1. Introduction

Spatial transcriptomics encompasses a recent series of methods that aim to provide molecular maps of the RNA transcriptome of single cells within its natural tissue context [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Whereas some methods use patterned substrates to capture RNA sequences [

6] or fluidics to barcode spatial information within the tissue [

7], while others consist of light microscopy-based techniques/approaches to visualize the transcripts directly [

8,

9,

10]. A key aspect for all these light-microscopy-based methods is the need to reliably and uniquely identify each individual transcript. In this regard, a common challenge arises when the observed field of view (FOV) becomes saturated with fluorescent targets. This effect, also known as optical crowding, diminishes the ability to effectively visualize and quantitatively identify individual transcripts. Observing a small set of genes becomes technically challenging when the expression level of a few of them or even a single one is relatively high.

Several approaches address this problem in different ways. First, most methods use different wavelengths to partition the set of genes into smaller groups (commonly three or four ‘colors’), which can be then visualized within a single imaging session, e.g. [

11]. Methods such as MERFISH [

9,

12] or seqFISH+ [

10] additionally rely on highly sparse encoding where the individual transcript generates a signal in a few of several performed imaging cycles. While this allows for the identification of a larger set of genes, it also requires for a likewise large number of cycles. seqFISH+ requires, for example, 80 cycles [

10], thereby prolonging the acquisition times and increasing the potential risk of photobleaching. A further problem with performing a large number of cycles is that tissue integrity may degrade over time. Moreover, technical problems related to these relatively complex protocols, such as bubble formation in fluidics or tissue detachment may result in unsuccessful experiments. On the other hand,

in situ sequencing (ISS) methods do not rely on sparsity and instead encode the complete set of genes of interest in a combinatorial manner, which arises by the product of the number of unique wavelengths available and total number of imaging cycles performed [

13]. However, this approach is limited to up to about 200 genes, considering the use of four different color channels and performing at least four to six cycles. Beyond wavelengths, another limiting factor in ISS arises from expression level; gene targets are required to have a low- to mid-expression level so that optical crowding is not a major problem.

The physical size of the individual transcripts to be visualized and the resolution of the imaging system used contribute both as well to the aforementioned difficulties. Whereas MERFISH or seqFISH+ generate diffraction-limited spots, those generated by ISS are about 1 µm in diameter [

8]. This is because, unlike single-molecule methods, ISS involves an amplification step which increases both the size of the spots and the number of fluorescent labelling sites. To achieve this, barcoded padlock probes (PLPs) recognize and bind genetic targets

in situ and amplify them by rolling circle amplification (RCA), forming long single-stranded DNA repeats known as rolling circle products (RCPs) [

8]. This procedure makes it possible to visualize the genetic targets even with standard epifluorescence microscopy and low magnification objectives [

8,

13], in contrast to MERFISH or seqFISH+ which rely heavily on high-numerical aperture (NA), high-magnification objectives. While lower magnification objectives allow the acquisition of larger areas of tissue at a faster rate, resolution is also sacrificed.

In this work we explore the effect of structured-illumination microscopy (SIM) in combination with both low- and high-magnification objectives on the localization of individual fluorescent amplicon spots. We hypothesized that an improvement in both contrast and resolution provided by SIM would enhance spot-localization performance in ISS experiments, while maintaining relatively large FOVs. Overall, we found that SIM increases both spot detection accuracy and efficiency in comparison to diffraction-limited widefield (with or without deconvolution post-processing) and confocal images. The observed improvement is consistent with low-NA 20, mid-NA 25X and high-NA 60X objectives, respectively. Altogether, the results presented suggest that SIM delivers more flexibility in the choice of the imaging modality and magnification level, which allows the study of samples and genes of diverse density and complexity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All experimental subjects were adult male C57BL/6 mice obtained from local EMBL or EMMA colonies or from Charles River Laboratories (Calco, Italy).

2.2. Histology

Mice were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PB. Brains were left to postfix overnight in 4% PFA at 4 °C. Brains were either sectioned in PBS with a vibratome (Leica VT1000s) or cryo-sectioned. For cryo-sectioning brains were first briefly rinsed in PBS after post-fixation, then left in 30% sucrose in PBS for 2 days before flash freezing in pre-chilled isopentane. Frozen brains were sectioned on a cryostat (Leica CM3050s). Coronal sections of 5 µm were taken from areas of interest.

