Submitted:

28 February 2023

Posted:

01 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Analysis of gene sequence

Analysis of missense SNPs with amino acid change

3. Results

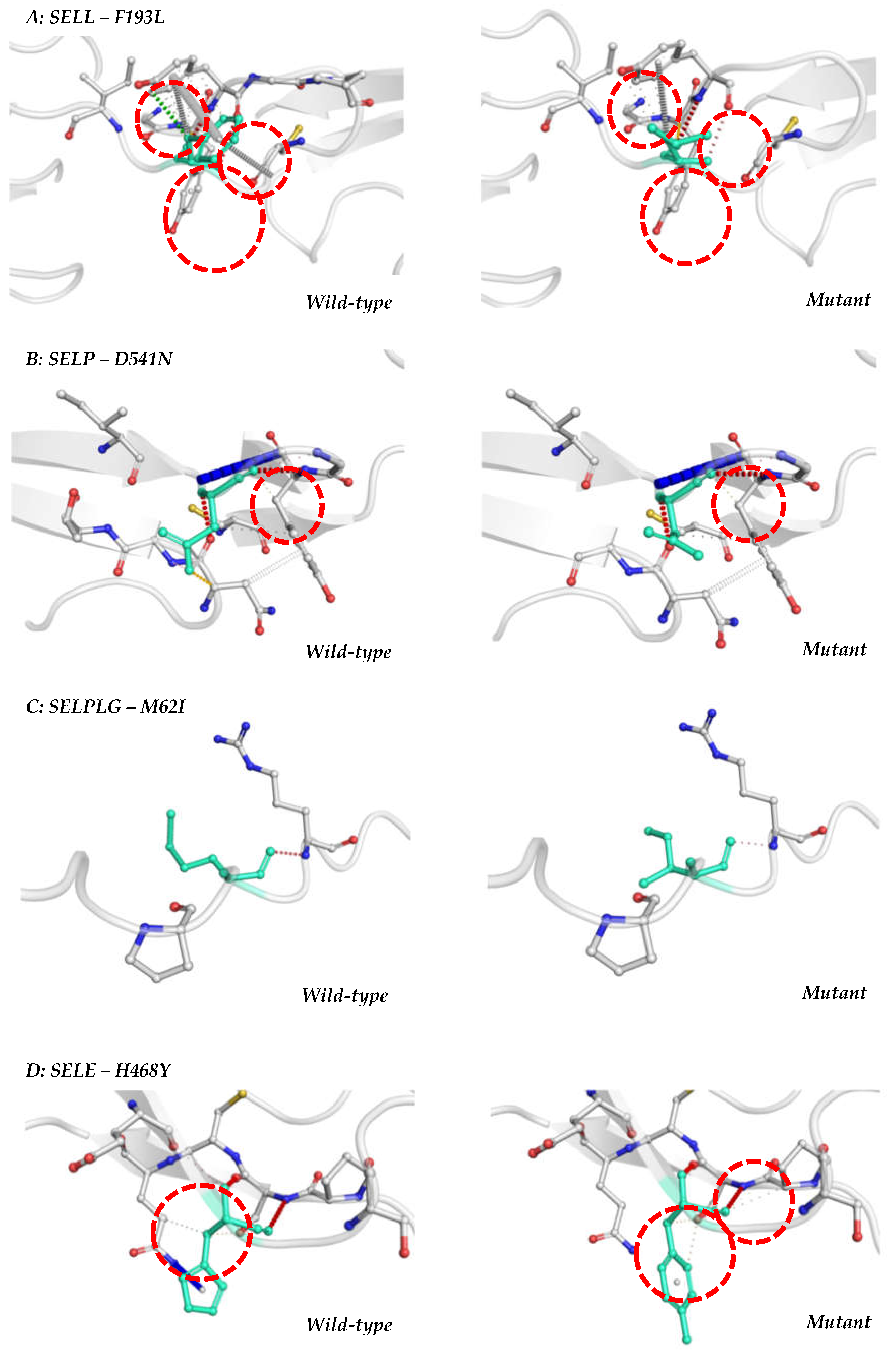

3.1. L-selectin (SELL gene)

3.2. P-selectin (SELP gene)

3.3. PSGL-1 (SELPLG gene)

3.4. E-selectin (SELE gene)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Tomso, D.J.; Liu, X.; Bell, D.A. Single nucleotide polymorphism in transcriptional regulatory regions and expression of environmentally responsive genes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 207, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, K.M.; Brett, C.M.; Altman, R.B.; Benowitz, N.L.; Dolan, M.E.; Flockhart, D.A.; Johnson, J.A.; Hayes, D.F.; Klein, T.; Krauss, R.M.; et al. The pharmacogenetics research network: from SNP discovery to clinical drug response. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 81, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargill, M.; Altshuler, D.; Ireland, J.; Sklar, P.; Ardlie, K.; Patil, N.; Shaw, N.; Lane, C.R.; Lim, E.P.; Kalyanaraman, N.; et al. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes. Nat Genet 1999, 22, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Schwartz, C.E.; Alexov, E.; Wang, L. Structural assessment of the effects of amino acid substitutions on protein stability and protein protein interaction. Int J Comput Biol Drug Des 2010, 3, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukkal, T.G.; Petukh, M.; Li, L.; Alexov, E. Structural and physico-chemical effects of disease and non-disease nsSNPs on proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015, 32, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buroker, N.E. Regulatory SNPs and transcriptional factor binding sites in ADRBK1, AKT3, ATF3, DIO2, TBXA2R and VEGFA. Transcription 2014, 5, e964559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birney, E.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; Dutta, A.; Guigó, R.; Gingeras, T.R.; Margulies, E.H.; Weng, Z.; Snyder, M.; Dermitzakis, E.T.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 2007, 447, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangbam, C.S.; Qualls, C.W., Jr.; Dahlgren, R.R. Cell adhesion molecules--update. Veterinary pathology 1997, 34, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.S. L-Selectin (CD62L) and Its Ligands. In Animal Lectins: Form, Function and Clinical Applications; Springer Vienna: Vienna, 2012; pp. 553–574. [Google Scholar]

