilal, M.; Ali, N.; Ni, L.; Gao, X.; Hong, K. Polymer-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles. In Biopolymeric Nanomaterials; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 275–292.

- Chapa Gonzalez, C.; Martínez Pérez, C.A.; Martínez Martínez, A.; Olivas Armendáriz, I.; Zavala Tapia, O.; Martel-Estrada, A.; García-Casillas, P.E. Development of Antibody-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for Biomarker Immobilization. J Nanomater 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Neoh, K.-G.; Wang, R.; Zong, B.-Y.; Tan, J.Y.; Kang, E.-T. Methotrexate-Conjugated and Hyperbranched Polyglycerol-Grafted Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Targeted Anticancer Effects. Eur J Pharm Sci 2013, 48, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, X.; Qian, Y.; Chen, W.; Shen, J. Multifunctional Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: An Advanced Platform for Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6278–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaghasi, E.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A. Folic Acid Armed Fe3O4-HPG Nanoparticles as a Safe Nano Vehicle for Biomedical Theranostics. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2018, 82, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari Sheikh Hossein, H.; Jabbari, I.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Taherian, A.; Makvandi, P. Functionalization of Magnetic Nanoparticles by Folate as Potential MRI Contrast Agent for Breast Cancer Diagnostics. Molecules 2020, 25, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dendy, P.P. Further Studies on the Uptake of Synkavit and a Radioactive Analogue into Tumour Cells in Tissue Culture. Br J Cancer 1970, 24, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorente, J.A.; Morote, J.; Raventos, C.; Encabo, G.; Valenzuela, H. Clinical Efficacy of Bone Alkaline Phosphatase and Prostate Specific Antigen in the Diagnosis of Bone Metastasis in Prostate Cancer. J Urol 1996, 155, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Boubeta, C.; Simeonidis, K.; Makridis, A.; Angelakeris, M.; Iglesias, O.; Guardia, P.; Cabot, A.; Yedra, L.; Estradé, S.; Peiró, F.; et al. Learning from Nature to Improve the Heat Generation of Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heister, E.; Neves, V.; Tîlmaciu, C.; Lipert, K.; Beltrán, V.S.; Coley, H.M.; Silva, S.R.P.; McFadden, J. Triple Functionalisation of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Doxorubicin, a Monoclonal Antibody, and a Fluorescent Marker for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Carbon N Y 2009, 47, 2152–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, N.; Moghadam, M.; Abbasi, A. MoO2(Acac)2@Fe3O4/SiO2/HPG/COSH Nanostructures: Novel Synthesis, Characterization and Catalyst Activity for Oxidation of Olefins and Sulfides. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2018, 29, 11991–12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Sinha, S.; Surolia, A. Sugar−Quantum Dot Conjugates for a Selective and Sensitive Detection of Lectins. Bioconjug Chem 2007, 18, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami Samani, A.; Ghannadi-Maragheh, M.; Jalilian, A.; Meftahi, M.; Shirvani, S.; Moradkhani, S. Production, Quality Control and Biological Evaluation of 153Sm-EDTMP in Wild-Type Rodents. Iran J Nucl Med 2009, 7, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Minegishi, K.; Nagatsu, K.; Fukada, M.; Suzuki, H.; Ohya, T.; Zhang, M.-R. Production of Scandium-43 and -47 from a Powdery Calcium Oxide Target via the Nat/44Ca(α,x)-Channel. Appl Radiat Isot 2016, 116, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruszyński, M.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Loktionova, N.S.; Eppard, E.; Roesch, F. Radiolabeling of DOTATOC with the Long-Lived Positron Emitter 44Sc. Appl Radiat Isot 2012, 70, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, L.D.; Tripp, C.P. Reaction of (3-Aminopropyl)Dimethylethoxysilane with Amine Catalysts on Silica Surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci 2000, 232, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Zhao, J.; Jing, L.; McHugh, K.J. Theranostic Nanoparticles with Disease-Specific Administration Strategies. Nano Today 2022, 42, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmiri, S.; Tzitzios, V.; Hadjipanayis, G.C.; Meneses Brassea, B.P.; El-Gendy, A.A. Magnetic Properties and Hyperthermia Behavior of Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Clusters. AIP Adv 2019, 9, 125033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, K.; Knez, Ž.; Konstantinova, E.A.; Kokorin, A.I.; Gyergyek, S.; Leitgeb, M. Structural and Magnetic Characteristics of Carboxymethyl Dextran Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles: From Characterization to Immobilization Application. React Funct Polym 2020, 148, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuser, P.E.; Bubniak, L. dos S.; Silva, M.C. dos S.; Viegas, A. da C.; Castilho Fernandes, A.; Ricci-Junior, E.; Nele, M.; Tedesco, A.C.; Sayer, C.; de Araújo, P.H.H. Encapsulation of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) by Miniemulsion and Evaluation of Hyperthermia in U87MG Cells. Eur Polym J 2015, 68, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honary, S.; Zahir, F. Effect of Zeta Potential on the Properties of Nano-Drug Delivery Systems - A Review (Part 1). Trop J Pharm Res 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çitoğlu, S.; Coşkun, Ö.D.; Tung, L.D.; Onur, M.A.; Thanh, N.T.K. DMSA-Coated Cubic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Shao, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, D. Amino-Functionalized Fe3O4@SiO2 Core–Shell Magnetic Nanomaterial as a Novel Adsorbent for Aqueous Heavy Metals Removal. J Colloid Interface Sci 2010, 349, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E.M.; Skrtic, S.; Koretsky, A.P. Sizing It up: Cellular MRI Using Micron-Sized Iron Oxide Particles. Magn Reson Med 2005, 53, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Li, L.; Chen, D. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Biocompatibility and Drug Delivery. Adv Mat 2012, 24, 1504–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, X.-X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y. Application of Multimodality Imaging Fusion Technology in Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant Tumors under the Precision Medicine Plan. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016, 129, 2991–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasakci, V.; Tekin, V.; Guldu, O.K.; Evren, V.; Unak, P. Hyaluronic Acid-Modified [19F]FDG-Conjugated Magnetite Nanoparticles: In Vitro Bioaffinities and HPLC Analyses in Organs. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2018, 318, 1973–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich IR Spectrum Table & Chart. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/technical-documents/technical-article/analytical-chemistry/photometry-and-reflectometry/ir-spectrum-table (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Hampton, C.; Demoin, D. Vibrational Spectroscopy Tutorial: Sulfur and Phosphorus; Fall 2010 Organic Spectroscopy Dr. Rainer E. Glaser.

