Introduction

For decades, the HIV epidemic remains a significant global health challenge, with an estimated 38 million individuals infected globally1. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounts for 71% of the global population of people living with HIV (PLWH)2, with a prevalence rate of 1.4% in Nigeria making it the third most HIV-burdened country2. The burden of HIV in Nigeria is the highest among the female adult population and a known predisposition of maternal mortality with an estimated prevalence of 26.4% among pregnant cohorts 3, 4.

More women have been reported to have symptoms of depression in comparison to men and this gendered pattern has also been found to exist among PLWH5-7. WLWH especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), experience significant psychological challenges, such as depression, stress, and anxiety, as a result of their HIV diagnosis8, 9. Studies have also shown that WLWH is susceptible to suffering from more severe symptoms of mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder7, 10.

Pregnancy and postpartum periods are some of the most vulnerable periods that may contribute to symptoms of depression in women11. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among pregnant women ranges from 11.4% to 40.0%, which is higher than that of women generally12, 13. In a study conducted in Nigeria, the prevalence of postpartum depression was found to be 35.6%14. Pregnant women frequently experience stress as well. Women's brains change structurally, psychologically, and behaviourally throughout pregnancy as they prepare for their new role as mothers15. These changes, however, make pregnant women more prone to stress16, which increases the likelihood of developing prenatal depression symptoms17.

Pregnancy can be a period of increased psychological susceptibility for WLWH due to a variety of environmental factors, disclosure concerns, and HIV-related stigma18. Studies conducted in LMICs, have found that pregnant and postpartum WLWH suffer from a high prevalence of depression19-21. Similarly, a systematic review was conducted in Africa which examined the prevalence of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. The weighted mean prevalence of antenatal and postnatal depression was 23.4% and 22.5%, respectively22. Depression has also been found to be associated with adherence to care and therapy among pregnant WLWH21 which may result in treatment failure and increased vertical HIV transmission8. Additionally, psychological issues such as depression and stress may also have adverse effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT)23.

Women, particularly in developing countries, are more likely to be exposed to risk factors such as poor socioeconomic status which make them more susceptible to the development of perinatal depression24. Depression and psychological stress may act as critical barriers to HIV treatment and prevention as the conditions may be linked. Women are often newly diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy and receive a positive HIV diagnosis in an event that can generate worry as well as fear of transmitting the virus to an unborn child25.

Mental health disorders in pregnant WLWH must be understood in the context of women’s life circumstances. Understanding the magnitude of depression and stress, as well as their associated factors, among pregnant WLWH could provide important information that could aid in the mitigation of the poor mental health experienced by this group of women. To our knowledge, this study is among the few studies that have investigated the prevalence of depression and psychological stress among WLWH during pregnancy and the postpartum period in Nigeria. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with depression and psychological stress among WLWH during their perinatal period in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was a facility-based cross-sectional survey conducted in three (3) HIV treatment centers in Ibadan. The centers were; State Hospital, Adeoyo, Ringroad; Adeoyo Maternity Health Centre; and St Annes Anglican Hospital, Molete. A purposive sampling method was adopted in selecting the health facilities because anti-retroviral treatment is not available in all health facilities. Thus, the health institution provides comprehensive HIV services in addition to antenatal, delivery, and postnatal care.

Study Participants

The participants were randomly selected from the three HIV treatment facilities in Ibadan between September and November 2022. The study population consisted of WLWH over the age of 18 who were pregnant or had given birth within the last two years and were attending any of the three selected anti-retroviral treatment clinics in Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria. The exclusion criteria were women who had existing mental illnesses or were unable to provide explicit consent.

Data Collection

All the questionnaires were interviews administered to WLWH receiving treatment at any of the three anti-retroviral treatment clinics during the course of the study. 402 consented WLWH were enrolled in the study. Before administering the questionnaire, participants were provided with information sheets outlining the objective and scope of the study which was duly explained to the participants in English language or the local dialect (Yoruba).

Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire composed in the English language was administered to the participants, and clarification was provided by the investigators when requested. The questionnaire was divided into two sections. Section one obtained information on the participants’ social demographic, relationship, and support-related, behavioral, clinical, and pregnancy-related characteristics. After completing the first section, the participants were counseled to select their desired answers in section two, which assessed depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)26 and perceived stress using the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10)27. The questions were explained verbally in the requisite local language (Yoruba) for those not fluent in English.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was used to assess symptoms of perinatal depression. The scale has 10 items with responses on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absence of depressive moods) to 3 (worst mood). A total score ranging from 0 to 30 is calculated, and a cut-off point of ≥12 indicates an increased likelihood of clinical depression. The scale does not mention the words pregnancy, child, birth, or infant and has also been validated in a non-pregnant population.

Perceived stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 10-item self-report assessment of the stress domains of unpredictability, lack of control, burden overload, and stressful life circumstances. Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The PSS score is the sum of all responses with higher scores indicating more perceived stress and can range from 0 to 40.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from the completed questionnaire and assessment tools were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science version 25. Descriptive statistics of demographic information for each participant were computed. Descriptive statistics were also used to describe the prevalence of depression and perceived stress. Factors associated with depression and perceived stress were evaluated using multivariate logistic regression.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Lead City University Health Research and Ethics Committee (LCU-REC/22/125) as well as from the Oyo State Ministry of Health Research Ethics Committee (AD 13/479/44539).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

A total of 402 participants were eligible in this study and the mean value of their age was 35.8 years (SD = 6.60 years). A total of 225 (56.0%) participants identified as Christians, the majority 92.3% of them were married and 352 (87.6%) participants were from the Yoruba tribe. Concerning their level of education, those who attained a secondary school education were the majority with 173 (43.0%) participants, while 334 (83.1%) participants were employed and 234 (58.2%) of the participants earn an income below 20,000.00 NGN. (See

Table 1)

Depression and Perceived Stress among Pregnant WLHIV

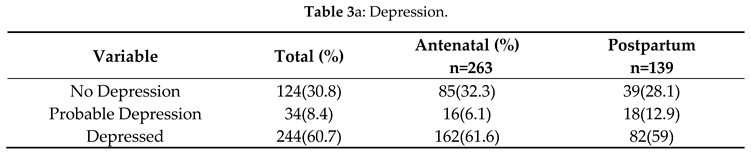

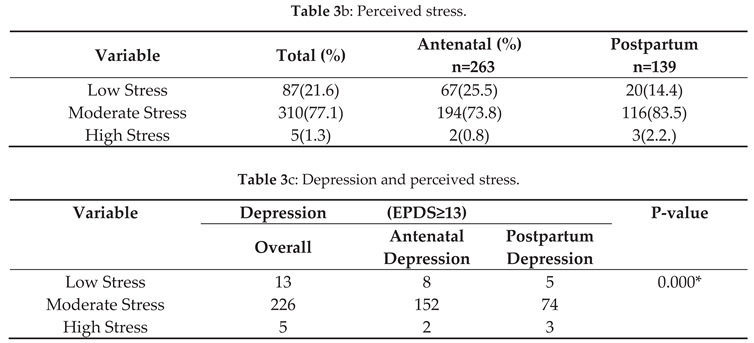

About 69% of the participants were depressed and 78% had perceived stress. According to this study, depression and stress were significantly associated. (See

Table 3)

Table 2.

Relationship and support-related clinical and pregnancy-related characteristics.

Table 2.

Relationship and support-related clinical and pregnancy-related characteristics.

| Characteristics |

Total |

Antenatal (%) |

Postnatal (%) |

| Partners Status(n=402) |

|

|

|

| Positive |

157 |

118(44.9) |

39(28.1) |

| Negative |

178 |

97(36.9) |

81(58.3) |

| Not applicable |

67 |

48(18.2) |

19(13.7) |

| Status Disclosure to partner (n=402) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

246 |

153(58.2) |

93(66.9) |

| No |

148 |

108(41.1) |

40(28.8) |

| Not applicable |

8 |

2(0.8) |

6(4.3) |

| Perceived Social Support |

|

|

|

| Support from partner (n=402) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