- Raffler, N.A.; Rivera-Nieves, J.; Ley, K. L-selectin in inflammation, infection and immunity. Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies 2005, 2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Martins, P.; van den Berk, N.; Ulfman, L.H.; Koenderman, L.; Hordijk, P.L.; Zwaginga, J.J. Platelet-monocyte complexes support monocyte adhesion to endothelium by enhancing secondary tethering and cluster formation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2004, 24, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S.D.; Bertozzi, C.R. The selectins and their ligands. Current opinion in cell biology 1994, 6, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubli, H.; Borsig, L. Selectins promote tumor metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol 2010, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniluk, A.; Kaminska, J.; Kiszlo, P.; Kemona, H.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V. Lectin adhesion proteins (P-, L- and E-selectins) as biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Biomarkers 2017, 22, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S.D. Ligands for L-selectin: homing, inflammation, and beyond. Annual review of immunology 2004, 22, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEver, R.P. Selectins: initiators of leucocyte adhesion and signalling at the vascular wall. Cardiovascular research 2015, 107, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivetic, A.; Hoskins Green, H.L.; Hart, S.J. L-selectin: A Major Regulator of Leukocyte Adhesion, Migration and Signaling. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, K.; Laudanna, C.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Nourshargh, S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.; Hegde, P.; Voznesensky, O.; Choudhary, S.; Kopsiaftis, S.; Claffey, K.P.; Pilbeam, C.C.; Taylor, J.A. , 3rd. Increased expression of L-selectin (CD62L) in high-grade urothelial carcinoma: A potential marker for metastatic disease. Urologic oncology 2015, 33, 387–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobawala, T.P.; Trivedi, T.I.; Gajjar, K.K.; Patel, D.H.; Patel, G.H.; Ghosh, N.R. Significance of TNF-alpha and the Adhesion Molecules: L-Selectin and VCAM-1 in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. J Thyroid Res 2016, 2016, 8143695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzza, M.; Degl'Innocenti, D.; Colombo, C.; Perrino, M.; Ravasi, E.; Rossi, S.; Cirello, V.; Beck-Peccoz, P.; Borrello, M.G.; Fugazzola, L. The tight relationship between papillary thyroid cancer, autoimmunity and inflammation: clinical and molecular studies. Clinical endocrinology 2010, 72, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, N.; d'Agua, B.B.; Ridley, A.J. Crossing the endothelial barrier during metastasis. Nature reviews. Cancer 2013, 13, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Boelte, K.C.; Lin, P.C. Endothelial cell adhesion molecules and cancer progression. Current medicinal chemistry 2007, 14, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasti, T.H.; Bullard, D.C.; Yusuf, N. P-selectin enhances growth and metastasis of mouse mammary tumors by promoting regulatory T cell infiltration into the tumors. Life Sci 2015, 131, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, U.; Schröder, C.; Wicklein, D.; Lange, T.; Geleff, S.; Dippel, V.; Schumacher, U.; Klutmann, S. Adhesion of small cell lung cancer cells to E- and P-selectin under physiological flow conditions: implications for metastasis formation. Histochem Cell Biol 2011, 135, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celi, A.; Pellegrini, G.; Lorenzet, R.; De Blasi, A.; Ready, N.; Furie, B.C.; Furie, B. P-selectin induces the expression of tissue factor on monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 8767–8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalbach, B.; Stepanow, O.; Jochens, A.; Riedel, C.; Deuschl, G.; Kuhlenbäumer, G. Determinants of platelet-leukocyte aggregation and platelet activation in stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015, 39, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powrózek, T.; Mlak, R.; Brzozowska, A.; Mazurek, M.; Gołębiowski, P.; Małecka-Massalska, T. Relationship Between -2028 C/T SELP Gene Polymorphism, Concentration of Plasma P-Selectin and Risk of Malnutrition in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Pathol Oncol Res 2019, 25, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis, J.M.; Viramontes, K.M.; Neubert, E.N.; Tinoco, R. PSGL-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for CD4(+) T Cell Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 636238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoos, A.; Protsyuk, D.; Borsig, L. Metastatic growth progression caused by PSGL-1-mediated recruitment of monocytes to metastatic sites. