Submitted:

22 February 2023

Posted:

01 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

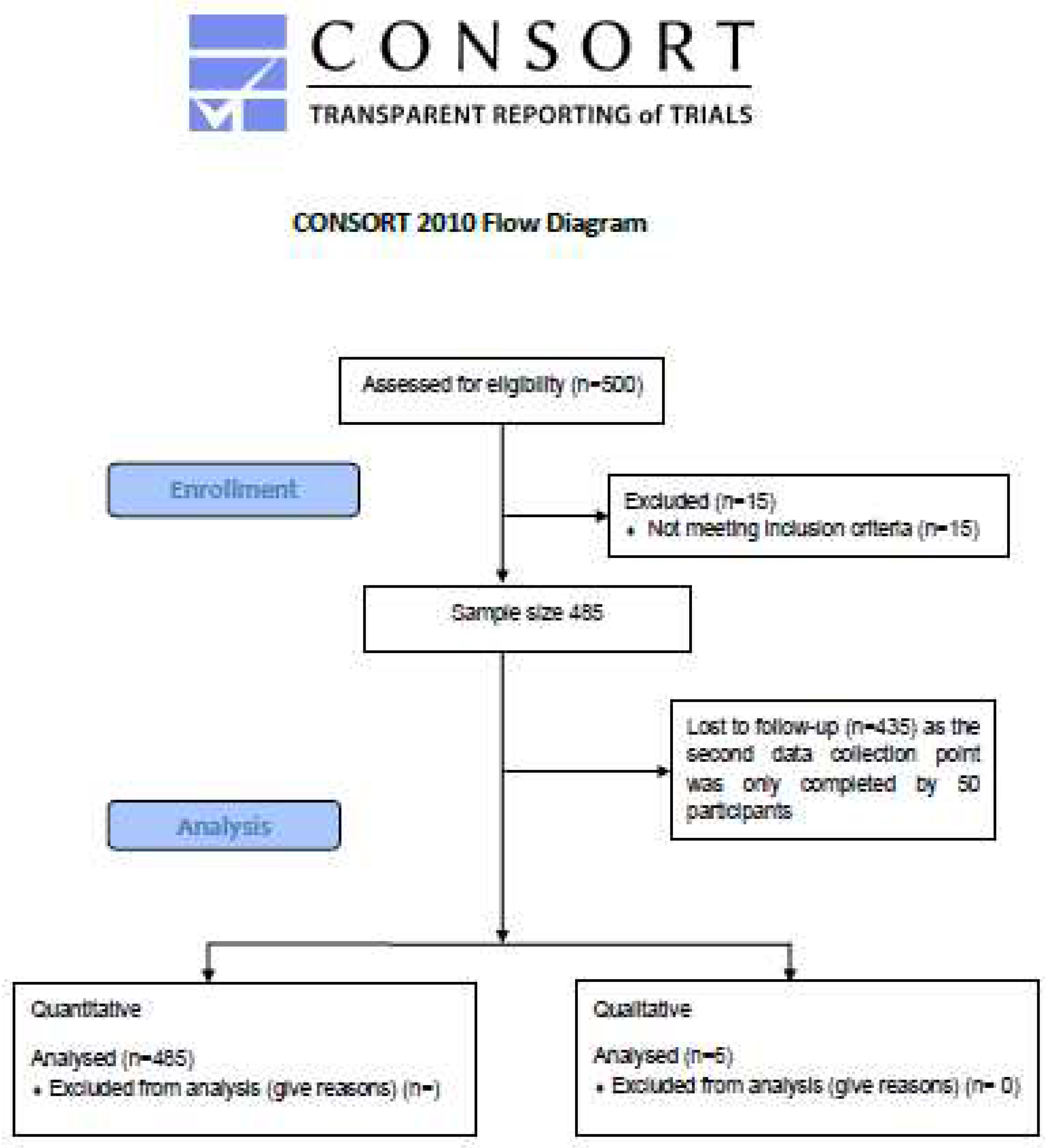

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Analysis Plan

2.5.1. Quantitative

2.5.2. Qualitative

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

3.2. Age

| Anxiety level | 18 - 24 | 25 - 34 | 35 - 44 | 45 - 54 | 55 - 64 | 65 and over |