2.3. In situ sequencing

ISS experiments were performed either with CARTANA (Now 10x Genomics) kits or following the HybISS protocol [

13,

14] using individual components. For the kits, samples were processed following manufacturer instructions. Several neuronal panels from CARTANA were used, in particular the general CNS, the inhibitory and excitatory and glia panels.

2.4. Imaging

Imaging was carried out using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon) equipped with CrestOptics X-Light V3 spinning disk system and the DeepSIM X-Light super-resolution add-on module (CrestOptics), Celesta multi-mode multi-line laser source (Lumencor) and Kinetix sCMOS camera (Photometrics). The whole imaging set-up was controlled by NIS-Elements Microscope Imaging software (Nikon). Images were acquired in various channels, according to the experiment, using laser excitations at 405, 477, 546, 638 and 749 nm. Appropriate filters for DAPI, GFP, Cy3, Cy5 and Cy7 were used. Stack images were acquired with 0.8 NA CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda D 20X air objective (Nikon), 1.05 NA CFI Plan Apo Lambda S 25X silicone oil objective (Nikon) and 1.42 NA CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda D 60X oil objective (Nikon) with z-step of 1 µm, 0.5 µm and 0.3 µm respectively. Widefield, spinning disk confocal and DeepSIM super-resolution acquisitions were performed on 1024x1024 pixels tile size to cover the same sample area with the three imaging modalities. SIM super-resolution raw images were reconstructed with 25 iterations of the CrestOptics DeepSIM reconstruction algorithm through the NIS Element software.

2.5. Deconvolution

Deconvolution was done using DeconWolf [

15]. Point spread functions were generated for each wavelength and the numerical aperture of the objective used within DeconWolf following software instructions. 20 iterations and a tile size of 2048 pixels were used. After deconvolution a maximum projection was generated using the same package.

2.6. Data analysis

Gene transcript spot detection was performed using the RS-FISH [

16] plugin for ImageJ. For all datasets, the optimal parameters were first determined over a subset of images using the interactive mode, with an anisotropy coefficient of 1 and the RANSAC method for spot fitting. Once determined, these parameters (provided in

Appendix A,

Table A1) were introduced as a macro in ImageJ for automatic processing of all images. For every case, the spot intensity threshold was set to 0 and no background subtraction was performed. Once generated, detected spot localizations and intensities were saved as CSV files. Graphs were built using custom code in RStudio.

3. Results

3.1. Structured-illumination microscopy enhances contrast and improves resolution of amplified individual transcripts

First, we carried out hybridisation-based

in situ sequencing (HybISS) [

13] on a mouse brain coronal section, targeting 4 highly expressed genes (

Actb,

Gapdh,

Atp1a3 and

Slc17a7). Only two channels were used for visualization of all four genes in order to increase the density of distinguishable spots per channel (

Figure 1). For simplicity we refer to the grouped pair of genes as either

gene x and

gene y. First, we visualized the sample using widefield (

Figure 1, left panels) as a standard method of reference and then using SIM for the same FOVs (

Figure 1, right panels). In both cases, a 25X silicon oil immersion plan-apochromatic objective with a NA of 1.05 was used. This objective was used mainly because it combines both relatively high NA and FOV (~7.09x104 µm

2), especially when compared to 20X objectives commonly used for these applications [

13]. Detailed examination of the obtained images revealed that diffraction-limited spots imaged in widefield mode contain significant blur and poor contrast, and are not clearly resolved as individual objects (

Figure 1, left panels). Using SIM to image the same amplicons yielded individual spots with enhanced contrast and resolution (

Figure 1, right panels).

