Submitted:

28 February 2023

Posted:

02 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

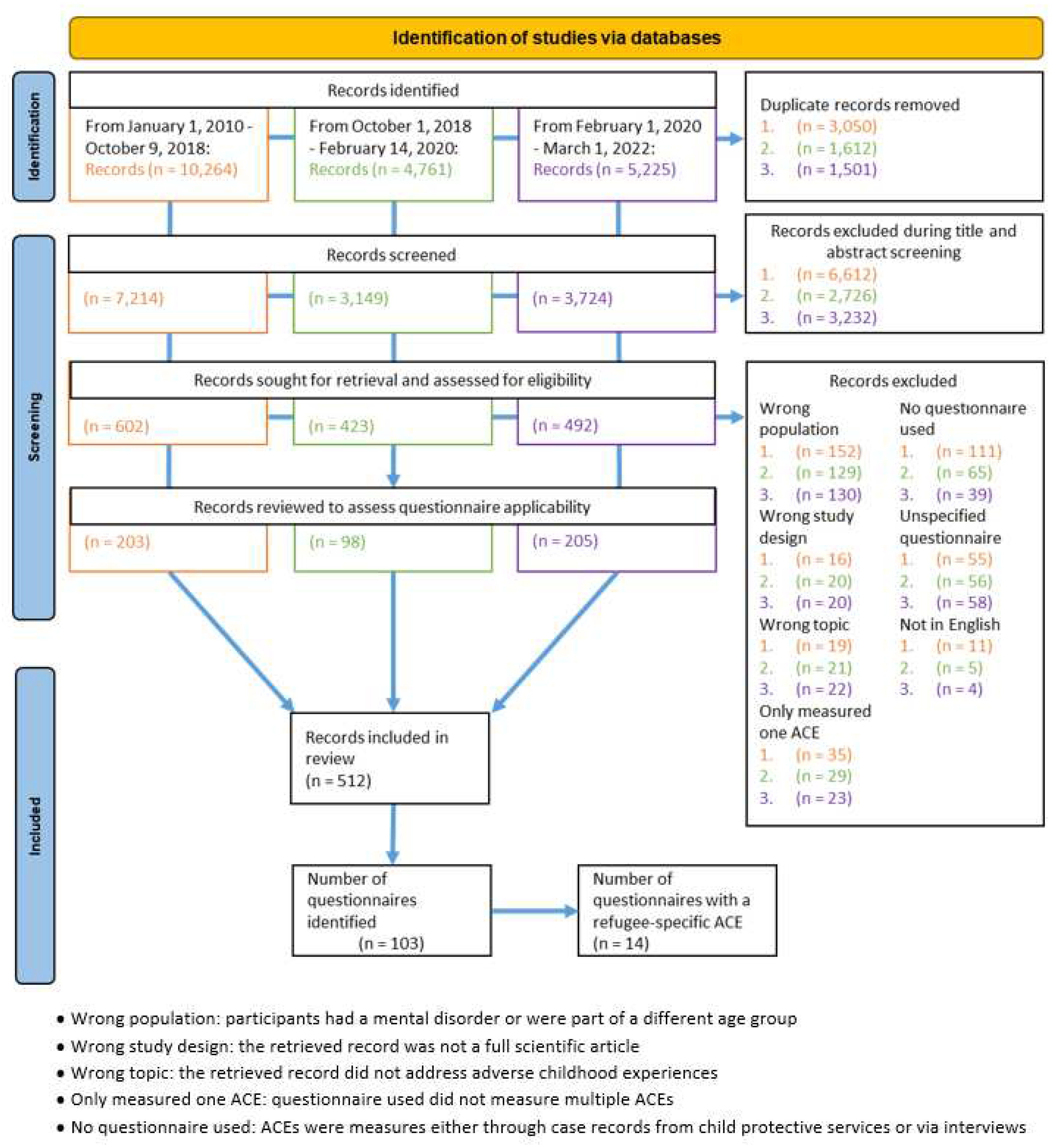

Search strategy

Screening

Data extraction and item assessment

Analytic Strategy

Results

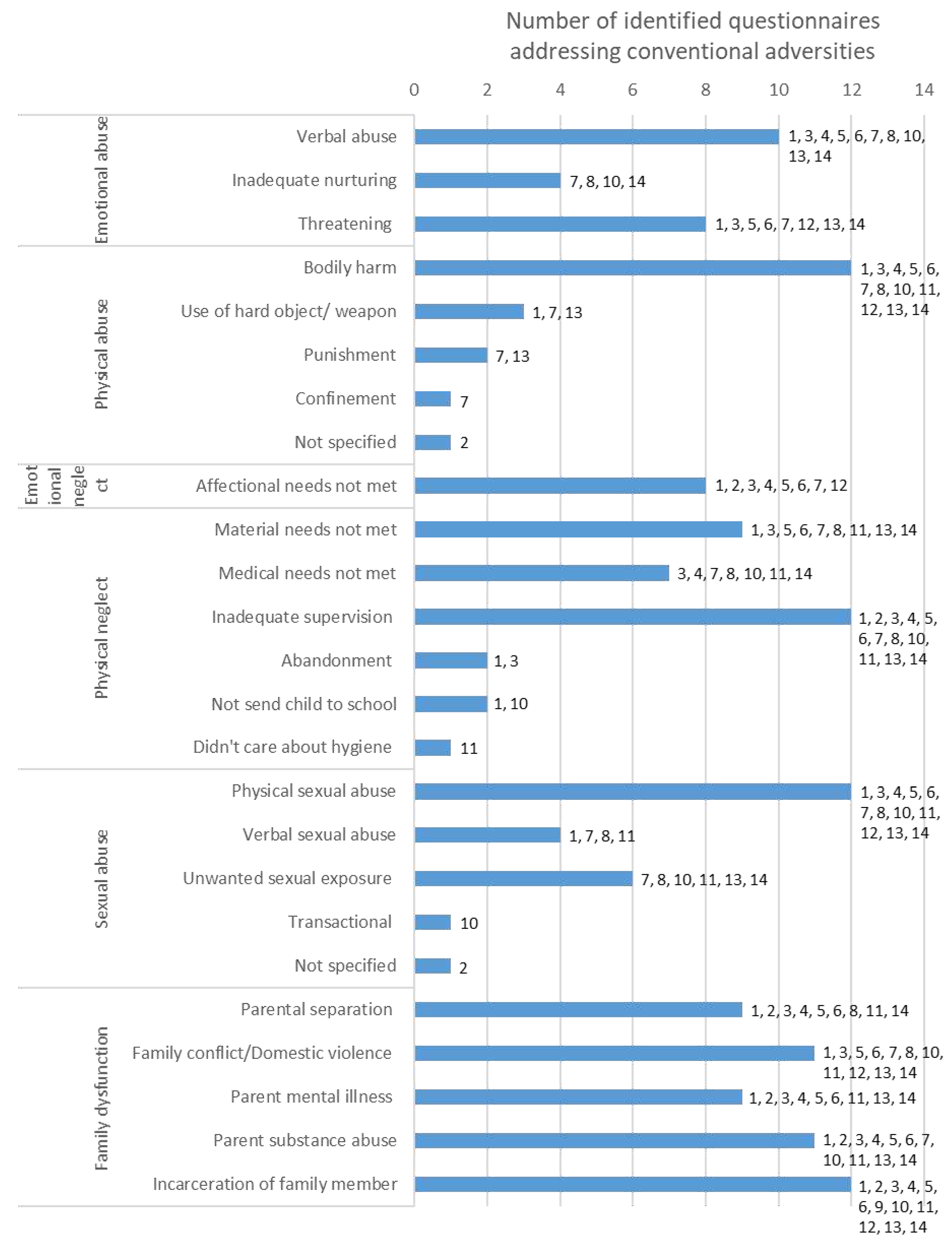

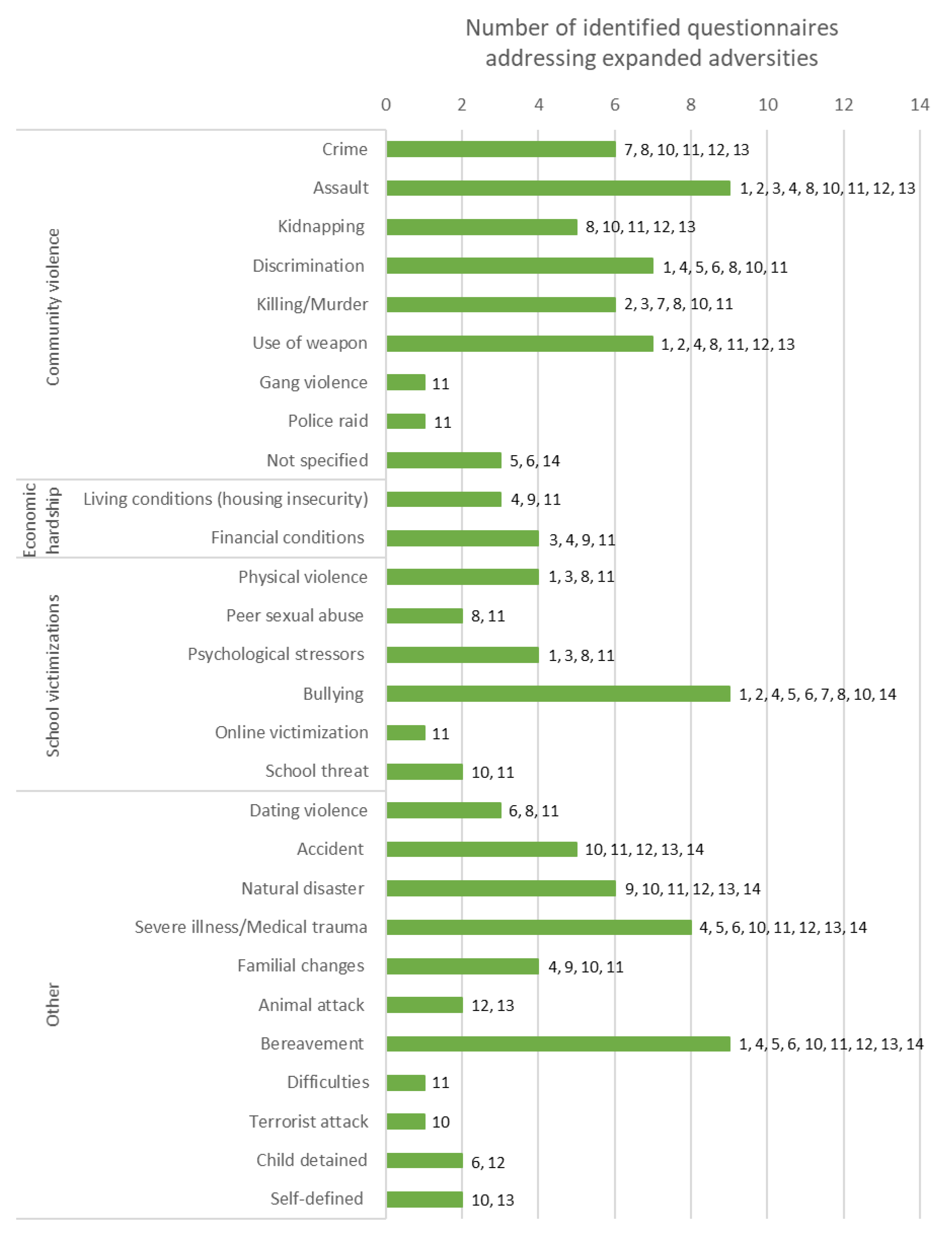

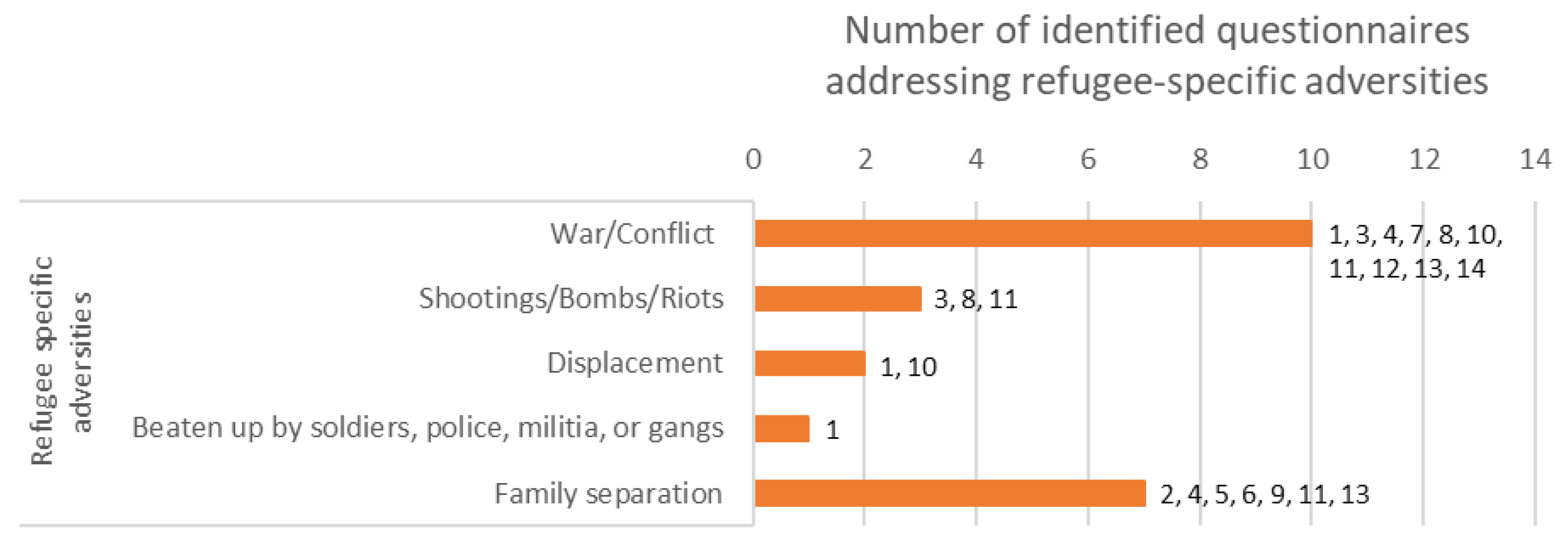

Adversities measured

| Figures 2a-c | |

|

|

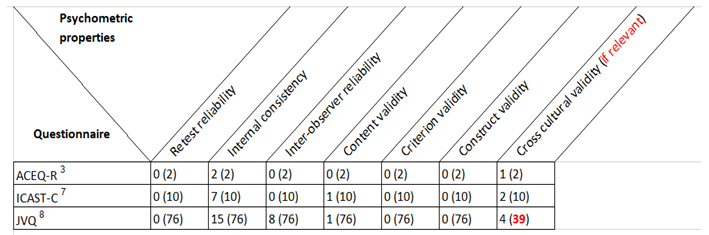

Psychometrics and questionnaire quality

|

|

Questionnaires used within a refugee population

Discussion

Adversities measured

Questionnaire Quality

Questionnaires used within a refugee setting

Limitations and strengths

Conclusion

References

- Adebowale, V., et al., Addressing Adversity, in Prioritising adversity and trauma-informed care for children and young people in England, M. Bush, Editor. 2018, The YoungMinds Trust: Great Britain. p. 372.