318 |

218(82.8) |

100(72) |

| No |

76 |

43(20.9) |

33(23.8) |

| Not applicable |

8 |

2(0.8) |

6(4.3) |

| Support from other family and friends (n=402) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

287 |

56(40.3) |

83(59.7) |

| No |

115 |

59(22.4) |

56(40.3) |

| History of Conflict with Partner |

|

|

|

| Yes |

128 |

80(30.4) |

48(34.5) |

| No |

266 |

181(68.8) |

85(61.2) |

| Not applicable |

8 |

2(0.8) |

6(4.3) |

| Years On ART(n=402) |

|

| ≤ 1 Year |

85 |

50(19) |

35(25.2) |

| ≤ 5 Years |

194 |

136(51.7) |

58(41.7) |

| >5 Years |

77 |

46(17.5) |

15(10.8) |

| > 10 Years |

46 |

31(11.8) |

31(22.3) |

| Viral Load |

|

|

|

| <50 copies/mL |

374 |

243(92.4) |

131(94.2) |

| ≥ 50 copies/mL |

19 |

13(4.9) |

6(4.3) |

| Target Not Detected (TND) |

9 |

7(2.7) |

2(1.4) |

| Problems in Previous Pregnancy (n=402) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

175 |

104(39.5) |

64(46) |

| No |

227 |

159(60.5) |

75(54) |

| Planned Pregnancy (n=263) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

73 |

73(27.8) |

N/A |

| No |

190 |

190(72.2) |

N/A |

| Gestational Age (n=263) |

|

|

|

| 5-13 weeks |

109 |

109(41.4) |

N/A |

| 14-28 weeks |

85 |

85(32.3) |

N/A |

| 29-40 weeks |

69 |

69(26.3) |

N/A |

Table 3.

Prevalence of Depression and Perceived Stress.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Depression and Perceived Stress.

Factors Associated with Perinatal Depression

In the multivariate logistic regression model which examined factors associated with depressive symptoms (see

Table 4), the status of the partner, income level, and gestational age was found to be significantly associated with depression. Women who had positive partners had lower higher odds of depression compared with women who had negative partners (OR=0.6, 95% CI =0.2-1.3). Women who earned an income below 20,000.00 Nigeria naira had 7.0 times higher odds of possible depression compared with women who earned more (OR=7.0, 95% CI= 1.2-40.9). Women who reported having a gestational age above 14 weeks had 5 times higher odds of depression (OR=4.7, 95% Cl=1.7-12.6).

Factors Associated with Perceived Stress

Following a multivariate logistic regression model examining factors associated with perceived stress, gestational age was found to be significantly associated with perceived stress. (See

Table 5)

Factors Associated with the Co-Occurrence of Depression and Perceived Stress

A multivariate logistic regression model was used to examine the factors associated with the co-occurrence of symptoms of depression and perceived stress.

Table 6 showed the status of the partner, income level, support from other family and friends, history of conflict with the partner, whether the pregnancy was planned, gestational age, having problems in a previous pregnancy, and years on ART were significant predictors. Women who earned an income below 20,000.00 NGN had 6 times higher odds of possible depression and perceived stress compared with women who earned more (OR=5.7, 95% CI 1.1-7.8). Women that had planned pregnancies had lower odds of experiencing depression and perceived stress when compared with those that had planned pregnancies (OR=0.3, 95% Cl =0.1-0.8). Also, women who reported experiencing problems in a previous pregnancy were twice as likely to experience a co-occurrence of depression and perceived stress (OR=2.1, 95% Cl =1.6-3.8). Women who reported having a gestational age above 14 weeks had 4.7 times higher odds of depression and perceived (OR=4.7, 95% Cl =4.0-5.5). Women that reported being on ART for 2 to 5 years as of the time of the survey were also found 2.3 times higher odds of experiencing a co-occurrence of depression and perceived stress(OR=2.3, 95% Cl =1.3-4.3).