| Abnormal | 2 | 21 | 34 | 37 | 20 | 7 |

| Borderline abnormal | 3 | 27 | 37 | 31 | 17 | 5 |

| Normal | 0 | 5 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 4 |

| Total | 5 | 53 | 85 | 82 | 45 | 16 |

|

Chi-Squared Test: .8092 |

||||||

3.3. Gender

| Anxiety level | Male | Female |

| Abnormal | 9 | 110 |

| Borderline abnormal | 29 | 92 |

| Normal | 10 | 35 |

| Total | 48 | 237 |

|

Chi-Square Test 0.001808* |

| BAT-12 | HADS | Everyday discrimination | ISI | GSE | VIA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Exhaustion | Mental distance | Cognitive impairment | Emotional impairment | Anxiety | Depression | Heritage | Mainstream | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 356 | 8.7 (2.7) | 7.3 (2.9) | 8.1 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.4) | 10.4 (2.6) | 8.4 (1.7) | 0.8 (0.7) | 8.1 (5.8) | 3.0 (0.5) | 6.44 (1.47) | 6.60 (1.44) |

| Male | 75 | 7.8 (2.7) | 7.5 (2.6) | 7.9 (2.8) | 5.2 (2.1) | 9.2 (2.5) | 8.4 (1.5) | 0.8 (0.6) | 6.7 (6.1) | 3.1 (0.4) | 5.99 (1.46) | 6.20 (1.56) |

| T-test | 0.041* | 0.607 | 0.667 | 0.445 | 0.002* | 0.986 | 0.965 | 0.149 | 0.548 | 0.060* | 0.092* | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18 - 24 | 11 | 10.2 (4.3) | 7.7 (3.3) | 8.3 (3.3) | 5.7 (2.4) | 10.4 (2.7) | 9.5 (2.9) | 0.9 (0.7) | 10.2 (8.1) | 2.8 (0.6) | 6.21 (1.05) | 6.09 (1.58) |

| 25 - 34 | 90 | 8.7 (2.8) | 7.2 (2.8) | 7.7 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.5) | 9.8 (2.4) | 8.2 (1.6) | 0.7 (0.7) | 7.7 (6.6) | 3.1 (0.4) | 6.38 (1.49) | 6.65 (1.27) |

| 35 - 44 | 131 | 8.6 (2.7) | 7.6 (3.0) | 8.6 (2.6) | 5.4 (2.4) | 9.7 (3.2) | 8.1 (1.7) | 0.8 (0.7) | 6.8 (5.7) | 3.0 (0.5) | 6.31 (1.46) |

6.44 (1.44) |

| 45 - 54 | 115 | 8.8 (2.6) | 7.8 (2.8) | 8.2 (2.5) | 5.9 (2.7) | 10.4 (2.7) | 8.6 (1.6) | 0.9 (0.7) | 8.6 (5.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | 6.27 (1.45) | 6.41 (1.53) |

| 55 - 64 | 70 | 7.8 (2.7) | 6.9 (2.8) | 7.3 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.0) | 9.8 (2.4) | 8.9 (1.6) | 0.6 (0.6) | 8.2 (5.6) | 3.1 (0.4) | 6.38 (1.67) | 6.64 (1.54) |

| > 64 | 21 | 8.1 (3.2) | 5.7 (2.2) | 7.1 (2.4) | 5.2 (1.7) | 9.7 (3.2) | 9.0 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.4) | 8.6 (6.2) | 3.3 (0.4) | 7.51 (1.37) | 7.80 (1.47) |

| ANOVA | 0.276 | 0.147 | 0.042* | 0.521 | 0.699 | 0.016* | 0.054* | 0.376 | 0.070* | 0.213 | 0.089* | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White British | 340 | 8.5 (2.6) | 7.3 (2.8) | 8.2 (2.4) | 5.4 (2.3) | 10.1 (2.5) | 8.5 (1.7) | 0.7 (0.6) | 7.9 (5.9) | 3.0 (0.4) | 6.25 (1.50) | 6.52 (1.49) |

| Other ethnicity | 67 | 8.8 (3.0) | 7.2 (3.1) | 7.8 (2.8) | 5.7 (2.8) | 10.9 (2.8) | 8.2 (1.7) | 0.9 (0.8) | 8.4 (5.8) | 3.0 (0.6) | 6.78 (1.30) | 6.59 (1.29) |

| T-test | 0.562 | 0.806 | 0.403 | 0.460 | 0.078* | 0.193 | 0.223 | 0.638 | 0.570 | 0.020* | 0.751 | |