- Felitti, V.J., et al., Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1998. 14(4): p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Zeanah, P.; Burstein, K.; Cartier, J. Addressing adverse childhood experiences: It’s all about relationships. Societies 2018, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, S. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics, 2016. 137(3): p. e20154079. [CrossRef]

- Kia-Keating, M.; et al. Trauma-responsive care in a pediatric setting: Feasibility and acceptability of screening for adverse childhood experiences. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, M.J., M.J. Sulik, and A.F. Lieberman, Traumatic Life Events and Psychopathology in a High Risk, Ethnically Diverse Sample of Young Children: A Person-Centered Approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 2016. 44(5): p. 833-844. [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, S.T., et al., Adverse childhood experiences and children's development in early care and education programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2021. 72: p. 101218. [CrossRef]

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American journal of preventive medicine 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.; Ruiz, M.O.; Rovnaghi, C.R.; Tam, G.K.; Hiscox, J.; Gotlib, I.H.; Barr, D.A.; Carrion, V.G.; Anand, K.J. The social ecology of childhood and early life adversity. Pediatric research 2021, 89, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, W.R. and W.H. Dietz, A New Framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood and Community Experiences: The Building Community Resilience Model. Academic Pediatrics, 2017. 17(7, Supplement): p. S86-S93. [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; et al. Methods to Assess Adverse Childhood Experiences of Children and Families: Toward Approaches to Promote Child Well-being in Policy and Practice. Academic Pediatrics, 2017. 17(7, Supplement): p. S51-S69. [CrossRef]

- Karam, E.G.; Fayyad, J.A.; Farhat, C.; Pluess, M.; Haddad, Y.C.; Tabet, C.C.; Farah, L.; Kessler, R.C. Role of childhood adversities and environmental sensitivity in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in war-exposed Syrian refugee children and adolescents. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 214, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. Refugee facts: What is a Refugee? 2021 30.06.2022]. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/what-is-a-refugee/.

- UNHCR. Refugee Data Finder. Key Indicators 2022 16.06.2022 25.06.2022]. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

- UNICEF. Two million refugee children flee war in Ukraine in search of safety across borders. 2022 30.03.2022 24.10.2002]. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/two-million-refugee-children-flee-war-ukraine-search-safety-across-borders.