Discussion

This study determined the prevalence and factors associated with depression and psychological stress among WLWH during their perinatal period in Ibadan, Nigeria. The study results show a high prevalence of perinatal symptoms (60.7%) with antenatal depression and postpartum depression having a prevalence of 61.6% and 58.9% respectively. The prevalence of perinatal depression is higher than 38.4% in a similar study in Ethiopia 21. The prevalence of antenatal depression of 61.6% as measured by the EPDS with a cut-off ≥13 is slightly higher than the prevalence found in a previous study in Ekiti State, Nigeria (49.5%)28, 47.6% in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 21, and 52.5% in India among women on ART 29. The differences in prevalence might be due to differences in sociodemographic characteristics and tools used to assess depression. However, this finding buttresses the need to integrate mental health services into routine HIV care services especially among women to mitigate the adverse associated with maternal and child outcomes.

In the current study, the mean perceived stress was 20.01. This indicates moderate stress among WLHIV during the perinatal period. This finding is consistent with what was reported in another study carried out in Nigeria, in which the mean perceived stress was moderate among the study population30. The level of stress among the participants plausible predisposes to higher risks of mental disorders as it is in the general population and settings with social inequalities 31. Stress is an important risk factor for depressive symptoms 32. Similar to other studies, it was found that women within the study sample that reported depressive symptoms (64.0%) reported significantly higher levels of perceived stress than women without depressive symptoms (28.0%).

This study used multivariate analysis to highlight factors associated with perinatal depression and perceived stress in a sample of WLWH recruited from ART clinics. The study found that the status of the partner of participants was significantly associated with depression and perceived stress. With an odds ratio of 0.389, participants with a positive partner were less likely to report symptoms of depression and perceived stress as compared to women with negative partners. This may be due to the social support provided by a positive partner as opposed to a negative partner. Studies also corroborate that having a positive partner increases the likelihood of having access to help when sick, general support in form of finances as well as HIV-specific support 33. According to the study, participants who earned below 20,000 were 5.6 times more likely to report symptoms of depression and perceived stress. The results are consistent with those reported in studies in Ethiopia and South Africa, which presented that low income and unemployment were related to depression among HIV-positive women 24, 34. The reason could be that in low-income countries, women are pressured to default academics for poverty-related factors, which later result in their more prominent engagement in domestic work, as well as the lack of access to health education and awareness. This is ascribed to the possible negative interaction between mental disorders (e.g., depression) and poverty, primarily because, in principle, people with depression commonly perform poorly in their daily tasks 35. In addition, pregnancy may decrease their employability and even their potential to work because of the type of labor impoverished women may need to undertake 36.

The results from this study also revealed that having a planned pregnancy (OR=0.348, 95% Cl 0.149-0.819), is indicative of a lower likelihood of reporting symptoms of depression and perceived stress during the perinatal period. According to the study, pregnant women within their second (14-28 weeks) and third (29-40 weeks) trimesters were more likely to report symptoms of depression and perceived stress with odds of 4.7 and 3.7 respectively. This is in contrast with other studies which have reported no association between gestational age and depression among women living with HIV. This could be due to physiological changes which take place during this period which may be inclinatory to the development of depression. It could also be due to heightened anxiety during the third trimester 37, 38. This study indicates having problems in a previous pregnancy (OR = 2.10) was significantly associated with the co-occurrence of depression and perceived stress. This indicates that women living with HIV that had complications in their previous pregnancy were twice as likely to report symptoms of depression and perceived stress as compared to those that did not. This could be a result of the complications being events that were highly severe and stressful to them. This finding is in line with previous studies which reported that having previous complications in pregnancy is a significant factor in the development of depression 39.