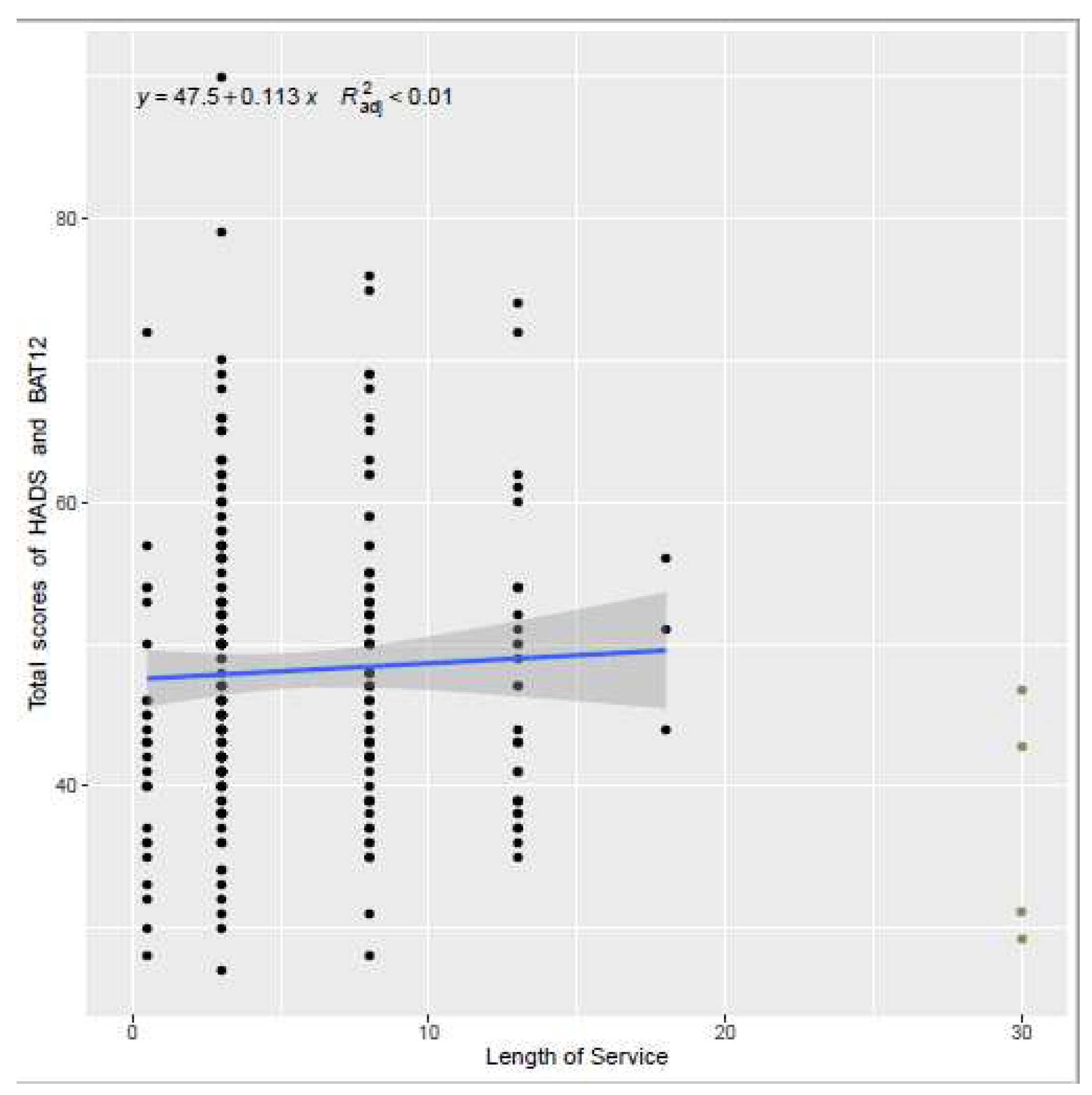

| Length of service | ||||||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 50 | 7.7 (2.9) | 5.8 (2.3) |

7.0 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.1) | 9.7 (2.3) |

8.4 (1.8) | 0.7 (0.6) | 7.7 (6.6) |

3.1 (0.4) | 6.36 (1.81) |

6.39 (1.76) |

| 1 to 5 years | 192 | 8.7 (2.7) | 7.9 (2.8) |

8.2 (2.3) | 5.6 (2.5) | 10.2 (2.7) | 8.4 (1.7) | 0.8 (0.7) | 7.9 (5.9) |

3.0 (0.4) | 6.35 (1.36) |

6.57 (1.34) |

| 6 to 10 years | 105 | 8.7 (2.7) | 7.3 (2.9) |

8.3 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.5) | 10.7 (2.7) | 8.5 (1.6) | 0.8 (0.7) | 7.8 (5.6) |