- Nations, U. Peace and Conflict Resolution. 07.09.2022]. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/peace-and-conflict-resolution.

- NCTSN. About Refugees 24.08.2022]. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/refugee-trauma/about-refugees.

- Vaghri, Z.; Tessier, Z.; Whalen, C. Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Children: Interrupted Child Development and Unfulfilled Child Rights. Children (Basel) 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Miconi, D.; Farrar, J.; Brooks, M.A.; Rousseau, C.; Betancourt, T.S. Mental Health of Refugee Children and Youth: Epidemiology, Interventions, and Future Directions. Annual Review of Public Health 2020, 41, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turney, K. Cumulative adverse childhood experiences and children’s health. Children and Youth Services Review 2020, 119, 105538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Rienks, S.; McCrae, J.S.; Watamura, S.E. The co-occurrence of adverse childhood experiences among children investigated for child maltreatment: A latent class analysis. Child abuse & neglect 2019, 87, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, D.; Puljak, L. Language restrictions in systematic reviews should not be imposed in the search strategy but in the eligibility criteria if necessary. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2021, 132, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembly, U.N.G. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989 [cited 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text#.

- Choi, B.C.; Pak, A.W. Peer reviewed: a catalog of biases in questionnaires. Preventing chronic disease 2005, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Community Violence. 24.08.2022]. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/community-violence.

- Leventhal, T. and J. Brooks-Gunn, Poverty and Child Development, in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes, Editors. 2001, Pergamon: Oxford. p. 11889-11894.

- Braveman, P.; Heck, K.; Egerter, S.; Rinki, C.; Marchi, K.; Curtis, M. Economic Hardship in Childhood: A Neglected Issue in ACE Studies? Maternal and child health journal 2018, 22, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrov, J.M. and K.J. Perry, Bullying and Peer Victimization in Early Childhood, in Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development (Second Edition), J.B. Benson, Editor. 2020, Elsevier: Oxford. p. 228-235.

- Ray, D.C.; Angus, E.; Robinson, H.; Kram, K.; Tucker, S.; Haas, S.; McClintock, D. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences, social-emotional competencies, and problem behaviors among elementary-aged children. Journal of child and adolescent counseling 2020, 6, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, S., et al., Voices of the displaced: A qualitative study of potentially traumatising and protective experiences faced by refugee children. medRxiv, 2022: p. 2022.07.26.22277918. [CrossRef]

- Laurin, J.; Wallace, C.; Draca, J.; Aterman, S.; Tonmyr, L. Youth self-report of child maltreatment in representative surveys: a systematic review. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada : research, policy and practice 2018, 38, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.C.d.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Guirardello, E.d.B.; Souza, A.C.d.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Guirardello, E.d.B. Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity [Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade]. Epidemiology and Health Services [Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde] 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D. and H. Turner. National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence III, 1997-2014 [United States] (ICPSR 36523). 2016 [cited 2022 17/10/2022]. Available online: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/studies/36523.

- WHO. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). 2020 28.01.2020 28.10.2022]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/adverse-childhood-experiences-international-questionnaire-(ace-iq).

- Selvaraj, K.; Ruiz, M.J.; Aschkenasy, J.; Chang, J.D.; Heard, A.; Minier, M.; Osta, A.D.; Pavelack, M.; Samelson, M.; Schwartz, A. , et al. Screening for Toxic Stress Risk Factors at Well-Child Visits: The Addressing Social Key Questions for Health Study. The Journal of pediatrics 2019, 205, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. A revised inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 2015, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koita, K.; Long, D.; Hessler, D.; Benson, M.; Daley, K.; Bucci, M.; Thakur, N.; Burke Harris, N. Development and implementation of a pediatric adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other determinants of health questionnaire in the pediatric medical home: A pilot study. PloS one 2018, 13, e0208088–e0208088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellness, C.f.Y. ACE-Q Materials. 2015 26.10.2022]. Available online: https://centerforyouthwellness.org/aceq-pdf/.

- ISPCAN. ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tools (ICAST). 2020 25.08.2022]. Available online: https://www.ispcan.org/learn/icast-abuse-screening-tools/?v=402f03a963ba.