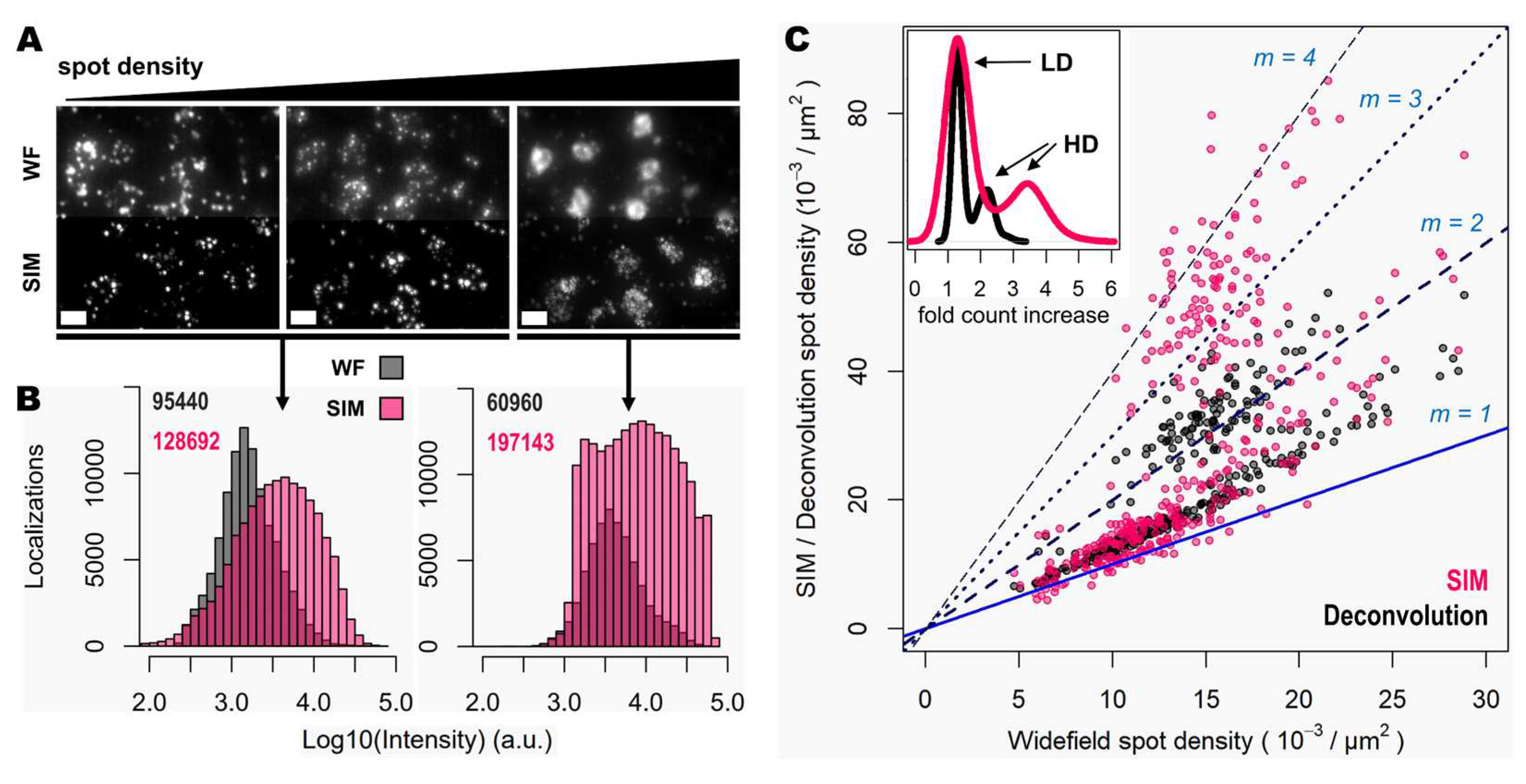

Next, the improvement in image quality provided by SIM was compared to the one achieved when applying deconvolution to widefield images, as it has been shown to improve spot detection during image processing of ISS experiments [

15]. Although deconvolution on widefield acquisitions increases image contrast by means of a deblurring effect (

Figure 1, middle panels), the improvement in resolution is limited compared to that achievable using SIM. Furthermore, a thorough examination of the same FOVs acquired with SIM or with widefield shows that: (i), SIM is able to detect a larger number of bright spots compared to widefield (

Figure 2A); (ii), most of those bright spots in SIM acquisitions were spots that had lower intensity in the widefield image (

Figure 2A); and (iii), SIM rescues those spots with low intensity signals that were poorly visible in widefield or, even worse, confused with the background (

Figure 2A).

To quantify the potential improvements in spot detection using SIM instead of widefield, images corresponding to thirty different positions of the mouse brain slice were processed using RS-FISH [

16]. Quantification of spots and their relative intensity (

Figure 2B) revealed similar trends to those that can be observed from visual inspection of the images: a higher fraction of bright and dim spots is identified with SIM as a result of contrast increase achieved with such structured illumination technique. Worth noting is also that a slight decrease of the highest intensity of spots in SIM acquisitions compared to the widefield ones (black bars in the right extreme of

Figure 2B), as most likely brightest spots may have been decomposed into multiple spots due to the resolving ability of SIM over signals in close proximity. Overall, the use of SIM increases the number of detected spots about 40% (13756 vs. 9740 per mm

2 for SIM and widefield respectively,

Figure 2B).