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrati, C.; Sacchi, A.; Tartaglia, E.; Vergori, A.; Gagliardini, R.; Scarabello, A.; Bibas, M. The Role of P-Selectin in COVID-19 Coagulopathy: An Updated Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis, J.M.; Viramontes, K.M.; Neubert, E.N.; Henriquez, M.L.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Tinoco, R. Targeting the PSGL-1 Immune Checkpoint Promotes Immunity to PD-1-Resistant Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2022, 10, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, R.; Otero, D.C.; Takahashi, A.A.; Bradley, L.M. PSGL-1: A New Player in the Immune Checkpoint Landscape. Trends Immunol 2017, 38, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Abt, M.; Ciorciaro, C.; Kling, D.; Jamois, C.; Schick, E.; Solier, C.; Benghozi, R.; Gaudreault, J. First-in-Man Study With Inclacumab, a Human Monoclonal Antibody Against P-selectin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2015, 65, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsaeva, D.R.; Parkerson, J.B.; Yerigenahally, S.D.; Kurz, J.C.; Schaub, R.G.; Ikuta, T.; Head, C.A. Inhibition of cell adhesion by anti-P-selectin aptamer: a new potential therapeutic agent for sickle cell disease. Blood 2011, 117, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, P.; Maes, A.; Nuyts, J.; Belmans, A.; Desmet, W.; Esplugas, E.; Charlier, F.; Figueras, J.; Sambuceti, G.; Schwaiger, M.; et al. Recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-immunoglobulin, a P-selectin antagonist, as an adjunct to thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. The P-Selectin Antagonist Limiting Myonecrosis (PSALM) trial. Am Heart J 2006, 152, 125–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.S.; Miranda-Nieves, D.; Chen, J.; Haller, C.A.; Chaikof, E.L. Targeting P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1/P-selectin interactions as a novel therapy for metabolic syndrome. Transl Res 2017, 183, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muz, B.; Azab, F.; de la Puente, P.; Rollins, S.; Alvarez, R.; Kawar, Z.; Azab, A.K. Inhibition of P-Selectin and PSGL-1 Using Humanized Monoclonal Antibodies Increases the Sensitivity of Multiple Myeloma Cells to Bortezomib. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 417586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleisa, F.A.; Sakashita, K.; Lee, J.M.; AbuSamra, D.B.; Al Alwan, B.; Nozue, S.; Tehseen, M.; Hamdan, S.M.; Habuchi, S.; Kusakabe, T.; et al. Functional binding of E-selectin to its ligands is enhanced by structural features beyond its lectin domain. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 3719–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, B.F.; Almohaidi, A.M.S.; Şimşek, S.A.; Al-Waysi, S.A.; Al-Dabbagh, W.H.; Kamal, A.M. The relationship of E-selectin singlenucleotide polymorphisms with breast cancer in Iraqi Arab women. Genomics Inform 2022, 20, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziltunc Ozmen, H.; Simsek, M. Serum IL-23, E-selectin and sICAM levels in non-small cell lung cancer patients before and after radiotherapy. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520923493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, P.E.; Miró, L.; Wong, B.S.; Massaguer, A.; Martínez-Bosch, N.; Llorens, R.; Navarro, P.; Konstantopoulos, K.; Llop, E.; Peracaula, R. Knockdown of α2,3-Sialyltransferases Impairs Pancreatic Cancer Cell Migration, Invasion and E-selectin-Dependent Adhesion. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanio, M.; Muramoto, A.; Hoshino, H.; Murahashi, M.; Imamura, Y.; Yokoyama, O.; Kobayashi, M. Expression of functional E-selectin ligands on the plasma membrane of carcinoma cells correlates with poor prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2021, 39, 302–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, T.U. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendl, J.; Musil, M.; Štourač, J.; Zendulka, J.; Damborský, J.; Brezovský, J. PredictSNP2: A Unified Platform for Accurately Evaluating SNP Effects by Exploiting the Different Characteristics of Variants in Distinct Genomic Regions. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12, e1004962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, M.; Witten, D.M.; Jain, P.; O'Roak, B.J.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, D.; Chen, Y.; Xie, X. DANN: a deep learning approach for annotating the pathogenicity of genetic variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihab, H.A.; Rogers, M.F.; Gough, J.; Mort, M.; Cooper, D.N.; Day, I.N.; Gaunt, T.R.; Campbell, C. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lou, S.; Bedford, J.; Mu, X.J.; Yip, K.Y.; Khurana, E.; Gerstein, M. FunSeq2: a framework for prioritizing noncoding regulatory variants in cancer. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, G.R.; Dunham, I.; Zeggini, E.; Flicek, P. Functional annotation of noncoding sequence variants. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendl, J.; Stourac, J.; Salanda, O.; Pavelka, A.; Wieben, E.D.; Zendulka, J.; Brezovsky, J.; Damborsky, J. PredictSNP: robust and accurate consensus classifier for prediction of disease-related mutations. PLoS Comput Biol 2014, 10, e1003440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, P.C.; Henikoff, S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31, 3812–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramensky, V.; Bork, P.; Sunyaev, S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 3894–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.A.; Sidow, A. Physicochemical constraint violation by missense substitutions mediates impairment of protein function and disease severity. Genome Res 2005, 15, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capriotti, E.; Calabrese, R.; Casadio, R. Predicting the insurgence of human genetic diseases associated to single point protein mutations with support vector machines and evolutionary information. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 2729–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberg, Y.; Rost, B. SNAP: predict effect of non-synonymous polymorphisms on function. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 3823–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunham, L.R.; Singaraja, R.R.; Pape, T.D.; Kejariwal, A.; Thomas, P.D.; Hayden, M.R. Accurate prediction of the functional significance of single nucleotide polymorphisms and mutations in the ABCA1 gene. PLoS Genet 2005, 1, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Zhou, M.; Cui, Y. nsSNPAnalyzer: identifying disease-associated nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Randall, A.; Baldi, P. Prediction of protein stability changes for single-site mutations using support vector machines. Proteins 2006, 62, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T. Cancer metastasis: characterization and identification of the behavior of metastatic tumor cells and the cell adhesion molecules, including carbohydrates. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 2005, 5, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpathiou, G.; Sramek, V.; Dagher, S.; Mobarki, M.; Dridi, M.; Picot, T.; Chauleur, C.; Peoc'h, M. Peripheral node addressin, a ligand for L-selectin is found in tumor cells and in high endothelial venules in endometrial cancer. Pathol Res Pract 2022, 233, 153888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jóźwik, M.; Okungbowa, O.E.; Lipska, A.; Jóźwik, M.; Smoktunowicz, M.; Semczuk, A.; Jóźwik, M.; Radziwon, P. Surface antigen expression on peripheral blood monocytes in women with gynecologic malignancies. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Arora, M.; Singh, J.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, S.; Chopra, A. L-Selectin expression is associated with inflammatory microenvironment and favourable prognosis in breast cancer. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Changfu, W.; Linyun, L.; Bing, M.; Xiaohui, H. Correlations of platelet-leukocyte aggregates with P-selectin S290N and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 M62I genetic polymorphisms in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 2016, 367, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosan, F.; Oku, B.; Gedar Totuk, O.M.; Abaci, N.; Ustek, D.; Diz Kucukkaya, R.; Gul, A. The association between P selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 gene variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism and risk of thrombosis in Behçet's disease. Int J Rheum Dis 2018, 21, 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, J.; Kapoor, R.; Kaur, M. Association of SELP Polymorphisms with Soluble P-Selectin Levels and Vascular Risk in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Case-Control Study. Biochem Genet 2019, 57, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avan, A.; Avan, A.; Le Large, T.Y.; Mambrini, A.; Funel, N.; Maftouh, M.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Cantore, M.; Boggi, U.; Peters, G.J.; et al. AKT1 and SELP polymorphisms predict the risk of developing cachexia in pancreatic cancer patients. PLoS One 2014, 9, e108057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, E.; Freitas, R.; Ferreira, D.; Soares, J.; Azevedo, R.; Gaiteiro, C.; Peixoto, A.; Oliveira, S.; Cotton, S.; Relvas-Santos, M.; et al. Nucleolin-Sle A Glycoforms as E-Selectin Ligands and Potentially Targetable Biomarkers at the Cell Surface of Gastric Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmos, A.B.; Millischer, V.; Menon, D.K.; Nicholson, T.R.; Taams, L.S.; Michael, B.; Sunderland, G.; Griffiths, M.J.; Hübel, C.; Breen, G. Proteome-wide Mendelian randomization identifies causal links between blood proteins and severe COVID-19. PLoS Genet 2022, 18, e1010042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xiao, H.; Shen, J.