Conclusion

This study reveals a substantial prevalence of depression, perceived stress, and the co-occurrence of depression and perceived stress in the population of WLHIV. The study recommends that screening for prenatal and postpartum depression and access to mental health interventions should be part of routine maternal healthcare for all women, especially those living with HIV.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, O.C. and F.T.; methodology, A.L., S.B., and F.T.; software, S.B., and H.O..; validation, F.T.., A.L., and Z.A.; formal analysis, S.B.; investigation, Z.A., I.A., and D.R.; resources, F.T.; data curation, S.B., F.T., and H.O.; writing—original draft preparation, F.T., and A.L.; writing—review and editing, A.L., O.A., D.R., H.O., D.N., and A.S.; supervision, F.T., and O.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lead City University, Ibadan (Protocol code: LCU-REC/22/125 and date of approval: September 05, 2022) as well as from the Oyo State Ministry of Health Research Ethics Committee (Protocol code: AD 13/479/44539 and date of approval: August 15, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Fogarty International Center (FIC) and the National Institute of Health (Funding provided by Fogarty Training Grant: D43TW010934-03). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

References

- Global, H. AIDS statistics—2019 fact sheet [https://www. unaids. org/en/resources/fact-sheet]. Accessed, 2021.

- James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegbom, A.I.; Edet, C.K.; Ogba, A.A.; et al. Determinants of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Pregnant Women Attending Tertiary Hospitals in Urban Centers, Nigeria. Women 2023, 3, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonko, I.O.; Osadebe, A.U.; Onianwa, O.; et al. Prevalence of HIV in a cohort of pregnant women attending a tertiary hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. Immunology and Infectious Diseases 2019, 7, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Journal of psychiatric research 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, C.; Dabis, F.; de Rekeneire, N. Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 2017, 12, e0181960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, E.M.; Burnett-Zeigler, I.; Wee, V.; et al. Mental health in women living with HIV: the unique and unmet needs. J Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care 2021, 20, 2325958220985665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Tan, Y.; Lu, B.; et al. Survey and analysis for impact factors of psychological distress in HIV-infected pregnant women who continue pregnancy. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2019, 32, 3160–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffell, S. Stigma kills! The psychological effects of emotional abuse and discrimination towards a patient with HIV in Uganda. J Case Reports 2017, 2017, bcr-2016-218024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.K.; Melo, E.S.; de Castro Castrighini, C.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptoms in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Salud mental 2017, 40, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Mello, M.C.D.; Patel, V.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2012, 90, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellmeth, G.; Fazel, M.; Plugge, E.; et al. Migration and perinatal mental health in women from low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 124, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, A.; Yin, J.; Waqas, A.; et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 277, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, E.; Oluwole, E.; Kanma-Okafor, O.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among postnatal women in Lagos, Nigeria. J African health sciences 2020, 20, 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekzema, E.; Barba-Müller, E.; Pozzobon, C.; et al. Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. J Nature neuroscience 2017, 20, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P. How stress can influence brain adaptations to motherhood. J Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 2021, 60, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, N.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Sletner, L.; et al. A prospective cohort study of depression in pregnancy, prevalence and risk factors in a multi-ethnic population. J BMC pregnancy childbirth 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Dass-Brailsford, P.; Nora, D.; et al. Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: a comprehensive literature review. J AIDS Behavior 2014, 18, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, H.K.; Mekonnen, C.K.; Ferede, Y.M. Depression Among HIV-Positive Pregnant Women at Northwest Amhara Referral Hospitals During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Risk Management Healthcare Policy 2021, 14, 4897–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngocho, J.S.; Watt, M.H.; Minja, L.; et al. Depression and anxiety among pregnant women living with HIV in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. J PLoS One 2019, 14, e0224515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, W.; Gebremariam, M.; Molla, M.; et al. Prevalence of depression among HIV-positive pregnant women and its association with adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, N.A.; Cholera, R.; Pence, B.W.; et al. Perinatal depression in HIV-infected African women: a systematic review. J The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2015, 76, 14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarde, A.; Morais, M.; Kingston, D.; et al. Neonatal outcomes in women with untreated antenatal depression compared with women without depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J JAMA psychiatry 2016, 73, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, A.; Musa, R.; Isa, M.L.M.; et al. Anxiety and depression among women living with HIV: prevalence and correlations. J Clinical practice epidemiology in mental health: CP EMH 2020, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiba, S. When pregnancy coincides with positive diagnosis of hiv: Accounts of the process of acceptance of self and motherhood among women in South Africa. J International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 2021, 18, 13006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; McKenzie-McHarg, K.; Shakespeare, J.; et al. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. J Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2009, 119, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, J.W.; Harrington, L.N.; Storch, E.A. Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. J Journal of College Counseling 2006, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade-Ojo, I.P.; Dada, M.U.; Adeyanju, T.B. Comparison of Anxiety and Depression Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Pregnant Women During COVID-19 Pandemic in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. J International Journal of General Medicine 2022, 15, 4123–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, A.; Singh, R.J.; Duggal, M.; et al. The prevalence and determinants of depression among HIV-positive perinatal women receiving antiretroviral therapy in India. J Archives of women's mental health 2019, 22, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamu, A.; Mchunu, G.; Naidoo, J.R. Stress and resilience among women living with HIV in Nigeria. J African Journal of Primary Health Care Family Medicine 2019, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Balfour, R.; Bell, R.; et al. Social determinants of mental health. J International review of psychiatry 2014, 26, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.S.N.H.; Laving, A.; Okech-Helu, V.; et al. Depression, perceived stress, social support, substance use and related sociodemographic risk factors in medical school residents in Nairobi, Kenya. J BJPsych Open 2021, 7, S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveniuk, J.; Calzavara, L.; Bullock, S.; et al. Social capital and HIV-serodiscordance: Disparities in access to personal and professional resources for HIV-positive and HIV-negative partners. J SSM-population health 2022, 17, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Rodriguez, V.J.; Jones, D. Prevalence of prenatal depression and associated factors among HIV-positive women in primary care in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. J SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS 2016, 13, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jarad, A.; Al Hadi, A.; Al Garatli, A.; et al. Impact of cognitive dysfunction in the middle east depressed patients: the ICMED study. J Clinical Practice Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP EMH 2018, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeneabat, T.; Bedaso, A.; Amare, T. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in people living with HIV attending antiretroviral clinic at Fitche Zonal Hospital, Central Ethiopia: cross-sectional study conducted in 2012. J Neuropsychiatric disease treatment 2017, 13, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshoeshoe, M.; Madiba, S. Parenting the child with HIV in limited resource communities in South Africa: Mothers with HIV’s emotional vulnerability and hope for the future. J Women's Health 2021, 17, 17455065211058565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, Z.; Pourasghar, M.; Khalilian, A.; et al. A review of the effects of anxiety during pregnancy on children’s health. J Materia socio-medica 2015, 27, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, O.; Onyenyirionwu UJJoWH and Development. Psycho-social predictors of peripartum depression among Nigerian women. Journal of Women’s Health and Development 2019, 2, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n =402).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n =402).