3.1 (0.5) | 6.37 (1.56) |

6.52 (1.58) |

| 11 to 15 years | 47 | 8.8 (2.9) | 7.2 (2.7) |

8.1 (2.6) | 5.3 (2.6) | 9.8 (2.0) |

8.4 (1.9) | 0.7 (0.5) | 8.3 (6.2) |

3.1 (0.6) | 6.17 (1.41) |

6.23 (1.42) |

| 16 to 20 years | 7 | 9.3 (1.3) | 8.0 (1.4) |

7.8 (2.1) | 6.3 (0.6) | 12.2 (3.6) | 8.6 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.2) | 6.6 (2.9) |

3.0 (0.2) | 7.12 (2.00) |

7.62 (1.43) |

| Over 21 years | 10 | 6.6 (3.8) | 3.4 (0.9) |

4.6 (1.8) | 4.0 (1.4) | 8.8 (2.7) |

9.5 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.4) | 9.3 (6.8) |

3.0 (0.3) | 6.72 (1.59) |

6.76 (1.57) |

| ANOVA | 0.329 | <0.001* | 0.008* | 0.363 | 0.106 | 0.744 | 0.690 | 0.978 | 0.830 | 0.852 | 0.504 | |

| Professional groups | ||||||||||||

| Trial management | 127 | 8.4 (2.5) | 7.4 (2.8) |

8.4 (2.8) | 5.4 (2.3) | 7.9 (4.3) |

4.8 (3.6) | 0.8 (0.7) | 7.1 (5.5) |

3.1 (0.5) | ||

| Quality assurance | 8 | 9.0 (1.9) | 7.1 (1.8) |

8.7 (2.0) | 4.4 (1.3) | 8.7 (4.6) |

3.5 (4.0) | 0.9 (0.6) | 10.3 (8.3) | 3.0 (0.2) | ||

| Database management | 34 | 8.5 (3.0) | 7.2 (3.0) |

8.3 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.7) | 8.0 (3.9) |

5.3 (4.0) | 0.7 (0.6) | 9.1 (6.9) |

2.8 (0.6) | ||

| Doctor/Nur se | 34 | 8.8 (3.1) | 7.1 (2.9) |

7.7 (2.6) | 6.2 (3.0) | 8.9 (4.2) |

5.9 (4.3) | 0.9 (0.8) | 8.5 (5.7) | 3.0 (0.3) | ||

| Statistician | 29 | 9.2 (3.1) | 7.8 (2.8) |

7.8 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.7) | 8.6 (4.4) |

6.1 (4.7) | 0.5 (0.7) | 6.5 (5.2) | 3.1 (0.4) | ||

| ANOVA | 0.851 | 0.965 | 0.723 | 0.364 | 0.820 | 0.480 | 0.409 | 0.368 | 0.209 | |||

3.4. Mental health Assessment

3.4.1. Length of Service

3.4.2. Well-Being

3.4.3. Professional Group Outcomes

| Demographics - Questionnaire respondents (N = 127) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N(%) | Variables | N(%) | ||

| Age |

18 - 24 1 (0.8%) 25 - 34 23 (18.1%) 35 - 44 46 (36.2%) 45 - 54 35 (27.6%) 55 - 64 17 (13.4%) 65 and over 5 (3.9%) |

Religion | Christian 33 (26.0%) Muslim 7 (5.5%) Hindu 1 (0.8%) Buddhist 1 (0.8%) No religion 83 (65.4%) Other 1 (0.8%) Not available 1 (0.8%) |

||

| Gender |

Female 105 (82.7%) Male 22 (17.3%) |

Ethnicity |

Asian 2 (1.6%) Indian 1 (0.8%) Bangladeshi 2 (1.6%) Pakistani 2 (1.6%) White & Asian 1 (0.8%) White & Caribbean 1 (0.8%) White British 100 (78.7%) Other background 11 (8.7%) Not available 7 (5.5%) |

||

| Nationality |

United Kingdom 77 (60.6%) Not available 50 (39.4%) |

||||

| Health and wellbeing | |||||

| Suffer from any long- term conditions | Yes 36 (28.3%) No 83 (65.4%) Prefer not to say 1 (0.8%) Not available 7 (5.5%) |

Suffer from any disabilities | Yes 5 (3.9%) No 113 (89.0%) Prefer not to say 2 (1.6%) Not available 7 (5.5%) |

||

| Taking medication for any mental health condition | Yes 20 (15.7%) No 100 (78.7%) Not available 7 (5.5%) |