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.D. SELE gene as a characteristic prognostic biomarker of colorectal cancer. J Int Med Res 2021, 49, 3000605211004386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribieras, A.J.; Ortiz, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Huerta, C.T.; Le, N.; Shao, H.; Vazquez-Padron, R.I.; Liu, Z.J.; Velazquez, O.C. E-Selectin/AAV2/2 Gene Therapy Alters Angiogenesis and Inflammatory Gene Profiles in Mouse Gangrene Model. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 929466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz, H.J.; Parikh, P.P.; Lassance-Soares, R.M.; Regueiro, M.M.; Li, Y.; Shao, H.; Vazquez-Padron, R.; Percival, J.; Liu, Z.J.; Velazquez, O.C. Gangrene, revascularization, and limb function improved with E-selectin/adeno-associated virus gene therapy. JVS Vasc Sci 2021, 2, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Yu, C.; Wang, P.; Shi, Y.; Cao, W.; Cheng, B.; Chapla, D.G.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Rodrigues, E.; et al. Glycoengineering of NK Cells with Glycan Ligands of CD22 and Selectins for B-Cell Lymphoma Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021, 60, 3603–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turpin, A.; Labreuche, J.; Fléjou, J.F.; Andre, T.; de Gramont, A.; Hebbar, M. Prognostic factors in patients with stage II colon cancer: Role of E-selectin gene polymorphisms. Dig Liver Dis 2019, 51, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeAngelo, D.J.; Jonas, B.A.; Liesveld, J.L.; Bixby, D.L.; Advani, A.S.; Marlton, P.; Magnani, J.L.; Thackray, H.M.; Feldman, E.J.; O'Dwyer, M.E.; et al. Phase 1/2 study of uproleselan added to chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2022, 139, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamil, B.D.; Thurman, G.B.; Sundell, H.W.; DeVore, R.F.; Wakefield, G.; Johnson, D.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Hellerqvist, C.G. Soluble E-selectin in cancer patients as a marker of the therapeutic efficacy of CM101, a tumor-inhibiting anti-neovascularization agent, evaluated in phase I clinical trail. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1997, 123, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paluri, R.; Madan, A.; Li, P.; Jones, B.; Saleh, M.; Jerome, M.; Miley, D.; Keef, J.; Robert, F. Phase 1b trial of nintedanib in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2019, 83, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dampier, C.D.; Telen, M.J.; Wun, T.; Brown, R.C.; Desai, P.; El Rassi, F.; Fuh, B.; Kanter, J.; Pastore, Y.; Rothman, J.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of rivipansel for sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis. Blood 2023, 141, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qiu, R.; Abudoubari, S.; Tao, N.; An, H. Effect of interaction between occupational stress and polymorphisms of MTHFR gene and SELE gene on hypertension. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayat, S.; Ramezanidoraki, N.; Kazemi, N.; Modarressi, M.H.; Falah, M.; Zardadi, S.; Morovvati, S. Association study between polymorphisms in MIA3, SELE, SMAD3 and CETP genes and coronary artery disease in an Iranian population. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2022, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, B.; Sayin, T.; Akbas, H.; Gokmen, E.S.; Atay, A.E.; Guzel, S.P.; Gorgulu, N.; Yavuz, D.G. The role of serum E-selectin level and E-selectin gene S128R polymorphism on the enlargement of renal cyst in patients with polycystic kidney disease: Genetic background of renal cyst growth Clin Nephrol 2020, 93, 34-49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Cheng, J.H.; Nie, Z.C.; Ding, B.S.; Han, Z.; Zheng, W.W. Association of E-Selectin Gene +A561C Polymorphism with Type 2 Diabetes in Chinese Population. Clin Lab 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R.; El Bannoudi, H.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Bornkamp, N.; Allen, N.; Dann, R.; Reynolds, H.; Buyon, J.P.; Berger, J.S. Human low-affinity IgG receptor FcγRIIA polymorphism H131R associates with subclinical atherosclerosis and increased platelet activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Thromb Haemost 2019, 17, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | ID | Ref | Alt | Classification | PredictSNP2.0 | CADD | DANN | FATHMM | FUNSEQ2 | GWAVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SELL Chr #1 |