- Finkelhor, D.; Hamby, S.L.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H. The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire: reliability, validity, and national norms. Child abuse & neglect 2005, 29, 383–412. [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, M.T.; Henly, M.; Turner, H.A.; David-Ferdon, C.; Hamby, S.; Kacha-Ochana, A.; Simon, T.R.; Finkelhor, D. Beyond residential mobility: A broader conceptualization of instability and its impact on victimization risk among children. Child abuse & neglect 2018, 79, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynoos, R.S. and A.M. Steinberg, UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 (e-mail from Alan to first author). 2021. p. 28.

- Ford, J., et al., Traumatic events screening inventory for children (TESI-C) Version 8.4. National Center for PTSD and Dartmouth Child Psychiatry Research Group, 2002.

- Ghosh-Ippen, C., et al., Trauma events screening inventory-parent report revised. San Francisco: The Child Trauma Research Project of the Early Trauma Network and The National Center for PTSD Dartmouth Child Trauma Research Group, 2002.

- Hudziak, J. and J. Kaufman. Yale-Vermont Adversity in Childhood Scale (Y-VACS): Adult, Child, Parent, & Clinician Questionnaires. 2014. Available online: https://www.kennedykrieger.org/sites/default/files/library/documents/faculty/Y-VACS_Child_Self-Report_4.2020.pdf.

- Meyer, S.; Yu, G.; Hermosilla, S.; Stark, L. Latent class analysis of violence against adolescents and psychosocial outcomes in refugee settings in Uganda and Rwanda. Global Mental Health 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsha, N.; Lynch, M.A.; Giacaman, R. Child abuse in the West Bank of the occupied Palestinian territory (WB/oPt): social and political determinants. BMC public health 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, M.; Reed, R.V.; Panter-Brick, C.; Stein, A. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012, 379, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehnel, R.; Dalky, H.; Sudarsan, S.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Resilience and mental health among Syrian refugee children in Jordan. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2022, 24, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharpf, F.; Kaltenbach, E.; Nickerson, A.; Hecker, T. A systematic review of socio-ecological factors contributing to risk and protection of the mental health of refugee children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review 2021, 83, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangrio, E.; Zdravkovic, S.; Carlson, E. A qualitative study of refugee families’ experiences of the escape and travel from Syria to Sweden. BMC Research Notes 2018, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cFarlane, C.A.; Kaplan, I.; Lawrence, J.A. Psychosocial Indicators of Wellbeing for Resettled Refugee Children and Youth: Conceptual and Developmental Directions. Child Indicators Research 2011, 4, 647–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.; Fazel, M.; Bowes, L.; Gardner, F. Pathways linking war and displacement to parenting and child adjustment: A qualitative study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Social Science & Medicine 2018, 200, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.; Haslam, N. Predisplacement and Postdisplacement Factors Associated With Mental Health of Refugees and Internally Displaced PersonsA Meta-analysis. JAMA 2005, 294, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, L.S.; Melvin, G.A.; Newman, L.K. An exploration of the adaptation and development after persecution and trauma (ADAPT) model with resettled refugee adolescents in Australia: A qualitative study. Transcultural Psychiatry 2016, 53, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleijpen, M.; Mooren, T.; Kleber, R.J.; Boeije, H.R. Lives on hold: A qualitative study of young refugees’ resilience strategies. Childhood 2017, 24, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- urtis, P.; Thompson, J.; Fairbrother, H. Migrant children within Europe: a systematic review of children's perspectives on their health experiences. Public Health 2018, 158, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, K.; Hipfner-Boucher, K.; Yamashita, A.; Riehl, C.M.; Ramdan, M.A.; Chen, X. Acculturation through the lens of language: Syrian refugees in Canada and Germany. Applied Psycholinguistics 2020, 41, 1351–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, T.; Georgiades, K.; Khanlou, N.; Wahoush, O. Understanding Mental Health and Identity from Syrian Refugee Adolescents’ Perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2021, 19, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [37].

- Culbertson, S. and L. Constant, Education of Syrian Refugee Children: Managing the crisis in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. 2015: RAND Corporation.

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [36, 37, 40, 42-44].

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [35, 38, 39, 41, 45].

- Wood, S.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences in child refugee and asylum seeking populations. 2020.

- Henley, J.; Robinson, J. Mental health issues among refugee children and adolescents. Clinical Psychologist 2011, 15, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwi, K. Refugee children and their health, development and well-being over the first year of settlement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2017. 53(9): p. 841-849. [CrossRef]

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [36, 39, 40].