Since the resolution improvement provided by SIM may be even more beneficial in areas of higher spot density, we also quantified the number of detected spots with SIM or deconvolution against those detected in widefield for specific FOVs with increasing transcript density (

Figure 2C). The use of deconvolution as a pre-processing step in the image analysis pipeline, as demonstrated previously [

15], improves spot detection (grey dots in

Figure 2C) by about 30%. In contrast, the use of SIM shows for some FOVs even twice as many spots (represented as those measurements which lie in close proximity to the line with a slope m = 2, in

Figure 2C), compared to those detected using widefield (pink dots in

Figure 2C). It was expected only to see an incremental effect of SIM with higher spot densities, however, even at relatively low densities the use of SIM increased the number of detected transcripts. The average optical density of imaged transcripts with HybISS was 15349 ± 3226, 26750 ± 4780 and 36059 ± 6357 (mean +/- SEM) spots/mm

2 for widefield, deconvolution and SIM images, respectively and for the same FOVs (

Figure 2C). These results indicate that the use of SIM in combination with a 25X silicon oil immersion plan-apochromatic objective provides an increase of up to two-fold in spot detections of amplified single mRNA transcripts.

3.2. Spot detection performance is enhanced for relatively low- and highly-expressed genes with moderate magnification and NA

As the main effect of SIM is more pronounced for higher densities (

Figure 2C), we sought to test even denser areas. Therefore, we carried out HybRISS [

17], which targets directly the mRNA molecule of the gene of interest instead of its cDNA (HybISS) and, as a consequence, produces more spots per gene [

17]. To further increase the observed density, we used a 200 gene panel encoded in six imaging cycles, so that for any given cycle, there are about 50 genes per channel visualized. For this experiment, we decided to use a 20X objective with 0.8 NA since it is the most commonly used for such experimental design. Here, again we imaged the same FOVs using widefield and SIM consecutively (

Figure 3A). Similar to what we observed for the 25X, the use of SIM improved contrast, reduced background and increased resolution (

Figure 3B). Upon detailed observation we noticed that each channel had a particular optical density of spots (

Figure 3C). For simplicity, we refer to the grouped genes as

gene x,

gene y and

gene z for the Cy3, Cy5 and Cy7 channels respectively.

Detailed examination of the 20X images in widefield mode revealed blurry and unresolved spots, which became easier to identify as single entities when imaged by SIM (

Figure 3B). As done for the data with the 25X, we used RS-FISH to retrieve the location of single spots and extract their intensity. We examined in detail the spots detected using the widefield images and compared them against those detected using SIM or deconvolution post-processing of the widefield images. It was observed that, similar to the experiment with the 25X, deconvolved images yield more detections than those in widefield mode. However, SIM provides the highest improvement, with a more noticeable effect as spot density increases (

Figure 3C, right panels). We chose detection parameters to extract the majority (if not all) of the fluorescent objects that could be seen for a variety of images without introducing artefacts or picking up false positives from background noise (see Methods). Briefly, these parameters (provided in

Appendix A) determine the average radius of true spots that were localized, an intensity threshold to discriminate between the fluorescent objects and the background, and algebraical constraints which filter out low-quality detections based on radial symmetry and decrease spot localization error. Since it would be impractical to determine the best set of values for each image within any dataset separately, a small random subset of images was chosen and detection parameters were adjusted so that these behaved robustly and accurately for all the selected examples. Once fine-tuned, those parameters were applied to the whole dataset for automatic processing. Based on our data, the use of SIM improves both the resolution and the overall the quality of the imaged fluorescent objects, which renders more accurate and reliable spot detection (

Figure 3C).

While some gene transcripts are distributed more evenly within the cell cytoplasm (yellow and red spots in

Figure 3A,B), others localize preferentially to specific regions in tissue or are even confined to subcellular structures such as the nucleus, as dense clusters (magenta spots in

Figure 3A,B). We were interested in assessing the performance of spot detection in mid-to-low density areas as well as within those clusters (

Figure 4A). Therefore, we kept the quantification of spots number and their relative intensity separated between images of spots at lower densities from those at higher density forming clusters (

Figure 4A,B). The average number of detected spots per unit area (10

-3/μm

2) were 13 ± 1, 16 ± 1 and 17 ± 1 (mean ± SEM, N=30) for the lower density genes whereas the numbers were 16 ± 1, 34 ± 3 and 52 ± 5 (mean ± SEM, N=30) for the more densely clustered spots, in widefield, deconvolution and SIM modes, respectively (

Figure 4B). Detailed examination of the spot detection as a function of density showed that using SIM allows recovery of larger numbers compared to widefield (

Figure 4C). However, at low-to-medium densities the use of SIM shows no significant difference over the use of deconvolution (

Figure 4C) at low magnification (in this case, 20X). Spot detection from SIM images recovered almost four times as many spots from the high density and clustered areas compared to widefield (

Figure 4B,C), and about twice as much compared to widefield plus deconvolution (

Figure 4C). The use of SIM, when imaging with a conventional 20X 0.8 NA, significantly benefits spot detection at high densities and/or clusters of amplified single RNA transcripts.