| Characteristics |

Total n=402 |

Antenatal (n=263) |

Postnatal (n=139) |

| Age (n=402) |

|

|

|

| Mean (S.D) |

35.8(6.6) |

|

|

| Religion |

|

|

|

| Christianity |

225 |

150(57%) |

75(54%) |

| Islam |

176 |

113(43%) |

64(46%) |

| Tribe |

|

|

|

| Yoruba |

352 |

225(85.6) |

127(91.4) |

| Igbo |

29 |

21(8) |

8(5.8) |

| Hausa |

20 |

16(6) |

4(2.9) |

| Others |

1 |

1(0.4) |

0 |

| Level of Education |

|

|

|

| Primary Level |

94 |

53(20.2) |

41(29.5) |

| Secondary Level |

173 |

107(40.7) |

66(47.5) |

| Tertiary Level |

90 |

68(25.9) |

22(15.8) |

| None |

45 |

35(13.3) |

10(7.2) |

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

| Married |

371 |

246(93.5) |

125(89.9) |

| Divorced |

9 |

6(2.3) |

3(2.2) |

| Widowed |

8 |

7(2.7) |

1(0.7) |

| Separated |

8 |

4(1.5) |

4(2.9) |

| Single |

6 |

0 |

6(4.3) |

| Type of Partner |

|

|

|

| Spouse |

373 |

247(93.9) |

126(90.6) |

| Steady |

11 |

7(2.7) |

4(2.9) |

| Casual |

10 |

7(2.7) |

3(2.2) |

| None |

8 |

2(0.8) |

6(4.3) |

| Employment Status |

|

|

|

| Employed |

334 |

225(85.6) |

109(78.4) |

| Unemployed |

68 |

38(14.4) |

30(21.6) |

| Income Level |

|

|

|

| <20,000 |

234 |

157(59.7) |

77(55.4) |

| 20,000-30,000 |

48 |

19(7.2) |

29(20.9) |

| 31,000-40,000 |

77 |

60(22.8) |

17(12.2) |

| 41,000-50,000 |

27 |

13(4.9) |

14(10.1) |

| >51,000 |

16 |

14(5.3) |

2(1.4) |

Table 4.