- Jiang, H.; Hu, H.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, H. Effects of school-based and community-based protection services on victimization incidence among left-behind children in China. Children & Youth Services Review 2019, 101, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; You, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, R.; Liu, X.; Leung, F. A longitudinal study testing the role of psychache in the association between emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2019, 75, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Graff, L.E.; Scheid, C.R.; Guzmán, D.B.; Grein, K. Caregiver and family factors promoting child resilience in at-risk families living in Lima, Peru. Child Abuse & Neglect 2020, 108, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.L.; Artz, L.; Leoschut, L.; Kassanjee, R.; Burton, P. Sexual violence against children in South Africa: a nationally representative cross-sectional study of prevalence and correlates. The Lancet. Global health 2018, 6, e460–e468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjersing, L.; Caplehorn, J.R.; Clausen, T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC medical research methodology 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Aunio, P.; Hakkarainen, A. A systematic review evaluating psychometric properties of parent or caregiver report instruments on child maltreatment: Part 1: Content validity. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2021, 22, 1013–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Aunio, P.; Hakkarainen, A. A systematic review evaluating psychometric properties of parent or caregiver report instruments on child maltreatment: Part 2: Internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, and criterion validity. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2021, 22, 1296–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Relations’s, C.o.F. Global Conflict Tracker. 07.09.2022]. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker.

- Fazel, M.; Stein, A. The mental health of refugee children. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2002, 87, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ACE Category | Forms of adversities |

|---|---|

| Conventional ACEs | |

| Emotional abuse |

A child's family member: • Verbal abuse: swore, insulted or put them down • Threatening: behaved in a way that made the child fearful they would be physically harmed • Inadequate nurturing: says things such as not wanting the child or wished the child were dead • Torment: afflicts mental suffering by hurting the child’s pet, withholding a meal, or singling out the child to do chores |

| Physical abuse | A child’s family member: • Bodily harm: pushed, grabbed, slapped, etc. the child • Use or hard object/weapon: hit child with a belt, cord, etc. or cut child with sharp object • Punishment: harsh treatment as a retribution for an offence such as wash mouth with soap or pepper, child dug, slashed a field, or other labour as punishment • Confinement: tied the child up, gagged the child, blindfolded them, or locked them in a closet or a dark place |

| Emotional neglect |

|

| Physical neglect |

The failure, refusal or inability on the part of a caregiver, for reasons other than poverty, to provide for their child’s • Material needs: child sometimes went without food, clothing, shelter or protection • Medical needs: child not taken to the doctor when sick • Supervisory needs: parents do not ensure a safe place for child to stay, child left at home alone, or child is left in charge of younger siblings for long periods of time |

| Sexual abuse |

• Physical sexual abuse: someone attempted to have sexual intercourse with the child, touched the child’s private parts, or asked child to touch their private parts in a sexual way that was unwanted, uncomfortable or against child’s will • Verbal sexual abuse: someone said/wrote something sexual about the child, talked to child in a sexual way or made sexual comments about child’s body • Unwanted sexual exposure: someone attempted or made child watch sexual things (e.g. magazines, pictures, videos, internet sites), made child look at their private parts or wanted child to look at theirs, took sexual picture/video of child, or child was present when someone was being forced to engage in sexual activity • Threatening: someone threaten to have sex with child, or hurt/tell lies about them unless they did something sexual • Transactional: child traded sex or sexual activity to receive money, food, drugs, alcohol, a place to stay, or anything else. |

| Family dysfunction | • Parental separation or divorce: child’s parents are divorced or separated • Domestic violence: child witnessed a parent hit, slap, kick, push or physically hurt another parent or siblings, child has seen or heard family members arguing very loudly or threaten to seriously harm each other • Mental illness: a family member was depressed, mentally ill, or (attempted) suicide • Substance abuse: a family member is a problem drinker/alcoholic or uses street drugs • Incarceration: a family member served time in jail or was or taken away (by police, soldiers, or other authorities) |

| Community violence |

Interpersonal violence committed in public areas by individuals who are not intimately related to the child. Examples include • Crime: robbery, theft, vandalism, exposure to drug activity • Assault: child witnessed or was exposed to being attacked with/without an object or weapon • Kidnaping: child was kidnaped • Discrimination: child was hit or attacked verbally because of skin colour, religion, family origin, physical condition, or sexual orientation • Killing: hear about/witness to murder • Use of a weapon: hearing about/witness to random shootings/stabbings |

| Economic hardship | Child’s family facing financial hardship: • Financial instability: income loss, unemployment, job instability, not being able to afford food and necessities • Housing insecurity: child was living in a car, a homeless shelter, a battered women’s shelter, or on the street |