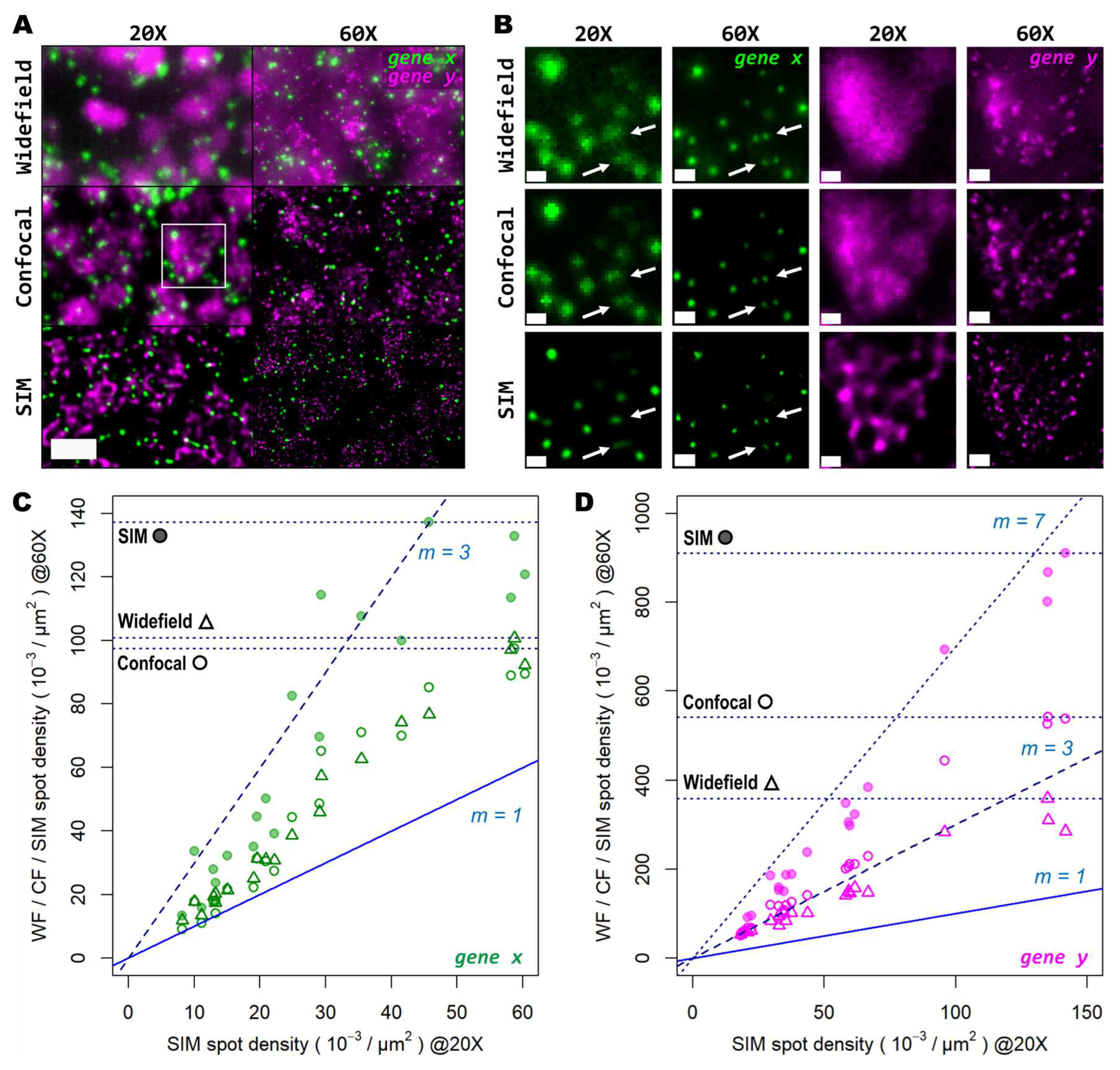

3.3. High magnification, high NA and super-resolution is needed for precise transcript localisation in crowded regions

Next, we tested whether examination of the sample at higher magnification would allow for the discovery of more genetic targets within the tissue. Again, we investigated two genes with notable differences in number of transcripts per unit area. For this comparison, both a conventional 20X 0.8 NA air objective and a 60X 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective were used. Several FOVs of the mouse brain tissue processed with the same HybRISS protocol were imaged at 20X and 60X in widefield, spinning disk confocal and SIM modes, consecutively (

Figure 5A and Supp.