Taking medication for any physical condition | Yes 32 (25.2%) No 86 (67.7%) Prefer not to say 2 (1.6%) Not available 7 (5.5%) |

||

|

Mental health rating since the pandemic began |

Much better 2(1.6%) Somewhat better 9 (7.1%) About the same 45 (35.4%) Somewhat worse 54 (42.5%) Much worse 9 (7.1%) Not available 8 (6.3%) |

Physical health rating since the pandemic began | Much better 3 (2.4%) Somewhat better 13 (10.2%) About the same 58 (45.7%) Somewhat worse 39 (30.7%) Much worse 6 (4.7%) Not available 8 (6.3%) |

||

|

Test positive for COVID-19 in the past 12 months |

Yes 12 (9.4%) No 107 (78.7%) Not available 8 (6.3%) |

||||

| Demographics | Questionnaire respondents (N = 8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N(%) | Variables | N(%) |

| Age | 25 - 34 2 (25.0%) 35 - 44 2 (25.0%) 45 - 54 3 (37.5%) 55 - 64 1 (12.5%) |

Religion | Christian 3 (37.5%) No religion 5 (62.5%) Female 6 (75.0%) Male 2 (25.0%) |

| Gender | |||

| Nationality Health and wellbeing Suffer from any long-term conditions |

United Kingdom 7 (87.5%) Not available 1 (12.5%) |

Ethnic Suffer from any disabilities |

White British 8 (100.0%) No 8 (100.0%) |

| Yes 2 (25.0%) No 6 (75.0%) | |||

|

Taking medication for any mental health condition Mental health rating since the pandemic began Test positive for COVID-19 in the past 12 months |

Yes 1 (12.5%) No 7 (87.5%) |

Taking medication for any physical condition Physical health rating since the pandemic began |

Yes 2 (25.0%) No 6 (75.0%) Somewhat better 2 (25.0%) About the same 5 (62.5%) Somewhat worse 1 (12.5%) |

| Somewhat better 1 (12.5%) About the same 3 (37.5%) Somewhat worse 2 (25.0%) Much worse 2 (25.0%) | |||