| School victimisations |

• Physical violence: another child and/or teacher physically hit, kicked, pushed, taken things forcibly from the child • Psychological stressors: another child and/or teacher emotionally mistreats a child by social exclusion, threatening relationship termination, gossip and secret spreading • Sexual offence: another child or teen pressures the child to so sexual things or did something sexual to child against their wishes • Bullying: child threatened or harassed by a bully • Online victimisations: cyber bullying or online sexual harassment |

| Other |

• Dating violence: being hit, verbally hurt or controlled by partner • Accident: experience/witness a serious car/bicycle accident, near drowning experience or fire • Natural disaster: child experiences a disaster such as a tornado, hurricane, big earthquake, flood or mudslide • Severe illness/Medical trauma: child or loved one had to undergo frightening medical treatment or was hospitalized for a long time period • Animal attack: child badly hurt by an animal • Bereavement: death of someone close to the child • Familial changes: child completely separated from parent/caregiver for a long time under very stressful circumstances, such as going to a foster home, the parent living far apart from him/her, or never seeing the parent again. Addition of third adult to family (e.g. marriage of parent to step-parent) • Child detained: child was detained, arrested or incarcerated • Difficulties: move to a new school, home, or town, repeat a grade in school, etc. |

| Refugee-specific adversities |

• War/conflict: child is exposed to war or conflict • Shootings, bombs and riots: child could see or hear people being shot, bombs going off, or street riots • Displacement: child is forced to flee their home • Beaten up by soldiers, police, militia, or gangs: child is hurt badly by armed adults • Family separation: child is separated from their caregiver due to immigration or war |

| Name of Questionnaire | Adversity categories | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | Physical abuse | Emotional neglect | Physical neglect | Sexual abuse | Family dysfunction | Community Violence | Economic Hardship | School victimizations | Other | Refugee-specific adversity | |

| ACE-International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) [34] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Addressing Social Key (ASK) Questions for Health Questionnaire [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire-Revised (ACEQ-R) [36] | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 2 | |

| BARC Pediatric Adversity and Trauma Questionnaire [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Center for Youth Wellness ACE-Questionnaire (CYW ACE-Q Child) [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Center for Youth Wellness ACE-Questionnaire (CYW ACE-Q Teen) [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool (ICAST-C) [39] | 7 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ) [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Lifetime Destabilizing Factor (LDF) Index [41] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Modified UCLA Trauma History Profile [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | ||

| National Surveys of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) [33] | 1 | 5 | 7 | 18 | 21 | 2 | 17 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for Children (TESI-C) [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | |||

| Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for Children (TESI-PRR) [44] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 2 | |||

| Yale-Vermont Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (Y-VACS) [45] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||

| (Values indicate the number of questions addressing each adversity category in the questionnaire) | |||||||||||

| Stage of migration | ||||

| Refugee relevant ACES | Pre-flight | Flight | Post-flight | |

| War/Conflict 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10-14 | ||||

| Shootings/bombs & riots 3, 8, 11 | ||||

| Destruction of infrastructure | ||||

| Presence of militant groups | ||||

| Displacement1, 10 | ||||

| Deprivation of basic necessities 3, 9, 11 | ||||

| Beaten up by police/soldiers/militia etc. 1 | ||||

| Witnessing/Experiencing violence 1-8, 10-14 | ||||

| Kidnapping 8, 10-13 | ||||

| Extortion/exploitation/fraud | ||||

| Housing insecurity 4, 9, 11 | ||||

| Arrest of the child 6, 12 | ||||

| Assault 1- 4, 8, 10-13 | ||||

| Family dysfunction 1-14 | ||||

| Emotional and physical abuse and neglect 1, 3-7 | ||||

| Sexual abuse 1-8, 10-14 | ||||

| Parent missing | ||||

| Bereavement 1, 4-6, 10-14 | ||||

| Crime/Theft 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13 | ||||

| Economic hardship (unemployment, financial difficulties) 3, 9, 11 | ||||

| Bullying 1-8, 10, 11, 14 | ||||

| Interruption of education | ||||

| Separation from family 2, 4-6, 9, 11, 13 | ||||

| Discrimination 1, 4-6, 8, 10, 11 | ||||

| Immigration detention | ||||

| Immigration process | ||||

| Acculturation stress | ||||

| Refugee specific adversity forms identified within this review are accentuated in bold | ||||

|

|

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).