Figure S1A-H). Here, we analyzed the set of genes encoded in the filters for Cy5 and Cy7 channels (for the grouped

gene x and

gene y, respectively). Detailed examination revealed that: (i) most

gene x spots at low density are recognized as single entities even with the low-magnification 20X objective and correspond to those observed at high NA 60X objective, except for a small fraction of

gene x spots that are not distinguishable with the low NA 20X objective (

gene x in

Figure 5A,B, white arrows); (ii) the crowded

gene y spots are completely unresolved into a uniform single blob when imaged with the 20X objective in widefield and confocal modes, and they are resolved as individual objects only either with the use of SIM or the high NA 60X objective (

gene y in

Figure 5B). To provide another point of comparison, we also imaged of the same FOV with spinning disk confocal microscopy (

Figure 5A,B, middle panels). As expected, confocality provided an improvement in contrast and out-of-focus light rejection compared to widefield, however, with a smaller effect than that provided by SIM. When super-resolution was performed in combination with the 60X objective, many individual spots within these highly crowded areas were then visible (

Figure 5B, lower-right panel,

gene y in magenta). While super-resolution provides an evident improvement in spot detection performance in low magnification, higher light collection efficiency (i.e. NA) is indispensable for very crowded regions even in SIM mode.

In

Figure 5C,D we show the ratio between the number of localized spots in low magnification SIM mode in comparison to high magnification widefield, spinning disk confocal and SIM modes, for both the low- and high-density genes. In this case, a similar trend as from the previous experiments performed with the 20X and 25X objectives alone, was observed (

Figure 5C,D): confocality and SIM increased amplicon localization detection efficiency with a more notable effect for more densely distributed transcripts (Supp.

Figure S1I-J). At very low densities (i.e. 1-2 spots per 100 μm

2), the use of high NA and high magnification, regardless of the imaging modality, has little advantage over the lower NA 20X objective, as the number of localizations (depicted as filled/empty circles and triangles, one for each FOV analyzed) remain in close proximity to the identity slope (

Figure 5C, m=1). Beyond this narrow regime, starting at 3 spots per 100 μm

2 the use of higher NA results in a notable higher number of localizations compared to SIM with the 20X. Widefield and confocal provide both about twice as much localizations while SIM imaging provides about three times more compared to the 20X images. For denser areas, the effects of higher NA were even more pronounced (

Figure 5D). Widefield provided an improvement in the number of localizations of about 2.7 times (

Figure 5D, triangles), while the confocal raised that to about 3.5 times (

Figure 5D, empty circles). SIM at 60X imaging with high NA, had the largest effect with up to 7 times more localizations compared to its 20X counterpart (

Figure 5D, filled circles). The commonly used 20X seems to be a poor choice for spatial transcriptomics experiments as it misses the detection of individual transcripts at all except for very low densities. For any medium- to high densities higher NA than 0.8 are needed to reliably detect spots.

4. Discussion

In general, super-resolution provided by the SIM module delivers a good performance to accurately and reliably detect targeted transcripts in spatial transcriptomics experiments. The performance of SIM is better than that of widefield or confocal imaging methods with or without deconvolution image post-processing. The commonly used 20X 0.8 NA objective in combination with super-resolution and even spinning disk confocal imaging provides sufficient detail for the identification of, for example, low expression genes. However, this effect is considerably inferior in comparison to that provided by higher NA objectives. In this regard, the 25X (or 30X) 1.05 NA objective represents a viable alternative to account for the needed resolution while maintaining relatively large FOVs and reliable image acquisition times. Moreover, other commercially available options such as the 40X objective series with NA ranging from 1.25 (silicon oil immersion), to 1.3 and 1.4 (oil immersion) could also provide the ideal resolution needed by imaging-based spatial transcriptomics applications.