| No 8 (100.0%) |

3.4.4. Ethnicity

| Severity | Mean (SD) | Item-total r |

|---|---|---|

| Initial (Difficulty falling asleep) sleep onset | 0.99 (1.10) | 0.5456 |

| Middle (Difficulty staying asleep) sleep maintenance | 1.18 (1.12) | 0.7461 |

| Terminal (Problem waking up too early) | 1.16 (1.19) | 0.6095 |

| Satisfaction | 1.87 (1.20) | 0.7554 |

| Interference | 1.08 (1.02) | 0.7758 |

| Noticeability | 0.90 (1.00) | 0.7232 |

| Distress (Worried) | 0.70 (0.84) | 0.7579 |

| Total | 7.88 (5.86) |

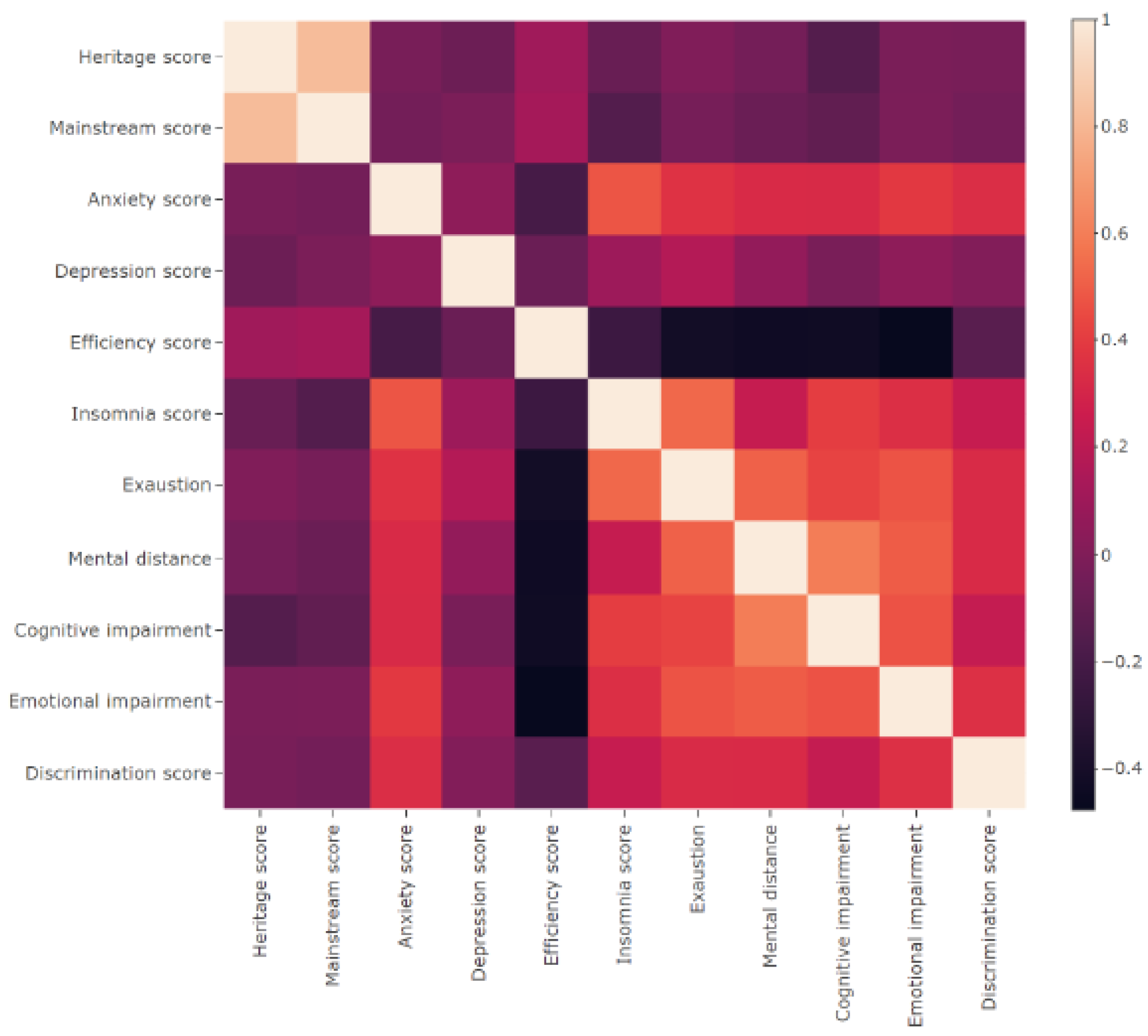

3.4.5. Heat-Map Correlation

3.4.6. Linear Regression

Item-Total Correlations of ISI

| Scale information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA) | |||

| Heritage score | 6.36 / 9 (1.48) | Mainstream score | 6.53 / 9 (1.47) |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | |||

| Anxiety score | 10.24 / 21 (2.60) | Depression score | 8.46 / 21 (1.69) |

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | |||

| Insomnia score | 7.88 / 28 (5.86) | ||

| Pandemic Stress Index (PSI) | |||

| Behavioral experiences during COVID-19 | No changes to my life or behaviour | 3 (0.62%) | |

| Practicing social distancing | 278 (57.32%) | ||

| Isolating or quarantine yourself | 154 (31.75%) | ||

| Caring for someone at home | 43 (8.87%) | ||

| Working from home | 268 (55.26%) | ||

| Not working | 8 (1.65%) | ||

| A change in use of healthcare services | 107 (22.06%) | ||

| Following media coverage related to COVID-19 | 233 (48.04%) | ||

| Changing travel plans | 207 (42.68%) | ||

| Impact of COVID-19 on day-to-day life | Not at all | 4 (0.82%) | |

| A little | 50 (10.31%) | ||

| Much | 66 (13.61%) | ||

| Very Much | 93 (19.18%) | ||

| Extremely | 65 (13.40%) | ||

| Physical and mental experiences during COVID-19 | Being diagnosed with COVID-19 | 40 (8.25%) | |

| Fear of getting COVID-19 | 135 (27.84%) | ||

| Fear of giving COVID-19 to someone else | 185 (38.14%) | ||

| Worrying about friends, family, partners, etc. | 236 (48.66%) | ||

| Stigma or discrimination from other people | 23 (4.74%) | ||

| Personal financial loss | 41 (8.45%) | ||

| Frustration or boredom | 160 (32.99%) | ||

| Not having enough basic supplies | 24 (4.95%) | ||

| More anxiety | 151 (31.13%) | ||

| More depression | 70 (14.43%) | ||

| More sleep, less sleep, or other changes to your normal sleep pattern | 115 (23.71%) | ||