Factors of perinatal depression.

Table 4.

Factors of perinatal depression.

| Variable |

Depression (EPDS ≥ 13) |

Odd Ratio |

P-value |

| |

Overall |

Antenatal |

Postpartum |

| Status of Partner |

|

|

|

|

|

| Positive |

110 |

82 |

28 |

0.560(0.242, 1.297) |

0.012 |

| Negative |

103 |

60 |

43 |

Ref |

|

| Status Disclosure |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

158 |

109 |

49 |

4.750(0.681,33.131) |

0.092 |

| Yes |

82 |

52 |

30 |

Ref |

|

| Income Level |

|

|

|

|

|

| <20,000 |

121 |

72 |

49 |

6.963(1.184,40.951) |

0.032 |

| 20,000-30,000 |

37 |

19 |

18 |

3.046(0.421,22.041) |

0.270 |

| 31,000-40,000 |

60 |

52 |

8 |

5.481(0.808,37.179) |

0.082 |

| 41,000-50,000 |

16 |

11 |

5 |

4.768(0.552,41.182) |

0.156 |

| >51,000 |

10 |

8 |

2 |

Ref |

|

| Support from Other Family and Friends |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

84 |

49 |

35 |

0.500(0.246,1.015) |

0.050 |

| Yes |

160 |

113 |

47 |

Ref |

|

| History of Conflict with Partner |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

140 |

99 |

41 |

2.462(1.315,4.608) |

0.005 |

| Yes |

100 |

62 |

38 |

Ref |

|

| Gestational Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| 14-28 weeks |

73 |

73 |

N/A |

4.677(1.740,12.574) |

0.002 |

| 29-40 weeks |

54 |

54 |

N/A |

0.219(0.059, 0.817) |

0.024 |

| 5-13 weeks |

35 |

35 |

N/A |

Ref |

|

| Problems in Previous Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

37 |

37 |

N/A |

1.323(0.758,2.309) |

0.325 |

| Yes |

125 |

125 |

N/A |

Ref |

|

| Years on ART |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤ 1 Year |

48 |

28 |

20 |

2.007(0.996,4.044) |

0.051 |

| ≤ 5 Years |

102 |

74 |

28 |

1.869(1.008,3.465) |

0.047 |

| > 5 Years |

56 |

34 |

22 |

Ref |

|

| > 10 Years |

38 |

26 |

12 |

0.623(0.236,1.643) |

0.339 |

Table 5.

Factors associated with perceived stress.

Table 5.

Factors associated with perceived stress.

| Variable |

Stress(PSS-10 ≥ 14) |

Odd Ratio |

P-value |

| Overall |

Antenatal |

Postnatal |

| Status of Partner |

|

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

148 |

113 |

35 |

0.363(0.104,1.266) |

0.112 |

| Positive |

166 |

95 |

71 |

Ref |

|

| Status Disclosure |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

138 |

102 |

36 |

2.026(0.173,23.757) |

0.574 |

| Yes |

228 |

145 |

83 |

Ref |

|

| Income Level |

|

|

|

|

|

| <20,000 |

218 |

147 |

71 |

0.193(0.041,0.915) |

0.038 |

| 20,000-30,000 |

46 |

19 |

27 |

0.078(0.078,0.009) |

0.019 |

| 31,000-40,000 |

72 |

59 |

13 |

0.316(0.052,1.917) |

0.210 |

| 41,000-50,000 |

24 |

12 |

12 |

0.277(0.0.035,2.177) |

0.222 |

| >51,000 |

13 |

11 |

2 |

Ref |

|

| Support from other family and friends |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