For ISS multiplex experiments, transcript identification depends on the correct localization of single fluorescent spots, whose position must remain constant throughout all the imaging cycles. In this sense, the increased localization precision delivered by SIM is of great benefit for signal decoding and identification of individual transcripts. In this work, the average amplicon size was observed to be ~300 nm (data not shown), which suggests that relatively higher densities could be reliably examined in contrast to the previously reported amplicon size [

8,

18]. In particular, several hundreds of reads per cell could be achieved with the size reported in this work, based on the estimated maximum number of reads for an ISS experiment [

8]. Higher densities can arise by looking at a large number of genes or by looking at certain genes with very high expression levels. SIM has, therefore, the potential capacity to improve the dynamic range of gene expression measurement of ISS experiments.

Here, we performed ISS experiments in thin 5 μm tissue sections. Most current commercial instruments offer solutions for thin slices only. In the near future, the field of spatial biology will move towards transcriptomic profiling of thicker samples and up to whole organs and embryos. These thicker samples will require optical sectioning capacity for volumetric acquisitions. For these needs, spinning disk confocal or light sheet microscopy may be the modality of choice rather than widefield to better reduce the blurring effect of out-of-focus light along the Z-axis. Although SIM could provide the desired optical sectioning, it may be challenging to image large sample volumes at reasonable times. Nonetheless, SIM can help to untangle high density areas and resolve numerous spots in close proximity in selected regions. Having the possibility to easily switch between different modalities, from SIM to confocal or from light sheet to SIM, might be helpful to address the large variety of samples to be profiled. Recent advances in structured-illumination microscopy within light sheet systems [

19] or confocal microscopy [

20] could hold the key to allow visualization of whole transcriptomes within entire organs and embryos.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AL, FB, CB and AHC; methodology, SE, CB and AHC; formal analysis, AL; investigation, AL and AHC; resources, CB, FB, and AHC; writing—original draft preparation, AL and AHC; visualization, AL; supervision, AHC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EMBL.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study as mice did not undergo any experimental procedure and were obtained as unwanted production from a different project.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Histology, Microscopy and Laboratory of Animal Resources facilities of EMBL Rome. We thank Daniele Ancora and Alessandra Scarpellini for their feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

FB and CB are employees of Crest Optics, a company that produces the structured-illumination module used in this study. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. AL, SE and AHC declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The spot localization parameters used within the RS-FISH plugin in Fiji are specified below.

Table A1.

Spot detection parameters for the RS-FISH plugin.

Table A1.

Spot detection parameters for the RS-FISH plugin.

| |

20X (Figure 3 & 4) |

25X (Figure 1 & 2) |

| |

Sigma |

Thres. |

S.R.R. |

Inlier R. |

Max E. |

Sigma |

Thres. |

S.R.R. |

Inlier R. |

Max E. |

| WF |

1.75 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.9 |

1.25 |

2.5 |

0.0015 |

2.5 |

0.75 |

1.25 |

| DEC |

2.25 |

0.0015 |

2 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

2.5 |

0.0015 |

2.5 |

0.75 |

1.25 |

| SIM |

1.5 |

0.0015 |

2 |

0.5 |

1.25 |

2 |

0.0015 |

2 |

0.9 |

1 |

| |

20X (Figure 5 & S1) |

25X (Figure 5 & S1) |

| |

Sigma |

Thres. |

S.R.R. |

Inlier R. |

Max E. |

Sigma |

Thres. |

S.R.R. |

Inlier R. |

Max E. |

| WF |

1.5 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.85 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.85 |

1.25 |

| CF |

1.5 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.85 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.85 |