| Increased alcohol or other substance use | 79 (16.29%) | ||

| A change in sexual activity | 43 (8.87%) | ||

| Loneliness | 106 (21.86%) | ||

| Confusion about what COVID-19 is, how to prevent it, or why social distancing/isolation/quarantines are needed | 24 (4.95%) | ||

| Feeling that I was contributing to the greater good by preventing myself or others from getting COVID-19 | 167 (34.43%) | ||

| Getting emotional or social support from family, friends, partners, a counsellor, or someone else | 89 (18.35%) | ||

| Getting financial support from family, friends, partners, an organisation, or someone else | 10 (2.06%) | ||

| Other difficulties or challenges | 49 (10.10%) | ||

| General Self Efficacy Scale (GSE) | |||

| Average self efficacy score | 3.04 / 4 (0.46) | ||

| Burnout Assessment Tool-12 (BAT-12) | |||

| Exhaustion score | 8.57 / 15 (2.75) | Cognitive impairment score | 8.05 / 15 (2.51) |

| Mental distance score | 7.33 / 15 (2.86) | Emotional impairment score | 5.46 / 15 (2.42) |

| The Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) | |||

| Average discrimination score | 0.77 / 5 (0.65) | ||

3.5. Geographical

3.6. Qualitative

3.6.1. Work-Life Balance

3.6.2. Information Technology (IT) and Remote/Hybrid Working

3.6.3. Changes to the Workplace

3.6.4. Communication

3.6.5. Administration

3.6.6. Staff Redeployment, Recruitment, and Shortages

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. Available online: WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.. (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Coronavirus Legislation. Available online: Coronavirus Legislation. (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Mitchell, E.J.; Ahmed, K.; Breeman, S.; Cotton, S.; Constable, L.; Ferry, G.; Goodman, K.; Hickey, H.; Meakin, G.; Mironov, K.; Quann, N. It is unprecedented: trial management during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Trials 2020, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, A. Clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges of putting scientific and ethical principles into practice. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2020, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Trial Jobs in United Kingdom. Available online: Clinical Trial Jobs in United Kingdom - 2022 | Indeed.com. (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Urgent public health COVID-19 studies. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/covid-studies/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Thornton, J. Clinical trials suspended in UK to prioritise covid-19 studies and free up staff. BMJ 2020, 368, m1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitencourt, M.R.; Alarcão, A.C.; Silva, L.L.; Dutra, A.D.; Caruzzo, N.M.; Roszkowski, I.; Bitencourt, M.R.; Marques, V.D.; Pelloso, S.M.; Carvalho, M.D. Predictors of violence against health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesuthasan, J.; Powell, R.A.; Burmester, V.; Nicholls, D. ‘We weren’t checked in on, nobody spoke to us’: an exploratory qualitative analysis of two focus groups on the concerns of ethnic minority NHS staff during COVID-19. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, C.W.; Pang, E.P.; Lam, L.C.; Chiu, H.F. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; Tan, H. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiri, P.; Delanerolle, G.; Al-Sudani, A.; Rathod, S. COVID-19 and black, Asian, and minority ethnic communities: a complex relationship without just cause. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e22581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiri, P.; Rathod, S.; Elliot, K.; Delanerolle, G. The Impact of COVID-19 on the mental wellbeing of healthcare staff. EJPMR 2020, 7, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Delanerolle, G.; Rathod, S.; Elliot, K.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Thayanandan, T.; Sandle, N.; Haque, N.; Raymont, V.; Phiri, P. Rapid commentary: Ethical implications for clinical trialists and patients associated with COVID-19 research. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom to Speak Up Review. Available online: http://freedomtospeakup.org.uk/the-report/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Khorasanee, R.; Grundy, T.; Isted, A.; Breeze, R. The effects of COVID-19 on sickness of medical staff across departments: A single centre experience. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, S.; Pallikadavath, S.; Young, A.H.; Graves, L.; Rahman, M.M.; Brooks, A.; Soomro, M.; Rathod, P.; Phiri, P. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic: Protocol and results of first three weeks from an international cross-section survey-focus on health professionals. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2020, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers’ mental health. Jaapa 2020, 33, 45–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: a scoping review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Questionnaire | Cut-off scores | Construct | Analytic Rationale | Dimensions |

| Demographic information | None | Equity issues | Moderator | One dimension |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | A total score of 11 or higher indicates the probable presence of the mood disorders, with a score of 8 to 10 being just suggestive of the presence of the respective state. | Psychological impact - Anxiety & Depression | Outcome measure |