169695726 | rs4987360 | A | G | intronic | D | D | D | ? | D | N |

| 169704697 | rs2229569 | G | A | exonic | D | D | D | D | N | ? | |

| 169706069 | rs4987301 | G | A | intronic | D | D | D | D | D | N | |

| 169706069 | rs4987301 | G | T | intronic | D | D | D | D | D | N | |

| 169707345 | rs1131498 | A | G | exonic | N | D | N | N | N | N | |

| 169712216 | rs2205849 | T | C | upstream | D | D | D | D | D | D | |

|

SELP Chr #1 |

169596108 | rs6133 | C | A | exonic | N | N | N | D | N | D |

| 169596108 | rs6133 | C | G | exonic | N | N | N | D | N | D | |

| 169597075 | rs6127 | C | G | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | ? | |

| 169597075 | rs6127 | C | T | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | ? | |

| 169601781 | rs3917777 | T | A | intronic | D | D | D | ? | D | N | |

| 169601781 | rs3917777 | T | C | intronic | D | D | ? | ? | D | N | |

| 169601781 | rs3917777 | T | G | intronic | D | D | D | ? | D | N | |

| 169605484 | rs2205894 | T | A | intronic | D | D | D | D | ? | N | |

| 169605484 | rs2205894 | T | G | intronic | D | D | D | D | ? | N | |

| 169605486 | rs2205893 | T | A | intronic | D | D | D | D | ? | N | |

| 169605486 | rs2205893 | T | G | intronic | D | D | D | D | ? | N | |

| 169611647 | rs6131 | C | T | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

|

SELPLG Chr #12 |

108623488 | rs7300972 | T | A | exonic | N | N | N | N | D | D |

| 108623488 | rs7300972 | T | C | exonic | N | N | N | N | D | D | |

| 108623898 | rs201851784 | A | G | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | D | |

| 108623898 | rs201851784 | A | T | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | D | |

| 108624122 | rs2228315 | C | T | exonic | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| 108628692 | rs7138370 | G | A | intronic | N | D | D | N | D | D | |

|

SELE Chr #1 |

169727805 | rs5368 | G | A | exonic | N | N | N | N | D | D |

| 169729684 | rs1534904 | T | A | intronic | D | D | D | ? | D | N | |

| 169729684 | rs1534904 | T | G | intronic | N | D | N | N | D | N |

| Gene | ID | AA Change | PredictSNP1.0 | MAPP | PhD-SNP | PolyPhen-1 | PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | SNAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELL | rs1131498 | F193L | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| rs2229569 | P213S | N | D | N | N | N | N | N | |

| rs2229569 | P213T | N | D | D | N | N | D | N | |

| SELP | rs6131 | S331N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| rs6127 | D541N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| SELPLG | rs2228315 | M62I | N | N | N | D | N | N | N |

| rs201851784 | V137A | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| rs7300972 | M274V | N | D | N | N | N | D | N | |

| SELE | rs5368 | H468Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).