1.25 |

| SIM |

2 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

2 |

0.002 |

2 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

References

- Asp, M.; Bergenstrahle, J.; Lundeberg, J. , Spatially Resolved Transcriptomes-Next Generation Tools for Tissue Exploration. Bioessays 2020, 42, e1900221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, V. , Method of the Year: spatially resolved transcriptomics. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Barkley, D.; Franca, G. S.; Yanai, I. , Exploring tissue architecture using spatial transcriptomics. Nature 2021, 596, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, L.; Pachter, L. , Museum of spatial transcriptomics. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.G.; Lee, H.J.; Asatsuma, T.; Vento-Tormo, R.; Haque, A. , An introduction to spatial transcriptomics for biomedical research. Genome Med 2022, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriques, S.G.; Stickels, R.R.; Goeva, A.; Martin, C.A.; Murray, E.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Welch, J.; Chen, L.M.; Chen, F.; Macosko, E.Z. , Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science 2019, 363, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Deng, Y.; Su, G.; Enninful, A.; Guo, C.C.; Tebaldi, T.; Zhang, D.; Kim, D.; Bai, Z.; Norris, E.; Pan, A.; Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Halene, S.; Fan, R. High-Spatial-Resolution Multi-Omics Sequencing via Deterministic Barcoding in Tissue. Cell 2020, 183, 1665–1681 e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, R.; Mignardi, M.; Pacureanu, A.; Svedlund, J.; Botling, J.; Wahlby, C.; Nilsson, M. , In situ sequencing for RNA analysis in preserved tissue and cells. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 857–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.H.; Boettiger, A.N.; Moffitt, J.R.; Wang, S.; Zhuang, X. , RNA imaging. Spatially resolved, highly multiplexed RNA profiling in single cells. Science 2015, 348, aaa6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, C.L.; Lawson, M.; Zhu, Q.; Dries, R.; Koulena, N.; Takei, Y.; Yun, J.; Cronin, C.; Karp, C.; Yuan, G.C.; Cai, L. , Transcriptome-scale super-resolved imaging in tissues by RNA seqFISH. Nature 2019, 568, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, J.Y.; Lapan, S.W.; Beliveau, B.J.; West, E.R.; Zhu, A.; Sasaki, H.M.; Saka, S.K.; Wang, Y.; Cepko, C.L.; Yin, P. , SABER amplifies FISH: enhanced multiplexed imaging of RNA and DNA in cells and tissues. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Su, J.H.; Beliveau, B.J.; Bintu, B.; Moffitt, J.R.; Wu, C.T.; Zhuang, X. , Spatial organization of chromatin domains and compartments in single chromosomes. Science 2016, 353, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyllborg, D.; Langseth, C.M.; Qian, X.; Choi, E.; Salas, S.M.; Hilscher, M.M.; Lein, E.S.; Nilsson, M. , Hybridization-based in situ sequencing (HybISS) for spatially resolved transcriptomics in human and mouse brain tissue. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilscher, M.M.; Gyllborg, D.; Yokota, C.; Nilsson, M. , In Situ Sequencing: A High-Throughput, Multi-Targeted Gene Expression Profiling Technique for Cell Typing in Tissue Sections. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2148, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erik Wernersson, E.G., Gabriele Girelli, Su Wang, David Castillo, Christoffer Mattsson Langseth, Huy Nguyen, Shyamtanu Chattoraj, Anna Martinez Casals, Emma Lundberg, Mats Nilsson, Marc Marti-Renom, Chao-ting Wu, Nicola Crosetto, Magda Bienko, Deconwolf enables high-performance deconvolution of widefield fluorescence microscopy images. 2022. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Bahry, E.; Breimann, L.; Zouinkhi, M.; Epstein, L.; Kolyvanov, K.; Mamrak, N.; King, B.; Long, X.; Harrington, K. I. S.; Lionnet, T.; Preibisch, S. RS-FISH: precise, interactive, fast, and scalable FISH spot detection. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 1563–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Marco Salas, S.; Gyllborg, D.; Nilsson, M. , Direct RNA targeted in situ sequencing for transcriptomic profiling in tissue. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sountoulidis, A.; Liontos, A.; Nguyen, H.P.; Firsova, A.B.; Fysikopoulos, A.; Qian, X.; Seeger, W.; Sundstrom, E.; Nilsson, M.; Samakovlis, C. , SCRINSHOT enables spatial mapping of cell states in tissue sections with single-cell resolution. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Chang, B.J.; Roudot, P.; Zhou, F.; Sapoznik, E.; Marlar-Pavey, M.; Hayes, J.B.; Brown, P.T.; Zeng, C.W.; Lambert, T.; Friedman, J.R.; Zhang, C.L.; Burnette, D.T.; Shepherd, D.P.; Dean, K.M.; Fiolka, R.P. , Resolution doubling in light-sheet microscopy via oblique plane structured illumination. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Han, X.; Su, Y.; Glidewell, M.; Daniels, J.S.; Liu, J.; Sengupta, T.; Rey-Suarez, I.; Fischer, R.; Patel, A.; Combs, C.; Sun, J.; Wu, X.; Christensen, R.; Smith, C.; Bao, L.; Sun, Y.; Duncan, L.H.; Chen, J.; Pommier, Y.; Shi, Y.B.; Murphy, E.; Roy, S.; Upadhyaya, A.; Colon-Ramos, D.; La Riviere, P.; Shroff, H. Multiview confocal super-resolution microscopy. Nature 2021, 600, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).