Anxiety score (odd items) Depression score (even items) |

|

General Self-Efficacy (GSE) |

None |

Assessment of general self-efficacy |

Moderator | One dimension |

|

Pandemic Stress Index (PSI) |

None | Psychological impact | Outcome measure | One dimension |

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) |

A score of: 0-7 is indicative of no insomnia; 8-14 indicative of a subthreshold insomnia; 15-21 moderate insomnia; 22-28 is indicative of severe insomnia. |

Psychological impact - Sleep Quality | Outcome measure | One dimension |

|

Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA) |

None | Disadvantages and equity issues - cultural context | Moderator or mediator |

Heritage score Mainstream score |

| Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT-12) | None | Psychological impact | Moderator |

Exhaustion score Mental distance score Cognitive impairment score Emotional score impairment |

|

The Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) |

None | Workplace and occupational | Moderator or mediator | One dimension |

| AHRQ Patient safety culture survey | None | Workforce and occupational | Moderator or mediator | One dimension |

| Demographics - Questionnaire respondents (N = 485) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N(%) | Variables | N(%) | ||

| Age |

18 - 24 11 (2.3%) 25 - 34 90 (18.6%) 35 - 44 131 (27.0%) 45 - 54 115 (23.7%) 55 - 64 70 (14.4%) 65 and over 21 (4.3%) Not available 47 (9.7%) |

Religion | Christian 135 (27.8%) Muslim 9 (1.9%) Hindu 1 (0.2%) Jewish 1 (0.2%) Buddhist 2 (0.4%) Sikh 2 (0.4%) No religion 268 (55.3%) Other 13 (2.7%) Not available 54 (11.1%) |

||

| Gender | Female 356 (73.4%) Male 75 (15.5%) Other 2 (0.4%) Prefer not to say 5 (1.0%) Not available 47 (9.7%) |

Ethnicity | African 1 (0.2%) Asian 8 (1.6%) Bangladesh 2 (0.4%) Black 2 (0.4%) Indian 5 (1.0%) Pakistani 4 (0.8%) White & Asian 3 (0.6%) White & Black African 3 (0.6%) White & Caribbean 2 (0.4%) White British 340 (70.1%) White Irish 3 (0.6%) Other background 34 (7.0%) Prefer not to say 6 (0.6%) Not available 72 (14.8%) |

||

| Nationality | United Kingdom 265 (54.6%) Not available 220 (45.4%) |

||||

| Healthcare professional |

Yes 60 (12.4%) No 379 (78.1%) Not available 46 (9.5%) |

||||

| Job title |

Administration / Management 193 (39.8%) Attending / Staff physician 2 (0.4%) Physician assistant / Nurse practitioner 3 (0.6%) Registered nurse 25 (5.1%) Unit assistant / Clerk / Secretory 5 (1.0%) Other 208 (42.9%) Not available 49 (10.1%) |

Professional group (Healthcare professional = Yes N = 60) |

Academic research 5 (8.3%) Allied Health Professional 4 (6.7%) Allied Health Professional by training 4 (6.7%) Clinical Trialist 5 (8.3%) Doctor 4 (6.7%) Nurse 31 (51.7) Other 6 (10.0%) |

||

| Health and wellbeing | |||||

|

Suffer from any long-term conditions |

Yes 125 (25.8%) No 277 (57.1%) Prefer not to say 7 (1.4%) Not available 76 (15.7%) |

Suffer from any disabilities |

Yes 19 (3.9%) No 384 (79.1%) Prefer not to say 3 (0.6%) Not available 79 (16.3%) |

||

|

Taking medication for any mental health condition |

Yes 65 (13.4%) No 337 (69.5%) Prefer not to say 6 (1.2%) Not available 77 (15.9%) |

Taking medication for any physical condition | Yes 103 (21.2%) No 297 (61.2%) Prefer not to say 5 (1.0%) Not available 80 (16.5%) |

||

|

Mental health rating since the pandemic began |

Much better 15 (3.1%) Somewhat better 38 (7.8%) About the same 137 (28.2%) Somewhat worse 173 (35.7%) Much worse 36 (7.4%) Not available 86 (17.7%) |

Physical health rating since the pandemic began |

Much better 19 (3.9%) Somewhat better 46 (9.5%) About the same 176 (36.3%) Somewhat worse 141 (29.1%) Much worse 18 (3.7%) Not available 85 (17.5%) |

||

|

Test positive for COVID-19 in the past 12 months |

Yes 51 (10.5%) No 350 (72.2%) Not available 84 (17.3%) |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).