107 |

55 |

52 |

0.632(0.240,1.663) |

0.353 |

| Yes |

266 |

193 |

73 |

Ref |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gestational Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| 14-28 weeks |

84 |

84 |

N/A |

0.323(0.083,1.261) |

0.104 |

| 29-40 weeks |

61 |

61 |

N/A |

0.054(0.006, 0.500) |

0.010 |

| 5-13 weeks |

103 |

103 |

N/A |

Ref |

|

| Problems in Previous pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

214 |

150 |

64 |

1.489(0.613,3.620) |

0.379 |

| Yes |

159 |

98 |

61 |

Ref |

|

| Years on ART |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤ 1 Year |

84 |

50 |

34 |

0.214(0.023,1.970) |

0.174 |

| ≤ 5 Years |

175 |

123 |

52 |

1.875(0.611,5.753) |

0.272 |

| > 5 Years |

73 |

46 |

27 |

Ref |

|

| > 10 Years |

41 |

29 |

12 |

2.175(0.552,8.568) |

0.267 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

Factors of depression and perceived stress.

Table 6.

Factors of depression and perceived stress.

| Variable |

Depression and Stress (EPDS ≥ 13, PSS-10 ≥ 14) |

Odd Ratio |

P-value |

| Overall |

Antenatal |

Postpartum |

| Status of Partner |

|

|

|

|

|

| Positive |

108 |

80 |

28 |

0.389(0.165,0.915) |

0.031 |

| Negative |

122 |

70 |

52 |

Ref |

|

| Status Disclosure |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

84 |

53 |

31 |

0.571(0.270,10.735) |

0.571 |

| Yes |

170 |

112 |

58 |

Ref |

|

| Income Level |

|

|

|

|

|

| <20,000 |

124 |

73 |

51 |

5.690(1.050,7.832) |

0.044 |

| 20,000-30,000 |

39 |

19 |

20 |

1.706(0.256,11.363) |

0.581 |

| 31,000-40,000 |

63 |

52 |

11 |

2.973(0.491,17.998) |

0.236 |

| 41,000-50,000 |

21 |

12 |

9 |

2.781(0.353,21.921) |

0.332 |

| >51,000 |

12 |

10 |

2 |

Ref |

|

| Support from other family and friends |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

89 |

117 |

53 |

0.488(0.244,0.976) |

0.042 |

| Yes |

170 |

49 |

40 |

Ref |

|

| History of Conflict with Partner |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

156 |

106 |

50 |

2.462(1.315,4.608) |

0.005 |

| Yes |

98 |

39 |

59 |

Ref |

|

| Planned Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

35 |

35 |

N/A |

0.348(0.149, 0.819) |

0.015 |

| No |

131 |

131 |

N/A |

Ref |

|

| Gestational Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| 29-40 weeks |

52 |

52 |

N/A |

3.673(1.339,10.077) |

0.012 |

| 14-28 weeks |

79 |

79 |

N/A |

4.677(0.042,0.529) |

0.003 |

| 5-13 weeks |

35 |

35 |

N/A |

Ref |

|

| Problems in Previous Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

106 |

52 |

54 |

2.106(1.157,3.833) |

0.015 |

| No |

153 |

114 |

39 |

Ref |

|

| Years on ART |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤ 1 Year |

53 |

31 |

22 |

1.988(0.997,3.963) |

0.051 |

| ≤ 5 Years |

112 |

75 |

37 |

2.343(1.282,4.281) |

0.006 |

| > 5 Years |

59 |

36 |

23 |

1.016(1.061,0.430) |

0.971 |

| > 10 Years |

35 |

24 |

11 |

Ref |

|

| Viral Load |

|

|

|

|

|

| Target not detected (TND) |

7 |

6 |

1 |

0.446(0.046,4.289) |

0.485 |

| <50 copies/mL |

243 |

154 |

89 |

0.901(0.272,2,982) |

0.864 |

| >=50 copies/mL |

9 |

6 |

3 |

Ref |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).