- Bekiş, R.; Medine, İ.; Dağdeviren, K.; Ertay, T.; Ünak, P. A New Agent for Sentinel Lymph Node Detection: Preliminary Results. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2011, 290, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medine, E.I.; Ünak, P.; Sakarya, S.; Özkaya, F. Investigation of in Vitro Efficiency of Magnetic Nanoparticle-Conjugated 125I-Uracil Glucuronides in Adenocarcinoma Cells. J Nanopart Res 2011, 13, 4703–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.H.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.-P. High-Magnetic-Moment Multifunctional Nanoparticles for Nanomedicine Applications. J Magn Magn Mater 2007, 311, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveless, C.S.; Blanco, J.R.; Diehl, G.L.; Elbahrawi, R.T.; Carzaniga, T.S.; Braccini, S.; Lapi, S.E. Cyclotron Production and Separation of Scandium Radionuclides from Natural Titanium Metal and Titanium Dioxide Targets. J Nucl Med 2021, 62, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, S.; Cao, L.; Nan, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Hong, Z. A Single-Domain Antibody-Based Anti-PSMA Recombinant Immunotoxin Exhibits Specificity and Efficacy for Prostate Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Ji, Z.; Dong, J.; Chang, C.H.; Wang, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.-P.; Zink, J.I.; Nel, A.E.; et al. Enhancing the Imaging and Biosafety of Upconversion Nanoparticles through Phosphonate Coating. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 3293–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M.M.; Glover, D.K.; Lanza, G.M.; Fayad, Z.A.; Johnson, L.L. Imaging Atherosclerosis and Vulnerable Plaque. J Nucl Med 2010, 51, 51S–65S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aras, O.; Pearce, G.; Watkins, A.J.; Nurili, F.; Medine, E.I.; Guldu, O.K.; Tekin, V.; Wong, J.; Ma, X.; Ting, R.; et al. An In-Vivo Pilot Study into the Effects of FDG-MNP in Cancer in Mice. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0202482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.M.; Lee, D.R.; Park, J.S.; Bae, I.; Lee, Y. Liquid Crystal Nanoparticle Formulation as an Oral Drug Delivery System for Liver-Specific Distribution. Int J Nanomedicine 2016, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ramos, N.; Ibarra, L.E.; Serrano-Torres, M.; Yagüe, B.; Caverzán, M.D.; Chesta, C.A.; Palacios, R.E.; López-Larrubia, P. Iron Oxide Incorporated Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles for Simultaneous Use in Magnetic Resonance and Fluorescent Imaging of Brain Tumors. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanoconjugate | Hydrodynamic size (d.nm) (n=3) | Zeta Potential (mV) (n=3) (pH=7) |

PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Fe3O4 | 116 ± 7.90 | -18.6 ±0.60 | 0.13 |

| C-Fe3O4-SiO2 | 122 ± 0.20 | -21.5 ±0.01 | 0.22 |

| C-Fe3O4-SiO2-HPG | 145.8 ± 3.50 | -18.5 ±0.20 | 0.15 |

| DPAPA NC | 221.9 ± 16.00 | -24.2 ±0.30 | 0.06 |

| 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 24 h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDTMP (HS) | 93.0 | 89.7 | 89.6 | 90.0 | 91.7 |

| EDTMP (PBS) | 98.9 | 97.4 | 97.3 | 98.3 | 96.0 |

| DPAPA (HS) | 95.3 | 94.3 | 92.1 | 92.2 | 84.0 |

| DPAPA (PBS) | 98.4 | 96.8 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 92.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).